Just added to your cart

Free Shipping over $49

Phish Chicago 2023 Fall Tour Poster

Adding product to your cart

Lot poster created for Phish's October 2023 3-night run in Chicago, IL. Inspired by Phish's classic song, Ocelot, and the Chicago Bulls. Original art by Taylor Swope. Signed and individually numbered out of 100 limited edition prints. • 12" x 18" print on 13" x 19" with 1/2" margin • Printed glossy on White 11 pt Futura 100# dull cover card stock • Digitally signed and numbered series of 100 • Shipped in an acid free clear poly bag inside a 3" diameter cardboard tube

- Share Share on Facebook

- Tweet Tweet on Twitter

- Pin it Pin on Pinterest

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection.

Free standard shipping on all orders over $150

- Women's Apparel

- Women's Tanks & T's

- Women's Hoodies & Sweatshirts

- Women's Skirts & Dresses

- Women's Pants & Shorts

- Women's Sweaters & Jackets

- Women's Flannels

- Women's Socks & Slippers

- Men's Apparel

- Men's T's & Tanks

- Men's Longsleeves

- Men's Flannels

- Men's Hoodies & Sweatshirts

- Men's Sweaters

- Men's Shorts

- Men's Button Downs

- Men's Socks

- Accessories

- Purses, Totes & Fanny Packs

- Hats, Gloves & Scarves

- Necklaces & Pendants

- Grateful Dead Jewelry

- Hair Accessories

- Bath, Body & Face

- Handmade Soaps

- Facial Care

- Moisturizers

- Baby Apparel

- Baby One Pieces

- Baby Shorts & Leggings

- Toddler Apparel

- Toddler T's

- Toddler Shorts & Leggings

- Toddler Hoodies

- Youth Apparel

- Youth Shorts & Leggings

- Youth Hoodies

- Kid's Sunglasses

- Kid's Hats & Gloves

- Kid's Decor

- Stuffed Animals

- Woven Blankets

- Fleece Blankets

- Kitchen Decor & Dishes

- Sage & Incense

- Mobiles & Chimes

- Vintage Housewares

- Vintage Pyrex

- Vintage Glassware

- Vintage Platters & Bowls

- Vintage Decorative Glass

- Vintage Stoneware

- Vintage Plates

- Vintage Pitchers, Coffee Pots & Teapots

- Vintage Sold Items

- Holiday Decor 🎄

- Christmas Tree Skirts

- Holiday Ornaments

- Holiday Garlands

- Grateful Dead Holiday Decor

- Holiday Blankets

- Collars, Leashes & Harnesses

- Pet Bow Ties

- Greeting Cards

- Grateful Dead Cards

- Inspired-by-Phish Cards

- Birthday Cards

- Baby & Parent Cards

- Friendship Cards

- Thank You Cards

- Wedding Cards

- Holiday Cards

- Grateful Dead Stickers

- Phish Stickers

- Hippie Stickers

- Dog & Cat Stickers

- New York Stickers

- Sticker Sheets

- Sun Catcher Decals

- Vintage Grateful Dead Memorabilia

- Cake Toppers

- Fanny Packs

- Grateful Dead Tarot

- Sale Rack Super Deals

- Deals for Women

- Deals for Men

- Deals for Kids

- Deals for Home

- Deals for Pets

- Founder's Story

- Founder's Thoughts

- Learn About Licensing

- Recommended Books

- Hippie History

- Grateful Dead

- Sign Newslettter

- Where to find us

- Register / Login

Your cart is empty

Start with one of these collections:

Popular collections

Description.

Lot poster created for Phish's October 2023 three night run in Chicago, IL. Inspired by Phish's song, Ocelot, and a classic Chicago Bulls poster. Design by Taylor Swope. Digitally signed and individually numbered out of 100 limited edition prints. • 12" x 18" print on 13" x 19" with 1/2" margin • Printed glossy on White 11 pt Futura 100# dull cover card stock • Digitally signed and numbered series of 100 • Shipped in an acid free clear poly bag inside a 3" diameter cardboard tube • Phish inspired

Chicago 2023 Fall Tour Poster

Free shipping on orders over $150

Adding product to your cart

Customer reviews

You might like, let's be friends.

Signup and get 10% off your first purchase

By completing this form, you are signing up to receive our emails and can unsubscribe at any time

Availability

Phish 2023 Posters Signed by the Band up for Auction

Article contributed by the mimi fishm… | published on wednesday, october 25, 2023.

The Mimi Fishman Foundation has unveiled an exclusive online charity auction featuring limited-edition tour posters from Phish's 2023 shows. Each numbered poster is autographed by the entire Phish ensemble: Trey Anastasio, Mike Gordon, Jon Fishman, and Page McConnell.

🔗 Explore the auction and secure a piece of music history: Mimi Fishman Foundation Auction

Auction ends on November 14, 2023. Don't miss out!

LATEST ARTICLES

Be A Part Of The Grateful Web

Check us out on facebook.

Grateful Web

Progressive jam giants Umphrey's McGee‘s return to Las Vegas for the seventh installment of the massively popular UMBowl production was marked once again by a stand-out tour closing dual evening extravaganza where all stops were pulled out and the power given directly to the fans, for better or for worse.

On June 24, Round Records & ATO Records will release GarciaLive Volume Six: July 5, 1973 – Jerry Garcia & Merl Saunders, the latest installment of the celebrated GarciaLive archival series. The three-CD set was recorded at the 200 capacity Lion’s Share club formerly located in the small town of San Anselmo, CA, just 20 miles north of San Francisco. The performance features Jerry Garcia performing with friend, mentor and legendary keyboardist/vocalist Merl Saunders. The duo is joined by drummer Bill Vitt and bassist John Kahn, who soon became a lifelong Garcia collaborator.

COPYRIGHT © 1995 - 2024 GRATEFUL WEB, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

- Phish Setlists

- Guest Appearances

- Upcoming Shows

- Largest Gaps

- Song Histories

- Discography

- The Man Who Stepped Into Yesterday

- Dinner and a Movie Episodes

- A Cappella Chart

- Bustout Chart

- Debut Chart

- Guest Chart

- LivePhish Tracks Chart

- Makisupa Keyword Chart

- Narration Chart

- Secret Language Language Chart

- Song Totals Chart

- Tease Chart

- Tease Timings

- Tour/Show Openers Chart

- 20+ Minute Jam Chart

- Longest Versions Chart

- Acoustic Trey Chart

- Side Project 20+ Min Jam Chart

- Side Project Debuts

- Fan Reviews

- Archived Reviews

- Phish.net Timeline

- Phish.net History in Screenshots

- Confirming Your Account

- Phish.net Technologies

- Random Setlist

- Trey's Notebook

SURRENDER TO THE FLOW FALL 2023 25TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

[Courtesy of Christy Articola, one of the Phish community's most generous and gracious fans over the course of twenty-five years, and the Editor and Publisher of STTF. Do not miss user @farmose (formerly @fad_albert )'s "Horoscopes" in this STTF! -Ed.]

Here is Surrender to the Flow' s Fall Tour 2023 issue ! ( www.gum.co/sttf80 )!

It's our 25th Anniversary issue and it's hard to believe---but amazing for us to contemplate---that we have been putting this magazine out to Phish fans for two and a half decades! We are so thankful for your support and readership, and we think you're really going to love this one.

This issue is full of good stuff for you! It includes information about this year's Fall Tour 2023 in Nashville, Dayton, and Chicago---where to eat, things to do, and things you need to know about each area and venue. You can read reviews of the second half of Summer Tour 2023 in this one, too.

Further, we offer articles on a variety of interesting topics that we know you'll just love and so much more, including articles about a new podcast, a new Phish-fan-focused book, a documentary with a Phish-based soundtrack, and more! And this issue also includes our regular features like recipes, My First Show, My Favorite Jam Ever, 20 Years Later, Phish Changed My Life, Everybody Loves Statistics , horoscopes, Celebrations , fan fiction, a puzzle, and other things we think you'll enjoy.

It's free to download, but we also accept donations if you feel so inclined.

Please check out this issue and tell your friends, and have a great time on Fall Tour this year, everyone! Thanks for all your support over these many years.

If you liked this blog post, one way you could "like" it is to make a donation to The Mockingbird Foundation , the sponsor of Phish.net. Support music education for children, and you just might change the world.

Comment by The_Steiner

Comment by markah

Hooray!!! I was hoping there would be a fall tour ed!!! Will there be a hard copy available for a donation to MBF?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Phish.net is a non-commercial project run by Phish fans and for Phish fans under the auspices of the all-volunteer, non-profit Mockingbird Foundation.

This project serves to compile, preserve, and protect encyclopedic information about Phish and their music.

Credits | Terms Of Use | Legal | DMCA

Donate to Mockingbird

Click here to contact us

The Mockingbird Foundation

The Mockingbird Foundation is a non-profit organization founded by Phish fans in 1996 to generate charitable proceeds from the Phish community.

And since we're entirely volunteer – with no office, salaries, or paid staff – administrative costs are less than 2% of revenues! So far, we've distributed over $2 million to support music education for children – hundreds of grants in all 50 states, with more on the way.

- Subscribe to Relix

- Radio Charts

- Livestream Guide

Current Issue Details

Buy Current Issue

Published: 2023/06/27

Phish Outline Fall 2023 Tour Dates

Today, Phish have announced their fall 2023 tour dates. The impending run is slated to begin in early October. It will consist of three multi-night stands, the first of which will occur in Nashville, Tenn., before follow-ups appearances in Dayton, Ohio, and the final string of shows, which will happen in Chicago.

The initial fall tour dates will be held at Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena, shows will occur nightly on October 6, 7, and 8. In continuation of their brisk jaunt, the Trey Anastasio-led jamband will turn up at Wright State University Nutter Center in Dayton, Ohio, for two back-to-back concerts, scheduled for Oct. 10 and 11.

Phish’s final fall tour dates will be Oct. 13, 14 and 15, when the Vermont-based band arrives at the United Center in Chicago. Before their fall jaunt, the group will participate in their forthcoming summer run, slated to begin at Orion Amphitheater in Huntsville, Ala., on July 11 and 12. Read more about Phish’s summer tour here .

