An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Developing ecotourism sustainability maximization (ESM) model: a safe minimum standard for climate change mitigation in the Indian Himalayas

Smriti ashok.

1 Faculty, Department of Architecture and Planning, National Institute of Technology Patna, Ashok Rajpath, Mahendru, Patna, Bihar 800005 India

Mukund Dev Behera

2 Centre for Oceans, Rivers, Atmosphere and Land Sciences (CORAL), Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, West Bengal 721302 India

Hare Ram Tewari

3 Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, West Bengal 721302 India

Chinmoy Jana

4 Indian Institute of Social Welfare and Business Management (IISWBM), College Square (W), Kolkata, 700073 India

Associated Data

Recently, ecotourism has been identified as an adaptation strategy for mitigating climate change impacts, as it can optimize carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery, and livelihood benefits and generate new opportunities for the sustenance of the economy, environment, and society of the area endowed with natural resources and cultural values. With the growing responsibility at the global level, ecotourism resource management (ERM) becomes inevitable for its sustainable requirements. The integration of ecological and socio-economic factors is vital for ERM, as has been demonstrated by developing an Ecotourism Sustainability Maximization Model for an area under study, that is the Yuksam-Dzongri corridor (also known as Kangchendzonga Base Camp Trek), in the Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve (KBR), Sikkim, India. This model is based on the earlier developed ecotourism sustainability assessment (ESA) framework by the authors, which is based on the hierarchical relationship among ecotourism principles, criteria, indicators, and verifiers. Employing such relationships, this paper attempts to maximize ecotourism sustainability (ES) as a function of its sustainability principles, criteria, indicators, and verifiers, subject to the constraints identified through the safe minimum standard (SMS) approach by employing linear programming. Using 58 indicators as decision variables and 114 constraints, the model resulted in a maximum level of achievable ES with a score of 84.6%, allowing the resultant optimum values of the indicators to be maintained at the operational level. A central tenet of the model is the collective responsibility and adoption of a holistic approach involving the government, tourists, tourism enterprises, and local people.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10661-022-10548-0.

Introduction

Biodiversity and conservation of cultural diversity through ecotourism is a viable tool to meet the objectives of the convention on biological diversity (CBD, 1992 , 2018 ; UNDESA, 2021 ; UNEP, 2002 ). Ecotourism as a part of sustainable tourism is firmly positioned in the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With the potential to contribute, directly or indirectly, to all the 17 SDGs, ecotourism has been included as a target in goals #8, #12, and #14 (WTO-UNDP, 2017 ). Ecotourism can be a prominent factor in achieving the targets of SDG 13–Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impact due to its ability to produce new opportunities for the economy, environment, and society of the area endowed with natural and cultural resources. This has been proved in some areas where ecotourism is accepted as an adaptation strategy for mitigating the impacts of climate change on local communities, such as around the protected areas in Ghana, the Dana Biosphere Reserve, Jordan, etc. (Jamaliah & Powell, 2018 ; Agyeman, 2019 ). Ecotourism holds a 7% share of the international tourism market of 903 million tourist arrivals and tourist receipts of US$856 billion suggests a 2007 estimate by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). “Tourism Towards 2030,” UNWTO’s ( 2011 , 2015 ) long-term outlook and an assessment with quantitative projections estimate that with an average annual growth until 2030, international tourist arrivals worldwide are expected to grow to 1.8 billion, indicating the likely worth of ecotourism.

Ecotourism is a major income-generating ecosystem service which adds to both biomass accumulation and biodiversity recovery to mitigate the global climate change impact. Biomass accumulation results in a net increase in standing biomass in forest areas and attracts more ecotourists (Di Sacco et al., 2020 ). A study by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity – TEEB ( 2009 ) initiative estimated the value of tropical forest ecosystem services to be USD 6120/ha/year, based on data from 109 studies, where recreation and tourism contributed 6.2%. Through this role, ecotourism can provide alternative sources of livelihood opportunities and support the locals to meet the challenges posed by climate change. Thus, it is extremely effective for sustainable development, yet, over the years many adverse impacts of ecotourism have been observed in the form of trail proliferation and widening, vegetation-cover loss, exposed tree roots, soil erosion, littering at recreation sites, water contamination, unsightly, and dangerous construction, the occurrence of landslides, degradation of trekking routes, climate change-induced fires, etc. (Sirakaya et al., 2001 ; Newsome et al., 2002 ; Page & Dowling, 2002 ; Jiang, 2009 ; NITI Aayog, 2018 ).

