UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

The first global dashboard for tourism insights.

- UN Tourism Tourism Dashboard

- Language Services

- Publications

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

UN Tourism Data Dashboard

The UN Tourism Data Dashboard – provides statistics and insights on key indicators for inbound and outbound tourism at the global, regional and national levels. Data covers tourist arrivals, tourism share of exports and contribution to GDP, source markets, seasonality and accommodation (data on number of rooms, guest and nights)

Two special modules present data on the impact of COVID 19 on tourism as well as a Policy Tracker on Measures to Support Tourism

The UN Tourism/IATA Destination Tracker

Un tourism tourism recovery tracker.

UN Tourism Tourism Data Dashboard

- International tourist arrivals and receipts and export revenues

- International tourism expenditure and departures

- Seasonality

- Tourism Flows

- Accommodation

- Tourism GDP and Employment

- Domestic Tourism

International Tourism and COVID-19

- The pandemic generated a loss of 2.6 billion international arrivals in 2020, 2021 and 2022 combined

- Export revenues from international tourism dropped 62% in 2020 and 59% in 2021, versus 2019 (real terms) and then rebounded in 2022, remaining 34% below pre-pandemic levels.

- The total loss in export revenues from tourism amounts to USD 2.6 trillion for that three-year period.

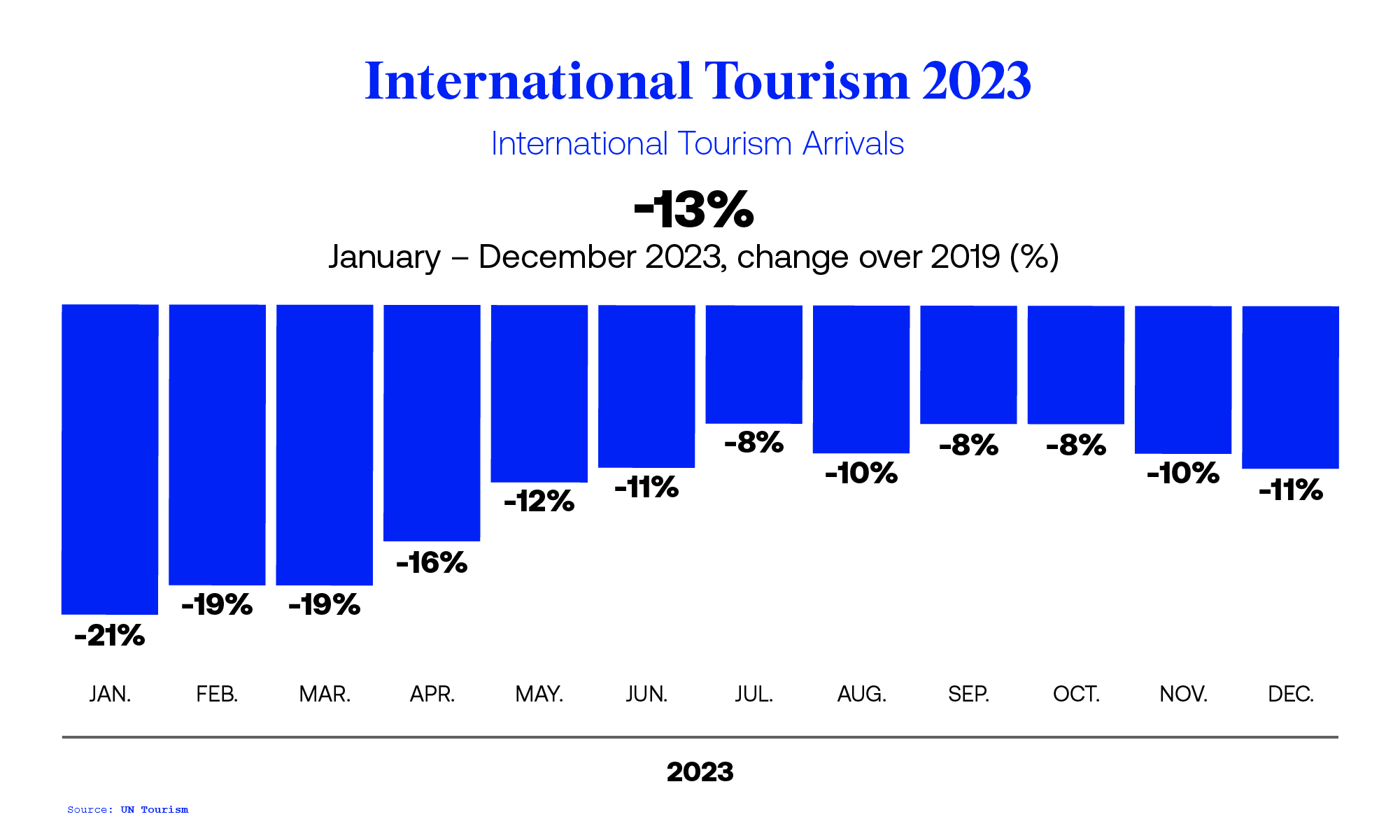

- International tourist arrivals reached 88% of pre-pandemic levels in January-December 2023

COVID-19: Measures to Support Travel and Tourism

US Travel Header Utility Menu

- Future of Travel Mobility

- Travel Action Network

- Commission on Seamless & Secure Travel

- Travel Works

- Journey to Clean

Header Utility Social Links

- Follow us on FOLLOW US

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on LinkedIn

- Follow us on Instagram

- Follow us on Facebook

User account menu

Travel price index.

MONTHLY INSIGHTS December 20, 2023

The Travel Price Index (TPI) measures the cost of travel away from home in the United States. It is based on the U.S. Department of Labor price data collected for the monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI). The TPI is released monthly and is directly comparable to the CPI.

Please see attached table for the latest data.

Member Price: $0

Non-Member Price: $0 Become a member to access.

- Press Releases

- Press Enquiries

- Travel Hub / Blog

- Brand Resources

- Newsletter Sign Up

- Global Summit

- Hosting a Summit

- Upcoming Events

- Previous Events

- Event Photography

- Event Enquiries

- Our Members

- Our Associates Community

- Membership Benefits

- Enquire About Membership

- Sponsors & Partners

- Insights & Publications

- WTTC Research Hub

- Economic Impact

- Knowledge Partners

- Data Enquiries

- Hotel Sustainability Basics

- Community Conscious Travel

- SafeTravels Stamp Application

- SafeTravels: Global Protocols & Stamp

- Security & Travel Facilitation

- Sustainable Growth

- Women Empowerment

- Destination Spotlight - SLO CAL

- Vision For Nature Positive Travel and Tourism

- Governments

- Consumer Travel Blog

- ONEin330Million Campaign

- Reunite Campaign

Economic Impact Research

- In 2023, the Travel & Tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP; an increase of 23.2% from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 level.

- In 2023, there were 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level.

- Domestic visitor spending rose by 18.1% in 2023, surpassing the 2019 level.

- International visitor spending registered a 33.1% jump in 2023 but remained 14.4% below the 2019 total.

Click here for links to the different economy/country and regional reports

Why conduct research?

From the outset, our Members realised that hard economic facts were needed to help governments and policymakers truly understand the potential of Travel & Tourism. Measuring the size and growth of Travel & Tourism and its contribution to society, therefore, plays a vital part in underpinning WTTC’s work.

What research does WTTC carry out?

Each year, WTTC and Oxford Economics produce reports covering the economic contribution of our sector in 185 countries, for 26 economic and geographic regions, and for more than 70 cities. We also benchmark Travel & Tourism against other economic sectors and analyse the impact of government policies affecting the sector such as jobs and visa facilitation.

Visit our Research Hub via the button below to find all our Economic Impact Reports, as well as other reports on Travel and Tourism.

An official website of the United States government

- Special Topics

Travel and Tourism

Travel and tourism satellite account for 2017-2021.