A ticket request period is currently underway at tickets.phish.com and ends Monday, July 10, at noon ET. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Saturday, July 15 at 10 a.m. E.T. Specific ticketing information for each show is available at phish.com/tours .

Moreover, travel packages will be available for Nashville and Chicago. Nashville Travel Packages go on sale on July 12 at 11 a.m. E.T./10 a.m. C.T. and Chicago Travel Packages go on sale one hour later at 12 p.m. E.T./11 a.m. C.T. For more info, visit https://phishfall2023.100xhospitality.com/ .

Phish Fall Tour:

6 – Bridgestone Arena – Nashville, Tenn.

7 – Bridgestone Arena – Nashville, Tenn.

8 – Bridgestone Arena – Nashville, Tenn.

10 – Wright State University Nutter Center – Dayton, Ohio

11 – Wright State University Nutter Center – Dayton, Ohio

13 – United Center – Chicago

14- United Center – Chicago

15 – United Center – Chicago

Show No Comments

No Comments comments associated with this post

Note: It may take a moment for your post to appear

- Phish Dive Deep for Night Two at Las Vegas’ Sphere

- Listen: Alex Koford Releases First Self-Produced, Recorded and Mixed Single, “When I Rise”

- Brooklyn Bowl to Host Benefit for Bad Brains’ HR, with Members of Bad Brains, Fishbone, Living Colour and More

- Warren Haynes, Bill Kreutzmann, Devon Allman and More Share Tributes to Dickey Betts

- Visual Splendor: Phish Commence Sphere Residency with Classics

- Listen: Brian Eno Updates David Bowie’s “Get Real” with Nature Sounds

- Listen: Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats Announce Fourth Full-Length Album ‘South of Here’ with “Heartless” Preview

- The String Cheese Incident Unveil The Mexico Incident with Daniel Donato, moe., Chromeo and More

Most Popular

- Most Commented

- Grateful Dead Release 16 Previously Unheard Outtakes, Alternate Versions and Mixes of “Scarlet Begonias,” “Ship Of Fools,” “China Doll” and More

- Blues Traveler and Big Head Todd & The Monsters Revive Blue Monsters Tour for Summer 2024

- Bob Marley’s Sons Detail The Legacy Tour, First Joint Run in Two-Decades

- Listen: Sean Ono Lennon and James McCartney Unveil Collaborative Single “Primrose Hill”

- Daniel Donato’s Cosmic Country Announce National Television Debut on ‘CBS Saturday Sessions’

- Ventura Offers Array of Alternatives to Skull & Roses This Week

- Ringo Starr and His All Starr Band Announce Fall 2024 Tour Dates

- Lettuce Expand 2024 Tour Schedule: John Scofield, Ziggy Marley, BISCOLAND and More

- Report: Dead & Company Cancel West Palm Beach and Tampa Shows

- Willie Nelson, Bob Weir and More to Participate in ‘Biden For President’ Livestream Fundraiser

- SiriusXM Announces Launch of Phish Radio, Jam On Moves to App and Online

- Eric Clapton Releases Politically-Charged “This Has Gotta Stop”

- Thousands of Music Fans Sign Petition to Bring Jam On Back to SiriusXM

- “You Should Fuckin’ Pay Attention”: Chris Robinson Gets Frustrated at Philadelphia Crowd During “Brothers of a Feather” Gig

- Nike Confirms Grateful Dead Sneaker Collaboration, Sets Release Date

- Zach Deputy Responds to His Attendance at DC Trump Rally

- Monthly Contributors

OUR MINISTER

Dr. Joseph Lozovyy was born into a Christian family in Elektrostal, Moscow Region, and was raised in a pastor’s home. From the age of fifteen, he began actively participating in the music ministry of the Baptist Church in Mytishchi, where his father served as a pastor, and also played in the orchestra of the Central Moscow Baptist Church. From 1989, he participated in various evangelistic events in different cities of Moscow Region and beyond. From 1989 to 1992, as a member of the choir and orchestra “LOGOS,” he participated in evangelistic and charitable concerts, repeatedly performing on the stages of the Moscow State Conservatory, the Bolshoi Theatre, and other concert halls in Russia and abroad. In 1992, his family moved to the United States. In 2007, after completing a full course of spiritual and academic preparation, Joseph moved to Dallas, Texas, to engage in church ministry. In 2008, he founded the Russian Bible Church to preach to the Russian-speaking population living in Dallas, Texas.

– Bachelor of Arts in Music (viola) from the Third Moscow Music School named after Scriabin, Russia (1987-1991)

– Master of Theology (Th.M); Dallas Theological Seminary, Texas (1999-2003);

– Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) Hebrew Bible (Books of Samuel): University of Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom (2007).

– Doctoral research (2004-2005) Tübingen, Germany.

– Author of a theological work published in English: Saul, Doeg, Nabal and the “Son of Jesse: Readings in 1 Samuel 16-25, LHBOTS 497 [T&T Clark/Continuum: Bloomsbury Publishing]).

https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/saul-doeg-nabal-and-the-son-of-jesse-9780567027535/

Joseph and his wife Violetta and their son Nathanael live in the northern part of Dallas.

Saul, Doeg, Nabal, and the “Son of Jesse”: Readings in 1 Samuel 16-25: The Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies Joseph Lozovyy T&T Clark (bloomsbury.com)

Joseph, his wife Violetta and their son Nathaniel live in North Dallas, Texas where he continues ministering to Russian-speaking Christians and his independent accademic research.

Published Work

1. bloomsbury:, 2. buy at christian book distributors:, 3. buy on amazon:.

