Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Topics and destinations in comments on YouTube tourism videos during the Covid-19 pandemic

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Facultad de Economía y Empresa, Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Universidad Espíritu Santo, Samborondón, Ecuador

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanísticas, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, ESPOL, Guayaquil, Ecuador

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Orly Carvache-Franco,

- Mauricio Carvache-Franco,

- Wilmer Carvache-Franco,

- Olga Martin-Moreno

- Published: March 2, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100

- Reader Comments

This study examines the comments posted on tourism-related YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic to establish sustainable development strategies in destinations. Its objectives were: (i) to identify the topics of discussion, (ii) to establish the perceptions of tourism in a pandemic crisis, and (iii) to identify the destinations mentioned. The data was collected between January and May 2020. 39,225 comments were extracted in different languages and globally through the YouTube API. The data processing was carried out using the word association technique. The results show that the most discussed topics were: “people,” “country,” “tourist,” “place,” “tourism,” “see,” “visit,” “travel,” “covid-19,” “life,” and “live,” which are the focus of the comments made on the perceptions found and represent the attraction factors shown by the videos and the emotions perceived in the comments. The findings show that users’ perceptions are related to risks since the “Covid-19” pandemic is associated with the impact on tourism, people, destinations, and affected countries. The destinations in the comments were: India, Nepal, China, Kerala, France, Thailand, and Europe. The research has theoretical implications concerning tourists’ perceptions of destinations since new perceptions associated with destinations during the pandemic are shown. Such concerns involve tourist safety and work at the destinations. This research has practical implications since, during the pandemic, companies can develop prevention plans. Also, governments could implement sustainable development plans that contain measures so that tourists can make their trips during a pandemic.

Citation: Carvache-Franco O, Carvache-Franco M, Carvache-Franco W, Martin-Moreno O (2023) Topics and destinations in comments on YouTube tourism videos during the Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0281100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100

Editor: Tauseef Ahmad, King Saud University, SAUDI ARABIA

Received: March 12, 2022; Accepted: January 15, 2023; Published: March 2, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Carvache-Franco et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data were collected through the YouTube API using Mozdeh big data text analysis software ( http://mozdeh.wlv.ac.uk/ ). The book "Social Web Text Analytics with Mozdeh" ( http://mozdeh.wlv.ac.uk/resources/SocialWebResearchWithMozdeh.pdf ), the Youtube Data API v3 key ( https://developers.google.com/youtube/v3/docs and http://lexiurl.wlv.ac.uk/searcher/YouTubeKeyRegister.html ), and the video "Social Media Data Analysis 5: Gathering and analysing YouTube comments with Mozdeh" by Mike Thelwall ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvpJQXvI-XA ) contain the full information on how to extract and analyze YouTube data with the software. The keyword used for queries in data collection was "tourism" in the title of the video or in the description of the video (videos with titles or descriptions matching queries). The comments of the YouTube videos were obtained from January to May 2020.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

A growing number of studies have been focusing on tourism crises and change in recent years. Yet only a few have explicitly investigated health-related crises [ 1 – 4 ]. In 2020, the COVID-19 virus, has triggered an unprecedented global crisis with enormous impacts on our political, social, and economic systems [ 5 , 6 ].

The Chinese government first reported this virus to WHO on December 31, 2019. WHO declared the pandemic on March 11, 2020 [ 7 ].On March 26, 2020, UNWTO [ 8 ] announced that the United Nations Specialized Tourism Agency expected international tourist arrivals to decrease by 20% and 30% in 2020 compared to 2019 figures, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 7, 2020, UNWTO [ 9 ] announced that international tourism decreased by 22% in the first quarter and could fall by as much as 60%-80% throughout the year. The Covid-19 crisis currently presents the opportunity to reconsider sustainable tourism transformation on a global level [ 10 ]. For Yu et al. [ 11 ], future studies should examine how the crisis affect the quality and efficiency of tourism companies’ services: performance and image of the destination and mediation of tourist emotions expressed in social networks during a health crisis.

The tourism activity produces a large amount of data, which can be addressed through social networks [ 12 ]. In this way, with the development of information and communications technology, people can share their opinions online, creating user-generated content [ 13 ]. These comments from social networks can serve as sources to know tourists’ perceptions and impressions [ 14 ]. Nationality and culture are critical elements for tourists’ preferences, and with the processing of tourists’ comments on social networks, the preferences of various nationalities and cultures can be understood [ 15 ].

In this context, the present study sets the following objectives: (i) to establish the issues that are discussed in user comments on YouTube videos related to tourism during the Covid-19 pandemic, (ii) to establish the perceptions of tourism in a pandemic crisis, and (iii) to establish the destinations mentioned in the comments on the YouTube videos related to tourism during the Covid-19 pandemic.

2. Literature review

2.1. tourism in pandemic crisis.

The tourism industry is vulnerable to risks, including pandemics, epidemics, crisis, terrorism, or any risk threatening tourist safety [ 16 , 17 ]. Pandemics and travel relationships are fundamental to understanding health, security, and global change [ 18 ]. Consequently, crises can be a trigger for change, but no crisis has so far been a significant transition event in tourism [ 19 ].

The 21st century has already experienced four pandemics: SARS in 2002. Avian influenza in 2009, MERS in 2012, and Ebola, which peaked in 2013–14. Risk often restricts travel and has a negative relationship with tourism demand. For example, SARS and the bird flu in Asia [ 20 , 21 ], swine flu [ 22 ], Ebola [ 23 ] and MERS [ 24 ].

Few reasearchers have studied the crisis of tourism during a pandemic. Yu et al. [ 11 ], concerning Covid-2019, established that the key issues identified and discussed in social networks including the perception of tourists risk, which changes dynamically, the effects of the quality of the service of tourism companies during a crisis, quarantine issues in public health, the authenticity of media coverage, and racial discrimination. Similarly, for Nguyen and Coca-Stefaniak [ 25 ], there are significant changes in planned travel behaviors after the Covid-2019 pandemic. More specifically, there is a decrease in the intentions to use public transportation and an increased willingness to using private cars. Therefore, the adverse effects of Covid-2019 on tourism can exacerbate income imbalances and harm social equity. As time passes without a vaccine, the adverse effects will intensify, and this can cause a significant delay in economic recovery [ 26 ].

Studies on the perception of risk in tourism during a pandemic have been carried out on the tourist or demand side and the resident side of tourist sites or supply [ 27 ]. On the risk of a pandemic by tourists or demand, existing studies focus on consumer behavior and mention that tourists perceive risks differently. This risk is associated with some factors such as health and safety. These risks make tourists change their preference for destinations that they believe have a lower level of health and safety risk [ 28 ]. On the demand side, some studies have focused on managing tourism crises that affect destinations, response and recovery strategies, and planning practices [ 29 ].

2.2. YouTube on social media and in tourism

YouTube videos have emerged as a source for research [ 30 ]. Social media can facilitate responses from multiple voices from organizations and consumers [ 31 , 32 ]. Understanding online dialogues helps understand communication during crises [ 33 ]. YouTube is a video-based social network. The main reason for watching videos is that it is relaxing entertainment. At the same time, interacting with others leads them to comment on said videos [ 34 ]. The comments posted on YouTube videos are interesting and provide information on the public’s reaction to the videos [ 35 ]. In this sense, videos with informative content have high validity when large samples are extracted from different regions [ 36 ].

YouTube is a website for broad content distribution and viral content sharing [ 37 ]. It is possible to find patterns in the themes and differences of gender and feelings while analyzing YouTube comments [ 38 ]. The comments on YouTube allow us to know the users’ emotional states [ 39 ]. Approximately 60 to 80% of the comments on YouTube from users may contain opinions, which is why it is an important source for obtaining user opinions, which can affect an organization’s reputation [ 40 ].

Various studies have used YouTube as a means of researching social media: analysis of user comments on science YouTube channels [ 41 ]; analysis of user comments on museums to establish gender differences [ 35 ]; analysis of video comments on anti-tourist incidents [ 42 ]; analysis of patterns and trends in YouTube video viewing [ 43 ]; and analysis of user behavior associated with the comments made on YouTube [ 44 ]. Few studies have raised the influence of social media in disasters and pandemics [ 45 ], and social media is considered as an important way of expressing oneself after pandemic disasters [ 46 ].

YouTube videos about tourist destinations have been used as a tool to communicate identity and brand. YouTube videos about tourist destinations are promotional and commercial videos, generally of an informative nature that communicate the destination’s brand through attraction factors and emotional values [ 47 ].

The offer of tourist destinations is of an intangible nature and due to the fact that they cannot be tested before their acquisition, service providers can take advantage of technology and its advances so that marketing managers in this area can give to know their services through audiovisual content, the purpose of audiovisual advertising material is to help destinations create a positive image, improve perceptions and attitudes, as well as influence visiting behavior, that is, in the visit attempt, in the return, sharing, recommending destinations, among other aspects [ 48 ].

Specifically, YouTube allows you to measure DCE (Digital consumer engagement), which consists of the level of interaction that a brand can have in a digital environment, through "clicks" on a video, "likes" "dislikes", comments and the fact of sharing the content. Writing a comment requires attention, time, involvement and cognitive resources of the users, so this gives a high indicator of the DCE mentioned above [ 49 ].

Given the success of the YouTube platform, companies have found that creating their own channels is an excellent way to achieve a high level of DCE, reach new audiences and convert visits into sales. YouTube makes it possible to characterize how users react to videos, which allows for a quantitative analysis (through the number of likes, clicks, etc.), as well as a qualitative analysis (analysis of the detailed information in the comments) [ 50 ].

