PoetryVerse

The Journey Of The Magi

A cold coming we had of it, Just the worst time of the year For a journey, and such a long journey: The ways deep and the weather sharp, The very dead of winter.' And the camels galled, sorefooted, refractory, Lying down in the melting snow. There were times we regretted The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, And the silken girls bringing sherbet. Then the camel men cursing and grumbling and running away, and wanting their liquor and women, And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters, And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly And the villages dirty and charging high prices: A hard time we had of it. At the end we preferred to travel all night, Sleeping in snatches, With the voices singing in our ears, saying That this was all folly. Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness, And three trees on the low sky, And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow. Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel, Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver, And feet kicking the empty wine-skins. But there was no information, and so we continued And arriving at evening, not a moment too soon Finding the place; it was (you might say) satisfactory. All this was a long time ago, I remember, And I would do it again, but set down This set down This: were we led all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death, But had thought they were different; This Birth was Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death. We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.

Feel free to be first to leave comment.

Journey of the Magi Summary & Analysis by T. S. Eliot

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

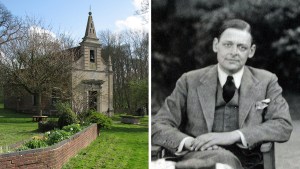

"Journey of the Magi" is a poem by T.S. Eliot, first published in 1927 in a series of pamphlets related to Christmas. The poem was written shortly after Eliot's conversion to the Anglican faith. Accordingly, though the poem is an allegorical dramatic monologue that inhabits the voice of one the magi (the three wise men who visit the infant Jesus), it's also generally considered to be a deeply personal poem. Indeed, the magus in the poem shares Eliot's view that spiritual transformation is not a comfort, but an ongoing process—an arduous journey seemingly without end. The magus's view on the birth of Jesus—and the shift from the old ways to Christianity—is complex and ambivalent.

- Read the full text of “Journey of the Magi”

The Full Text of “Journey of the Magi”

“journey of the magi” summary, “journey of the magi” themes.

Spiritual Death and Rebirth

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “journey of the magi”.

'A cold coming ... ... dead of winter.'

And the camels ... ... girls bringing sherbet.

Lines 11-16

Then the camel ... ... had of it.

Lines 17-20

At the end ... ... was all folly.

Lines 21-25

Then at dawn ... ... in the meadow.

Lines 26-31

Then we came ... ... might say) satisfactory.

Lines 32-36

All this was ... ... Birth or Death?

Lines 36-39

There was a ... ... Death, our death.

Lines 40-43

We returned to ... ... of another death.

“Journey of the Magi” Symbols

Biblical Imagery

- Line 23: “running stream”

- Line 24: “three trees on the low sky”

- Line 25: “an old white horse”

- Line 26: “vine-leaves”

- Line 27: “pieces of silver”

- Line 28: “empty wine-skins”

“Journey of the Magi” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- Line 1: “cold coming”

- Line 4: “ways,” “deep,” “weather”

- Line 5: “dead,” “winter”

- Line 9: “summer,” “slopes”

- Line 10: “silken”

- Line 11: “camel,” “cursing”

- Line 12: “wanting,” “women”

- Line 18: “Sleeping,” “snatches”

- Line 19: “singing,” “saying”

- Line 20: “That this”

- Line 21: “dawn,” “down,” “valley”

- Line 22: “snow,” “smelling,” “vegetation”

- Line 27: “Six,” “door dicing,” “silver”

- Line 31: “say) satisfactory.”

- Line 35: “were we,” “way”

- Line 37: “doubt,” “death”

- Line 38: “But,” “different,” “Birth”

- Line 39: “bitter,” “Death,” “death”

- Line 42: “gods”

- Line 43: “glad”

- Lines 1-5: “'A cold coming we had of it, / Just the worst time of the year / For a journey, and such a long journey: / The ways deep and the weather sharp, / The very dead of winter.'”

- Lines 17-20: “At the end we preferred to travel all night, / Sleeping in snatches, / With the voices singing in our ears, saying / That this was all folly.”

- Line 4: “The,” “the weather”

- Line 5: “The very dead”

- Line 6: “And,” “camels,” “sore,” “refractory”

- Line 9: “The summer palaces,” “the terraces”

- Line 10: “the silken,” “bringing sherbet”

- Line 11: “Then,” “men,” “grumbling”

- Line 12: “running,” “liquor,” “women”

- Line 13: “n,” “ight-fires”

- Line 15: “high prices”

- Line 16: “time”

- Line 18: “Sleeping in”

- Line 19: “With,” “singing in,” “saying”

- Line 20: “this,” “all folly”

- Line 22: “below,” “snow,” “smelling,” “vegetation”

- Line 23: “stream,” “beating”

- Line 24: “three trees,” “low”

- Line 25: “And an,” “ old,” “meadow”

- Line 26: “vine”

- Line 27: “dicing”

- Line 28: “wine”

- Line 29: “no information,” “so”

- Line 30: “too soon”

- Line 31: “place,” “you,” “say”

- Line 41: “ease”

- Line 42: “people”

- Line 3: “journey, and”

- Line 6: “galled, sore-footed, refractory”

- Line 9: “slopes, the”

- Line 12: “away, and”

- Line 13: “out, and”

- Line 19: “ears, saying”

- Line 22: “Wet, below,” “line, smelling”

- Line 29: “information, and”

- Line 30: “evening, not”

- Line 31: “place; it”

- Line 32: “ago, I”

- Line 33: “again, but”

- Line 35: “This: were”

- Line 36: “Death? There”

- Line 37: “doubt. I”

- Line 38: “different; this”

- Line 39: “us, like Death, our”

- Line 40: “places, these”

- Line 41: “here, in”

- Line 2: “Just,” “ worst”

- Line 4: “ways deep,” “the weather sharp,”

- Line 7: “Lying down in,” “melting snow”

- Line 8: “There were,” “ times ,” “we regretted”

- Lines 9-10: “The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, / And the silken girls bringing sherbet.”

- Lines 11-12: “Then the camel men cursing and grumbling / and running away, and wanting their liquor and women,”

- Line 13: “night,” “-fires,” “out,” “shelters”

- Line 14: “cities hostile,” “towns”

- Line 15: “villages dirty ,” “high,” “ prices”

- Line 16: “hard,” “had”

- Line 17: “travel all”

- Line 18: “Sleeping in snatches”

- Line 19: “With the voices singing,” “our ears, saying”

- Line 20: “That this was all folly”

- Lines 21-25: “Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, / Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; / With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness, / And three trees on the low sky, / And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.”

- Line 32: “All,” “long”

- Lines 33-35: “set down / This set down / This”

- Line 35: “were we led all,” “way”

- Line 37: “evidence,” “doubt,” “death”

- Line 38: “different,” “Birth”

- Line 39: “Hard,” “bitter,” “Death,” “death”

- Line 42: “alien people,” “gods”

- Line 43: “glad,” “death”

Polysyndeton

- Line 11: “and”

- Line 12: “and,” “and,” “and”

- Line 13: “And,” “and”

- Line 14: “And,” “and”

- Line 15: “And,” “and”

- Line 23: “and”

- Line 24: “And”

- Line 25: “And”

- Line 3: “journey,” “journey”

- Line 36: “Birth or Death,” “Birth”

- Line 37: “ birth and death,”

- Line 38: “Birth”

- Line 39: “ Death, our death”

- Line 43: “death”

Rhetorical Question

- Lines 35-36: “were we led all that way for / Birth or Death?”

- Lines 4-5: “The ways deep and the weather sharp, / The very dead of winter.'”