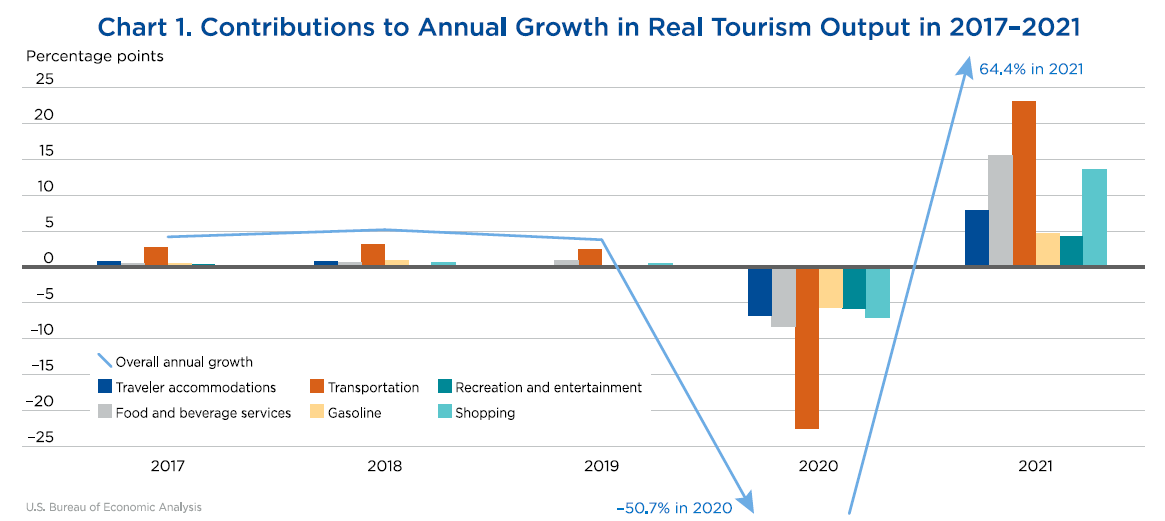

The travel and tourism industry—as measured by the real output of goods and services sold directly to visitors—increased 64.4 percent in 2021 after decreasing 50.7 percent in 2020, according to the most recent statistics from BEA’s Travel and Tourism Satellite Account.

Data & Articles

- U.S. Travel and Tourism Satellite Account for 2017–2021 By Sarah Osborne - Survey of Current Business February 2023

- "U.S. Travel and Tourism Satellite Account for 2015–2019" By Sarah Osborne - Survey of Current Business December 2020

- "U.S. Travel and Tourism Satellite Account for 2015-2017" By Sarah Osborne and Seth Markowitz - Survey of Current Business June 2018

- Tourism Satellite Accounts 1998-2019

- Tourism Satellite Accounts Data Sheets A complete set of detailed annual statistics for 2017-2021 is coming soon -->

- Article Collection

Documentation

- Product Guide

Previously Published Estimates

- Data Archive This page provides access to an archive of estimates previously published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Please note that this archive is provided for research only. The estimates contained in this archive include revisions to prior estimates and may not reflect the most recent revision for a particular period.

- News Release Archive

What is Travel and Tourism?

Measures how much tourists spend and the prices they pay for lodging, airfare, souvenirs, and other travel-related items. These statistics also provide a snapshot of employment in the travel and tourism industries.

What’s a Satellite Account?

- TTSA Sarah Osborne (301) 278-9459

- News Media Connie O'Connell (301) 278-9003 [email protected]

By Bastian Herre, Veronika Samborska and Max Roser

Tourism has massively increased in recent decades. Aviation has opened up travel from domestic to international. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of international visits had more than doubled since 2000.

Tourism can be important for both the travelers and the people in the countries they visit.

For visitors, traveling can increase their understanding of and appreciation for people in other countries and their cultures.

And in many countries, many people rely on tourism for their income. In some, it is one of the largest industries.

But tourism also has externalities: it contributes to global carbon emissions and can encroach on local environments and cultures.

On this page, you can find data and visualizations on the history and current state of tourism across the world.

Interactive Charts on Tourism

Cite this work.

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Role of tourism price in attracting international tourists: The case of Japanese inbound tourism from South Korea

a Apparel, Events and Hospitality Management, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA

Choong-Ki Lee

b Department of Tourism, Kyung Hee University, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130-70, South Korea

Tourism price has been extensively used to predict tourism demand. However, there is no agreement on the proper indicators of its components. Use of different price indicators may be the reason for researchers’ apparently inconsistent results. The purpose of this study was to identify proper price indicators for the demand model of Japanese inbound tourism from South Korea. After comparing six models, each with different price indicators, the model with relative price and exchange rate but without transport cost was identified as the best model in which relative price, exchange rate, and per capita income were found to be significant.

- • The effect of tourism price variables on inbound tourism demand is examined.

- • Exchange rates and relative prices separately lead to increase in tourist arrivals.

- • Both proxy variables for transport cost appear to have no influence on tourism.

- • Price competitiveness can contribute to stimulating international tourism demand.

- • Government policy should be developed considering its impact on tourism prices.

1. Introduction

International tourism has experienced sustained expansion over the past six decades, substantially contributing to the world economy. International tourist arrivals reached the unprecedented milestone of 1 billion in 2013 and generated US$476 billion in expenditures ( World Tourism Organization, 2014 ). Accordingly, many researchers have conducted studies on international tourism flows and their major determinants ( Carey, 1991 , Chatziantoniou et al., 2013 , De Vita and Kyaw, 2013 , Garín-Muñoz, 2006 , Law et al., 2004 , Lee, 1996 , Wang, 2009 ).

Tourism demand forecasting is important for effective use of limited resources in both private and public sectors ( Lee et al., 1996 , Song and Witt, 2006 ). Since many tourism products such as airline seats and hotel rooms are perishable, efficient planning based on accurate estimation of demand is critical for successful tourism businesses. An inability to meet demand often leads to business failure in the tourism industry ( Song & Witt, 2006 ). For the public sector, tourism forecasting provides a basis for planning investments in tourism infrastructure such as airports and highways ( Lee, Song, & Mjelde, 2008 ). Since such large-scale infrastructure projects require considerable public funds over the long term, the expected return on investment (ROI) should be spelled out in the planning stages, and ROI is in large part determined by forecasting tourism demand. Accordingly, accurate demand estimation is essential when appraising investment plans’ economic feasibility ( Song & Witt, 2006 ).

Recognizing the importance of tourism demand forecasting, the econometric approach has been widely adopted to predict tourism demand ( Song & Li, 2008 ). In econometric studies of tourism demand, per capita income, tourism price, promotional efforts, and external shocks have been identified as important determinants of tourism demand ( Li et al., 2005 , Lim, 1999 , Song and Li, 2008 ). However, results regarding the effects of price variables (e.g.relative prices, exchange rates, transport cost) on international tourism demand vary widely. Some inconsistent results may be attributable to use of different variables as a proxy for the same tourism price factor. This inconsistent use of price variables suggests that more research needs to be done to identify the price variables that best represent international tourism price.

Given that previous empirical studies yielding the inconclusive results on price effect have been conducted in the context of different countries, proper price variables may be different from destination to destination. Indeed, tourists’ responses to changes in explanatory variables are country-specific and therefore the variables’ elasticity varies by destinations ( Crouch, 1995 , Dwyer et al., 2000 , Gil-Pareja et al., 2007 ). Moreover, recent changes in economic circumstances such as currency depreciation resulting from unconventional monetary policy (US, Eurozone, Japan), shifts in exchange rate policy (Switzerland, Singapore, China), and drastic drops in oil prices triggered by expanded supplies of shale gas may substantially influence the cost of travel to the countries changing international tourism demand. Thus, choosing the proper price variables for the tourist destinations examined could be critical to the accurate estimation of tourism demand for those destinations.

The aim of this study is to address the selection of proper tourism price variables in identifying underlying factors in tourism demand model. Specifically, this study estimates and compares several demand models of Japanese inbound tourism from South Korea (hereafter Korea), each of which includes different price variables. Japanese inbound tourism from Korea was chosen for the following reasons: (1) Korea is the largest tourism market for Japan; and (2) price variables have a clear effect on tourism demand, as shown by the fact that the Japanese yen (JPY) has depreciated against the Korean won (KRW) from the fourth quarter of 2011 to the third quarter of 2014. The findings of this study contribute to a better understanding of price variables when forecasting international tourism demand for a specific country. In addition, because the Japanese government intends to increase its annual tourist arrivals to 20 million by 2020 when Japan hosts the Tokyo Olympics ( Ong, 2014 ), identifying determinants of tourism demand for Japan is of great importance for both policymakers and tourism practitioners.

