- Prehistoric

- From History

- Cultural Icons

- Women In history

- Freedom fighters

- Quirky History

- Geology and Natural History

- Religious Places

- Heritage Sites

- Archaeological Sites

- Handcrafted For You

- Food History

- Arts of India

- Weaves of India

- Folklore and Mythology

- State of our Monuments

- Conservation

Tracing Fa-Hien’s Journey Through India (399 CE - 414 CE)

- AUTHOR Aditi Shah

- PUBLISHED 08 February 2021

“In this desert, there are a great many evil spirits and also hot winds; those who encounter them perish to a man. There are neither birds above nor beasts below. Gazing on all sides as far as the eye can reach in order to mark the track, no guidance is to be obtained save from the rotting bones of dead men, which point the way.”

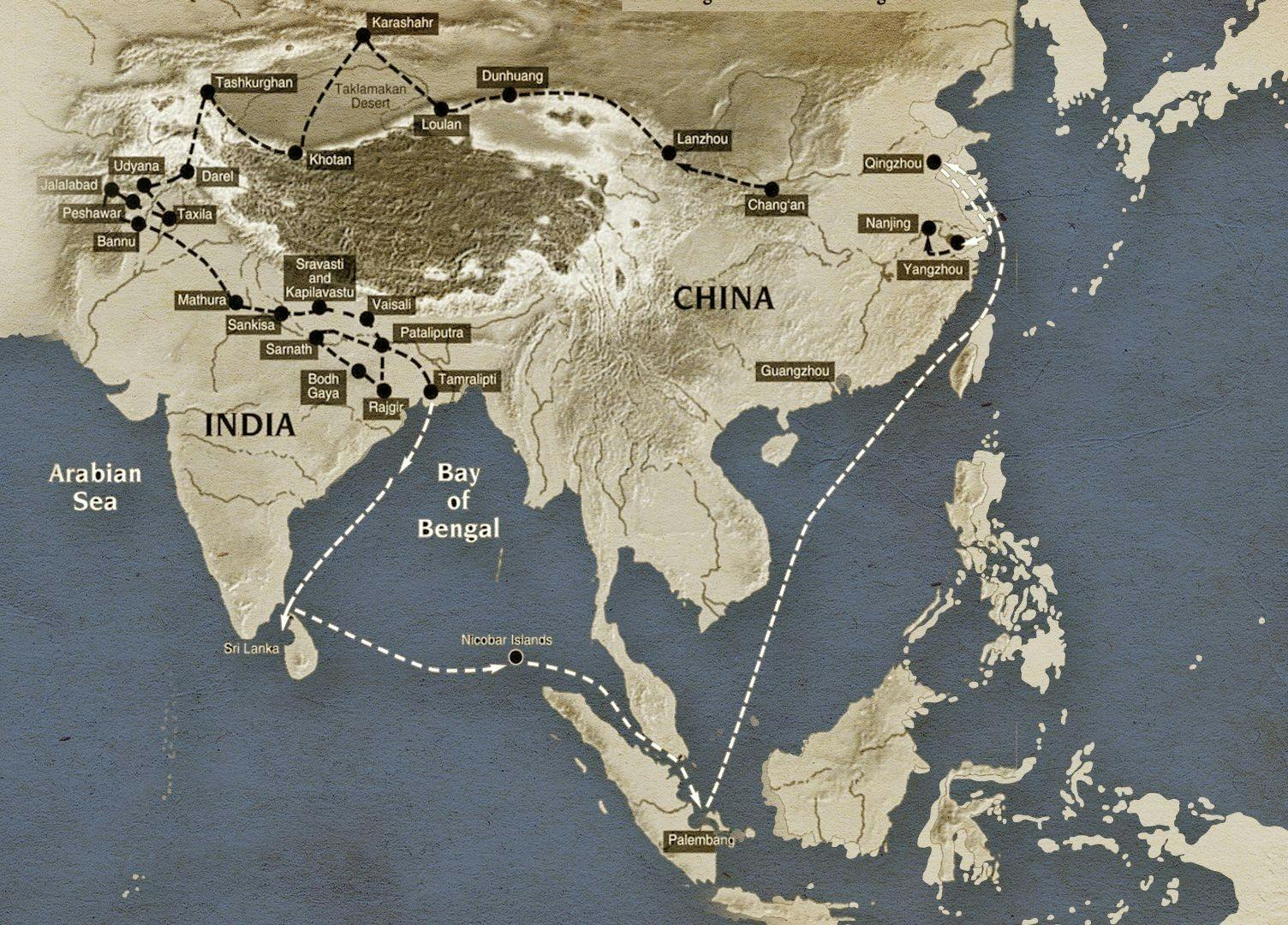

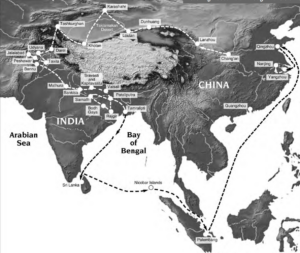

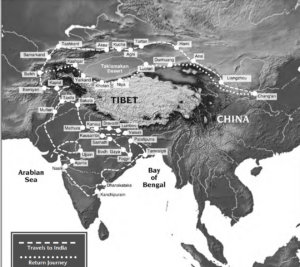

That’s an excerpt from the travel writings of Fa-Hien, a Chinese monk who left Chang’an in 399 CE, at the age of 62, and set forth on an expedition through Central Asia to India, and ultimately Sri Lanka. Accompanied by four others, he was on a mission to visit the land of the Buddha and search for Buddhist texts.

The journey was not easy. Sixteen hundred years ago, the Gobi Desert was untracked and the mountain passes of the Himalayas perilous to pass. It took months to get from one place to another. Weather conditions ranged from scorching heat to sub-zero cold and, with most of the journey done on foot, exposure was a very real threat. In addition, there were wild animals and bandits lying in wait.

So Fa-Hien’s quest was, quite literally, a legendary one. Centuries later, the travels of this monk, who spent 15 years on the road, would reveal to the world intricate details of life on the subcontinent. For instance, if we know what Patna looked like at the time and what festivals were celebrated in Sri Lanka, we have largely him to thank. As he travelled across what is now Pakistan, Nepal, Northern India and eventually to Sri Lanka, he recorded his observations in a travelogue titled Fo-Kwo-Ki (Travels of Fa-Hien).

Fa-Hien was one of the earliest Chinese traveller-pilgrim to make his way to India. Not since Indica by Megasthenes (4th-3rd century BCE) and ThePeriplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE) had there been a major contemporary account of the subcontinent, by visitors who viewed it – until Fa-Hien’s writings in the 5th century CE.

Between the 3rd century BCE and 2nd century CE, the Buddha’s teachings had spread far and wide. While the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (r. 269 - 232 BCE) sent his missionaries to places like Greece, Mysore and Myanmar to preach Dhamma, the land trade routes of Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha and the Indian Ocean trade network too became a conduit.

Under the Kushana Emperor Kanishka (r. 128 – 150 CE), who adopted Buddhism, the religion made its way deep into Central Asia and China. The Kushanas controlled an area that stretched from present-day Kabul through northern Pakistan and north-west India, and from the frontiers of China to Mathura and beyond in the Indo-Gangetic plains. These were also strategically important lands situated along the Silk Road. Along with merchants and goods, monks and Buddhism too began to make their way out into the world.

Travelling monks left markers along their trails — along the passes of Gilgit-Baltistan, there are still hundreds of images of Buddha and Boddhisattavs carved into stone.

Fa-Hien was among the first monks to take a reverse route, back along the Silk Road, to the Indian subcontinent. He began his journey in North-Central China, visiting as many Buddhist shrines as he could. And we know this because he documented everything. His travelogue, compiled after he returned home at the age of 77, is filled with invaluable accounts of what life was like, the places he saw and the nature of Buddhism at the turn of the 5th century.

Who Was He?

Fa-Hien was orphaned at an early age and spent most of his adult life in Buddhist monasteries. During a visit to Chang’an, an ancient capital city, the devout Buddhist was taken aback by the torn and weathered state of the Books of Discipline (known to us as the Vinaya Pitakas , which contain the monastic code for Buddhist monks and nuns).

Fa-Hien decided to go to the holy land of the Buddha and obtain a better copy of these texts. He talked four other monks – Hwuy-king, Tao-ching, Hwuy-ying and Hwuy-wei – into joining him. This group was later joined by another group of five monks at the emporium of Chang-yih, further along in their journey. Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) was in Fa-Hien’s time a part of the Later Qin state ruled by Yao Xing (r. 394-416 CE). It was during his reign that Buddhism first received official state support in China.