To conserve the environmental resources, these red signals should be continually monitored to identify any negative environmental impact and corrective measures can be taken to restore the balance (Ashok et al., 2017 ; Eraqi, 2007 ; Popova, 2003 ). In this regard, ecotourism needs to be made sustainable itself through the Sustainability Monitoring Methodology, so that it can take care of environmental and cultural resources and contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions; educating communities, tourism stakeholders, and tourists on how to prepare for and adapt to climate change and protect the environment. We have identified–BellagioSTAMP-2009, developed by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) as a guide to the Societies’ initiative toward measuring the progress of sustainable development based on its eight principles for sustainability assessment and measurement (IISD, 2009 ). Among its eight principles, the “Framework and Indicators of Sustainability Assessment” describes that for developing a sustainability assessment procedure, the following four steps are required–(i) a conceptual framework that identifies the domains within which core indicators to assess progress are to be identified, (ii) standardized measurement methods wherever possible, in the interest of comparability, (iii) step 3 – the most recent and reliable data, projections, and models to infer trends and build scenarios, and (iv) step 4 – comparison of indicator values with targets, as possible (IISD, 2009 ; Pinter et al., 2012 ).

Realizing the effectiveness of the BellagioSTAMP-2009 guidelines and being cognizant of the fact that there is no scientific method for ecotourism sustainability, the authors are in the process of developing a comprehensive methodology for the assessment of ecotourism’s sustainability namely, “Ecotourism Sustainability Assessment Method–ESAM” through a series of studies, namely–Stage 1, Stage 2, Stage 3, and Stage 4. As duly discussed below, the first two stages have already been developed, while work is in progress for the last two. Stage 1 gave the “conceptual framework,” i.e., the development of the ecotourism sustainability assessment (ESA) framework–a set of principles, criteria, indicators, and verifiers to guide the measurement of the progress of the ecotourism sustainability (ES) (Ashok et al., 2017 ). Wherein, stage 2 offered a “standardized method” mentioned as–the development of the Ecotourism Sustainability Maximization (ESM) model , to set the target for achieving the maximum level of ES, which is the main objective of this paper.

The objectives are as follows: (a) to understand the impact of the global shutdown on tourists’ arrivals during COVID-19, (b) to determine the decision variables (DVs) for operationalizing the ecotourism sustainability principles at the destination level, based on the identified linear relationship among the principles, criteria, and indicators–verifiers of the already developed ESA framework, (c) to maximize the sustainability of the ecotourism destinations, despite their ecological and social constraints impeding the achievement of ecotourism sustainability, (d) to estimate the optimum value of the decision variables, i.e., ESIs for defining the use level of the resources at the ecotourism destinations, and (e) to understand the application of the optimum value of the decision variables obtained through the ESM model for the sustainability of the ecotourism destination.

The study site chosen is “Yuksam-Dzongri Corridor of West District of Sikkim Himalaya, India” with the intent to validate each step of the ESAM methodology–to obtain the necessary data on verifiable evidence, obtained through scientific data collection and periodic observation methods. The development of the ESM model is not mere empirical research, it has a strong scientific, mathematical, and theoretical base in the form of the well-established safe minimum standard approach, ecological constraints, linear equations, C&I approach, and BellagioSTAMP, etc. (Ciriacy-Wantrup, 1952 ; Perring, 1991 ; Colfer et al., 1995 ; Wright et al., 2002 ; IISD, 2009 ; Pinter et al., 2012 ).