2.3. Crisis communication theory

The crisis communication theories that have been applied to tourism are: (a) Situational crisis communication theory [ 51 , 52 ] and Networked crisis communication theory [ 53 , 54 ]. The latter is used for communication in social media using media such as Facebook or YouTube. The literature on communication in crisis in health-related tourism is still scarce [ 55 , 56 ].

The theory of situational crisis communication suggests that organizations can use various communication strategies during crises. These strategies depend on the type of crisis, the situation of the crisis, and the organization’s responsibility in the crisis [ 57 ]. The theory of situational crisis communication tries to establish strategies of responses to crises with positive results for the organization in the public perception of the crisis and its attitude to protecting its reputation and reducing those adverse effects [ 51 , 52 ].

During crises, response strategies represent the words or terms and the actions that organizations can take during the crisis [ 51 ]. In crises when there is a minimum responsibility of the organization, the appropriate communication strategies are instructions and information adjustment, to achieve positive results for organizations such as protecting their reputation and reducing negative effects [ 57 , 58 ].

The theory of situational crisis communication in tourism was tested in social media. Barbe and Pennington-Gray [ 54 ] used Twitter. While Möller et al. [ 55 ] and Ki and Nekmat [ 58 ] used Facebook. Sandlin and Gracyalny [ 59 ] used YouTube to examine comments on public figures.

The theory of situational crisis communication, like the classical theories of crisis communication, focuses on the interaction of the type of crisis and the communication strategy. It does not consider the importance of the medium used in crisis communication in social media that could have a more significant effect than the effects of the type of crisis [ 57 ]. In this sense, for Schultz et al. [ 53 ], the consumer has different media types in social media in the context of different responses to the crises.

The Networked crisis communication theory considers that crisis communications distributed by social media can provoke different responses, which are affected or impacted by the medium used, the type of crisis, and also by people’s emotions [ 53 , 54 ]. Therefore, there is a gap in the literature on the effect of crisis communication in social networks from the recipient’s perspective, since social networks can facilitate responses from multiple voices of organizations and the public or consumers [ 31 ].

In summary, the literature indicates that tourists associate health risks during pandemics with the quality of service and safety, which makes them change their preferences for destinations with a lower level of risk. However, little literature addresses the perceptions and reactions in user comments about tourism videos on YouTube at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic concerning whether these perceptions denote risks and show preferences in certain destinations. Therefore, in light of this research gap, this study asks the following research questions:

- RQ1. Which topics are discussed in comments in tourism YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic?

- RQ2. What perceptions do users have about the tourism crisis during the Covid-19 Pandemic?

- RQ3. Which destinations are discussed in comments in tourism YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic?

3. Methodology

3.1. techniques for data analysis.

In recent years, modern techniques have emerged from analyzing social media’s big data, such as association mining or word associations and the technique of analysis of sentiment of comments. This research uses the technique of word associations or association of word content for comments on YouTube videos.

3.1.1 Association mining or word associations

The association technique is used to find syntagmatic relationships between terms or words [ 60 ]. It is a technique to find patterns in texts processed in large volumes [ 61 ]. It is also a technique used to find the knowledge derived from the extraction of previously unknown patterns [ 62 ], and it is a quantitative technique to relate words [ 63 ]. When it has large volumes of data, this technique is used to classify and explain using existing knowledge or test hypotheses or interrelations between constructs [ 64 ].

Through the analysis of tourism data in the network, connections between textual data terms are found [ 65 ]. The word associations generally uses a quantitative approach to analyze more extensive text volumes. It helps discover knowledge by increasing the text’s volume to be analyzed [ 66 ].

Association mining or word association has been used in tourism to process volumes of online comments from restaurant customers [ 67 ], as well as to process online opinions of travelers [ 68 ], to process online comments of tourism products [ 69 ], to process online comments of restaurants, hotels and attractions [ 70 ], to process online comments of the image of a tourist destination [ 71 ], to process online comments that serve to analyze the behavior of tourists to market tourist destinations [ 72 ], to process comments online on hotel satisfaction factors [ 73 ], to compare various online platforms on hotel population comments [ 74 ], to process comments online restaurants [ 75 ], to process online comments of customer satisfaction in hotels [ 76 ], and to predict tourist demand [ 77 ].

Language is the most reliable and common way for humans to make their inner thoughts known in a way that other people can understand [ 49 ]. Texts are the direct expressions of users’ needs and emotions, so text-based analysis in the tourism sector has the potential to transform the industry, since decision-making is undoubtedly directly influenced by the experiences of trips of other tourists, made in comments on social networks or through blogs [ 80 ]. These texts can provide valuable insights for potential tourists and assist them in optimally choosing a destination, as well as exploring travel routes, or they can also help entrepreneurs in the tourism sector to improve their value proposition [ 78 ].

In general, "word association" techniques have been used to propose and perform tourism analysis to develop tourism value analysis models, build tourism recommendation systems, create tourism profiles and create policies to supervise tourism markets [ 78 ]. The advanced analysis of information provided by customers is a way to acquire, maintain, engage and satisfy their needs in an optimal way. It also allows creating transparency, segmentation of the population, replacement or support in the decision-making of individuals [ 79 ]. This is the importance of carrying out data analysis, since through comprehensive evaluation indicators, the analysis can be used to create an offer of personalized intelligent services for both tourists and tourism providers [ 80 ].

The analysis of social networks or social media analytics—SMA is considered as the structured and unstructured analysis of data obtained through social networks. Carrying out an SMA includes sentiment analysis and is useful to access and understand the behavior of users, or the group of users more broadly defined as society, especially in uncertain conditions such as the COVID-19 pandemic. An SMA generates new leads through customer experience and operational efficiency [ 79 ].

3.2. Data collection

The data was collected through the YouTube API using Mozdeh big data text analysis software. 158,578 comments were extracted in different languages from different countries. 39,225 comments corresponding to the Covid-19 pandemic, from January to May 2020, were obtained. These comments met the condition that the video included, in its title or the video description, the term “tourism”.

3.3. Data analysis

As part of the processing, the data analysis followed these steps:

First, data cleansing was performed checking and removing duplicate comments to improve the quality of the data to be analyzed.

Second, the word association technique was used to obtain the words associated with the term tourism in the YouTube data collected using Mozdeh big data text analysis software automatically check for associations between a query keywords extracting the words from all matching texts, and further analysing the statistically significant terms with a quantitative process with Pearson’s Chi-square statistical test, derived from a 2x2 contingency table used with a critical threshold value of 3,841. The Benjamini and Hochberg [ 81 ] method was used to reduce the risk of falsely believing that a word is significant when examining multiple Chi-square values. This procedure tests all the words simultaneously and shows all the words as results or meaningful terms. This method controls the risk of false positives when running multiple tests. Explanatory tables were prepared with the results.

Third, a dendrogram of clusters was developed to identify the most relevant terms or those that belong to each cluster. Fourth, for each discussion topic, the word association technique was used to obtain the five words associated with each discussion topic found in the collected YouTube data. Lastly, the videos’ comments were analyzed to identify the users’ perceptions related to the five words associated with each discussion topic.

4.1. Topics discussed in the comments of YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic

The data processing using the word association technique is shown in Table 1 . The most discussed topics in the YouTube comments were: “people,” “country,” “tourist,” “place,” “tourism,” "see,” "visit,” "travel,” "covid-19,” "life,” "live," and others, those topics reflect the main aspects on which users commented at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic. In Table 1 , the “Match” column displays the percentage of comments that contain the word that matches the term Covid-19. The “NoMatch” column displays the percentage of comments that contain the word that does not match the data collected with the search term Covid-19. The “Matches” column is the number of comments that match the word with the term Covid-19. The “Total” column is the number of comments that contain the word. The “DiffPZ” column is the difference in proportion z. The “Sig” column shows if the relationship was significant to the Chisq test performed.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100.t001

From the terms found in Table 1 , a dendrogram of clusters was obtained in SPSS software using data from matches column of Table 1 to determine the most hierarchical terms based on the frequency of comments for each term, shows that the terms people, country, tourism, tourist, place, see are the most significant in the hierarchy.

It is observed that in cluster 1, there are the terms “people,” “country,” “tourist,” "place," "tourism," and "see" identified as the group with the highest hierarchy ( Fig 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100.g001

The results show the topics that users had discussed most frequently in YouTube tourism videos. These topics reflect the main aspects on which users commented at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: the terms that are the focus of attention of the comments. The findings are shown in Table 1 . These results respond to RQ1: Which topics are discussed in comments in tourism YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic? The study found that the most commented topics are mainly: people, country, tourist, place, tourism, see, visit, travel, and others.

The results of YouTube users’ perceptions of the tourism crisis during the pandemic are shown in Table 2 show the perception of users about the situation of destinations, people, tourism, tourists during the pandemic. These respond to RQ2. What perceptions do users have about the tourism crisis during the Covid-2019 Pandemic? The findings show the perceptions grouped into three aspects:

- The perceptions and impressions of users of tourism videos on YouTube during the Covid-19 pandemic indicate that tourists relate destinations to countries, their people, and the things they can see in those destinations.

- The term "Covid-19" is associated with the effect or impact on tourism, people, destinations, and countries affected.

- The tourist perceives the need for work from the destination and the problems they could have in those places.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100.t002

4.2. Destinations discussed in the tourism YouTube videos

The most mentioned destinations in the comments of the YouTube users in the tourism videos are shown in Table 3 , these destinations focus on in the perception of users. The answer to the RQ3: Which destinations are discussed in comments in tourism YouTube videos during the Covid-19 pandemic? is given. The most commented destinations were: India, Nepal, China, Kerala, France, and Thailand.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281100.t003

5. Discussion

YouTube videos about tourist destinations are informative and communicate the destination brand through attraction factors and emotional values [ 47 ]. Comments on YouTube represent tourists’ perceptions and their impressions [ 15 ]. The main discussion topics found in the comments were: "people", "country", "tourist", "place", "tourism", "see", "visit", "travel", "covid-19", " life "," live ", which shows the themes that focus the perceptions and impressions of tourists about the videos and the emotions perceived in the comments.