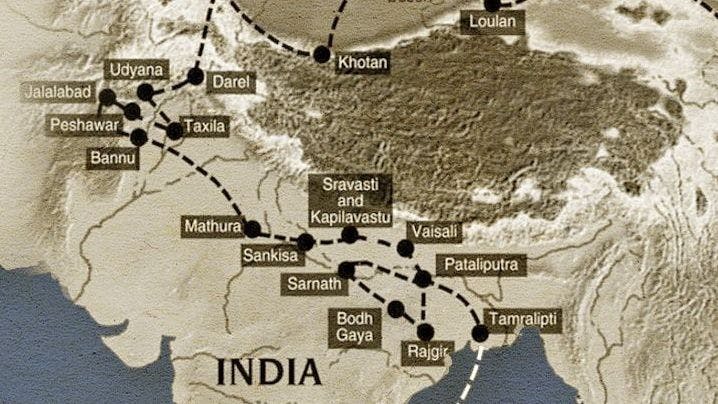

Fa-Hien made his way from Chang’an to the Kingdoms of Loulan and Khotan (in present-day Xinjiang province, China). In Khotan, a lord of the country lodged Fa-Hien and the other monks comfortably in a Mahayana monastery called Gomati. While three men from the group set out in advance for their next destination, Fa-Hien and the others stayed in Khotan for three months to see a chariot-procession that he describes in vivid detail in his writings:

“At a distance of three or four li (Chinese mile) from the city, they made a four-wheeled image car, more than thirty cubits high, which looked like the great hall (of a monastery) moving along. The seven precious substances [i.e., gold, silver, lapis lazuli, rock crystal, rubies, diamonds or emeralds, and agate] were grandly displayed about it... The (chief) image [presumably Sakyamuni] stood in the middle of the car... When (the car) was a hundred paces from the gate, the king put off his crown of state... went out at the gate to meet the image…”

This is from the translation of Fa-Hien’s travelogue by Scottish sinologist James Legge, first published in 1887, titled A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Hsien of Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. It is considered the best English translation to date, and all excerpts presented here are drawn from it.

When the procession was over, the group moved south and halted in K’eeh-cha (probably Skardu in present-day Pakistan). Here, the king was holding a pancha parishad religious conference. Fa-Hien writes that this kingdom had some of the Buddha’s relics, which were in possession of this kingdom.

“There is in the country a spittoon which belonged to Buddha, made of stone, and in colour like his alms-bowl. There is also a tooth of Buddha, for which the people have reared a tope (stupa), connected with which there are more than a thousand monks and their disciples, all students of the Hinayana.”

Fa-Hien made his way towards Northern India, passing through vegetation that was very different from that of the Land of Han (as Fa-Hien referred to China). The only familiar plants he noted were the bamboo, pomegranate and sugarcane. Through their travels, via land and sea, Fa-Hien never failed to write of the dangers the group confronted, although some of these accounts seem exaggerated. For instance, just before entering the Indian subcontinent, Fa-Hien writes:

“There are also among them venomous dragons, which, when provoked, spit forth poisonous winds, and cause showers of snow and storms of sand and gravel. Not one in ten thousand of those who encounter these dangers escapes with his life.”

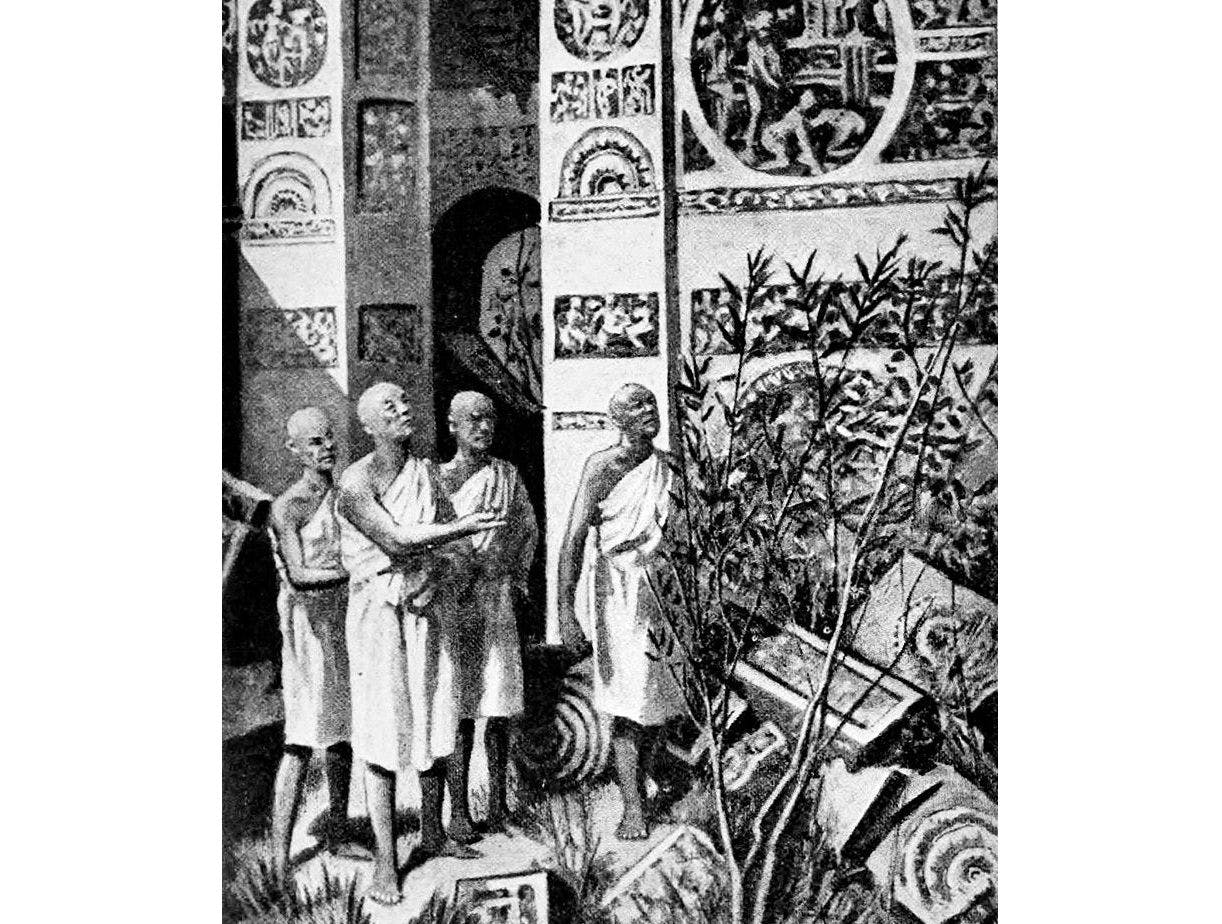

Fa-Hien entered the Indian subcontinent via Udyana (an ancient city in the present-day Swat district of Pakistan). Interestingly, he connects many of the places he visits with stories from the Jatakas , and his account is filled with references to legends around the life of the Buddha. In Udyana, for instance, he mentions a rock with the footprint of the Buddha and a place where the Buddha apparently dried his clothes. Near Taxila, he refers to a place where the Buddha threw down his body to feed a starving tigress.

When the group reached Purushpura (Peshawar), he recollects how the Buddha (571 to 485 BCE) had predicted the birth of a king named ‘Kanishka’, who would build a magnificent stupa at this place. Clearly, by now, legend had taken over and there was an attempt to indicate that the Buddha had travelled even more widely than he actually had. Of Kanishka’s stupa, built in the 2nd century CE in today’s Shaji-ki-Dheri on the outskirts of Peshawar, Fa-Hien writes:

“Of all the topes and temples which (the travellers) saw in our journeyings, there was not one comparable to this in solemn beauty and majestic grandeur. There is a current saying that this is the finest tope in Jambudvipa.”

Just before Fa-Hien crossed the Indus River to go east, he lost one of his companions. The monk Hwuy-king died, possibly from exhaustion. In his last words, Hwuy-king pleaded with his companions to return home, Fa-Hien writes, so that not all of them would die the same way. Fa-Hien was filled with grief, but the group continued its journey.

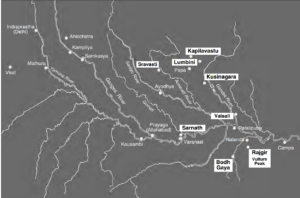

An important city that Fa-Hien visited was Mathura. He writes that all to the south of this is named the ‘Majjhima-desa’ (Middle Kingdom). Writing of life here, he indicates that the city was prosperous, peaceful and that most people seemed to be teetotalers and vegetarians:

“The people are numerous and happy...The king governs without decapitation or (other) corporal punishments...Throughout the whole country the people do not kill any living creature, nor drink intoxicating liquor, nor eat onions or garlic. The only exception is that of the Chandalas. That is the name for those who are (held to be) wicked men, and live apart from others. When they enter the gate of a city or a market-place, they strike a piece of wood to make themselves known, so that men know and avoid them, and do not come into contact with them.”

While in Mathura, Fa-Hien also writes of how, after the death of the Buddha, the kings of the land extended patronage to Buddhist priests:

After Buddha attained to parinirvana, the kings of the various countries and the heads of the Vaisyas built viharas for the priests, and endowed them with fields, houses, gardens, and orchards, along with the resident populations and their cattle, the grants being engraved on plates of metal, so that afterwards they were handed down from king to king, without any one daring to annul them, and they remain even to the present time.”

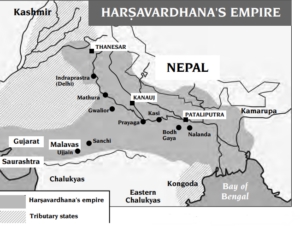

It is worth noting that there is little in Fa-Hien’s writings on general polity or on other faiths. Surprisingly, he doesn’t even mention the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II (r. c. 380 – 415 CE), who would have been at the height of his power during Fa-Hien’s visit.