ESM model–concepts

Ecotourism resource management (erm).

Ecotourism resource management (ERM) aims at the efficient management of ecotourism resources . It consists of natural (geographical position, microclimatic conditions, the existence of wildlife, vegetation, natural beauty, geo-morphologic structure, etc.) and cultural resources (local people, dress, food, dance/music events, festivals, architectural heritage, etc.) which collectively attract tourists from all over the world (Boley & Green, 2016 ; Eraqi, 2007 ; Kiper, 2013 ). Thus, it requires limiting the use–level of ecotourism resources, which can be managed through the safe minimum standard (SMS) approach, proposed by many scholars to help achieve the goal of sustainable ecotourism development (Perring, 1991 ; Pigram, 1990 ).

Safe minimum standard approach

The term “SMS” was first coined by Ciriacy-Wantrup ( 1952 ) for the conservation of renewable resources. This approach is defined as a collective choice process that prescribes protecting a minimum level or safe standard of a renewable natural resource unless the social costs of doing so are somehow excessive or intolerably high (Berrens et al., 1998 ). It is a “socially determined dividing line between moral imperatives to preserve and enhance natural resource systems and the free play of resource trade-off” (Toman, 1994 ; Munasinghe & Shearer, 1995 ). The SMS is a policy that eliminates the risk of catastrophic outcomes in the management of natural resources and can be used to develop the “Ecological Sustainability Constraints.” These constraints can impose direct restrictions on resources–using economic activities by deciding the level of environmental resources’ use within a limit, to achieve sustainability in the field of tourism development (Perring, 1991 ; Pigram, 1990 ).

Application of ERM and SMS through the ESA framework

The concepts of ERM and SMS can be applied to an ecotourism destination through some framework to help establish a symbiotic relationship among people, natural resources or biodiversity, and tourism activities and help to make it sustainable. In this regard, the “C&I approach”–which is used as an abbreviation for the entire hierarchy of principles, criteria, indicators, and verifiers (PCIV), has been applied. This offers a structured approach toward defining the means and objectives of achieving sustainability of ecology, economy, and society and calculating the progress of sustainability at the destination level (Colfer et al., 1995 ; Wright et al., 2002 ). Here, the ESA framework can help implement the above goals, as it has been developed using the C&I approach, as discussed below.

Structure of the ESA framework

The ESA framework has been developed using the C&I (PCIV) approach, which provides the theoretical basis for the development of the present ESM model. It states that ES depends upon its four fundamental principles–Sp I to Sp IV. These ecotourism sustainability principles are dependent on 8 ecotourism sustainability criteria– C 1 to C 8 , which further have a dependence upon 58 ecotourism sustainability indicators (ESIs)– X 11 to X 58 and their corresponding 58–verifies. The 58–verifiers can provide the status of their corresponding ESIs by collecting field-level information (as mentioned in Table Table1) 1 ) (Ashok et al., 2017 ; Kumari, 2008 ; Kumari et al., 2005 ). This framework can be a powerful tool for sustainable ecotourism development and management, provided it computes the optimum values of ESIs using a “Resource Optimization Model.”

Nomenclature used for the Principles, Criteria, Indicators, and Verifiers, developed under the Ecotourism Sustainability Assessment (ESA) Framework, and calculated weights and Ecotourism sustainability constraints for ESIs (DV-Decision Variable)

ARW average relative weight (average relative weight calculated for Indicators, obtained from the subject (Ecotourism) experts and ecotourism key stakeholders), AAV average acceptable value (acceptable value of indicators obtained from ecotourism key stakeholders), ADV average desirable value (desirable value of indicators obtained from ecotourism key stakeholders)

Resource optimization model through stakeholders’ participation and application of linear programming

ERM necessitates the decision of the optimal management of environmental and socio-cultural resources to restrict their use level and guide ecotourism on the path of sustainability. Ecologically constrained optimization models have been developed by Walter and Schofield ( 1977 ) and Bertuglia et al. ( 1980 ) for the optimal management of wilderness recreation resources. However, these optimization models have not used any serious moral and social discourse while deciding on the use of environmental resources within a limit, which can provide the solution to the issue of “where to stop?” in ecotourism development.