These perceptions show that tourists relate the destinations with the countries, their people and the things they see in those destinations. Tourists perceive the need for work from the destination and the problems they could have in those places. The findings show that users’ perceptions are related to risks since the "covid-19" pandemic is associated with the impact on tourism, people, destinations, and affected countries. This result is related to other authors’ studies that have found tourists perceive risks in pandemics [ 11 , 28 , 29 ]. Also, with studies on tourism crises that affect destinations [ 30 ]. Besides, risk restricts travel and negatively affects tourism demand [ 11 , 21 – 25 ]. As a contribution, it is established that these responses incorporate preferences such as tourist safety and work from the destination, which the tourist has associated with the destinations related to the Covid-19 situation, which is concerning other studies that mention significant changes in tourist behavior during pandemics [ 29 ] and changes in planned travel behaviors after the covid-19 pandemic [ 26 ].

Other terms used were "information" and "guide" that indicate that consumers considered the videos in information and guides about destinations appropriate, and terms such as "hotel," "culture," "history" that showed characteristics of the destinations and "money" what they needed to stay in the destinations. Destinations mentioned in the comments that correspond to consumer perceptions and impressions include: India, Nepal, China, Kerala, France, Thailand and Europe, these destinations were promoted in the tourism videos that tourists focused their reaction on. on the comments.

YouTube videos comprise a type of communication from tourism providers to consumers [ 47 ]. However, during tourism crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, these videos available on YouTube, can be considered as a type of crisis communication from organizations to consumers. This crisis communication analyzed under the theory of situational crisis communication, in the case of crises with minimal responsibility of the organizations, corresponds to communicative strategies of adjustment of instructions and information [ 51 , 52 ] and these YouTube videos related to the tourism are considered informative videos and intended to preserve the reputation of the destination and companies. Analysis of the comments shows that there is a favorable consumer reaction to crisis communication from organizations and destinations related to the countries, their people and the things that can be seen in those destinations. The responses to said consumer crisis communication expressed through comments refer to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the tourist destination, producing an impact on the people, the problems and the work from that place. Tourism service companies using crisis communication strategies through YouTube can preserve the reputation of the destination and the companies.

The responses or crisis communication analyzed through the network crisis communication theory show that videos on YouTube that generally seek to promote tourist destinations can generate various responses driven by the emotions of consumers. Research findings indicate that such responses and reactions range from comments related to people, culture, history, country, the money needed, and the impact of Covid-19 on people and the destination. These being clear problems that can be found in a tourist destination. YouTube, as a medium or social networking, can influence the consumer’s response to the crisis.

As recommendations for the sustainability of destinations in times of health crisis due to the fact that tourists in tourist videos during the pandemic show concern for the people and places affected, it is necessary for governments to take measures in destinations such as: worry that people have work, serve communities in situations of health risk or poverty, worry about the safety of tourists, worry about changes in tourist behavior, collaborate with the planning of tourist trips, improve the stay of tourists in hotels, create tourist packages with biosecurity, and preserve the history and culture of the affected places. For this, all governments could contribute with sustainable plans for tourist trips because they are a source of income that, if properly managed in this sector of the economy, can contribute money and work to the affected areas in times of health crisis and times of pandemics.

6. Conclusions

The processing of user comments about tourism videos on YouTube through big data techniques, such as word association, is a suitable means to obtain the perceptions and impressions/reactions of users written in comments to the videos.

The perceptions and impressions of users of tourism videos on YouTube during the Covid-19 pandemic are mainly concentrated on the topics: "people," "country," "tourist," "place," "tourism," "see," evidencing that the tourist in the "Covid-19" pandemic perceives an effect or impact on tourism, people, destinations and affected countries. Interest is shown in the need for work from the destination and tourists’ problems in those places. Destinations mentioned in the comments include India, Nepal, China, Kerala, France, Thailand, and Europe.

This research has theoretical implications regarding the perceptions of tourists about destinations, since the data examined shows new perceptions that tourists have associated with destinations during the Covid-19 pandemic, such as tourist safety and work from destinations, this being the contribution to academic literature.

Comments on tourist videos, analyzed from the situational crisis communication theory [ 51 , 52 ], show that tourist service companies use crisis communication strategies through videos on YouTube to try to preserve the reputation of destinations. The companies and the comments to the tourist videos, analyzed from the theory of network crisis communication, show the ability of YouTube as a means to influence the response of tourists or consumers in the perception of risk and at the same time show the reactions driven by the emotions of tourists.

This study has practical implications since, during tourism crises caused by pandemics, companies can, through YouTube video, improve business crisis communication strategies and develop pandemic crisis prevention plans. To improve the sustainability of destinations, due to the concern that tourists show in the videos for the people and destinations affected, it is necessary for governments to develop sustainable plans aimed at tourists to generate employment and safety in planned trips so that they contribute to the sustainable development of the affected destinations by conducting responsible and sustainable tourism in times of health crises or pandemics.

Finally, the study’s main limitation is the temporality of the data collected during January and May 2020. As a future research line, it would be interesting to analyse the YouTube data to examine changes in consumer tourist behavior due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 8. UNWTO. International tourist arrivals could fall by 20–30% in 2020. From: https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-arrivals-could-fall-in-2020

- 9. UNWTO. The figures of international tourists could fall 60–80% in 2020,REPORT UNWTOI.2020. from https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-05/200507%20-%20Barometer%20ES.pdfu

- 13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101818

- PubMed/NCBI

- 52. Coombs WT. Ongoing crisis communication: planning, managing, and responding. Sage Publications; 2014.

- 60. Correia A, Teodoro MF, Lobo V. Statistical methods for word association in text mining. En: Contributions to Statistics. Cham: Springer Int Publish; 2018. p. 375–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.04.004

- 61. Vieira M, Portela F, Santos MF. Detecting automatic patterns of stroke through text mining. En: Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering. Cham: Springer Int Publish; 2019. p. 58–67.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

How do short videos influence users’ tourism intention a study of key factors.

- 1 School of Management, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing, China

- 2 School of Information Management, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Background: Short videos play a key role in the process of tourism destination promotion, and attractive short videos can bring tourist flow and economic income growth to tourist attractions. Many tourist attractions in China have achieved remarkable success through short video promotion.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to investigate the behavioral characteristics of short video users browsing short tourism videos and explore what factors of short video affected users’ tourism intention. This study also compared which factors were most important in triggering users’ tourism intention in marketing communication via short tourism videos in order to shed light on tourism destination strategy and facilitate adaptation to market development trends.

Methods: This study developed a conceptual model by extending the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model with technology acceptance factors (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use) and short video factors (perceived enjoyment, perceived professionalism, perceived interactivity) to examine users’ tourism intention. A convenience random sampling technique was used to distribute the questionnaire in Chinese city of Nanjing. Four hundred twenty-one respondents participated in the questionnaire, with 395 providing valid data.

Results: The results of the SEM analysis show that all posed hypotheses (Perceived professionalism - > Telepresence, Perceived interactivity - > Telepresence, Perceived enjoyment - > Telepresence, Perceived ease of use - > Telepresence, Perceived enjoyment - > Flow experience, Perceived ease of use - > Flow experience, Telepresence - > Flow experience, Telepresence - > Tourism intention, Flow experience - > Tourism intention) are confirmed except for (Perceived usefulness - > Tourism intention), which is not confirmed.

Conclusion: The findings of this study will help fill the gap in previous research on the relationship between short video influencing factors and users’ tourism intention, thus contributing to the academic research on emerging short videos and the endorsement of destinations promoted by technological innovation.

1. Introduction

Short video platforms are a relatively new global phenomenon with a rapidly increasing number of users ( Xie et al., 2019 ). Consumers and brands have become more inclined to communicate with each other through short video platforms ( Bailey et al., 2021 ; Kim et al., 2021 ; Wajid et al., 2021 ). In China, under the leadership of TikTok, Kwai and other platforms, short videos have quickly attracted people of all ages ( Du et al., 2022 ). Unlike mini movies or most YouTube videos, short videos are usually only 30 s to 1 min long, and their short duration fits in with today’s fast-paced life. Their rich and interesting background music has effectively enhanced users’ social ability ( Cao et al., 2021 ).

High-quality short tourism videos display the natural scenery and cultural highlights of tourist attractions through short video platforms such as TikTok ( Wei and Tong, 2019 ), and package the whole in a form suitable for dissemination, attracting tourists to visit these attractions ( Chen et al., 2022 ). The precedent of successful tourism short video marketing, as in the case of the Chinese city of Chongqing ( Liu and Fu, 2021 ), has led more and more researchers to explore the impact of tourism destination short video factors on tourism intentions ( Cao et al., 2021 ; Li, 2021 ). However, the process of information search and consumption in the tourism field is complex, and more research is needed on how short videos affect tourism intentions ( Pesonen and Pasanen, 2017 ; Alamäki et al., 2019 ).

From the perspective of tourism destinations and short video creators, it is important to understand how to develop video content based on potential consumers and what factors make the media effective ( Yang et al., 2022 ). After investigating TikTok, some scholars found that most of the short tourism videos on the platform lack interesting and professional content, and the tourism intention of users is rarely improved as a result ( Alamäki et al., 2019 ). Wang et al. (2022) used the extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to discuss the impact of perceived playfulness of short video on theme park tourism intentions. Although previous research verified the positive effect of short videos on potential tourists’ travel intention ( Shani et al., 2010 ; Rafael et al., 2020 ; Wengel et al., 2022 ), there is a lack of research on the main factors by which such videos affect tourism intention. Short video producers need to consider the information they want to convey and how different types of people will handle it ( Watzlawick et al., 1967 ).