Fa-Hien writes that he was most excited to visit Kapilavastu (located near India’s border with Nepal, there is more than one contender for this ancient city). He wanted to see the grandeur of the place where the Buddha was born. It turned out to be quite a big disappointment. He writes:

“In it there was neither king nor people. All was mound and desolation. Of inhabitants there were only some monks and a score or two of families of the common people... On the roads people have to be on their guard against white elephants and lions, and should not travel incautiously.”

During his travels within India, Pataliputra (present-day Patna) served as a base. Fa-Hien lived here for three years, witnessed monasteries being built and visited places of significance to the Buddhist faith. Sadly, none of the stupas or monasteries in Patna that Fa-Hien mentions in his writings survives today.

“By the side of the tope of Asoka, there has been made a mahayana monastery, very grand and beautiful; there is also a hinayana one; the two together containing six hundred or seven hundred monks. The rules of demeanour and the scholastic arrangements in them are worthy of observation. Shamans of the highest virtue from all quarters, and students, inquirers wishing to find out truth and the grounds of it, all resort to these monasteries.”

He further wrote that the cities and towns here were the greatest of all in the Middle Kingdom and that the inhabitants were rich and prosperous, and vied with one another in the practice of benevolence and righteousness.

While he travelled to many cities associated with the life of the Buddha - Sravasti, Sarnath, Bodh Gaya, Vaishali, Rajgir and more - Fa-Hien’s main objective in coming to India remained unmet. He had still not found the original Buddhist texts he sought. Across the various kingdoms of North India, he had found masters transmitting the rules orally to one another, but there were no transcriptions, no written copies.

Finally, in Pataliputra, in a Mahayana monastery, he found a copy of the Vinaya Pitaka , containing the Mahasanghika rules — those laid down in the first Great Council, while the Buddha was still in the world. But it was in Sanskrit. So Fa-Hien stayed in Patna for three years, learning Sanskrit and writing out the Vinaya rules.

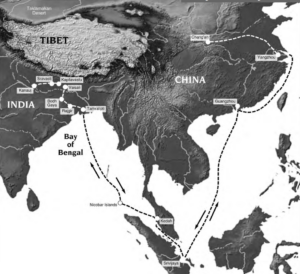

Moving on from Patna, Fa-Hien followed the course of the Ganga eastwards , and reached Champa, and then the port of Tamralipti (in present-day West Bengal). From here, he boarded a large merchant vessel and, after 14 days, reached the country of Singhala (Sri Lanka). He writes about the legends surrounding the history of the island, as he heard them:

“The country originally had no human inhabitants, but was occupied only by spirits and nagas, with which merchants of various countries carried on a trade. When the trafficking was taking place, the spirits did not show themselves. They simply set forth their precious commodities, with labels of the price attached to them; while the merchants made their purchases according to the price; and took the things away.”

In keeping with other legends of the time, Fa-Hien wrote that the Buddha also came to this country in order to transform the wicked nagas . However, historically, there is no record of the Buddha travelling as far as Sri Lanka.

In Singhala, Fa-Hien extolled in detail the richness of the Buddhist influence, as shown in the monasteries, a giant jade statue of the Buddha and their celebration of the holy tooth relic festival. Fa-Hien spent two years in Sri Lanka before finally deciding to return, along a precarious sea route, to China. Today, there is a cave in the district of Kalutara in Sri Lanka named after Fa-Hien. It is believed that he resided there.

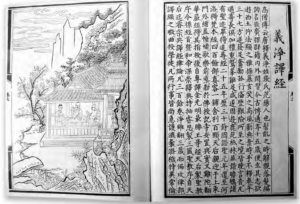

Upon his return home at the age of 77, Fa-Hien spent the next decade – the last decade of his life – translating and editing the many scriptures he had collected, and collating his travelogue. Incidentally, he was helped by an Indian monk named Buddhabhadra, of whom, sadly, very little is known.

Chinese pilgrims and travellers would follow in Fa-Hien’s footsteps for centuries. The most famous were Hiuen Tsang (602-664 CE) and I-tsing (635–713 CE), who penned their own travelogues.

Today a striking statue dedicated to Fa Hien stands near the Huayan Temple in Dataong, China. Though recently erected, it is an apt tribute to the courageous monk who undertook an arduous journey. After all, the temple houses an elaborate library of Buddhist texts, some of which might have been written on the basis of what Fa-Hien put down in words 1600 years ago!

This article is part of our 'The History of India’ series, where we focus on bringing alive the many interesting events, ideas, people and pivots that shaped us and the Indian subcontinent. Dipping into a vast array of material - archaeological data, historical research and contemporary literary records, we seek to understand the many layers that make us.

This series is brought to you with the support of Mr K K Nohria, former Chairman of Crompton Greaves, who shares our passion for history and joins us on our quest to understand India and how the subcontinent evolved, in the context of a changing world.

Find all the stories from this series here.

Handcrafted Home Decor For You

Blue Sparkle Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Handcrafted Tissue Box Cover Sea Green & Indigo Blue (Set of 2)

Scarlet Finely Embroidered Silk Cushion Cover

Sunflower Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Best of Peepul Tree Stories

Faxian ( Chinese : 法顯 ; 337 – c. 422) was a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India, visiting many sacred Buddhist sites in what are now Xinjiang, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka between 399-412 to acquire Buddhist texts . His journey is described in his important travelogue, A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms, Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Xian of his Travels in India and Ceylon in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline . Other transliterations of his name include Fa-Hien , Fa-hian , and Fa-hsien .

- 1 Biography

- 2 Translation of Faxian's work

- 5 References

- 6 Bibliography

- 7 External links

In 399 Faxian set out with nine others to locate sacred Buddhist texts. [2] He visited India in the early fifth century. He is said to have walked all the way from China across the icy desert and rugged mountain passes. He entered India from the northwest and reached Pataliputra . He took back with him Buddhist texts and images sacred to Buddhism. He saw the ruins of the city when he reached Pataliputra .

Faxian's visit to India occurred during the reign of Chandragupta II . He is also renowned for his pilgrimage to Lumbini , the birthplace of Gautama Buddha (modern Nepal ). However, he mentioned nothing about Guptas. Faxian claimed that demons and dragons were the original inhabitants of Sri Lanka . [3]

On Faxian's way back to China, after a two-year stay in Ceylon, a violent storm drove his ship onto an island, probably Java . [4] After five months there, Faxian took another ship for southern China; but, again, it was blown off course and he ended up landing at Mount Lao in what is now Shandong in northern China, 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of the city of Qingdao . He spent the rest of his life translating and editing the scriptures he had collected.

Faxian wrote a book on his travels, filled with accounts of early Buddhism, and the geography and history of numerous countries along the Silk Roads as they were, at the turn of the 5th century CE. He wrote about cities like Magadha, Patliputra, Mathura, city of Kanauj and Middle India. He also wrote that inhabitants of Middle India also eat and dress like China people. He declared Patliputra as a very prosperous city.

He returned in 412 and settled in what is now Nanjing . In 414 he wrote (or dictated) Foguoji ( A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms ; also known as Faxian's Account ). He spent the next decade, until his death, translating the Buddhist sutra he had brought with him from India . [5]

Translation of Faxian's work

The following is the introduction to a translation of Faxian's work by James Legge :

Nothing of great importance is known about Fa-Hien in addition to what may be gathered from his own record of his travels. I have read the accounts of him in the Memoirs of Eminent Monks , compiled in A.D. 519, and a later work, the Memoirs of Marvellous Monks , by the third emperor of the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1403-1424), which, however, is nearly all borrowed from the other; and all in them that has an appearance of verisimilitude can be brought within brief compass Faxian´s route through India His surname , they tell us, was Kung, and he was a native of Wu-yang in P’ing-Yang, which is still the name of a large department in Shan-hsi . He had three brothers older than himself; but when they all died before shedding their first teeth, his father devoted him to the service of the Buddhist society, and had him entered as a Sramanera , still keeping him at home in the family. The little fellow fell dangerously ill, and the father sent him to the monastery , where he soon got well and refused to return to his parents. When he was ten years old, his father died; and an uncle, considering the widowed solitariness and helplessness of the mother, urged him to renounce the monastic life, and return to her, but the boy replied, "I did not quit the family in compliance with my father’s wishes, but because I wished to be far from the dust and vulgar ways of life. This is why I chose monkhood." The uncle approved of his words and gave over urging him. When his mother also died, it appeared how great had been the affection for her of his fine nature; but after her burial, he returned to the monastery. On one occasion he was cutting rice with a score or two of his fellow-disciples when some hungry thieves came upon them to take away their grain by force. The other Sramaneras all fled, but our young hero stood his ground, and said to the thieves, "If you must have the grain, take what you please. But, Sirs, it was your former neglect of charity which brought you to your present state of destitution; and now, again, you wish to rob others. I am afraid that in the coming ages you will have still greater poverty and distress;—I am sorry for you beforehand." With these words he followed his companions into the monastery, while the thieves left the grain and went away, all the monks, of whom there were several hundred, doing homage to his conduct and courage. When he had finished his novitiate and taken on him the obligations of the full Buddhist orders, his earnest courage, clear intelligence, and strict regulation of his demeanor were conspicuous; and soon after, he undertook his journey to India in search of complete copies of the Vinaya-pitaka . What follows this is merely an account of his travels in India and return to China by sea, condensed from his own narrative, with the addition of some marvelous incidents that happened to him, on his visit to the Vulture Peak near Rajagriha . It is said in the end that after his return to China, he went to the capital (evidently Nanking ), and there, along with the Indian Sramana Buddha-bhadra , executed translations of some of the works which he had obtained in India; and that before he had done all that he wished to do in this way, he removed to King-chow (in the present Hoo-pih ), and died in the monastery of Sin, at the age of eighty-eight, to the great sorrow of all who knew him. It is added that there is another larger work giving an account of his travels in various countries. Such is all the information given about our author, beyond what he himself has told us. Fa-Hien was his clerical name, and means "Illustrious in the Law," or "Illustrious master of the Law." The Shih which often precedes it is an abbreviation of the name of Buddha as Sakyamuni, "the Sakya , mighty in Love, dwelling in Seclusion and Silence," and may be taken as equivalent to Buddhist. It is sometimes said to have belonged to "the eastern Tsin dynasty " (A.D. 317-419), and sometimes to "the Sung," that is, the Sung dynasty of the House of Liu (A.D. 420-478). If he became a full monk at the age.... of twenty, and went to India when he was twenty-five, his long life may have been divided pretty equally between the two dynasties.

