BIRDING TOURS WORLDWIDE

Welcome to Birding Ecotours! Here we will present to you some of the world’s most spectacular birding tours around the world. Our trips are for small groups of only 6-8 participants. Quality is of paramount importance to us; we prefer to use superior accommodation (where available at the top birding sites) and vehicles. Despite our focus on small groups and the fact that we err on the side of superior quality, our prices are competitive. It is Birding Ecotours’ company policy to contribute a minimum of 10 % of profits to conservation and local communities. We are passionate about birding and also about leaving a legacy – by genuinely helping people and conserving birds – for generations to come.

We like to do things differently. For example, we offer some unique tours in addition to our standard birdwatching tours, including Owls of the World® tours , tough mammal tours (fancy an Aardvark or a Black-footed Cat?), and more. Since 2003, we have been innovating some of the most wonderful bird and wildlife tours available.

What is one of our typical birding tours like?

Our main focus is, of course, on finding the important birds (especially the endemics and specials). Our trip lists are very important to us (we do really encourage you to look at our trip reports – which contain bird and mammal lists – and compare them with those of other companies). However, we understand that birding tours can be tiring, so we as a company prefer to add a day or two and actually have folks enjoy the birding tour – this allows us to accumulate a big bird list (including backup time for finding the most important birds), but it also gives us time to enjoy the bird sightings, as well as to stop for each species of mammal (plus other interesting things we may encounter along the way) rather than to be forced to tell our guests “sorry, we have no time to stop for anything without feathers” – that can be frustrating. Hence, we tend to add a couple of days so we can get the best bird lists in the industry, but without as much of a huge rush as some other companies’ bird tours. As just one example, we must have the most comprehensive eastern South Africa birding tour out there (by the way, so many mammals are also seen on this trip, incidentally to the birding).

We also run a good number of Birding Photo Tours , which need a different approach from typical birding tours – more space in the vehicles for camera gear, the correct tour pace to get photos, making sure the vehicle is at the right angle, and constantly thinking about lighting (although these things are important even on a standard birding tour, they are even more vital on a photographic birding/wildlife vacation). We also operate various other kinds of tours such as birding and wildlife cruise holidays , pelagic trips and 1-day birding tours . Our main focus, of course, is on birding tours !

One of the things we pride ourselves in the most, though, is our enthusiasm which means we get back to you with excitement from the minute you contact us. We tend to struggle to contain our enthusiasm and excitement, so when you e-mail us, you’ll doubtless find that we get back to you fast with detailed information. It’s our contagious enthusiasm for birding (and for the natural world as a whole) and for people, that spurs us on to give outstanding service.

RECENT BLOGS

Getting to know Joshua Olszewski

Field Guides to the Neotropics: what to take into the field

Book Review: Yellowstone’s Birds

Bird Book Review: Birds of Greater Southern Africa

Recent trip reports.

Birding Southern and Central Vietnam: Endemics and Specials Set Departure Trip Report, March 2024

Birding Tour Japan: Spectacular Winter Birds Custom Tour Trip Report, February 2024

USA: Minnesota: Set Departure Birding Trip Report, January 2024

Highland Zimbabwe To Coastal Mozambique Set Departure Birding Trip Report, November 2023

Monthly video.

WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT US

Dylan Vasapolli is extremely knowledgeable about birding and photography, but it’s his enthusiasm for the subject that is wonderful to experience. He has been birding for many years, and still, he has such a love for birding and the environment, which is very infectious. I was extremely lucky to have him as my guide.

We just returned from our trip to Thailand. It was wonderful. Thank you very much for arranging our tour with Andy Walker. He was the best guide we ever had. He is knowledgeable,easy going, hard working, and has all the qualities that people expect from a guide. We really enjoyed birding with him. We would be happy to go birding with him any time and would highly recommend him as a guide to any of our friends. Thanks again for giving us the opportunity to have him as our guide.

What do you most need in a guide and a tour company? Some would say trustworthy arrangements that yet stay flexible to the needs of the individual birder, some would say someone who can find you the target birds and others might say an all-rounder who combines birding knowledge, great communications skills and organisational ability. Birding Ecotours and its owner/operator Chris Lotz tick all the boxes! I’ve birded with Chris and travelled with the company and asked them to arrange tours for others, and Chris has come up trumps every time. I value my own integrity too much to give endorsements unless I have personal experience that truly warrants it. I recommend Chris Lotz and Birding Ecotours!

Our birding trip to Ethiopia was fantastic. The country is so rich in history and interesting people and customs. The birding was great! Needless to say Dominic is an expert birder. He is a warm and gracious person and we all really enjoyed his company. Our Ethiopian driver and guide, Tesfaw, was also very good. He was an experienced guide and driver. His contacts were good as were his day to day decisions. He kept our group on time and on schedule but was also flexible to our requests and needs. We rate our trip excellent (A,10/10). Thank you for all your work in arranging the trip. We appreciate all your prompt correspondences. We certainly will be using Birding Ecotours in the future. We hope to meet you in person some day.

I’ve just returned from our custom tour with Eduardo and I want to tell you – he is a jewel! Very knowledgeable, approachable, friendly and seems to enjoy birding and helping other birders find and appreciate the birds. His guiding, listening and decorum were beyond reproach. He could many times describe where the target bird was, rather than just pointing and scaring it away. A true gentleman and very helpful when I needed help or clarification. It would be a pleasure to go again with him. He was able to find 26 lifers for me when I expected at the most 19. Now my world list total is 7466 and counting!

Maine is beautiful, whether you’re on the shore or inland, and this tour showed us the best of both. Experiencing the variety of habitats with a knowledgeable guide and great companions was just what we needed after a year of not travelling. Jacob was a great leader for our group, making sure we saw the birds we wanted, but also on the look-out for mammals or letting us slow down to enjoy the wildflowers.

I would definitely recommend Birding Ecotours! Before the trip, we had prompt responses to our enquiries and we were fast assigned to a guide, Dominic Rollinson. We had such a great time with Dom on our day out in the Cape Peninsula. He was flexible with the schedule, itinerary, and with our photographic demands. He adjusted the trip so that we did everything at a slower pace, to be able to take pictures of literally every bird we saw. He knew how to position the car to get a better light on the subject, when that was the case. He’s very patient and pleasant to be with, and he shared with us some tips on where to go during the next days.

Andy Walker is a truly exceptional guide. His ready knowledge of both the local and worldwide birds is phenomenal. Andy is a very kind, helpful guide who repeatedly went out of his way to help all of us on the tour. I would bird again with him and, in fact, that's just what I'm doing right now, as I'm in Manokwari, W. Papua for the start of another tour with him. Andy has my highest recommendation.

Andy Walker is one of the best, good-natured birding guides who has served me on 42 guided tours. He makes certain that everyone in the group has seen each bird and keeps at it until that happens. The two Indonesian tours I took with Andy immediately before this one was excellent and I was able to meet my goals of seeing the last three bird families of all 248 (eBird/Clements list) and to see half of all bird species. Andy has my highest recommendation to other birders – he will serve you well!

GET OUR NEWSLETTER

All Rights Reserved, Birding Ecotours

Join our newsletter for exclusive discounts and great birding information!

Eagle-Eye Tours offers exceptional Birding and Wildlife Tours worldwide

Small groups.

We believe small-groups are essential for a quality, enjoyable travel experience. Our tours have a guide-to-client ratio that reflects a more intimate travel experience.

Expert Guides

Our guides are expert birders and naturalists and go the extra mile to ensure an optimal experience during your trip.

We Give Back

We believe it’s important to give back to help conserve the birds and other wildlife that we so enjoy. Read more about what we do.

Birding Tours Worldwide

Small ship expedition cruises and sailing adventures, where do you want to go.

- Canada & USA

- Mexico, Central America & Caribbean

- South America

- Asia & Australasia

Most Popular Tours

Patagonia Wildlife Safari

Panama: Canal Zone & the Darien

Arizona in Winter

What our customers are saying.

Read More Reviews

eagleeyetours

We have been offering high quality birding tours and expedition cruises with exceptional leaders worldwide for 25+ years!

- Conservation

- In the media

- Birding blog

- How to book

- Booking FAQs

- Plan your trip

- Land Tour FAQs

- Insurance FAQ

WHERE WE GO

- Mexico & Central America

- Australia & New Zealand

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

2 Hours Guided Birdwatching in Moscow

- Moscow, Russia We will discuss a meeting point individually accoding to tha park of interest that we choose.

