- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Is it Safe to Travel on an Airplane After a Stroke?

Many stroke survivors and families of stroke survivors worry about the safety of flying as a passenger in an airplane after a stroke. Is the concern warranted? It certainly is a common question, so common in fact, that a number of medical research studies have looked at this very question.

Can Flying Cause a Stroke?

Data shows that urgent medical ailments of all forms are relatively uncommon on airline flights, and the incidence of a stroke during a commercial flight is especially low.

An Australian group of medical researchers defined strokes related to air travel as any stroke occurring within 14 days of travel. After tracking 131 million passengers at Melbourne airport between 2003 and 2014, the researchers reported that stroke-related to air travel occurs in less than one in a million passengers. They found that that half of the people who had a stroke on a flight had a heart condition that is known to lead stroke . These heart conditions are fairly common, so the findings of the very low stroke rate suggest that there may not be a substantially increased risk of stroke from flying.

Another group of researchers from Spain found that a stroke occurred at a rate of one per every 35,000 flights. They found that over 70% of those who had a stroke on an airplane had carotid artery stenosis, which is narrowing of a blood vessel in the neck, a condition that is a risk factor for stroke.

Flying After a TIA or a Stroke

As it turns out, a history of stroke does not pose danger to the brain during an airline flight, and therefore, a past stroke is not a contraindication to flying on an airplane as a passenger.

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a mini-stroke that resolves without permanent brain damage. A TIA is very similar to a stroke and it is a warning of stroke risk. Most of the health conditions discovered during a medical TIA evaluation do not limit air travel.

However, it is important to note that a few of the medical disorders that lead to a TIA may pose a very small risk on airplane flights. These disorders include patent foramen ovale, paradoxical embolism, or hypercoagulability. If you have been diagnosed with any of these health conditions, you should get the appropriate medical treatment.

When It May Be Unsafe to Fly

Hypercoagulability is a condition that increases the tendency of blood clot formation. Several blood-clotting syndromes cause hypercoagulability.

Most strokes are caused by an interruption of blood flow due to a blood clot in the brain. Flying for long distances has been associated with an increase in blood clotting in those who are susceptible. If you have a hypercoagulable condition, it is best to talk to your healthcare provider about airplane travel and whether you need to take any special precautions.

What if a Stroke or TIA Happens in-Flight?

While it is unusual for a stroke to arise during flight, it does occur. When airline attendants are alerted of a passenger’s medical distress, they respond promptly, as they are trained to do.

If you or a loved one experiences a stroke on an airplane, nearby passengers and trained professionals are likely to notice and call for emergency medical help fairly quickly. On rare occasions, passenger flights have been diverted for medical emergencies, and emergency personnel can transport a passenger to a medical facility for diagnosis and treatment.

A Word From Verywell

A stroke causes a wide range of neurological deficits. Some of the disabilities that result from a stroke, such as impaired speech, vision changes, and trouble walking, may impair your ability to get around and communicate with others in the air travel setting.

Stroke survivors may suffer from deficits in spatial perception, which can increase the risk of getting lost in an airport. Communication problems after a stroke can lead to a misunderstanding of detailed flight information. Weakness and coordination problems can make it difficult to walk long distances through an airport. Consequently, for practical reasons, many stroke survivors should travel either with a companion or with professional assistance.

If you are a stroke survivor, you can travel safely with a reasonable amount of planning.

Álvarez-velasco R, Masjuan J, Defelipe A, et al. Stroke in commercial flights . Stroke . 2016;47(4):1117-9. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012637

Humaidan H, Yassi N, Weir L, Davis SM, Meretoja A. Airplane stroke syndrome . J Clin Neurosci . 2016;29:77-80. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2015.12.015

Cleveland Clinic. Transient ischemic attack (TIA) or mini stroke .

Messerli FH, Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Meier B. Economy class syndrome, patent foramen ovale and stroke . Am J Cardiol . 2017;120(3):e29. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.047

Dusse LMS, Silva MVF, Freitas LG, Marcolino MS, Carvalho MDG. Economy class syndrome: what is it and who are the individuals at risk? . Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter . 2017;39(4):349–353. doi:10.1016/j.bjhh.2017.05.001

By Heidi Moawad, MD Heidi Moawad is a neurologist and expert in the field of brain health and neurological disorders. Dr. Moawad regularly writes and edits health and career content for medical books and publications.

- Open access

- Published: 01 December 2020

Historic review: select chapters of a history of stroke

- Axel Karenberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2016-0701 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 34 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

5 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is no shortage of books, chapters and papers on the history of stroke focusing predominantly on the last 150 years and enumerating endless “milestones”. Instead of adding another article to this body of knowledge, this essay aims at ensuring awareness for the “big picture”, the “grandes routes”, and the “striking breakes” without overloading the reader with too much detail.

From a medical point of view, the history of stroke consists of two periods: the early era from the beginnings to 1812, and the following period from 1812 up to the present. It is argued that both periods require different methodical approaches, including disparate historiographical perspectives and varying forms of interpretation. In order to fully understand medical writings of the Greco-Roman era (Hippocratic writings, Galenic corpus) on “apoplexy”, a solid knowledge of ancient doctrines concerning health and disease is indispensable. During the Middle Ages, the spiritual perspective can be highlighted by focusing on miracle healing and patron saints. While stroke basically remained a conundrum for many doctors and patients in early modern times (ca. 1500–1800; Platter, Wepfer), the revolutionary perception and definition of the disease as a result of a lesion in the 1810s (Rochoux, Rostan) opened the door to a productive relationship of the upcoming discipline “neurology” with the natural sciences during the nineteenth century and beyond (Virchow et al.). The mostly unwritten history of stroke in the twentieth century should not only include the medical, but also the patient’s and the societal perspective.

A deeper insight into the recent and distant past will produce better educated strokologists – physicians who are able to put their own work into perspective.

“The true protagonists on the stage of medical history are the diseases”. Unfortunately, historical research often neglected this statement by French medical historian Charles Daremberg. We know a lot about famous physicians [ 1 ] and the social framing of medicine in the past [ 2 ], but comparatively little about the story of diseases themselves. Moreover, if and when they are studied by historians, the focus was and is usually put on epidemics and infectious diseases. 95% of the publications are on the history of plague, tuberculosis, syphilis and AIDS. In contrast, this essay argues that we can learn a lot about our medical past from non-epidemic, non-infectious illnesses. An excellent illustration of this approach is studying the history of stroke.

Stroke is today the second most common cause of death worldwide after heart disease, but before cancer [ 3 ]. In 2010, approximately 17 million people suffered a stroke, and another 33 million people have previously had a stroke and are still alive [ 4 ]. Obviously, we are really dealing with a “protagonist”. There seems to be just one open question to be resolved: how to assess appropriately the role of stroke in history?

Historical models and perspectives

From a medical point of view, the history of stroke comprises two periods: A first era from the beginnings to 1812, and a second timeframe from 1812 to the present (see below). However, these different time intervals require different approaches by the historian.

The modern period (i.e., the 19th and 20th centuries) can convincingly be described using a model of medical progress, which can also be called the “embryonic knowledge approach” [ 5 ]. The scientific findings of one decade can be seen as the nucleus of knowledge to be discovered in the next decade, and so on and so forth. In this perspective, Virchow’s description of thrombosis and embolism of 1846 is somehow the basis for almost all knowledge about these conditions up to the end of the twentieth century. This story of progress was mainly played out in hospitals, dissection rooms and labs, and these institutions were and are predominantly located in parts of Europe, Australasia, and the US. Thus the historian dealing with this modern period needs only a working knowledge in few modern languages to read the primary sources, if, for instance, she or he wants to find out since when blood pressure and cerebral haemorrhage were connected or how the story of secondary prevention developed.

However, this model of progressing science is not a very suitable one for the pre-1800 period. For centuries, there were no advancements at all in a modern sense of the word, and if so, they were very slow. Hence a different concept is needed for that period, and an appropriate one is the “strange object approach” [ 5 ]. According to this approach, a contemporary physician has to admit that her/his present-day medical knowledge is of very little help to understand peculiar early teachings about stroke, because they differ so much from the current actual knowledge.