2. Literature review

Tourism demand studies fall into two categories: qualitative and quantitative ( Peng, Song, & Witt, 2012 ). Quantitative demand studies are dominant in the tourism demand literature ( Song & Turner, 2006 ) and two forecasting approaches are the most commonly used: time-series and econometric ( Song & Li, 2008 ). The time-series approach is useful in that estimation procedures are relatively simple and only one data series is needed for estimation ( Peng et al., 2012 ). In this approach, demand forecasting is performed by analyzing the patterns of past demand movements and then, from that, predicting future movements ( Song & Li, 2008 ). On the other hand, the econometric approach predicts tourism demand based on the causal relationship between dependent (e.g. tourists) and explanatory (e.g. income) variables with sound theoretical basis ( Peng et al., 2012 ). The empirical usefulness of this approach lies in identifying which factors contribute most to tourism demand ( Lee et al., 1996 , Song et al., 2009 ).

2.1. Price factors affecting international tourism demand

In econometric tourism demand studies, several economic factors have been found to be significant determinants of international tourism demand ( Prideaux, 2005 ). Based on classic economic demand theory (i.e. the higher the prices of goods and services, the lower the demand for those products), tourism price has been commonly used in demand models as a primary determinant ( Hui and Yuen, 1998 , Uzama, 2009 ). According to Crouch (1994) , Witt and Witt (1995) , and Webber (2001) , tourism price consists of living cost plus transport cost. Living cost, in turn, has two components: prices of tourism goods and services in the destination country and exchange rates.

In general, prices of tourism goods and services have a negative relationship with tourism demand. The relationship may be sensitive to changes in domestic tourism prices in the origin country and therefore many demand models include prices of destination tourism products relative to the origin country in order to consider the cross-price effect ( Loeb, 1982 , Tan et al., 2002 ). Because price information of tourism goods and services is generally unavailable, consumer price index (CPI) has commonly been used as a proxy for relative prices ( Akis, 1998 , Lee, 1996 , Morley, 1994 ; Muchpondwa & Pumhidzai, 2011 ). Furthermore, actual prices of a destination's tourism products have not been found to be clearly superior to CPI in accounting for tourism demand ( Martin & Witt, 1988 ). Although CPI is most commonly used for relative prices ( Akis, 1998 ), Gil-Pareja et al. (2007) included purchasing power parity in their demand model instead of CPI and Garín-Muñoz (2006) developed her own tourism price index.

Many studies have proved that tourism demand is significantly responsive to changes in relative prices ( Eilat & Einav, 2004 ; Hiemstra & Wong, 2002 ; Patsouratis, Frangouli, & Anastasopoulos, 2005 ; Qu & Lam, 1997 ; Webber, 2001 ). For example, Webber (2001) identified the determinants of tourism demand for Australia in eight tourism markets using Engle and Granger's procedure and Johansen's procedure. The results showed that relative prices had a significantly negative effect on tourist arrivals from six of the eight countries, all but Malaysia and the U.K. Hiemstra and Wong (2002) investigated the outbound tourism from seven major countries to Hong Kong between 1990 and 1998. In the study, autoregressive estimation was employed for seven tourism demand models and relative prices were included only in the demand model for Australia–Hong Kong. The results of the study provided clear evidence of a significant effect of relative prices on tourist arrivals from Australia to Hong Kong. On the other hand, Muchpondwa and Pimhidzai (2011) found no link between relative prices and tourism demand. Lee et al. (1996) showed that the significant effects of relative prices on international tourism demand varied depending on the origin country to country indicating mixed results.

Exchange rates, the other indicator of living cost, have also been frequently examined in tourism demand studies (e.g., De Vita & Kyaw, 2013 ; Di Matteo & Di Matteo, 1996 ; Dritsakis & Gialetaki, 2004 ; Edward, 1995 ; Wang, 2009 ; Yap, 2011 ). When the currency of a country devalues, its tourism becomes more price competitive and therefore travel demand for the country is likely to increase ( De Vita & Kyaw, 2013 ). Conversely, as the value of a country's currency rises, the decreased price competitiveness of its tourism results in a reduction in inbound tourism ( De Vita, 2014 ). However, this view has not always been borne out in international tourism markets. Some researchers (e.g. Di Matteo & Di Matteo, 1996 ; Eilat & Einav, 2004 ; Hiemstra & Wong, 2002 ; Roselló-Villalonga, Aguiló-Pérez, & Riera, 2005 ; Wang, 2009 ) have found evidence that exchange rates have a significant effect on tourism demand, while others (e.g. Hui & Yuen, 1998 ; Muchapondwa & Pimhidzai, 2011 ; Webber, 2001 ) failed to find such evidence. In addition, Lee (1996) developed several demand models for inbound tourism to Korea and the results of exchange rate were inconsistent. These results indicate that the effects of exchange rates are asymmetric across countries and even across different markets in a single country.

It has generally been held that relative prices and exchange rates should be considered in tourism demand models, but it remains controversial whether these two components of living cost should be examined separately or combined as effective relative prices ( Durbarry and Sinclair, 2003 , Gray, 1966 , Tan et al., 2002 ). According to Song and Witt (2000) , price changes in a destination country can be calibrated by movements in exchange rate. Therefore, the destination price level that potential foreign tourists pay attention to is relative prices adjusted by exchange rates. Based on this argument, many researchers (e.g. Chang, Khamkaew, & McAleer, 2010 ; Divisekera, 2003 ; Garín-Muñoz, 2006 ; Kliman, 1981 ) convert relative prices into the currency of an origin country in tourism demand equations. Numerous studies (e.g. De Vita, 2014 ; Divisekera, 2003 ; Durbarry & Sinclair, 2003 ; Hiemstra & Wong, 2002 ) have argued for the significance of effective relative prices. Tan et al. (2002) concluded that effective relative prices were a better measure of living costs for Malaysian and Indonesian tourism. In contrast, Eilat and Einav (2004) and O’Hagan and Harrison (1984) argue that relative prices and exchange rates should enter separately into tourism demand models because it is highly likely that tourists will have more up-to-date information on exchange rates than on relative prices. Accordingly, they are more likely to use exchange rates to estimate cost of travel to the destination. Moreover, it has been noted that responsiveness of tourists to exchange rates is distinctive from their responsiveness to changes in relative prices ( Gray, 1966 , Lee, 1996 , Muchapondwa and Pimhidzai, 2011 ). With this in mind, many researchers (e.g. De Vita & Kyaw, 2013 ; Di Matteo & Di Matteo, 1996 ; Eilat & Einav, 2004 ; Edward, 1995 ; Wang, 2009 ) have included exchange rates as a separate variable in their tourism demand equations.

Transport cost is also a component of tourism price. As transport cost accounts for a large proportion of total travel cost, an increase in transport cost tends to negatively affect destination choice with a subsequent decline in tourism flows ( Covington et al., 1995 , Divisekera, 2003 ). Airfares, oil prices, or distance have been typically used as proxies for transport cost ( Durbarry and Sinclair, 2003 , Kulendran and Witt, 2001 , Song and Witt, 2000 ). Kulendran and Witt (2001) compared the forecasting performance of cointegration and least-squares regression models, indicating that transport cost represented by airfares significantly influenced outbound tourism flows from the U.K. Nelson, Dickey, and Smith (2011) conducted time-series and cross-section analyses to investigate tourism from the US mainland to Hawaii. Airfare was found to be a significant determinant of tourism demand for Hawaii.

Since transport cost changes as a function of fuel costs and geographical distance, oil prices and distance between two countries have been added to demand models as a proxy for transport cost ( Hiemstra & Wong, 2002 ). For example, Wang (2009) employed the autoregressive distributed lag model to identify the determinants of Taiwan's inbound tourism, particularly focusing on the effect of disastrous events. The study reported that oil prices had a significantly negative effect on Taiwan tourism indicating that foreign tourists are less likely to visit Taiwan as transport cost rises. De Vita (2014) used a distance variable to approximate transport cost through a gravity-type tourism demand equation and found distance was significant on tourism demand for 27 countries. The popular use of gravity models in tourism demand studies has allowed extensive investigation of the explanatory power of distance. Such studies include Eryiğit, Kotil and Eryiğit (2010) , Park and Jang (2014) , and Uysal and Crompton (1984) . However, oil prices and distance may be inappropriate for representing transport costs since neither variable considers the other, but both are main elements of the fuel cost function. Airfares are also limited due to complex fare structures and lack of data availability ( Song and Witt, 2000 , Webber, 2001 ).