- Lines 11-16: “Then the camel men cursing and grumbling / and running away, and wanting their liquor and women, / And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters, / And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly / And the villages dirty and charging high prices: / A hard time we had of it.”

- Line 22: “Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;”

- Lines 24-25: “And three trees on the low sky, / And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.”

“Journey of the Magi” Vocabulary

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- The Old Dispensation

- (Location in poem: )

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “Journey of the Magi”

Rhyme scheme, “journey of the magi” speaker, “journey of the magi” setting, literary and historical context of “journey of the magi”, more “journey of the magi” resources, external resources.

Eliot's Reading — The poem read by its author.

Lancelot Andrewes's Sermon — The 1622 Christmas sermon of the British bishop Lancelot Andrewes, which Eliot adapted for the poem's opening.

A Documentary on the Poet — A BBC production about Eliot's life and work.

Eliot and Christianity — An article exploring Eliot's relationship with his religion.

More Poems and Eliot's Biography — A valuable resource on Eliot's life and work from the Poetry Foundation.

LitCharts on Other Poems by T. S. Eliot

Four Quartets: Burnt Norton

La Figlia Che Piange

Morning at the Window

Portrait of a Lady

Rhapsody on a Windy Night

The Hollow Men

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

The Waste Land

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Find and share the perfect poems.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Journey of the Magi

Add to anthology.

‘A cold coming we had of it, Just the worst time of the year For a journey, and such a long journey: The ways deep and the weather sharp, The very dead of winter.’ And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory, Lying down in the melting snow. There were times we regretted The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, And the silken girls bringing sherbet. Then the camel men cursing and grumbling And running away, and wanting their liquor and women, And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters, And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly And the villages dirty and charging high prices: A hard time we had of it. At the end we preferred to travel all night, Sleeping in snatches, With the voices singing in our ears, saying That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness, And three trees on the low sky, And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow. Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel, Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver, And feet kicking the empty wine-skins, But there was no information, and so we continued And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember, And I would do it again, but set down This set down This: were we led all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly, We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death, But had thought they were different; this Birth was Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death. We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on December 24, 2023, by the Academy of American Poets.

More by this poet

The love song of j. alfred prufrock.

S’io credesse che mia risposta fosse A persona che mai tornasse al mondo, Questa fiamma staria senza piu scosse. Ma perciocche giammai di questo fondo Non torno vivo alcun, s’i’odo il vero, Senza tema d'infamia ti rispondo.

The Waste Land

“Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Σιβυλλα τι θελεις; respondebat illa: αποθανειν θελω.”

For Ezra Pound il miglior fabbro

I. The Burial of the Dead

The Naming of Cats

The Naming of Cats is a difficult matter, It isn’t just one of your holiday games; You may think at first I’m as mad as a hatter When I tell you, a cat must have THREE DIFFERENT NAMES. First of all, there’s the name that the family use daily, Such as Peter, Augustus, Alonzo, or James,

Snow-Bound [The sun that brief December day]

Christmas morn.

How sad, how glad, The Christmas morn! Some say, “To-day Dear Christ was born, And hope and mirth Flood all the earth; Who would be sad This Christmas morn.” How glad, how sad, The Christmas morn! “To-day,” some say Dear Christ was born, But oh! He died; Was crucified! Who could be glad This Christmas morn! Or glad, or sad, This Christmas morn, To some will come A joy new-born. The fleeting breath

From “The Dead”

Gabriel Conroy reflects on his wife’s former lover, Michael Furey.

The air of the room chilled his shoulders. He stretched himself cautiously along under the sheets and lay down beside his wife. One by one they were all becoming shades. Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age. He thought of how she who lay beside him had locked in her heart for so many years that image of her lover’s eyes when he had told her that he did not wish to live.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Journey of the Magi

By t.s. eliot, journey of the magi summary and analysis of journey of the magi.

The title of the poem refers to a “journey.” This word means an act of traveling from one place to another, but also, in a metaphorical sense, the long and often difficult process of personal change and development.

" Journey of the Magi " begins with a quotation from a Christmas sermon, which establishes the initial choral voice of the poem: the Persian kings who crossed the desert in winter to honor the birth of the baby Jesus. In the quotation, the magi, speaking in a plural "we," describe how the journey was difficult for them physically, emotionally, and spiritually. This quotation leads into a longer description of the difficulties of the journey.

The second stanza begins with a new dramatic beat: The dark night of the soul has passed, and it is now the dawn of a new day, literally and spiritually. The Magi descend into the fertile Judean valley. This stanza is full of Biblical allusions. The Magi find the manger where Jesus was born.

The third stanza switches to the voice of a singular Magus, who is reminiscing about the journey. (In retrospect, this could mean that the entire poem was written from a first-person perspective, but there was no way to know that before this point). He evaluates the experience, deciding that he “would do it again,” but then wonders at the paradox that the birth of Jesus was also a death. This death refers to both the death of Christ and the death of the old religious order, including the magical power of the Magus. He ends the poem wishing for another death, which represents both suicidal despair and an anticipation of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, ushering in a new Christian era.

The "journey" of the title describes the literal and mythic journey of the Magi across the desert to bring gifts to Jesus, the Christian messiah. It also describes the Magi’s internal journey from pagan to Christian. The Magus acts as a persona for Eliot, who went through his own conversion from agnostic to Anglican. From his point of view as a faithful Christian, the journey also represents the drastic change that the world undergoes at the birth of Jesus Christ.

The first five lines of the poem are in quotation marks. That’s because they are quoting the Nativity Sermon by Lancelot Andrewes, the Bishop of Winchester. He was a prominent clergyman and scholar who oversaw the translation of the King James Bible. The original text was from the Christmas sermon he preached to the Jacobean court in 1622: "A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solsitio brumali, the very dead of winter." Eliot wrote an essay titled “Lancelot Andrewes” (Selected Essays, 1934), in which he praised Andrewes’ leadership in the Church of England and harmonious blend of intellect and emotion.

The voice is a choral “we” of the three Magi who are recalling the journey to Bethlehem they undertook to witness the birth of Jesus. The Magi would have been crossing the desert from Persia to Judea. The Magi could not be quoting Lancelot Andrewes, because they would have made the journey in the first year of the Christian calendar—much before Andrewes lived. With the first “And,” the voice of the poem enters into the imaginative persona established by the sermon and builds upon it. So there is a poetic consciousness that is beyond the Magi, an anachronistic voice that is also on a Christian journey.

The journey is a hard one, especially for kings who are used to the luxurious life of “summer palaces” and “silken girls bringing sherbet.” They travel a long ways in wintertime through snow on the backs of uncooperative camels, with unhappy handlers. Both the Magi and their servants are going through withdrawals from a sensuous life of earthly comforts. They are cold and homeless and alien to the communities they pass through. In this way their journey parallels that of Mary and Joseph, who are famously denied a room at the inn, so Jesus is born in a manger. Spiritually, they are being tried, and stripped of everything familiar. They go through a dark night of the soul, literally and figuratively, with the voices of doubt discouraging them.

In the second stanza, the men enter a "temperate valley," and a shift occurs. The word “temperate” holds two meanings here: the valley is both mild and restrained. This is in contrast to the worlds described in the first stanza—both the precarious and decadent summer palaces, and the extremely cold winter in the desert. There is a supernatural and symbolic seasonal shift to spring: the valley is a fertile place, represented by water and the smell of vegetation. The running stream and water-mill also give movement to a landscape that was frozen in the last stanza. This is also a Biblical allusion: In John 4:10-14, Jesus called himself the Living Water. The stream powers a mill “beating the darkness,” alluding to Jesus’ claim in John 8:12 to be the Light of the World. The “three trees low on the sky” have been interpreted variously by scholars to refer to the crucifixion of Christ with the two thieves on crosses to either side of him, or the Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. This is an example of both symbolism and foreshadowing. The “white horse” refers to the one in Zechariah 6:5, who announces the coming of Jesus.