To fulfill this, the stakeholders’ participation approach was adopted to define the use level of ecotourism resources in the study area, in the form of acceptable and desirable values of indicators for ES. The “acceptable value” of indicators refers to the acceptable levels of use of resources, which are primarily a matter of judgment (scientific or societal) based on reproductive rates, habitat conditions, market demand, and so forth (Munasinghe & Shearer, 1995 ). While the essence of “desirable value” refers to maintaining desirable conditions over time to attain intergenerational equity, which should be reflected in the system’s long To fulfill this, the stakeholders’ participation approach was adopted to define the use level of ecotourism resources in the study area, in the form of acceptable and desirable values of indicators for ES. The “acceptable value” of indicators refers to the acceptable levels of use of resources, which are primarily a matter of judgment (scientific or societal) based on reproductive rates, habitat conditions, market demand, and so forth (Munasinghe & Shearer, 1995 ). While the essence of “desirable value” refers to maintaining desirable conditions over time to attain intergenerational equity, which should be reflected in the system’s long-term stability (Prabhu et al., 1999 ). These location-specific inputs (which may also differ at different time intervals) can be used as lower and upper limit values of decision variables while formulating the linear equation. As linear programming can provide an optimal solution for a real-life problem with given constraints. It facilitates optimal allocation of resources by minimizing (e.g,. maybe overall cost of production, the adverse impact on environment, etc.) or maximizing (e.g., maybe level of sustainability of environment, customer satisfaction) its overall goal to find the solution to a problem. Thus, it can provide a simultaneous solution to three basic problems of the economy, i.e., (a) optimum allocation of productive resources, (b) efficient utilization of these resources, and (c) realizing a balance between the different sectors of the economy to generate maximum benefit (Bertuglia et al., 1980 ; Overton, 1997 ; Walter & Schofield, 1977 ). Here, this method has been applied to maximize “ecotourism-sustainability” to defining the “use level of ecotourism resources” at the optimum level under several practical constraints.

Study area description

The study area is the Yuksam-Dzongri Corridor, KBR, near the Rathong Glacier (4380 m) of the Himalayan mountain region in India (Fig. (Fig.1). 1 ). The tourists data showed a rise in ecotourism over 5 times, from 1964 tourists in 1990–1991 to 10490 visitors in 2009–2010. It also showed a decline in tourist arrivals during 2011–2013 due to the earthquake in the KBR in September 2011 (Bhardwaj, 2011 ; HMI, 2018 ). Tourist arrivals further increased to 9951 during 2019 before dropping to an almost negligible level due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. (Fig.2 2 ).

Location map of the study area showing West District of Sikkim. Some points of tourist attractions along the trekking route are overlaid on satellite image of Kangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve

Sharp decline in Tourists Arrival can be seen in 2020, coinciding with Covid-19. However, Regression based extrapolation up to 2030 predicts a fast reversal–trend and forecast after COVID-19. Data Source: 1990–2006 (Tambe et al., 2011 ), 2008–2019 (KNP-RO (Kangchendzonga National Park, Range Office), 2019 ), Yuksam, West District, Sikkim

Methodology

Influence of covid-19 on ecotourism.

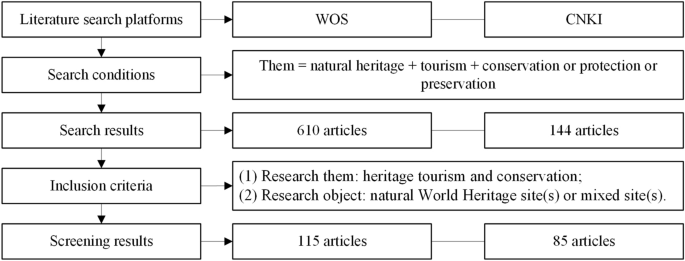

To assess the influence of COVID-19 on ecotourism at the destination and forecast the possible recovery from the terrible situation, the trend equation using the regression method was applied to the tourists’ arrival data up to 2019 and to the pandemic-impacted data of 2020. Depending on various other factors, the number of tourists is expected to rise by 2024–2026 ( S1 ; Fig. Fig.2). 2 ). The projection was done in two stages.

