- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Hippy dream or total nightmare? The untold story of Isle of Wight 1970

50 years ago this week, the Hendrix-headlined festival rocked a reported 600,000, but the fallout affected how music events would be run forever. Now a more positive story is emerging

S hortly before the infamous 1970 Isle of Wight festival , Stanley Dunmore, a local public health inspector, worried about “a possible breakdown of public order … if the festival is a failure, or falls short of expectations, or the weather is bad, or facilities which the fans expect to find in the town are not available”.

His observations, made when music festivals were in their infancy, confirm some things that we know about them today – if only Billy McFarland and Ja Rule had read Dunmore’s report before the spectacular failure of Fyre festival . These events are complex and expensive to coordinate, especially in remote settings with inebriated and underprepared crowds cowed by the weather. If things go wrong, disaster can ensue.

Isle of Wight 1970 became the British festival that we associate with disaster. The myth goes that a group of young men, out to make a few quid from youthful music fans, put on the largest-ever pop festival in Britain at the time. To protect their investment and rake in gate receipts, they erected fencing around the site to contain the crowd of 600,000 and exclude troublemakers. Building on a few references in the press, the popular image is of radicals and French anarchists flooding down from Desolation Hill, which overlooked the festival site, and ripping down the fencing. In a recent article on Joni Mitchell’s performance, the Guardian reported that “fights broke out, objects were thrown, and a lot of bad acid was taken”.

But it is easy to get the wrong impression about the 1970 festival. It has been mythologised and attacked for personal and political reasons, but against most criteria other than finances (a £40,000-£60,000 loss), the evidence that I unearthed for my first book reveals a beguiling and misunderstood story. It suggests the festival was not as bad as it seems – in fact, at the time some saw it as the British Woodstock.

The first Isle of Wight festival, in 1968, attracted about 8,000 festivalgoers to Hell Field near Godshill. Three Labour-supporting brothers in their early 20s brought to the island from Derbyshire during childhood, Ray, Bill and Ronald Foulk, instigated the festival to raise funds to build a municipal indoor swimming pool.

The 1969 festival exceeded their wildest expectations. Bob Dylan , who had hardly played live since his motorbike accident in 1966, attracted the world’s media and 80,000 to 100,000 festivalgoers. Ray Foulk says the 1969 festival was not without hiccups – he told me that “the catering was not adequate; we were ripped off and the public were”, and a lack of toilets led to long queues. But the promoters learned on their feet and overcame these problems; good weather did not test the amenities at the site, now in Wootton. There was a headline performance from the Who , and Dylan’s appearance was a culturally significant moment – a pilgrimage – for the postwar generation.

It teed up the 1970 festival, one of the largest outdoor gatherings in Britain since the war, even if the figure of 600,000 is probably an overestimate. The event might not have taken place if local councillors, well-connected islanders and their Conservative MP, Mark Woodnutt, had had their way. In letters to the environment department, Woodnutt argued that the festival could cause a polio epidemic (the island had suffered one in 1949) and that the 1969 festival had “left a scene of indescribable filth”. However, he would need a high court injunction to stop the festival, and proof that the festival was a threat to public and environmental health rather than simply a nuisance.

Mindful of a a possible injunction, the Foulks’ company Fiery Creations reminded the council of the lack of trouble during the 1969 festival and the good publicity the island received because of the event. Dunmore, the health inspector, and Douglas Quantrill, the island’s chief medical officer, alleviated sanitation and safety fears, and helped coordinate organisations from macrobiotic caterers to National Rail.

Without legal recourse, local pressure groups and councillors disingenuously claimed the island lacked suitable sites for a large festival and pressured landowners into refusing to rent land. The East Afton site was only agreed in early August, weeks before the festival opened at the start of the bank holiday. The valley, flanked by a hill on National Trust property and near idyllic beaches below white cliffs, would soon host a stage, 20 turnstiles, 66 food and drink stalls, 500 toilets and 600 feet of urinals.

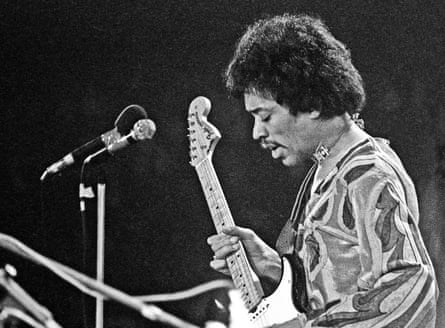

Reports from the time, and footage, suggest that the crowd witnessed some stunning performances. The lineup included the Who, Miles Davis, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, the Moody Blues, Jethro Tull, Sly and the Family Stone and Gilberto Gil; Jimi Hendrix played one of his last performances before his death. Recently rediscovered photographs taken by Peter Bull show calm and content festivalgoers, who resemble their contemporary counterparts aside from their attire, lack of mobile phones and the fact that they’re nearly all sitting down.

There were disturbances, though. A group, no more than 200 of those camping on Desolation Hill, attempted to break down the perimeter wall the day before the festival began. Later, on Sunday morning, organisers and audience argued when security cleared the inner arena for Jethro Tull’s soundcheck and to check tickets. At 4pm on Sunday afternoon, MC Rikki Farr declared the festival free (to the horror of Ray Foulk who was standing in the crowd) and, after the announcement, the inner arena wall was dismantled from the inside by ticket holders, prompting a queue of concerned workers and creditors seeking immediate payment backstage. There were 117 arrests for possession of drugs.

Conflicts do not feature prominently in the official record, however. Douglas Osmond, the chief constable of Hampshire police, dressed up like a hippy and went incognito on Desolation Hill for a day. He claimed to see less violence than at a typical football match and concluded that “people become unduly anxious about these gatherings”.

Every national newspaper reported on the festival, with some of them, glad for news in August, printing extensive coverage. These generally positive reports were punctuated by scurrilous stories about sex and drugs, outraged locals and photographs of nude (mostly female) bodies. The Sunday Mirror’s account explained: “This isn’t quite paradise. But if you are young and can look after yourself and the sun stays out and the music stays loud, it doesn’t matter.”

It is interesting, then, that a view of the festival as a disaster has come to dominate. Organisers blame the late documentary film-maker Murray Lerner. Fiery Creations and Lerner wanted to emulate the success of the 1970 Woodstock documentary, which took just under $50m at the US box office, but their Isle of Wight film did not find a distributor until 1997 and the delay caused acrimony. Ray Foulk, particularly in the second volume of his book When the World Came to the Isle of Wight, and Peter Harrigan, Fiery Creations’ publicist, allege that Lerner removed footage of isolated incidents of trouble from their context and spliced them between performances for drama. For instance, Lerner’s documentary edited the footage of arguments in the main arena on Sunday morning to include shots of some drunken jeering and stray beers thrown at a lighting tower. The film exaggerates the intensity, significance and extent of either disturbance. It was, Foulk said, “complete fakery” and “besmirched not just the festival but a whole generation of people”. Indeed, he argues that the festival was only declared free to benefit Lerner’s documentary in the first place.

The organisers also made the mistake of inviting International Times (IT), a London-based countercultural paper, to view the site under construction. As head of the British White Panthers, its editor, Mick Farren, published communiques in pamphlets and IT that encouraged resistance. He saw the increased price (to £3, about the price of a double album) and security as an affront to his left-libertarian view that music festivals should be free, and claimed that the fences, security dogs and turnstiles evoked prison camps.

After losing £6,000 on their own free festival a month before, Phun City near Worthing, the 1970 Isle of Wight festival provided Farren and his peers a chance for some agitprop myth-making to champion the radical underground. Take Jean-Jacques Lebel, the only one of the “French anarchists” that can be identified from the festival despite that phrase recurring in several accounts – thanks to his involvement in the counterculture, Lebel could amplify his role in the festival’s mythology and its political significance through the underground press.

Farren’s fear about repression and exploitation were not misplaced, but misdirected. The idea that festivals had radical potential, alongside stigma concerning festivalgoers’ propriety, took hold, and exacerbated the anxieties and prejudices of conservative Isle of Wight residents. The county council had received calls to stop pop festivals since 1969 – one letter described festivalgoers as “social parasites” – and following the 1970 event Woodnutt introduced legislation to prevent another festival on the island. The council now had complete discretion over licenses for overnight events with a crowd over 5,000, and organisers would have to give four months’ notice. Subsequently, there were no further festivals there there until 2002.

Other rural areas wanted similar control and Conservative MP Jerry Wiggin’s Night Assemblies Bill offered it. The bill proposed criminalising any outdoor gathering of 1,000 people or more between midnight and 6am unless the organisers applied to a local authority at least four months before and provided financial guarantees.

The bill did not, however, define the “pop festival” clearly and therefore threatened the right to free assembly. The National Council for Civil Liberties argued it would “stifle political opinion and prevent activity at a time when too much emphasis is being put upon law and order at the expense of justice and liberty”, and the bill failed.

It exposed, though, tension between young people, the counterculture and rural British conservatism. The vitriol aimed at pop festivals, and the types of social change that they were seen to represent, is startling. Great Western festivals ran into to trouble, for instance, in Tollesbury, Essex, in 1972 when trying to find a festival site (it ultimately settled on Bardney, Lincolnshire). The local villagers burned effigies of the organisers, Lord Harlech and the actor Stanley Baker – the type of hip capitalists that countercultural radicals also feared. A local explained that this was because the festival would cause the “sheer rape of our way of life”. The panic over festivals became a trope for bored reporters in the summertime and justification for heavy-handed policing, as those brutally attacked by Thames Valley police at the Windsor free festival in 1974 will attest.