The Magi arrive at a tavern with “vine-leaves over the lintel,” a Biblical allusion to both the story of Passover from Exodus 12 and the notion of Christ as the “True Vine” (John 15:1, 5). The word “lintel” is rooted in the Latin word limen, which means threshold. They are on the threshold before both the entry to Bethlehem, and the moment before Christ is born, which for the Christian faithful will change the world entirely. The "hands" and "feet" in the next two lines are synecdoches, referring to people who are gambling and kicking wineskins to call for alcohol, by the parts of their bodies that are used in these debased actions. They are also biblical allusions to the bartering for Christ (Matthew 26:14-16) and Jesus’ parable of the new wine (Matthew 9:17). The faith of the Magi continues to be tested, as they receive no information, and “arrive not a moment too soon,” which could mean that they were at the end of their tether, or that they arrive just before or after Christ was born. Then there’s the peculiar phrase “Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.” This could be interpreted as the haughty, snarky view of kings looking down upon the stable in which Christ was born. But some scholars have also seen in it a reference to Article 31 of the Anglican Articles, in which Christ's sacrifice "satisfies" the debt of all mankind’s sins.

The first line of the final stanza situates it at a later time than the other two stanzas. It frames the text as a story within a story, and makes the speaker’s tale less reliable, as it is a memory of a long-ago event. The speaker has shifted to a singular “I” who is evaluating the journey after it has past. He decides that he “would do it again,” but that’s not his final thought—there’s a comma and a “but,” a qualifier, and then the urgent plea, repeated twice, to “set down this,” which means write this down. The lines “but set down/ This set down/ This” come from speech patterns that Andrewes used in his Nativity sermons of 1616, 1622, and 1623. Then we get to the question that’s critically important to the Magus: “were we led all that way for/Birth or Death?”

He starts to think through the answer to his question with “There was a Birth, certainly, We had evidence and no doubt.” This is a rational critical consciousness, assessing the historical fact of Jesus’ birth. He relates this to his past experience with birth and death, and says that he “had thought they were different.” Indeed, birth and death are usually figured as opposites. So, we are entering the realm of paradox here, as he relays his emotional experience of Christ’s birth: “this Birth was/Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.” This experience has changed his view of the fundamental meaning of life and death, and made them synonymous. It reflects the painful paradox at the heart of Christianity: Christ was born to die.

Notice the capitalizations of Birth and Death in these lines: this is granting a deference to Christ that conveys the Magus’ and the poet’s faith. The second “death” in this line is not capitalized, as it refers to the Magi’s death. This is significant because it sets up a contrast: Christ’s “Death” is more important than the Magi’s “death.” This must refer to a metaphoric death, since the Magus speaks while he is still living. (Indeed, it is a simile). In imagining how the birth and death of Christ relates to the metaphoric death of the Magi, it’s significant to note that the word Magi also meant Sorcerers; the word comes from the same root as magic. So the birth of Christianity is also the death of the old ways of Magicians. The Magi lost their magic, their power, their relevance, and experienced a type of social death.

The Magus then returns to his story, to tell a coda of the return to their kingdoms. Remember, these were the sensual palaces they left behind to make the journey. But he has changed, and is “no longer at ease.” In Christian theology, “dispensation” means a divinely ordained system prevailing at a particular period of history. The phrase “the old dispensation” means that the divine system, the meaning of life, has changed. He then finds his own people to be “alien” as they “clutch” false idols.

The Magus is existentially exhausted and ultimately suicidal, as he ends with “I should be glad of another death”—meaning his own. In this deeply anticlimactic ending, the poem imagines the advent of Christianity as a calamity for the old world. He may also wish for death because he no longer has use for earthly pleasures, and looks forward to the kingdom of heaven. Another possible interpretation of the last line is that the Magus is speaking during the time period when Christ has been born, but has not yet died. The Magus would then be wishing for Christ’s death, and thus for his resurrection and the salvation of mankind. It's important to notice that these two possible meanings of the last line of “Journey of the Magi” are not mutually exclusive: the context of the poem is the point of view of someone with a new faith that makes his old position and world obsolete. He is waiting for his own death, along with the death and of Christ, who will be born again to redeem the world and usher in a new dispensation, a world in which the Magi themselves have no place.

Journey of the Magi Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Journey of the Magi is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

The journey of the magi

In the first two stanzas of the poem, the speaker is a choral “we” of the three Magi recalling the journey to Bethlehem they undertook to witness the birth of Jesus. In the final stanza the voice shifts to the singular “I” of a Magus who evaluates...

Discuss the theme of the life is a journey

What are the characteristics of the Magi in the poem?

The Magi are determined, unsure, and in the end transformed.

Study Guide for Journey of the Magi

Journey of the Magi study guide contains a biography of T.S. Eliot, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Journey of the Magi

- Journey of the Magi Summary

- Character List

Essays for Journey of the Magi

Journey of the Magi essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Journey of the Magi by T.S. Eliot.

- The Importance of Ambiguity in the Representation of Reality and Truth in "Preludes," "The Hollow Men," and "Journey of the Magi"

- Children’s Poetry Archive

- Poetry Archive Now

- Collections

- Keystone Collections

- The Mighty Dead

- Become a Member

- Archive Insider

- Poetry Champions

- A gift in your will

- American donors

- Our supporters

- Poetry Catalogue

- My Downloads

- My Dedications

Listen to the world’s best poetry read out loud.

Journey of the magi.

by T. S. Eliot

Journey of the Magi - T. S. Eliot

I think this is the first time I've ever read any of my own poems over the radio for either an American or an English audience, though I've done so once or twice for overseas services...I shall now take one of my 'Ariel' poems. 'Ariel Poems' was the title of a series of poems which included many other poets as well as myself. These were all new poems which were published during four or five successive years as a kind of Christmas card. Nobody else seemed to want the title afterward so I kept it for myself, simply to designate four of my poems which appeared in this way. 'Journey of the Magi' is obviously a subject suitable for the Christmas season.

‘A cold coming we had of it, Just the worst time of the year For a journey, and such a long journey: The ways deep and the weather sharp, The very dead of winter.’ And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory, Lying down in the melting snow. There were times we regretted The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, And the silken girls bringing sherbet. Then the camel men cursing and grumbling And running away, and wanting their liquor and women, And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters, And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly And the villages dirty and charging high prices: A hard time we had of it. At the end we preferred to travel all night, Sleeping in snatches, With the voices singing in our ears, saying That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness, And three trees on the low sky, And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow. Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel, Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver, And feet kicking the empty wine-skins, But there was no information, and so we continued And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember, And I would do it again, but set down This set down This: were we led all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly, We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death, But had thought they were different; this Birth was Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death. We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.

Journey of the Magi is from Collected Poems 1909-1962 (Faber, 1974), by permission of the publisher, Faber & Faber Ltd and kind support of The T S Eliot Foundation. Recording by permission of the BBC. Find the T S Eliot Foundation here: https://tseliot.com/ Find our T S Eliot Prize Winners’ Collection, supported by the T S Eliot Foundation, here: https://poetryarchive.org/collections/t-s-eliot-prize/

The free tracks you can enjoy in the Poetry Archive are a selection of a poet’s work. Our catalogue store includes many more recordings which you can download to your device.