- We will discuss pickup details individually

- Not wheelchair accessible

- Service animals allowed

- Near public transportation

- Confirmation will be received at time of booking

- Most travelers can participate

- This experience requires good weather. If it’s canceled due to poor weather, you’ll be offered a different date or a full refund

- This experience requires a minimum number of travelers. If it’s canceled because the minimum isn’t met, you’ll be offered a different date/experience or a full refund

- This tour/activity will have a maximum of 10 travelers

- For a full refund, cancel at least 24 hours in advance of the start date of the experience.

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as wait time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

2 Hours Guided Birdwatching in Moscow provided by Birdwatching Moscow

- Ascension Island

- Tristan da Cunha

- Burkina Faso

- Central African Republic

- Congo Republic

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eswatini (Swaziland)

- Guinea Bissau

- North Sudan

- São Tomé & Príncipe

- Sierra Leone

- Eastern Cape

- KwaZulu Natal

- Northern Cape

- Northwest Province

- Western Cape

- South Sudan

- Western Sahara

- Afghanistan

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Heilongjiang

- Inner Mongolia

- Andaman & Nicobar Islands

- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Chhattisgarh

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Lakshadweep

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttarakhand

- West Bengal

- Indonesian Borneo

- Lesser Sundas

- Kuala Lumpur

- Peninsular Malaysia

- Sarawak & Sabah

- North Korea

- Philippines

- South Korea

- Timor-Leste

- Turkmenistan

- American Samoa

- Christmas Island

- Coral Sea Islands

- New South Wales

- Norfolk Island

- Northern Territory

- South Australia

- Western Australia

- Cocos Islands

- Cook Islands

- French Polynesia

- Marshall Islands

- New Caledonia

- Stewart Island

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Papua New Guinea

- Wallis & Futuna

- Netherlands Antilles

- Antigua & Barbuda

- Caribbean Netherlands

- Cayman Islands

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Puerto Rico

- Saint Lucia

- St Vincent & Grenadines

- St. Kitts & Nevis

- Turks & Caicos

- South Ossetia

- Republic of Croatia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

- Bourgogne-Franche-Comté

- Hauts-de-France

- Île-de-France

- Nouvelle-Aquitaine

- Pays-de-la-Loire

- Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur

- Baden-Württemberg

- Brandenburg

- Lower Saxony

- Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

- North Rhine-Westphalia

- Rhineland Palatinate

- Saxony-Anhalt

- Schleswig-Holstein

- Liechtenstein

- Lake Skadar

- Netherlands

Central Russia

- Eastern Siberia

- Northwest Russia

- Russian Arctic

- Russian Far East

- South Russia

- Western Siberia

- Basque Country

- Fuerteventura

- Gran Canaria

- Castilla y Leon

- Castilla-La Mancha

- Extremadura

- Switzerland

- Avon & Bristol

- Bedfordshire

- Buckinghamshire

- Cambridgeshire & Peterborough

- Gloucestershire

- Greater London

- Greater Manchester

- Herefordshire

- Hertfordshire

- Isle of Wight

- Isles of Scilly

- Leicestershire & Rutland

- Lincolnshire

- Northamptonshire

- Northumberland

- Nottinghamshire

- Oxfordshire

- Staffordshire

- Warwickshire

- West Midlands

- Worcestershire

- Yorkshire – East

- Yorkshire – North

- Yorkshire – South

- Yorkshire – West

- Isle of Man

- Angus & Dundee

- Clyde Islands

- Dumfries & Galloway

- Isle of May

- Moray & Nairn

- North-east Scotland

- Orkney Isles

- Outer Hebrides

- Perth & Kinross

- Upper Forth

- Brecknockshire

- Caernarfonshire

- Carmarthenshire

- Denbighshire

- East Glamorgan

- Meirionnydd

- Montgomeryshire

- Pembrokeshire

- Radnorshire

- Vatican City

- Vancouver Island

- New Brunswick

- Newfoundland

- Northwest Territories

- Prince Edward Island

- Saskatchewan

- Aguascalientes

- Baja California

- Baja California Sur

- Mexico City

- Quintana Roo

- San Luis Potosí

- St Pierre & Miquelon

- Connecticut

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Rio Grande Valley

- West Virginia

- Buenos Aires City

- Buenos Aires State

- Santiago del Estero

- Tierra del Fuego

- Espírito Santo

- Federal District

- Mato Grosso

- Mato Grosso do Sul

- Minas Gerais

- Rio de Janeiro State

- Rio Grande do Norte

- Rio Grande do Sul

- Santa Catarina

- Easter Island

- Northern Ecuador

- French Guiana

- Saudi Arabia

- Farne Islands

- Birding Tour Companies

- Bird Fairs & Festivals

- Trip Report Repositories

- Weather & Tides

- Rarity Alerts

- Ornithological Journals

- Birding Magazines

- Websites with Mega-links

- Books for Birders

- Bird Book Publishers

- Software, DVDs, Recordings etc.

- Bird Writers

- Bird Art & Artists

- Digiscoping

- Photos, Photography & Photographers

- Webcams & Nestcams

- #12348 (no title)

- #11964 (no title)

- Bird Watching Books

- Bird Watching Telescopes

- Birdfeeders, Birdhouses etc

- Optics Retailers

- Optics Companies

- Outdoor Clothing for Birders

- Other Birding Equipment & Accessories

- Tripod Companies

- Banding or Ringing

- Study & Bird Behaviour

- Birders & Ornithologists

- Threatened & Extinct Species

- Conservation

- Ornithology Courses

- Identification

- Invasive Species

- Taxonomy & Bird Names

- Acanthisittidae – New Zealand Wrens

- Acanthizidae – Australasian Warblers

- Acrocephalidae – Reed & Brush Warblers Etc.