Quantrill, meanwhile, became a public health celebrity, if there is such a thing. Councils sought him out for advice on festivals and at the Royal Society of Health Symposium in 1971 he argued, in what became a widely circulated paper, that there was little risk in a reasonably well-planned festival such as the Isle of Wight 1970. The government select committee issued an official code of practice to guide local authorities and festival organisers, undermining “anarchic” or free festivals by giving local authorities clearer grounds for injunctions if a festival did not meet the code’s expensive recommendations. Without significant capital and a willing council, it made it harder for enthusiastic amateurs such as Fiery Creations to run a festival, leaving rural landowners and posh hipsters increasingly in charge.

When you attend the modern-day music festival, however, you are, in a sense, stepping into a world made by three brothers, their friends and a handful of kindly civil servants. Think of them when you find an empty, mercifully unstained Portaloo.

- Isle of Wight festival

- The music essay

- Music festivals

- Jimi Hendrix

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Anarchists, fire and rock'n'roll: the ultimate guide to the 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival

They thought the 1970 Isle Of Wight festival was going to be several days of peace, love and music – just like Woodstock the previous year. They thought wrong

You could make a valid argument that the 60s were all about trying to change the world, while the 70s were centred around the individual. Perhaps Jim Morrison summed it up best while performing with The Doors at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970: “We want the world… and we want it now!”

“A huge crowd – potentially dangerous,” filmmaker Murray Lerner recalls of the event. “A lot of hassle between the songs, but when the songs came, things quietened down. And some great classic rock performances, like The Who , Jimi Hendrix and The Doors. Joni Mitchell was great, and Miles Davis, of course.”

People heckling the performers, fans breaking down fences and entering free of charge, anarchists disrupting the proceedings, a fire over the stage, and festival organisers being in well over their heads were just some of the ‘highlights’ of Isle of Wight 1970.

As a result, there wouldn’t be another festival on this tiny island off the south coast of England for quite a while. Another 32 years, in fact.

The first Isle of Wight Festival took place in 1968, supposedly when the island’s swimming pool association needed to raise money, and the idea of holding a pop event sounded like a splendid idea. The 150-acre Hayles Field (dubbed Hell’s Field) was secured, and over two days 10,000 people saw performances by The Move, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Jefferson Airplane and Arthur Brown , among others. The festival was such a success that its organisers – the Foulks brothers, Ray, Ron and Bill, together with Rikki Farr – decided to stage another one.

With the organisers having convinced Bob Dylan to come out of exile to play his first show in years, and with The Who, The Moody Blues and The Band also on the bill, 1969’s three-day Isle of Wight Festival attracted a huge crowd of 100,000, with members of The Rolling Stones , The Beatles and Pink Floyd among the VIPs.

Even though the second show had been massively bigger than the first, no one could have predicted the number of people who would turn up in 1970, when the festival took place over five days and featured some of the biggest names in rock, including Jimi Hendrix, The Doors and The Who.

Classic Rock Newsletter

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Expecting a bigger audience still, a new festival site was scouted and the organisers settled on Afton Farm. But there was a problem – it was overlooked by Afton Down, a hill that offered a perfect view of the stage. It was obvious that thousands would congregate and camp out on the hill rather than pay to get in, but the site was chosen regardless.

Murray Lerner had directed the 1967 movie Festival!, which chronicled the highlights from several years of the Newport Folk Festival in the US – including Bob Dylan’s first-ever ‘electric’ performance.

By 1970 Lerner was ready to document another outdoor music spectacle on film, and he hooked up with the Isle of Wight Festival. Almost immediately after filming began, Lerner detected an unexpected ‘vibe’ surrounding the event. “I think that whole movement began to break apart,” he said.

“The kids got upset about the commercialisation that was going on. When you get a crowd of that many people, and one guy starts: ‘Let’s get in for nothing,’ there’s a ripple effect. So they all wanted to get in for free by smashing the fences.”

Lerner also recalled that there was “a lot of trouble in terms of the crowd. There were no fatalities [yet]. There was the fire, which we show [in the film]. It was just a guy who was told two weeks earlier to schedule fireworks. And without thinking, he shot them off, and everyone thought, ‘Okay, the stage is being attacked by flame’ [laughs]. I thought that was it.” Luckily the fire was soon under control.

The first two days of the 1970 event – August 26 and 27 (a Wednesday and a Thursday) – saw performances by mostly newer artists, including up-and-comers Supertramp and Terry Reid .

But it was another relative unknown who left a big impression on Lerner: “David Bromberg received a phenomenal reception from the audience. When he got off the stage he said: ‘I’m a star!’ You would’ve thought that Bromberg was going to be the biggest star in the world that night. I think he had four encores.”

On the Friday, by which time the attendance was reaching its peak (said to be 600,000), US band Chicago put in one of the first really outstanding displays of the festival. Although years later they became known as pop balladeers, back then were a jazz-infused powerhouse rock band with a blazing horn section that set them apart from the pack.

Chicago’s sax player, Walter Parazaider, recalls the events leading up to their set: “They had us in a holding area, with cottages and everything, which was just spectacular. The weather was great. Isle of Wight was our first experience of [playing festivals]. And you talk about people being really young – eyes as big as silver dollars, and taking everything in.

“The whole spectacle of it was amazing. It was massive. When you get that amount of people, just a whisper from a crowd is a roar. If you don’t keep within yourself, you could just as easily throw your horn in the crowd and run around like a lunatic, just freaking out.”

But Parazaider and the rest of Chicago needn’t have worried. “The crowd was very receptive,” he remembers. “That first album [1969’s Chicago Transit Authority ] had I’m A Man on it – a Spencer Davis Group tune – and it had gone over quite well in England. They knew the material, and we were quite well received. It was one of the highlights of our career. It was a knockout.”

Procol Harum and The Voices Of East Harlem played later the same day, before headliners Cactus closed the Friday with a hard rockin’ set. Cactus drummer Carmine Appice recalls that the festival’s main attraction, Jimi Hendrix, had turned up early.

“The thing that I remember the most is the fact that we were hanging out a lot backstage with Hendrix,” Appice says. “Everybody had little areas where they hung out. I remember a lot of jamming going on, with guitars and lots of banging on tabletops. At these festivals there was always a lot of drugs. We used to drink a sip of wine backstage, and you didn’t know – sometimes it would have mescaline in it or something weird. Everybody was smoking pot.

“It was cold, it was rainy. I think it was damp and foggy. I think the Isle of Wight was a bit of a disaster. That was the drag of being a headliner of those kind of festivals – by the time you go on it’s like the wee hours of the morning and your audience is going away. Look at Hendrix playing Woodstock – he had nobody there. Whereas Santana played when the place was packed.”

We used to drink a sip of wine backstage, and you didn’t know – sometimes it would have mescaline in it or something weird. Carmine Appice, Cactus

Saturday, August 29, had the most acts during a single day, with 12 very varied performers. Perhaps it was too varied. With most of the huge crowd geared up to rock to the likes of Hendrix, The Who and The Doors, when folk singer Joni Mitchell hit the stage early, trouble was brewing. A clearly ‘out of it’ guy who had got up on stage uninvited was forcibly removed. The crowd voiced their disapproval.

Murray Lerner: “There was a famous scene where the crowd was yelling and keeping her [Joni] from singing. She decided to face-down the crowd, and was playing the piano, vamping, and almost crying. [Joni] said to the crowd: ‘We’ve put our lives into this stuff. You’re acting like tourists.’ That changed the whole tone of it. She called the crowd ‘the beast’ and she decided to face them down. She had had problems with other places and had given in. But she decided in this case not to.

“I would say it was always on tenterhooks,” Lerner continued. “Was the crowd going to rush the stage? If they did, that would be the end. I was always worried about that, but they never did. It was really frightening when Joni was on. It’s hard to imagine when you have that many people in front of you, I can tell you that. I was always worried, because I didn’t understand what a crowd was until that festival. Then I realised there is nothing you can do – if the crowd moves, than it’s the end. You saw it in the Cincinnati thing [when fans were crushed to death trying to get into a Who concert in 1979].”

Although Lerner pointed out that Mitchell had earned the crowd’s respect by the end of her set, their hostility prevented what could have been a festival highlight.

According to the book The Visual Documentary by John Robertson, Neil Young was going to duet with Joni but changed his mind after witnessing the friction. Young left the festival before the end of Joni’s set.

With the crowd on edge, following Joni with Tiny Tim – an oddball bloke best-known for strumming a ukulele and singing in a warbling, irritating falsetto – might not have been a particularly good idea. But… “The audience went wild for Tiny Tim!” Lerner said. “Because it was like a campy reaction. You would have thought he was the biggest star in the world.”

Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull (who played the following evening) remembers Tiny Tim at the Isle of Wight for a different reason: “I’ll always remember Tiny Tim refusing to go on stage until he had the money in cash in a briefcase, at his feet. Not exactly in the spirit of the age.”