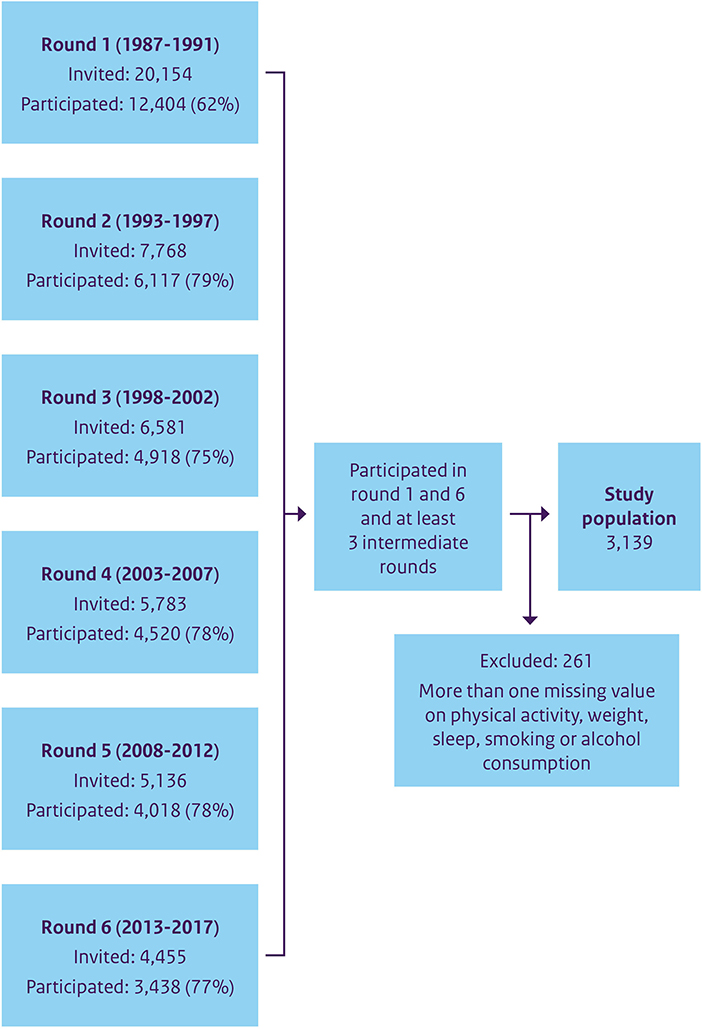

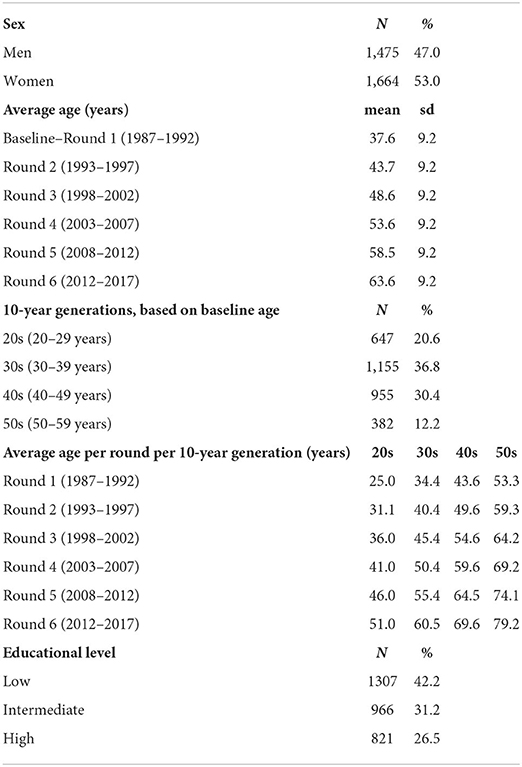

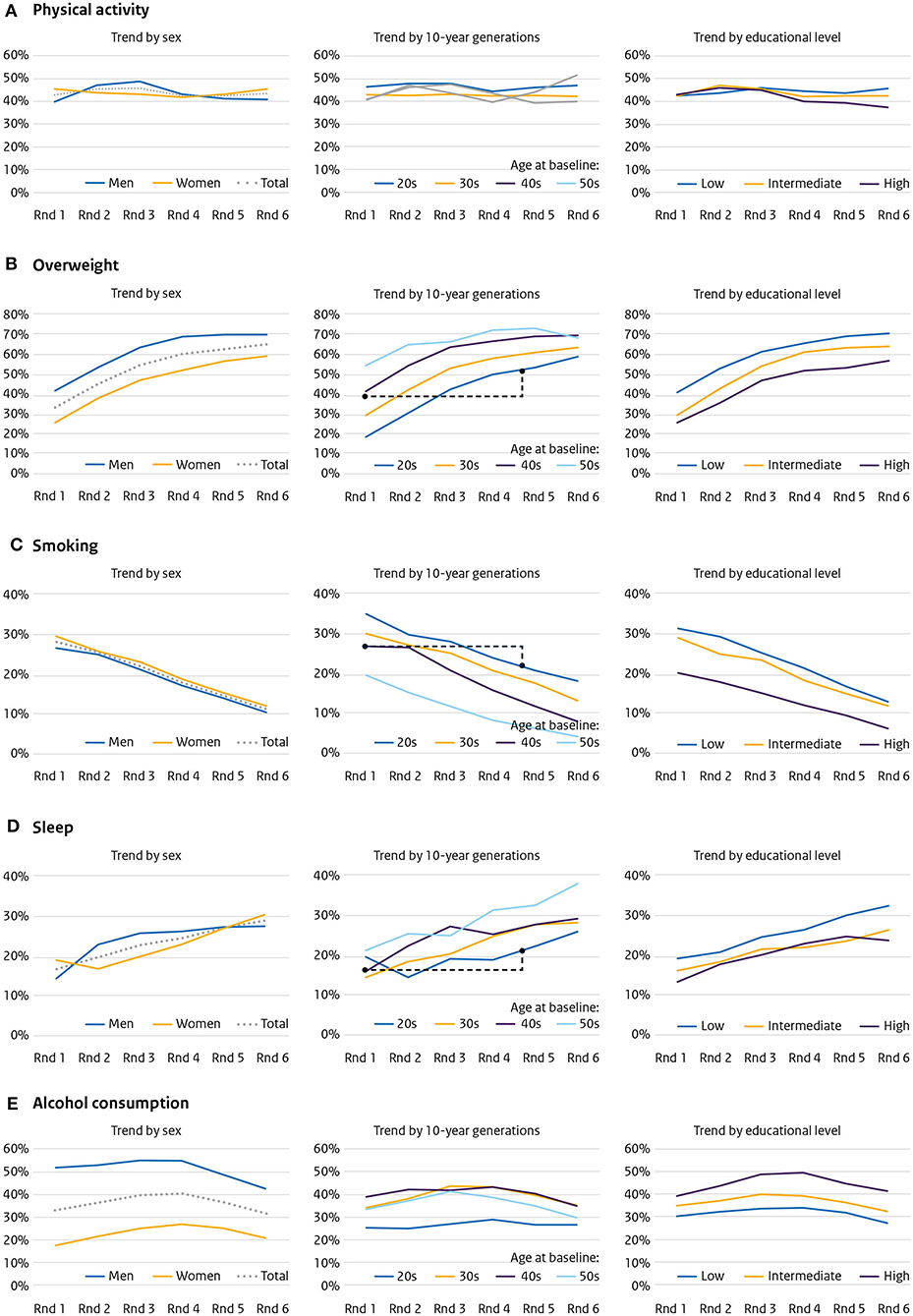

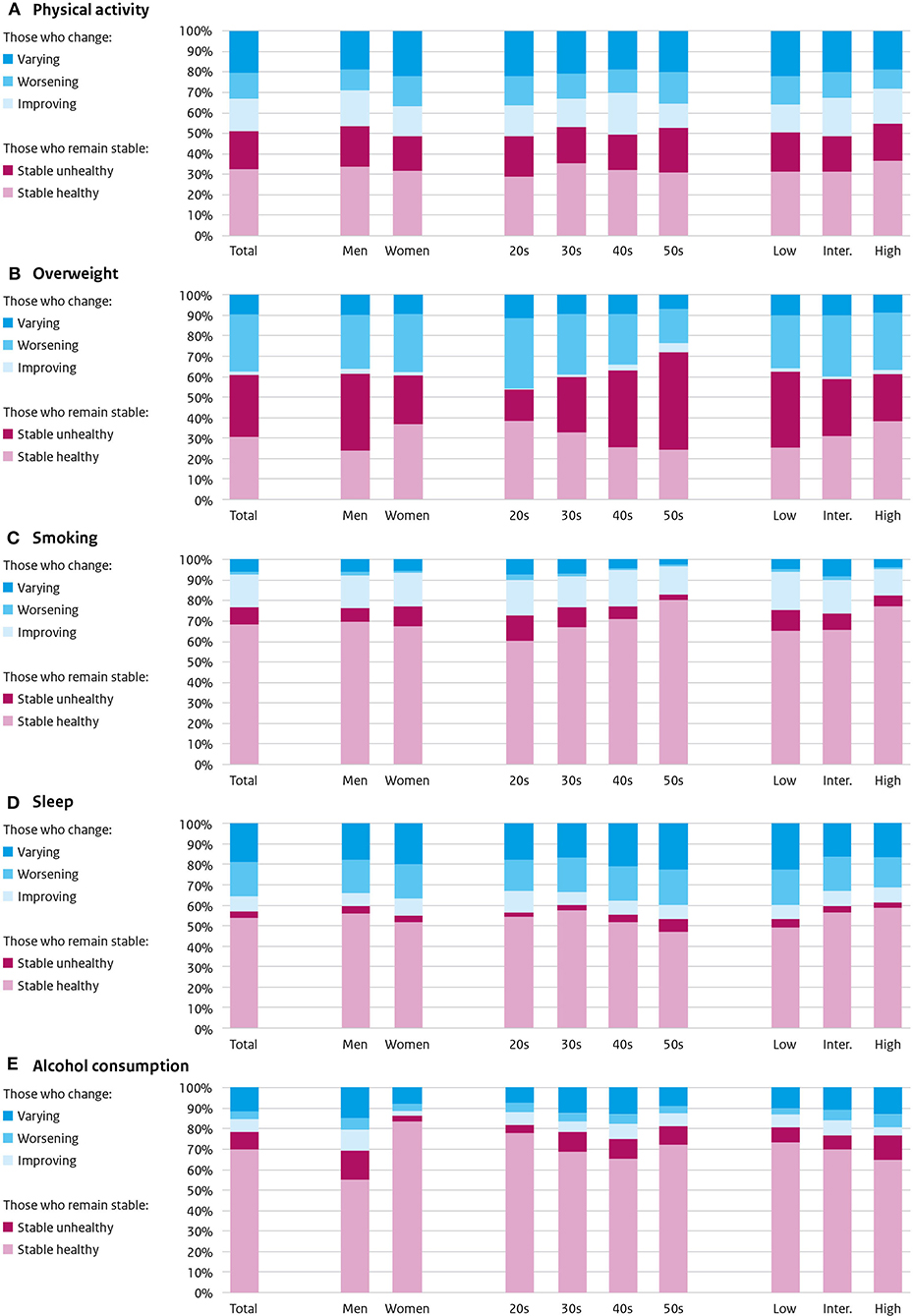

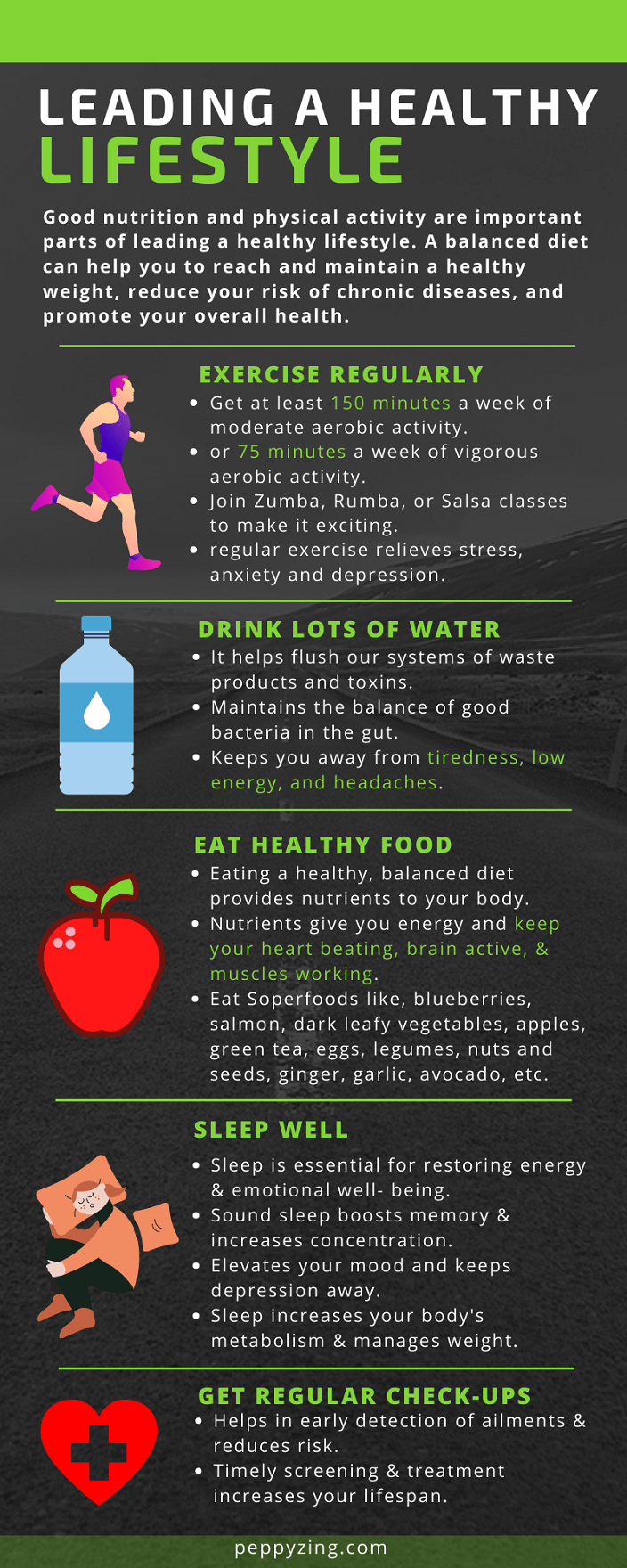

research on healthy lifestyle

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 29 September 2022

A healthy lifestyle is positively associated with mental health and well-being and core markers in ageing

- Pauline Hautekiet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3805-3004 1 , 2 ,

- Nelly D. Saenen 1 , 2 ,

- Dries S. Martens 2 ,

- Margot Debay 2 ,

- Johan Van der Heyden 3 ,

- Tim S. Nawrot 2 , 4 &

- Eva M. De Clercq 1

BMC Medicine volume 20 , Article number: 328 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