Estimation of tourists’ arrival

This stage derived inspiration from two studies: (1) a global survey by the UNWTO’s panel of tourism experts on international tourist arrivals in different geographies across the globe (UNWTO, 2021 ), and (2) a comprehensive study conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), India upon the impact of COVID-19 on Indian household income and tourism recovery (NCAER, 2021 ). We devised two scenarios for the estimation of recovery of tourism using the Delphi method. It is an iterative and consensus-building approach to soliciting opinion and judgment by a group of experts on a particular topic and a much-used method in multiple studies related to tourism recovery forecasts (Zhang et al., 2021 ).

- #1. Scenario 1–recovery “up to 2024”

- #2. Scenario 2–recovery “later than 2024”

After completing the first and second rounds of the Delphi survey, 5-point scores were given by the experts for calculating the final values. The second estimation was based on a mix of the experts’ viewpoints (UNWTO, 2021 ) followed by the experts’ opinion pooling in two Delphi rounds.

Forecasting of the tourist arrival based on trend equation using regression

Based on the above estimation of tourist arrivals from 2020 to 2026, further 4 scenarios (S-1, S-2, S-3, and S-4) of forecasting tourist arrivals have been done by applying trend equation using regression analysis in IBM SPSS (statistical package for social scientists), 20.0. Scenarios S-1 and S-2 are based on estimated tourist data, and scenarios S-3 and S-4 are based on the percentage of estimated tourist data (Figs. (Figs.2; 2 ; S1 ).

Development of the ESM model

Considering a linear relationship among the principles, criteria, and indicators, the linear programming (LP) model was applied to develop a decision-making structure to maximize the ES as a function of ecotourism principles, criteria, indicators, and corresponding verifiers. To model a linear problem, first, the decision variables were established. Here, the DVs have been determined from the ESA framework. ecotourism sustainability (ES) depends on 58 ecotourism sustainability indicators (ESIs) and their corresponding verifiers at the operational level. These 58 ESIs are considered DVs of the model (Ashok et al., 2017 ). The relative weights for the ESIs (decision variables) were obtained by implying both the Top-Down and Bottom-up approaches through the participation of subject matter (Ecotourism) experts and local key stakeholders in two stages.

Relative weight using top-down and bottom-up approach

The top-down approach refers to the application of the Delphi technique, where 19 subject matter experts ( n = 14 for 2003–2004; n = 5 for 2013) of multi-disciplinary backgrounds participated in allotting relative weights (between 0 and 100) to the sustainability principles of ecotourism (Sp I to Sp IV ). These values were calculated and their mean values were accepted. Further, all the criteria related to each principle received a pro-rated weight of that particular principle based on the priority ranking given to them by the experts. Then, their mean values were accepted as relative weight factors for criteria (Fig. (Fig.3 3 ).

Broad outline for development of ecotourism sustainability assessment (ESA) Framework and Ecotourism Sustainability Maximization (ESM) Model

The bottom-up approach refers to the participation of local key stakeholders ( n = 10 for 2003–2004; n = 4 for 2018–2019) in allotting the priority ranking to the indicators (ESIs- X 11 to X 86 ) to operationalize their receptive criteria. Secondly, the weight for each criterion obtained in Stage I is assumed as 100 and then is distributed among the related indicators depending upon their priority ranking given by the local experts. Subsequently, the weights calculated for individual indicators are multiplied by the final weight factor of their respective criterion to obtain the relative efficacy of a particular indicator ( S 2 ). Finally, the relative weights for indicators (ESIs) are calculated and mean values are accepted for the model (Table (Table1; 1 ; Fig. Fig.4 4 ).