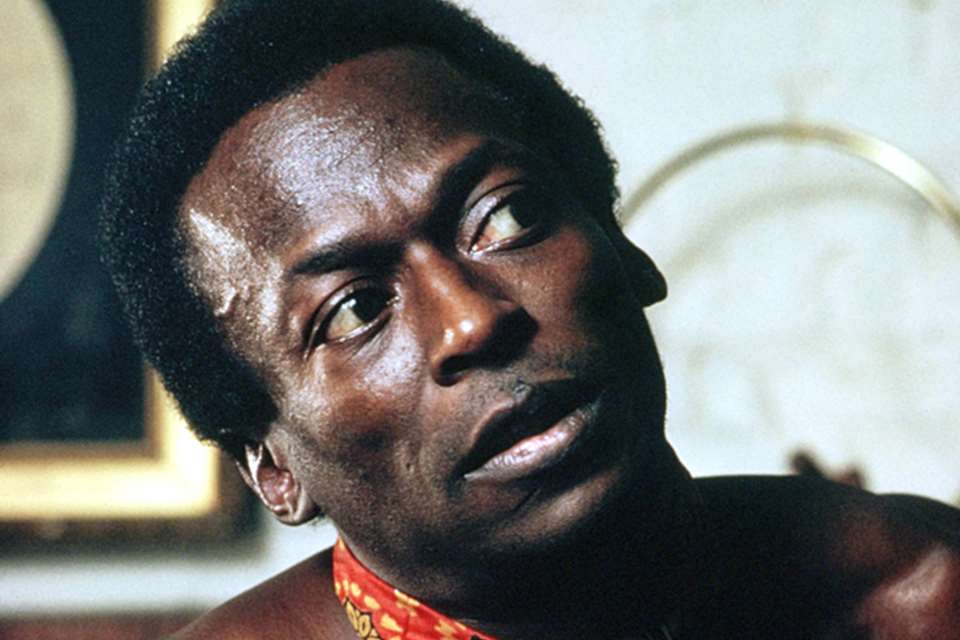

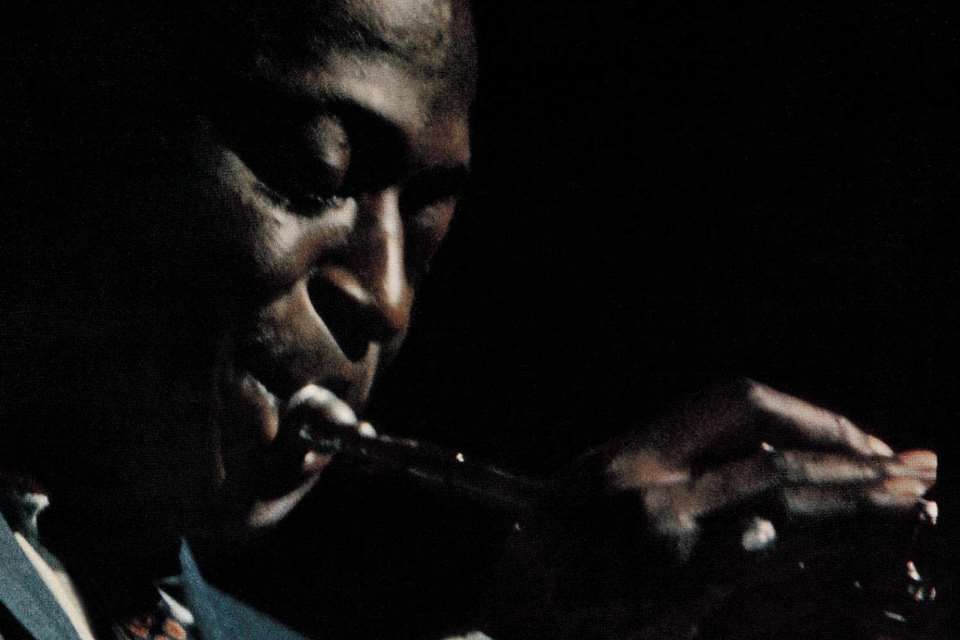

With the crowd now mellowing, legendary jazz trumpeter Miles Davis – in the midst of his groundbreaking jazz-fusion period – had the crowd in the palm of his hand.

"Miles Davis was a surprise – and really unusual. It was a revelation,” Lerner said. “The crowd really liked it. He went on, played, waved his hand at that audience and walked off. He played for approximately 38 minutes straight, without stopping.”

After some much-needed good-time blues rock from Ten Years After , the newly formed Emerson, Lake And Palmer played what was only their second-ever gig.

“The enduring memory is the actual physical sight of that many people,” ELP singer/bassist Greg Lake recalled of Isle of Wight 1970. “I suppose before that, the only other time you’d see that many people gathered together would have been a war. The night before, we’d played to something like 1,000 people. The next day it was 600,000.”

Lake also remembers that the festival didn’t exactly reflect the peace and love vibe that had characterised Woodstock.

“There was a kind of random chaos taking place. In a way, it was all meant to be relaxed and ‘peace, love and have a nice day’, but there was kind of a tension about the whole thing.”

Despite the lack of good vibes, ELP went down well with the crowd, perhaps because with their keyboards-heavy sound and classical leanings they delivered something a bit different. The band did have one dodgy moment, however, but managed to avoid an explosive – literally – situation that could have been disastrous.

“We decided to fire these 19th-century cannons at the end of Pictures At An Exhibition – to emulate the 1812 Overture,” Lake explains. “Unknown to us, the road crew had doubled the charge in the cannons. All I can remember was seeing this huge, solid-iron cannon leave the ground! It blew a couple of people off the stage. Luckily there was no cannonball in it. Thank God!”

In a similar way that Santana’s electrifying performance at Woodstock catapulted the then-unknown band to overnight stardom, ELP’s show-stealing performance at Isle of Wight gave the newly formed supergroup a huge career boost.

“After that festival, the very next day ELP was on the front page of every music newspaper,” Lake remembered. “It was indeed one of those overnight sensations.” After ELP and their cannons, next up came one of the festival’s big guns – The Doors. Then in the midst of singer Jim Morrison’s Miami trial (for allegedly exposing himself on stage), the band had been granted permission to leave the US briefly to perform at the festival.

Lerner recalled: “ Jim Morrison said to me: ‘I don’t think you’re going to get an image, because our lights are low. We’re not going to change it.’ But in fact I got some beautiful images by looking into the light and making it look surrealistic and abstract.

“The Doors were hypnotic but they had to leave right after their performance – they were on trial in Miami. They were let out just for that performance. So they had to leave right away.”

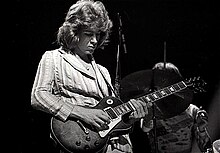

If the crowd had been hypnotised by The Doors, they were walloped back to their senses by The Who. Still plugging their Tommy album, Pete Townshend and co put in a stellar performance that is now considered a career high point for the band.

“The Who’s performance was really fantastic,” Lerner enthused. “A great, theatrical presentation, with huge spotlights behind them that dazzled you. The ending of Tommy was really incredible. And Naked Eye was great.”

“And of course, Keith Moon was fantastic – playing around and having fun. He was in good shape while he was playing. I don’t know what happened afterwards [laughs].”

If the promoters were indeed attempting to model the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival after Woodstock, this was the night that it became quite evident, as three Woodstock veterans closed the evening’s entertainment: The Who, hippy-dippy folk songstress Melanie and US funksters Sly And The Family Stone. The latter were by now one of the world’s top acts, mixing social commentary in songs that appealed to both rock and dance fans.

Family Stone sax player Jerry Martini recalls that the fans were receptive to his band. “It was good. I just remember us playing our concert, going over well, and having a great time at the nightclub they had there – it was jam-packed. I remember leaving that with a good feeling.”

While Sly And The Family Stone’s performance at the Isle of Wight went off without a hitch, Martini admits that it wasn’t quite as magical as a certain previous performance. “I don’t think it was as good as Woodstock for us. Woodstock did the most for us, but it was way up there.”

Sunday, August 30 was the final full day of performances, featuring the man who many considered to be the absolute headliner of the whole festival: Jimi Hendrix. In the morning, an ill-advised attempt was made to clear out the huge number of people who’d gathered for Jethro Tull’s soundcheck, to ensure that those without a five-day ticket would have to pay.

Lerner: “The attempt to empty the arena was really funny. It was impossible. They said: ‘They’re not going to do a soundcheck unless you leave. Then [Tull manager] Terry Ellis said: ‘Don’t tell them that, because we don’t care if they’re here.’

“They tried all sorts of things to try to get rid of the people, but they couldn’t. They were saying stupid things. And they thought the radicals were French, so the announcer said: ‘Does anyone speak French?’ This girl came, and spoke French very crudely, so the whole crowd was sniggering. She said: ‘Those who have tickets, burn your tickets, and then we’ll know you have a ticket.’ It was stupid. You’re talking about 100,000 people. They weren’t going to leave easily.”

Soon the crowd was throwing debris at the stage.

It was around this time that a van full of young hopefuls pulled up to the festival site. It was space rockers Hawkwind , who asked if they could play an impromptu set. The organisers said they could – but outside the festival perimeter.

Hawkwind leader Dave Brock remembers the day well: “What you’ve got to remember is the Isle of Wight has some lovely chalk cliffs. But the actual festival itself had all of these big corrugated sheets, like a prison camp. Outside the festival there was this big canvas city, at the centre of which was this gigantic inflatable tent. It had a generator running it, and the whole thing gradually inflated up. But then the generator ran out, and the tent started sinking down!

“Jimi Hendrix came in to see what was going on. Our saxophonist [Nik Turner] had his face halfpainted silver. I think in Hendrix’s set Jimi dedicated one of the numbers to ‘the guy down in the front with a silver face’, which was Nik. Nik got around to talking to him and asked him if he’d have a jam with us. But by the time he got there the tent was deflating and people were all standing with their hands up trying to support it – it was about eight foot high.”

Brock also recalls drugs being passed around freely: “We all took loads of LSD. Our lead guitarist, Huey [Huw Lloyd Langton], freaked out badly. He’d been spiked up on some orange juice. Unfortunately I had some as well. Suddenly I had this great rush come over me – I was all tingly and peculiar. I had this lady with me, who took me away up to the cliff tops for a walk to try and calm me down.”