16 Citations

61 Altmetric

Metrics details

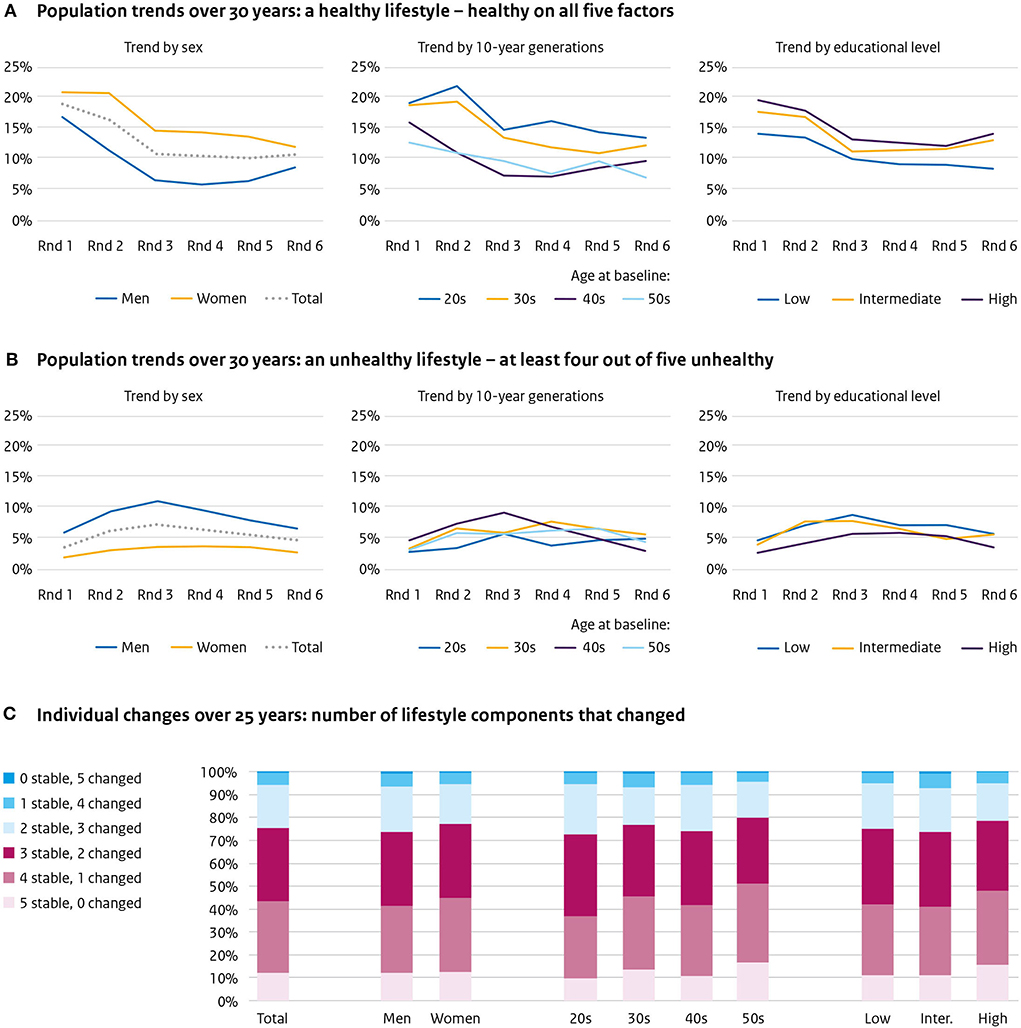

Studies often evaluate mental health and well-being in association with individual health behaviours although evaluating multiple health behaviours that co-occur in real life may reveal important insights into the overall association. Also, the underlying pathways of how lifestyle might affect our health are still under debate. Here, we studied the mediation of different health behaviours or lifestyle factors on mental health and its effect on core markers of ageing: telomere length (TL) and mitochondrial DNA content (mtDNAc).

In this study, 6054 adults from the 2018 Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS) were included. Mental health and well-being outcomes included psychological and severe psychological distress, vitality, life satisfaction, self-perceived health, depressive and generalised anxiety disorder and suicidal ideation. A lifestyle score integrating diet, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI was created and validated. On a subset of 739 participants, leucocyte TL and mtDNAc were assessed using qPCR. Generalised linear mixed models were used while adjusting for a priori chosen covariates.

The average age (SD) of the study population was 49.9 (17.5) years, and 48.8% were men. A one-point increment in the lifestyle score was associated with lower odds (ranging from 0.56 to 0.74) for all studied mental health outcomes and with a 1.74% (95% CI: 0.11, 3.40%) longer TL and 4.07% (95% CI: 2.01, 6.17%) higher mtDNAc. Psychological distress and suicidal ideation were associated with a lower mtDNAc of − 4.62% (95% CI: − 8.85, − 0.20%) and − 7.83% (95% CI: − 14.77, − 0.34%), respectively. No associations were found between mental health and TL.

Conclusions

In this large-scale study, we showed the positive association between a healthy lifestyle and both biological ageing and different dimensions of mental health and well-being. We also indicated that living a healthy lifestyle contributes to more favourable biological ageing.

Peer Review reports

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a healthy lifestyle is defined as “a way of living that lowers the risk of being seriously ill or dying early” [ 1 ]. Public health authorities emphasise the importance of a healthy lifestyle, but despite this, many individuals worldwide still live an unhealthy lifestyle [ 2 ]. In Europe, 26% of adults smoke [ 3 ], nearly half (46%) never exercise [ 4 ], 8.4% drink alcohol on a daily basis [ 5 ] and over half (51%) are overweight [ 5 ]. These unhealthy behaviours have been associated with adverse health outcomes like cardiovascular diseases [ 6 , 7 , 8 ], respiratory diseases [ 9 ], musculoskeletal diseases [ 10 ] and, to a lesser extent, mental disorders [ 11 , 12 ].

Even though the association between lifestyle and health outcomes has been extensively investigated, biological mechanisms explaining these observed associations are not yet fully understood. One potential mechanism that can be suggested is biological ageing. Both telomere length (TL) and mitochondrial DNA content (mtDNAc) are known biomarkers of ageing. Telomeres are the end caps of chromosomes and consist of multiple TTAGGG sequence repeats. They protect chromosomes from degradation and shorten with every cell division because of the “end-replication problem” [ 13 ]. Mitochondria are crucial to the cell as they are responsible for apoptosis, the control of cytosolic calcium levels and cell signalling [ 14 ]. Living a healthy lifestyle can be linked with healthy ageing as both TL and mtDNAc have been associated with health behaviours like obesity [ 15 ], diet [ 16 ], smoking [ 17 ] and alcohol abuse [ 18 ]. Furthermore, as biomarkers of ageing, both TL and mtDNAc have been associated with age-related diseases like Parkinson’s disease [ 19 ], coronary heart disease [ 20 ], atherosclerosis [ 21 ] and early mortality [ 22 ]. Also, early mortality and higher risks for the aforementioned age-related diseases are observed in psychiatric illnesses, and it is suggested that advanced biological ageing underlies these observations [ 23 ].

Multiple studies evaluated individual health behaviours, but research on the combination of these health behaviours is limited. As they often co-occur and may cause synergistic effects, assessing them in combination with each other rather than independently might better reflect the real-life situation [ 24 , 25 ]. Therefore, in a general adult population, we combined five commonly studied health behaviours including diet, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI and physical activity into one healthy lifestyle score to evaluate its association with mental health and well-being and biological ageing. Furthermore, we evaluated the association between the markers of biological ageing and mental health and well-being. We hypothesise that individuals living a healthy lifestyle have a better mental health status, a longer TL and a higher mtDNAc and that these biomarkers are positively associated with mental health and well-being.

Study population

In 2018, 11611 Belgian residents participated in the 2018 Belgian Health Interview Survey (BHIS). The sampling frame of the BHIS was the Belgian National Register, and participants were selected based on a multistage stratified sampling design including a geographical stratification and a selection of municipalities within provinces, of households within municipalities and of respondents within households [ 26 ]. The study population for this cross-sectional study included 6054 BHIS participants (see flowchart in Additional file 1 : Fig. S1) [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Minors (< 18 years) and participants not eligible to complete the mental health modules (participants who participated through a proxy respondent, i.e. a person of confidence filled out the survey) were excluded ( n = 2172 and n = 846, respectively). Furthermore, of the 8593 eligible participants, those with missing information to create the mental health indicators, the lifestyle score or the covariates used in this study were excluded ( n = 1642, 788 and 109, respectively).

For the first time in 2018, a subset of 1184 BHIS participants contributed to the 2018 Belgian Health Examination Survey (BELHES). All BHIS participants were invited to participate except for minors (< 18 years), BHIS participants who participated through a proxy respondent and residents of the German Community of Belgium, the latter representing 1% of the Belgian population. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis until the regional quotas were reached (450, 300 and 350 in respectively Flanders, Brussels Capital Region and Wallonia). These participants underwent a health examination, including anthropological measurements and completed an additional questionnaire. Also, blood and urine samples were collected. Of the 6054 included BHIS participants, 909 participated in the BELHES. Participants for whom we could not calculate both TL and mtDNAc were excluded ( n = 170). More specifically, participants were excluded because they did not provide a blood sample ( n = 91) or because they did not provide permission for DNA research ( n = 32). Twenty samples were excluded from DNA extraction because either total blood volume was too low ( n = 7), samples were clothed ( n = 1) or tubes were broken due to freezing conditions ( n = 12). Twenty-seven samples were excluded because they did not meet the biomarker quality control criteria (high technical variation in qPCR triplicates). This was not met for 3 TL samples, 20 mtDNAc samples and 4 samples for both biomarkers. For this subset, we ended up with a final number of 739 participants. Further in this paper, we refer to “the BHIS subset” for the BHIS participants ( n = 6054) and the “BELHES subset” for the BELHES participants ( n = 739).

As part of the BELHES, this project was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Ghent (registration number B670201834895). The project was carried out in line with the recommendations of the Belgian Privacy Commission. All participants have signed a consent form that was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee.