Methodology adopted for the development of the Ecotourism Sustainability Maximization Model

Developing linear equations for the model

The ESA framework entails that ES is based on its four key principles, i.e., (i) protection of natural and cultural resources ( Sp I ), (ii) generation of socio-economic benefits to the local community ( Sp II ), (iii) generation of environmental awareness ( Sp III ), and (iv) optimum satisfaction of touristic aspirations ( Sp IV ). These four principles have been operationalized through the different combinations of criteria like Sp I by C 1 , C 2 , C 4 , C 6 , and C 8 ; Sp II by C 1 and C 4 ; Sp III through C 4 and C 7 ; and Sp IV through C 1 , C 5 , C 7, and C 8 . These criteria can be operationalized through their respective indicators (Ashok et al., 2017 ; Kumari et al., 2005 ). Based on the relationship between the components of the ESA framework, the equation was formulated to define the objective function of the model. Ecotourism Sustainability (ES) is dependent upon 4 principles, which can be formulated as:

- W i = Weight for the i th principle of ecotourism sustainability

- Sp i = Ecotourism principles

Subsequently, the 4-principles ( Sp I , Sp IV ) depend upon the 8-criterion ( C 1 , C 8 ) occurring in different combinations for each of the principles. This is formulated as:

where W ij = Weight of j th criteria for i th principle.

Using Eqs. ( 2 ), ( 3 ), ( 4 ), and ( 5 ) in Eq. ( 1 ) where weight allocated for C 1 to C 8 can be combined ( S2 ), it can be presented as:

The 8 criteria ( C 1 , C 8 ) depend upon their respective indicators ( X 11 , X 86 ) (ESA framework; Ashok et al., 2017 ). This can be formulated as:

- X ij means j th indicator for i th criteria

- w ′ ij means weight for X ij

Formulation of the objective function

In the present model, the maximization of ecotourism sustainability has been defined as the objective function. ES depends upon four principles, namely, Sp I and Sp IV (Eq. ( 1 )). These four principles depend upon many criteria (Eqs. ( 2 ), ( 3 ), ( 4 ), and ( 5 )). Further, these criteria depend upon several indicators (Eqs. ( 7 ), ( 8 ), ( 9 ), ( 10 ), ( 11 ), ( 12 ), ( 13 ), and ( 14 )). Finally, ES depends upon 58 indicators, considered as the DVs for the model. Among the 58-DVs, 13 have a negative impact on the sustainability of ecotourism but the remaining ones have a positive impact. As maximization of ecotourism sustainability is the objective of the model, the following equation was formulated to obtain the OV of indicators (Eq. ( 15 )).

Development of ecotourism constraints and sustainability indicators

58 bounded constraints were based on the desirable and acceptable values of the DVs (Table (Table1), 1 ), while 56 others were identified based on the dependence of each variable on others (Table (Table2). 2 ). The acceptable and desirable values obtained by consulting local experts were used as bounded constraints (Table (Table1). 1 ). These values were used as lower and upper bounds in the model, respectively.

Other constraints developed by identifying the dependency of each Ecotourism Sustainability Indicator (Decision Variables)

In the case of decision variables having a positive impact

where m ij = the minimum value of the decision variable required for ecotourism sustainability, X ij = decision variable, and M ij = maximum value of decision variable are desirable for ecotourism sustainability.

For example, for the indicator X 11 = 22% ≤ X 11 ≤ 40.5%.

In the case of decision variables having a negative impact.

The negative impact of DVs indicates that when these DVs increase, the ecotourism sustainability will decrease, therefore,

where m ij = the minimum value of decision variable desirable for ecotourism sustainability, X ij = decision variable, and M ij = maximum value of decision variable acceptable for ecotourism sustainability.