And then there was the bedlam going on outside the gates. “There were a lot of anarchists,” Brock says. “They were all saying that when the festival has made enough money, then the fences should be destroyed. They started ripping the fences down. People threatening each other and all that. There were about 10,000 people outside.”

Back inside the festival, an early standout performance of the final day was that of Free , who were supporting their now classic Fire And Water album.

Murray Lerner was just one of many who was knocked out by the British blues rockers. “To me they were a revelation,” he enthuses. “I had never heard them before. I thought they were fantastic – their energy, their sensibility. And All Right Now to me was really a thrilling song.”

Soon after Free’s set, another British band also impressed Lerner – The Moody Blues:

“It was at twilight, and the lighting was unusual. I liked the singing – it was more melodic than most of the other groups. Especially Nights In White Satin . They were sympathetic to the crowd – that I remember quite well. And the beauty of the light at the time they performed was amazing.”

Still tripping, Hawkwind’s Dave Brock recalls making it into the main area in hope of catching The Moody Blues’ set: “After the fences came down, we actually went inside there to see some of the bands. I’d been given a Mandrax – a sleeping tablet to calm me down. I fell asleep, which was a bit of a shame, because I was quite looking forward to seeing them.”

Anticipation for Hendrix’s performance was high and building. But before Jimi it was the turn of Jethro Tull. Leader Ian Anderson ’s memories of the festival are not very fond ones, despite the band putting in a strong performance: “Things were going around both backstage and front of house that made it a little unpleasant for everybody. It was out of control, and the organisers were struggling to keep the thing from degenerating into something quite horrible. It was perhaps a testimony to the local police, and generally the welcoming residents of the Isle of Wight, that the thing happened at all.”

Interestingly, it was Tull’s refusal to play Woodstock that set up their Isle of Wight appearance.

“We were invited to play Woodstock and didn’t,” Anderson says. “Mainly because I didn’t want to spend my weekend among a bunch of unwashed hippies. It was too much of a defining moment for a brand new band. It would have been the beginning and the end for us – as it was for Ten Years After. As it turned out, I think it was a defining moment in that change from the hippy ideals to the rather dark and pragmatic side of music.

“At the Isle of Wight we knew we were unlikely to get paid, and we determined early on that this was something that we really just had to go through and try and keep a modicum of a smile on our faces. So we just kind of got on with it and did our bit. It was not a good gig, it was not a bad gig, it was just a little frenetic and a little tense.”

Not long after Tull had finished playing, the compere made an announcement that sent a palpable wave of excited anticipation through the crowd that had stayed on: “Let’s have a welcome for Billy Cox on bass, Mitch Mitchell on drums, and the man with the guitar, Jimi Hendrix.”

Finally, the performer who many had come to the festival to see, over and above anyone else, launched into what became an almost two-hour set. But – as evidenced by the 2002 DVD Blue Wild Angel: Jimi Hendrix Live At The Isle of Wight – what was expected to be a dazzling, thrilling performance fell very short of that.

Clearly, worryingly, something was wrong. Watched on the DVD, Hendrix appears dazed, distant; almost every song includes meandering guitar improvisation; vocal lines are fluffed. Additionally, Hendrix was constantly consulting with roadies instead of concentrating on his band’s and his own performance.

As The Who’s Pete Townshend reminisced in the 2001 DVD 30 Years Of Maximum R&B Live : “What made me work so hard was seeing the condition that Jimi Hendrix was in. He was in such tragically bad condition physically. And I remember thanking God as I walked on the stage that I was healthy.”

Lerner, however, disagreed: “I didn’t think he was in bad shape, I just thought he was tired,” he said. “He did great renditions of Red House and Machine Gun – which I think is as good as anything he’s ever done. Although admittedly he didn’t give the usual wild, waving around [performance].

“Before he went on, Jimi said: ‘How does God Save The Queen go?’ And then he played it. He said: ‘Everyone stand up for your country and your beliefs, and if you don’t, fuck you.’ Machine Gun is always great, but in this case [Hendrix said]: ‘Here’s a song for the skinheads in Birmingham. Oh yeah, and Vietnam. I almost forgot about that.’ Machine Gun goes on for about 17 minutes.”

Sadly, Jimi’s performance at Isle of Wight would be his last on British soil. Just over two weeks later he was dead, aged just 27.

Although many people continue to assume that Hendrix closed the festival, he was actually followed by performances from Joan Baez and Leonard Cohen , who played into the early hours of the following morning, before Richie Havens closed the whole thing at daybreak.

Lerner recalled the final performers. “[Cohen] said some very nice things about the radical movement of the time: ‘We’re a small nation, but we’re going to grow. We need our own land.’ I remember he had a lot of beautiful women singing with him – I was jealous. He had that kind of attraction, I think – the suffering poet [laughs].” “I don’t consider [Havens] the last, because he played at dawn. For me, the last was Cohen. I think [Havens] wasn’t on the stage – he was walking around singing off the stage. Singing at sunrise. It was extremely moving.”

With the end of Havens’s set, many of the remainder of the dwindling crowd made their way to the exits – bleary-eyed, hungry and unwashed. Although catastrophe seemed to hover over the festival throughout, it never came to a head. There would be many other British festivals in the wake of the turbulent 1970 Isle of Wight, and they continue today. But it was clear that such gatherings could not get by merely on the 60s peace and love ethos.

From now on, rock festivals were now big business, and, for many of those involved, money was now the star attraction.

Contributing writer at Classic Rock magazine since 2004. He has written for other outlets over the years, and has interviewed some of his favourite rock artists: Black Sabbath, Rush, Kiss, The Police, Devo, Sex Pistols, Ramones, Soundgarden, Meat Puppets, Blind Melon, Primus, King’s X… heck, even William Shatner! He is also the author of quite a few books, including Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music , A Devil on One Shoulder And An Angel on the Other: The Story of Shannon Hoon And Blind Melon , and MTV Ruled the World: The Early Years of Music Video , among others.

Bruce Dickinson is playing a “secret show” at a legendary venue this Friday: “Not so secret anymore.”

"Not everyone can say they played with David Bowie and Jimmy Page." Drummer Michael Whitehead on working with two giants of British music

Heavy music hit Tallinn Music Week like a blizzard: here's our guide to the seven best alternative bands we saw in Estonia

Most Popular

By Malcolm Dome 9 April 2024

By Matt Mills 9 April 2024

By Johnny Sharp 9 April 2024

By Neil Jeffries 9 April 2024

By Paul Elliott 9 April 2024

By Sid Smith 8 April 2024

By Henry Yates 8 April 2024

By Daryl Easlea 8 April 2024

By Stephen Hill 8 April 2024

By Vicky Greer 8 April 2024

By Rob Hughes 8 April 2024

Deep Friday Blues: Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac – “Oh Well” Live 1969

Sister Trio Call Me Spinster Zoom In On Warm Tones With Engaging ‘Potholes’ (ALBUM REVIEW)

Phish Announces New Album ‘Evolve’ out July 12th- Shares Title Track

Golden Age Thursday: Kool Keith “Dr. Octagon Showcase” Live 2008

Jazz Detective Zev Feldman Talks About A Vast Record Store Day, Part One: The Process (INTERVIEW)

New Orleans Musician Lynn Drury Finds Dockside Inspiration For Lively New LP ‘High Tide’ (ALBUM PREMIERE/INTERVIEW)

Hey You: Caitlin Cary Formerly of Whiskeytown Evolves Into Accomplished Multi-Media Artist (INTERVIEW)

John Fred Young Of Black Stone Cherry Serves Up Another Round of Candid Hard Rock Insights (INTERVIEW)

Album Reviews

Leyla McCalla’s ‘Sun Without The Heat’ Is Stripped Down Folk At Its Most Instinctive (ALBUM REVIEW)

Show Reviews

ZZ Top, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Black Stone Cherry Give Biloxi A Fitting Southern Rock Showdown (SHOW REVIEW)

Television & Film

Music World Gives Payback To An Overlooked Legend On ‘Lee Fields: Faithful Man’ (FILM REVIEW)

DVD Reviews

1982’s ‘Around The World’ Covers The Police On Their First World Tour (DVD REVIEW)

Other Reviews

Bill Janovitz Chronicles the Story of Leon Russell in ‘The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History’ (BOOK REVIEW)

Film Reviews

‘Licorice Pizza’ Can’t Carry Weight Of Its Parts (FILM REVIEW)

‘Loki’ Gives Us Loki vs. Loki in Episode 3 (TV REVIEW)

All the Movie Trailers from Super Bowl LIV

Commentary Tracks

2021 Holiday Movie Preview: ‘Ghostbusters: Afterlife,’ ‘The Power of The Dog,’ ‘House of Gucci’ & More

40 Years Ago Today – Rush Release ‘Grace Under Pressure’ Album

SONG PREMIERE: Goodnight, Texas Lay Down Fuzzy Rock Grooves on “The Money or The Time”

Sampha Turns Up Intimacy & Artistry Factor at Minneapolis’ 7th Avenue (PHOTOS)

CAUSTIC COMMENTARY: METZ, Maggie Rogers, Shabaka, BODEGA, Bad Bad Hats & More

Vinyl lives.