- Faxian (1886). A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms; being an account by the Chinese monk Fa-Hien of his travels in India and Ceylon, A.D. 399-414, in search of the Buddhist books of discipline . James Legge (trans.). The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Faxian (1877). Record of the Buddhistic Kingdoms . Herbert A Giles (trans.). Trubner & Co., London.

- Chinese Buddhism

- Fa Hien Cave

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- ↑ Li, Xican (2016). "Faxian's Biography and His Contributions to Asian Buddhist Culture: Latest Textual Analysis" . Asian Culture and History . 8 (1): 38. doi : 10.5539/ach.v8n1p38 . Retrieved 16 August 2017 .

- ↑ Jaroslav Průšek and Zbigniew Słupski, eds., Dictionary of Oriental Literatures: East Asia (Charles Tuttle, 1978): 35.

- ↑ The Medical times and gazette, Volume 1 . LONDON: John Churchill. 1867. p. 506 . Retrieved February 19, 2011 . (Original from the University of Michigan)

- ↑ Buswell, Robert E., Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism , Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 297

Bibliography

- Beal, Samuel . 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang . 2 vols. Translated by Samuel Beal. London. 1884. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969. (Also contains a translation of Faxian's book on pp. xxiii-lxxxiii). Volume 1 ; Volume 2 .

- Hodge, Stephen (2009 & 2012), "The Textual Transmission of the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana-sutra" , lecture at the University of Hamburg

- Legge, James 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Hien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline . Oxford, Clarendon Press. Reprint: New York, Paragon Book Reprint Corp. 1965. ISBN 0-486-21344-7

- Rongxi, Li; Dalia, Albert A. (2002). The Lives of Great Monks and Nuns , Berkeley CA: Numata Center for Translation and Research

- Sen, T. (2006). The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing , Education About Asia 11 (3), 24-33

- Weerawardane, Prasani (2009). Journey to the West: Dusty Roads, Stormy Seas and Transcendence , biblioasia 5 (2), 14-18

- Jain, Sandhya, & Jain, Meenakshi (2011). The India they saw: Foreign accounts. New Delhi: Ocean Books.

External links

- Extracts from James Legge's translation

- Original Chinese text, Taisho 2085

- Legge's translation with original Chinese text, T 2085

- Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms , University of Adelaide

- Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms (Complete HTML at web.archive.org) , University of Adelaide

- Faxian; Legge, James. Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms 佛國記 . NTI Buddhist Text Reader . Retrieved 6 January 2015 . Chinese-English bilingual version

- Translators to Chinese

- Pilgrimage accounts

- Chinese Buddhist monks

- Pages using religious biography with multiple nickname parameters

- Articles having different image on Wikidata and Wikipedia

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Imported from Wikipedia

Navigation menu

The Journey of Faxian to India

Between 399 and 414 CE, the Chinese monk Faxian (Fa-Hsien, Fa Hien) undertook a trip via Central Asia to India seeking better copies of Buddhist books than were currently available in China. Although cryptic to the extent that we cannot always be sure where he was, his account does provide interesting information on the conditions of travel and the Buddhist sites and practices he witnessed. For example, he indicates clearly the importance of the seven precious substances for Buddhist worship, the widespread practice of stupa veneration, and his aquaintance with several of the jataka tales about the previous lives of the Buddha Sakyamuni, tales which are illustrated in the paintings at the Dunhuang caves. The extracts below, covering the early part of his journey, are from James Legge, tr. and ed., A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Hien of His Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline (Oxford, 1886), pp. 9-36. I have inserted occasional explanations in brackets, rather than attempt to footnote the text.

------------------

Fa-hien had been living in Ch'ang-gan. Deploring the mutilated and imperfect state of the collection of the Books of Discipline....he entered into an engagement with Hwuy-king, Tao-ching, Hwuy-ying and Hwuy-wei that they should go to India and seek for the disciplinary Rules.

After starting from Ch'ang-gan, they passed through Lung [in eastern Gansu]...and reached the emporium of Chang-yih [north and west of Lanzhou, near the Great Wall]. There they found the country so much disturbed that travelling on the roads was impossible for them. Its king, however, was very attentive to them [and] kept them (in his capital)...

Here they met with Che-yen, Hwuy-keen, Sang-shao, Pao-yun, and Sang-king; and in pleasant association with them, as bound on the same journey with themselves, they passed the summer retreat (of that year [i.e., 400 CE])together, resuming after it their traveling, and going on to T'un-hwang, (the chief town) in the frontier territory of defence extending for about 8o li from east to west, and about 40 from north to south. Their company, increased as it had been, halted there for some days more than a month, after which Fa-hien and his four friends started first in the suite of an envoy, having separated (for a time) from Pao~yun and his associates.

Le Hao, the prefect of T'un-hwang, had supplied them with the means of crossing the desert (before them), in which there are many evil demons and hot winds. (Travellers) who encounter them perish all to a man. There is not a bird to be seen in the air above, nor an animal on the ground below. Though you look all round most earnestly to find where you can cross, you know not where to make your choice, the only mark and indication being the dry bones of the dead (left upon the sand).

After travelling for seventeen days, a distance we may calculate of about 1500 li , (the pilgrims) reached the kingdom of Shen-shen [=?Lou-lan, near Lop Nor], a country rugged and hilly, with a thin and barren soil. The clothes of the common people are coarse, and like those worn in our land of Han, some wearing felt and others coarse serge or cloth of hair;--this was the only difference seen among them. The king professed (our) Law, and there might be in the country more than four thousand monks, who were all students of the Hinayana [Thereavada]. The common people of this and other kingdoms (in that region), as well as the sramans [monks], all practise the rules of India, only that the latter do so more exactly, and the former more loosely. So (the travellers) found it in all the kingdoms through which they went on their way from this to the west, only that each had its own peculiar barbarous speech. (The monks), however, who had (given up the worldly life) and quitted their families, were all students of Indian books and the Indian language. Here they stayed for about a month, and then proceeded on their journey, fifteen days walking to tho north-west bringing them to the country of Woo-e [near Kucha or Karashahr on the northern edge of the Tarim?]. In this also there were more than four thousand monks, all students of the Hinayana. They were very strict in their rules, so that sramans from the territory of Ts-in [i.e., northern China] were all unprepared for their regulations. Fa-hien, through the management of Foo Kung-sun, overseer, was able to remain (with his company in the monastery where they were received) for more than two months, and here they were rejoined by Pao-yun and his friends. (At the end of that time) the people of Woo-e neglected the duties of propriety and righteousness, and treated the strangers in so niggardly a manner that Che-yen, Hwuy-keen, and Hwuy-wei went back towards Kao-ch'ang [Khocho, near Turfan], hoping to obtain there the means of continuing their journey. Fa-hien and the rest, however, through the liberality of Foo Kung-sun, managed to go straight forward in a south-west direction. They found the country uninhabited as they went along. The difficulties which they encountered in crossing the streams and on their route, and the sufferings which they endured, were unparalleled in human experience, but in the course of a month and five days they succeeded in reaching Yu-teen [Khotan].

Yu-teen is a pleasant and prosperous kingdom, with a numerous and flourishing population. The inhabitants all profess our Law, and join together in its religious music for their enjoyment. The monks amount to several myriads, most of whom are students of the Mahyana. They all receive their food from the common store. Throughout the country the houses of the people stand apart like (separate) stars, and each family has a small tope [stupa]reared in front of its door. The smallest of these may be twenty cubits high, or rather more. They make (in the monasteries) rooms for monks from all quarters, the use of which is given to travelling monks who may arrive, and who are provided with whatever else they require.

The lord of the country lodged Fa-hien and the others comfortably, and supplied their wants, in a monastery called Gomati, of the Mahayana school. Attached to it there are three thousand monks, who are called to their meals by the sound of a bell. When they enter the refectory, their demeanour is marked,by a reverent gravity, and they take their seats in regular order, all maintaining a perfect silence. No sound is heard from their alms-bowls and other utensils. When any of these pure men require food, they are not allowed to call out (to the attendants) for it, but only make signs with their hands.

Hwuy-king, Tao-ching, and Hwuy-tah set out in advance towards the country of K'eeh-ch'a; but Fa-hien and the others, wishing to see the procession of images, remained behind for three months. There are in this country four great monasteries, not counting the smaller ones. Beginning on the first day of the fourth month, they sweep and water the streets inside the city, making a grand display in the lanes and byways. Over the city gate they pitch a large tent, grandly adorned in all possible ways, in which the king and queen, with their ladies brilliantly arrayed, take up their residence (for the time).