- Aegithalidae – Bush Tits

- Aegithinidae – Ioras

- Alaudidae – Larks

- Arcanatoridae – Dapple-throat & Allies

- Artamidae – Woodswallows, Butcherbirds & Currawongs

- Atrichornithidae – Scrub-birds

- Bernieridae – Malagasy Warblers

- Bombycillidae – Waxwings

- Buphagidae – Oxpeckers

- Calcariidae – Longspurs & Snow Buntings

- Callaeidae – Kokako & Saddlebacks

- Campephagidae – Cuckooshrikes, Cicadabirds, Trillers & Minivets

- Cardinalidae – Cardinals, Grosbeaks & Allies

- Certhiidae – Treecreepers

- Cettidae – Bush Warblers, Tesias & Allies

- Chaetopidae – Rockjumpers

- Chloropseidae – Leafbirds

- Cinclidae – Dippers

- Cisticolidae – Cisticolas, Prinia, Tailorbirds & Allies

- Climacteridae – Australasian Treecreepers

- Cnemophilidae – Satinbirds

- Coerebidae – Bananaquit

- Conopophagidae – Gnateaters

- Corcoracidae – Australian Mudnesters

- Corvidae – Crows, Jays, Magpies & Allies

- Cotingidae – Cotingas, Fruiteaters & Allies

- Dasyornithidae – Bristlebirds

- Dicaeidae – Flowerpeckers

- Dicruridae – Drongos

- Donacobiidae – Donacobius

- Dulidae – Palmchat

- Elachuridae – Spotted Wren-babbler

- Emberizidae – Buntings, New World Sparrows & Allies

- Erythroceridae – Yellow Flycatchers

- Estrildidae – Waxbills, Munias & Allies

- Eulacestomatidae – Ploughbill

- Eupetidae – Rail-Babbler

- Eurylaimidae – Broadbills

- Formicariidae – Antthrushes

- Fringillidae – Finches, Seedeaters, Euphonias & Allies

- Furnariidae – Ovenbirds

- Grallariidae – Antpittas

- Hirundinidae – Swallows & Martins

- Hyliotidae – Hyliotas

- Hylocitreidae – Yellow-flanked Whistler

- Hypocoliidae – Hypocolius

- Icteridae – Oropendolas, Orioles, Blackbirds & Allies

- Ifritidae – Blue-capped Ifrit

- Incertae Sedis – Uncertain Families

- Irenidae – Fairy-bluebirds

- Laniidae – Shrikes

- Leiothrichidae – Turdoides Babblers, Laughingthrushes, Barwings & Sibias

- Locustellidae – Grassbirds & Allies

- Machaerirhynchidae – Boatbills

- Macrosphenidae – Crombecs, Longbills & African Warblers

- Malaconotidae – Bushshrikes, Tchagras, Puffbacks & Boubous

- Maluridae – Australasian Wrens

- Melampittidae – Melampittas

- Melanocharitidae – Berrypeckers & Longbills

- Melanopareiidae – Crescent-chests

- Meliphagidae – Honeyeaters

- Menuridae – Lyrebirds

- Mimidae – Mockingbirds, Thrashers & Allies

- Mohoidae – O’os

- Mohouidae – Whitehead, Yellowhead & Brown Creeper

- Monarchidae – Monarchs, Paradise Flycatchers & Allies

- Motacillidae – Longclaws, Pipits & Wagtails

- Muscicapidae – Old World Flycatchers

- Nectariniidae – Sunbirds & Spiderhunters

- Neosittidae – Sitellas

- Nicatoridae – Nicators

- Notiomystidae – Stitchbird

- Oreoicidae – Australasian Bellbirds

- Oriolidae – Old World Orioles, Pitohuis & Figbirds

- Orthonychidae – Logrunners & Chowchilla

- Pachycephalidae – Whistlers & Allies

- Panuridae – Bearded Reedling

- Paradisaeidae – Birds-of-paradise

- Paramythiidae – Painted Berrypeckers

- Pardalotidae – Pardalotes

- Paridae – Tits & Chickadees

- Parulidae – New World Warblers

- Passeridae – Old World Sparrows

- Pellorneidae – Fulvettas, Ground Babblers & Allies

- Petroicidae – Australasian Robins

- Peucedramidae – Olive Warbler

- Philepittidae – Asities

- Phylloscopidae – Leaf Warblers & Allies

- Picathartidae – Rockfowl

- Pipridae – Manakins

- Pittidae – Pittas

- Pityriaseidae – Bristlehead

- Platysteiridae – Wattle-eyes & Batises

- Ploceidae – Weavers, Widowbirds & Allies

- Pnoepygidae – Wren-babblers

- Polioptilidae – Gnatcatchers

- Pomatostomidae – Australasian Babblers

- Prionopidae – Helmetshrikes

- Promeropidae – Sugarbirds

- Prunellidae – Accentors

- Psophodidae – Whipbirds, Jewel-babblers & Quail-thrushes

- Ptilogonatidae – Silky-flycatchers

- Ptilonorhynchidae – Bowerbirds & Catbirds

- Pycnonotidae – Bulbuls

- Regulidae – Goldcrests & Kinglets

- Remizidae – Penduline Tits

- Rhagologidae – Mottled Berryhunter

- Rhinocryptidae – Tapaculos

- Rhipiduridae – Fantails

- Sapayoidae -Sapayoa

- Scotocercidae – Streaked Scrub Warbler

- Sittidae – Nuthatches

- Stenostiridae – Fairy Flycatchers

- Sturnidae – Starlings, Mynas & Rhabdornis

- Sylviidae – Sylviid Babblers, Parrotbills & Fulvettas

- Tephrodornithidae – Woodshrikes & Allies

- Thamnophilidae – Antbirds

- Thraupidae – Tanagers & Allies

- Tichodromidae – Wallcreeper

- Timaliidae – Babblers

- Tityridae – Tityras, Becards & Allies

- Troglodytidae – Wrens

- Turdidae – Thrushes

- Tyrannidae – Tyrant Flycatchers

- Urocynchramidae – Przevalski’s Finch

- Vangidae – Vangas

- Viduidae – Indigobirds & Whydahs

- Vireonidae – Vireos, Greenlets & Shrike-babblers

- Zosteropidae – White-eyes, Yuhinas & Allies

- Accipitridae – Kites, Hawks & Eagles

- Aegothelidae – Owlet-nightjars

- Alcedinidae – Kingfishers

- Alcidae – Auks

- Anatidae – Swans, Geese & Ducks

- Anhimidae – Screamers

- Anhingidae – Darters

- Anseranatidae – Magpie Goose

- Apodidae – Swifts

- Apterygidae – Kiwis

- Aramidae – Limpkin

- Ardeidae – Herons, Egrets & Bitterns

- Balaenicipitidae – Shoebill

- Brachypteraciidae – Ground Rollers

- Bucconidae – Puffbirds

- Bucerotidae – Hornbills

- Bucorvidae – Ground Hornbills

- Burhinidae – Thick-knees & Stone Curlews

- Cacatuidae – Cockatoos

- Capitonidae – New World Barbets

- Caprimulgidae – Nightjars & Nighthawks

- Cariamidae – Seriemas

- Casuariidae – Cassowaries

- Cathartidae – New World Vultures

- Charadriidae – Plovers, Lapwings & Dotterels

- Chionidae – Sheathbill

- Ciconiidae – Storks

- Coliidae – Mousebirds

- Columbidae – Doves & Pigeons

- Coraciidae – Rollers

- Cracidae – Chachalacas, Curassows & Guans

- Cuculidae – Old World Cuckoos

- Diomedeidae – Albatrosses

- Dromadidae – Crab Plover

- Dromaiidae – Emu

- Eurypygidae – Sunbittern

- Falconidae – Falcons, Kestrels & Caracaras

- Fregatidae – Frigatebirds

- Galbulidae – Jacamars

- Gaviidae – Divers or Loons

- Glareolidae – Coursers & Pratincoles

- Gruidae – Cranes

- Haematopodidae – Oystercatchers

- Heliornithidae – Finfoots & Sungrebe

- Hemiprocnidae – Treeswifts

- Hydrobatidae – Northern Storm Petrels

- Ibidorhynchidae – Ibisbill

- Indicatoridae – Honeyguides

- Jacanidae – Jacanas

- Laridae – Gulls, Terns & Skimmers

- Leptosomatidae – Cuckoo Roller

- Lybiidae – African Barbets

- Megalimidae – Asian Barbets

- Megapodiidae – Megapodes

- Meropidae – Bee-eaters

- Mesitornithidae – Mesites

- Momotidae – Motmots

- Musophagidae – Turacos, Plantain-eaters & Go-away-birds

- Numididae – Guineafowl

- Nyctibiidae – Potoos

- Oceanitidae – Austral Storm Petrels

- Odontophoridae – New World Quails

- Opisthocomidae – Hoatzin

- Otididae – Bustards, Floricans & Korhaans

- Pandionidae – Ospreys

- Pedionomidae – Plains Wanderer

- Pelecanidae – Pelicans

- Pelecanoididae – Diving Petrels

- Phaethontidae – Tropicbirds

- Phalacrocoracidae – Cormorants & Shags

- Phasianidae – Pheasants, Grouse, Partridges & Allies

- Phoenicopteridae – Flamingos

- Phoeniculidae – Wood Hoopoes & Scimitarbills

- Picidae – Woodpeckers

- Pluvianellidae – Magellanic Plover

- Pluvianidae – Egyptian Plover

- Podargidae – Frogmouths

- Podicipedidae – Grebes

- Procellariidae – Petrels, Diving Petrels & Shearwaters

- Psittacidae – African & New World Parrots

- Psittaculidae – Old World Parrots

- Psophiidae – Trumpeters

- Pteroclidae – Sandgrouse

- Rallidae – Rails, Crakes, Gallinules & Coots etc.

- Ramphastidae – Aracari, Toucans & Toucanets

- Recurvirostridae – Avocets & Stilts

- Rheidae – Rheas

- Rhynochetidae – Kagu

- Rostratulidae – Painted Snipe

- Sagittariidae – Secretarybird

- Sarothruridae – Flufftails

- Scolopacidae – Woodcock, Snipe, Sandpipers & Allies

- Scopidae – Hammerkop

- Semnornithidae – Toucan Barbets

- Spheniscidae – Penguins

- Steatornithidae – Oilbird

- Stercorariidae – Skuas or Jaegers

- Strigidae – Owls

- Strigopidae – New Zealand Parrots

- Struthionidae – Ostriches

- Sulidae – Gannets & Boobies

- Thinocoridae – Seedsnipe

- Threskiornithidae – Ibises & Spoonbills

- Tinamidae – Tinamous

- Todidae – Todies

- Trochilidae – Hummingbirds

- Trogonidae – Trogons & Quetzals

- Turnicidae – Buttonquails

- Tytonidae – Barn & Grass Owls

- Upupidae – Hoopoes

- Big Days & Bird Races

- Apocryphal Birding Stories & Urban Myths

- Bird Humour

- Listing & Listers

- Twitching & Twitchers

- Hints & Tips

- Angling & Birds

- Gardening For Birders

- Birding Blogs

- Accessible Birding

- Birding Organisations

- Birds on Stamps

- Fatbirder’s Birding Advice

Birding Central Russia

By Central Russia we mean the heartland around Moscow consisting of 18 federal areas; the ‘Oblasts’ of Bryansk, Belgorod, Vladmir, Voronezh, Ivanovo, Kaluga, Kostroma, Kursk, Lipetsk, Moscow, Novogorod, Orel, Ryazan, Smolensk, Tambov, Tver, Tula, Yaroslavyl and the City of Moscow (The city of Moscow is not Oblast, but unlike capital cities of other oblasts it is absolutely independent from the Oblast government).