T. S. Eliot

Explore similar poems, also by t. s. eliot, the waste land part i – the burial of the dead, the waste land part ii – a game of chess, the waste land part iii – the fire sermon, the waste land part iv – death by water, the waste land part v – what the thunder said, four quartets – extract, by similar tags, poetry archive now wordview 2023: sono, poetry archive now wordview 2023: one thing i know about healing, poetry archive now wordview 2023: when they bombed, the girls at st catherine’s.

by Paul Groves

The Four Corners of the Circle

Brain drain, featured in the archive, special collection, national memory day, guided tour, dr rowan williams: guided tour.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Lost your password?

A Short Analysis of T. S. Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi’

A critical reading of a classic Christmas poem – analysed by Dr Oliver Tearle

‘Journey of the Magi’ by T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) was the first of a series of poems written by the poet for his employer, the publisher Faber and Faber, composed for special booklets or greetings cards which were issued in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Eliot claimed he wrote ‘Journey of the Magi’ in 1927, on a single day, one Sunday after church.

You can read the poem here . Below we offer some notes towards an analysis of this difficult and elusive poem, with particular focus on its meaning and imagery.

‘Journey of the Magi’: background context

‘Journey of the Magi’ is told from the perspective of one of the Magi (commonly known as the ‘Three Wise Men’, though the Bible makes no mention of their number or gender) visiting the infant Christ. The poem examines the implications that the advent of Christ had for the other religions of the time, chiefly the Zoroastrianism of the Magi themselves.

Eliot converted to Christianity in 1927 , the same year he wrote ‘Journey of the Magi’, so this is an apt poem for him to have written shortly after his acceptance into the Church of England.

According to Eliot’s second wife, Valerie, he wrote the poem very quickly: ‘I had been thinking about it in church,’ he told her years later, ‘and when I got home I opened a half-bottle of Booth’s Gin, poured myself a drink, and began to write. By lunchtime, the poem, and the half-bottle of gin, were both finished.’

The title of the poem is significant, not least Eliot’s use of the word ‘Magi’: think about its very foreignness and its ambiguity (the term originally denoted Persian Zoroastrian priests, but had come to carry the more general meaning of ‘astrologers’ – or, if you like, magicians).

This foreign and alien quality is obviously related to what the poem is about: namely, one group of people becoming alienated by the coming of another group, the people who will, in time, follow the new religion of Christianity which will lead to the death of the religions the Magi, or astrologers, follow.

The Magi are like the ‘hollow men’ of Eliot’s poem of that title from two years before: together, they find they are alienated from the rest of the world, in some sort of between-existence or limbo (because the world is in a transition between their old Zoroastrian faith and the new, emerging faith of Christianity which will supersede it).

‘Journey of the Magi’: summary

The speaker, one of the Magi, talks about the difficulties encountered by the Magi during the course of their journey to see the infant Christ.

It is unconventional to focus on the details of the journey: their longing for home (and for the ‘silken girls’ bringing the sweet drink known as ‘sherbet’), their doubts about the point of the journey they’re undertaking, the unfriendly people in the villages where they stop over for the night, and so on.

Eventually, the Magi arrive at the place where the infant Christ is to be found. The poem ends with the poem’s speaker reflecting on the journey years later, saying that if he had the chance he would do it again, but he would add that we remains unsure about the precise significance of the journey and what they found when they arrived.

Was it the birth of a new world (Christianity) or the death of an old one (i.e. the Magi’s own world)? The speaker then reveals that, since he returned home following his visit to see the infant Christ, he and his peers have felt uneasy living among his people, who now seem to be ‘an alien people clutching their gods’ (in contrast to the worshippers of the newly arrived Jesus, who worship one god only, in the form of the Messiah).

The speaker ends by telling us that he is resigned to die now, glad of ‘another death’ (his own) to complement the death of his cultural and religious beliefs, which have been destroyed by his witnessing the baby Jesus.

‘Journey of the Magi’: analysis

There are several things which are odd about Eliot’s poem.

First, for a poem titled ‘Journey of the Magi’, there is no mention of the star which – the Gospels and a million children’s nativity plays tell us – guided the Magi to the spot where Christ lay in a manger.

Second, the actual nativity scene itself is elided from the narrative: the Magi travel to the place where Christ is to be found, locate it, and then suddenly the speaker of the poem is looking back on the journey years later as an old man.

Jesus himself is absent from the poem. Is this because this part of the story is familiar to us, but the Magi themselves are not – or specifically, how the Magi would have felt about seeing their deeply-held beliefs cast into doubt by this new Messiah? Yet surely one way to convince us of the impact of this new-born deity on the lives of these Persian astrologers would have been to show us how they reacted when faced with the baby Christ.

There are several possible reasons why Eliot would have chosen to leave Jesus out of the poem, but they all raise additional questions.

Note also how the imagery foreshadows Christ’s later life and crucifixion: the three trees suggesting Christ’s crucifixion, between two thieves on the mountain; the vine, to which Jesus will liken himself; the pieces of silver foreshadowing the thirty pieces of silver Judas Iscariot will receive for betraying him; the wine-skins foreshadowing the wine that Jesus would beseech his disciples to drink in memory of him at the Last Supper.

These details are significant not least because the speaker is a priest or astrologer, someone who is trained to look for significance in the things around him, to read and interpret signs as symbols or omens. But he fails to pick up on what they foreshadow; we, however, living in a Christian (or even a post-Christian) society, can read their significance. At the end, the speaker is left feeling jaded and lost by the advent of Christ: he wonders whether Christ’s birth has been a good thing, since his arrival in the world signalled the death of his religion and the religion of his people. Now, he and his fellow Magi are world-weary and welcome the end.

‘Journey of the Magi’ is partly about belonging, about social, tribal, and religious belonging: the speaker of the poem reflects sadly that the coming of Christ has rendered his own gods and his own tribe effete, displaced, destined to be overtaken by the advent of Christ – and, with him, Christianity.

It is tempting to see the poem – written in the year Eliot converted to Anglo-Catholicism – as a metaphor for Eliot’s own feelings concerning secularism and the Christian religion, Christianity having itself been rendered effete in the face of Darwin, modern physics, and secular philosophy. The poem, about a people’s conversion from one religion to another, is equally bound up with Eliot’s own conversion.

However, a more nuanced reading invites us to see the poem as an account of the ways in which every religious and ethnic identity is in some sense threatened, at some time or in some place, by other, more dominant groups and identities. A possible allusion to Othello’s ‘Set you down this’ (his dying words in Shakespeare’s play) points up the religious and ethnic differences which underlie the poem’s setting: Othello, like Eliot, had converted to Christianity, since he was a Muslim moor who converted when he joined the Christian world of Venice.

(It should be noted, though, that there is an alternative source for these lines in Eliot’s poem: in one of his sermons, Lancelot Andrewes writes, ‘Secondly, set down this’. As with many allusions in Eliot’s poetry, there are several possible sources which Eliot may be calling into play.)

The poem, then, is not just about religious identity but about broader issues of ethnic and cultural identity, too. Note how the poem doesn’t mention Christ’s name anywhere, or that the infant they are travelling to see is Jesus: it doesn’t need to be said. Then recall the foreignness of ‘Magi’ in that title.

The Magi are already ‘other’, the alien ones or outsiders: when the speaker tells us at the end that they returned to ‘our places, these Kingdoms’, it is tempting to see the poem as in some sense a development of ‘The Hollow Men’, which was also about a group of men feeling lost and empty in a ‘kingdom’ where they appear to long for death.

It is undoubtedly this multifaceted quality to the poem which helped it to become one of the nation’s favourite poems in 1996 (it was no. 44 on the list – one higher than the childhood favourite by Edward Lear, ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’ ).