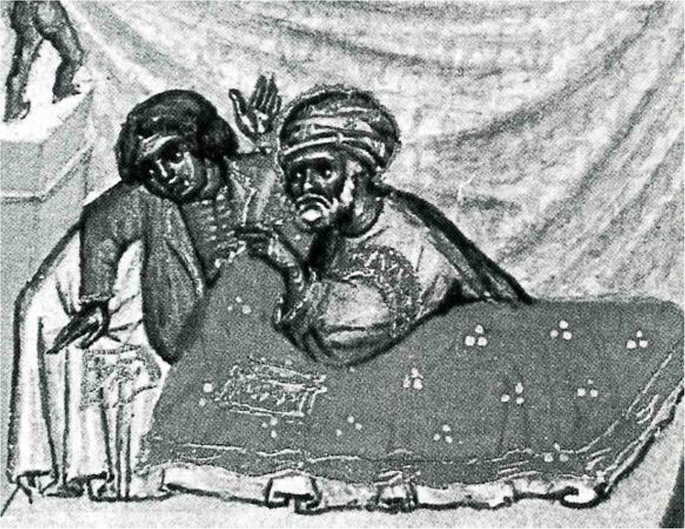

The only pre-modern illustration depicting a stroke victim provides an excellent example for a “strange object” [Fig. 1 ]. The patient suffers from a so-called “chronic stroke”. Some very strange things are happening: the physician, kneeling on the floor behind the sickbed, holds a hot iron in his hand and starts to cauterize the patient’s stomach (or head?) with the glowing instrument. The patient is not unconscious and doesn’t seem to suffer from paralysis, since he is defending himself. To understand this scenery, our present-day knowledge of stroke is obviously not sufficient. In this case, the historian has to act like an ethnologist – looking not only at the medical, but also at the cultural context. All in all, however, the early story of stroke is taking place in scriptoria and scholars’ parlors, not at the bedside of hospitals or in labs. The study of its Western variant requires a solid knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin. Additional reading ability in Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac, and other Semitic languages are quite helpful, too.

Treatment of chronic apoplexy. Miniature from ABU’L QĀSIM, Codex Series Nova 2641, Fol. 6ra. Reprinted in: (1979) Chirurgia. Lateinisch von Gerhard von Cremona. Vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. With permission of Austrian National Library, Vienna

Assuming we are able to combine these two different models successfully – from which point of view do we want to look at the evolving drama?

For doctors it seems clear that they are mainly interested in a medical perspective, in the reconstruction of changing medical knowledge. They will exclusively look at medical writings, perhaps also at medical illustrations, instruments, and institutions.

But this is of course not the whole story. What about patients suffering from stroke? Granted they are somehow part of the parcel, we have to broaden our historical horizon and consult their diaries, autobiographies and other source material [ 6 ]. Not an easy task: There are few so called ego-documents from the pre-1800 period and we are dealing with a condition including aphasic and agraphic disturbances.

How and where does society come into play? Every civilization is characterized by a spectrum of attitudes towards severe diseases of its members. Vice versa, severe diseases like stroke have a certain “image” generated within a social framework [ 7 , 8 ]. To understand societal and financial aspects, historians may therefore want to resort to various other sources including balance sheets of hospitals, communities or ministries of health as well as the archives of the health industry. Finally, for assessing the public image of stroke, fictional literature [ 9 , 10 ] as well as films, music and artwork constitute very important repositories.

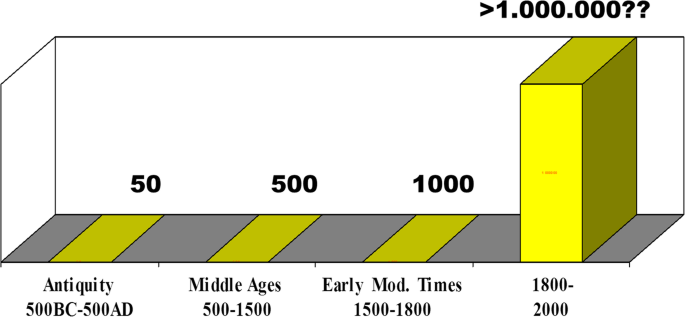

Why bother with all this theoretical stuff? It is important to understand that there will never be a single, all-encompassing history of stroke. There will only be various histories characterized by one or the other perspective and one or the other objective. This assertion is supported by a brief look at the number of available sources [Fig. 2 ]. Whereas the study of medical writings from antiquity, Middle Ages and Early Modern Times is manageable, no single historian will ever be able to read more than a minute part of the materials produced after 1800.

Estimated numbers of medical sources in the history of stroke across centuries. Drawing by the author

An outline of the history of stroke usually begins with the Greco-Roman civilization [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. It is, however, less conventional to follow the Socratic method based on the premise that one lived in a time of complete ignorance.

In antiquity, there were no dissections and no experiments besides some remarkable exceptions. The system of blood circulation was unknown, and regarding early antiquity no distinction could be made between arteries and veins. There was no consensus whether the brain or the heart was the instrumental organ for motor and sensory activities: whereas Plato, and most of the Hippocratic authors and Galen insisted on the brain [ 19 ], Aristotle and the physician-philosophers of the Stoic and Epicurean school favoured the heart [ 20 , 21 ] – for good reasons, by the way.

Nevertheless, the ancients came up with many insights worth mentioning today. First, they produced descriptions of the disease such as: “Pain suddenly seizes the head in a healthy person, and he at once becomes speechless … and gapes with his mouth” [ 22 ]. In a further Hippocratic writing, one can read: “In apoplexy, drowsiness befalls this patient, he is senseless … mild fever is present, and his body is powerless. He dies on the third or fifth day, and generally does not reach the seventh” [ 23 ]. The authors of these statements did not use the word stroke, but apoplexy, which was the preferred medical term to label stroke-like conditions up to 1800 [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The explanation for its use is simple. Many early civilizations were convinced that acute diseases with loss of consciousness were sent by the gods. In Homeric Greek, some four centuries before Hippocratic physicians appeared on the scene, stroke meant “plex” or “plexy” and god meant “theos” or “dios”. Thus “theoplexy” or “dioplex” were common denominations for stroke, and apoplexy is nothing but a secularized version for a “very severe blow”. The definitions mentioned above and the etymology of the word make it clear that the ancient term “apoplexy” and its modern sequel “stroke” are all but equivalent. Apoplexy is an umbrella term under which one can easily summarize what we today call stroke, but one can also subsume myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism triggering disturbances of consciousness.

Secondly, the Greeks realized that apoplexy was characterized by a different set of symptoms and a different course in comparison to various other medical conditions they called epilepsy, catalepsy, lethargy etc. [ 27 ]. Thirdly, ancient physicians wrote at length about treatment and prognostics including the world famous aphorism “It’s impossible to cure a violent attack of apoplexy, and difficult to cure a mild one” [ 28 ]. Finally, they set ethical standards how patients should be treated which did not change very much until today in many parts of the world.

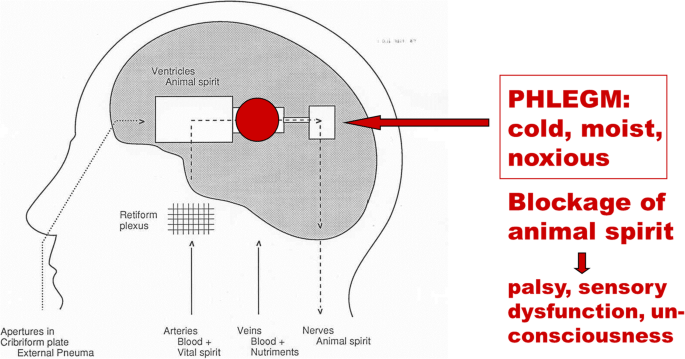

But how did Greco-Roman physicians explain the disease? Now it’s time to remember the “strange object approach”. Galen, a Greek physician practising and writing around the year 200 of our era in Rome, developed the idea that a vital spirit built in the heart was carried towards the brain via the arteries. In a structure called retiform plexus (which he found in several animal species in the region around the pituitary gland) this vital spirit was then transformed into the so-called animal spirit. Only the animal spirit was stored in the cerebral ventricles from where it acted on demand as a “fuel” for the transmission of motor impulses and sensory data to the periphery. That’s, in a nutshell, how the brain worked according to Galen [ 29 ].

In individuals with apoplexy, a noxious humour called phlegm accumulated in the body: “When the vessels drew phlegm into themselves, the blood must, on account of the coldness of the phlegm, stand more still than before and be cooled, and so, with the blood immobile, it is impossible for the body not to become still and numb … But if the phlegm predominates, the blood is cooled and congeals more, and if it reaches a certain stage of cooling and congelation, it congeals completely, the person becomes cold, and he dies” [ 22 ]. The accumulation of noxious mucus thus blocked the flow of the animal spirit, and the blockage eventually resulted in palsies, sensory dysfunctions, loss of consciousness, and possibly death [Fig. 3 ]. Phlegm was a cold, moist and viscous fluid which could accumulate in the brain when the body was exposed to too much cold, e.g. during the winter, in old age etc. [ 30 ]. This theory was the fundamental etiological doctrine of stroke and other brain diseases which dominated European thinking for 1500 years. No text on brain disorders up to 1750 can be understood without a solid knowledge of these principles.

Galen’s doctrine of apoplexy. Drawing by the author

This doctrine was also the basis for various therapeutic actions. A practising physician and adherent of this teaching had two basic options: either evacuation – meaning “cleansing brain and body” in order to get rid of the superfluous fluid, or counter-action – i. e. applying something hot and dry to combat the cold and moist humour. Evacuation and counter-action are two of the major meta-strategies of medical treatment until today. If one adds the four major realms of pre-1800 treatment – physical therapy, dietetics, herbal pharmacology and surgery – a wide spectrum of therapeutic measures is available, ranging from hot bathing to various surgical procedures including cauterization [ 31 ].