In this study, we investigated the basic information about the population, content and habits involved in browsing short tourism videos, as well as the impact of the technology and content of short videos on tourism intention ( Zhang et al., 2019 ; Wang, 2020 ; Yan, 2021 ). We construct an influencing factor model to describe how short videos affect users’ tourism intention based on the extended SOR model, to which we add factors of perceived enjoyment (PE), perceived professionalism (PP), perceived interactivity (PI), perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU). Although these factors are considered the potential key factors for adoption in many fields, they have never been tested in empirical research on the use of the SOR model, nor have they been tested in research on tourism intention. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the impact of these short video factors (PE, PP, PI, PU, PEOU) on users’ tourism intention. To this end, the core contribution of this study has two aspects:

• To develop the conceptual model by extending the SOR model with external factors related to short video and investigate the impact of short video on tourism intention.

• To investigate the proposed study framework using AMOS 26.0 and structural equation modeling (SEM).

The rest of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review through the lenses of short videos, tourism intention, and the SOR model. Section 3 tackles hypothesis development and the research model. Section 4 presents the research methodology, and Section 5 shows the results, which are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 provides the theoretical and practical implications. Section 8 demonstrates the limitations and offers future recommendations, and Section 9 concludes the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. short video research.

The rise of short video relies on the emergence of short video applications. The earliest short video application, Viddy, was founded in the United States in 2010 and officially released on April 11, 2011. This platform made it convenient for users to create and share videos. In 2015, some researchers defined short video as a video shot by a mobile device for rapid editing or beautification and social sharing, with a duration of 5–15 s ( Wang et al., 2015 ). Later, the Research Report on the Development of Short Video Industry ( Fu, 2019 ) suggested a broader duration of 5 min or less, defining short videos as those characterized by short duration, fast dissemination speed, low creation threshold and strong participation. Others have described short video as a new form of expression combining words and images. Its emergence benefits from the reduction of network fees, the acceleration of network speed and the popularity of various intelligent devices. Users can often search for like-minded others, socialize, learn, and express themselves through such media ( Li, 2018 ; Fu, 2019 ; Kim et al., 2021 ). Although researchers have different definitions of short video, they all include the following points: (1) a certain time limit, usually within 5 min and most often 15 s to 1 min; (2) simple production and editing processes that yield vivid, impressive content; (3) convenient dissemination and sharing, mainly on social media; and (4) meeting individual needs and resonating in the minds of viewers.

Compared with long videos, short videos have low dissemination cost and high efficiency, especially in meeting the entertainment needs of contemporary young people’s fragmented lifestyles. As the main consumers of tourism, the post-90s and post-00s are bound to bring about changes in the industry’s mode of dissemination ( Buhalis, 2000 ). Among those effects brought about by short video dissemination, the promotion of urban destinations is particularly prominent. Chongqing, Chengdu, Nanning and other cities have become “Internet-popular” cities through the promotion of short video platforms in 2021, objectively reshaping the cities’ image and promoting the dissemination of urban brand culture. However, the “virality” of urban culture also exposed the problems of lower popularity for content related to historical, cultural and natural/scenic attractions, along with platform homogenization and poor supervision within the short video ecosystem ( Li and Wang, 2019 ). Therefore, some researchers have made bold innovations in the originality, production and audio-visual language presentation of videos. They selected benchmark characters and cultural landmarks and integrated emotion, information and artistry into content creation, so as to explore the feasibility of recording and disseminating urban culture through short videos in the future ( Chen, 2018 ).

In the mobile Internet era, tourism short videos have gradually become an important channel for people to pursue freshness and satisfy curiosity. They are a convenient way for online potential tourists to find information about a destination ( Karpinska-Krakowiak and Eisend, 2019 ). Combining previous studies with the specific characteristics of tourism video content, we defined tourism short videos as short videos of local cuisine, urban or natural landscapes, or commercial or historical tourist attractions, uploaded or shared by the local government, enterprises, tourists and local residents, with the short video platform as the dissemination carrier. Recently, Zhang and Hu (2021) have also summarized three types of value characteristics of such videos, namely: the sensory experience creates a refreshing audio-visual feast, a large number of Internet content creators bring the diversity and richness of the tourism experience, and social interaction forms a more profound impression of the tourism destination.

2.2. Tourism intention research

The concept of tourism intention first evolved from consumers’ purchase intention. Gartner (1994) posited that tourism intention is tourists’ attitude toward a tourism destination. Chen and Tsai (2007) put forward that tourism intention includes two meanings: recommendation intention and revisit intention, which is the judgment of tourists on the possibility of revisiting a tourism destination or recommending that destination to others. Huang and Huang (2009) pointed out that tourism intention and motivation are closely related. Tourism motivation can drive tourism intention, which leads tourists to choose a given destination and generates purchase behavior.

Researchers mainly study tourism intention from four aspects: perceived value to tourists, tourism destination, environmental factors and social media. Under COVID-19, the research direction gradually turned to the factors influencing digital tourism intention. Influencing factors in cultural tourism intention have also drawn recent attention from researchers ( Miao, 2020 ; Bieszk-Stolorz et al., 2021 ). The Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model, first proposed by Woodworth in 1929, was initially used to explain and analyze the impact of environment on human behavior, then gradually developed into a basic model to study consumer behavior ( Woodworth, 1929 ). The model has been widely used in the research on tourism behavior intention and tourism behavior. He et al. (2021) found that when the tourism destination has a good reputation and high perceived service quality, tourists will have higher satisfaction and stronger environmental responsibility behavior. Based on the SOR model, Wang (2021) verified that the reference information of educational excursions has a significant influence on educational excursion intention by constructing the relationship model among subjective knowledge, reference information, perceived risk, perceived value and tourism intention. Table 1 summarizes the factors found to have a significant impact on tourism intention in some existing studies.

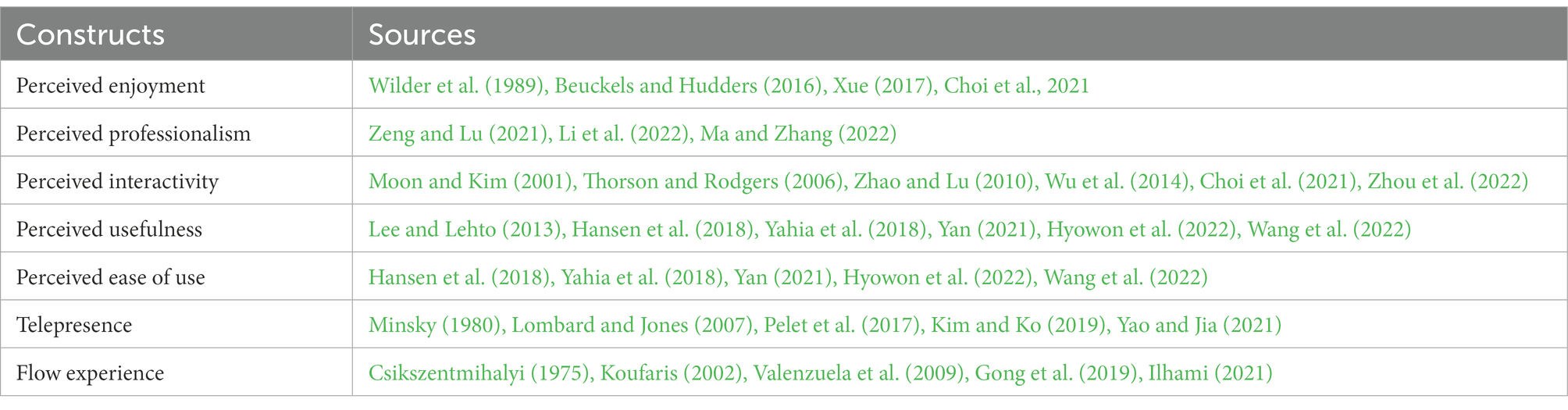

Table 1 . Constructs and their sources.

Many researchers have studied tourism intention from the personal perspective (tourism motivation, tourism attitude, self-efficacy, mental imagery, flow experience) and the environmental perspective (destination image, subjective norms, telepresence, perceived risk). At present, there are relatively few studies on the influence of short-video-related factors on tourism intention. As a new media form, short videos have great advantages in recording real performance of events and highlighting beautiful scenery, but it is unknown whether they can attract tourists. In addition, perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) from the TAM are often used as prerequisites for the study of behavioral intention. By combining the content characteristics of short videos with the theoretical factors of technology acceptance, this paper constructs an extended SOR model to explain and predict users’ tourism intention.

2.3. Stimulus-organism-response model and technology acceptance model

Mehrabian and Russell (1974) put forward the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) theory. Compared with the “stimulus–response” theory in behavioral psychology, the SOR theory pays more attention to the analysis and interpretation of the psychological activity process of the organism, systematically explains what psychological factors are responsible for the occurrence of individual behavior, and effectively clarifies the mechanism of influence between stimulus and individual behavior intention ( Donovan and Rossiter, 1982 ). In the context of cognitive learning the (SOR) model defines stimulus (S) as a factor that affects individual cognition or emotional activities. Organism (O) is an individual’s psychological or cognitive state formed by stimulus factors, while response (R) is an individual’s behavioral response realized through emotional and cognitive processes ( Donovan and Rossiter, 1982 ). SOR is suitable for studying consumer behavior intention because it focuses on people’s internal emotions and cognitive factors ( Sherman et al., 1997 ; Walsh et al., 2011 ; Tian and Lee, 2022 ).