2.2. Japanese inbound tourism and its relation to Korea

As one contributor to the increasing trend in international tourism, Japanese inbound tourism has increased from 0.7 million arrivals in 1971 to 13.4 million arrivals in 2014 ( Japan National Tourist Organization, 2015 ). Despite occasional crisis events (e.g. the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear power plant), Japanese inbound tourism continues to grow. From 1971 to 2014, the annual growth rate was 7.2% on average and the figure has accelerated in recent three years averaging 29.3% along with considerable depreciation of the currency (50.3%). As a result, Japan has the sixth largest international tourism share among Asian countries ( World Tourism Organization, 2014 ).

Three East Asian countries – China, Korea, and Taiwan – accounted for approximately 60% of Japan's inbound tourism market in terms of number of tourist arrivals ( Japan National Tourist Organization, 2014 ). Among these countries, Korea has been the biggest market for Japan for the last two decades. Korean tourists to Japan has increased from 0.7 million in 1990 to 2.5 million in 2013 (see Fig. 1 ) and their share of the Japanese inbound tourism market was between 17.6% and 31.2% ( Japan National Tourist Organization, 2014 ). Despite the importance of Korea in the Japanese tourism industry, few studies have examined the determinants of the Korean demand for Japan tourism.

Korean tourist arrivals to Japan, 1990-2013.

There has been extensive exchange between Korea and Japan and in various areas such as economy, culture, politics, and diplomacy because of their geographic proximity. The major presence of Korea in Japanese tourism may be a result of the strong ties established in the various areas ( Lee, Song, & Bendle, 2010 ). Moreover, due to geographic proximity and the strong ties between the two countries, Koreans are likely to be aware of Japanese economic conditions and thus reasonably responsive to changes in Japanese tourism price. Accordingly, the impact of the different price variables of Japan tourism, whether positive or negative, can be readily captured in relation to Korea.

3. Methodology

3.1. model estimation.

This study developed tourism demand models from Korea to Japan between the first quarter of 2000 and the fourth quarter of 2014. The dependent variable ( RTOUR t ) was the number of Korean tourists divided by the total population of Korea. The use of population as a deflator was done to control for the increase in Korean tourists caused merely by population growth.

Based on classic demand theory in which demand is a function of product price and individual income, two economic variables influencing demand for international tourism were added to the models: per capita income and tourism price. As the most important determinant of international tourism, per capita income is a measure of individual spending power. An increase in individual income is likely to lead to greater spending power creating tourism demand. This variable was calculated as the gross domestic product (GDP) of Korea divided by its population and then converted into real per capita income ( RINCOME t ) by dividing per capita income by Korean CPI.

To investigate the price effect on Japanese inbound tourism from Korea, this study used relative prices, effective relative prices, exchange rates, oil prices, and jet-fuel prices. For the selection of adequate price variables, this study developed and compared six demand models with different price variables as follows:

The first model included relative prices and exchange rates separately to measure living cost in Japan. Relative price ( RPRC t ) was calculated as the ratio of Japanese CPI to Korea CPI and exchange rate ( EXC t ) was measured as the value of JPY per KRW. The second model added oil prices as a proxy for transport cost. Real oil price ( ROIL t ) was computed by dividing crude oil prices per gallon by Korean CPI. The third model used jet-fuel prices as a proxy for transport cost instead of oil prices. Despite the importance of distance in transport cost functions, oil price variable does not reflect the distance between two countries. In addition, crude oil may have different price movement from the jet fuel actually used by aircraft. Thus, this study developed a variable of jet-fuel prices as new proxy for transport cost, since it takes into account both distance and actual fuel price. Real jet-fuel price ( RJET t ) was calculated as (jet-fuel prices per gallon×(distance/average fuel efficiency per seat))/Korean CPI.

In the fourth model, a combined variable, effective relative price ( RPRC t ), was used to represent living cost. Effective relative price ( E RPRC t ) was calculated by adjusting relative price ( RPRC t ) with exchange rate ( EXC t ). The fifth model added real oil price ( ROIL t ) to the explanatory variables used in the fourth model. In the sixth model, real jet-fuel price ( RJET t ) replaced real oil price ( ROIL t ) used in the fifth model.

In addition to the economic variables, five binary dummy variables were included in our models to take into account the effect of special events. To account for the impacts of radiation risk in Fukushima and the visa-free entry (VFE) program, two dummy variables ( DM NUCLEAR , DM VFE ) were added. Since nuclear leakage is a continuing concern and the VFE program is still in place, these dummy variables were coded as one after their starting date (the first quarter of 2006 for VFE and the first quarter of 2011 for Fukushima) and zero before that. Three other events that might affect outbound tourism from Korea – the 2002 Korea–Japan World Cup in the second quarter of 2002, SARS from the fourth quarter of 2002 through the second quarter of 2003, and the global financial crisis from the third quarter of 2008 through the fourth quarter of 2009 – were investigated through the inclusion of three dummy variables ( DM WCUP , DM SARS , and DM ECRISIS ). Finally, seasonal dummy variables ( DM SEA , i ) were added to control for seasonal effects. The base group was the fourth quarter. The expected signs for the variables were: REXC t , RINCOME t , DM VFE , DM SEASON >0 and RPRC t , ERPRC t , ROIL t , RJET t , DM WCUP , DM SARS , DM FCRISIS , DM NUCLEAR <0.

As in most previous tourism demand studies, our models used a double log-linear function. The double log specification allows researchers to interpret the coefficients as elasticity. Preliminarily, serial correlation of the six models was assessed using the Durbin-Watson test and Breusch–Godfrey test. Because both of the tests found serial correlation in all models, this study employed Prais–Winsten estimation, one type of feasible generalized least squares (FGLS), to estimate the six demand models.

3.2. Data sources

The study period was from the first quarter of 2000 to the third quarter of 2014. Quarterly number of Korean tourist arrivals was obtained from the Japan National Tourist Organization (2015) . For computation of explanatory variables, economic indices were acquired from the databases of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015) , the Japan Tourism Marketing (2015) , and the Statistics Korea (2015) . Quarterly jet-fuel prices were obtained from the database of the US Department of Transportation (2015) . Data on fuel efficiency per seat was acquired from the websites of two commercial aircraft manufacturers, Boeing and Airbus (see http://www.airbus.com and http://www.boeing.com ). The distance between Korea and Japan was derived from the dataset of Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (2015) used in previous demand studies (e.g. De Vita, 2014 ; Park & Jang, 2014 ).

Bilateral correlation of variables is shown in Table 1 . While Pearson correlation analysis was performed for continuous variables, the point-biserial correlation method was applied to the pairs of continuous and binary variables. Phi correlation was used when both variables had binary values. Point-biserial correlation and phi correlation are equivalent to Pearson correlation ( Revelle, 2008 , Gould and Rogers, 1992 ). The results showed that none of the explanatory variables were highly correlated indicating that the estimated models did not have multicollinearity problems which can reduce the overall data fit of a model and increase the variance of coefficients, decreasing the model's statistical power ( Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010 ).

Correlation analysis.

Note. Pearson coefficients for continuous variables, point-biserial coefficients for pair of continuous and binary variables, phi coefficients for binary variables.

Table 2 summarizes the results of model estimation. The results showed that all six models explained more than 70% of the variance in Korean tourist arrivals to Japan. In terms of R 2 , (Model 1) , (Model 2) , (Model 3) which treated relative price ( RPRC t ) and exchange rate ( EXC t ) separately appeared to provide a better fit to the data than (Model 4) , (Model 5) , (Model 6) which used effective relative price ( ERPRC t ). (Model 1) , (Model 2) , (Model 3) were nested because Model 1 could be obtained from (Model 2) , (Model 3) . Model 4 and (Model 5) , (Model 6) were nested in the same way. Model 1 (or Model 4 ) was the restricted model for the full models of (Model 2) , (Model 3) (or (Model 5) , (Model 6) ). Based on these relationships, rigorous model selection analysis was performed.

Results of model estimation.

Note. RTOUR t is the dependent variable for all six models. * p <0.05; ** p <0.01.