The total area of this part of Russia is 650,700 square kilometers; the population is 36,951,800 people, of whom 29,100,900 live in cities. Over 40 % of the population lives in the City of Moscow and the Moscow region (oblast). This is the most developed area of Russia. Occupying only 3.8% of Russia it is home for 25.4% of population of the country. It is on the leading edge in both social and economical development among remaining 6 Federal Districts of Russia.

This Federal District has a moderate continental climate and covers several natural zones from North to South – coniferous woods, dense woods, forest-steppe and steppe. Areas covered with woods ranges from 60% in the North to 5% in the South. The main terrain type is plain with hills of various sizes and heights. However, there are swamps in the north and da eveloped network of rivers, lakes and ponds make it rather diverse in habitat and appearance.

The variety of birds in the region largely overlaps with the general avifauna of Europe, but it is more diverse than individual European countries. Birding is not developed in this region, in line with Russia in general, either as an individual hobby or as an industry. That is why, for travelling birders it is advisable to find a local person who may assist you in finding your way around, and getting to the birds.

There are numerous good birding spots around the City of Moscow and in the whole district. Most of them are territories of national parks or nature reserves. However, because of long distances, it is difficult to see a lot in a short period of time. The best season for birding is Spring-Summer (from early May to mid June), further on, in the summer nesting period birding is less rewarding, but it takes off again in the period of autumn migration (September-October) which creates a fascinating opportunity to observe considerable number of bird species in one day.

Birding Smolensk If you need to visit Smolensk on business there are several interesting areas to bird.Smolensk Lake (about a mile to the south of the city is a large lake approx 1Km x 2Km. There is a large power station situated on the northern shore. To the south of the lake is a large reed bed, and an adjacent, smaller, more vegitated lake).Lakes near Przhevalskoye About 50 miles north of Smolensk there are some lakes which are a popular day trip destination for the residents of Smolensk. There is a bus service, and it is possible to stay at several homes by the small town of Przhevalskoye (named after the famous Russian naturalist explorer. The small museum dedicated to him is well worth a visit ).The tiny village of Veyeno, which is about 30 Km east of Smolensk just south of the main Smolensk – Moscow motorway.Highlights include: Bittern, White Stork, olden Eagle, Lesser=spotted Eagle, Montague’s Harrier, Honey Buzzard, Goshawk, Hazel Grouse, Quail, Whiskered Tern, Black Woodpecker, White-backed Woodpecker, Citrine Wagtail, Penduline Tit, Nutcracker, Golden Oriole, Common Rosefinch, Savi’s Warbler, Marsh Warbler, Icternine & Booted Warbler etc.

Bryansky Les Reserve

Ugra national park, zhuravlinaya roina reserve, andrey nedossekin.

Moscow | [email protected]

Olga Batova

Ornithologist - Ecological Travel Center - Moscow | [email protected]

Pavlo Zaltowski

Atlas - Birds of Moscow City and the Moscow Region

State darwin museum of natural history - moscow, rbcu - central chernozemie branch, rbcu - moscow branch.

Abbreviations Key

NR Bryansky Les

Nr zhuravlinaya rodina, 2006 [06 june] - paul mollatt - suzdal, birds of obninsk, tits of the moscow region.

Fatbirder - linking birders worldwide... Wildlife Travellers see our sister site: WAND

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Sweepstakes

- Intelligent Traveler

The Best North American Destinations for a Bird-watching Trip — and Our Tips for Having the Best Time in Each

These crowd-pleasing North American destinations are as perfect for bird-watching as they are for a good old-fashioned vacation.

COURTESY OF THE ATCHAFALAYA NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Perhaps you’ve heard about the bird-watching boom? Newcomers are flocking to the hobby, which studies have shown has the power to boost happiness. Another upside: unlike many outdoorsy pursuits, this one requires little in the way of specialized equipment or physical fitness.

Serious aficionados often plan their vacations around migrations, visiting spring hot spots such as Nebraska’s Platte River Valley or the shores of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. But if you’re still easing into the hobby — or traveling with friends or relatives who don’t know a warbler from a woodpecker — these five alternatives have plenty to offer in addition to bird-watching bliss.

STUART THURLKILL/COURTESY OF THE GREEN O

blickwinkel / Alamy Stock Photo

Greenough, Montana

Bird-watchers appreciate western Montana’s avian biodiversity; it’s particularly known for its populations of greater sage grouse, golden eagles, and Bohemian waxwings. The family-friendly Resort at Paws Up and its luxe, adults-only sibling property the Green O grant guests access to trails through 37,000 acres of wilderness. About 30 minutes away in Missoula, the 42-acre Greenough Park is another destination for bird spotters, with robust signage detailing local species.

Bragging Rights

The northern pygmy-owl is an adorable but ruthless carnivore that snacks on songbirds.

Besides the Birds

Both Paws Up and Green O offer a huge array of other outdoor activities, including horseback riding, rappelling, and guided fly-fishing for experienced anglers as well as those just learning to cast.

Cassie Wright/Courtesy of The Lodge on Little St. Simons Island

HOWARD CHEEK/GETTY IMAGES

Little St. Simons Island, Georgia

Accessible only by boat, this privately owned island is home to the Lodge on Little St. Simons Island . It is also part of the Golden Isles, one of the most important coastal conservation areas on the Eastern Seaboard. With rookeries of boisterous wading birds and a beach full of plovers, it’s perfect for “hard-core birders,” says Little St. Simons naturalist manager Nate Ramey. “But others can relax on our seven miles of beaches — which you only have to share with twenty or thirty other people,” because they’re open only to guests.

Rainbow-colored painted buntings are big on the island, as are wood storks. “They were a protected species, but now they’ve bounced back dramatically,” Ramey says of the long-legged wader. “It’s a testament to conservation.”

In addition to the beaches, the island has a network of hiking trails, while overnight guests can borrow bikes and fishing gear. In July, the island-wide bloom of hibiscus grandiflorus draws gardening geeks from around the U.S.

BUTCH LOMBARDI/COURTESY OF AUDUBON SOCIETY OF RHODE ISLAND

Cal Vornberger/Alamy Stock Photo

Bristol, Rhode Island

This scenic bayside village between Newport and Providence is home to intriguing species such as the wading willet and the iridescent purple martin, depending on the season. Spotting them is made easier by the boardwalks at the Audubon Nature Center & Aquarium and the hiking route at the Osamequin Nature Trails & Bird Sanctuary.

The saltmarsh sparrow may look like an everyday songbird, but this species, which nests at Jacob’s Point Preserve, is at risk of habitat loss as sea levels rise.

Bristol’s waterfront Blithewold estate has 33 acres of manicured gardens surrounding a historic mansion. In nearby Newport, the famed Cliff Walk gives a glimpse of the Gilded Age; spend the night at The Vanderbilt, Auberge Resorts Collection , where the 33 stylish rooms and suites are fresh off a two-year renovation.

SIMONE MONDINO/COURTESY OF WICKANINNISH INN

Don White / Alamy Stock Photo

Vancouver Island, BC

Summer is the best time to visit this densely forested destination, where the “fall” migration season starts as early as July for some species. Along the island’s serene eastern coast, check out the BC Bird Trail between Parksville and Qualicum Beach, where black oystercatchers, tufted puffins, and bald eagles are commonly seen. On the wild western coast, between Tofino and Ucluelet, visitors can spot soaring albatross while scouting for humpback whales, orcas, and other marine life. “May and September are also prime time for migrating seabirds,” says Mark Maftei, executive director of the Raincoast Education Society. “The nearshore and offshore waters host hundreds of thousands of waterfowl and seabirds that are moving up or down the coast in those months,” he adds.