Portland’s Record Pub Serves Up Vinyl, Brews & Weekly Gatherings (VINYL LIVES)

These Walls

Amherst’s The Drake Is Making New Musical History In The Pioneer Valley (THESE WALLS)

Vintage Stash

The Replacements’ ‘Tim’ Let It Bleed Edition Proves Worth As Discerning & Durable Retrospective

TIME OUT TAKE FIVE: Falkner Evans, Franco Ambrosetti, Jan Hammer & More

One Track Mind

Emerging Artist J.S. Ondara Makes Voyage From Kenya to Minnesota & Astounds With ‘Tales of America’ (INTERVIEW)

Suds & Sounds

Suds & Sounds: Beale Street Brewing Co. Celebrates Memphis Music Through Craft Beer

Hidden Track

Movie Review: Louis C.K.’s ‘Tommorow Night’

ALBUM PREMIERE: Nicolette & The Nobodies Unleash Fiery Country Sound on ‘The Long Way’

SONG PREMIERE: Chris Smither Offers Earthy Folk Take on Tom Petty’s “Time To Move On”

SONG/VIDEO PREMIERE: Grace Pettis Struts Melodic Flair On Cathartic “I Take Care of Me Now”

- September 18, 2018

- B-Sides , Columns

I Was There When: Chicago Drives Home Transcendent Musical Experience at Tanglewood 7/21/70

- By Doug Collette

The stories behind Chicago’s vaunted appearance at Tanglewood is almost (but not quite) as fascinating as the performance itself. The original headliner for this date of the late Bill Graham’s Fillmore At Tanglewood in Lenox, Massachusetts was purportedly Joe Cocker, but neither he nor alternate choice Jimi Hendrix was unable to make the date. Now, it’s not a given the latter’s refusal of the booking led to Chicago’s, but it is known the guitar icon admired the guitar work of the late Terry Kath, so…

Adding further mystique to this piece of rock and roll history is its ready availability via the web: even though it’s never been formally sanctioned for release by Chicago itself, perhaps due to licensing issues with the estate of the aforementioned rock impresario. Such minutiae, however, turn trivial in the context of the group’s stellar performance this July night at the summer home of the Boston Symphony: even with the band on the cusp of widespread fame, based on singles culled from their sophomore album released earlier in the year, members of their burgeoning fanbase probably couldn’t expect anything so visceral or complex.

This venue’s flat sight-lines notwithstanding, as the ninety-minutes plus show progressed, the audience inside the open-air shed, as well as those further populating the lawn, no doubt found it increasingly riveting. Before too long, virtually all the attendees knew they were watching and listening to a band that was not only firing in all cylinders but also well aware of the elevated level of its musicianship. July 21, 1970, was one of those transcendent experiences music-loving concertgoers dream of.

Spurred on by Kath (who would die in 1978 in a tragic firearms accident), Chicago was equally tight and versatile as they traversed material from their debut album, Chicago Transit Authority , as well as Chicago II. A nd while “Make Me Smile” and “Colour My World” had not yet fully catapulted the band into the mainstream, the group’s dawning realization of their combined power and its effect on the attendees only added atmosphere to the event.

Chicago ran the gamut of composition and style during the course of this comfortably warm, crystal-clear night. Near-perpetual touring since the release of their debut album the previous spring had honed the ensemble’s musicianship, without leaving it rote or mechanical, so the dynamic shifts taking place in this single extended set ran the gamut: from near fifteen minutes of “It Better End Soon” to the comparatively short but sweet “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?,” hard-driving horns of “25 or 6 to 4” gave way to “Free Form Piano” and only then did the septet transition smoothly into the rousing suite titled “Ballet For A Girl In Buchanan.” including the aforementioned future hits.

The unified power in the playing had its corollary in the personal camaraderie among the band members. Taking the form of verbal acclamation of each other as well as regular rounds of delighted smiles, Chicago may have been surprising itself with the splendor of its playing here in the Berkshires, but that only heightened its infectious impact on the attendees and to a great degree helped elicit (and no doubt increase the volume of) the thunderous ovation(s) and call(s) for encore(s). Judging by the wan sound of promoter Graham’s farewell to the audience (readily available to hear on the various aforementioned internet versions, there’s little doubt everyone present was fully satiated and thoroughly drained by the time this evening concluded.

Setlist: Chicago – Tanglewood Lenox, MA – July 21, 1970

Intro In The Country Free Form Piano Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is? 25 or 6 to 4 Poem for the People I Don’t Want Your Money Mother It Better End Soon Beginnings Ballet For A Girl In Buchannon (Make Me Smile) / So Much To Say, So Much To Give 06:40 Colour My World / Make Me Smile I’m a Man Terry Kath Outro;

Bill Graham Closing Announcements.

Related Content

4 responses.

I was there at my first live concert at 15 years old. Awesome to see it again. A real flashback. I think the ticket was printed “Joe Chicago” Didn’t know what to expect.

I consider this the best video taped Chicago concert in the “Terry Kath” era. I’ve seen them with and without Kath and I hate to say it but they just don’t seem to match the musical intensity. Yes, I realize they are older and only three original members remain, but their music is such that even as I’ve played most of their tunes a trumpeter in various bands, the intensity and excitement of playing those horn trio parts in a rock setting is just incredibly exciting ESPECIALLY if you have a lead guitar of Kath’s caliber—a leader who really HAD to control things on stage,. Though Keith Howland is a tremendously talented guitarist with great musicianship in all areas—–ensemble and solo as well as rhythm- he’s a different style guitarist . Maybe if Lamm would write some soloistic stuff for him , the excitement could return in a different yet equal way. Will always love them. anyway. THey are the best musicians in the rock world.

I was there! A fan – and 16 years old counselor at a local camp in Connecticut – this concert immortalised them. The music was powerful and the musicianship was crazy. I’d seen most of the greats: Joplin, The Doors, The Won. The Stones – yet this July date remains the single best concert I’d ever seen. Good to see it’s not been forgotten.

My late sister and her husband lived in the last house you saw on road up South Mt. headed to the venue’ Had tix and was fired up for the Cocker road show,then heard it would be Hendrix…OK,we’ll take that in a heartbeat. Then Chicago…you mean CTA,those guys who cover Spencer Davis so well. I guess that will be OK;I’m staying about 7 minutes from Tanglewood. 3 of us,2 joints n 1 cold bottle of Boones Farm and Holy Shit who the fk do we have here. I’ve got a solid 50 years plus of live rock shows and nobody has knocked this show out of my All Time top 10 shows. Just the incredible surprise of how hard this band cooked for 90 mins.I’m not a prisoner of Rock n Roll,Bruce,I’m a volunteer.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Posts

New to glide.

At The Drive-In’s ‘In/CASINO/OUT’ Gets Record Store Day Vinyl Reissue (ALBUM REVIEW)

Aaron Lee Tasjan Progresses With Glam Pop-Leaning ‘Stellar Evolution’ (ALBUM REVIEW)

Keep up-to-date with Glide

Email Address*

Joe Cocker’s ‘Mad Dogs & Englishmen’: Inside the Triumph and Trauma of a Legendary Tour

By David Browne

David Browne

When singer Rita Coolidge attended the premiere of Mad Dogs & Englishmen , the 1971 doc that chronicled the Joe Cocker –fronted tour of the same name, the experience was far from celebratory. “I started shaking and crying and it all came back to me,” she says. “I got up and left and got in my little VW and drove home. My friends were so worried about me that they followed me. I don’t know if I’m over it yet.”

Although it’s become something of a footnote in pop history, the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour was historic: It captured British soul singer Cocker at the peak of his career, and its joyful blend of gospel, soul, blues, and every other type of Americana powered the double album that documented the 1970 run into the Top 10 (with Cocker’s remake of the Box Tops’ “The Letter” also a hit). It also made a star out of bandleader Leon Russell, who exuded bad-boy cool on screen. But the run of shows was also fraught: An already frazzled Cocker was frustrated that Russell was in command, drugging and partying were daily occurrences, and out of the blue, drummer Jim Gordon, then Coolidge’s boyfriend, punched her so hard that she slammed against a wall.

The saga of that tour — and a tribute concert that reunited many of its participants — is newly told in Learning to Live Together: The Return of Mad Dogs & Englishmen, a doc that will premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival later this month before arriving for a limited theatrical run in October via Abramorama. Directed by Jesse Lauter, the film time-shifts between the 1970 tour (with clips from the first Mad Dogs movie), footage from the commemorative gig at the Lockn’ Festival in 2015, and interviews with the surviving players of the original shows. Also offering insights are Steve Earle and manager Jon Landau, who each caught a Mad Dogs show back in the day, and longtime Rolling Stone writer David Fricke.

But given the often dramatic and sometimes disturbing back story of the tour, what started as a straightforward film about that moment in time and the 2015 reunion became more than that. “While they were filming, they realized there was more meat on the bone than we thought,” says Derek Trucks, whose Tedeschi Trucks Band, co-fronted by his wife Susan Tedeschi, served as the backing band at the tribute gig. Of the sometimes unsettling moments that the movie explores, Trucks says, “It’s a tough place to go, but if you avoid that stuff, it starts to feel disingenuous at times.”

Editor’s picks

The 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, the 50 worst decisions in movie history, every awful thing trump has promised to do in a second term.

The Mad Dogs tour was chaotic both on paper and in practice. Cocker, already coping with an overwhelming wave of post-Woodstock fame, was told by immigration authorities that he had to tour right away or lose his working papers. Coolidge says the actual reason was the dark underbelly of the sometimes mobbed-up music business. “It wasn’t so much about not working in the States but, ‘If you don’t do this tour, you’ll get your legs broken,’ ” she says. “That was common knowledge in the group — that threats had been made that if Joe didn’t do the tour, he would be hurt.”