Using a partial F-test, we checked whether the restricted models without a transport cost variable showed a significant difference in overall model fit to data compared to the full models. The partial F-test results revealed no significant differences in overall fit between all nested model pairs (see Table 3 ). This indicates that the removal of transport cost variables from the full models does not significantly change the explained variance in Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. In terms of model parsimony, Model 1 was better than (Model 2) , (Model 3) , and Model 4 was better than (Model 5) , (Model 6) .

Results of partial F -tests.

Note. Model 1 is the restricted model for the full models of Models 2 and 3, and Model 4 is for Models 5 and 6.

Since a partial F-test can be used only for nested models, this study employed Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to compare nested and un-nested models together ( Burnham and Anderson, 2004 , Cavanaugh, 2012 ). The results of AIC presented in Table 4 showed that the models using relative price ( RPRC t ) and exchange rate ( EXC t ) had relatively lower AIC than the models with effective relative price ( ERPRC t ). Among the models using relative price ( RPRC t ) and exchange rate ( EXC t ), the AIC of Model 1 was the lowest, suggesting that Model 1 offers the best fit to the data, having the smallest information loss.

Results of AIC and BIC.

Since model selection analysis identified Model 1 as the best model, this study presents the coefficient estimation results from Model 1 . The living cost variables represented by relative price ( RPRC t ) and exchange rate ( EXC t ) accounted for a significant amount of the changes in Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. The coefficients show that a 1% decrease in relative price ( RPRC t ) results in a 2.3% increase in Japanese inbound tourism from Korea and that a 1% depreciation in JPY (or a 1% appreciation in KRW) leads to a 0.7% increase in Japanese inbound tourism from South Korea. Real per capita income ( RINCOME t ) also had a significant impact on international tourism demand to Japan from Korea: a 1% increase in Koreans’ individual income results in a 1.2% increase in tourism demand for Japan.

The coefficients of dummy variables for the special events had the expected signs except for the dummy for 2002 World Cup. However, only the dummies for the financial crisis ( DM FCRISIS ) and the Fukushima nuclear disaster ( DM NUCLEAR ) had a significant effect on Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. Seasonal dummy variables were also significant. Specifically, the dummies for the first and the third quarters were significantly positive, implying that Korean tourists visit Japan mainly in summer and winter.

5. Conclusions and implications

This study compared six tourism demand models, each with different price variables, to identify proper price variables affecting Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. Partial F-test based on the nested (or hierarchical) relationship of demand models and AIC analysis were used for model comparison. The results of this study showed that separate inclusion of relative prices and exchange rates was more effective in accounting for the changes in Japanese inbound tourism from Korea than a price variable combining these two price indicators. Model comparison results also showed that exclusion of a transport cost variable did not decrease the explanatory power of the models. This study has several theoretical, methodological, and practical implications.

In terms of theory, the results confirm the view that exchange rates should be treated separately in tourism demand models because exchange rates are often used for destination selection apart from relative prices ( Muchapondwa and Pimhidzai, 2011 , O’Hagan and Harrison, 1984 , Witt and Witt, 1990 ). Some researchers ( Gray, 1966 , Lee, 1996 ) argue that the price level actually recognized in origin countries is highly dependent on exchange rates and therefore foreign tourists’ responses to changes in exchange rates are very different from their responses to relative prices. This view is supported by the argument that when potential tourists cannot obtain updated information on tourism prices, they tend to use the exchange rates, which is readily available to the public ( Muchapondwa and Pimhidzai, 2011 , Webber, 2001 ). Considering this, it is notable that exchange rates are an important consideration in destination selection even though Koreans may be well aware of the prices of Japanese tourism products due to the two countries’ proximity and sustained active relationship. This suggests that it is not easy, even between closely associated countries, for foreign consumers to gain knowledge of destination prices or accurately update their existing price knowledge over time. Either case may lead them to use the current exchange rates in their travel decisions. Thus, this study's significant contribution is to extend existing tourism demand literature by empirically identifying two price variables used for tourism destination choice in the Korea-to-Japan context.

In the identified model, per capita income was significant on Japanese tourism demand from Korea. This result is consistent with previous studies (e.g. Garín-Muñoz, 2006 ; Lee, 1996 ; Webber, 2001 ) which found this variable to be an important determinant of tourism demand. Two separate price variables were also significant determinants. The significant results for relative prices, exchange rates, and per capita income support the application of the classic demand theory to Japanese inbound tourism. The results also indicate that the demand for Japan tourism by Koreans can be effectively estimated without considering transport cost. This implies that changes in transport cost do not affect Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. Two different measures of transport cost, oil price and jet-fuel price, were indeed found to be unrelated to changes in Japanese inbound tourism from Korea in the full models. The results suggest that tourists planning short-haul international travel are less likely to take into account the cost of transport to their destination. As a result, caution should be exercised in including transport cost in modeling the demand for short-haul international travel.

In addition to the theoretical implications previously discussed, this study has important methodological implications. In an attempt to identify proper price variables, this study demonstrated model comparison methods for nested models (partial F-test and AIC) and for un-nested models (AIC) ( Bowerman and O’Connell, 1990 , Burnham and Anderson, 2004 ). By developing new measures of transport cost which consider actual aircraft fuel prices and the distance between two countries, this study tried to address the limitations of using oil price and distance as a sole proxy for transport cost.

Practical implications are also evident from the results of this study. This study found evidence for the significance of per capita income. In other words, outbound tourism from Korea to Japan is sensitive to movements in the Korean economy. This suggests that economic growth in Korea generates a significant increase in the Korean demand for tourism to Japan. Although destination countries have limited ability to influence per capita income of inbound tourists, since it is mainly affected by economic conditions in origin countries, destination countries can still take advantage of this characteristic. For example, when Japanese inbound tourism from Korea shrinks due to a local or global recession, Japan's tourism industry could counter this loss by reallocating their promotional resources to tourism markets experiencing an economic boom or less economy-sensitive markets. To implement this strategy, Japan would need to monitor economic conditions in Korea and its other major tourism markets such as China, Taiwan, and the US.

As discussed earlier, relative prices and exchange rates had a significant effect on Japanese inbound tourism demand from Korea. Combined with the results for other explanatory variables in the most appropriate model, this shows that relative prices contribute the most to Japan's inbound tourism in terms of elasticity and indicates that prices of tourism products are the most important factor in the choice of destination by tourists. Given that prices of tourism products are manageable by destination country or tourism industry to a certain extent, and the importance of price in attracting international tourists to Japan, a solid pricing strategy is critical for the Japanese tourism industry to maintain destination competitiveness. Some researchers (e.g. Bowen, 1998 ; Griffin, Shea & Weaver, 1997 ; Papadopoulos, 1989 ) have emphasized the importance of the price competitiveness of Japanese tourism products with those of neighboring countries such as China and Korea, which provide relatively cheap tourism products. For price competitiveness, the relentless efforts of the private sector, including cost reduction, new technology adoption, and research and development, should be made on a continuous basis ( Blake et al., 2006 , Dwyer and Kim, 2003 ). In the same vein, government is of great importance in providing sustainable price-competitive tourism products. The recent jump in tourist arrivals to Japan, for example, was triggered by a sharp decline in the value of JPY resulting from Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe's economic policy known as 'Abenomics' ( Ong, 2014 ). This indicates that government economic policy is likely to influence tourism demand by altering economic conditions, which are responsible for the prices of tourism products ( Edward, 1995 , Eilat and Einav, 2004 ). Furthermore, governments could offer tax credits for international tourists’ expenditures ( Dimanche, 2003 ) and tax incentives to tourism firms which undertake extensive overseas marketing campaigns, hold international meetings, and renovate or replace their facilities ( Blake and Sinclair, 2003 , McKehee and Kim, 2004 ). Great care must therefore be taken in formulating tourism and economic policies in order to promote international tourism through price competitiveness and stability.