Despite only weighing the equivalent of four nickels, the plucky western sandpiper migrates thousands of miles between Alaska and South America.

Outdoor adventures of all sorts can be had on the island. Milner Gardens & Woodland , on the eastern coast near the BC Bird Trail, has a “hidden” teahouse and trails that thread through its 70 acres of gardens and forest. In Tofino, the oceanfront Wickaninnish Inn is a family-owned Relais & Châteaux property known for its fireplaces and the dramatic views from its picture windows.

ARTHUR MORRIS/GETTY IMAGES

Lafayette, Louisiana

About a two-hour drive west of New Orleans, this city is the gateway to Cypress Island Preserve and Rip Van Winkle Gardens, both prime springtime habitats for bitterns, rails, and grebes. The broader Atchafalaya National Heritage Area surrounding Lafayette is home to five-inch-tall prothonotary warblers, with their bright-yellow feathers, and the five-foot-tall whooping crane, one of the rarest birds in North America.

With pink plumage reminiscent of a 1980s bridesmaid’s dress, the roseate spoonbill is a wading bird with a large, ladle-shaped beak.

This is the land of crawfish and zydeco, where every meal is an occasion. Dive in at Spoonbill Watering Hole & Restaurant , a James Beard Award nominee inside a refurbished Conoco station in Lafayette, where the motto is “Tastes like good times.” Maison Madeleine is a characterful alternative to the chain hotels in the area.

A version of this story first appeared in the July 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Bring the Binoculars."

Book Your Own Birding Trip

In collaboration with tour guide operator partners, the National Audubon Society is proud to offer suggested travel itineraries throughout the Caribbean and Latin America. These beautiful trips are packed with tremendous birding experiences in sites where Audubon is on-the-ground and actively engaged in conservation work. Click on one of the cards below to learn more.

Audubon has partnered with Rockjumper on Impact Adventures, a suite of international birding itineraries aimed at driving sustainable tourism in select biodiverse hotspots.

Audubon has partnered with Holbrook Travel on Flyway Expeditions, a series of birding trips that support conservation work in Latin America and in the Caribbean.

Across Latin America and the Bahamas, Audubon works closely with locals to build sustainable ecotourism opportunities.

Why Hire a Local Bird Guide?

By using a local guide, you ensure that tourism revenue stays in the country to improve the local economy. Our partner organizations below can put you in contact with local guides and tour operators that have first-hand knowledge of the area and can accomodate specific needs.

The Bahamas Bahamas National Trust Nassau, The Bahamas 1-866-978-4838 Email | Website

More information:

Bahamas.com Birding Guide

Paraguay Guyra Paraguay Asuncion, Paraguay Phone: (595 21) 229 097 Email | Website

More information: Aviturismo Paraguay

Belize Belize Audubon Society Belize City, Belize 501-223-4985 Email | Website

Guatemala Asociacion Vivamos Mejor Panajachel, Guatemala Phone: (502) 7762-0159/0160 Email | Website

Wildlife Conservation Society Guatemala Flores, Guatemala Phone: 502 7867-5152 Email | Website

More information: Bird Zone Atitlan

For more information or additional help, contact:

Audubon Americas National Audubon Society Washington, DC Email | Website

The National Audubon Society is not an official tour organizer, nor are we endorsing any of the tour operators listed above or hotels listed in the itineraries. The list of tour operators is by no means exhaustive and will be updated as we become familiar with more providers.

Get Audubon in Your Inbox

Let us send you the latest in bird and conservation news.

Bird-watching tourism

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2015

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Rochelle Steven 3 &

- Darryl Jones 4

173 Accesses

- Protected Area Tourism

- North American Participants

- Diverse Avifauna

- Wildlife Tourism

- Sustainable Tourism

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Biggs, D., J. Turpie, C. Fabricius, and A. Spenceley 2011 The Value of Avitourism for Conservation and Job Creation – An Analysis from South Africa. Conservation and Society 9:80-90.

Article Google Scholar

Connell, J. 2009 Birdwatching, Twitching and Tourism: Towards an Australian Perspective. Australian Geographer 40(2):203-217.

Green, R., and D. Jones 2010 Practices, Needs and Attitudes of Bird-watching Tourists in Australia. Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism. Brisbane: Griffith University.

Google Scholar

Higham, J. 1998 Tourists and Albatrosses: The Dynamics of Tourism at the Northern Royal Albatross Colony, Taiaroa Head, New Zealand. Tourism Management 19:521-531.

Moss, S. 2004 A Bird in the Bush: A Social History of Birdwatching. London: Aurum.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Gold Coast campus, Southport, 4215, Australia

Rochelle Steven

Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan campus, 4111, Nathan, Australia

Darryl Jones

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rochelle Steven .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Hospitality Leadership, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, Wisconsin, USA

Jafar Jafari

School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Honggen Xiao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Steven, R., Jones, D. (2014). Bird-watching tourism. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_18-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_18-1

Received : 14 November 2014

Accepted : 14 November 2014

Published : 24 September 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Listing and Taxonomy

American Birding Association Checklist Committee (CLC) Report, March 2024

ABA Area Field Guides

The American Birding Association Field Guides each include hundreds of species birders are most likely to see in their state or province. Illustrated with crisp, color photographs, they include descriptions of each bird along with tips of when and where to see them, and are written by local expert birders.

- Welcome New Birders!

- Birding News

- ABA Checklist

- Listing & Taxonomy

- ABA Field Guides

- ABA Rare Bird Alert

- Festivals & Events

- Birding Clubs & Organizations

- ABA Area Birding Trails

- Listing Central

- ABA Code of Birding Ethics

Latest Podcast, Articles, & More…

08-13: This Month in Birding – March 2024

Peter Kaestner Breaks the 10,000 Bird Barrier!

Rare bird alert.

Rare Bird Alert: March 29, 2024

Field ornithology.

First Red-flanked Bluetail in the Eastern ABA Area

- Book Reviews

The Fight to Protect the Birds

March 2024 Photo Quiz

How to know the birds.

How to Know the Birds: No. 81, A Kinglet Assist from Merlin

Birds and....

No. 25: Birds and Nests

- Birding Magazine

Birding Online: March 2024

North American Birds

North American Birds: Vol. 74, No. 2

Section home pages.

- American Birding Podcast

- NAB Regional Reports

- Identification

- ABA Publications Archive

- ABA Young Birders

ABA Young Birder Program includes ABA Young Birder Camps, the ABA Young Birder Mentoring Program, and the young birder magazine, The Fledgling.

When you travel with ABA, you help build a better future for birds, birders, and birding. We combine great field birding, amazing destinations, and cultural immersion, while supporting local communities.

Birders’ Exchange provides birdwatching equipment and resources to organizations in the United States, Canada, Latin America, and the Caribbean with an educational need.

The American Birding Association is proud to partner with Thanksgiving Coffee Company to bring you Song Bird Coffee. Song Bird is grown on small farms that have been certified Bird-Friendly by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, the gold standard for shade-grown, organic coffees.

ABA Community Weekends

ABA Community Weekends bring birders together near you! With the help of local friends and partners, we offer guided bird walks, workshops, and gatherings in cities across the U.S. and Canada and it’s free to participants.

- Travel and Events

- Birders’ Exchange

- ABA Song Bird Coffee

The ABA is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that inspires all people to enjoy and protect wild birds.

Please join us as we leverage our extensive knowledge, expertise, connections, and world-class content to bring more people into the birding community.

- My Membership

- Join ABA Community

- Flight Calls newsletter

- Matching Gifts

- Gift Planning

- Search for:

- WooCommerce Cart 0

When you travel with the American Birding Association, you help build a better future for birds, birders, and birding. Our thoughtfully designed program combines great field birding, amazing destinations, and cultural immersion, while visibly supporting local projects and communities. We help the birding world effectively work toward on-the-ground conservation and sustainable development, furthering ABA’s ongoing commitment to inspire all people to enjoy and protect wild birds. We invite you to join us in making a positive difference while enjoying some of the world’s best birding.

Upcoming Tours

2024 Bird of the Year Tour: Sax-Zim Bog and Northern Minnesota

June 13-17, 2024 Join our 2024 Bird of the Year tour in Sax-Zim Bog, Northern Minnesota. In the warmth of summer, the Bog bursts with life, as it is a breeding ground for many songbirds, including our Bird of the Year: Golden-winged Warbler! We are thrilled to announce that cover artist Natasza Fontaine will be joining us, too, for some fun and interactive art workshops during the tour. Don’t miss out on this exciting birds and art tour to one of the prettiest wilderness areas in the United States.