Although the SOR theory was proposed prior to the advent of the Internet for offline behavior, it is now widely used in research into online user behavior. For example, Chen and Yao (2018) verified the impact of website framework quality on consumers’ impulse buying behavior in mobile auctions; Luqman et al. (2017) studied how transitional social use, transitional cognitive use and transitional hedonism caused users’ sense of technical stress and fatigue, which led to users’ voluntary abandonment of social networking sites. In addition, the SOR model proposes an internal mechanism, with both emotional and cognitive components, for factors influencing online user behavior, which allows for exploration of the internal psychological changes of consumers in more detail and improves the relevant research on consumer behavior. Tian and Lee (2022) proposed a study on the impact of social e-commerce fashion products on continuous purchase intention, and explored the relationship between social media interactivity, perceived value, immersive experience and continuous purchase intention. Based on the SOR model, other scholars have analyzed the impact of doctor information on patients’ cognitive trust and emotional trust, along with the impact of patient trust on doctors’ choice behavior, by using eye tracking technology and questionnaire survey methods, and found that emotional trust triggered by doctor information has a greater impact on patients’ choice behavior ( Shan et al., 2019 ). Others used the SOR model to analyze how the richness of social business characteristics affected consumer perception, cognitive factors and emotional factors, and how it affected consumer website stickiness ( Friedrich et al., 2019 ).

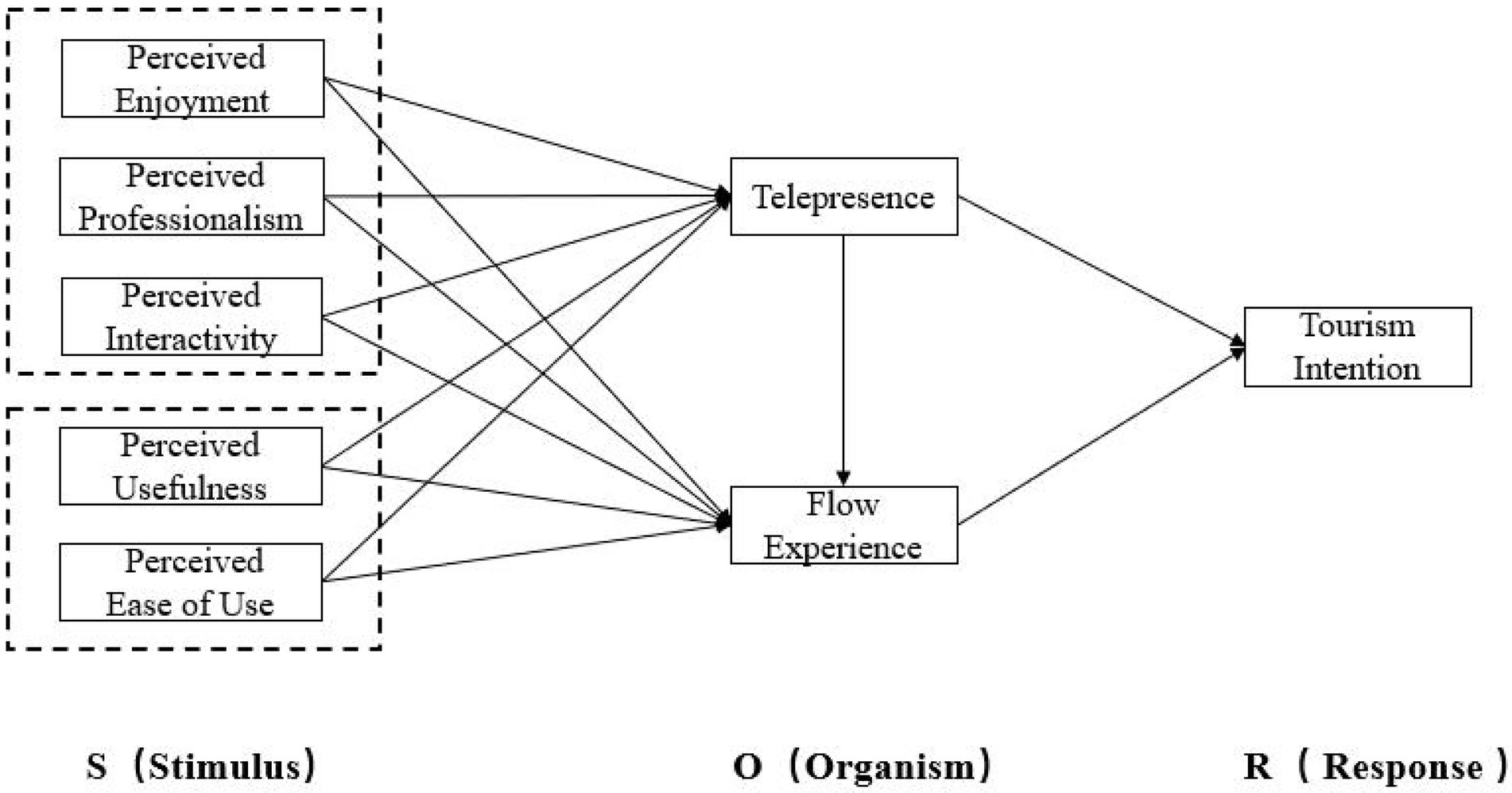

In keeping with previous studies, we choose the SOR model to explore the impact of short videos on tourism intention, using short videos factors as stimulus variables, telepresence and flow experience as organism variables, and tourism intention as the response variable. The research model for this study was the extended SOR model with the addition of the technology acceptance factors and short video variables.

Davis (1989) put forward the TAM in 1989 on the basis of rational behavior theory ( Davis et al., 1989 ). The main purpose of this model is to explain and predict users’ technology use behavior by studying the influencing factors of people’s acceptance and use of new technologies. The model believes that behavior intention generates use behavior, and behavior intention depends on individual perceived usefulness and behavior attitude. Among them, behavioral attitude is determined by perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness ( Davis, 1989 ).

In this paper, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) in the TAM model are used as perceptual variables to measure the flow experience and telepresence of users when watching tourism short videos, so as to judge the impact on travel intention.

2.4. Research hypotheses

Based on TAM and flow theory, this paper extends the SOR model by using the characteristic variables of short videos and constructs a research model of users’ tourism intention to verify the impact of perceived enjoyment (PE), perceived professionalism (PP), perceived usefulness (PU), perceived interactivity (PI), perceived ease of use (PEOU), telepresence (TP) and flow experience (FL) on users’ tourism intention (TI). The research model is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Research model of users’ tourism intention.

According to the tourism intention model, the following hypotheses are:

H1a : Telepresence (TP) has a positive impact on users’ travel intention (TI).

H1b : Telepresence (TP) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

H2 : Flow experience (FL) has a positive impact on users’ tourism intention (TI).

H3a : Perceived enjoyment (PE) has a positive impact on telepresence (TP).

H3b : Perceived enjoyment (PE) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

H4a : Perceived professionalism (PP) has a positive impact on telepresence (TP).

H4b : Perceived professionalism (PP) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

H5a : Perceived interactivity (PI) has a positive impact on telepresence (TP).

H5b : Perceived interactivity (PI) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

H6a : Perceived usefulness (PU) has a positive impact on telepresence (TP).

H6b : Perceived usefulness (PU) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

H7a : Perceived ease of use (PEOU) has a positive impact on telepresence (TP).

H7b : Perceived ease of use (PEOU) has a positive impact on flow experience (FL).

3. Methodology

3.1. participants.

The participants in this study are short video lovers—defined here as people of any age who often browse various new media platforms (TikTok, YouTube, etc.). Short video lovers are divided into two main categories: creators of original video content and the audience watching the videos. It has been found that the vast majority of users believe that they have the freedom to choose short video apps in terms of time, place and content—including relevance to personal interests and hobbies ( Chen and Chen, 2022 ). Therefore, users who often browse short videos may become the audience of tourism short videos.

The participants were required to meet the following criteria: (1) they were short video lovers who often browsed short video and (2) they volunteered for the study. We used the convenience sampling technique in collecting the primary data, which were from the Chinese city of Nanjing. Boomsma (1987) has suggested that, when using the maximum likelihood method to estimate the structural equation model, the sample size be 5–10 times the number of questionnaire items, with a minimum sample size of 200. To ensure adequate age coverage, the age of short video lovers is segmented as follows: under 18 years old, 18–30 years old, 30–55 years old and over 55 years old. In total, 421 short video lovers participated in this study, of which 395 participants’ data was deemed valid after eliminating those with obvious filling errors (e.g., identical answers from beginning to end, or too many missing values in the questionnaire). These respondents included 186 men and 209 women, for a nearly 1:1 gender ratio.

3.2. Instrument

In order to explore the influencing factors of short tourism videos on users’ tourism intention, this paper conducts a questionnaire survey of people who have a habit of browsing short videos. Based on previous studies, the authors understood the possible initial measurement items, conducted small-scale interviews with short tourism video lovers and professionals in relevant research fields, and then designed a questionnaire. The questionnaire partly adopted a Chinese translation of the scale from previous study, with some new items designed according to the interview results. The resulting closed questionnaire includes an item on “whether you have watched short tourism videos,” so as to eliminate invalid responses. To ensure the quality of the questionnaire, a small-scale pre-survey was carried out with 30 college students who often browse short videos, and the reliability and validity of the questionnaire were analyzed. In combination with the opinions of five professionals in the field, some measurement items involved in the questionnaire were modified to produce a formal questionnaire.