The monks of the Gomati monastery, being Mahayana students, and held in greatest reverence by the king, took precedence of all the others in the procession. At a distance of three or four li from the city, they made a four-wheeled image car, more than thirty cubits, high, which looked like the great hall (of a monastery) moving along. The seven precious substances [i.e., gold, silver, lapis lazuli, rock crystal, rubies, diamonds or emeralds, and agate] were grandly displayed about it, with silken streamers and canopies harging all around. The (chief) image [presumably Sakyamuni] stood in the middle of the car, with two Bodhisattvas in attendance on it, while devas were made to follow in waiting, all brilliantly carved in gold and silver, and hanging in the air. When (the car) was a hundred paces from the gate, the king put off his crown of state, changed his dress for a fresh suit, and with bare feet, carrying in his hands flowers and incense, and with two rows of attending followers, went out at the gate to meet the image; and, with his head and face (bowed to the ground), he did homage at its feet, and then scattered the flowers and burnt the incense. When the image was entering the gate, the queen and the brilliant ladies with her in the gallery above scattered far and wide all kinds of flowers, which floated about and fell promiscuously to the ground. In this way everything was done to promote the dignity of the occasion. The carriages of the monasteries were all different, and each one had its own day for the procession. (The ceremony) began on the first day of the fourth month, and ended on the fourteenth, after which the king and queen returned to the palace.

Seven or eight li to the west of the city there is what is called the King's New monastery, the building of which took eighty years, and extended over three reigns. It may be 250 cubits in height, rich in elegant carving and inlaid work, covered above with gold and silver, and finished throughout with a combination of all the precious substances. Behind the tope there has been built a Hall of Buddha of the utmost magalficence and beauty, the beams, pillars, venetianed doors, and windows being all overlaid with goldleaf. Besides this, the apartments for the monks are imposingly and elegantly decorated, beyond the power of words to express. Of whatever things of highest value and preciousness the kings in the six countries on the east of the (Ts'ung) range of mountains [probably this means southwestern Xinjiang] are possessed, they contribute the greater portion (to this monastery), using but a small portion of them themselves.

When the processions of images in the fourth month were over, Sang-shao, by himself alone, followed a Tartar who was an earnest follower of the Law, and proceeded towards Kophene [Kabul region?], Fa-hien and the others went forward to the kingdom of Tsze-hoh [?Tashkurgan, ?Baltistan in northern Pakistan], which it took them twenty-five days to reach. Its king was a strenuous follower of our Law, and had (around him) more than a thousand monks, mostly students of the Mahayana. Here (the travellers) abode fifteen days, and then went south for four days, when they found themselves among the Ts'ung-ling mountains, and reached the country of Yu-hwuy, where they halted and kept their retreat. When this was over, they went on among the hills for twenty-five days, and got to K'eeh-ch'a [?Skardu, or a town to the east in Ladak], there rejoining Hwuy-king and his two companions.

It happened that the king of the country was then holding the pancha parishad , that is, in Chinese, the great quinquennial assembly. When this is to be held, the king requests the presence of the sramans from all quarters (of his kingdom). They come (as if) in clouds; and when they are all assembled, their place of session is grandly decorated. Silken streamers and canopies are hung out in it, and waterlilies in gold and silver are made and fixed up behind the places where (the chief of them) are to sit. When clean mats have been spread, and they are all seated, the king and his ministers present their offerings according to rule and law. (The assembly takes place) in the first, second, or third month, for the most part in the spring.

After the king has held the assembly, he further exhorts the ministers to make other and special offerings. The doing of this extends over one, two, three, five, or even seven days; and when all is finished, he takes his own riding-horse, saddles, bridles, and waits on him himself, while he makes the noblest and most important minister of the kingdom mount him. Then, taking fine white woollen cloth, all sorts of precious things, and articles which the sramans require, he distributes them among them, uttering vows at the same time along with all his ministers; and when this distribution has taken place, he again redeems (whatever he wishes) from the monks.

The country, being among the hills and cold, does not produce the other cereals, and only the wheat gets ripe. After the monks have received their annual (portion of this), the mornings suddenly show the hoar-frost, and on this account the king always begs the monks to make the wheat ripen before they receive their portion. There is in the country a spittoon which belonged to Buddha, made of stone, and in colour like his alms-bowl. There is also a tooth of Buddha, for the people have reared a tope, connected with which there are more than a thousand monks and their disciples, all students of the Hinayana. To the east of these hills the dress of the common people is of coarse materials, as in our country of Ts-in, but here also there were among them the differences of fine woollen cloth and of serge or haircloth. The rules observed by the sramans are remarkable, and too numerous to be mentioned in detail. The country is in the midst of the Onion range.

As you go forward from these mountains, the plants, trees, and fruits are all different from those of the land of Han, excepting only the bamboo, pomegranate, and sugar-cane.

From this (the travellers) went westwards towards North India, and after being on the way for a month, they succeeded in getting across and through the range of the Onion mountains. The snow rests on them both winter and summer. There are also among them venomous dragons, which, when provoked, spit forth poisonous winds, and cause showers of snow and storms of sand and gravel. Not one in ten thousand of those who encounter these dangers escapes with his life. The people of the country call the range by the name of 'The Snow mountains.' When (the travellers) had got through them, they were in North India, and immediately on entering its borders, found themselves in a small kingdom called T'o-leih, where also there were many monks, all students of the Hinayana.

In this kingdom there was formerly an Arhat [a disciple of the Buddha who has attained nirvana], who by his supernatural power took a clever artificer up to the Tushita heaven [where bodhisattvas are reborn before appearing on earth as buddhas], to see the height, complexion, and appearance of Maitreya Bodhisattva [the "Buddha of the Future"], and then return and make an image of him in wood. First and last, this was done three times, and then the image was completed, eighty cubits in height, and eight cubits at the base from knee to knee of the crossed legs. On fast-days it emits an effulgent light. The kings of the (surrounding) countries vie with one another in presenting offerings to it. Here it is--to be seen now as of old.

The travellers went on to the south-west for fifteen days (at the foot of the mountains, and) following the course of their range. The way was difficult and rugged, (running along) a bank exceedingly precipitous which rose up there, a hill-like wall of rock, 10,000 cubits from the base. When one approached the edge of it, his eyes became unsteady; and if he wished to go forward in the same direction, there was no place on which he could place his foot; and beneath were the waters of the river called the Indus. In former times men had chiselled paths along the rocks, and distributed ladders on the face of them, to the number altogether of 700, at the bottom of which there was a suspension bridge of ropes, by which the river was crossed, its banks being there eighty paces apart. The (place and arrangements) are to be found in the Records of the Nine Interpreters, but neither Chang K'een [Chang Ch'ien, the Han emissary to the Western Regions] nor Kan Ying [sent west in 88 CE] had reached the spot.

The monks asked Fa-hien if it could be known when the Law of Buddha first went to the east. He replied, 'When I asked the people of those countries about it, they all said that it had been handed down by their fathers from of old that, after the setting up of the image of Maitreya Bodhisattva, there were sramans of India who crossed this river, carrying with them sutras and Books of Discipline. Now the image was set up rather more than 300 years after the nirvana of Buddha, which may be referred to the reign of king P'ing of the Chow dynasty. According to this account we may say that the diffusion of our great doctrines (in the east) began from (the setting up of) this image. If it had not been through that Maitreya, the great spiritual master (who is to be) the successor of the Sakya, who could have caused the "Three Precious Ones" [the precious Buddha, the precious Law, and the precious Monkhood] to be proclaimed so far, and the people of those border lands to know our Law? We know of a truth that the opening of (the way for such) a mystertous propagation is not the work of man; and so the dream of the emperor Ming of Han had its proper cause. [This refers to the belief that a dream of this Han emperor in 61 CE led him to seek out Buddhism and establish it in China.]

After crossing the river, (the travellers) immediately came to the kingdom of Woo-chang [Udyana, north of the Punjab--i.e., Swat in northern Pakistan], which is indeed (a part) of North India. The people all use the language of Central India, 'Central India' being what we should call the 'Middle Kingdom.' The food and clothes of the common people are the same as in that Central Kingdom. The Law of Buddha is very (flourishing in Woo-chang). They call the places where the monks stay (for a time) or reside permanently sangharamas; and of these there are in all 500, the monks being all students of the Hinayana. When stranger bhikshus [i.e., mendicant monks] arrive at one of them, their wants are supplied for three days, after which they are told to find a resting-place for themselves.

There is a tradition that when Buddha came to North India, he came at once to this country, and that here he left a print of his foot, which is long or short according to the ideas of the beholder (on the subject). It exists, and the same thing is true about it, at the present day. Here also are still to be seen the rock on which he dried his clothes, and the place where he converted the wicked dragon. The rock is fourteen cubits high, and more than twenty broad, with one side of it smooth.

Hwuy-king, Hwuy-tah, and Tao-ching went on ahead towards (the place of) Buddha's shadow in the country of Nagara; but Fa-hien and the others remained in Woo-chang, and kept the summer retreat. That over, they descended south, and arrived in the country of Soo-ho-to.