So what we see in ancient times is a rational, but speculative explanation of symptoms. This explanation was only loosely tied to the observation of nature, focused on “hidden causes” of disease but deeply embedded in ancient philosophy. Harmony between man and world, and harmony between the various parts of the body were its key principles. It is this holistic approach which makes certain aspects of ancient medicine still attractive for a couple of contemporary physicians representing alternative forms of medicine [ 19 ].

The medieval period

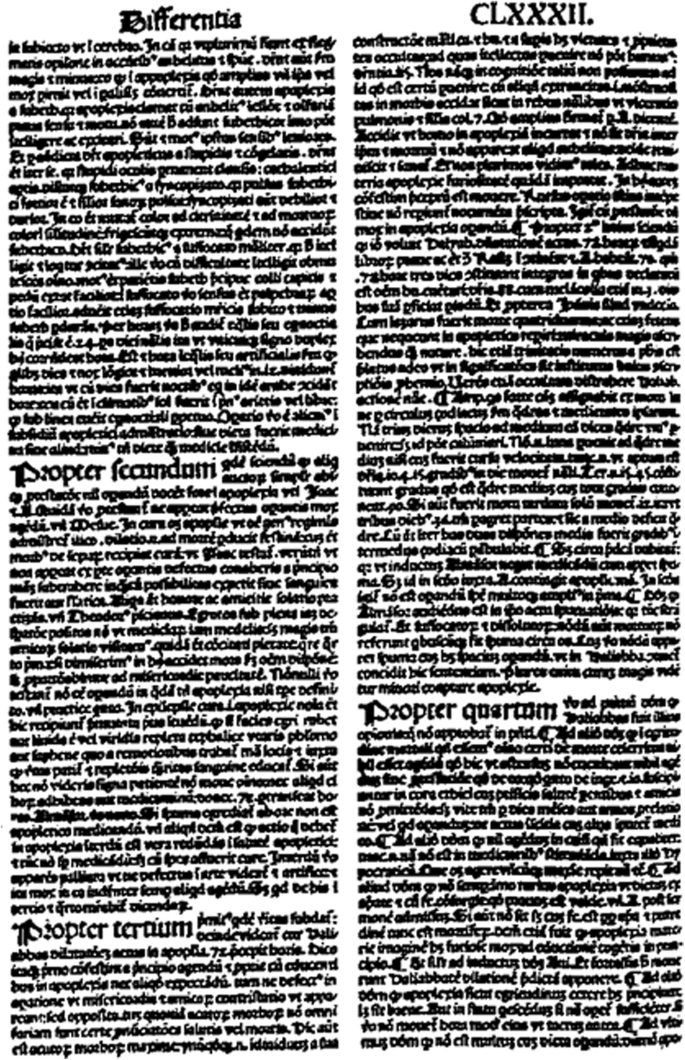

Between 500 and 1500 Galen’s brain-centred doctrine of neuropsychiatric symptoms was important, but it was, as mentioned before, not the only one. Aristotle and his followers had propagated a powerful cardiocentric theory: a teaching based on the assumption that the origins of motion, sensation and consciousness were located in the heart. “Tell me where is fancy bread, or in the heart or in the head”: with regard to stroke this question formulated by William Shakespeare centuries later was the neurological hotspot around the year 1000 [ 32 ]. Especially the best physician-philosophers of the rising Islamic civilization tried to reconcile both doctrines. Rhazes and Avicenna (ar-Razi and ibn-Sina) felt that Aristotle as well as Galen had good arguments [ 33 ]. From the eleventh century on, the issue was transferred from Bagdad and Cairo to the Latin West, to the emerging centres of learning in Italy, Spain, France, England, and finally the German speaking territories. Since there were still no dissections or experiments at hand, the problem couldn’t be solved in a modern way. But it was solved in a medieval way: by playing with words and quoting authorities. There are about a dozen truly scholastic texts on stroke, full of arguments and counter-arguments, pseudo-problems and pseudo-answers [ 32 ]. A folio page of a writing by the Italian physician-philosopher Pietro d’Abano [Fig. 4 ] [ 34 , 35 ], who taught in Padova in the early fourteenth century, provides insight into these sophisticated discussions and their fruitlessness from the patient’s point of view. By the way: the final medieval solution of the brain-heart-issue was to emphasize that a stroke began in the brain but terminated in the heart. This solution was accepted until the seventeenth century.

Folio page from Pietro d’Abano’s Conciliator (1496). With permission of the University and City Library of Cologne

Another “highlight” of the medieval era is the occurrence of miracles and patron saints. Early examples of faith healing in stroke and other medical conditions can be found in the Byzantine Empire, later ones in the Latin West and the Orthodox church of the East. These documents are ranking among the most important sources that have come down to us from these centuries. To quote just one miracle story which took place in Italy around the year 1250 in a Franciscan monastery, about one generation after St. Francis died:

“A certain young man … was subjected to a terrible fright that provoked mental confusion and paralysis of the right side of the body. Through his severe illness, he also lost hearing and the movement and sensation of the tongue. He had been confined to bed for some day in this pitiful state … One morning St. Francis appeared in the infirmary … stretched out his hand, running it lightly over the novice’s right side from head to foot, touching him gently, and placed his fingers in the young man’s ears, saying: ‘This shall be for you a sign that God has through me … completely restored your health’. With these words … the young man arose and entered the church with his health of body and mind, to the great astonishment of the brothers” [ 36 ].

This “case report” can be analysed in various ways [ 37 ]. A contemporary neurologist may think of a reversible ischemic neurological deficit or a psychogenic condition. A historian will certainly look for the theological and literary context. It is all but easy to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion here, also because this trove of miracle cures is largely unexplored yet.

A closing remark about stroke and religious healing in the Middle Ages. For epileptics, there were more than a dozen patron saints which could be addressed for prevention and/or cure of the illness [ 38 ]. For apoplectics, there was none. St. Wolfgang and St. Andreas Avellino only had a minor local significance [ 39 ]. For the scholar studying medieval medicine this shortage is quite surprising, and of course such a negative result needs an explanation. It certainly has to do with the high fatality rate of stroke: Patron Saints are no emergency room. But it may also be linked to the high rate of post-stroke disabilities hindering victims to travel to a place of pilgrimage. On the other hand, there was definitely a lack of commercial interest on the part of these places of pilgrimage – one of the first “management mechanisms” in the care of stroke patients.

Books and chapters about medicine in the Renaissance often use the metaphor of a “wind of change”, alluding to a fresh breeze blowing constantly over the European continent and sweeping away the medieval dust. But is that really true? As far as the history of stroke is concerned: yes, and no.

Following the first anatomical dissections of human bodies around 1300, from 1450 onward an increasing number of post-mortem examinations were carried out, leading to a better knowledge of brain anatomy and brain vasculature. About a century later, the first autopsies were performed in order to discover bodily changes in certain diseases: pathological anatomy was born. And in 1628 William Harvey used a variety of sophisticated experiments to prove that there is really something like a circulation of the blood, a circulation through the whole body including the head and the brain. New methods, revolutionary findings: but their significance for the understanding of stroke was practically zero, at least at the beginning.

In 1602, the Swiss physician Felix Platter carried out a brain autopsy after the death of one of his stroke patients. He summarized his findings of the post-mortem with the following words:“ a phlegmatic humour is obstructing the inner passages of the brain” [ 40 ]. This short statement highlights two pivotal insights that the study of historical diseases provides. First: every scientific observation is theory-laden, then and now. Second: obviously it is very difficult to get rid of traditional beliefs. Platter and practically all of his colleagues [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ] subscribed to Galen’s age-old idea that apoplexy was caused by phlegm in the cerebral ventricles. And what did brain autopsy reveal: phlegm in the cerebral cavities.

Yet brain autopsies plus the idea of a circulation marked the end of the pre-modern era of stroke. A true figure of transition was another Swiss physician named.