Health interview survey

The BHIS is a comprehensive survey which aims to gain insight into the health status of the Belgian population. The questions on the different dimensions of mental health and well-being were based on international standardised and validated questionnaires [ 32 ], and this resulted in eight mental health outcomes that were used in this study. Detailed information on each indicator score and its use is addressed in Additional file 1 : Table. S1. Firstly, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) provides the prevalence of psychological and severe psychological distress in the population [ 27 ]. On the total GHQ score, cut-off points of + 2 and + 4 were used to identify respectively psychological and severe psychological distress.

Secondly, we used two indicators for the positive dimensions of mental health: vitality and life satisfaction. Four questions of the short form health survey (SF-36) indicate the participant’s vital energy level [ 28 , 33 ]. We used a cut-off point to identify participants with an optimal vitality score, which is a score equal to or above one standard deviation above the mean, as used in previous studies [ 34 , 35 ]. Life satisfaction was measured by the Cantril Scale, which ranges from 0 to 10 [ 29 ]. A cut-off point of + 6 was used to indicate participants with high or medium life satisfaction versus low life satisfaction.

Thirdly, the question “How is your health in general? Is it very good, good, fair, bad or very bad?” was used to assess self-perceived health, also known as self-rated health. Based on WHO recommendations [ 36 ], the answer categories were dichotomised into “good to very good self-perceived health” and “very bad to fair self-perceived health”.

Fourthly, depressive and generalised anxiety disorders were defined using respectively the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). We identified individuals who suffer from major depressive syndrome or any other type of depressive syndrome according to the criteria of the PHQ-9 [ 37 ]. A cut-off point of + 10 on the total sum of the GAD-7 score was used to indicate generalised anxiety disorder [ 31 ]. Additionally, a dichotomous question on suicidal ideation was used: “Have you ever seriously thought of ending your life?”; “If yes, did you have such thoughts in the past 12 months?”. Finally, the BHIS also includes personal, socio-economic and lifestyle information. The standardised Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the PHQ-9, GHQ-12, GAD-7 and questions on vitality of the SF-36 ranged between 0.80 and 0.90.

Healthy lifestyle score

We developed a healthy lifestyle score based on five different health behaviours: body mass index (BMI), smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption and diet (Table 1 ). These health behaviours were defined as much as possible according to the existing guidelines for healthy living issued by the Belgian Superior Health Council [ 38 ] and the World Health Organisation [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Firstly, BMI was calculated as a person’s self-reported weight in kilogrammes divided by the square of the person’s self-reported height in metres (kg/m 2 ). BMI was classified into four categories: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m 2 ), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m 2 ), overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m 2 ) and obese (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m 2 ). Due to a J-shaped association of BMI with the overall mortality and multiple specific causes of death, obesity and underweight were both classified as least healthy [ 42 ]. BMI was scored as follows: obese and underweight = 0, overweight = 1 and normal weight = 2.

Secondly, smoking status was divided into four categories. Participants were categorised as regular smokers if they smoked a minimum of 4 days per week or if they quit smoking less than 1 month before participation (= 0). Occasional smokers were defined as smoking more than once per month up to 3 days per week (= 1). Participants were classified as former smokers if they quit smoking at least 1 month before the questionnaire or if they smoked less than once a month (= 2). The final category included people who never smoked (= 3).

Thirdly, physical activity was assessed by the question: “What describes best your leisure time activities during the last year?”. Four categories were established and scored as follows: sedentary activities (= 0), light activities less than 4 h/week (= 1), light activities more than 4 h/week or recreational sport less than 4 h/week (= 2) and recreational sport more than 4 h or intense training (= 3). Fourthly, information on the number of alcoholic drinks per week was used to categorise alcohol consumption. The different categories were set from high to low alcohol consumption: 22 drinks or more/week (= 0), 15–21 drinks/week (= 1), 8–14 drinks/week (= 2), 1–7 drinks/week (= 3)and less than 1 drink/week (= 4).

Finally, in line with the research by Benetou et al., a diet score was calculated using the frequency of consuming fruit, vegetables, snacks and sodas [ 43 ]. For fruit as well as vegetable consumption, the frequency was scored as follows: never (= 0), < 1/week (= 1), 1–3/week (= 2), 4–6/week (= 3) and ≥ 1/day (= 4). The frequency of consuming snacks and sodas was scored as follows: never (= 4), < 1/week (= 3), 1–3/week (= 2), 4–6/week (= 1) and ≥ 1/day (= 0). The diet score was then divided into tertiles, in line with the research by Benetou et al. [ 43 ]. A diet score of 0–9 points was classified as the least healthy behaviour (= 0). A diet score ranging from 10 to 12 made up the middle category (= 1), and a score from 13 to 16 was classified as the healthiest behaviour (= 2).

All five previously described health behaviours were combined into one healthy lifestyle score (Table 1 ). The sum of the scores obtained for each health behaviour indicated the absolute lifestyle score. To calculate the relative lifestyle score, each absolute scored health behaviour was given equal weight by recalculating its maximum absolute score to a relative score of 1. The relative lifestyle scores were then summed up to achieve a final continuous lifestyle score, ranging from 0 to 5, with a higher score representing a healthier lifestyle.

Telomere length and mitochondrial DNA content assay

Blood samples were collected during the BELHES and centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm before storage at − 80 °C. After extracting the buffy coat from the blood sample, DNA was isolated using the QIAgen Mini Kit (Qiagen, N.V.V Venlo, The Netherlands). The purity and quantity of the sample were measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. To ensure a uniform DNA input of 6 ng for each qPCR reaction, samples were diluted and checked using the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Europe).

Relative TL and mtDNAc were measured in triplicate using a previously described quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay with minor modifications [ 44 , 45 ]. All reactions were performed on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a 384-well format. Used telomere, mtDNAc and single copy-gene reaction mixtures and PCR cycles are given in Additional file 1 : Text. S1. Reaction efficiency was assessed on each plate by using a 6-point serial dilution of pooled DNA. Efficiencies ranged from 90 to 100% for single-copy gene runs, 100 to 110% for telomere runs and 95 to 105% for mitochondrial DNA runs. Six inter-run calibrators (IRCs) were used to account for inter-run variability. Also, non-template controls were used in each run. Raw data were processed and normalised to the reference gene using the qBase plus software (Biogazelle, Zwijnaarde, Belgium), taking into account the run-to-run differences.

Leucocyte telomere length was expressed as the ratio of telomere copy number to single-copy gene number (T/S) relative to the mean T/S ratio of the entire study population. Leucocyte mtDNAc was expressed as the ratio of mtDNA copy number to single-copy gene number (M/S) relative to the mean M/S ratio of the entire study population. The reliability of our assay was assessed by calculating the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the triplicate measures (T/S and M/S ratios and T, M and S separately) as proposed by the Telomere Research Network, using RStudio version 1.1.463 (RStudio PBC, Boston, MA, USA). The intra-plate ICCs of T/S ratios, TL runs, M/S ratios, mtDNAc runs and single-copy runs were respectively 0.804 ( p < 0.0001), 0.907 ( p < 0.0001), 0.815 ( p < 0.0001), 0.916 ( p < 0.0001) and 0.781 ( p < 0.0001). Based on the IRCs, the inter-plate ICC was 0.714 ( p < 0.0001) for TL and 0.762 ( p < 0.0001) for mtDNAc.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We performed a log(10) transformation of the TL and mtDNAc data to reduce skewness and to better approximate a normal distribution. Three analyses were done: (1) In the BHIS subset ( n = 6054), we evaluated the association between the lifestyle score and the mental health and well-being outcomes (separately). These results are presented as the odds ratio (95% CI) of having a mental health condition or disorder for a one-point increment in the lifestyle score. (2) In the BELHES subset ( n = 739), we evaluated the association between the lifestyle score and both TL and mtDNAc (separately). These results are presented as the percentage difference in TL or mtDNAc (95% CI) for a one-point increment in the lifestyle score. (3) In the BELHES subset ( n = 739), we evaluated the association between the mental health and well-being outcomes and both TL and mtDNAc (separately). These results are presented as the percentage difference in TL or mtDNAc (95% CI) when having a mental health condition or disorder compared with the healthy group.

For all three analyses, we performed multivariable linear mixed models (GLIMMIX; unstructured covariance matrix) taking into account a priori selected covariates including age (continuous), sex (male, female), region (Flanders, Brussels Capital Region, Wallonia), highest educational level of the household (up to lower secondary, higher secondary, college or university), country of birth (Belgium, EU, non-EU) and household type (single, one parent with child, couple without child, couple with child, others). To capture the non-linear effect of age, we included a quadratic term when the result of the analysis showed that both the linear and quadratic terms had a p -value < 0.1. For the two analyses on TL and mtDNAc, we additionally adjusted for the date of participation in the BELHES. As multiple members of one household participated, we added household numbers in the random statement.

Bivariate analyses evaluating the associations between the characteristics and TL, mtDNAc, the lifestyle score or psychological distress as a parameter of mental health and well-being are evaluated based on the same model. The chi-squared tests (categorical data) and t -tests (continuous data) were used to evaluate the characteristics of included and excluded participants. The lifestyle score was validated by creating a ROC curve and calculating the area under the curve (AUC) of the adjusted association between the lifestyle score and self-perceived health. Adjustments were made for age, sex, region, highest educational level of the household, country of birth and household type.

In a sensitivity analysis, to evaluate the robustness of our findings, we additionally adjusted our main models separately for perceived quality of social support (poor, moderate, strong) and chronic disease (suffering from any chronic disease or condition: yes, no). The third model, evaluating the biomarkers with the mental health outcomes, was also additionally adjusted for the lifestyle score.

Population characteristics

The characteristics of the BHIS and BELHES subset are presented in Table 2 . In the BHIS subset, 48.8% of the participants were men. The average age (SD) was 49.9 (17.5) years, and most participants were born in Belgium (79.5%). The highest educational level in the household was most often college or university degree (53.3%), and the most common household composition was couple with child(ren) (37.7%). The proportion of participants in different regions of Belgium, i.e. Flanders, Brussels Capital Region and Wallonia, was respectively 41.1%, 23.3% and 35.6%. For the BELHES subset, we found similar results except for region and education. We noticed more participants from Flanders and more participants with a high educational level in the household. The mean (SD) relative TL and mtDNAc were respectively 1.04 (0.23) and 1.03 (0.24). TL and mtDNAc were positively correlated (Spearman’s correlation = 0.21, p < 0.0001).