In that country also Buddhism is flourishing. There is in it the place where Sakra [Indra], Ruler of Devas, in a former ages, tried the Bodhisattva, by producing a hawk (in pursuit of a) dove, when (the Bodhisattva) cut off a piece of his own flesh, and (with it) ransomed the dove. [This is the well-known Sibi Jataka, a jataka being a tale relating to an incident involving the Buddha in one of his previous incarnations. The Sibi Jataka is depicted on one of the petroglyphs at Shatial in the Hunza Valley and in several of the caves at Dunhuang.] After Buddha had attained to perfect wisdom , and in travelling about with his disciples (arrived at this spot), he informed them that this was the place where he ransomed the dove with a piece of his own flesh. In this way the people of the country became aware of the fact, and on the spot reared a stupa, adorned with layers of gold and silver plates.

The travellers, going downwards from this towards the east, in five days came to the country of Gandhara, the place where Dharma-vivardhana, the son of Asoka [the Mauryan emperor known as a great patron of Buddhism in the third century BCE], ruled. When Buddha was a Bodhisattva. he gave his eyes also for another man here [another jataka tale]; and at the spot they have also reared a large stupa, adorned with, layers of gold and silver plate The people of the country were mostly students of the Hinayana.

Seven days journey from this to the east brought the travellers to the kingdom of Taxila, which means 'the severed head ' in the language of China. Here, when Buddha was a Bodhisattva, he gave away his head to a man [another jataka tale], and from this circumstance the kingdom got its name.

Going on further for two days to the east, they came to the place where the Bodhisattva threw down his body to feed a starving tigress [the Mahasattva Jataka]. In these two places also large stupas have been built, both adorned with layers of all the precious substances. The kings, ministers, and people. of the kingdoms around vie with one another in making offerings a them. The trains of those who come to scatter flowers and light lamps at them never cease. The nations of those quarters call those (and the other two mentioned before) 'the four great stupas.'

Going southwards from Gandhara, (the travellers) in four days arrived at the kingdom of Purushapura [Peshawar]. Formerly, when Buddha was travelling in this country with his disciples, he said to Ananda, 'After my pari-nirvana, there will be a king named Kanishka [the famous Kushan emperor], who shall on this spot build a stupa. This Kanishka was afterwards born into the world; and (once), when he had gone forth to look about him, S,akra, Ruler of Devas, wishing to excite the idea in his mind, assumed the appearance of a little herd-boy, and was making a stupa right in the way (of the king), who asked what sort of a thing he was making. The boy said, 'I am making a stupa for Buddha. The king said, 'Very good;' and immediately, right over the boy's stupa, he (proceeded to) rear another, which was more than four hundred cubits high, and adorned with layers of all the precious substances. Of all the stupas and temples which (the travellers) saw in their journeyings, there was not one comparable to this in solemn beauty and majestic grandeur. There is a current saying, that this 'is the finest stupa in Jambudvipa'. When the king's stupa was completed, the little stupa (of the boy) came out from its side on the south, rather more than three cubits in height.

Buddha's alms-bowl is in this country. Formerly, a king of Yüeh-shih raised a large force and invaded this country, wishing to carry the bowl away. Having subdued the kingdom, as he and his captains were sincere believers in the Law of Buddha, and wished to carry off the bowl, they proceeded to present their offerings on a great scale. When they had done so to the Three Precious Ones, he made a large elephant be grandly caparisoned, and placed the bowl upon it. But the elephant knelt down on the ground, and was unable, to go forward. Again he caused a four-wheeled waggon to be prepared in which the bowl was put to be conveyed away. Eight elephantd were then yoked to it, and dragged it with their united strength' but neither were they able to go forward. The king knew that the time for an association between himself and the bowl had not yet arrived, and was sad and deeply ashamed of himself. Forthwith he built a stupa at the place and a monastery, and left a guard to watch (the bowl), making all sorts of contributions.

There may be there more than seven hundred monks. When it is near midday, they bring out the bowl, and, along with the common people, make their various offerings to it, after which they take their midday meal. In the evening, at the time of incense, they bring the bowl out again. It may contain rather more than two pecks, and is of various colours, black predominating, with the seams that show its fourfold composition distinctly marked. Its thickness is about the fifth of an inch, and it has a bright and glossy lustre. When poor people throw into it a few flowers, it becomes immediately full, while some very rich people, wishing to make offering of many flowers, might not stop till they had thrown in hundreds, thousands, and myriads of bushels, and yet would not be able to fill it.

Pao-yun and Sang-king here merely made their offerings to the alms-bowl, and (then resolved to) go back. Hwuy-king, Hwuy-'tah, and Tao-ching had gone on before, the rest to Nagara, to make their offerings at (the places of) Buddha's shadow, tooth, and the flat-bone of his skull. (There) Hwuy-king fell ill, and Tao-ching remained to look after him while Hwuy-tah came alone to Purushapura, and saw the others, and (then) he with Pao-yun and Sang-king took their way back to the land of Ts'in. Hwuy-king came to his end in the monastery of Buddha's alms-bowl, and on this Fa-hien went forward alone toward the place of the flat-bone of Buddha's skull.

© 1999 Daniel c. Waugh

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- Fa Hien Faxian 337ce 422ce

Fa-Hien [337 CE - 422 CE]

Fa-Hien was a Chinese pilgrim who visited India during the reign of Chandragupta II on a religious mission. He traveled by foot from China to India and returned by sea route.

This article aims to share the facts related to Fa-Hien’s life for candidates preparing for the IAS Exam .

Information on Faxian visit to India is relevant for Civil Services aspirants under the Indian History part of UPSC Prelims exam.

Given below are the links that give information on the account of various foreign travelers who visited India –

Candidates can know more about other Foreign Envoys who visited India on the linked page.

Fa-Hien [337 CE – 422 CE] PDF Download PDF Here

Fa-Hien / Faxian Visit to India – UPSC Prelims Facts

- Fa-Hien is also known as Faxian was born in AD 337 to Tsang Hi in Pingyang Wuyang, modern Linfen City, Shanxi. Faxian was orphaned at an early age and spent most of his adult life in Buddhist monasteries.

- Faxian was a Chinese monk who left Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) in 399 CE to set forth on an expedition through Central Asia to India, and ultimately Sri Lanka at the age of 62.

- During a visit to Chang’an, he was taken aback by the torn and weathered state of the Books of Discipline (Vinaya Pitakas) which contain the monastic code for Buddhist monks and nuns.

- In 399 CE, Faxian was accompanied by 4 others on a mission to visit the land of the Buddha and search for Buddhist texts.

- He reached Purushapura (Peshawar) and recollected how Buddha had predicted the birth of a king named ‘Kanishka’, who would build a magnificent stupa at this place.

- Fa-Hien made his way towards Northern India and took note of very different vegetation from his own land of Han (China). T he only familiar plants he noted were bamboo, pomegranate, and sugarcane.

- He visited India in the early fifth century during the reign of Chandragupta II and entered here from the northwest and reached Pataliputra. Here, in a Mahayana monastery, he found a copy of the Vinaya Pitaka, containing the Mahasanghika rules written in Sanskrit. Hence, he lived in patliputra for nearly three years , learned Sanskrit, and wrote out the Vinaya rules.

- He traveled to many cities associated with the life of the Buddha – Sravasti, Sarnath, Bodh Gaya, Vaishali, Rajgir, etc and wrote about Taxila, Pataliputra, Mathura, and Kannauj in Middle India.

- An important city that Fa-Hien visited was Mathura . He indicates that the city was prosperous, peaceful and that most people seemed to be teetotalers and vegetarians.

- Fa-Hien is renowned for his pilgrimage to Lumbini, the birthplace of Gautama Buddha.

- He followed the course of the Ganga eastwards, reached Champa and then Tamralipti (was an ancient city in West Bengal)

- He traveled across Pakistan, Nepal, Northern India, and eventually to Sri Lanka, and claimed that demons and dragons were the original inhabitants of Ceylon.

- Faxian spent two years in Sri Lanka and decided to return, along a precarious sea route, to China . Today, there is a cave in the district of Kalutara in Sri Lanka named after Fa-Hien. It is believed that he resided there.

- After he returned home at the age of 77, the next decade until his death, he translated the Buddhist Sutra along with the Indian Sramana Buddha-Bhadra and compiled a travelogue filled with invaluable accounts of what life was like, the places he saw, and the nature of Buddhism at the turn of the 5th century.

- He recorded his observations in a travelogue titled Fo-Kwo-Ki (A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms; also known as Faxian’s Account).

- Faxian died in Jingzhou in China, at the age of eighty-eight.

You can also read about Sir Thomas Roe [1581-1644] a foreign traveler from England.

Check out the following links for assistance in comprehensive preparation of the upcoming UPSC Civil services exams –

Recordings of Faxian

Political and Administration conditions

- Fa-Hien did not record anything specifically about the political condition of India. He did not even mention the name of Chandragupta II during whose reign he visited the country.

- He simply inferred that the administration of the Guptas was liberal, the people enjoyed economic prosperity and the burden of taxes on them was not heavy. Mostly, fines were exacted from the offenders and corporal punishment was avoided and, probably, the death penalty was absent.

- The primary source of income of the state during that time was land revenue and people could move freely from one land to another.

- Monasteries, Sanghas, temples and their property and other religious endowments were free from government taxes.

- The kings and the rich people had built rest-houses where every convenience was provided to the travelers. Also, hospitals were built to provide free medicines to the poor.