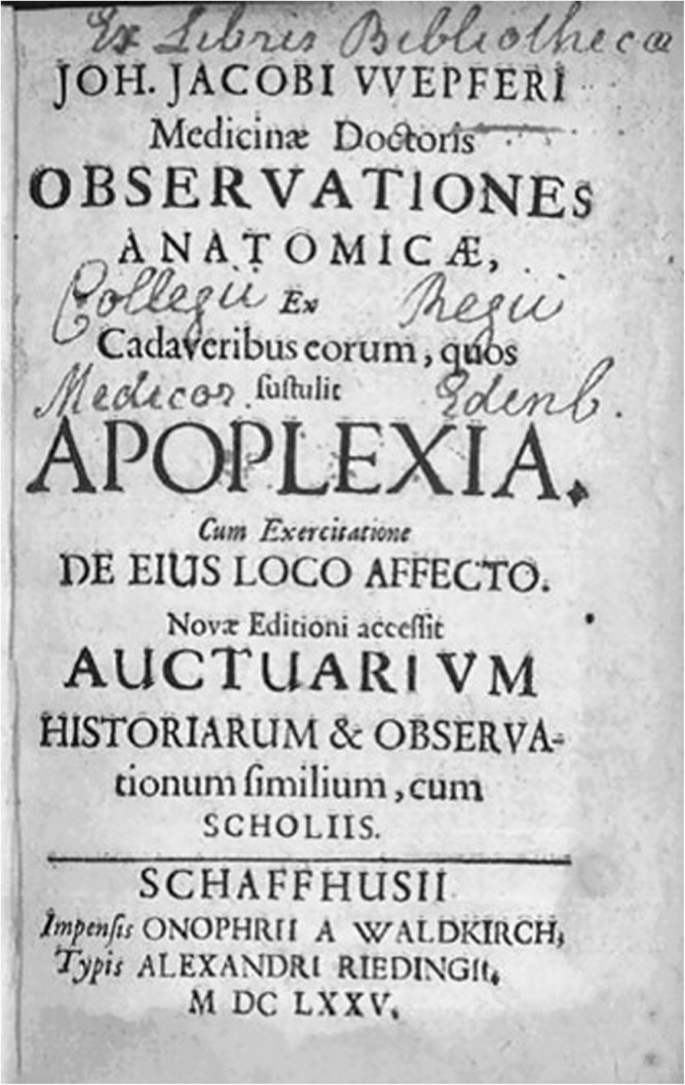

Johann Jakob Wepfer, who authored one of the most famous monographs on stroke of all times [Fig. 5 ]. For a long time, clinicians tended to classify Wepfer as a modernist and true reformer, for a couple of good reasons. With his research apoplexy became a cerebrovascular disorder. Moreover, he was convinced that the pathological changes were located in the cerebral substance and not in the ventricles. He also gave the hitherto most precise description of the encephalic arteries including the circle of Willis. In this context, Wepfer discovered during his dissections “pituitous formations” in brain arteries and hypothesized that these formations (clots?) play an important role in stroke. In addition, he found a hemorrhage in about 50% of the brains of stroke victims, thus proving that the rupture of a cerebral artery is responsible for the subsequent attack [ 45 ]. Wepfer was therefore praised as one of the harbingers of modern medicine [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. However, a careful reading of his 400-pages book [ 50 , 51 , 52 ] – a tedious task, because it is written in a difficult Latin – leads to striking results. Wepfer was a modernist, but at the same time still also a true follower of Galen with more than old-fashioned ideas on cerebral physiology and the etiology of stroke. According to him, the obstruction of brain arteries was harmful because the little clots blocked the flow of the vital spirit from the heart to the brain. A hemorrhage in the brain was disastrous because the animal spirit couldn’t flow freely towards the spinal cord and the nerves, and so on. Basically, Wepfer’s concept of stroke was still an ancient one dealing with humours and spirits, only supplemented by the latest anatomical and pathoanatomical discoveries.

Title page of Wepfer’s 1658 monograph on stroke. New edition 1675. With permission of the Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, University of Cologne

The modern era

The decisive difference between the pre-1800 and the modern period in the history of stroke is therefore not to be found in a single discovery or a set of new methods, but in a change of the basic notion of what a disease is [ 53 ]. From Galen to Wepfer, stroke (like many other neurological conditions) was defined as a collection of certain symptoms. With the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, stroke is for the first time defined as a result of a lesion. The morphological lesion, and only the morphological lesion, became the decisive criterion for an operational definition of stroke; the symptoms were now only seen as “indicatory signs”. Henceforth morbid anatomy, and nothing but morbid anatomy, became the key basis of all knowledge about stroke.

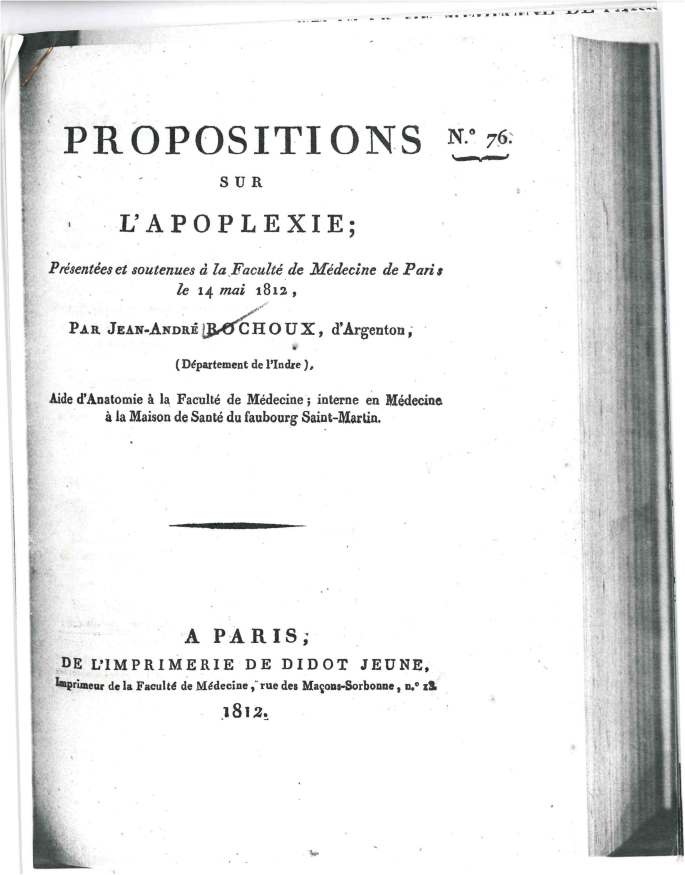

The birth of this new way of perceiving a disease is inseparably linked to the Paris school of medicine. Therefore, it is no surprise that the first truly modern definition of stroke is to be found in a French publication. In 1812, the young physician Jean-André Rochoux [ 54 ] produced what can be called the most important dissertation in the history of neurology [Fig. 6 ]. His text started with a phrase that is a platitude today, but indicated a scientific revolution when it was printed: “Apoplexy is a hemorrhage of the brain, by rupture, with more or less serious alteration of its substance” [ 55 ]. First Rochoux explained the lesion, its size, colour and location, then traced the signs and course of stroke, and concluded with a few remarks on treatment and prognosis. Undoubtedly, his dissertation and the monograph he produced 2 years later [ 56 ] are the first modern texts on stroke.

Title page of Rochoux’ 1812 dissertation on cerebral hemorrhage. With permission of the Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, University of Cologne

But Rochoux’ thorough exposition remained not the only one. In the very same decade, another young French doctor by the name of Léon Rostan came up with the idea that stroke must be the result of a softening of the brain (“ramollissement du cerveau”) [ 57 ]. In modern terms: ischemic infarction of the brain. Thus by 1820, the two basic modern concepts of stroke had been discovered. They were both offspring from the anatomico-clinical method, i. e. the comparison of post-mortem lesions with in-vivo symptoms. They were both found through hospital-based research and grounded on statistical observations. What followed during the whole 19th and a good part of the twentieth century was nothing but a refinement of these two basic concepts. Therefore, one can now really talk about progress and milestones: for example, the discoveries made by Rudolf Virchow who described, starting in 1846, arterial thrombosis and embolism and recognized the interaction between blood and arterial wall. Furthermore, the Berlin pathologist clearly showed that vascular occlusions caused infarction [ 58 ]. Again, this is a triviality today, but was a matter of acrimonious scientific debates in the 1840s.

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, medicine as a branch of knowledge was inextricably linked to the natural sciences. “No other theory as that of facts” was the positivistic credo of the epoch. A prominent German clinician put it even more bluntly: “Medicine will either be science or cease to exist”. Research on stroke profitted enormously from this positivistic movement. An increasing number of physicians, some of them specialized in neurology, contributed to the rapidly growing treasure of knowledge [ 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. It is impossible to enumerate all the important contributions, but one can at least emphasize some historical trends. From 1850 to 1930, vascular anatomy and clinical-anatomical correlations were of special interest, including various brain stem lesions. Between the 1920s and the 1970s, the pathophysiology of vascular lesions reached its hey-day including figures like the Frenchman Charles Foix, Kapitoline Wolkoff from St. Petersburg, and the Canadian Charles Miller-Fisher [ 13 ].

From about 1975 onwards, research on risk factors, stroke registries, randomized trials, databases, as well as a general momentum for “new treatments” can be observed [ 63 ]. So by the end of the twentieth century, stroke medicine became a subspecialty of neurology, theoretically as well as practically. And another important fact should be emphasized: For the first time, treatment of stroke was characterized by what one can call “limited therapeutic optimism” [ 64 ]. To a large extent, however, this evolution was due to the technical development of diagnostics: the history of twentieth-century medicine is essentially a history of technology. In the case of neurology, new technologies were available almost every decade, from hands-on spinal tap around 1900 to the most sophisticated brain visualizations 100 years later [ 65 ]. Sometimes it was even difficult for the doctor’s brains to keep up with the speed of technical innovation. But what is certain is that the history of stroke in the twentieth century remains to be written.