We compared (1) the characteristics of the 6054 eligible BHIS participants that were included in the BHIS subset with the 2539 eligible participants that were excluded from the BHIS subset (Additional file 1 : Table S2) and (2) the 739 participants from the BHIS subset that were included in the BELHES subset with the 5315 participants that were excluded from the BELHES subset (Additional file 1 : Table S3). Except for sex and nationality in the latter, all other covariates showed differences between the included and excluded groups. On the other hand, population data from 2018 indicates that the average age (SD) of the adult Belgian population was 49.5 (18.9) with a distribution over Flanders, Brussels Capital Region and Wallonia of respectively 58.2%, 10.2% and 31.6% and that 48.7% were men. The distribution of our sample according to age and sex thus largely corresponds to the age and sex distribution of the adult Belgian population figures. The large difference in the regional distribution is due to the oversampling of the Brussels Capital Region in the BHIS.

Bivariate associations evaluating the characteristics with TL, mtDNAc, the lifestyle score or psychological distress as a parameter of mental health are presented in Additional file 1 : Table S4. Briefly, men had a − 6.41% (95% CI: − 9.10 to − 3.65%, p < 0.0001) shorter TL, a − 8.03% (95% CI: − 11.00 to − 4.96%, p < 0.0001) lower mtDNAc, lower odds of psychological distress (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.53 to 0.66, p < 0.0001) and a lifestyle score of − 0.28 (95% CI: − 0.32 to − 0.24, p < 0.0001) points less compared with women. Furthermore, a 1-year increment in age was associated with a − 0.64% (− 0.73 to − 0.55%, p < 0.0001) shorter TL and a − 0.19% (95% CI: − 0.31 to − 0.08%, p = 0.00074) lower mtDNAc.

Mental health prevalence and lifestyle characteristics

Within the BHIS subset, 32.3% and 18.0% of the participants had respectively psychological and severe psychological distress. 86.7% had suboptimal vitality, 12.0% indicated low life satisfaction and 22.0% had very bad to fair self-perceived health. The prevalence of depressive and generalised anxiety disorders was respectively 9.0% and 10.8%, respectively. 4.4% of the participants indicated to have had suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months. Similar results were found for the BELHES subset (Table 3 ).

Within the BHIS subset, the average lifestyle score (SD) was 3.1 (0.9) (Table 4 ). A histogram of the lifestyle score is shown in Additional file 1 : Fig. S2. 16.6% were regular smokers, and 4.9% reported 22 alcoholic drinks per week or more. 29.7% reported that their main leisure time included mainly sedentary activities, and 18.6% were underweight or obese. 29.2% were classified as having an unhealthy diet score. The participants of the BELHES subset were slightly more active, but no other dissimilarities were found (Table 4 ). The ROC curve shows an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.74, indicating a 74% predictive accuracy for the lifestyle score as a self-perceived health predictor (Additional file 1 : Fig. S3).

Healthy lifestyle and mental health and well-being

Living a healthier lifestyle, indicated by having a higher lifestyle score, was associated with lower odds of all mental health and well-being outcomes (Table 5 ). After adjustment, a one-point increment in the lifestyle score was associated with lower odds of psychological (OR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.69, 0.79) and severe psychological distress (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.64, 0.75). Similarly, for the same increment, the odds of suboptimal vitality, low life satisfaction and very bad to fair self-perceived health were respectively 0.62 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.68), 0.62 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.68) and 0.56 (95% CI: 0.52, 0.61). Finally, the odds of having depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder or suicidal ideation were respectively 0.57 (95% CI: 0.51, 0.63), 0.63 (95% CI: 0.57, 0.69) and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.72) for a one-point increment in the lifestyle score.

The biomarkers of ageing

After adjustment, living a healthy lifestyle was positively associated with both TL and mtDNAc (Table 6 ). A one-point increment in the lifestyle score was associated with a 1.74 (95% CI: 0.11, 3.40%, p = 0.037) higher TL and a 4.07 (95% CI: 2.01, 6.17%, p = 0.00012) higher mtDNAc.

People suffering from severe psychological distress had a − 4.62% (95% CI: − 8.85, − 0.20%, p = 0.041) lower mtDNAc compared with those who did not suffer from severe psychological distress. Similarly, people with suicidal ideation had a − 7.83% (95% CI: − 14.77, − 0.34%, p = 0.041) lower mtDNAc compared with those without suicidal ideation. No associations were found for the other mental health and well-being outcomes, and no associations were found between mental health and TL (Table 6 ).

Sensitivity analysis

Additional adjustment of the main analyses for perceived quality of social support, chronic disease or lifestyle score (in the association between the mental health outcomes and the biomarkers of ageing) did not strongly change the effect of our observations (Additional file 1 : Tables S5-S7). However, we noticed that most of the associations between severe psychological distress or suicidal ideation and mtDNAc showed marginally significant results.

In this study, we evaluated the associations between eight mental health and well-being outcomes, a healthy lifestyle score and 2 biomarkers of biological ageing: telomere length and mitochondrial DNA content. Having a healthy lifestyle was positively associated with all mental health and well-being indicators and the markers of biological ageing. Furthermore, having had suicidal ideation or suffering from severe psychological distress was associated with a lower mtDNAc. However, no association was found between mental health and TL.

In the first part of this research, we evaluated the association between lifestyle and mental health and well-being and showed that living a healthy lifestyle was positively associated with better mental health and well-being outcomes. Similar trends were found in previous studies for each of the health behaviours separately [ 11 , 12 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. Although evaluating these health behaviours separately provides valuable information, assessing them in combination with each other rather than independently might better reflect the real-life situation as they often co-occur and may exert a synergistic effect on each other [ 24 , 25 , 49 ]. For example, 68% of the adults in England engaged in two or more unhealthy behaviours [ 25 ]. Especially, smoking status and alcohol consumption co-occurred, but half of the studies in the review by Noble et al. indicated clustering of all included health behaviours [ 24 ].

To date, the number of studies evaluating the combination of multiple health behaviours and mental health and well-being in adults is limited, and most of them use a different methodology to assess this association [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ]. Firstly, differences are found between the included health behaviours. Most studies included the four “SNAP” risk factors, i.e. smoking, poor nutrition, excess alcohol consumption and physical inactivity. Other health behaviours that were sometimes included were BMI/obesity, sleep duration/quality and psychological distress [ 50 , 53 , 54 , 56 ]. Secondly, differences are found in the scoring of the health behaviours and the use of the lifestyle score. Whereas in this study the health behaviours were scored categorically, studies often dichotomised the health behaviours and/or the final lifestyle score [ 50 , 52 , 53 , 56 ]. Also, two studies performed clustering [ 54 , 55 ]. Health behaviours can cluster together at both ends of the risk spectrum, but less is known about the middle categories. This is avoided by using the cluster method where participants are clustered based on similar behaviours. On the other hand, a lifestyle score can be of better use and more easily be interpreted when aiming to compare healthy versus unhealthy lifestyles, as was the case for this study.

Despite these different methods, all previously mentioned studies show similar results. Together with our findings, which also support these results, this provides clear evidence that an unhealthy lifestyle is associated with poor mental health and well-being outcomes. Important to notice is that, like our research, most studies in this field have a cross-sectional design and are therefore not able to assume causality. Therefore, mental health might be the cause or the consequence of an unhealthy lifestyle. Further prospective and longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm the direction of the association.

Healthy lifestyle and biomarkers of ageing

How lifestyle affects our health is not yet fully understood. One possible pathway is through oxidative stress and biological ageing. An unhealthy lifestyle has been associated with an increase in oxidative stress [ 57 , 58 , 59 ], and in turn, higher concentrations of oxidative stress are known to negatively affect TL and mtDNAc [ 60 ]. In this study, we showed that living a healthy lifestyle was associated with a longer TL and a higher mtDNAc. Our results showed a stronger association of lifestyle with mtDNAc compared with TL. TL is strongly determined by TL at birth [ 61 ]. On the other hand, mtDNAc might be more variable in shorter time periods. Although mtDNAc and TL were strongly correlated, this could explain why lifestyle is more strongly associated with mtDNAc. However, we can only speculate about this, and further research is necessary to confirm our results.

Similar as for the association with mental health, in previous studies, the biomarkers have been associated with health behaviours separately rather than combined [ 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 ]. To our knowledge, we are the first to evaluate the associations between a healthy lifestyle score and mtDNAc. Our results are in line with our expectations. As TL and mtDNAc are known to be correlated [ 60 ], we would expect similar trends for both biomarkers. In the case of TL, few studies included a combined lifestyle score in association with this biomarker. Consistent with our results, in a study population of 1661 men, the sum score of a healthier lifestyle was correlated with a longer TL [ 66 ]. Similar results were found by Sun et al. where a combination of healthy lifestyles in a female study population was associated with a longer TL compared with the least healthy group [ 67 ]. Also, improvement in lifestyle has been associated with TL maintenance in the elderly at risk for dementia [ 68 ], and a lifestyle intervention programme was positively associated with leucocyte telomere length in children and adolescents [ 69 ]. These results suggest that on a biological level, a healthy lifestyle is associated with healthy ageing. Within this context, a study on adults aged 60 and older showed that maintaining a normal weight, not smoking and performing regular physical activity were associated with slower development of disability and a reduction in mortality [ 70 ]. Similarly, midlife lifestyle factors like non-smoking, higher levels of physical activity, non-obesity and good social support have been associated with successful ageing, 22 years later [ 71 ].

Mental health and well-being and biomarkers of ageing

Finally, we evaluated the association between the biomarkers of ageing and the mental health and well-being outcomes. The hypothesis that biological ageing is associated with mental health has been supported by observations showing that chronically stressed or psychiatrically ill persons have a higher risk for age-related diseases like dementia, diabetes and hypertension [ 23 , 72 , 73 ]. Important to notice is that, like our research, the majority of studies on this topic have a cross-sectional design and therefore are unable to identify causality. Therefore, it is currently unknown whether psychological diseases accelerate biological ageing or whether biological ageing precedes the onset of these diseases [ 74 ].