- The Fa-Hien account suggests that the administration of the Guptas was benevolent and successful; there was peace and security within the empire.

The Religious Condition

- Based on Fa-Hien’s recordings, people observed tolerance in religious matters because Buddhism and Hinduism both flourished side by side during that time.

- Buddhism was more popular in Punjab, Bengal and the region around Mathura.

- The Hindu religion was more popular in the ‘middle kingdom’ (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and a part of Bengal) which formed the heart of Chandra Gupta II’s dominions.

Visit the following relevant articles for assistance in the preparation for the exam –

The Social Condition

- People during the 5th century i.e. during Fa-hiens’s visit to India were prosperous, happy, liberal and simple in morals.

- Mostly, they were vegetarians and avoided meat and onions and they avoided alcohol and other intoxicants.

- There were houses built for dispensing charity and medicine and gave large donations to temples, monasteries, Sanghas etc.

- The rich people vied with each other in practice of benevolence and righteousness.

- Public morality was high and people were content with their lives.

Other Prominent Records by Faxian in Relation to India

- In the context of his visit to Patliputra, Fa-Hien inferred that there were separate Sanghas both of the Hinayana and Mahayana sects, which provided education to students gathered from all parts of India.

- He was much impressed by chariot-processing that was arranged by people on the eighth day of the second month of every year. The procession carried images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

- Ashoka’s Inscriptions

- About Emperor Ashoka

- Sanchi Stupa and Lion Capital

- Fa-Hien also visited Malwa and praised its climate.

- He described that both internal and external trade of India was in a progressive stage and Sea Voyages were also carried out by Indians.

- On the western sea-coast as described by Faxian, India had ports like Cambay, Sopara, and Baroach whereas on the eastern coast Tamralipti was a famous port. It was this port from where Fa-Hien went to Sri Lanka on an Indian ship.

Revision Points on Faxian Foreign Traveller

- He traveled all over India for more than 13 years.

- Fa-Hien’s visit to India is one of the literary sources to reconstruct the age of Gupta.

- Fa-Hien wrote about India in his book Fo-kwo-ki (Travels of Fa-hien).

- He mentioned about two monasteries in Pataliputra – Mahayana and Hinayana. Other things he noted about Pataliputra was prosperity, an excellent hospital, the existence of rest-houses in large cities and highways, the prevalence of honesty and law, obsolete capital punishment, etc.

- Vegetarianism

- Non-Violence

- Prevalence of caste-system

- Presence of untouchability – Chandalas at the lowest rank

- Existence of slavery

- Remarriage of widows was unfavorable

- Prevalence of Devadasi system

- Fa-Hien mentioned the existence of multiple religions – Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, Buddhism, Jainism etc.

Faxian [337 CE – 422 CE] PDF Download PDF Here

FAQ about Fa-Hien

Who was the ruler when fa-hien visited india, who came first, hiuen tsang or fa-hien.

Aspirants can visit the UPSC Syllabus page to familiarise themselves with the topics generally asked in the exam. For further assistance visit the following links –

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Buddhism Guide

The site for buddhistic culture, history, schools, temples, karma, meditation and many more topics for your religious studies.

The following is from the introduction to a translation of Faxian’s work by James Legge:

- Buddhism in China

Faxian Fa Xian Faxian 法显

Categories: Buddhism

buddha monk

- HEALTH TOPICS |

- COUNTRIES |

Fa-Hien - Encyclopedia

FA-HIEN (fl. A.D. 399-4 1 4), Chinese Buddhist monk, pilgrimtraveller, and writer, author of one of the earliest and most valuable Chinese accounts of India. He started from Changgan or Si-gan-fu, then the capital of the Tsin empire, and passing the Great Wall, crossed the " River of Sand "or Gobi Desert beyond, that home of " evil demons and hot winds," which he vividly describes, - where the only way-marks were the bones of the dead, where no bird appeared in the air above, no animal on the ground below. Arriving at Khotan, the traveller witnessed a great Buddhist festival; here, as in Yarkand, Afghanistan and other parts thoroughly Islamized before the close of the middle ages, Fa-Hien shows us Buddhism still prevailing. India was reached by a perilous descent of " ten thousand cubits " from the " wall-like hills " of the Hindu Kush into the Indus valley (about A.D. 402); and the pilgrim passed the next ten years in the " central " Buddhist realm, - making journeys to Peshawur and Afghanistan (especially the Kabul region) on one side, and to the Ganges valley on another. His especial concern was the exploration of the scenes of Buddha's life, the copying of Buddhist texts, and converse with the Buddhist monks and sages whom the Brahmin reaction had not yet driven out. Thus we find him at Buddha's birthplace on the Kohana, north-west of Benares; in Patna and on the Vulture Peak near Patna; at the Jetvana monastery in Oudh; as well as at Muttra on the Jumna, at Kanauj, and at Tamluk near the mouth of the Hugli. But now the narrative, which in its earlier portions was primarily historical and geographical, becomes mystical and theological; miraclestories and meditations upon Buddhist moralities and sacred memories almost entirely replace matters of fact. From the Ganges delta Fa-Hien sailed with a merchant ship, in fourteen days, to Ceylon, where he transcribed all the sacred books, as yet unknown in China, which he could find; witnessed the festival of the exhibition of Buddha's tooth; and remarked the trade of Arab merchants to the island, two centuries before Mahomet. He returned by sea to the mouth of the Yangtse-Kiang, changing vessels at Java, and narrowly escaping shipwreck or the fate of Jonah.

Fa-Hien's work is valuable evidence to the strength, and in many places to the dominance, of Buddhism in central Asia and in India at the time of the collapse of the Roman empire in western Europe. His tone throughout is that of the devout, learned, sensible, rarely hysterical pilgrim-traveller. His record is careful and accurate, and most of his positions can be identified; his devotion is so strong that it leads him to depreciate China as a " border-land," India the home of Buddha being the true " middle kingdom " of his creed.

See James Legge, Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms, being an account by the Chinese Monk Fd-hien of his travels in India and Ceylon; translated and edited, with map, &c. (Oxford, 1886); S. Beal, Travels of Fah-Hian and SungYun, Buddhist pilgrims from China to India, 400 and 518 A.D., translated, with map, &c. (1869); C. R. Beazley, Dawn of Modern Geography, vol. i. (1897), pp. 478-485.

Encyclopedia Alphabetically

A * B * C * D * E * F * G * H * I * J * K * L * M * N * O * P * Q * R * S * T * U * V * W * X * Y * Z

Advertise Here

- Please bookmark this page (add it to your favorites) - If you wish to link to this page, you can do so by referring to the URL address below.

This page was last modified 29-SEP-18 Copyright © 2021 ITA all rights reserved.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

- AAS-in-Asia Conference July 9-11, 2024

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The travel records of chinese pilgrims faxian, xuanzang, and yijing: sources for cross-cultural encounters between ancient china and ancient india.

The spread of Buddhist doctrines from India to China beginning sometime in the first century CE triggered a profusion of cross-cultural exchanges that had a profound impact on Asian and world history. The travels of Buddhist monks and pilgrims and the simultaneous circulation of religious texts and relics not only stimulated interactions between the Indian kingdoms and various regions of China, but also influenced people living in Central and Southeast Asia. Indeed, the transmission of Buddhist doctrines from India to China was a complex process that involved multiple societies and a diverse group of people, including missionaries, itinerant traders, artisans, and medical professionals. 1

Chinese pilgrims played a key role in the exchanges between ancient India and ancient China. They introduced new texts and doctrines to the Chinese clergy, carried Buddhist paraphernalia for the performance of rituals and ceremonies, and provided detailed accounts of their spiritual journeys to India. Records of Indian society and its virtuous rulers, accounts of the flourishing monastic institutions, and stories about the magical and miraculous prowess of the Buddha and his disciples often accompanied the descriptions of the pilgrimage sites in their travel records. In fact, these travel records contributed to the development of a unique perception of India among members of the Chinese clergy. For some, India was a sacred, even Utopian, realm. Others saw India as a mystical land inhabited by “civilized” and sophisticated people. In the context of Chinese discourse on foreign peoples, who were often described as uncivilized and barbaric, these accounts significantly elevated the Chinese perception of Indian society. 2

Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing were among hundreds of Chinese monks who made pilgrimages to India during the first millennium CE. The detailed accounts of their journeys make them more famous than others. These travel records are important historical resources for several reasons. First, they provide meticulous accounts of the nature of Buddhist doctrines, rituals, and monastic institutions in South, Central, and Southeast Asia. Second, they contain vital information about the social and political conditions in South Asia and kingdoms situated on the routes between China and India. Third, they offer remarkable insights into cross-cultural perceptions and interactions. Additionally, these accounts throw light on the arduous nature of long-distance travel, commercial exchanges, and the relationship between Buddhist pilgrims and itinerant merchants. 3

Faxian (337?–422?)