‘Journey of the Magi’ is a more accessible poem than some of T. S. Eliot’s other work, yet it remains a challenging piece of poetry in many ways. It is only through analysing some of its images and more curious details that we can begin to appreciate it at a deeper level.

Continue to explore Eliot’s poetry with our analysis of his great religious poem, Ash-Wednesday , our introduction to his suite of religious poems Four Quartets , and our discussion of his early modernist masterpiece, ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ .

Image: Journey of the Magi, mosaic, Basilica Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, ca. 6th c. , Wikimedia Commons.

11 thoughts on “A Short Analysis of T. S. Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi’”

What a fabulous analysis of one of my favourite poems. I always read it with a lump in my throat… the sense of despair at having outlived his sense of rightness about his own culture and religion always seems desperately sad to me. Thank you, also, for teasing out some of the more problematical aspects of this nuanced and layered poem:).

Thank you – very glad you found the analysis useful and of interest. The most poignant part for me has to be the speaker’s failure to see the significance of those symbols which foreshadow Jesus’ later life. He’s spent his whole life interpreting signs, and yet these point to a future which he will never know. A terrific poem :)

Yes! You’re right – and that aspect of the poem had never occurred to me before… which, as you say, just adds to the sense of sadness.

I had an LP of Modern Poets and this was one featured – possibly with John Gielgud reading it!

I bet it sounded wonderful, it is a lovely poem to read aloud…

Reblogged this on Manolis .

- Pingback: 10 Great Christmas Poems | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Sunday Post – 18th December 2016 | Brainfluff

- Pingback: 10 Great Winter Poems Everyone Should Read | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: 10 T. S. Eliot Poems Everyone Should Read | Interesting Literature

Surely the lack of reference to Christ’s birth, the star etc (what you call elision) is due to the fact that Eliot wants to concentrate not on the event (which we should all know about, or can find out about) but on its effect on the Magi? I assume that’s why the title is “The journey (i.e. inner) of the Magi”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

<script id=”mcjs”>!function(c,h,i,m,p){m=c.createElement(h),p=c.getElementsByTagName(h)[0],m.async=1,m.src=i,p.parentNode.insertBefore(m,p)}(document,”script”,”https://chimpstatic.com/mcjs-connected/js/users/af4361760bc02ab0eff6e60b8/c34d55e4130dd898cc3b7c759.js”);</script>

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi

Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 4, 2020 • ( 0 )

This poem (1927), the first of Eliot’s contributions to the Ariel series, is, along with “A Song for Simeon,” certainly far easier to place within the immediate context of the Christmas season that inspires it than his later contributions might seem to be. Eliot’s title would quickly make anyone with even the most general and secular awareness of the popular associations connected with Christmas mindful of the three wise men, or magi. Celebrated in song and image, they constitute an integral part of the lore of the Christmas story to this day. The three magi, history would have it, were pagan priests from the East, most likely adepts in astrology from the environs of Persia, who, on the basis of their observations of the stars, traveled westward, guided by the so-called Star of Bethlehem, to the “place where Jesus lay.” Tradition would further have it that they had become convinced by the astrological charts that they had cast that a great king was about to be born, one whose birth, life, and death would usher in a new age.

The Journey of the Magi, Illustrated Vita Christi, c.1190-1200

In his poem, Eliot focuses on the trials of the magi’s journey to the stable in Bethlehem and on the hope that they placed in the miraculous birth that they had traveled so far to witness, as well as on the effect that witnessing such an event had subsequently had on them. Rather than telling their story, however, Eliot, in keeping with his use of the dramatic mask that goes back as far at least as to characterizations such as J. Alfred Prufrock, imagines himself to be one of the magi many years later, telling his story apparently to a scribe so that there will be preserved a written record of it. It is a clever literary device, one that such prominent 19th-century poets as Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning had already used to great advantage. By pretending to be great literary or historical figures such as the Greek hero Ulysses or the Renaissance painter Andrea del Sarto in dramatic monologues that sought to reveal the psychology of character as much as the ruminations of theme, they were able to explore a wider range of human experience than any lyric poet can typically undergo in a lifetime and yet still use that most powerful rhetorical device, the authority of the first-person singular voice, the “I” of firsthand experience and eyewitness accounts. Utilizing the opportunities for modulating voice and poetic mask through the medium of these dramatic monologues to which those two poets had thereby reintroduced literary audiences, Eliot’s contemporary poet and good friend, the fellow American expatriate Ezra Pound, had earlier done something similar to what Eliot does with the magi with another biblical character in “The Ballad of the Goodly Fere” (1909). In that poem, the imagined speaker, Simon the Zealot, is permitted to “come to life,” as it were, to give a first-person account of Christ’s Crucifixion.

In every case, the aim of the poet using this form is to make the tired but true sound refreshingly new by giving it the characteristics of living speech caught as if in the act of being spoken. In Pound’s poem, for example, despite the artificial note struck by the pronounced rhythm and rhyme scheme required of the traditional ballad form, Simon speaks in something of a Cockney accent, making him sound like a contemporary working-class bloke rather than a high-toned Christian preacher.

The dramatic monologue was hardly a new device in Eliot’s poetic repertoire, of course. He had already expanded that form’s potential in such works as “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” “Gerontion,” and “The Hollow Men,” to name several outstanding examples, not to mention The Waste Land , in which he set new and perhaps permanent standards for the manipulation of persona and voice as a mode of poetic discourse. But somewhat like Tennyson, whose dramatic monologues can strike readers as elaborate contrivances for all their poetic power, Eliot tended to make the form more of a poetic than a purely dramatic exercise. Prufrock might sound as if he is speaking his thoughts and feelings, for example, but they are freely combined with purely literary elements, and the entire mix is then mangled into the fragmentary by his emotional ups and downs so that any resemblance to recorded speech is purposefully blurred if not obliterated.

In the Ariel poems in general and in “Journey of the Magi” in particular, Eliot exceeds the models of those two other masters of the form and accomplishes a poetry closer in its perfection as a dramatic monologue to the considerable achievements of Robert Browning. He does so in the powerful sense of audience that he creates. The reader is made witness—only an auditory one, it is true, but a real one nevertheless—to one of the magi as he, ruminating here, reflecting there, now regretting, now rejoicing, bears witness to the events of that momentous journey, all for the sake of the invisible and silent scribe.

Note, for example, that although no specific passage of time since the journey has taken place is mentioned, it is not difficult to catch in the speaker’s tone the sense that quite some time has passed since that eventful winter’s night when they came upon the scene in Bethlehem. This is not a man still caught up in the excitement, confusions, and exhaustion of the moment, nor is he someone who has just recently returned home from an arduous trip who is sharing both his thoughts on what it was like and his relief that it is now over. Rather there is a weariness concealed in his account, a measure of helpless disappointment akin somewhat, perhaps, to the overall fatigue that invades the musings of the old man/speaker of “Gerontion.”

And yet there is a tone of self-importance as well, a sort of “I was there, let me tell you” puffery, as if Eliot wishes to leave the impression, which is always aesthetically more effective than any direct treatment of setting or subject matter, that this is an I-knew-him-when sort of summation that the speaker is making, coming long after the baby he sought on that long ago journey had matured into not the king that they had imagined that they would 276 “Journey of the Magi” find but the sacrificial victim whose birth, life, and death had nevertheless redeemed and transformed human history in ways that no one, not even these fabled wise men, could ever have anticipated. The dramatic monologue is the perfect instrument for creating ironic tensions between what the fictional speaker thinks he is saying and what the poet wants his own readers to hear. Surely, Eliot’s magus is, these many years later, less impressed with the event and more full of himself than someone who had come that close to miracle has any right to be, and to a great measure, that is the effect that Eliot is aiming to achieve.