As with many other tourism demand studies, this study is not without limitations. First, the relatively small subject pair and sample observations may limit the generalizability of the results. Second, although none of the explanatory variables could be excluded due to multicollinearity, the variables may not be totally free from the multicollinearity problem given that significant correlations exist between the variables. One way to overcome the first limitation would be to use panel data. Examining the relationship between different price variables and tourism arrivals in the context of multiple tourism markets would improve the generalizability of the variable selection results. For the second limitation, it would be worthwhile employing dynamic factor analysis, a time-series extension of factor analysis proposed by Geweke (1977) . By applying factor analysis to multivariate time series data, dynamic factor analysis can address the correlation between explanatory variables and data stationarity ( Stock & Watson, 2011 ). Third, this study used primarily economic variables to explain Japanese inbound tourism from Korea. Over the course of their history, politically sensitive issues have arisen between Korean and Japan, such as the use of Korean ‘comfort women’ under Japanese colonial rule and the territorial dispute in the East Sea ( Lee et al., 2010 ). Korean public opinion (or sentiment) regarding these sensitive issues may affect Korean tourism to Japan. Future studies could consider this intangible aspect in modeling tourism demand between Korea and Japan. In addition, it would be interesting to test the effect of jet-fuel prices, our new proxy for transport cost, in different tourism destinations.

- Akis S. A compact econometric model of tourism demand for Turkey. Tourism Management. 1998; 19 (1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00097-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blake A., Sinclair M.T. Tourism crisis management: US response to September 11. Annals of Tourism Research. 2003; 30 (4):813–832. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00056-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blake A., Sinclair M.T., Soria J.A.C. Tourism productivity: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Annals of Tourism Research. 2006; 33 (4):1099–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowen J.T. Market segmentation in hospitality research: No longer a sequential process. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 1998; 10 (7):289–296. doi: 10.1108/09596119810240924. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowerman B.L., O’Connell R.T. PWS-Kent Publishing Company; MA: 1990. Linear statistical models: An applied approach. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burnham K.P., Anderson D.R. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods Research. 2004; 33 (2):261–304. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carey K. Estimation of Caribbean tourism demand: Issues in measurement and methodology. Atlantic Economic Journal. 1991; 19 (3):32–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavanaugh, J. E. (2012). Model selection: The Akaike information criterion . Retrieved from 〈 http://myweb.uiowa.edu/cavaaugh/ms_lec_2_ho.pdf 〉.

- Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (2015). Databases . Retrieved from 〈http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/en/bdd_modele/bdd.asp〉 .

- Chang, C. L., Khamkaew, T., & McAleer, M. (2010). Estimating price effects in an almost ideal demand model of outbound Thai tourism to East Asia . Retrieved from 〈 http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1587532 〉

- Chatziantoniou I., Filis G., Eeckels B., Apostolakis A. Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: A structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Management. 2013; 36 :331–341. [ Google Scholar ]

- Covington B., Thunberg E.M., Jauregui C. International demand for the United States as a travel destination. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 1995; 3 (4):39–50. doi: 10.1300/J073v03n04_03. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crouch G.I. The study of international tourism demand: A review of findings. Journal of Travel Research. 1994; 33 (1):12–23. doi: 10.1177/004728759403300102. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crouch G.I. A meta-analysis of tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 1995; 22 (1):103–118. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(94)00054-V. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vita G. The long-run impact of exchange rate regimes on international tourism flows. Tourism Management. 2014; 45 :226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Vita G., Kyaw K.S. Role of the exchange rate in tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 2013; 43 :624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.011. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dimanche F. The Louisiana tax free shopping program for international visitors: A case study. Journal of Travel Research. 2003; 41 (3):311–314. doi: 10.1177/0047287502239044. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Divisekera S. A model of demand for international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2003; 30 (1):31–49. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00029-4. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Di Matteo L., Di Matteo R. An analysis of Canadian cross-border travel. Annals of Tourism Research. 1996; 23 (1):103–122. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00038-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dritsakis N., Gialetaki K. Cointegration analysis of tourism revenues by the member countries of European Union to Greece. Tourism Analysis. 2004; 9 (3):179–186. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2004.11081452. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Durbarry R., Sinclair M.T. Market shares analysis: The case of French tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 2003; 30 (4):927–941. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00058-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L., Forsyth P., Rao P. The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: A comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management. 2000; 21 (1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00081-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L., Kim C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism. 2003; 6 (5):369–414. doi: 10.1080/13683500308667962. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edward A. Economist Intelligence Unit; London, UK: 1995. Asia-Pacific Travel Forecasts to 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eilat Y., Einav L. Determinants of international tourism: A three-dimensional panel data analysis. Applied Economics. 2004; 36 (12):1315–1327. doi: 10.1080/000368404000180897. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eryiğit M., Kotil E., Eryiğit R. Factors affecting international tourism flows to Turkey: A gravity model approach. Tourism Economics. 2010; 16 (3):585–595. doi: 10.5367/000000010792278374. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garín-Muñoz T. Inbound international tourism to Canary Islands: A dynamic panel data model. Tourism Management. 2006; 27 (2):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geweke J. The dynamic factor analysis of economic time series. In: Aigner D.J., Goldberger A.S., editors. Latent variables in socio-economic models. North Holland; Amsterdam: 1977. pp. 365–383. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gil-Pareja S., Llorca-Vivero R., Martínez-Serrano J.A. The impact of embassies and consulates on tourism. Tourism Management. 2007; 28 (2):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.016. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gould W., Rogers W. Summary of tests of normality. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1992; 1 :3. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gray H.P. The demand for international travel by the United States and Canada. International Economic Review. 1966; 7 (1):83–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffin R.K., Shea L., Weaver P. How business travelers discriminate between mid-priced and luxury hotels: An analysis using a longitudinal sample. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Marketing. 1997; 4 (2):63–75. doi: 10.1300/J150v04n02_05. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. 7th ed. Pearson Education; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2010. Multivariate data analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hiemstra S., Wong K.K. Factors affecting demand for tourism in Hong Kong. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 2002; 13 (1–2):41–60. doi: 10.1300/J073v13n01_04. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hui T.K., Yuen E.C.C. An econometric study on Japanese tourist arrivals in British Columbia and its implications. The Service Industries Journal. 1998; 18 (4):38–50. doi: 10.1080/02642069800000040. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Japan National Tourist Organization (2014). Tourism data . Retrieved from 〈 http://www.jnto.go.jp/jpn/reference/tourism_data/departure_trends/index.html 〉.

- Japan National Tourist Organization (2015). Trends of tourist arrivals . Retrieved from 〈 http://www.jnto.go.jp/jpn/reference/tourism_data/visitor_trends/index.html 〉.

- Japan Tourism Marketing (2015). Tourism statistics . Retrieved from 〈 http://www.tourism.jp/en/statistics/ 〉.

- Kliman M.L. A quantitative analysis of Canadian overseas tourism. Transportation Research Part A: General. 1981; 15 (6):487–497. doi: 10.1016/0191-2607(81)90116-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kulendran N., Witt S.F. Cointegration versus least squares regression. Annals of Tourism Research. 2001; 28 (2):291–311. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00031-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Law R., Goh C., Pine R. Modeling tourism demand: A decision rules based approach. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 2004; 16 (2–3):61–69. doi: 10.1300/J073v16n02_05. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C.K. Major determinants of international tourism demand for South Korea: Inclusion of marketing variable. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 1996; 5 (1–2):101–118. doi: 10.1300/J073v05n01_07. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C.K., Song H.J., Bendle L.J. The impact of visa-free entry on outbound tourism: A case study of South Korean travelers visiting Japan. Tourism Geographies. 2010; 12 (2):302–323. doi: 10.1080/14616681003727991. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C.K., Song H.J., Mjelde J.W. The forecasting of international Expo tourism using quantitative and qualitative techniques. Tourism Management. 2008; 29 (6):1084–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.007. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C.K., Var T., Blaine T.W. Determinants of inbound tourist expenditures. Annals of Tourism Research. 1996; 23 (3):527–542. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00073-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li G., Song H., Witt S.F. Recent developments in econometric modeling and forecasting. Journal of Travel Research. 2005; 44 (1):82–99. doi: 10.1177/0047287505276594. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim C. A meta analysis review of international tourism demand. Journal of Travel Research. 1999; 37 (3):273–284. doi: 10.1177/004728759903700309. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Loeb P.D. International travel to the United States: An econometric evaluation. Annals of Tourism Research. 1982; 9 (1):7–20. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(82)90031-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin C.A., Witt S.F. Substitute prices in models of tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research. 1988; 15 (2):255–268. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(88)90086-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McKehee N.G., Kim K. Motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. Journal of Travel Research. 2004; 43 (2):161–170. doi: 10.1177/0047287504268245. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morley C.L. The use of CPI for tourism prices in demand modelling. Tourism Management. 1994; 15 (5):342–346. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(94)90088-4. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muchapondwa E., Pimhidzai O. Modelling international tourism demand for Zimbabwe. International Journal of Business and Social Science. 2011; 2 (2):71–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson L.A., Dickey D.A., Smith J.M. Estimating time series and cross section tourism demand models: Mainland United States to Hawaii data. Tourism Management. 2011; 32 (1):28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.10.005. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Hagan J.W., Harrison M.J. Market shares of US tourist expenditure in Europe: An econometric analysis. Applied Economics. 1984; 16 (6):919–931. doi: 10.1080/00036848400000060. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ong, S. (2014). Japan market update: Abenomics 1 year on opportunities in tourism . International Enterprise Singapore. Retrieved from 〈 http://www.iesingapore.gov.sg 〉.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015). OECD statistics . Retrieved from 〈 http://stats.oecd.org/ 〉.