The questionnaire is divided into two parts, the first of which collects users’ basic information: gender, age, interest in tourism and viewing situation of short tourism videos. The second part surveys users’ tourism intention after browsing short tourism videos. The indicators representing the constructs were adopted from previous studies ( Table 1 ). The questionnaire uses a Likert 5-point scale with values ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

3.3. Data collection

The data was collected using a third-party online survey software “questionnaire star” ( www.wjx.cn ), which was unconnected to any institutional system from which the research samples were collected. In order to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the respondents, the questionnaire data did not collect the names, email addresses or phone numbers of the respondents. In addition, demographic data are collected by grade and subject.

Before data collection, the School of Management of Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications issued an official license for the project, so as to issue large-scale online questionnaires. Before filling in the questionnaire, participants were informed of the survey intention, and the meaning and content of the tourism short videos were explained, so as to ensure the respondents’ understanding of the questionnaire and the authenticity of the data in reflecting users’ tourism intention. The appraisers of the project shall collect the questionnaire from April 26 to May 3, 2022 and complete the screening inspection in time. It should also be mentioned that participants are told that if they do not want to fill out the questionnaire, they can ask to exclude themselves. Finally, the participants got the contact information of the researcher in case they wanted more clarification.

3.4. Data analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a multivariate analysis technique used to estimate various relationships among observed variables and latent variables ( Hoyle, 1995 ). A full SEM model or latent variable model consists of two parts: the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model relates measured variables to latent variables through confirmatory factor analysis models (CFA models), whereas the structural model links latent variables to one another, referred to as causal modeling or path analysis ( Yu and Shek, 2014 ). For this study, we estimate the structural equation model (SEM) using the maximum likelihood (ML) method, and mainly use the path analysis method to analyze users’ perception of travel intention after browsing short tourism videos through path plots and effect size. IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 and IBM SPSS Amos 26.0 were used to test the relationships between short video factors and tourism intention, including the process of full latent variable model testing that includes both CFA and path analysis.

3.5. Study variables

3.5.1. telepresence.

Minsky (1980) first proposed the concept of telepresence, which refers to the experience of presence that people have in a virtual environment rather than a real environment. Some researchers have defined telepresence as an individual’s perception of the environment, describing the degree of reality that people perceive in the virtual environment, also known as “immersiveness” ( Lombard and Jones, 2007 ; Yao and Jia, 2021 ; Zheng et al., 2022 ). Current studies reveal that telepresence affects users’ intention to purchase from shopping websites or to view live broadcasts. In different online situations, telepresence will significantly influence the flow experience of online users ( Pelet et al., 2017 ; Kim and Ko, 2019 ).

Short tourism videos can create a better experience for users to participate interactively in a strongly telepresent setting ( An et al., 2021 ). When users browse videos with a strong telepresence, they will feel that they are in the midst of mountains and rivers, resulting in a sense of freedom and relaxation throughout the body ( Taylor et al., 1998 ; Green and Brock, 2000 ; Chaulagain et al., 2019 ; Chi et al., 2020 ). Thus, telepresence is the feeling of being in a virtual environment: when users watch short videos, they will feel the scenery in front of them. Flow is an exciting and satisfying experience for users: when users watch short videos, they will feel very happy. A strong telepresence can encourage users to immerse themselves in the videos they browse and yearn for the scenes they depict, thus generating tourism intention. When users feel happy, relaxed and satisfied, telepresence has a positive influence on flow experience.

3.5.2. Flow experience

The concept of the flow experience originates from flow theory as proposed by psychologist Csikszentmihalyi (1975) , who defined flow as a feeling of fully investing one’s mental power in a certain activity. When flow occurs, people will be highly excited and satisfied. With the rapid development of the Internet, flow theory has seen wide use in research on consumers’ online activities, with the flow experience invoked to explain their online behaviors ( Koufaris, 2002 ; Valenzuela et al., 2009 ). Previous researches showed that there was a significant positive correlation between flow experience and intention ( Ilhami, 2021 ; Yao and Jia, 2021 ; Zheng et al., 2022 ). Once consumers enter the flow experience, they will be fully invested and even forget time and space in this highly concentrated state. The resulting pleasant emotion will stimulate consumers’ purchase intention ( Gong et al., 2019 ).

When browsing a short tourism video, users will be continually stimulated by the scenery and characters in the video. Spectacular scenery and rich scene switching make it easier to stimulate the enjoyment of the audience and make them enter a committed flow experience ( Collins et al., 2009 ). Moreover, users’ high satisfaction or high expectations can make it easier to enter a flow experience ( Hwang et al., 2011 ). When users browse short tourism videos and enter the flow state, they will unconsciously yearn for the tourism destination in the video, thus generating tourism intention.

3.5.3. Characteristic variables of short videos

The previous research on short video content mainly involves enjoyment, professionalism and interactivity ( Choi et al., 2021 ).

Perceived enjoyment, also known as perceived pleasure, is an internal motivation with a significant impact on users’ engaging in a certain activity; it can also be used to measure the change of flow ( Wilder et al., 1989 ). It is the degree of interest perceived by users when using a specific system for online activities. Some research has confirmed that the interest and entertainment value of a marketing platform’s content have a positive impact on the emotional arousal of users ( Beuckels and Hudders, 2016 ; Xue, 2017 ). When browsing a short tourism video, if the user thinks the content is very interesting, the perceived enjoyment will promote their immersion in it and have a positive impact on telepresence. Interesting and entertaining short video content arouses users’ emotions, and the perceived enjoyment will positively affect flow experience.

Content professionalism reflects the knowledge, experience and ability of video creators in a certain field and affects the evaluation and perception of users ( Li et al., 2022 ). When studying a popular science vlog, some researchers found that professional and authentic short video content can enable the audience to receive information to the greatest extent in a limited time ( Zeng and Lu, 2021 ; Ma and Zhang, 2022 ). Therefore, when the perceived professionalism of short video content meets users’ psychological expectations, it will generate the desire to be in the video environment. Perceived professionalism has a positive impact on telepresence. Convincing and professional short video content will stimulate users’ interest, and content professionalism will generate a positive flow experience.

Perceived interactivity refers to the communication and interaction between short video users ( Thorson and Rodgers, 2006 ; Zhao and Lu, 2010 ). Short video platforms provide channels for likes, forwarding and sharing, and users can leave messages in the comment area to participate in discussions or overlay real-time comments. High perceived interactivity means that users are willing to actively participate in the interaction, obtain the required information and complete the necessary work, which can deepen users’ understanding and use of the short video content ( Moon and Kim, 2001 ; Choi et al., 2021 ). Attractiveness and interactivity of short video platforms enhance users’ perceived interactivity and have a positive effect on telepresence. Perception of the utilitarian value embodied in interaction and the degree of user participation both have a positive impact on the flow experience ( Wu et al., 2014 ; Zhou et al., 2022 ).

3.5.4. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use

In TAM, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use significantly affect the intention of using technology ( Hansen et al., 2018 ; Yahia et al., 2018 ). When users believe that new technologies are useful and easy to use, it produces a certain degree of perceived pleasure, and they are more inclined to use those technologies ( Hyowon et al., 2022 ). Research on mobile short video software has found that these variables have the same relationship ( Yan, 2021 ; Wang et al., 2022 ).

In this study, perceived usefulness refers to users’ perception that short tourism videos are not only interesting, but also useful for individuals to obtain information, learn about tourism options and improve cultural literacy ( Lee and Lehto, 2013 ). Users are willing to be in the environment of short videos, and their perceived usefulness has a positive impact on telepresence. Users experience a certain degree of life happiness and satisfaction, so perceived usefulness has a positive impact on flow experience.

Perceived ease of use answers the question of how convenient it is to use short video apps or platforms. As mobile media that integrate editing, sorting, sharing and viewing, short video apps have simple operation and strong functionality ( Shang and Liu, 2021 ). Smooth and instinctive operation can help users enter a state of high telepresence, and perceived ease of use has a positive impact on telepresence. When a short video platform is easy to operate, it helps users enjoy the use process and positively affects the flow experience.

4.1. Sample characteristic analysis

Of the 395 participants who submitted a valid questionnaire, 186 were male (47.1%) and 209 were female (52.9%). Among them, the users of tourism short videos are mainly people under the age of 30, who accounted for 69.5% of our valid respondents; 22.1% were in the age group 30–50, and the remaining 8.4% were over 55. 80.6% of users said they like traveling, while only 6.3% of users said they do not. In terms of video browsing frequency, 28.9% of users often browse tourism short videos, 35.1% do so occasionally, 31.7% rarely, and only 4.3% never browse them. Most short video lovers browse tourism scenery (78.6%) and tourism strategies (82.6%), while fewer browse tourism history stories (49.1%) and other categories (19.4%). Most spend 5 to 30 min (69.4%) in a single browsing session, but some users indulge in short video for a long time (23.7%).