Even now, child of the old dispensation that he self-confessedly is, Eliot’s speaker can only muse on the event with a vague appreciation for but even vaguer understanding of the changes that that birth have subsequently wrought upon him and his world. The magus begins his recollection by recalling the coldness of the journey, and to give that recollection its antique quality as if it comes not just from an earlier time but from another age, Eliot quotes virtually verbatim (and even uses quotation marks as if to underscore this point) the 300-year-old words of the 17th-century English cleric Sir Lancelot Andrewes, a contemporary and fellow word stylist of the metaphysical poet JOHN DONNE. In the passage from the Andrewes sermon that Eliot employs to set the scene and tone for his own speaker’s account, Andrewes comments on the Nativity and on how awful it was for Joseph and Mary to undertake the journey to Bethlehem. “A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey in,” he commences. The only real alteration that Eliot makes in Andrewes’s original prose, indeed, is to change a third-person plural verb, they, to the first person plural, we, in keeping with the fiction that his own poem is a first-person telling of the episode.

For those who might recognize Eliot’s original source, it is as if the presence of the holy family has infiltrated the text to begin with, lurking in the corners of the reader’s own experience of the poem as it continues. This is, after all, a poem focusing on the paradoxical contrasts that the birth of Christ and his life’s mission will force on the religious imagination that will emerge from Christianity. The light of the world comes at the darkest time of the year. The king of the world is born amid conditions associated with the most abject poverty. The fire of God’s love comes at a time of bitter cold. Eliot allows the speaker’s remembrances to reflect these sharp contrasts, as he thinks of the summery life that he had left behind to make the journey, with its “summer palaces on slopes” and “silken girls bringing sherbet,” whereas all about them now, instead, is a barren winter landscape, inhabited by uncouth ruffians, an inhospitable and alien environment that seems to mock them with the nagging feeling that the perilous journey that they have undertaken is little more than “all folly.”

Having painted such a bleak scene of doubt and desperation, the speaker thus manages to surprise the reader all the more with the sudden burst of vitality with which the second stanza opens. As if it is resplendent of the hope for new life that is itself embodied in Christ, the speaker reports that they reached “at dawn . . . a temperate valley, / . . . smelling of vegetation.” This scene provides what Eliot would call an objective correlative for the spark of a rebirth, allowing Eliot to share with his contemporary readers a glimpse of the potential contained in this particular birth that his speaker could not even begin to imagine, the Earth’s resurrection into grace that Christ’s own birth foreshadows for the human spirit. However, as if to emphasize that the journey from this miraculous moment to the final redemption of humankind is a far longer and more arduous journey than any that the magi may ever have undertaken, as well as one more fraught with the defects of human folly than theirs, the dark of winter encroaches again in a flood of foreshadowing images and blots out that refreshing scene with which the second stanza had opened in its momentary flash of new life and, with it, hope.

If the sought-for birth truly were daybreak for a new epoch of humanity, then upon that still fragile hope, at this moment nothing more than a newborn infant, the darkness of this world drops again, as W. B. Yeats would put it, in the image of “three trees on the low sky.” They cast the long shadow of Christ’s death on a cross, a thief crucified to each side, backward over the pastoral valley of his birth, thus hardly permitting the speaker, or the reader, so much as a moment’s respite from the fact that heaven has not yet arrived on Earth, only its king. While it is clear that the speaker could not recognize the special significance of this and other details that follow the description of the pleasant valley setting, these images of the coming catastrophe of Christ’s Crucifixion muddy the scene and darken even the relatively ignorant speaker’s mood and tone. Eliot is also still employing the dramatic irony that he had used earlier; the poem is addressed to a contemporary Christian audience, after all, one that would definitely get the message that the first Christmas will end in the Passion of the Christ.

In the poem, at least, the darkness does not lift. Employing techniques similar to contemporary films, in which a juxtaposed image comments on a scene but is not otherwise related to it in content, Eliot now allows a horse to careen across the landscape, suggesting a natural universe out of control and hovering on the edge of chaos, and then there is a tavern and men playing dice for silver, bringing to mind the boisterous, drunken Roman soldiers who would later gamble for Christ’s garments at the foot of the cross, and Judas, too, who betrayed him for 30 pieces of silver. The speaker continues his memoir, totally unaware of the tragedy that he is seeing foretold, and concludes, pedantically, that they finally arrived at their destination, “[f]inding the place . . . (you may say) satisfactory.”

CRITICAL COMMENTARY

The understatement at first astounds and then renders itself perfectly understandable. For all of their acquaintance with mystery, its human dimensions, Eliot offers the suggestion that the magi could not possibly have understood the profundities of the unfolding mystery that they were there to witness in its initial manifestation. But then Eliot has his speaker surprise the reader by expressing at least the inkling of some awareness that, even when counted among miraculous things, this was no ordinary birth and that something far more than merely extraordinary had entered the world and, through it, human history. The speaker seems to know, or at the very least intuit, that his age and his kind, and all the wisdom of his world, is coming to an end and that this birth is the signal of their death. “[W]ere we led all that way for / Birth or Death?” he wonders, entertaining the paradox of the contradictions that such a blessing portends. Such a birth brings with it renewal, but renewal requires the removal of all those things that are now to be replaced. His is “the old dispensation,” a world that for the speaker still exists but that for Eliot and his readers is by now something even less than a relic—all that which was born too soon and died too early.

The speaker confesses that his long-ago experience has forever unsettled his life; he is “no longer at ease here” in his familiar surroundings, but to what purpose he neither puzzles out nor supposes. Like Eliot’s hollow men, he appears to have seen the light but is unable either to recognize its source or to follow it, so he shall die in the wilderness that, for Eliot, is a world without a coherent belief in a singular creation that serves a singular purpose. For all his wisdom, the speaker’s tragedy is to have come that close to mystery and majesty without having grasped its significance for him and him alone, a state of affairs whose continuing implications could not have been lost on a contemporary reader, Eliot among them.

Christ said to Nicodemus that to be saved he must be reborn, and Eliot closes the poem by seeming to play on this cryptic injunction. “I should be glad of another death,” the speaker says in an ironic twist on the notion of a spiritual rebirth, as if for him sharing the common lot of the grave would have been a better fate than to have been fated to glimpse those many years before in that desert birth the unsettling truth that his age was coming to an end along with all else that he and his hold dear—as if, for him, to gain some inkling that there is something better and greater can be worse than to know nothing at all. Eliot’s speaker seems to share the plea of the speaker in Matthew Arnold’s “Stanzas from the Grand Chartreuse” (1854), who begs the harbingers of a new age that he, the speaker, knows he will not live to see to “leave our desert to its peace.”

The allusion to Othello’s closing speech in Shakespeare’s great tragedy that comes when Eliot’s speaker commands the scribe to “set down / This” has been often noted, but what Eliot has to say of that moment in the play Othello may cast some further light on what the reader ought to make of the speaker of the Eliot poem. When, just before stabbing himself to death, Othello defends himself by recalling the services that he has done Venice and makes a similar command, “Set you down this,” to the Venetians who stand about him, thunderstruck at the terrible deeds of death and violence that they have just witnessed, Eliot, in his essay “Shakespeare and the Stoicism of Seneca,” which was also published in 1927, writes that Othello “in making this speech is cheering himself up . . . [by] dramatizing himself rather than his environment.” In the same manner, Eliot’s magus sees this unfolding drama, whose initial moment he was privileged to witness, only in terms of its effects on him—the sort of self-centeredness that the Christian ethic encourages humanity to abhor. As Eliot would summarize this defect later in his poem “The Dry Salvages,” one might say of the speaker of “Journey of the Magi” that he “had the experience but missed the meaning.”