- Papadopoulos S.I. A conceptual tourism marketing planning model: Part 1. European Journal of Marketing. 1989; 23 (1):31–40. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000000539. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Park J.Y., Jang S. An extended gravity model: Applying destination competitiveness. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 2014; 31 (7):799–816. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2014.889640. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patsouratis V., Frangouli Z., Anastasopoulos G. Competition in tourism among the Mediterranean countries. Applied Economics. 2005; 37 (16):1865–1870. doi: 10.1080/00036840500217226. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peng G.B., Song H., Witt S.F. Demand modeling and forecasting. In: Dwyer L., Gill A., Seetaram N., editors. Handbook of research methods in tourism: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Edward Elgar Publishing; MA: 2012. pp. 71–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prideaux B. Factors affecting bilateral tourism flows. Annals of Tourism Research. 2005; 32 (3):780–801. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.008. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qu H., Lam S. A travel demand model for Mainland Chinese tourists to Hong Kong. Tourism Management. 1997; 18 (8):593–597. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00084-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Revelle, W. (2008). Point-biserial correlation . Retrieved from 〈 http://r.789695.n4.nabble.com/Point-biserial-correlation-td862060.html 〉.

- Roselló-Villalonga J., Aguiló-Pérez E., Riera A. Modelling tourism demand dynamics. Journal of Travel Research. 2005; 44 (1):111–116. doi: 10.1177/0047287505276602. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H., Li G. Tourism demand modeling and forecasting: A review of recent research. Tourism Management. 2008; 29 (2):203–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.016. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H., Turner L. Tourism demand forecasting. In: Dwyer L., Forsyth P., editors. International handbook on the economics of tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing; MA: 2006. pp. 89–114. [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H., Witt S.F. Routledge; UK: 2000. Tourism demand modelling and forecasting: Modern econometric approaches. [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H., Witt S.F. Forecasting international tourist flows to Macau. Tourism Management. 2006; 27 (2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.09.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H., Witt S.F., Li G. Routledge; London: 2009. The advanced econometrics of tourism demand. [ Google Scholar ]

- Statistics Korea (2015). Resources . Retrieved from 〈 http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/resources/1/index.static〉 .

- Stock J.H., Watson M.W. Dynamic factor models. In: Clements M.J., Hendry D.F., editors. Oxford Handbook on Economic Forecasting. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. pp. 35–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan A.Y., McCahon C., Miller J. Modeling tourist flows to Indonesia and Malaysia. Journal of Travel Tourism Marketing. 2002; 13 (1-2):61–82. doi: 10.1300/J073v13n01_05. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Tourism Organization (2014). Tourism highlights . Retrieved from 〈 http://mkt.unwto.org/publication/unwto-tourism-highlights-2014-editionWTO 〉.

- U.S. Department of Transportation (2015). Bureau of transportation statistics . Retrieved from 〈 http://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/airfares 〉.

- Uysal M., Crompton J.L. Determinants of demand for international tourist flows to Turkey. Tourism Management. 1984; 5 (4):288–297. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(84)90025-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uzama A. Marketing Japan’s travel and tourism industry to international tourists. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2009; 21 (3):356–365. doi: 10.1108/09596110910948341. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y.S. The impact of crisis events and macroeconomic activity on Taiwan’s international inbound tourism demand. Tourism Management. 2009; 30 (1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.010. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Webber K. Outdoor adventure tourism: A review of research approaches. Annals of Tourism Research. 2001; 28 (2):360–377. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00051-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Witt C.A., Witt S.F. Appraising an econometric forecasting model. Journal of Travel Research. 1990; 28 (3):30–34. doi: 10.1177/004728759002800305. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Witt S.F., Witt C.A. Forecasting tourism demand: A review of empirical research. International Journal of Forecasting. 1995; 11 (3):447–475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0619-2070(95)00591-7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yap, G. (2011). Modelling the spillover effects of exchange rates on Australia’s inbound tourism growth . Retrieved from 〈 http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1789645 〉.

Watch CBS News

Hotel prices soar as tourists flock to see solar eclipse

By Megan Cerullo

Edited By Anne Marie Lee

April 6, 2024 / 5:00 AM EDT / CBS News

Susan Hochman, who for seven years has been planning to travel to see the solar eclipse on April 8 , will be shelling out hundreds of dollars for a one-night stay at a modest hotel room in Saranac Lake, New York, which is in the path of the so-called totality .

She'll be spending $650 to spend one night at a Best Western hotel, where room rates are as low as $99 during less busy periods, according to hotel staff.

"I thought that was crazy," the New York City resident said. "I almost died at the $650 rate the Best Western quoted, but at least I can just stay there the one night that I need."

Hochman booked her accommodations in October of last year. Still, she wishes she had made reservations far earlier. "As much as I had given it forethought, I didn't plan as much in advance as I should have," she said. She called the inflated lodging prices "kooky crazy."

Initially, Hochman had planned to stay at the nearby Saranac Waterfront Lodge, a luxury resort on the lake, with friends. But at $700 a night, with a two-night minimum, the hotel was out of her budget.

The cost for a room with two queen beds and a view of the lake? $2,400. The room rate drops to $1,100 on April 8 on the day of the eclipse, according to the hotel, which added that guests started booking rooms there a year ago.

By contrast, the following night, April 9, the same room costs $131, while on April 15 room rates drop to $111.

The Hampton Inn in Carbondale, Illinois, also situated in the solar eclipse's path , doesn't have any rooms available on either April 7 or 8.

"We've been sold out for months now," the hotel said. A revenue management team sets the hotel's rates, which a spokesperson said "are much higher than usual" for the April event.

$1 billion boost

Eclipse-related tourism could pump as much as $1 billion into local economies. All along the roughly 115-mile-wide stretch of land from Texas to Maine, from where the moon's full blocking of the sun will be momentarily visible, towns are expecting a spike in business as hordes of sky-gazing tourists spend on everything from lodging and dining to souvenirs .

Other types of accommodations, like homes on Airbnb, are also in high demand. There has been a 1,000% increase in searches for stays along the path of totality, according to the home-sharing platform.

Vacasa, another vacation rental management company, told CBS MoneyWatch that tourists appear most eager to watch the eclipse from the state of Texas, based on searches for homes on its site. Vermont is the second most popular destination, followed by Maine.

Average daily rates for homes in Burlington, Vermont, are $506. In Dallas, they're $375.

Airline ticket prices are up, too. The average flight price to Dallas-Fort Worth, landing on April 7, is $1,900, according to travel site Hopper.

For last-minute travelers eager to see the eclipse, Hopper lead economist Hayley Berg offered advice for saving money.

"Consider staying at hotels outside of the path of totality and driving into the path in the afternoon on Monday," she told CBS News. "That way you'll pay a lower rate but can still experience the eclipse."

Kayak, another travel platform, has launched a tool that lets people search for the lowest-cost hotel destinations on the eclipse's path of totality. According to Kayak, hotels are cheapest, on average, in Montreal, Canada, which is also a path city . The best rental car deals on average can also be found in Montreal.

Megan Cerullo is a New York-based reporter for CBS MoneyWatch covering small business, workplace, health care, consumer spending and personal finance topics. She regularly appears on CBS News Streaming to discuss her reporting.