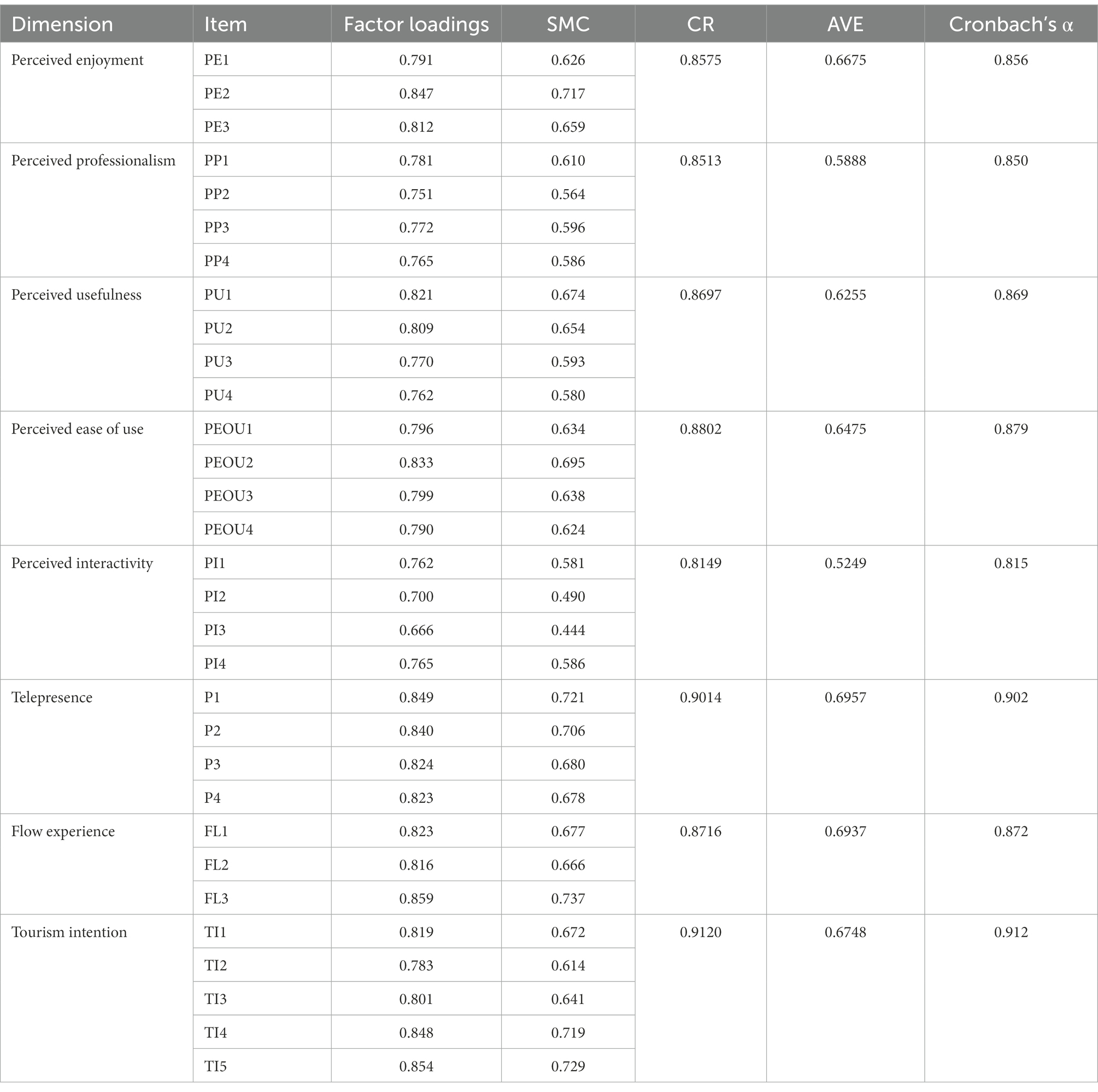

4.2. Reliability and validity analysis

The reliability of the scale is determined by the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α), average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). As shown in Table 2 , Cronbach’s α of perceived enjoyment, perceived professionalism, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived interactivity, telepresence, flow experience and tourism intention are greater than 0.8, the AVE of the factor load value of each measurement item is greater than 0.5, and the CR of each combination reliability is greater than 0.7, indicating that each measurement item of the questionnaire has very good reliability. Validity testing includes content validity and structural validity. After literature research, expert interview and pre-investigation, the design of this research scale extracts and modifies the items. The process is rigorous and has good content validity. The KMO is 0.982, greater than 0.8, the Bartlett’s sphericity value is 11,282.491 (DF = 465), and the statistical significance (P) is less than 0.001, indicating that the research data has high correlation and is suitable for factor analysis. In confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the factor load value of each item is greater than 0.7, indicating that the validity of the measurement model is good.

Table 2 . Reliability and validity analysis results of questionnaire.

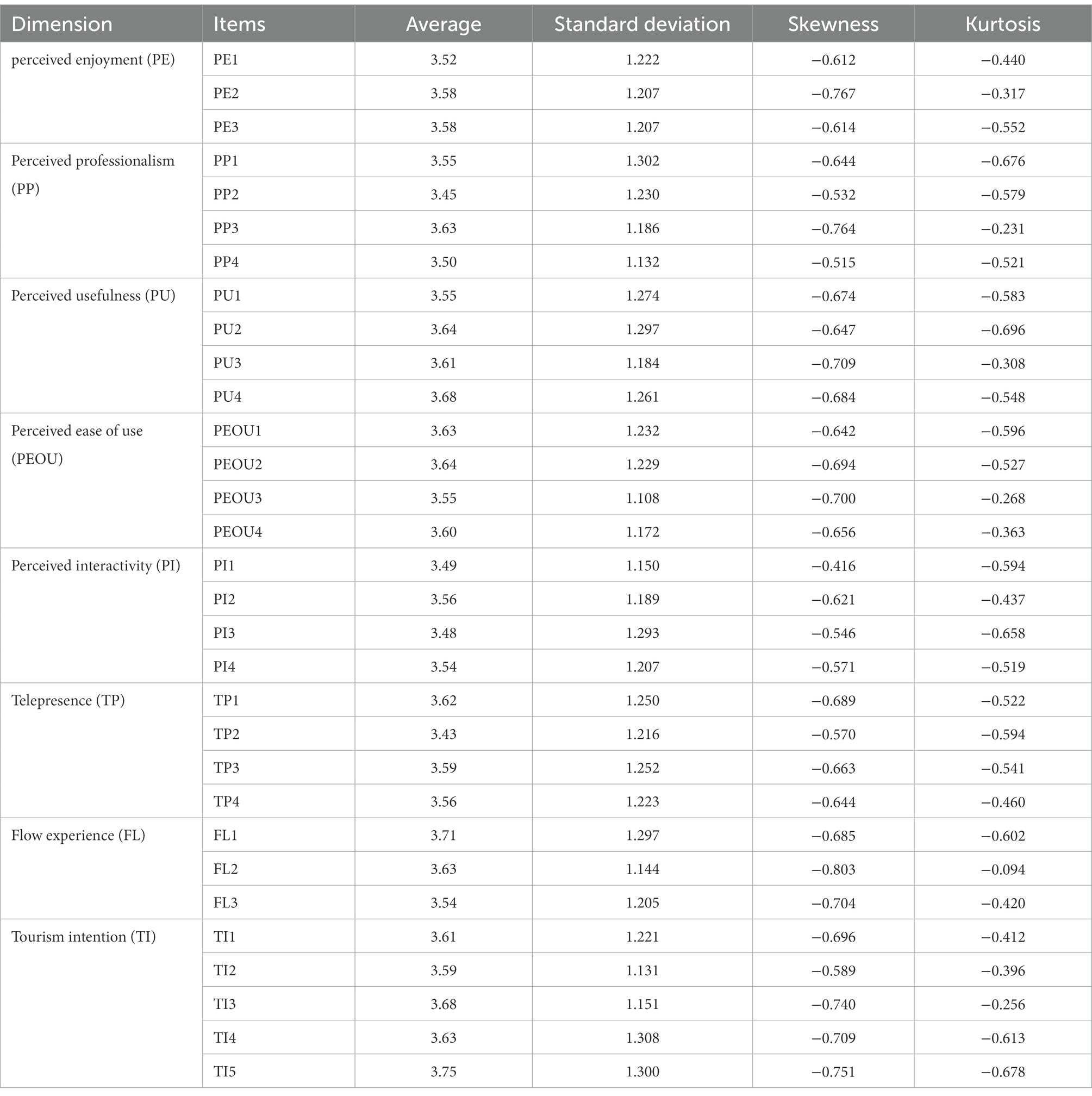

It can be seen from the above Table 3 that the absolute values of skewness coefficient and kurtosis coefficient are less than 1.96, which can be considered that this group of sample data conforms to the normal distribution and is suitable for the structural equation model method.

Table 3 . Test of normal distribution of questionnaire.

4.3. Structural model

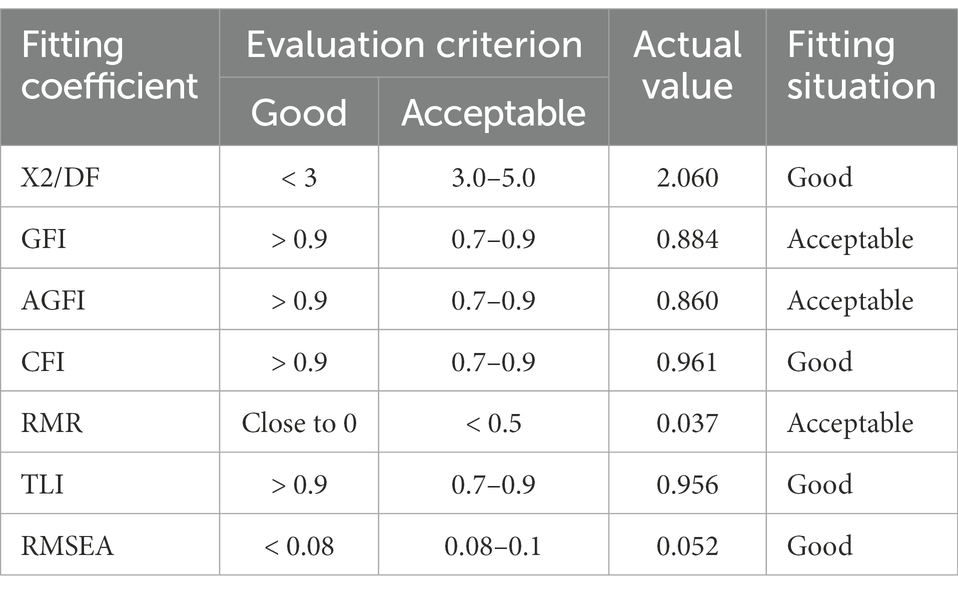

Amos26.0 is used to study the overall fitting evaluation and hypothesis test of the model. It can be seen from Table 4 that the model fitness meets the standard, indicating that the data collected and the model constructed match well, the proposed path assumption relationship is consistent with the actual situation, and the model coefficient results are accurate and effective.