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Journey of the Magi , Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Bibliography of Journey of the Magi , Bibliography of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Character Study of Journey of the Magi , Character Study of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Criticism of Journey of the Magi , Criticism of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , eliot , Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Essays of Journey of the Magi , Essays of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Journey of the Magi , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Modernism , Notes of Journey of the Magi , Notes of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Plot of Journey of the Magi , Plot of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Poetry , Simple Analysis of Journey of the Magi , Simple Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Study Guides of Journey of the Magi , Study Guides of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Summary of Journey of the Magi , Summary of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , Synopsis of Journey of the Magi , Synopsis of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi , T. S. Eliot , Themes of Journey of the Magi , Themes of T.S. Eliot’s Journey of the Magi

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Journey of the Magi Introduction

In a nutshell.

Merry Christmas! It's a birth-of-Jesus poem!

Er, almost…

"Journey of the Magi," though often thought of as minor in T.S. Eliot 's overall oeuvre (a fancy French term that basically means "everything the guy's ever done"), is nevertheless cited by academics as a piece that signifies a major transformation in the poet's career. And it should be—it was composed right around the time that Eliot converted from Unitarianism to Anglicanism, in 1927. Not to go into too much religious detail right here and now, but let's just say that the switch was from "not really very religious at all" to "pretty devout, actually." It was kind of a big deal.

So "Journey of the Magi," then, often gets scrutinized for containing bits and pieces of Eliot's feelings about said conversion, even though the poem itself isn't (on the surface, anyway) about Eliot at all. Instead, the piece details the thoughts of one particular Magus (that's the singular version of Magi)—one of the Three Wise Men. You know, the dudes bringing frankincense, gold, and myrrh to the newborn Jesus? Right—those guys.

This poem takes place just a smidge before the wise men get to the stable. It details the hardships of the journey, the skepticism of the Magus (seems like they left that part out of the Bible), and the landscape of Bethlehem. In the end, the narrator is shaken to his very core by what he sees, because change, it is a-comin', and change can be scary business.

You might be able to see, then, where people get this whole idea that the narrative is also, subtext-wise, about Eliot's own conversion (a word that means change). After "Journey," which was published in 1930, Eliot didn't write a whole lot else—or rather, not a whole lot that we get particularly excited about. His gigantic works of literature—namely, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" and "The Waste Land" —had already been published, and had put T.S. Eliot on the map as one of the greatest poetic minds of his time. But this poem, as we'll see in a minute, is much more than just a Christmas poem. Even though the story at first seems simple, the piece teems with intricate symbols , obscure references , and layers of subtext. Sudden religiosity or no, this is still very recognizably T.S. Eliot.

Why Should I Care?

For one thing, it's always kind of neat to see traditional stories played with a bit—especially by authors who are the best of their kind at such playing. The Bible doesn't get into the wise men's heads, really, and so "Journey of the Magi" fills in a gap, which is always cool. But what if we don't really know the Bible? Or its stories? What if we're not Christian? What could this poem possibly have to tell us?

A lot, as it turns out. If we move for a minute past the Biblical nature of this poem, what the thing's really about is change . And we've all had to deal with that. Moving to a new town. First day of high school. Puberty. Any kind of spiritual revelation, Christian or otherwise. Going to college. You get the picture. All of these things are turning points in our lives, and you know what? They can be terrifying . Even if they turn out to be pretty awesome in the end (college, for instance, is just the best, once you're done hyperventilating about it).

This happens to be the case for the Magus in this poem. If you're familiar with the traditional Biblical story, you know that the Magi saw an angel that proclaimed to them some seriously Good News: that a savior was going to be born in Bethlehem. We're talking here about a person who was going to bring the kind of peace and prosperity to the world the likes of which the world had never seen . Couldn't be a bad thing, right? Right.

Except for the fact that well, hmm, what is this change going to look like ? Maybe it'll be stressful, maybe it'll throw some Kings (which is what the Magi were) out of power. We're betting at least one of them was going, "Hmm, I dunno about all this…"

See where we're going? Even in the face of something that's supposed to be the best thing ever , there's fear and uncertainty and doubt. It's what we all grapple with when we're trying to deal with major change, too. Eliot's poem is just one really unique way to tell us about one man's trouble with transition, and to help us see that even seemingly doubt-free things like religious conversion can be way more complicated than they first appear.

Tired of ads?

Cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

Journey of the Magi

21 pages • 42 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Poem Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Further Reading & Resources

Discussion Questions

Authorial Context

At the time he published “Journey of the Magi,” Eliot was known primarily for his exploration in poetry of the decay of Western culture. He was most famous for “The Waste Land,” a poem in which people live their everyday lives without purpose or belief. Society is fragmented and sterile, without any underlying common values to support it. “The Hollow Men” (1925), as its title suggests, expresses a similar point of view . The hollow men are the spiritually dead, living ghostly, ineffective lives:

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar (T. S. Eliot. “ The Hollow Men .” All Poetry. 1925. Lines 5-10).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,450+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By T. S. Eliot

Ash Wednesday

T. S. Eliot

Four Quartets

Little Gidding

Mr. Mistoffelees

Murder in the Cathedral

Portrait of a Lady

Rhapsody On A Windy Night

The Cocktail Party

The Hollow Men

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

The Song of the Jellicles

The Waste Land

Tradition and the Individual Talent

Featured Collections

Allegories of Modern Life

View Collection

Christian Literature

Nobel Laureates in Literature

Religion & Spirituality

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

The Journey of the Magi

Three wise men, guided by a star, search for the new-born Christ.

According to St Matthew’s Gospel: ‘Wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, “Where is he who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen His star in the East and have come to worship Him”.’

The three wise men who sought the infant Christ represented the entire world: Melchior, the eldest; Balthazar, traditionally portrayed as black; and Gaspar (or Caspar), the youngest. But in Benozzo Gozzoli’s portrayal of them, depicted in frescoes on three walls of the chapel of the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the world is reduced to the Florence of the Medici family and its clients.

Here, from the east wall, at centre right, astride a white horse, is Gaspar, an idealised portrayal of the young Lorenzo, who would attain the title ‘Magnificent’. Mounted behind him are his father, Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici, ‘the Gouty’; and, on a donkey in imitation of Christ, Cosimo de’ Medici, the patriarch of the family that dominated the Tuscan city at the heart of the Renaissance.

The fresco was commissioned by Piero for the palazzo’s chapel, permission for which had been granted by Pope Martin V in 1442. The chapel was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, which had been the subject of a Church Council held in Florence in 1439. It established the Trinitarian principle that: ‘The Holy Ghost has his nature and subsistence at once from the Father and the Son.’

Gozzoli had returned to Florence from Rome in the 1450s and the Medici, ludicrously rich, employed him at great expense and at some speed to fashion frescoes similar in design to the tapestries that had become all the rage. Jewels and pure gold leaf added extraordinary colour to his creation.

There is none of T.S. Eliot’s ‘cold coming’, described in his poem ‘Journey of the Magi’ (1927), but a sumptuous, secular procession, with a deer hunt in the background and, at the top of the composition, Jerusalem in the shape of the Medici’s country villa at Cafaggiolo. Gozzoli, in a self-portrait, gazes at the viewer from second row, third from left.

Related Articles

A Grecian Harvest Home

Augustus Closes the Temple of Janus

Popular articles.

Columbine 25 Years On

Challenging the ‘Ugliness’ of Anne of Cleves

The story behind T.S. Eliot’s magnificent “Journey of the Magi”

Renata Sedmakova | Shutterstock

Around this time of year, my mind always turns to T.S. Eliot’s magnificent Christmas poem, “ The Journey of the Magi .”