Belize birding tour

March 22-31, 2024

Hawaiʻi birding tour

April 2-11, 2024

Newfoundland Adult Birder Camp – FULL!

June 2-8, 2024

Borneo birding tour

Aug. 27-Sep. 6, 2024

Central and Northern Argentina birding tour

October 3-16, 2024

Dominican Republic birding tour

December 6-15, 2024

Recent Trip Reports

2022 Kenya Trip Report

American Birding Association 2022-09-28T13:00:23-04:00 September 27th, 2022 |

We enjoyed 11 glorious days traveling to three very different areas of Kenya: Samburu, Buffalo Springs and Shaba Game Reserves in the dry northern region; Lake Nakuru National Park in the rift read more >>

2022 Adult Birder Camp West Virginia Trip Report

Katinka Domen 2022-09-28T13:14:55-04:00 August 17th, 2022 |

Day One We began our first full day at a privately-owned farm field that is left uncut until the higher-altitude grassland birds finish breeding. The stars of the show were the Bobolinks. read more >>

2022 Bird of the Year Southeast Arizona Trip Report

Katinka Domen 2022-09-28T13:20:28-04:00 September 12th, 2022 |

Our friends thought we were crazy to head to Southeast Arizona in July! I had a few concerns myself, but off we went. Turns out, the weather in the canyons and higher read more >>

COVID-19 VACCINATION VERIFICATION POLICY FOR ABA TRAVEL AND EVENTS

Until further notice, COVID-19 vaccination is a requirement to participate in any and all ABA Travel. Exact vaccination requirements are dependent on country of residence, country(ies) visited, and other laws, rules, and regulations of local vendors. The ABA will do its best to communicate with you after booking, and prior to travel, as rules are subject to change. Acceptable proof of COVID-19 vaccination includes a certificate issued at national or subnational level or by an authorized vaccine provider (e.g., the CDC vaccination card) , v accination certificate with QR code , digital pass via smartphone application with QR code (e.g., United Kingdom National Health Service COVID Pass, European Union Digital COVID Certificate), digital photos of vaccination card or record, downloaded vaccine record or vaccination certificate from official source (e.g., public health agency, government agency, or other authorized vaccine provider), or a mobile phone application without QR code . All forms of proof of COVID-19 vaccination must have all of the following (i) personal identifiers including full name plus at least one other identifier such as date of birth or passport number that match the personal identifiers on the passenger’s passport or other identity documents; (ii) the name of official source issuing the record (e.g., public health agency, government agency, or other authorized vaccine provider; and (iii) vaccine manufacturer and date(s) of vaccination. Requirement for boosters or additional vaccination is subject to state, federal, and national guidelines, rules and requirements applicable to your country of citizenship, and countries visited during ABA Travel.

Birding (Yes, Birding) Is a Multi-Billion Dollar Ecotourism Industry

Photo illustration by Sarah Rogers/The Daily Beast

Millions of birders around the world set out to catch a rare glimpse of plumage, a bold stroke of color, or to hear an unusual song—and they're changing the face of tourism.

Brandon Withrow

I will never forget the first time I got lost in the eyes of a ruby-throated hummingbird. It was late in spring seven years ago and I was writing out on our patio. Flashes of her green back cut through our garden, darting from petunia to petunia. My eyes shifted up from the laptop, finding her only inches away. We briefly stared quietly at each other, frozen in time at 53 beats per second.

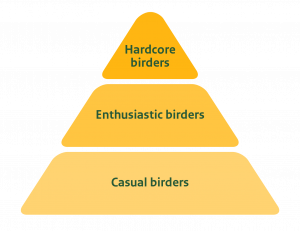

Over the years, while I’ve added feeders—seed, suet, and nectar—and enthusiastically packed my camera and binoculars for the nearest nature preserve, I’ve found that compared to serious birders, I’m still just a novice birder, or maybe just an avid bird-lover.

Determined birders are ornithological junkies, compelled to travel long distances by their love of spotting a rare species. In fact, they are part of a growing multi-billion dollar ecotourism industry. And birding, as it turns out, is not only the perfect excuse for travel, but also part of a practical global conservation effort to help both birds and humans thrive.

It is estimated that over $800 billion is spent a year in outdoor recreation in the United States, with birdwatching having an economic benefit of $41 billion dollars. Roughly $17.3 billion is spent annually in wildlife-watching trip-related expenses in the U.S., with more than 20 million Americans taking birding-specific trips.

Courtesy Brandon Withrow

One of those birding hotspots is the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, which I visited last October as part of a press trip to ride an extensive new cycling trail system.

This is a region that closely combines both the dry prairie landscape and the colorful tropical palette of the Gulf, bringing in a spectacle of birds that not only call this home, but make this a regular stop during migration. Here I first experienced the end-of-day cacophonous descent of red-crowned parrots into the trees.

Every November, the Birding Festival centered in Harlingen, Texas, brings in 2 million over a five-day event, with each birder hoping to tick off a large number of unique and exotic species on their avian bucket-list.

It was on this cycling trip that I met Dorian Anderson , one of the industry’s most passionate birders, with an incredible photographic eye . As we biked the region’s rail-trails, I could hear him identifying the call of birds.

Anderson is not your typical birder, however. With a doctorate in developmental genetics and post-doctoral work under his belt, he found himself falling in love with birding. In 2014, he spent a year on his bike traveling the country finding birds and blogging about it —he is currently writing a book about the experience.

Coutersy Brandon Withrow

“I wanted out from my career,” Anderson tells me, “and the bike trip was something sufficiently grand, sufficiently different, and sufficiently individualistic that I could go and do it. I don’t really work well in structures. That’s not really my style.”

Anderson figured that if he connected seven key areas across the country at the right time of the year, he could get in a list of 600 species. So he embarked on his road trip with no real cycling experience, getting 40 flats—until he finally bought kevlar tires. He rode in deep snow below freezing temperatures, was attacked by dogs, hit by a vehicle, and nearly struck by lightning. But he did meet fellow birders along the way, who helped him with supplies, places to stay.

“From an ecotourism standpoint,” says Dorian Anderson, “the Lower Rio Grande Valley has a great product. Birders are looking for species you can’t see in other places and the Rio Grande Valley is so good because you can see all of these Mexican birds there.” Anderson annually leads group tours for the festival.

Birders who travel large distances tend to do it in more traditional ways—they either fly into places like the Rio Grande Valley or take a road trip. They also tend to be baby boomers, those who are in a place in life that allows for disposable income and prolonged travel.

Since it brings in money, ecotourism is frequently seen as an incentive for protecting habitats and species.

“This is particularly true with birding ecotourism,” says Matthew Jeffery, the director of programs and deputy director (international) at the National Audubon Society , “because birding ecotourists typically have a lighter footprint from not wanting to disturb the birds and are often pioneers for furthering conservation projects to protect the habitats of wild and rare bird species.”

To that end of protecting habitats, organizations like the National Audubon Society are working on building birding-based ecotourism in developing countries. It is intended to be a win-win for those living there, protecting the area’s natural treasures and providing income.

“This can be seen in the Northern Colombia Birding Trail project from Audubon and its partners—Patrimonio Natural, the Asociación Calidris, and support from USAID,” says Jeffery. (This last summer, Anderson also helped the National Audubon Society develop birding itineraries for Colombia.)

Colombia is a birder paradise, with over 1900 bird species—more than anywhere else on the planet, with several only found in certain regions of the country. The country is the only home for eight species of hummingbird, including the stunning shimmering-green and purple-bearded Buffy Helmetcrest .

“This project trained 43 local guides with environmentally focused practices,” says Jeffery, “20 of which worked in bird-based tourism, and resulted in 53 percent of those working in bird-based tourism seeing an increase in their income.”

Projects like this create partnerships with local governments and by focusing on communities near important habitats, they help to form what he says are “buffer communities,” where they are “able to strengthen their involvement in conservation often resulting in a reduction of habitat degradation and sometimes restoration.”

Due to Audubon’s pragmatic approach, which builds its local programs off of trade-offs and economic incentives with local governments and representatives, they have not been without criticism from other conservationist organizations who find it too compromising.