Table 4 . Model fitness parameters.

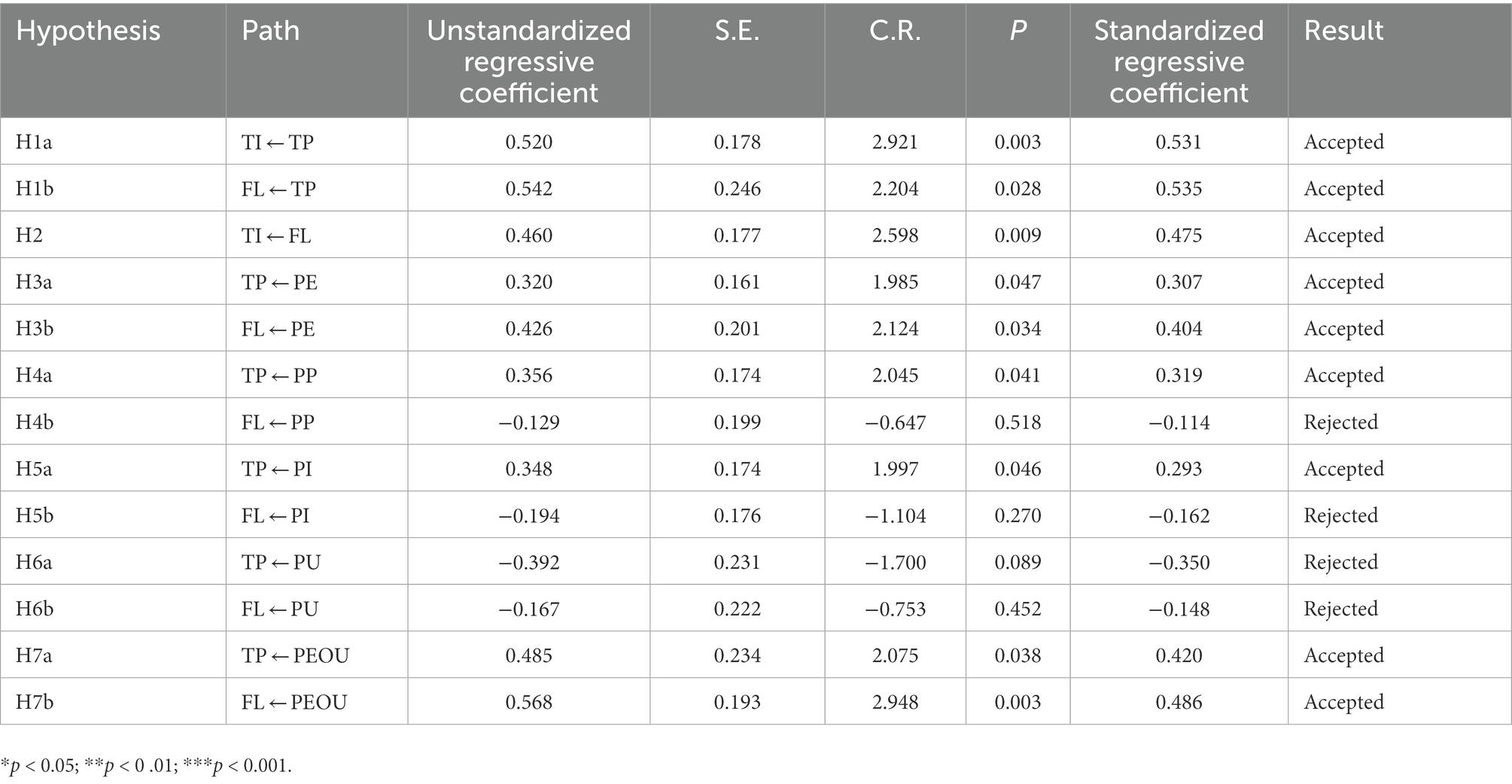

The degree of interpretation of the whole model and the significance of relevant assumptions are evaluated by path coefficient, C.R. value and p value, as shown in Table 5 . The absolute value of the critical ratio C.R. of 9 paths is greater than 1.96, and the significance probability value p is less than 0.05; these hypotheses are accepted. The absolute value of the critical ratio C.R. of 4 paths is less than 1.96, and the significance probability value p is greater than 0.05; these hypotheses are rejected (see Figure 2 ). The verification results in Table 4 show that some hypotheses proposed in this paper have passed the test.

Table 5 . Analysis of model results.

Figure 2 . Model path verification. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

5. Discussion

The aim of the present study is to investigate the influence of short video factors (perceived enjoyment, perceived professionalism, perceived interactivity, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness) on tourism intention by extending the SOR model with these factors. The findings revealed that perceived enjoyment and perceived ease of use are significant determinants of both telepresence and flow experience, which in turn positively associate with users’ tourism intention. This implies that the expectations for perceived enjoyment and perceived ease of use are significantly correlated with telepresence and flow experience in browsing short tourism videos. These results support the findings of a recent preliminary study which revealed that the convenience of a short video app or platform can significantly improve users’ sense of experience when browsing short videos, and smooth, instinctive operation can help them enter a state of high telepresence and strong flow experience faster ( Wang et al., 2022 ). These findings also reconfirm the conclusions of many previous researchers ( Beuckels and Hudders, 2016 ; Xue, 2017 ; Hyowon et al., 2022 ). Meanwhile, Choi et al. (2021) finds that the perceived enjoyment impacts of short video itself play a great auxiliary role in making it pleasant and interesting to browse short videos.

At the same time, the results show that perceived professionalism and perceived interactivity have a significant positive impact on telepresence, consistent with prior studies that found these same factors to have a positive impact on people’s intention to use websites ( Stavropoulos et al., 2013 ; Wu et al., 2014 ; Beuckels and Hudders, 2016 ; Zhou et al., 2022 ). Ma and Zhang (2022) believed that users tend to judge professionalism of video content in editing, special effects, narration, and copywriting, and that users’ recognition of high professionalism can quickly immerse them in short tourism videos. Interactivity is also reflected in overlaid real-time comments (“bullet screens”) on short videos, in the exchange and discussion in the comment area, and in likes, forwarding and sharing. Users’ active participation in videos can quickly immerse them in short tourism videos, thus generating telepresence and ultimately improving users’ tourism intention ( Choi et al., 2021 ).

Although most relevant studies show that users’ perceived usefulness of new technologies or systems will generate flow experience and telepresence in some settings ( Hansen et al., 2018 ; Yahia et al., 2018 ; Yan, 2021 ), the results show that this relationship does not necessarily apply to all people in any case. One possible reason is that the content of tourism short videos is commonplace among short video lovers, and they are no longer easily immersed in it. Another is that the relationship between perceived usefulness and telepresence and flow experience may depend on the motivation judgment of short video users ( Mohsin et al., 2017 ; Bayih and Singh, 2020 ). Additionally, the results revealed that a feature in the short video is more attractive or important, even if the content of the short video is considered useless, the user will still have a sense of flow and telepresence when watching the short video ( Skard et al., 2021 ). At the same time, since the samples of this study are concentrated on short video lovers, this relationship may not be established due to sample deviation.

Moreover, the results revealed that telepresence not only has a direct and significant positive impact on tourism intention, but also has an indirect impact on flow experience through significant prediction. The telepresence-intention link has previously been confirmed in consumer behavior research ( Pelet et al., 2017 ; Kim and Ko, 2019 ; Ye et al., 2020 ), and its reconfirmation in tourist behavior research further demonstrates the robustness of this association. Zheng et al. (2022) believed that telepresence is a state in which users can spontaneously be in the immersive state when browsing short videos. It is an important embodiment of users’ yearning for tourism destinations. This implies that when users immerse themselves in it, they will naturally forget the passing time and generate a sense of pleasure to a certain extent. That is, they enter the flow state. In both cases, the act of watching such videos will arouse users’ inner desire for tourism and generate tourism intention.

6. Conclusion

With the development of science and technology, new technologies such as 5G and virtual reality have entered people’s daily life. Short tourism videos have already had an impact on users’ tourism intentions, and new media and technologies have promoted the development of tourism in China and around the world. This research shows that the operation of short video platforms and users’ short video experiences have a significant relationship with users’ tourism intention. Short video platforms provide convenient operation, easy communication and sharing, and high-quality services to promote the tourism intentions of Chinese users. The findings show that short video characteristics and perceived ease of use have a significant impact on telepresence and flow experience, and thus have a significant impact on tourism intention. This study is noteworthy because short video has become an important way for most prospective visitors to understand tourist attractions in the post-pandemic era. Promoting the development of short tourism videos will be the key path to improve users’ tourism intention.

7. Theoretical and practical implications

This study holds several theoretical implications. First, the developed conceptual model is considered the first to combine short video factors and technology acceptance factors to extend the SOR model to predict users’ tourism intention. Second, the constructed model explains the changes in users’ tourism intention in the context of the global short video boom. Third, most of the established paths in the developed model are statistically positive. Thus, it is assumed that the short video factors and the SOR model are matched, which is one of the contributions of this study. Fourth, considering that few studies have extended the SOR model to address short video, future researchers may use this model to explore the impact of short video factors in other settings. Fifth, the outcomes of this study enhance the understanding of the key role that short video factors play in improving users’ tourism intention.