He begins it by alluding to how the holiday finds us huddled inside the comfort of our homes, stockings hung by the fire, hot chocolate in hand, tucked away from the dark and cold. The Magi, however, are on their long journey to the side of Christ, so they’re outside in the winter frost, footsore and exposed to the elements:

A cold coming we had of it, Just the worst time of the year For a journey …

As the camels lie in the snow and try to keep warm, the Magi dream of warm summer days. Eventually, after traveling at night and bypassing unfriendly towns, they arrive at the outskirts of Bethlehem, which is, “Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;/ With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness.”

Not exactly the way Christmas cards picture it.

Eliot has a unique way of writing.

His poems are full of jarring images and descriptions that don’t quite fit together, like camels in snow. He often collapses the past and the future into the present moment.

For instance, he does this in “The Journey of the Magi” by describing how the Magi set out from a foreign land, reach their destination, and then return home again. In this way, the circle is closed on the journey and those past events continue to affect the Magi. The journey is ever-present in their minds, the encounter with the Christ-child lingering to the extent that the Magi never quite feel the same again. They’re forever restless, almost as if Christ is pulling them into another life entirely.

For Eliot, “The Journey of the Magi,” marked something of a turning point in his artistic career. He wrote it in 1927 at the request of his publisher, Geoffrey Faber. The idea was that the poem would be set to a Christmas illustration and then sold as a popular memento. Although the poem has gained much praise over the years, Eliot at one point was nonchalant about it, saying, “I have no illusions about it: I wrote it in three quarters of an hour after church time and before lunch one Sunday morning, with the assistance of half a bottle of Booth’s gin.”

Later in his life, though, he did take the poem more seriously, commenting that writing it helped to get him out of a creative dry-spell and set him on the path to writing his famous poem “Ash Wednesday . “

More to the point, however, is the fact that around the time he wrote the poem, Eliot was beginning to take his Christian faith quite seriously. As an American who very much admired the English, he converted to a tradition within Anglicanism that imitated Catholic worship and many Catholic beliefs. This group, the “Anglo-Catholics,” was often mocked by other Anglicans for their “Romishness.” In many ways, Anglo-Catholicism is for those who love poetry, good wine, and tasteful dress — perfectly appealing for a man like T.S. Eliot, but underneath all the trappings is a serious faith tradition.

Eliot’s faith comes out in the sacramental nature of how he views Christmas.

Just as the sacraments overflow with superabundant grace, so too does Christmas. It’s a holiday that is ever so much more than it seems. It’s a special time during which everything takes on deeper meaning. You hug your kids more closely. The fire in the hearth burns more brightly. Generosity is in the air, an atmosphere of celebration. The season has a sense of enchantment that we look forward to all year. We can hardly wait to begin decking the halls with holly and putting inflatable Santas and reindeer on the front lawn.

At Christmas, there’s a collective feeling that life is a journey worth making. Like the Magi, we pause at the side of Christ in the manger and then circle back round again. Year after year.

In Eliot’s mind, even though the journey is long and difficult, it’s worth making because it unifies our hearts with that of God. Those images Eliot uses that seem so contradictory actually fold into a unity, the unifying love of God for his children. If, at Christmas, camels are yanked from the desert to camp in snow, it’s equally strange that Man and God should become so overlapped. This is the spark of grace. This is the miracle. God has become Man.

The Magi muse, “This: were we led all that way for/ Birth or Death?” In Eliot’s mind, each opposite contains the other. Our rebirth arises from the death of Christ, which was already foreordained even at Christmas. Our death to self for his sake assures this rebirth.

There is so much mystery here, so much grace. Each year, wherever life has taken us during this past orbit of the sun, we circle around to celebrate Christmas once again. The mystery only becomes more profound.

Articles like these are sponsored free for every Catholic through the support of generous readers just like you.

Help us continue to bring the Gospel to people everywhere through uplifting Catholic news, stories, spirituality, and more.

Horoscopes | Discover Your Free Daily Horoscope for April 18

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Entertainment

- Food & Drink

- Theater & Art

- Health & Fitness

- Home & Garden

Things to do

Unlock astrological insights and celebrate britt robertson’s journey on april 18.

Horoscopes | Dive Into Your Astrological Insights & Celebrate Luke Mitchell’s Star-Studded Birthday Today!

Horoscopes | Dive Into Your Free Daily Horoscope & Celebrate Sadie Sink’s Stellar Journey

Horoscopes | celebrate your free daily horoscope and the artistic versatility of danny pino, born april 15th, 1974.

Horoscopes | April 14 Horoscope: Astrological Insights & Celebrating Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Iconic Roles

Are you and your feline friend on the lookout for a new place to call home in Boulder, Colorado? Look...

When the time comes to bid farewell to a loved one, the support of a compassionate and professional funeral service...

Longmont, Colorado, nestled at the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, offers a blend of natural beauty, vibrant culture, and community...

In Loveland, Colorado, leather goods are not just accessories; they are a statement of style and durability. However, even the...

In the heart of the High Plains, where the soil breathes life into every seed planted, lies a trusted ally...

The Journey of the Magi (and Dan is back!) Urban Mystics

- Spirituality

The Journey of the Magi (Longing and Hope) The journey of the magi is an element of the Advent and Christmas story that relates deeply to a diverse range of human experience – from longing to wonder, from violence and despair to hope and justice. Join us this week as we continue in our Advent meditation series. Dan is back! And we invite you to respond to the hope and anticipation of the season as the magi respond to the sign of the newborn king – with a presentation of gifts and reverence. This episode is written and hosted by Dan Lee and produced by Tony Duppong, exclusively for the Urban Mystics Podcast. Learn more about Urban Mystics by visiting the Urban Mystics website or by joining the new ReWire Hub community and checking out the Urban Mystics space. Find us on Instagram or send us an email at [email protected] Meditations and recordings are property of Urban Mystics. Use of this copyrighted material is not allowed without consent. Episode Audio Credits: Music by SOUNDS FROM AFRICA from Pixabay Space Atmospheric Background from Pixabay

- Episode Website

- More Episodes

- Tony Duppong and Dan Lee

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

.jpg)

Bye, Barbie! Margot Robbie Tries Out 2024’s Biggest Hair Cut And Color Trend

By Philipp Wehsack

There’s no question that 2023 was Margot Robbie’s year. The blockbuster movie Barbie catapulted the actor back onto our screens as a life-size version of the globe’s favorite doll, sending her fame level into the stratosphere. She even transformed into Barbie on the red carpet during the film’s premieres and award season. Robbie’s method dressing informed her hair and makeup, with long, bouncy blonde hair and fresh, flushed make-up. Until now…

Goodbye Barbie blonde!

On set in LA this week for A Big, Bold, Beautiful Journey , which is rumored to be released next year, Robbie was spotted with both a new hairstyle and color. Instead of her distinctive golden Barbie blonde, Robbie was seen one of the year's biggest hair color trends–“old money blonde” with a subtle red hue. The ashy blonde with a hint of copper gives the darker blonde shade more shine as it helps the blonde color shine when light hits it. The reason for the change is no doubt part of her transformation into the character Robbie is playing in the film, but like her Barbie -core style, it’s another winning beauty look.

It’s not just Robbie’s hair color that’s had an update, the actor now has a fresh on-trend fringe. The wispy bangs have a nod to the ’90s, framing Robbie’s face with cleverly feathered pieces and longer side sections giving the fringe an effortless style. Similar to curtain bangs, this wispy fringe style is the perfect noncommittal hairstyle change as it grows out more easily than blocky bangs. Robbie, yet again, proves she’s a beauty chameleon.

Vogue Beauty