Yet they have taken an approach that intends to move the needle when they can.

Birding ecotourism in smaller economies like Colombia becomes a way not only to find rare birds—at least for a Northern American or European birder—but also to use global adventures in lush natural habitats to infuse the dollars into developing regions through lodges or tour guides, making natural conservation efforts worthwhile to communities.

You don’t have to travel far, however, to find stunning birds—your backyard will do fine.

Jeffery notes that many in the United States DIY their birding. (In my own backyard, for example, I can find upwards of 20 species of birds—including goldfinches, cardinals, woodpeckers, and nuthatches—all at one time in the spring.)

Within communities across the country, it is frequently possible to find birding festivals within a short driving distance. These festivals help to bring in outside dollars.

In Northwest Ohio, for example, where habitat restoration projects and wildlife refuges are getting attention, birding has grown in leaps and bounds, making festivals like The Biggest Week in American Birding possible.

“The Biggest Week in American Birding festival, which will mark its tenth year next May, has put our region on the map internationally as one of the premier birding destinations in North America,” says Scott Carpenter, the director of public relations for Metroparks Toledo .

The festival is a chance to find the mass migration of approximately 20 colorful warbler species in one fell swoop, including water birds like egrets and the elegant great blue heron. Venturing away from these marshlands to the local woodlands, and an array of woodpeckers from the downy and hairy to the iconic red-crested pileated are possible.

“Over 20 years ago,” says Carpenter, “when I was an outdoors columnist for newspapers, birders and tourism professionals talked about the spring songbird migration and how it was the best kept secret in our region.”

When he would travel to Leamington, Ontario, he’d find banners along the streets welcoming birders.

“I found it strange that the south shore of Lake Erie didn’t receive that kind of notice,” Carpenter tells me. “After all, we have the same birds, earlier, and fantastic access to public lands where people can enjoy them. So, a few years ago, when I saw ‘Welcome Birders’ on banners lining the streets in my hometown of Oregon, Ohio, it was a dream realized. Black Swamp and Biggest Week made that happen.”

Sponsored by the Black Swamp Bird Observatory at Magee Marsh, the festival drew in approximately 90,000 people from 52 countries (six continents) in the spring of 2018, with birding bringing $40 million into the region annually.

The area hopes to keep capitalizing on these efforts, making others aware of their natural resources through new bike and hiking trails in the park system, camping, and water kayaking trails along the Maumee River, and the development of the Treehouse Village set to have its first guests next year.

Whether it’s birding festivals in Northwest Ohio or the Rio Grande Valley, or even hawk migrations in Cape May, NJ, or millions of sandhill cranes along the Platte River in Nebraska, birding ecotourism is big business in the United States and an emerging industry powerhouse for developing countries.

Globally, millions of birders like me set out for a chance to see that rare plumage, that bold stroke of color, or to hear that unusual song—even if not every species will visit you face-to-face and acknowledge your existence, like my hummingbird did.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here .

Twitchers reveal their top spots for birdwatching in the US

Nov 9, 2023 • 6 min read

The area around Tucson features a variety of habitats for birds, such as Saguaro National Park © G Parekh / Getty Images

Becoming a birder is easy – all you have to do is step outside.

Be it NYC's urban jungle or California's wild coast, birds are everywhere – and enjoying the winged wonders is free.

According to the US Fish & Wildlife Service , roughly 45 million Americans consider themselves birders – and during the pandemic, the number of avian enthusiasts soared. In 2020, downloads of online bird-identification apps like Merlin Bird ID and the National Audubon Society's Mobile Bird Guide doubled their usual rate. Sales of birding merchandise shot up nearly 50%. Even today, the popularity of birding shows no signs of fading.

“Birding shifts your perceptions, adding new layers of meaning and brokering connections: between sounds and seasons, across far-flung places, and between who we are as people and a wild world that both transcends and embraces us,” writes NYC-based birder Christian Cooper in his 2023 memoir Better Living Through Birding (a New York Times Bestseller). “In my life, it has been a window into the wondrous.”

But not all birding locations are equal – so we chatted with American bird specialists to find out which US destinations are top-tier for twitchers. Here are their recommendations.

1. Harlingen, Texas

The southern tip of Texas is tops for birding, particularly when Harlingen hosts the Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival during fall's migration season.

A good day of birding on the East Coast might mean spotting 50 to 60 species. In Harlingen, you might spot nearly 100 species after a few hours. Birders will appreciate the riot of breeding birds migrating south from places like Canada, but they'll lose their minds over colorful species from Central America and Mexico that sometimes visit the area.

With a list of endemic birds found nowhere else in the US, the Lone Star State has plenty of reasons to lose their minds year-round. Noteworthy residents include the green jay – which flashes brilliant emerald, saffron, and navy plumage – and the chachalaca. Although this pheasant-sized bird boasts the elegant profile of a tiny velociraptor, it screeches like a remedial trumpet player.

2. New York City, New York

Molly Adams, founder of the Feminist Bird Club , was surprised when she opened the app eBird and found that Brooklyn's Prospect Park is one of New York City's most ecologically rich hotspots for birdwatching. Although the pigeon reigns supreme on NYC's streets, it's got stiff competition in the 1700 parks around town.

New York City's urban green spaces provide a much-needed respite for over 200 species of migratory birds traveling throughout spring and fall. “These pocket parks are part of the Atlantic Flyway, so during migration, you can see close to 100 species in one day,” she explains.

Adams, who creates inclusive birdwatching opportunities for BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ folx and women, loves how long the birding season lasts in autumn. Still, there's nothing better birding-wise than going through the winter and having spring come," she says. “There are all these colorful birds.” Be it a scarlet tanager in Central Park or a ruby-throated hummingbird flitting through Jamaica Bay, America's most populous city boasts an equally dizzying amount of biodiversity. “It really invigorates my passion for birding,” Adams notes.

3. Toledo, Ohio

Toledo might not be high on most travelers' to-do lists, but the surrounding region is bar-none for birders visiting the Biggest Week in American Birding Festival . Lake Erie's southern shores become the unofficial warbler capital of the world every May as more than 300 species travel from South America to the Great White North.

Weary migrating warblers stop around Toledo to refuel before continuing across Lake Erie into Canada, and one of their favorite places to find refuge is the Magee Marsh Wildlife Are a. Visitors walk along a boardwalk to view the avian Elysium, and though it gets busy during spring migration, the crowds won't stop you from spotting dozens of winged wonders.

4. Point Reyes National Seashore, California

Thirty miles north of San Francisco , the San Andreas fault line splits the California coast in two to form the Point Reyes National Seashore. Rolling hills stretch to the east, ocean waves crash on unspoiled beaches to the west, and nearly 500 species of birds soar around the 70,000 acres of protected land year-round.

With abundant forests, estuaries and grasslands, this area is a winged wonderland for birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway. Of particular note is the endangered snowy plover, a small, cream-white creature that skitters along the shoreline. According to the National Audubon Society , many birders also check out nearby Bolinas Lagoon, “where a tidal estuary attracts waterfowl, wading birds, and, when the tide is right, large flocks of shorebirds.”

5. Everglades National Park, Florida

Gators may be the crowning glory of the Everglades , but North America's wading birds are also an essential part of Florida's wetlands ecosystem.

Kayakers and canoeists can float along the Gulf Coast's waters to watch egrets, ibis, and roseate spoonbills pick through the shallows for food. The biking and hiking trail at Shark Valley, a one-hour drive from Miami , also offers an easy escape from South Florida's suburban sprawl if you're looking for ornithological entertainment.

Winter is an ideal time to visit, as it offers “the highest diversity of birds and the best conditions for birding,” says Brian Rapoza, the Tropical Audubon Society's Field Trip Coordinator. “One of the season's highlights is when the swallow-tailed kites come back to Florida from their wintering grounds in Central and South America, usually in the second or third week of February.”

6. Tucson, Arizona

From Saguaro National Park to the nearby Chiricahua Mountains, Tucson and the surrounding area sport an abundance of species that can't be found anywhere else in the US. “It's a popular place for people who keep national lists with the number of birds they've seen in North America,” says Will Russell, owner of local bird tour company Wings .

While spring is prime birding time, July's monsoon season brings a set of international fliers to the region. “Hummingbirds that bred in Mexico disperse north, so instead of having six or seven kinds of hummingbirds, there are sometimes 12 or 13,” says Russell.