Conclusions

What are the take home messages of this historical tour?

It is a matter of personal taste if one likes the allegory of the dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants. However, knowledge about the history of one’s own field almost automatically leads to professional and personal modesty, which is always a good attitude, especially for physicians.

An intellectual tour through history may raise the awareness of how intimately we are connected to the intellectual, technical, and social context of our own epoch – we may or may not realize this frame. Galen, Wepfer, Rochoux, Rostan, Virchow and all the other important figures in the history of stroke: they were all products of their times sharing certain opportunities and certain limits – and so are we.

Perhaps the most valuable insight gained is that “unthinking” ideas of the past can be a key to great scientific success. The modern era in the history of stroke only came true because physicians of the early nineteenth century “unthought” all the misleading and constrictive presumptions which had been around for centuries. A fundamental conclusion therefore is: You can change history, yes you can!

This essay shall be concluded with an encouraging quote from the French poet André Gide expressing the very same idea in a much more elegant way:

“One does not discover new continents without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time” [ 66 ].

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Dumesnil, R., & Schadewaldt, H. (1970). Die berühmten Ärzte . Köln: Aulis Verlag Deubner & Co.

Google Scholar

Rosenberg, C. (1992). Framing disease . New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

World Health Organization (2018). The top 10 causes of death. Resource document . Geneva: WHO https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death . Accessed 10 May 2007.

Feigin, V. L., Forouzanfar, M. H., Krishnamurthi, R., Mensah, G. A., Connor, M., Bennett, D. A., et al. (2014). Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet , 383 , 245–254.

Karenberg, A., & Leitz, C. (2001). Headache in magical and medical papyri of ancient Egypt. Cephalalgia , 21 (9), 911–916.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Zimmermann, M. (2012). Narrating stroke: the life-writing and fiction of brain damage. Medical Humanities , 38 , 73–77.

PubMed Google Scholar

Moreno-Martinez, J. M., & Fernandez-Armayor, V. (2002). História e transcendência social da patologia vascular cerebral. Revista de Neurologia , 34 (11), 1092–1094.

Popovich, J. M. (2007). Coping with stroke: Psychological and social dimensions in U.S. patients. The International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research , 12 (3), 1474–1487.

Karenberg, A. (2011). Der Schlaganfall in der Literatur. In D. Schlaganfall-Gesellschaft (Ed.), 10 Jahre Deutsche Schlaganfall-Gesellschaft , (pp. 104–109). Berlin: Privatdruck.

Fischbein, M. (1965). Strokes. 1. Some literary descriptions. Postgraduate Medicine , 37 , A194–A198.

McHenry, L. C. (1981). A history of stroke. International Journal of Neurology , 18 (3–4), 314–326.

Gawel, M. (1982). The development of concepts concerning cerebral circulation. In F. C. Rose, & W. F. Bynum (Eds.), Historical aspects of the neurosciences , (pp. 171–178). New York: Raven Press.

Fields, W. S., & Lemak, N. A. (1989). A history of stroke. Its recognition and treatment . New York: Oxford University Press.

Quest, D. Q. (1990). Stroke: a selective history. Neurosurgery , 27 (3), 440–445.

Dening, T. R. (1995). Stroke and vascular disorders. In G. E. Berrios, & R. Porter (Eds.), A history of clinical psychiatry , (pp. 72–85). London: Athlone.

Heckmann, J. G., Erbguth, F. J., Hilz, M. J., Lang, C. J. G., & Neundörfer, B. (2001). Die Hirndurchblutung aus klinischer Sicht. Historischer Überblick, Physiologie, Pathophysiologie, diagnostische und therapeutische Aspekte. Medizinische Klinik , 96 (10), 583–592.

Warlow, C., van Gijn, J., Dennis, M., Wardlaw, J., Bamford, J., Hankey, G.,Sandercock, P., Rinkel, G., Langhorne, P., Sudlow, C, Rothwell, P. (2008). Development of knowledge about cerebrovascular disease. In: C. Warlow, J. Van Gijn et al. (Eds.). Stroke: practical management. 3rd ed.(pp. 7–34). Oxford: Blackwell.

Storey, C. E., & Pols, H. (2010). A history of cerebrovascular disease. In S. Finger, F. Boller, & K. L. Tyler (Eds.), History of neurology , (pp. 401–415). Edinburgh: Elsevier [Handbook of clinical neurology, 95].

Rose, F. C. (1994). The neurology of ancient Greece – an overview. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 3 (4), 237–260.

Finger, S. (1994). Origins of neuroscience. A history of exploration into brain function . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moog, F. P., & Karenberg, A. (2006). Aristotle on stroke. Sudhoffs Archiv , 90 (1), 123–124.

Hippocrates, Vol. V (1987). Diseases II. With an English translation by P. Potter . Cambridge: William Heinemann [The Loeb Classical Library, 472].

Hippocrates, Vol. VI (1988). Diseases III. With an English translation by P. Potter . Cambridge: William Heinemann [The Loeb Classical Library, 473].

Clarke, E. (1963). Apoplexy in the Hippocratic writings. Bulletin of the History of Medicine , 37 (4), 301–314.

Pound, P., Bury, M., & Ebrahim, S. (1997). From apoplexy to stroke. Age and Ageing , 26 , 331–337.

Patsioti, J. G., & Rose, F. C. (1995). What did the Greeks mean? Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 4 (1), 67–76.

Moog, F. P., & Karenberg, A. (1997). Die Apoplexie im medizinischen Schrifttum der Antike. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie , 65 , 489–503.

Hippocrates, Vol. IV (1959). Aphorisms. With an English translation by W.H.S. Jones . Cambridge: William Heinemann [The Loeb Classical Library].

Rocca, J. (2003). Galen on the brain. Anatomical knowledge and physiological speculation the second century AD . Leiden: Brill.

Karenberg, A. (1994). Reconstructing a doctrine: Galen on apoplexy. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 3 , 85–101.

Karenberg, A. (1999). “Einen schweren Schlaganfall zu heilen ist unmöglich, einen leichten nicht einfach”. Zur Therapie der Apoplexie im medizinischen Schrifttum der Antike. In: J. M. Ternes (Ed.), La thérapeutique dans l’Antiquité. Pourquoi? Jusqu’où? (pp. 61-78). Luxemburg: Études luxembourgoises d’histoire et de littérature romaine, 3.

Karenberg, A., & Hort, I. (1998). Medieval descriptions and doctrines of stroke: Preliminary analysis of select sources, part I-III. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 7 (3), 162–200.

Karenberg, A., & Hort, C. (1999). Zwischen Galenismus und Aristotelismus: Der Schlaganfall in der islamischen Medizin des Mittelalters. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Nervenheilkunde , 5 , 109–118.

Pietro d’Abano (1496). Conciliator differentiarum philosophorum et praecipue Medicorum … Venetiis, Bonetus Locatellus.

Paschetto, E. (1984). Pietro d’Abano medico e filosofo . Firenze: Nuovedizioni Enrico Vallecchi.

Analecta Franciscana, Tomus X (1941). Legendae S. Francisci Assisiensis saeculis XIII et XIV conscriptae … Fasciculus V: S. Bonaventura, Doctor Seraphicus, Legenda maior et Legenda minor S. Francisci … Ad Clara Aquas (Quaracchi): Typographia Coll. S. bonaventura e.

Moog, F. P., & Karenberg, A. (2003a). St. Francis came at dawn – The miracolous recovery of a hemiplegic monk in the middle ages. Journal of the Neurological Sciences , 213 , 15–17.

Frey, E. F. (1979). Saints in medical history. Clio Medica , 14 (1), 35–70.

Moog, F. P., & Karenberg, A. (2003b). Heilige als Patrone gegen den Schlaganfall. Early Science and Medicine , 8 , 196–209.

Platter F (1662). Praxeos seu de cognoscendis, praedicendis, praecavendis curandisque affectibus homini incommodantibus tractatus tres . Basel 1602-1608. Translated into English under the title: A Golden Practice of Physick . London: Peter Cole.

Coturri, E. (1971). La malattia apoplettica nel pensiero die G. B. Morgagni. In: Atti del 21. Congresso Nazionale di Storia della Medicina , Taranto-Bari, 1969 (pp. 324-329). Roma.

Jarcho, S. (1980). Some lost, obsolete, or discontinued diseases: serous apoplexy, incubus, and retrocedent ailments. Transactions and Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia , 2 (4), 241–266.

Schutta, H. S. (2006). Seventeenth century concepts of “apoplexy” as reflected in Bonet’s “Sepulchretum”. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 15 (3), 250–268.

Schutta, H. S. (2009). Morgagni on apoplexy in De Sedibus: a historical perspective. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 18 (1), 1–24.

Wepfer, J. J. (1658). Observationes anatomicae, ex cadaverum eorum, quos sustulit apoplexia. Cum exercitatione de eius loco affecto . Schafhusii: Typis J.C. Suteri.