With only a week to prepare, Russell was hired to pull together a 10-piece band — and a 10-person group of backup singers called the Space Choir — and rehearse for the 48-show run. Cocker, Russell told RS in 2015 , “was pretty wrecked when we started out. I said, ‘Does it sound good to you?’ and he said, ‘It never sounds right to me.’ I didn’t know how to take that. So I said, ‘Shit, I’ll just do whatever I want.’ ” The tour manager, Sherman “Smitty” Jones, was a former pimp, and Cocker was seen tossing down any and every pill given to him on the way to the stage. “It was party-party-party,” says Coolidge, who says she abstained from most of that. “They were having orgies every night. I would hear about them the next day.”

By the end of the shows, Cocker was fried and broke. “Joe was just worn out and so beat up and penniless,” Coolidge says. “The heart went out of him for a while. He just disappeared inside himself.”

The Tedeschi Trucks Band, which had modeled itself after the size and horn-rooted arrangements of that ensemble, had long wanted Cocker to join them onstage and perform cuts from throughout Cocker’s career. All involved had finally settled on doing such a show at Lockn’ in 2014 — part of the festival’s tradition of presenting a special, one-time get-together each year. Cocker bowed out at the last minute, but a few months later everyone knew why; he had been battling lung cancer and died that December. Tedeschi and Trucks decided to proceed with the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tribute plan anyway, to honor both the album and Cocker.

When the notoriously reclusive Russell agreed to come aboard, having previously joined the Tedeschi Trucks Band onstage, others expressed interest. “I was concerned that there wouldn’t be enough of us left alive to make it worth the while,” Coolidge laughs. She also adds, more seriously, “I also knew Leon was having some pretty serious health problems. I was concerned about him being put in a position that would tax his frailties.”

But by showtime, the lineup included former Mad Dogs like Coolidge; singers Claudia Lennear, Pamela Polland, and brothers Daniel and Matthew Moore; keyboardist Chris Stainton; and percussionists Chuck Blackwell and Bobby Torres. (Gordon, currently in prison for killing his mother, was not invited, and the tour’s other drummer, Jim Keltner, respectfully bowed out in light of his disinterest in traveling.) As Tedeschi Trucks booking agent and movie co-producer Wayne Forte says, the criteria for inviting players was “healthy, alive, and not in jail.”

Related Stories

He told george harrison his tour sucked – and five other things we learned from ben fong-torres, flashback: brian may, eric clapton play 'with a little help from my friends' with joe cocker.

The nearly four-hour Lockn’ show went off with few hitches; Warren Haynes, the Black Crowes’ Chris Robinson, and Widespread Panic’s John Bell filled in for Cocker at various points (Dave Mason also sang lead on his “Feelin’ Alright”). At the last minute, Russell agreed to reprise “The Ballad of Mad Dogs & Englishmen,” the solo Russell studio recording heard in the original doc. Despite his health issues, which led to his death in 2016 after a heart attack, Russell held up for the entire show and, despite his surface crustiness, marveled at the stability of the Tedeschi Trucks lineup compared to the original Mad Dogs crew. “Leon was shocked by how long we’ve been together,” says Tedeschi. “He said, ‘How do you keep nine or 12 people together this long?’ They did it for a year and they had to all take time off.”

During interviews for the documentary, some of the tour’s tangled personal relationships emerged. “There were so many different undercurrents of emotions we weren’t aware of,” says Trucks, “but we could feel it.” Numerous hookups are hinted at. Coolidge, who was in a relationship with Russell before the tour, says the two had overcome their past difficulties. “In the years right after the tour, I’d see him and he would pretend I wasn’t there — he would look right past me,” she says. “He finally relaxed, one or two of his marriages later. Things got resolved over the years.”

When Cocker crashed hard after the tour, some of the criticisms were leveled at Russell, who more or less ran the shows. In Learning to Live Together , Russell, who could be guarded, addresses the backlash he experienced, saying he wished Cocker had come to his defense. “I could definitely sense resentments for it, like he almost couldn’t win in that situation,” says Lauter. “Doing this show was almost like his way of healing his relationship with Joe. That’s why I titled the movie Learning to Live Together . Everyone had musical and romantic and business relationships, and you pick up on how everyone was trying to figure it all out back then.”

Adds Lauter, “When it comes down to it, the film is ultimately a story about the great generational bridge and healer that is music. We knew it the moment the band started playing ‘The Letter,’ the first song at the first rehearsal, and you could hear Claudia’s backing vocal cut through the Space Choir. All the resentments, past drama and trauma were out the window.”

The movie’s dramatic highpoint arrives when Coolidge recalls the moment Gordon punched her in a hotel, after he’d invited her to step outside a room where a party was going on. “I know people are tired of talking about the #MeToo movement,” Coolidge says, “but it was very real, even back then, and it’s important to talk about that stuff. As a child I was never hit by an adult, or by anybody. Jim was four times my size and I was 100 pounds; he could have pinched me and it would have been enough. I had a huge shiner and I had to go onstage with it. Everybody knew it. I needed them to be part of my protection since I couldn’t do it myself.”

Forte says there was talk of how much of the backstage drama, including Coolidge’s unsettling story, to include. “There was a lot of conversation going back and forth: Is all that going to be a potential downer?” he says. “You don’t want to have people walk out of the movie depressed. But I, for one, felt it’s part of the story. It needed to be in there.” Adds Tedeschi, “It’s real life. Things happen and people like to know about someone who has gone through those things and made it through the dark side. It’s not all bad and dark.”

Transforming footage old and new into a feature film proved to be a daunting task, which accounts for the six-year delay between concert and movie. Unable to find a big-money investor, the producers raised more than $700,000 from various parties, then spent two years clearing the rights to songs by Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and others whose tunes were performed on the Mad Dogs & Englishmen album. Lauter had hoped to include some of the rumored hundreds of hours of outtakes from the original doc (which Russell, in the movie, wryly calls “300 hours’ worth of really X-rated stuff”), but those were never unearthed. (Whether those reels were misplaced or perished in the 2005 fire at Universal Music’s storage facility remains unclear.) Learning to Live Together only includes portions of the Lockn’ show, but Trucks says a live album of the complete show will be released at some point.

Coolidge, at press time, had not yet seen the film. But it seems unlikely that her traumatic experience at that premiere, 50 years ago, will repeat itself. “We’re a lot older, so there were no triggers,” the now–76-year-old singer says. “I didn’t feel like I was really back there. Hopefully you gain some wisdom and grace with age. Looking at it from this part of my life, I really valued the experience. I remembered the good parts and have no regrets.”

Shakira joins Bizarrap at Coachella, announces world tour

- Coachella 2024

- By Tomás Mier and Suzy Exposito

Kelly Clarkson Covers Chaka Khan's 1983 Hit 'Ain't Nobody'

- Through the Stars

- By Charisma Madarang

Dua Lipa, Future, Metro Boomin', Girl in Red, and All the Songs You Need to Know This Week

- By Rolling Stone

Solar Eclipse Skyrockets 'Total Eclipse of the Heart' Streams by 480%

- Solar Flare

- By Ethan Millman

'I Can't Blame Myself:' Tini Finds Peace After Grappling With Mental Health and Child Stardom

- By Tomás Mier

Most Popular

Jodie foster pulled robert downey jr. aside on their 1995 film set and told him: 'i’m scared of what happens to you next' because of addiction, where to stream 'quiet on set: the dark side of kids tv' online, sources claim john travolta is ‘totally smitten’ with this co-star, angel reese signs multiyear agreement with panini america, you might also like, how o.j. simpson, a busted pilot and his huge network supporter loomed over nbc just as it found ‘must-see tv’ success, lauren sanchez’s style evolution through the years: jeff bezos’ fiancée’s fashion history, the best running water bottles according to marathoners, eleanor coppola, ‘hearts of darkness’ documentarian and francis ford coppola’s longtime wife, dead at 87, arizona coyotes are no more, will move to salt lake city.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Verify it's you

Please log in.

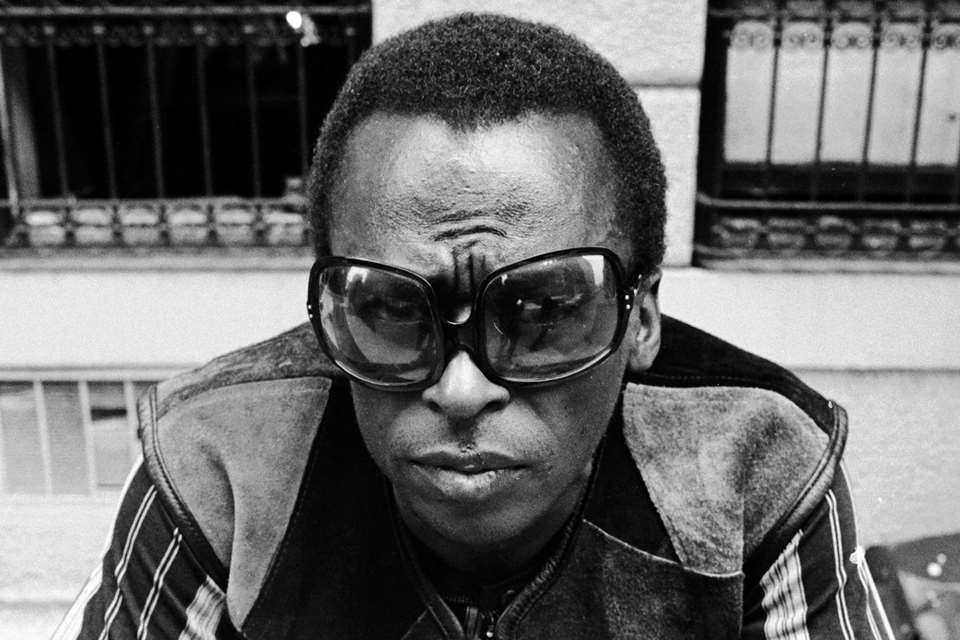

Miles Davis at the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival: What really happened

Jon Newey Tuesday, October 12, 2021

Miles Davis played the biggest gig of his career when he brought his groundbreaking new Bitches Brew band to the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival, still the largest ever music event to take place in the UK. Jon Newey was there to witness this historic weekend

By midday on Saturday 29 August, the writhing sea of flesh flowing into the already over-crowded and primitive infrastructure of the vast makeshift arena was on an unprecedented scale, and more were arriving every minute. From the stage the size of the audience must have seemed beyond imagination. The numbers for the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival estimated by the Guinness Book of World Records were between 600,000 – 700,000, which still remains the biggest audience for a music festival in the UK. Often referred to as Britain’s Woodstock, and somewhat overshadowed in the media by that 1969 landmark American event, they both shared the dubious distinction of being declared a free festival after the attendance grew unmanageable and was overrun by tens of thousands of ticketless hippies. In the IOW’s case, a contingent of French anarchists and revolutionaries, protest-hardened from Paris 1968, also showed up and toppled fences, insisting all music should be free. Interestingly there was nary a Bobby in sight.