Faxian was one of the first and perhaps the oldest Chinese monk to travel to India. In 399, when he embarked on his trip from the ancient Chinese capital Chang’an (present-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province), Faxian was more than sixty years old. By the time he returned fourteen years later, the Chinese monk had trekked across the treacherous Taklamakan desert (in present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China), visited the major Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India, traveled to Sri Lanka, and survived a precarious voyage along the sea route back to China (Map 1). 4

The opening passage of Faxian’s A Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms tells us that the procurement of texts related to monastic rules (i.e., Vinaya ) was the main purpose of his trip to India. In addition to revealing the intent of his trip, the statement also underscores the need for this crucial Buddhist literature in contemporary China. In the third and fourth centuries, a number of important Buddhist texts, including the Lotus Sutra , had been translated into Chinese. Although a few Vinaya texts were available to Faxian, the growing Buddhist community in China was aware of the paucity of these texts essential for the establishment and proper functioning of monastic institutions. 5

Faxian was about 77 years old when he reached the Chinese coast. His A Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms was the first eyewitness account of the Buddhist practices and pilgrimage sites in Central and South Asia written in Chinese.

As he proceeded westward toward India, Faxian encountered the multiethnic societies of Central Asia. In Loulan, for example, he saw people who dressed like the Chinese but followed the customs of India. The local Buddhist clergy, according to him, read Indian books and practiced speaking Indian language. Faxian also describes the famous oasis city of Khotan on the southern rim of the Taklamakan as an important Buddhist center in the region. “Throughout the country,” he writes, “the houses of the people stand apart like (separate) stars, and each family has a small tope (i.e., pagoda) reared in front of its door. The smallest of these may be twenty cubits high, or rather more. They make (in monasteries) rooms for monks from all quarters, the use of which is given to traveling monks who may arrive, and are provided with whatever else they require.” 6

It quickly becomes clear from Faxian’s travel record that he wanted to highlight Buddhist practices at the sites he visited. Thus, his account includes the description of local Buddhist monasteries, the approximate number of Buddhist monks in the region, the teachings and rituals practiced by them, and the Buddhist legends associated with some of these sites. Near the city of Taxila (in the present-day northwestern region of Pakistan), for instance, he points out that this was the site where the Buddha, during one of his previous lives, had offered his body to a starving tigress. He describes the conception of the Buddha at Kapilavastu, his birth in a garden in Lumbini, and the attainment of nirvana at Kuśinagara (see Map 2).

The veneration of the relics of the Buddha in Central and South Asia is also detailed throughout the narrative. In Peshawar, for instance, the Chinese monk witnessed the rituals associated with the worship of the Buddha’s alms-bowl. Then in Sri Lanka, he describes the elaborate ceremony overseen by the local ruler to venerate the Buddha’s tooth. These records of relic veneration contributed to the development of similar ceremonies in China. They also triggered a demand for the bodily remains and other objects associated with the life of Śākyamuni Buddha. In fact, the demand for Buddhist relics and ritual items in China resulted in the formation of a unique network through which Buddhist doctrines and ritual items circulated between South and East Asia. This network also fostered a relationship of mutual benefit for Buddhist monks and itinerant traders. While Buddhist monks often hitchhiked on merchant caravans or ships, long-distance traders profited from the creation of new demands for commodities associated with Buddhist rituals. Furthermore, Buddhist monasteries provided accommodation and health care to the long-distance traders, many of whom reciprocated by giving donations to the monastic communities. 7

Sometime in 408 or 409, Faxian reportedly traveled on a mercantile ship from the port of Tamralipti, in eastern India, to Sri Lanka. After about two years’ stay at the island, Faxian again boarded a seagoing vessel to return to China through Southeast Asia. Faxian’s narrative of his voyage on the mercantile vessels, albeit marked by near-catastrophic experiences due to the ravages of the sea, demonstrates the above-mentioned relationship between Buddhist monks and itinerant traders as well as the existence of maritime trading channels linking the coastal regions of India and China. It is also evident from Faxian’s account that maritime travel between southern Asia and China was perilous and the navigational techniques extremely rudimentary.

Faxian was about 77 years old when he reached the Chinese coast. His A Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms was the first eyewitness account of the Buddhist practices and pilgrimage sites in Central and South Asia written in Chinese. It was no doubt immensely popular among the contemporary Chinese clergy, many of whom considered India as a holy land. This unique perception of India among the members of the Chinese clergy and their feeling of melancholy because they lived in the borderland, far removed from the sites frequented by the Buddha, can be discerned in Faxian’s work. 8 Daozheng, one of the Chinese monks who accompanied Faxian, was so moved by the Buddhist sites and monastic institutions in India that he decided not to return to China. “From now until I attain Buddhahood,” Daozheng is supposed to have remarked, “I wish that I not be reborn in the borderland.” 9

Faxian’s account seems to have contributed to the formation of the Chinese perception of India as a sophisticated and culturally advanced society. In the sixth century, Li Daoyuan (d. 527) in his commentary on the third-century work Shui jing ( The Water Classic ) gives the following account of Middle India (referred to as “Madhyade´sa”) 10 based on Faxian’s A Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms:

From here (i.e., Mathura) to the south all [the country] is Middle India (Madhyadeśa). Its people are rich. The inhabitants of Madhyade´sa dress and eat like people in China. 11

This statement in the context of Chinese discourse on foreign societies, where eating habits and manner of clothing were usually associated with the sophistication of a non-Chinese culture, indicates the unique status of the Indians in the Chinese world order. This perception of India as a civilized society persisted until the tenth century, kindled through the reports of later Chinese pilgrims and the works of Chinese clergy that highlighted the erudition of Indian people and the complexity of their society and cultural traditions.

Xuanzang (600?–64)

Xuanzang was a leading Indophile of ancient China. The Chinese monk not only promoted Buddhist doctrines and the perception of India as a holy land through his writings, he also tried to foster diplomatic exchanges between India and China by lobbying his leading patrons, the Tang rulers Taizong (reigned 626–49) and Gaozong (reigned 649–683). In fact, the narrative of his pilgrimage to India, The Records of the Western Regions Visited During the Great Tang Dynasty , 12 was meant for his royal patrons as much as it addressed the contemporary Chinese clergy. Thus, Xuanzang’s work is significant both as an account of religious pilgrimage and as a historical record of foreign states and societies neighboring Tang China. In fact, in the work Xuanzang comes across both as a pious pilgrim and as a diplomat for Tang China. 13

By the time Xuanzang embarked on his trip to India in 627 (see Map 3), monastic institutions and Buddhist doctrines had taken deep roots in China. Almost all basic Buddhist texts had been translated into Chinese. Indigenous works explaining the teachings of the Buddha within the context of existing Daoist and Confucian ideas were being produced in large numbers, and Chinese schools of Buddhism such as the Tiantai had started emerging. The influence of Buddhism extended from the mortuary beliefs and artistic traditions of the Chinese to the political sphere. Additionally, China was becoming an important center for Buddhist learning outside southern Asia, from where the doctrines were transmitted to Korea, Japan, and other neighboring kingdoms.

Xuanzang set out on his pilgrimage to India without formal authorization from the Tang court. His illegal departure from China may have been one of the reasons why Xuanzang deliberately sought audience with important foreign rulers in Central and South Asia.

Born sometime around 600 CE, Xuanzang was ordained at the age of twenty. Like other Chinese pilgrims, one of Xuanzang’s main reasons to undertake the arduous journey to India was to visit its sacred Buddhist sites. Dissatisfied with the translations of Indian Buddhist texts available in China, Xuanzang also wanted to procure original works and learn the doctrines directly from Indian teachers. He expresses his frustration with the translations of Buddhist works available in China in the following way: “Though the Buddha was born in the West,” he writes, “his Dharma has spread to the East. In the course of translation, mistakes may have crept into the texts, and idioms may have been misapplied. When words are wrong, the meaning is lost, and when a phrase is mistaken, the doctrine becomes distorted.” 14 The success of Xuanzang’s mission is evident not only from the 657 Buddhist texts he brought back with him, but also from the quality of translations he undertook. In fact, he is considered one of the three best translators of Buddhist texts in ancient China.

Xuanzang set out on his pilgrimage to India without formal authorization from the Tang court. His illegal departure from China may have been one of the reasons why Xuanzang deliberately sought audience with important foreign rulers in Central and South Asia. He may have thought that the support from these rulers would make his travels in foreign lands and his ultimate return to China free of bureaucratic intrusions. Alternatively, perhaps, he wanted Emperor Taizong, the principal audience of his work, to appreciate the personal and intimate contacts he made with powerful rulers in Central and South Asia. His account thus provides rare insight into the political, diplomatic and religious activities undertaken by contemporary rulers in Central and South Asia.

Like Faxian, Xuanzang takes note of the Indic influences on Central Asian kingdoms. He reports, for example, that the people of Yanqi (Agni), Kuchi (Kucha), and Khotan used modified versions of Indic script. Also similar to Faxian, Xuanzang narrates, although in more detail, the Buddhist legends and miracles associated with the sites he visited and the Buddhist relics he saw. In addition, the perilous nature of long-distance travel between India and China experienced by Faxian is also evident in the work of Xuanzang. However, the most noteworthy aspects of his account are the general discussions of India presented in fascicle two of The Records of the Western Regions and the details of the Chinese monk’s interaction with the Indian ruler Harsavardhana that appear in fascicle five.

Xuanzang begins fascicle two with a discussion of the names for India appearing in various Chinese records. He concludes by stating that the correct Chinese term for India should be Yindu, a name that is still in use in China. Next, the Chinese monk explains the geography and climate, the measurement system, and the concept of time in India. Xuanzang then provides a glimpse of urban life and architecture and narrates in detail the existing caste system, the educational requirements for the Brahmins, the teaching of Buddhist doctrines, legal and economic practices, social and cultural norms, and the eating habits of the natives, and lists the natural and manufactured products of India.