Donley, J. E. (1909). John James Wepfer, a renaissance student of apoplexy. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital , 20 , 1–9.

Fischer, H. (1931). Johann Jakob Wepfer (1620–1695). Ein Beitrag zur Medizingeschichte des 17. Jahrhunderts . Zürich: Rudolf.

Major, R. H. (1978). Classic descriptions of disease , (3rd ed., ). Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

Gurdjian, E. S., & Gurdjian, E. S. (1979). History of occlusive cerebrovascular disease. I. From Wepfer to Moniz. Archives of Neurology , 36 , 340–343.

Karenberg, A. (1998). Johann Jakob Wepfers Buch über die Apoplexie (1658). Kritische Anmerkungen zu einem Klassiker der Neurologie. Nervenarzt , 69 , 93–98.

Mani, N. (1978). Pathogenese, Diagnose und Prognose der Apoplexie bei Johann Jakob Wepfer (1658). In C. Habrich, F. Marguth, & J. H. Wolf (Eds.), Medizinische Diagnostik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Festschrift für Heinz Goerke zum sechzigsten Geburtstag , (pp. 235–239). München: Fritsch.

Mani, N. (1982). Biomedical thought in Glisson’s hepatology and in Wepfer’s work on apoplexy. In L. G. Stevenson (Ed.), A celebration of medical history , (pp. 37–68). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Foucault, M. (1963). Naissance de la clinique: Une archéologie du regard médical . Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Walusinski, O. (2017). Jean-André Rochoux (1787-1952), a physician philosopher at the dawn of vascular neurology. Revue Neurologique (Paris) , 173 (9), 532–541.

CAS Google Scholar

Rochoux, J.-A. (1812). Propositions sur l’apoplexie. Thesis no. 76 . Paris: De l’Imprimerie de Didot jeune.

Rochoux, J.-A. (1814). Recherches sur l’apoplexie . Paris: Méquignon-Marvis.

Poirier, J., & Derouesné, C. (2000). La neurologie à l’Assistance Publique et en particulier à la Salpêtrière avant Charcot. L’exemple de Rostan et du ramollissement cérébral. Revue Neurologique (Paris) , 156 (6-7), 607–615.

Schiller, F. (1970). Concepts of stroke before and after Virchow. Bulletin of the History of Medicine , 14 (2), 115–131.

Paciaroni, M., & Bogousslavsky, J. (2009). How did stroke become of interest to neurologists? A slow 19th century saga. Neurology , 73 , 724–728.

Bruetsch, W. L. (1971). Richard Bright (1789-1858) and apoplexy. Transactions of the American Neurological Association , 96 , 213–215.

Schutta, H. S. (2017). Richard Bright’s observations on diseases of the nervous system due to inflammation. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences , 27 (2), 165–185.

Engelhardt, E. (2017). Apoplexy, cerebrovascular disease, and stroke: Historical evolution of terms and definitions. Dement Neuropsychology , 11 (4), 449–453.

Caplan, L. R. (2004). Cerebrovascular disease: historical background, with an eye to the future. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine , 71 (suppl. 1), 822–824.

Licht, S. (1973). Stroke: a history of its rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 54 , 10–18.

Karenberg, A. (2008). Von der Traumdeutung zum Neuroenhancement. Die Entwicklung der Nervenheilkunde. In D. Groß, & H. J. Winckelmann (Eds.), Medizin im 20. Jahrhundert , (pp. 60–77). Redd Business Information: München.

Gide, A. (1925). Les faux-monnayeurs . Paris: Gallimard.

Download references

Acknowledgements

No funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, Medical Faculty, University Hospital Cologne, University of Cologne, Joseph-Stelzmann-Str. 20, 50931, Köln, Germany

Axel Karenberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

It’s a one-author paper. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

The author is Specialist for Neurology and Specialist for Psychiatry as well as Professor of the History of Medicine.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Axel Karenberg .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Karenberg, A. Historic review: select chapters of a history of stroke. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00082-0

Download citation

Received : 22 May 2020

Accepted : 22 July 2020

Published : 01 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00082-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Stroke/history

- Cerebrovascular disorders/history

- Intracranial hemorrhages/history

- Paralysis/history

- Neurology/history

- Stroke/pathology

- Historical article

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Can You Fly After a Stroke?

by Flying Angels Editorial Team | Jun 22, 2020 | News & Resources

Many stroke survivors worry about if and when they can fly after a stroke. Medical research shows a person can fly after a stroke, but they should consider the type of stroke they had, how long it’s been since the stroke and whether they want medical travel assistance during the flight.

If you plan to travel after having a stroke, it’s comforting to know that research has found having a history of a stroke does not put a person in danger during an airline flight. Having a past stroke does not mean a person should not fly.

But if a stroke has been more recent or a person simply has concerns about flying, they should consider several factors before booking their trip.

Can I Hire a Nurse to Fly With Me?

Factors For Flying After a Stroke

Strokes vary in type and severity. Stroke victims should consider their own unique circumstances. Experts do not have hard and fast rules that apply to everyone who has had a stroke. But the following factors can help you decide about flying.

Type of Stroke

The advice on when to fly could depend on the stroke. A full stroke involves the sudden loss of blood flow to the brain. However, many people experience a transient ischemic attack (TIA), which is known as a “mini-stroke” that resolves without permanent brain damage.

A TIA is like a stroke and considered a warning sign of stroke risk. Also, some medical disorders that lead to a TIA could pose a “very small risk” on flights, according to research compiled by Very Well Health. Those conditions include patent foramen ovale, paradoxical embolism or hypercoagulability. It’s important to know if you have those conditions.

Get Help Leaving the Hospital After Discharge

Timing of Stroke

Experts may vary on when they recommend you can fly. The Stroke Association recommends that it is “probably best to avoid flying for the first two weeks. This is the time when your problems are likely to be most severe and other conditions related to your stroke may come up.”

In the most severe stroke cases, patients may want to wait as long as three months. However, with a TIA, many people are safe to fly in 10 days.

Before booking a flight, people should consult with their doctor.

Long Distance Medical Transport Cost

Medical Assistance For A Flight

Some people who have had a stroke may prefer to hire medical professionals to fly with them. Doing so provides them a high degree of security in making the flight and ensures they get proper medical care if needed. Such help is found with non-emergency transport (NEMT) companies like Flying Angels.

Flying Angels provides a number of services that can support stroke victims when they fly. A Flight Coordinator books your flight, sets up all the arrangements with both airports and airlines, gets you through security and provides a flight nurse to help you throughout your journey. The company hires only nurses with a great deal of experience working in emergency rooms and who have training in providing medical care at high altitudes.

Medical Transportation Options Explained

Stroke survivors may face challenges, but they still can live a full life. As with any serious condition, those who have had a stroke need to practice patience and planning. Travel by flight is certainly doable if they have the right amount of support. Consulting with a doctor and a medical transport service can give people the answers they seek about flying after a stroke. They also can provide the comfort, care and support they need to make the journey.

Popular Articles

- International Patient Transport: A Compassionate Solution for Returning Patients Home

- The Role of NEMT in Patient Centered Care for Long Distance Transfers

- Hiring a Medical Escort: Essential Questions and Guidance

- https://www.facebook.com/FlyingAngelsInc/

- https://www.linkedin.com/company/flying-angels/

Travelling after stroke

Everyone needs a holiday! It is good for your mind and body to rest and relax!

You may not be thinking about travelling immediately after your stroke but at some point you may consider taking a holiday. You may want to travel for rest and relaxation, to see new places, or visit family and friends.

Your doctor will let you know if it is safe for you to travel. Your healthcare team can also give you some tips to make travelling easier.

What do I need to know for traveling after stroke?

Considering your needs and planning ahead can help you have a safe and enjoyable holiday. It may be helpful to speak with your health care team for suggestions to make travel easier.

Learn from the experience of others. You can get ideas and suggestions from other people who have had strokes about what has worked well for them while travelling. For example, you may find answers to your travel questions at a peer support group or online.

Here are some things to consider when looking for a place to stay:

- Accessible bathroom. They offer grab-bars and toilet seats

- Elevator If there is no elevator, ask for a room on the ground floor

- Restaurants nearby. Stay in places that are close to things to do

- See online photos of the hotel. This helps you decide what you will need to bring

- Call and ask questions before you book your room

You may consider:

- Taking your own chair. Bring a folding cane-seat or a rollator if you can only walk short distances. Chairs or benches may not always be available when you need to take a break

- Renting a wheelchair or scooter. If you need to travel a long way

What are some tips for riding on an airplane?

- Choose a non-stop flight. If you have to make a connection, try to get more time between flights. Call the airport to find out how far you need to go to get the connecting flight

- Choose an aisle seat. This helps to give you a bit more room.

- Use a carry-on. Use a shoulder bag or back pack. Pack it with basic toiletries, medications, and travel information

- Wear shoes that are easy to take on and off. This makes security checks easier

- Travel with someone. It helps to travel with someone who can help you

Here are some tips at the airport:

- Check-in as much luggage as you can. This means less to carry

- Give yourself extra time.