More from CBS News

Why you should add gold to your retirement plan now

Here's how much Caitlin Clark will make in the WNBA

Here's how much you'd save by using a home equity loan

CDs vs. high-yield savings accounts: What to consider before the Fed cuts rates

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Industry-specific and extensively researched technical data (partially from exclusive partnerships). A paid subscription is required for full access.

- Change in the travel price index vs. consumer price index in the U.S. 2022-2023

The travel price index (TPI) published by the U.S. Travel Association includes data on the monthly changes in the consumer price index (CPI) of travel and tourism services in the United States, such as airline fares, lodging, and recreation. Throughout 2022, and particularly in the first half of the year, both the travel and consumer price indexes grew dramatically, with the TPI reporting a staggering 19.4 percent annual increase in May. Meanwhile, in December 2023, the TPI went up by 1.3 percent compared to the previous year, while the CPI experienced a 3.3 percent year-over-year rise.

Year-over-year percentage change in the travel price index vs. consumer price index in the United States from January 2022 to December 2023

- Immediate access to 1m+ statistics

- Incl. source references

- Download as PNG, PDF, XLS, PPT

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

January 2024

United States

January 2022 to December 2023

non-seasonally adjusted figures

The travel price index refers to the following industries: transportation (airline fares, motor fuel, intracity transportation, intercity transportation); lodging (hotels/motels); recreation; food and beverage (alcohol away from home, food away from home). Data prior to December 2023 were previously published by the source. Figures for November 2023 were not available.

Other statistics on the topic Impact of inflation on travel and tourism worldwide

Accommodation

- HICP inflation rate for hotels and similar accommodation in the EU 2017-2024

- CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2023

- HICP inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the EU 2024

Leisure Travel

- Britons' main responses to the impact of cost of living on vacations 2023

To download this statistic in XLS format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PNG format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PDF format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PPT format you need a Statista Account

As a Premium user you get access to the detailed source references and background information about this statistic.

As a Premium user you get access to background information and details about the release of this statistic.

As soon as this statistic is updated, you will immediately be notified via e-mail.

… to incorporate the statistic into your presentation at any time.

You need at least a Starter Account to use this feature.

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics. This statistic is not included in your account.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Statistics on " Impact of inflation on travel and tourism worldwide "

- Change in the travel price index in the U.S. December 2023, by industry

- Impact of high prices on travel plans in the U.S. 2023

- Share of U.S. travelers changing their holiday plans due to inflation 2023, by income

- Consumers who spent less on travel and dining out in the U.S. 2023, by income

- Annual average HICP of travel and tourism services in the EU 2019-2023

- HICP inflation rate for restaurants and cafés in the EU 2017-2024

- Europeans' main concerns about trips within Europe 2023

- European travelers most concerned with rising travel costs 2023, by country

- Share of Europeans believing that inflation impacted the desire to travel 2023

- Reasons to not travel long-haul to Europe worldwide 2023, by country

- Annual average CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2019-2023

- Main barriers to taking overnight domestic trips among adults in the UK 2023

- Share of Britons thinking that cost of living might impact holiday plans 2023, by age

- Main issues for business travel according to travel suppliers worldwide 2024

- Main issues for business travel according to travel managers worldwide 2024

- Main issues for business travel worldwide 2024, by region

Other statistics that may interest you Impact of inflation on travel and tourism worldwide

Impact on travel in the United States

- Premium Statistic Change in the travel price index vs. consumer price index in the U.S. 2022-2023

- Premium Statistic Change in the travel price index in the U.S. December 2023, by industry

- Premium Statistic Impact of high prices on travel plans in the U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of U.S. travelers changing their holiday plans due to inflation 2023, by income

- Premium Statistic Consumers who spent less on travel and dining out in the U.S. 2023, by income

Impact on travel in Europe

- Basic Statistic Annual average HICP of travel and tourism services in the EU 2019-2023

- Basic Statistic HICP inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the EU 2024

- Basic Statistic HICP inflation rate for restaurants and cafés in the EU 2017-2024

- Basic Statistic HICP inflation rate for hotels and similar accommodation in the EU 2017-2024

- Premium Statistic Europeans' main concerns about trips within Europe 2023

- Premium Statistic European travelers most concerned with rising travel costs 2023, by country

- Premium Statistic Share of Europeans believing that inflation impacted the desire to travel 2023

- Premium Statistic Reasons to not travel long-haul to Europe worldwide 2023, by country

Impact on travel in the United Kingdom

- Premium Statistic Annual average CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2019-2023

- Premium Statistic CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Main barriers to taking overnight domestic trips among adults in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of Britons thinking that cost of living might impact holiday plans 2023, by age

- Premium Statistic Britons' main responses to the impact of cost of living on vacations 2023

Impact on global business travel

- Premium Statistic Main issues for business travel according to travel suppliers worldwide 2024

- Premium Statistic Main issues for business travel according to travel managers worldwide 2024

- Premium Statistic Main issues for business travel worldwide 2024, by region

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

Elasticity, demand and supply, tourism

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2015

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Jaume Rosselló 3

932 Accesses

2 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Crouch, G. 1992 Effect of Income and Price on International Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 19:643-664.

Article Google Scholar

Crouch, G. 1994 The Study of International Tourism: A Survey of Practice. Journal of Travel Research 32(4):41-55.

Li, G., H. Song, and S. Witt 2005 Recent Developments in Econometric Modeling and Forecasting. Journal of Travel Research 44:82-99.

Lim, C. 1999 A Meta-Analytic Review of International Tourism Demand. Journal of Travel Research 37:273-284.

Rosselló, J. 2012 Regression Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Tourism, L. Dwyer, A. Gill and N. Seetaram, eds., pp.31-46. Cheltenman: Edward Elgar.

Google Scholar

Song, H., S. Witt, and G. Li 2009 The Advanced Econometrics of Tourism Demand. London: Routledge.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departament d’Economia Aplicada, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Carretera de Valldemossa, 7.5km, 07122, Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Jaume Rosselló

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jaume Rosselló .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Hospitality Leadership, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, Wisconsin, USA

Jafar Jafari

School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Honggen Xiao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Rosselló, J. (2015). Elasticity, demand and supply, tourism. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_67-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_67-1

Received : 24 April 2015

Accepted : 24 April 2015

Published : 24 September 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subscribe Digital Print

- Semiconductors

- Latest News

- Deep Dive Podcast

Today's print edition

Home Delivery

- Crime & Legal

- Science & Health

- More sports

- CLIMATE CHANGE

- SUSTAINABILITY

- EARTH SCIENCE

- Food & Drink

- Style & Design

- TV & Streaming

- Entertainment news

Japan hotel prices near 30-year high as weak yen lures record tourists

Hotel prices in Japan soared to a near three-decade high in March, as the cheap yen and the cherry blossom season attracted a record number of tourists to the country.

A record 3.1 million people visited Japan in March. The yen is hovering at a 34-year low against the dollar, making the country an attractive destination for inbound tourists. The tourism boom has been led by arrivals from South Korea, Taiwan and China in the midst of the cherry blossom season, which traditionally draws in visitors.

Contributing to the spike in hotel prices is a labor shortage in Japan, according to Harumi Taguchi, principal economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"To be able to cover the high occupancy rates with the labor shortage, the hotel rates have to be increased,” she said. "The demand is high from inbound tourists, so it’s an environment where it’s easy to raise the prices.”

The weakening yen has also spurred spending by holidaymakers. Foreign visitors spent ¥1.75 trillion in the January to March period, an increase of 52% from 2019, according to data from the Japan Tourist Agency. Shoppers have been snapping up luxury goods at discounted prices as well.

"Should demand from foreign visitors continue to increase, hotel prices may just keep going up,” said Taguchi. "And with the weak yen, it’s still cheap for foreigners to pay that price.”

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

Space Tourism: Can A Civilian Go To Space?

2021 has been a busy year for private space tourism: overall, more than 15 civilians took a trip to space during this year. In this article, you will learn more about the space tourism industry, its history, and the companies that are most likely to make you a space tourist.

What is space tourism?

Brief history of space tourism, space tourism companies, orbital and suborbital space flights, how much does it cost for a person to go to space, is space tourism worth it, can i become a space tourist, why is space tourism bad for the environment.

Space tourism is human space travel for recreational or leisure purposes . It’s divided into different types, including orbital, suborbital, and lunar space tourism.