Birds aren't the only thing that makes Tucson's bird scene spectacular. “Tucson is a place where many bird people come to retire,” says Jennie MacFarland, Bird Conservation Biologist for the Tucson Audubon Society . “It's got a strong birding community.” Local birders can often be found at the Sweetwater Wetlands, scaling Mount Lemmon, or checking out the bird feeders in Madera Canyon.

7. Cape May, New Jersey

If Hitchcock's 1963 avian apocalypse thriller The Birds leaves you feeling queasy, skip Cape May during October's migration season. The Audubon festival's “So Many Birds” tagline is an understatement.

Birds migrating along the Atlantic Coast throughout spring and fall funnel into Cape May, a peninsula on the southern tip of New Jersey. The result is a feather-frenzied traffic jam. Whether watching warblers from the Cape May Migratory Bird Refuge or raptors along Higbee Beach, you can look at any point in the sky and eye 15-20 birds trying to figure out the next leg of their journey.

Perhaps the most magnificent creature to spot during this pandemonium is a peregrine falcon. While many birds struggle against whipping winds, peregrine falcons can cut across the horizon as if there's no wind at all. They seem elegant and assured – the calm amidst the chaos.

It's precisely the kind of serenity that makes birding so appealing.

This article was first published June 2020 and updated November 2023

Explore related stories

National Parks

Apr 3, 2024 • 6 min read

A trio of treasures, Florida’s national parks cater those who love everything wild and offbeat about the Sunshine State. Here’s all you need to know.

Apr 2, 2024 • 9 min read

Mar 26, 2024 • 5 min read

Mar 24, 2024 • 6 min read

Mar 23, 2024 • 9 min read

Mar 22, 2024 • 9 min read

Mar 22, 2024 • 5 min read

Mar 15, 2024 • 10 min read

Mar 5, 2024 • 5 min read

Featured Trips

These tours are Guaranteed Departures, or only need a couple more bookings to become guaranteed.

2025 Puerto Rico Escape – Endemics and Island Birding

2025 Minnesota – Sax-Zim Bog, Boreal Specialties, and Owls

2025 California – Northern California: Mountains, Ocean and Desert

2024 Northern Arizona – The Grand Canyon and Condors

Destinations.

We go where the birds are!

Worldwide Birding Tours available through

Details on the Birding Ecotours website!

Most popular tours.

Our most sought-after destinations

2024 Florida – South Florida Specialties and the Dry Tortugas

2025 Oregon – Klamath Basin & the Coast

2024 North Carolina – The Outer Banks

2024 California – Southern California Specialties

2025 Texas Winter — Whooping Cranes and Rio Grande

2024 oregon – klamath basin & the coast, meet the leaders.

Our highly trained and knowledgeable guides at your service!

Jacob Roalef

People who always support and endorse our work

Save big on upcoming tours!

Sign up to recieve discounts and the latest information on our unforgettable tours in the United States and Canada

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Small sight—Big might: Economic impact of bird tourism shows opportunities for rural communities and biodiversity conservation

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations National Audubon Society, Anchorage, Alaska, United States of America, Department of Environmental Science, Alaska Pacific University, Anchorage, Alaska, United States of America, Caurina Consulting LLC, Haines, Alaska, United States of America

- Tobias Schwoerer,

- Natalie G. Dawson

- Published: July 6, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268594

- Reader Comments

Birdwatching is considered one of the fastest growing nature-based tourism sectors in the world. Tourists who identify as birdwatchers tend to be well-educated and wealthy travellers with a specific interest in the places they visit. Birdwatchers can bring economic resources to remote communities diversifying their economies and contribute to biodiversity conservation in areas of bird habitat with global significance. Alaska plays a critical role in understanding the link between bird conservation and bird tourism as it supports the world’s largest concentration of shorebirds and is a global breeding hotspot for hundreds of migratory species, including many species of conservation concern for their decline across their ranges. Alaska is also a global destination for birders due to the large congregations of birds that occur during the spring, summer and fall seasons. Despite its global importance, relatively little information exists on the significance of bird tourism in Alaska or on opportunities for community development that align with conservation. This study used ebird data to look at trends in Alaska birdwatching and applied existing information from the Alaska Visitor Statistics Program to estimate visitor expenditures and the impact of that spending on Alaska’s regional economies. In 2016, nearly 300,000 birdwatchers visited Alaska and spent $378 million, supporting approximately 4,000 jobs. The study describes bird tourism’s contributions to local jobs and income in remote rural and urban economies and discusses opportunities for developing and expanding the nature-based tourism sector. The study points toward the importance of partnering with rural communities and landowners to advance both economic opportunities and biodiversity conservation actions. The need for new data collection addressing niche market development and economic diversification is also discussed.

Citation: Schwoerer T, Dawson NG (2022) Small sight—Big might: Economic impact of bird tourism shows opportunities for rural communities and biodiversity conservation. PLoS ONE 17(7): e0268594. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268594

Editor: Ricardo Bomfim Machado, University of Brasilia, BRAZIL

Received: December 28, 2021; Accepted: May 3, 2022; Published: July 6, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Schwoerer, Dawson. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The authors received funding for the study through the Edgerton Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Participation in U.S. nature-based outdoor recreation has increased over the past decade, continuing a long-term, upward trend [ 1 ]. Wildlife-related activities, especially wildlife viewing have increased by 20% between 2011 and 2016, outpacing participation in hunting and fishing [ 2 ]. Wildlife-related tourism can provide direct benefits to wildlife and wildlife conservation efforts if tourists engage as conservation partners during their activities within a given place [ 3 ]. As the conservation of biological diversity becomes a global priority in the face of climate change, opportunities exist to highlight the relationship between wildlife-related tourism, economic diversification for communities, and conservation action.

Among increasing wildlife-related tourists in the U.S., birdwatchers, also called birders, have seen steady increases in participation and are considered the world’s largest group of “eco-tourists” [ 4 ]. Birdwatchers can also include local residents within a community. Birding can be defined as “observation, identification, and photography of birds for recreational purposes” [ 5 ]. Birding tourism, like many wildlife tourism activities, requires interaction between a visitor and a local community and depends on the ecological integrity of a specific location to support the bird species that draw tourists to a particular place. Many of the places that draw birding tourism are also remote, requiring significant expenditures to access. Studies show that birding tourists tend to be well-educated, wealthy, and committed to their chosen tourism activity [ 6 ].

The growth and popularity of birding has provided new revenue to rural communities, regions, and countries [ 6 , 7 ]. Expenses related to wildlife viewing in the U.S. increased 29% from 2011 to 2018 [ 2 ]. In 2016, there were 45 million birders in the U.S. spending $39 billion on travel and equipment aimed at observing birds [ 6 ]. Thus, tourism experiences can be enhanced by the conservation activities within a given community that in turn strengthens a model of economic development based on ecological integrity. Growth in wildlife viewing is also happening at a time of unprecedented declines in global biodiversity [ 8 ]. Effective and immediate conservation action at a global scale is required to reduce and halt the decline [ 8 , 9 ].

Alaska, is one of the few remaining storehouses of intact habitat and complete wildlife assemblages. Thus, Alaska plays a central role in global conservation action [ 9 ]. It is home to the world’s largest concentration of shore birds and is a globally significant breeding hotspot for migratory birds. Alaska supports over one third of the world’s shorebird populations some of which breed nowhere else and are threatened by habitat loss and climate change [ 10 ].

Alaska’s high-quality bird habitat provides unmatched viewing opportunities for rare and threatened species. Over 550 species of birds have been documented across Alaska’s vast landscape [ 11 , 12 ]. Alaska also holds the most globally-significant Important Bird Areas (IBAs) of any U.S. state. Many of Alaska’s Important Bird Areas do not have conservation status and thus are not protected [ 13 ]. Yet, IBAs are essential places or habitat for birds’ nesting, foraging, and migrating [ 14 ].

While birds can be observed in Alaska year-round, the best birding season extends from May until September, overlapping with the presence of migratory birds for which Alaska serves as a globally important migratory stop-over and breeding ground [ 11 , 15 ]. Most birdwatchers visit Alaska in June followed by July and August [ 16 ]. Between 2001 and 2019, the number of users of ebird, a citizen science bird observation app, increased nine-fold for submissions in Alaska [ 17 ]. Similarly, the reported average birding effort per birder has increased from five submissions per birder in 2008 to over 40 submissions per birder in 2020 [ 17 ].