- Use early boarding. Flight attendants can help you board the plane if you are using a cane or wheelchair

- Use an airport rental cart. It is often easier to push one cart than manage many bags

Tips for travelling with aphasia:

Write down all your travel information. If you have aphasia you can show the airline personnel or the taxi driver the information, so they know how to direct you. Have all important addresses and phone numbers in your notebook.

Having read the information in this section, consider the following questions.

- Do I know if it is safe for me to travel after my stroke?

- Is it safe for me to travel by car, train, boat or plane?

- Is there anything specific I need to be aware of when travelling after a stroke (for example: precautions, medications, vaccinations)?

- Do I know how to plan a safe trip?

- Can I make sure that my needs will be met at my destination (for example, equipment and accessibility needs)?

- Do I need to call ahead before I leave to ensure things are in place at my destination?

- Do I have travel insurance?

- As a caregiver, do I know what to do if something happens while we are away from home?

Where to get more information, help and support:

Ten Travel Tips for Stroke Survivors

Travel and Heart Disease

Travel precautions help people with heart disease

Traveling to a faraway place doesn’t need to be off limits because you have heart disease or are a caretaker of someone who has had a cardiac event like heart attack or stroke . A few simple precautions can help make your trip smooth.

Here are some travel tips:

- Keep medicines in their original, labeled containers. Ensure that they are clearly labeled with your full name, health care professional’s name, generic and brand name and exact dosage.

- Bring copies of all written prescriptions. Leave a copy of your prescriptions at home with a friend or relative in case you lose your copy or need an emergency refill. Download this medication chart (PDF) to keep track of your medicines.

- Ask your health care professional for a note if you use controlled substances, or injectable medicines, such as EpiPens and insulin. Tell your health care professional about your travel. Let your cardiologist or internist know where you’ll be. Your health care professional might know medical professionals or reputable heart institutes in the area you’re visiting if help is needed.

- Comprehensive travel insurance usually includes medical evacuation travel insurance. Coverage varies by plan, destination and duration of trip, so shop around. But the average cost is about $200, which is a small investment if it can cover tens of thousands dollars of potential medical expenses.

- Some health care professionals recommend taking a copy of your pertinent medical records with you while traveling.

High altitudes, exotic spots

Oxygen availability declines at higher altitudes, which can place unique stressors on the cardiovascular system. As such, patients who are at risk of or who have established cardiovascular disease may be at an increased risk of adverse events when staying at mountainous locations. However, these risks may be minimized by appropriate pretravel assessments and planning through shared decision‐making between patients and their managing health care professionals.

Talk to your health care team before your trip to understand what you should do to prepare. You may wish to gradually move up the mountain and acclimate at lower elevations before moving to the higher altitudes. People with coronary artery disease and angina should anticipate that reduced oxygen levels may increase angina. Your heart has to work harder, especially if you already have blockage. Watch out for shortness of breath or other symptoms that could indicate you’re tipping from a stable to an unstable state.

Be mindful of your fluid consumption and sodium (salt) intake if you have cardiomyopathy or a history of heart failure . A balanced fluid intake is important in these conditions.

If you’re traveling to a country where certain vaccines are needed to guard against disease, it’s not likely the immunization will affect your heart. The bigger concern may be consistent access to quality medical care.

Consider selecting destinations in parts of the world that both interest you and have many options for health care you may need while you are visiting.

Long distance precautions

Sitting immobile on long plane flights or car, train or bus rides can slightly increase a normal person’s risk of blood clots in the legs, but associated medical issues usually contribute to it. If someone has peripheral artery disease (PAD) or a history of heart failure, the clot risk increases. Recent surgery, older age and catheters in a large vein may also increase your risk of blood clots. Getting up and walking around when possible is recommended for long flights, just be sure the seatbelt light is not on when you do so. Stopping to take a quick break during long car rides may help as well.

Tell your health care professional about your travel plans to get the best advice on what precautions, if any, you may need to take. For example, some people might need compression stockings or additional oxygen. Others might need to watch fluids closely or avoid alcohol. And some may not be able to fly.

Written by American Heart Association editorial staff and reviewed by science and medicine advisors. See our editorial policies and staff .

Last Reviewed: Jan 16, 2024

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- What is a stroke? A Mayo Clinic expert explains

Learn more from neurologist Robert D. Brown, Jr. M.D., M.P.H.

I'm Dr. Robert Brown, neurologist at Mayo Clinic. In this video, we'll cover the basics of a stroke. What is it, who it happens to, the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Whether you're looking for answers for yourself or someone you love, we're here to give you the best information available. You've likely heard the term stroke before. They affect about 800,000 people in the United States each year. Strokes happen in two ways. In the first, a blocked artery can cut off blood to an area of the brain. And this is known as an ischemic stroke. 85% of strokes are of this type. The second type of stroke happens when a blood vessel can leak or burst. So the blood spills into the brain tissue or surrounding the brain. And this is called a hemorrhagic stroke. Prompt treatment can reduce brain damage and the likelihood of death or disability. So if you or someone you know is experiencing a stroke, you should call 911 and seek emergency medical care right away.

Anyone can have a stroke, but some things put you at higher risk. And some things can lower your risk. If you're 55 and older, if you're African-American, if you're a man, or if you have a family history of strokes or heart attacks, your chances of having a stroke are higher. Being overweight, physically inactive, drinking alcohol heavily, recreational drug use. Those who smoke, have high blood pressure or high cholesterol, have poorly controlled diabetes, suffer from obstructive sleep apnea, or have certain forms of heart disease are at greater risk as well.

Look for these signs and symptoms if you think you or someone you know is having a stroke: Sudden trouble speaking and understanding what others are saying. Paralysis or numbness of the face, arm or leg on one side of the body. Problems seeing in one or both eyes, trouble walking, and a loss of balance. Now many strokes are not associated with headache, but a sudden and severe headache can sometimes occur with some types of stroke. If you notice any of these, even if they come and go or disappear completely, seek emergency medical attention or call 911. Don't wait to see if symptoms stop, for every minute counts.

Once you get to the hospital, your emergency team will review your symptoms and complete a physical exam. They will use several tests to help them figure out what type of stroke you're having and determine the best treatment for the stroke. This could include a CT scan or MRI scan, which are pictures of the brain and arteries, a carotid ultrasound, which is a soundwave test of the carotid arteries which provide blood flow to the front parts of the brain, and blood tests.

Once your doctors can determine if you're having an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, they'll be able to figure out the best treatment. If you're suffering an ischemic stroke, it's important to restore blood flow to your brain as quickly as possible, providing the oxygen and other nutrients your brain cells need to survive. To do this, doctors may use an intravenous clot buster medicine, dissolving the clot that is obstructing the blood flow or they may perform an emergency endovascular procedure. This involves advancing a tiny plastic tube called a catheter up into the brain arteries, allowing the blockage in the artery to be removed directly. Unlike ischemic strokes, the goal for treating a hemorrhagic stroke is to control the bleeding and reduce pressure in the brain. Doctors may use emergency medicines to lower the blood pressure, prevent blood vessel spasms, encourage clotting and prevent seizures. Or, if the bleeding is severe, surgery may be performed to remove the blood that is in the brain.

Every stroke is different, and so every person's road to recovery is different. Management of a stroke often involves a care team with several specialties. This may include a neurologist and a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician, among others. Now, in the end, our goal is to help you recover as much function as possible so that you can live independently. A stroke is a life-changing event that can affect you emotionally as much as it can physically. You may feel helpless, frustrated, or depressed. So look for help and support from friends and family. Accept that recovery will take hard work and most of all time. Strive for a new normal and remember to celebrate your progress. If you'd like to learn even more about strokes, watch our other related videos or visit mayoclinic.org. We wish you all the best.

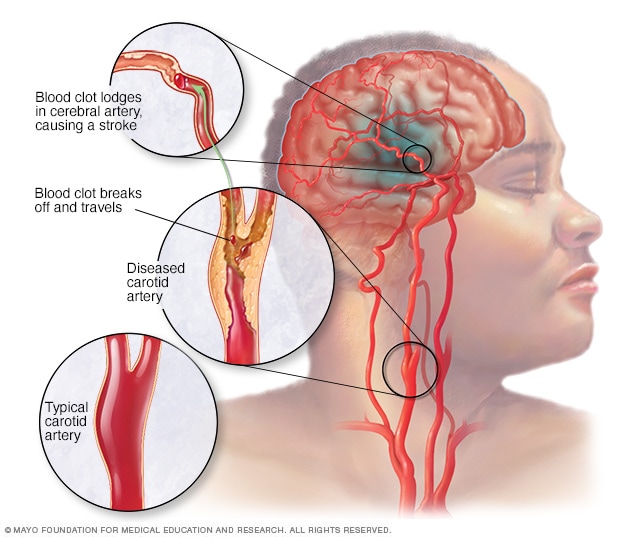

An ischemic stroke occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is blocked or reduced. This prevents brain tissue from getting oxygen and nutrients. Brain cells begin to die in minutes. Another type of stroke is a hemorrhagic stroke. It occurs when a blood vessel in the brain leaks or bursts and causes bleeding in the brain. The blood increases pressure on brain cells and damages them.