For Miles Davis , used to playing smoky jazz clubs with audiences up to 300 or so plus the odd summer jazz festival such as Newport, where the audience numbered around 5,000, the sheer mass of humanity stretching as far as the eye could see that weekend of Friday 28 - Sunday 30 August must have shaken even his suave demeanor. In the event, it would turn out to be the biggest audience that he, or any other jazz musician, would ever play for.

Miles Davis at the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival (photo: Charles Everest)

Davis, then 44, and one of the final names to be added to the bill, knew the scene was changing – and how. Jazz clubs had been closing down and reopening as rock clubs and discotheques, and the young collegiate audience that jazz had attracted from the late 1940s, through the 1950s and into the 1960s was fast moving to the new underground rock music, influenced by blues, jazz, folk and psychedelia.

Davis knew he had to remodel or be sidelined by fast changing events and his new electric band, who’d recently played the hippie shrines, San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium and New York’s Fillmore East, could stand tall both musically and visually among the forward-looking, cross-genre IOW festival line-up, which ranged from rock giants Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Doors, Free, Jethro Tull and Emerson, Lake & Palmer to the powerhouse funk and soul of Sly & the Family Stone and Voices Of East Harlem; key singer-songwriters, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez, folk-jazz artists such as Pentangle, Richie Havens, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, and jazz influenced, horn-laden rock bands Chicago and Lighthouse.

Some of the critics were talking about how aloof I was, but that didn’t bother me; I had been this same way all of my life

The underground paper Friends (later known as Frendz ) referred to Miles’ addition as ‘the strangest choice of the festival… definitely the most musically satisfying,’ while Record Mirror ventured: “Miles Davis is going to be the one to watch. Miles is going to give the Isle of Wight that extra dimension”. And they weren’t wrong.

The festival line-up echoed the wide-open eclectic taste of the period as many rock fans were ravenous for new music while discovering jazz for the first time – hardly a giant step considering most rock bands of any worth then improvised at length and spoke freely of their jazz influences. There was talk too of Miles and Hendrix getting together afterwards to record in London, possibly with Gil Evans.

However, Miles went back to New York and Hendrix to three European festival dates before returning to London and tragically dying on 18 September of inhalation of vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. A potential meeting of the spirits, so near but yet so far.

We were flown in by helicopter because of traffic. Seeing all those people was a really awesome feeling, this is what Miles had wanted to get to and there it was. We were all pretty blown away. Jazz bands had never played for that big an audience before. It was also one of the best performances that we played as a band

When I first pitched up on Friday lunchtime at the East Afton Farm site, situated on the island’s western flank, the mellow sunrise had soon cast aside any early mist to reveal a gloriously hot day, which thankfully dictated the weather for the entire weekend. The audience had already expanded out of the festival site up the side and length of Afton Down, now dubbed Devastation Hill, much to the organiser’s annoyance. It was a vast, undulating encampment of tribes, tents and Tibetan scarves, wreathed in marijuana, cigarette and incense smoke and gathered before the largest outdoor stage and WEM PA speaker towers constructed up to that point. A veritable temple of sound for a generation in motion.

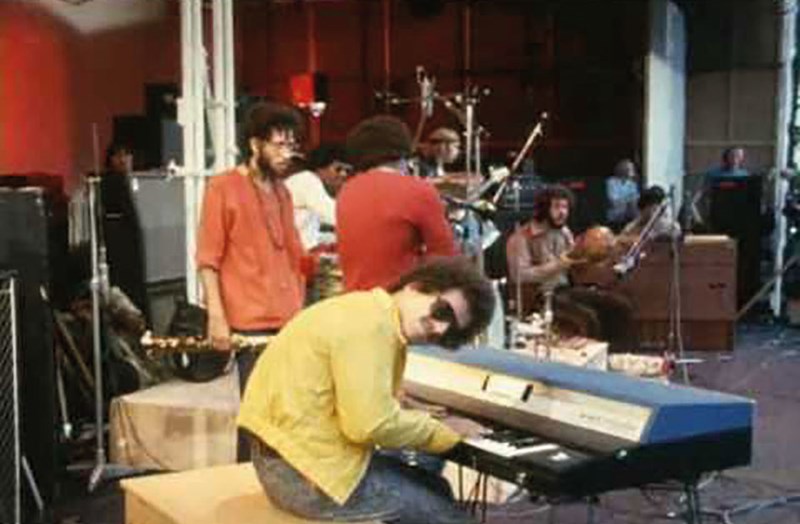

When Miles arrived on the island he was accompanied by his girlfriend Jackie Battle, (not Betty Davis who gets tagged in photos, according to Miles’ autobiography) and his band, now including new saxophonist Gary Bartz alongside Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Jack DeJohnette and Airto Moreira.

In the 12 months since recording Bitches Brew and turning the jazz world on its head, his foot had barely been off the pedal. Not content with forging a whole new direction with this iconic recording, he’d also cut the tracks that later became Big Fun , as well as recording Jack Johnson , tracking three live albums, Live-Evil , Black Beauty and At Fillmore , (all released in 1971), and playing numerous concerts in the USA and Europe.

Keith Jarrett in a trance (photo: Eagle Rock Entertainment)

At the IOW festival, the presence of producers Teo Macero and engineer Stan Tonkel, along with the Pye Mobile Recording Studio suggested the tapes would be rolling here too. Just as well, as this extraordinary, short-lived line-up only lasted three concerts. A week before, on 18 August, they played the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood, Massachusetts on a bill sandwiched between Santana and Voices of East Harlem, and the Isle of Wight turned out to be their final performance. Barely two weeks later Corea and Holland quit to form Circle with Anthony Braxton and Barry Altshul

By the Saturday afternoon the playful peace ‘n’ love atmosphere began to get a little frayed around the edges, with drug squad officers dressed in hippy clothes infiltrating the crowd, and confrontations between gatecrashers and hired security guards with Alsatian dogs. Joni Mitchell’s solo acoustic set was first disrupted by a noisy helicopter which had the audience booing and shouting at it, before being further unsettled by an American hippie known as Yogi Joe, who Mitchell had previously known from a yoga session. He’d crawled onto the stage and sat by her piano before attempting to grab the microphone to speak to the crowd. Rapidly he was grabbed and dragged off stage where he continued to berate the organisers about how it should be a free festival. His incursion had Mitchell briefly in tears, though she finished her set to a standing ovation.

Meanwhile, Miles had showed up prior to Mitchell taking the stage and was introduced to her by festival MC Rikki Farr before he wandered backstage to hang-out by the mobile recording unit, talking with Macero. His moody, aloof glare suggested he didn’t exactly share the festival’s community spirit, a point that was picked up by Melody Maker in its post-festival coverage. Somewhere it hit a nerve and stayed. Two decades later Miles referred to it in his autobiography: “Some of the critics were talking about how aloof I was, but that didn’t bother me; I had been this same way all of my life.”

Miles pointed his midnight blue lacquered, gold-etched horn at the sun’s descending rays, narrowed his eyes and let rip with a feral, morse code-like blast

The festival’s DJ Jeff Dexter, a key figure on London’s underground music scene since 1967, was backstage where the atmosphere veered between late running chaos and hippie cool as Tiny Tim’s psychedelic vaudeville entourage arrived for their afternoon set.

“I attempted to engage Miles in conversation but he was somewhat negative about the rock bands, festival vibe and Tiny Tim’s wacky antics,” says Dexter. “He didn’t really talk much, though Rikki Farr, who was a big Miles fan, was embarrassingly all over him. Miles’s attitude was certainly in contrast to most of the other musicians.”

But now though it was the trumpeter’s turn. As dusk approached, the band cranked up a jagged funk vamp before Miles took to the stage, street-cool in red leather jacket, studded jeans and silver stack-heel shoes. While some artists were, not unnaturally, overawed by the vast size of the audience, Miles and the band appeared unfazed and slammed into their set with such ferocity that it jerked the audience around me from its stoned afternoon ennui into a bustle of excited head-turners. Miles pointed his midnight blue lacquered, gold-etched horn at the sun’s descending rays, narrowed his eyes and let rip with a feral, morse code-like blast. This was jazz Jim, but not as we knew it.