Our results showed a lower mtDNAc for individuals with suicidal ideation or severe psychological distress but not for any of the other mental health outcomes. Evidence on the association between mtDNAc and mental health is inconsistent. Women above 60 years old with depression had a significantly lower mtDNAc compared with the control group [ 75 ]. Furthermore, individuals with a low mtDNAc had poorer outcomes in terms of self-rated health [ 76 ]. In contrast, Otsuka et al. showed a higher peripheral blood mtDNAc in suicide completers [ 77 ], and studies on major depressive syndrome [ 78 ] and self-rated health [ 79 ] showed the same trend. Finally, Vyas et al. showed no significant association between mtDNAc and depression status in mid-life and older adults [ 80 ]. These differences might be due to the differences in study population and methods. For example, the two studies indicating lower mtDNAc in association with poor mental health both had an elderly study population, and one study population consisted of psychiatrically ill patients. Next to that, differences were found in the type of samples, mtDNAc assays and questionnaires or diagnostics. The inconsistency of these studies and our results calls for further research on this association and for standardisation of methods within studies to enable clear comparisons.

As for TL, we did not find an association with any of the mental health and well-being outcomes. Previous studies in adults showed a lower TL in association with current but not remitted anxiety disorder [ 81 ], depressive [ 82 ] and major depressive disorder [ 73 , 83 ], childhood trauma [ 84 ] suicide [ 77 , 85 ], depressive symptoms in younger adults [ 86 ] and acculturative stress and postpartum depression in Latinx women [ 87 ]. Also, in a meta-analysis, psychiatric disorders overall were associated with a shorter leucocyte TL [ 88 ]. However, other studies failed to demonstrate an association between TL and mental health outcomes like major depressive disorder [ 89 ], late-life depression [ 90 ] and anxiety disorder [ 91 ]. Again, this could be due to a different method to assess the mental health outcomes, a different study design, uncontrolled confounding factors and the type of telomere assay. For example, a meta-analysis showed stronger associations with depression when using southern blot or FISH assay compared with qPCR to measure telomere length [ 92 ].

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of this study is the use of a validated lifestyle score that can easily be reproduced and used for other research on lifestyle. Secondly, we were able to use a large sample size for our analyses in the BHIS subset. Thirdly, by assessing multiple dimensions of mental health and well-being, we were able to give a comprehensive overview of the mental health status. To our knowledge, we are the first to evaluate the associations between a healthy lifestyle score and mtDNAc.

Our results should however be interpreted with consideration for some limitations. As mentioned before, the study has a cross-sectional design, and therefore, we cannot assume causality. Secondly, for the lifestyle score, we used self-reported data, which might not always represent the actual situation. For example, BMI values tend to be underestimated due to the overestimation of height and underestimation of weight [ 93 ], and also, smoking behaviour is often underestimated [ 94 ]. Also, equal weights were used for each of the health behaviours as no objective information was available on which weight should be given to a specific health behaviour. Thirdly, there is a distinct time lag between the completion of the BHIS questionnaire and the collection of the BELHES samples. The mean (SD) number of days is 52 (35). This is less than the period for suicidal ideation, assessed over the 12 previous months, but there might be a more limited overlap with the period for assessment of the other mental health variables, such as vitality and psychological distress, assessed over the last few weeks, and depressive and generalised anxiety disorders, assessed over the last 2 weeks. Fourthly, due to a non-response bias, the lowest socio-economic classes are less represented in our study population. This will not affect our dose–response associations but might affect the generalisability of our findings to the overall population. Finally, we do not have data on blood cell counts, which has been associated with mtDNAc [ 95 ].

In this large-scale study, we showed that living a healthy lifestyle was positively associated with mental health and well-being and, on a biological level, with a higher TL and mtDNAc, indicating healthy ageing. Furthermore, individuals with suicidal ideation or suffering from severe psychological distress had a lower mtDNAc. Our findings suggest that implementing strategies to incorporate healthy lifestyle changes in the public’s daily life could be beneficial for public health, and might offset the negative impact of environmental stressors. However, further studies are necessary to confirm our results and especially prospective and longitudinal studies are essential to determine causality of the associations.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for this study is available through a request to the Health Committee of the Data Protection Authority.

Abbreviations

Area under the curve

Body mass index

Confidence intervals

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire

General Health Questionnaire

Inter-run calibrator

- Mitochondrial DNA content

Patient Health Questionnaire

Relative operating characteristic curve

Short Form Health Survey

- Telomere length

World Health Organization. Healthy living: what is a healthy lifestyle? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1999.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Tackling NCDs: ‘best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2019.

World Health Organization. 2021 Physical Activity Factsheets for the European Union Member States in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021.

Eurostat. Database on health determinants 2021 [Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/health/data/database?node_code=hlth_det .

Whitman IR, Agarwal V, Nah G, Dukes JW, Vittinghoff E, Dewland TA, et al. Alcohol abuse and cardiac disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(1):13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.048 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Koliaki C, Liatis S, Kokkinos A. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: revisiting an old relationship. Metabolism. 2019;92:98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2018.10.011 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Freisling H, Viallon V, Lennon H, Bagnardi V, Ricci C, Butterworth AS, et al. Lifestyle factors and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a multinational cohort study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1474-7 .

Liu Y, Pleasants RA, Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Heidari K, Malarcher AM, et al. Smoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged ≥ 45 years with a smoking history. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1409. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S82259 .

Kirsch Micheletti J, Bláfoss R, Sundstrup E, Bay H, Pastre CM, Andersen LL. Association between lifestyle and musculoskeletal pain: cross-sectional study among 10,000 adults from the general working population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):609. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-3002-5 .

Bowe AK, Owens M, Codd MB, Lawlor BA, Glynn RW. Physical activity and mental health in an Irish population. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188(2):625–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1863-5 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Richardson S, McNeill A, Brose LS. Smoking and quitting behaviours by mental health conditions in Great Britain (1993–2014). Addict Behav. 2019;90:14–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.011 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Levy MZ, Allsopp RC, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. J Mol Biol. 1992;225(4):951–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(92)90096-3 .

Shaughnessy DT, McAllister K, Worth L, Haugen AC, Meyer JN, Domann FE, et al. Mitochondria, energetics, epigenetics, and cellular responses to stress. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(12):1271–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408418 .

Cui Y, Gao YT, Cai Q, Qu S, Cai H, Li HL, et al. Associations of leukocyte telomere length with body anthropometric indices and weight change in Chinese women. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2582–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20321 .

Crous-Bou M, Fung TT, Prescott J, Julin B, Du M, Sun Q, et al. Mediterranean diet and telomere length in Nurses’ Health Study: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6674. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6674 .

Janssen BG, Gyselaers W, Byun H-M, Roels HA, Cuypers A, Baccarelli AA, et al. Placental mitochondrial DNA and CYP1A1 gene methylation as molecular signatures for tobacco smoke exposure in pregnant women and the relevance for birth weight. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-1113-4 .

Navarro-Mateu F, Husky M, Cayuela-Fuentes P, Álvarez FJ, Roca-Vega A, Rubio-Aparicio M, et al. The association of telomere length with substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Addiction. 2020;116(8):1954–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15312 .

Pyle A, Anugrha H, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Yarnall A, Burn D, Hudson G. Reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number is a biomarker of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;38:216.e7-.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.033 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ashar FN, Zhang Y, Longchamps RJ, Lane J, Moes A, Grove ML, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA copy number with cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(11):1247–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3683 .

Chen S, Lin J, Matsuguchi T, Blackburn E, Yeh F, Best LG, et al. Short leukocyte telomere length predicts incidence and progression of carotid atherosclerosis in American Indians: the Strong Heart Family Study. Aging. 2014;6(5):414–27. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100671 .

Mons U, Müezzinler A, Schöttker B, Dieffenbach AK, Butterbach K, Schick M, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality: results from individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 2 large prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(12):1317–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww210 .

Lindqvist D, Epel ES, Mellon SH, Penninx BW, Révész D, Verhoeven JE, et al. Psychiatric disorders and leukocyte telomere length: underlying mechanisms linking mental illness with cellular aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:333–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.007 .

Noble N, Paul C, Turon H, Oldmeadow C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the clustering of Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical activity (‘SNAP’) health risk factors. Prev Med. 2015;81:16–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.003 .

Poortinga W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med. 2007;44(2):124–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.006 .

Demarest S, Van der Heyden J, Charafeddine R, Drieskens S, Gisle L, Tafforeau J. Methodological basics and evolution of the Belgian Health Interview Survey 1997–2008. Arch Public Health. 2013;71(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-71-24 .

Goldberg DP. User’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 .

Cantril H. Pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 .

Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093 .

Gisle L, Drieskens S, Demarest S, Van der Heyden J. Enquête de santé 2018: Santé mentale. Bruxelles: Sciensano; 2018. ( https://www.enquetesante.be . Available from. Numéro de rapport: D/2020/14.440/3).

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Article Google Scholar

Braunholtz S, Davidson S, Myant K, O’Connor R. Well? What do you think?: the Third National Scottish Survey of Public Attitudes to Mental Health, Mental Wellbeing and Mental Health Problems. Scotland: Scottish Government Edinburgh; 2007.

Van Lente E, Barry MM, Molcho M, Morgan K, Watson D, Harrington J, et al. Measuring population mental health and social well-being. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(2):421–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0317-x .

de Bruin A, Picavet HSJ, Nossikov A. Health interview surveys: towards international harmonization of methods and instruments. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 1996.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Superior Health Council. Dietary guidelines for the Belgian adult population. Report 9284. Brussels: Superior Health Council; 2019.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

World Health Organization. HEARTS Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: healthy-lifestyle counselling. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

World Health Organization. Country profiles on nutrition, physical activity and obesity in the 28 European Union Member States of the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013.

Bhaskaran K, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(12):944–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30288-2 .

Benetou V, Kanellopoulou A, Kanavou E, Fotiou A, Stavrou M, Richardson C, et al. Diet-related behaviors and diet quality among school-aged adolescents living in Greece. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123804 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Martens DS, Plusquin M, Gyselaers W, De Vivo I, Nawrot TS. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and newborn telomere length. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0689-0 .

Janssen BG, Munters E, Pieters N, Smeets K, Cox B, Cuypers A, et al. Placental mitochondrial DNA content and particulate air pollution during in utero life. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(9):1346–52. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104458 .

Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med. 2017;15(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y .

Pavkovic B, Zaric M, Markovic M, Klacar M, Huljic A, Caricic A. Double screening for dual disorder, alcoholism and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:483–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.013 .

De Wit LM, Van Straten A, Van Herten M, Penninx BW, Cuijpers P. Depression and body mass index, a u-shaped association. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-14 .

Meader N, King K, Moe-Byrne T, Wright K, Graham H, Petticrew M, et al. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:657. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3373-6 .

Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A, Reza Roohafza H, Afshar H, Feizi A, et al. Combined healthy lifestyle is inversely associated with psychological disorders among adults. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0146888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146888 .

Bonnet F, Irving K, Terra J-L, Nony P, Berthezène F, Moulin P. Anxiety and depression are associated with unhealthy lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178(2):339–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.035 .

Loprinzi PD, Mahoney S. Concurrent occurrence of multiple positive lifestyle behaviors and depression among adults in the United States. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:126–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.073 .

Yang H, Gao J, Wang T, Yang L, Liu Y, Shen Y, et al. Association between adverse mental health and an unhealthy lifestyle in rural-to-urban migrant workers in Shanghai. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116(2):90–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2016.03.004 .

Oftedal S, Kolt GS, Holliday EG, Stamatakis E, Vandelanotte C, Brown WJ, et al. Associations of health-behavior patterns, mental health and self-rated health. Prev Med. 2019;118:295–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.017 .

Conry MC, Morgan K, Curry P, McGee H, Harrington J, Ward M, et al. The clustering of health behaviours in Ireland and their relationship with mental health, self-rated health and quality of life. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):692. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-692 .

Buttery AK, Mensink GB, Busch MA. Healthy behaviours and mental health: findings from the German Health Update (GEDA). The European Journal of Public Health. 2015;25(2):219–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku094 .

Ahmed NJ, Husen AZ, Khoshnaw N, Getta HA, Hussein ZS, Yassin AK, et al. The effects of smoking on IgE, oxidative stress and haemoglobin concentration. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(4):1069–72. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.4.1069 .

Langley MR, Yoon H, Kim HN, Choi C-I, Simon W, Kleppe L, et al. High fat diet consumption results in mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and oligodendrocyte loss in the central nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(3):165630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.165630 .

Tan HK, Yates E, Lilly K, Dhanda AD. Oxidative stress in alcohol-related liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2020;12(7):332–49. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i7.332 .

Martens DS, Nawrot TS. Air pollution stress and the aging phenotype: the telomere connection. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2016;3(3):258–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-016-0098-8 .

Martens DS, Van Der Stukken C, Derom C, Thiery E, Bijnens EM, Nawrot TS. Newborn telomere length predicts later life telomere length: tracking telomere length from birth to child- and adulthood. EBioMedicine. 2021;63:103164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103164 .

Hang D, Nan H, Kværner AS, De Vivo I, Chan AT, Hu Z, et al. Longitudinal associations of lifetime adiposity with leukocyte telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(5):485–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0382-z .

Gu Y, Honig LS, Schupf N, Lee JH, Luchsinger JA, Stern Y, et al. Mediterranean diet and leukocyte telomere length in a multi-ethnic elderly population. Age. 2015;37(2):24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-015-9758-0 .

Sellami M, Al-Muraikhy S, Al-Jaber H, Al-Amri H, Al-Mansoori L, Mazloum NA, et al. Age and sport intensity-dependent changes in cytokines and telomere length in elite athletes. Antioxidants. 2021;10(7):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10071035 .

Savela S, Saijonmaa O, Strandberg TE, Koistinen P, Strandberg AY, Tilvis RS, et al. Physical activity in midlife and telomere length measured in old age. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(1):81–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.02.003 .

Mirabello L, Huang WY, Wong JY, Chatterjee N, Reding D, David Crawford E, et al. The association between leukocyte telomere length and cigarette smoking, dietary and physical variables, and risk of prostate cancer. Aging Cell. 2009;8(4):405–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00485.x .

Sun Q, Shi L, Prescott J, Chiuve SE, Hu FB, De Vivo I, et al. Healthy lifestyle and leukocyte telomere length in US women. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e38374. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038374 .

Sindi S, Solomon A, Kåreholt I, Hovatta I, Antikainen R, Hänninen T, et al. Telomere length change in a multidomain lifestyle intervention to prevent cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. J Gerontol A. 2021;76(3):491–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa279 .

Paltoglou G, Raftopoulou C, Nicolaides NC, Genitsaridi SM, Karampatsou SI, Papadopoulou M, et al. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary, personalized, lifestyle intervention program is associated with increased leukocyte telomere length in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082682 .

Chakravarty EF, Hubert HB, Krishnan E, Bruce BB, Lingala VB, Fries JF. Lifestyle risk factors predict disability and death in healthy aging adults. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):190–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.006 .

Bosnes I, Nordahl HM, Stordal E, Bosnes O, Myklebust TÅ, Almkvist O. Lifestyle predictors of successful aging: a 20-year prospective HUNT study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0219200. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219200 .

Epel ES, Prather AA. Stress, telomeres, and psychopathology: toward a deeper understanding of a triad of early aging. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:371–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045054 .

Verhoeven JE, Révész D, Epel ES, Lin J, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and accelerated cellular aging: results from a large psychiatric cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(8):895–901. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.151 .

Han LK, Verhoeven JE, Tyrka AR, Penninx BW, Wolkowitz OM, Månsson KN, et al. Accelerating research on biological aging and mental health: current challenges and future directions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;106:293–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.04.004 .

Kim MY, Lee JW, Kang HC, Kim E, Lee DC. Leukocyte mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content is associated with depression in old women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53(2):e218–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2010.11.019 .

Mengel-From J, Thinggaard M, Dalgard C, Kyvik KO, Christensen K, Christiansen L. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood cells declines with age and is associated with general health among elderly. Hum Genet. 2014;133(9):1149–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-014-1458-9 .

Otsuka I, Izumi T, Boku S, Kimura A, Zhang Y, Mouri K, et al. Aberrant telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in suicide completers. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3176.

Chung JK, Lee SY, Park M, Joo E-J, Kim SA. Investigation of mitochondrial DNA copy number in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;282:112616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112616 .

Takahashi PY, Jenkins GD, Welkie BP, McDonnell SK, Evans JM, Cerhan JR, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA copy number with self-rated health status. Appl Clin Genet. 2018;11:121–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S167640 .

Vyas CM, Ogata S, Reynolds CF 3rd, Mischoulon D, Chang G, Cook NR, et al. Lifestyle and behavioral factors and mitochondrial DNA copy number in a diverse cohort of mid-life and older adults. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237235. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237235 .

Verhoeven JE, Révész D, van Oppen P, Epel ES, Wolkowitz OM, Penninx BW. Anxiety disorders and accelerated cellular ageing. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(5):371–8. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.151027 .

Pisanu C, Vitali E, Meloni A, Congiu D, Severino G, Ardau R, et al. Investigating the role of leukocyte telomere length in treatment-resistant depression and in response to electroconvulsive therapy. J Pers Med. 2021;11(11):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111100 .

da Silva RS, de Moraes LS, da Rocha CAM, Ferreira-Fernandes H, Yoshioka FKN, Rey JA, et al. Telomere length and telomerase activity of leukocytes as biomarkers of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor responses in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2022;32(1):34–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ypg.0000000000000305 .

Aas M, Elvsåshagen T, Westlye LT, Kaufmann T, Athanasiu L, Djurovic S, et al. Telomere length is associated with childhood trauma in patients with severe mental disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0432-7 .

Birkenæs V, Elvsåshagen T, Westlye LT, Høegh MC, Haram M, Werner MCF, et al. Telomeres are shorter and associated with number of suicide attempts in affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:1032–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.135 .

Phillips AC, Robertson T, Carroll D, Der G, Shiels PG, McGlynn L, et al. Do symptoms of depression predict telomere length? Evidence from the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(3):288–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318289e6b5 .

Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Polcari JJ, Nephew BC, Harris R, Zhang C, Murgatroyd C, et al. Acculturative stress, telomere length, and postpartum depression in Latinx mothers. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;147:301–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.063 .

Darrow SM, Verhoeven JE, Révész D, Lindqvist D, Penninx BW, Delucchi KL, et al. The association between psychiatric disorders and telomere length: a meta-analysis involving 14,827 persons. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(7):776–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000356 .

Simon NM, Walton ZE, Bui E, Prescott J, Hoge E, Keshaviah A, et al. Telomere length and telomerase in a well-characterized sample of individuals with major depressive disorder compared to controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.004 .

Schaakxs R, Verhoeven JE, Voshaar RCO, Comijs HC, Penninx BW. Leukocyte telomere length and late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(4):423–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.06.003 .

de Baumont AC, Hoffmann MS, Bortoluzzi A, Fries GR, Lavandoski P, Grun LK, et al. Telomere length and epigenetic age acceleration in adolescents with anxiety disorders. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7716. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87045-w .

Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The association between depression and leukocyte telomere length: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(4):229–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22351 .

Drieskens S, Demarest S, Bel S, De Ridder K, Tafforeau J. Correction of self-reported BMI based on objective measurements: a Belgian experience. Archives of Public Health. 2018;76:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0255-7 .

Gorber SC, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, Levasseur G, Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):12–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntn010 .

Knez J, Winckelmans E, Plusquin M, Thijs L, Cauwenberghs N, Gu Y, et al. Correlates of peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA content in a general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(2):138–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv175 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all BHIS and BELHES participants for contributing to this study.

The HuBiHIS project is financed by Sciensano (PJ) N°: 1179–101. Dries Martens is a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO 12X9620N).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sciensano, Risk and Health Impact Assessment, Juliette Wytsmanstraat 14, 1050, Brussels, Belgium

Pauline Hautekiet, Nelly D. Saenen & Eva M. De Clercq

Centre for Environmental Sciences, Hasselt University, 3500, Hasselt, Belgium

Pauline Hautekiet, Nelly D. Saenen, Dries S. Martens, Margot Debay & Tim S. Nawrot

Sciensano, Epidemiology and Public Health, Juliette Wytsmanstraat 14, 1050, Brussels, Belgium

Johan Van der Heyden