A stroke is a medical emergency. It's crucial to get medical treatment right away. Getting emergency medical help quickly can reduce brain damage and other stroke complications.

The good news is that fewer Americans die of stroke now than in the past. Effective treatments also can help prevent disability from stroke.

Products & Services

- A Book: Future Care

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

If you or someone you're with may be having a stroke, pay attention to the time the symptoms began. Some treatments are most effective when given soon after a stroke begins.

Symptoms of stroke include:

- Trouble speaking and understanding what others are saying. A person having a stroke may be confused, slur words or may not be able to understand speech.

- Numbness, weakness or paralysis in the face, arm or leg. This often affects just one side of the body. The person can try to raise both arms over the head. If one arm begins to fall, it may be a sign of a stroke. Also, one side of the mouth may droop when trying to smile.

- Problems seeing in one or both eyes. The person may suddenly have blurred or blackened vision in one or both eyes. Or the person may see double.

- Headache. A sudden, severe headache may be a symptom of a stroke. Vomiting, dizziness and a change in consciousness may occur with the headache.

- Trouble walking. Someone having a stroke may stumble or lose balance or coordination.

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical attention if you notice any symptoms of a stroke, even if they seem to come and go or they disappear completely. Think "FAST" and do the following:

- Face. Ask the person to smile. Does one side of the face droop?

- Arms. Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward? Or is one arm unable to rise?

- Speech. Ask the person to repeat a simple phrase. Is the person's speech slurred or different from usual?

- Time. If you see any of these signs, call 911 or emergency medical help right away.

Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Don't wait to see if symptoms stop. Every minute counts. The longer a stroke goes untreated, the greater the potential for brain damage and disability.

If you're with someone you suspect is having a stroke, watch the person carefully while waiting for emergency assistance.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

There are two main causes of stroke. An ischemic stroke is caused by a blocked artery in the brain. A hemorrhagic stroke is caused by leaking or bursting of a blood vessel in the brain. Some people may have only a temporary disruption of blood flow to the brain, known as a transient ischemic attack (TIA). A TIA doesn't cause lasting symptoms.

- Ischemic stroke

An ischemic stroke occurs when a blood clot, known as a thrombus, blocks or plugs an artery leading to the brain. A blood clot often forms in arteries damaged by a buildup of plaques, known as atherosclerosis. It can occur in the carotid artery of the neck as well as other arteries.

This is the most common type of stroke. It happens when the brain's blood vessels become narrowed or blocked. This causes reduced blood flow, known as ischemia. Blocked or narrowed blood vessels can be caused by fatty deposits that build up in blood vessels. Or they can be caused by blood clots or other debris that travel through the bloodstream, most often from the heart. An ischemic stroke occurs when fatty deposits, blood clots or other debris become lodged in the blood vessels in the brain.

Some early research shows that COVID-19 infection may increase the risk of ischemic stroke, but more study is needed.

Hemorrhagic stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke occurs when a blood vessel in the brain leaks or ruptures. Bleeding inside the brain, known as a brain hemorrhage, can result from many conditions that affect the blood vessels. Factors related to hemorrhagic stroke include:

- High blood pressure that's not under control.

- Overtreatment with blood thinners, also known as anticoagulants.

- Bulges at weak spots in the blood vessel walls, known as aneurysms.

- Head trauma, such as from a car accident.

- Protein deposits in blood vessel walls that lead to weakness in the vessel wall. This is known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- Ischemic stroke that leads to a brain hemorrhage.

A less common cause of bleeding in the brain is the rupture of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM). An AVM is an irregular tangle of thin-walled blood vessels.

Transient ischemic attack

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a temporary period of symptoms similar to those of a stroke. But a TIA doesn't cause permanent damage. A TIA is caused by a temporary decrease in blood supply to part of the brain. The decrease may last as little as five minutes. A transient ischemic attack is sometimes known as a ministroke.

A TIA occurs when a blood clot or fatty deposit reduces or blocks blood flow to part of the nervous system.

Seek emergency care even if you think you've had a TIA . It's not possible to tell if you're having a stroke or TIA based only on the symptoms. If you've had a TIA , it means you may have a partially blocked or narrowed artery leading to the brain. Having a TIA increases your risk of having a stroke later.

Risk factors

Many factors can increase the risk of stroke. Potentially treatable stroke risk factors include:

Lifestyle risk factors

- Being overweight or obese.

- Physical inactivity.

- Heavy or binge drinking.

- Use of illegal drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine.

Medical risk factors

- High blood pressure.

- Cigarette smoking or secondhand smoke exposure.

- High cholesterol.

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Cardiovascular disease, including heart failure, heart defects, heart infection or irregular heart rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation.

- Personal or family history of stroke, heart attack or transient ischemic attack.

- COVID-19 infection.

Other factors associated with a higher risk of stroke include:

- Age — People age 55 or older have a higher risk of stroke than do younger people.

- Race or ethnicity — African American and Hispanic people have a higher risk of stroke than do people of other races or ethnicities.

- Sex — Men have a higher risk of stroke than do women. Women are usually older when they have strokes, and they're more likely to die of strokes than are men.

- Hormones — Taking birth control pills or hormone therapies that include estrogen can increase risk.

Complications

A stroke can sometimes cause temporary or permanent disabilities. Complications depend on how long the brain lacks blood flow and which part is affected. Complications may include:

- Loss of muscle movement, known as paralysis. You may become paralyzed on one side of the body. Or you may lose control of certain muscles, such as those on one side of the face or one arm.

- Trouble talking or swallowing. A stroke might affect the muscles in the mouth and throat. This can make it hard to talk clearly, swallow or eat. You also may have trouble with language, including speaking or understanding speech, reading or writing.

- Memory loss or trouble thinking. Many people who have had strokes experience some memory loss. Others may have trouble thinking, reasoning, making judgments and understanding concepts.

- Emotional symptoms. People who have had strokes may have more trouble controlling their emotions. Or they may develop depression.

- Pain. Pain, numbness or other feelings may occur in the parts of the body affected by stroke. If a stroke causes you to lose feeling in the left arm, you may develop a tingling sensation in that arm.

- Changes in behavior and self-care. People who have had strokes may become more withdrawn. They also may need help with grooming and daily chores.

You can take steps to prevent a stroke. It's important to know your stroke risk factors and follow the advice of your healthcare professional about healthy lifestyle strategies. If you've had a stroke, these measures might help prevent another stroke. If you have had a transient ischemic attack (TIA), these steps can help lower your risk of a stroke. The follow-up care you receive in the hospital and afterward also may play a role.

Many stroke prevention strategies are the same as strategies to prevent heart disease. In general, healthy lifestyle recommendations include:

- Control high blood pressure, known as hypertension. This is one of the most important things you can do to reduce your stroke risk. If you've had a stroke, lowering your blood pressure can help prevent a TIA or stroke in the future. Healthy lifestyle changes and medicines often are used to treat high blood pressure.

- Lower the amount of cholesterol and saturated fat in your diet. Eating less cholesterol and fat, especially saturated fats and trans fats, may reduce buildup in the arteries. If you can't control your cholesterol through dietary changes alone, you may need a cholesterol-lowering medicine.

- Quit tobacco use. Smoking raises the risk of stroke for smokers and nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke. Quitting lowers your risk of stroke.

- Manage diabetes. Diet, exercise and losing weight can help you keep your blood sugar in a healthy range. If lifestyle factors aren't enough to control blood sugar, you may be prescribed diabetes medicine.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Being overweight contributes to other stroke risk factors, such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

- Eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables. Eating five or more servings of fruits or vegetables every day may reduce the risk of stroke. The Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes olive oil, fruit, nuts, vegetables and whole grains, may be helpful.

- Exercise regularly. Aerobic exercise reduces the risk of stroke in many ways. Exercise can lower blood pressure, increase the levels of good cholesterol, and improve the overall health of the blood vessels and heart. It also helps you lose weight, control diabetes and reduce stress. Gradually work up to at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity on most or all days of the week. The American Heart association recommends getting 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity a week. Moderate intensity activities can include walking, jogging, swimming and bicycling.

- Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all. Drinking large amounts of alcohol increases the risk of high blood pressure, ischemic strokes and hemorrhagic strokes. Alcohol also may interact with other medicines you're taking. However, drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol may help prevent ischemic stroke and decrease the blood's clotting tendency. A small to moderate amount is about one drink a day. Talk to your healthcare professional about what's appropriate for you.

- Treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OSA is a sleep disorder that causes you to stop breathing for short periods several times during sleep. Your healthcare professional may recommend a sleep study if you have symptoms of OSA . Treatment includes a device that delivers positive airway pressure through a mask to keep the airway open while you sleep.