Underpinned by the relentless drive of Dave Holland’s circular James Brown-like electric bass figure, Jack DeJohnette’s hustling boogaloo and Airto’s nagging cuica, Miles squirted hard clusters of notes and jabbing trills, freezing the front rows with his terse boxer’s stare before Gary Bartz stepped forward to double with him on ‘Directions’ angular theme, uncoiling into a snaking, eastern tinged soprano improvisation. The tension built, the band empathy locking into a thick, churning groove stretched every which way by the warp-factor keyboards. Miles dipped his head and on cue the band turned down the heat as he breathed a languid five note motif over a deep reverberating bass drone and rattling shekere, signaling the route to ‘Bitches Brew’. Amidst the dust, heat and chaos of this enormous event, and surrounded by the loudest, most electric line-up he’d yet played with, Miles was still and centered, listening hard to the music’s in-the-moment creativity, navigating direction with ‘coded-phrases’ as this continuous modal free-funk improvisation pushed the “sound of surprise” into another dimension.

We helicoptered in. It was totally chaotic. A surreal experience standing on stage in front of the mass of people. Hard to tell what they got from the stage or what they didn’t get. It seemed to be like a massive beach party. Backstage was even more chaotic than out front. That was a fun band though! It was nice to see so many people enjoying hanging out together. For me it was a blip in time. The real thrill was playing with Miles and that band. Keith and I were on opposite sides of the stage. His instrument and my instrument sounded awful. The trumpet, saxophone, drums, percussion and bass won the day.

He opened out on long sustained trumpet notes and pinched squeals while Holland and DeJohnette nudged the ebb and flow, ratcheted the pressure and built a deeper, smoking funk force, almost Meters-like in its greasy swagger. Jack’s wide grin and Holland’s boyish smile told all, it was as though the music was playing them. Bartz re-entered the fray with a slow burn alto solo while Corea, poised and purposeful, wound slippery lines around the more experimental Jarrett, whose head and body vibrated to every note, twisting and turning, dipping and diving, lost in a personal dance with the music.

In the space of the 11 days since Davis played Tanglewood (recorded by Columbia and finally released as part of Bitches Brew 40th Anniversary box set), the band now sounded harder, funkier and in places freer. Corea and Jarrett may have been using inferior hired keyboards at the IOW – Corea a Hohner Electra piano and Jarrett an RMI electric piano/organ – but both were treated with primitive but strikingly atmospheric effects, including distortion, wah-wah and phase shifter, twisting and contouring the sound into wild new shapes. They were placed on opposite sides of the stage and their probing lines and spacey textures would spin off and collide with each other (monitoring was primitive back then), ramping up the intensity and contrapuntal tension of the music.

Like Tanglewood’s similar set, this 38-minute long uninterrupted piece also took in ‘It’s About That Time’, a short quote from ‘Sanctuary’, ‘Spanish Key’ and then closed out with ‘The Theme’. When asked afterwards what this piece was called, Miles, said: “Call it anything” which became the title of Macero’s 17-minute edit of the performance on the CBS triple LP, The First Great Rock Festivals of the Seventies – Isle of Wight/Atlanta Pop Festival , released in August 1971.

Thankfully the entire weekend was caught on film by director Murray Lerner and a crack team of cameramen. Unlike Woodstock though, the footage didn’t turn into a blockbuster movie. Due to all manner of artistic differences and financial arguments between the organisers, Lerner and lawyers, it took over 25 years to surface as Message to Love , first shown on BBC TV in 1995. It featured a shortish edit of Miles’ set alongside most of the big names, and included backstage and audience footage and commentary, Rikki Farr’s on-stage rants at the fence topplers and a retired IOW naval commander complaining of communist plots and “hippies fucking in the bushes”.

Five years later individual DVD releases started to appear from Eagle Rock containing complete artists’ performances, and in 2004 the full 38-minute Davis set was issued as Miles Electric – A Different Kind Of Blue , which also included recently filmed interviews with all the remaining band members (this DVD was reviewed in Jazzwise Feb 2005). It remains one of the most intense and mesmerising filmed performances from his entire career as he brought his new music to a younger, more diverse audience surfing the wave of the counter-cultural zeitgeist, many of whom, including this writer, would subsequently rush out to buy Bitches Brew and help it become one of the biggest-selling jazz albums of all time.

Murray Lerner’s film not only captures up close the fiery, seat-of-the pants intensity of the performance, but also some of Miles’ most fleetingly intimate and melancholic moments, caught in profile and silhouetted against the falling dusk as his final note is carried off into the cool evening air. He pauses to look at the crowd before slinging his jacket and bag over his shoulder and departing the stage while the band builds to a climatic, drone-like finish. In the deepening shadows behind the amplifier backline he stops for a moment as the crowd erupts into a standing ovation, screaming for an encore. A half-smile plays across his lips as he looks, momentarily, like he might return to the stage to give them more. But he’s Miles Davis, he doesn’t have to.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of Jazzwise. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!

Related Articles

Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew at 50: “Aphex Twin, Brian Eno, Portishead, Flying Lotus and Joni Mitchell have all cited the album as an influence, while Radiohead’s OK Computer was directly inspired by it”

How Miles Davis put together ‘the greatest rock ’n’ roll band you ever heard’

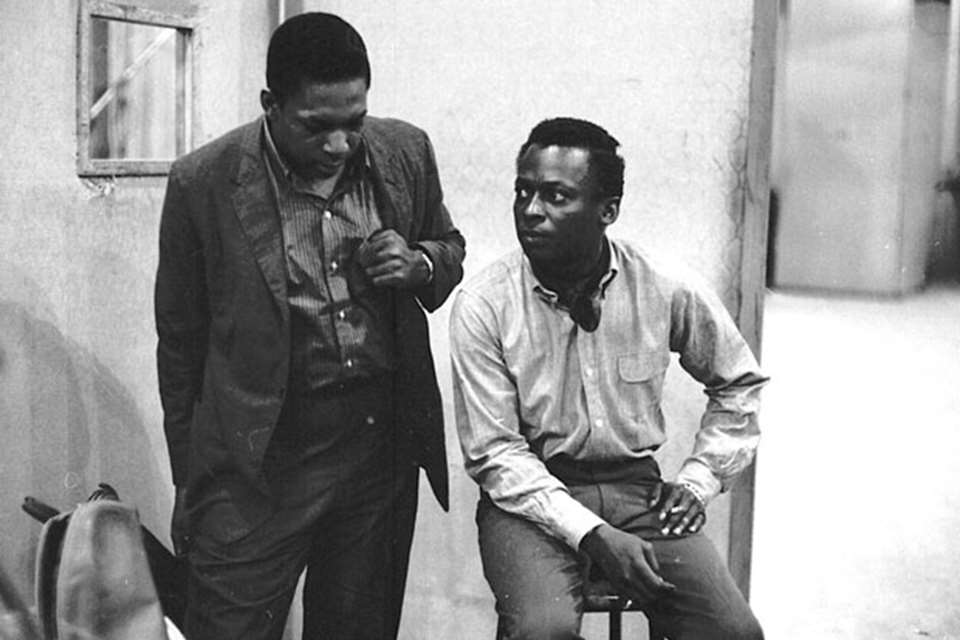

Miles Davis and John Coltrane: Yin and Yang

Miles Davis – The Lost Quintet

Kind of Blue: how Miles Davis made the greatest jazz album in history

Subscribe from only £6.75.

Start your journey and discover the very best music from around the world.

View the Current Issue

Take a peek inside the latest issue of Jazzwise magazine.

The Who Tour 1970

The Who Tour 1970 was a series of performances and tours by The Who in support of both their Tommy and Live at Leeds albums.

- 2 Live releases

- 3 Tour band

- 4.1 European Opera House and live recording dates

- 4.2 US tour

- 4.3 August–September dates

- 4.4 UK tour

- 5 Tour dates

- 7 References

- 8 External links

As in most of 1969 , the band's stage act was dominated by the stage performance of the rock opera Tommy , which had been the centerpiece of their show since the previous spring. The year began with the group bringing Tommy to various European opera houses , a trend they had begun in December 1969 when they performed at the London Coliseum . Included were January stops at the Champs-Elysees Theatre in Paris, the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, and three opera houses in Germany. The band then focused again on recording a live album, having abandoned the idea of wading through the hours of tape they had from recording shows during their North American tour the previous autumn. While 14 February Leeds University and 15 February Hull City Hall performances were both recorded, only the Leeds recording was deemed suitable for release, as the bass track was inadvertently not captured during the first few songs at the Hull show. The result was the legendary Live at Leeds , which became a hallmark live rock album and has been released three more times since its initial May 1970 debut (the 2010 "Super Deluxe" edition would include both the Leeds and Hull performances for the first time).

After beginning recording sessions for a planned new album, the group returned to the United States for a 30-day tour in June to support Live at Leeds . In the year since the release of Tommy , the group had become rock superstars and now commanded considerably larger venues than on previous stints in the country, when they played mostly in theatres and colleges. The tour began with the band's final opera house date, as they performed two shows at New York City's Metropolitan Opera House in what was erroneously billed as their final performance of Tommy (which in reality was kept in their act for the rest of 1970). While the rock opera remained the focal point of the set, the band also featured their latest single, " The Seeker " on this tour, although it was dropped after only two weeks and would not be performed again until 2000 . They also added some material from their in-progress album (eventually abandoned in favour of Townshend's Lifehouse project), performing " Water " and "I Don't Even Know Myself" regularly; " Naked Eye ", although unfinished in the studio, was performed in various arrangements on the tour as well, generally during the long show-ending jams catalysed by " My Generation ". The group's stage show on this tour would basically remain for the rest of the year.