For example, for indicator X 16 the acceptable and desirable values may be presented as 9.80% ≤ X 16 ≤ 4.90%. The growth of exotic plants is very harmful to the indigenous plant communities because the alien plants compete with them for space, light, nutrients, and water (Newsome et al., 2002 ). So, less than 4.90% growth of weeds is desirable for the ES, while up to 9.80% of the growth of weeds (from the base year of 1995) is acceptable for the study area. The key stakeholders have allotted acceptable and desirable values for each DV. Their mean values were calculated and have been accepted for the model as constraints (lower and upper bounds for decision variables) in the model (Table (Table1 1 ).

Other constraints

The dependency of each indicator was identified on other indicators, and respective weights were assigned. For example, wildlife sighting depends on the availability of clean water ( X 13 ) and the abundance of forest resources ( X 14 ). The abundance of these resources depends upon the involvement of the younger generation in the conservation of natural resources ( X 86 ), which requires the transfer of traditional resource conservation knowledge to the younger generation ( X 85 ). This is only possible when the local population is aware ( X 71 ) and empowered ( X 81 ) to protect resources. Along with this, it also requires government regulatory policy regarding the protection of natural resources ( X 41 ). Such dependency has been taken as the basis of the following equation.

The above equation indicates the dependency of decision variable X 11 on the other variables, namely, X 13 , X 14 , X 41 , X 71 , X 81 , X 85 , and X 86 . It also means that the value of X 11 should be less than the sum of individual weights of the above 7 which are 0.09, 0.09, 0.14, 0.18, 0.16, 0.22, and 0.12, respectively. Similarly, the dependency of each indicator was identified and assigned their respective weights. These equations were used as constraints in the model (Table (Table2 2 ).

The objective function was solved for 58 DVs in total, subject to a set of 114 constraints, by using the traditional simplex method for single objective linear programming with the help of the QSB software (Jana et al., 2004 ) through the Eq. ( 15 ).

Results and discussions

Trend equation regression analysis generated four scenarios for the recovery of tourist arrivals, namely, S-1, S-2, S-3, and S-4, in the study area. These scenarios estimated the recovery period (for tourists’ arrival) of 4 years, 4–5 years, 6 years, and 5–6 years, respectively to reach the level of 2019. Among these four scenarios, the best forecasting has been shown in scenario 2, where the mean square error is minimal, i.e., 234.82 and estimates the recovery by 2026, increasing the tourists’ number up to 10,040 by then and eventually to 15,940 by 2030 (Fig. (Fig.2; 2 ; S1 ). The prediction curve shows a sharp decline in tourist arrivals in 2020 due to the situation created by COVID-19. However, regression-based extrapolation has shown a fast recovery in tourist arrivals by 2026, as the prediction is based on the actual tourists’ data from 2001 to 2019. This is reflected in the linear trend from “2001 to 2010” and “2012 to 2019” (Fig. (Fig.2). 2 ). The sharp decline in tourist arrival in 2011 and 2020 due to the occurrence of the 2011 earthquake in the area and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) proved that any kind of excessive use or abuse of “ecotourism resources” or a “dreadful pandemic” like situation may not only limit the potential tourism earnings in this area but also in the entire state of Sikkim in future (Singh & Bhutia, 2020 ). Moreover, the Yuksam-Dzongri trekking corridor falls under the alpine and sub-alpine vegetation zone of the Indian Himalayas, which needs utmost care to protect its sensitive biodiversity and possibly mitigate any probable adverse impact of climate change. In such a situation, the optimum value of decision variables (ESIs) obtained by the ESM model can act as a protective cover for controlling the use levels of ecotourism resources, thus maximizing the site’s sustainability afterward, if adopted.

With 58 indicators and 114 constraints (Eq. ( 15 )), the ESM model revealed the maximum level of ecotourism sustainability at a score of 84.6%. This value was further cross-checked on the barometer of sustainability/measure of success (BoS/MoS) scale (Table (Table3). 3 ). Based on the BOS scale, it can be construed that if an ecotourism destination achieves 80–100% (level 5) sustainability, it can be deemed to be a sustainable ecotourism destination. Further, the model derived the optimum value of the ecotourism sustainability indicators–ESIs (Table (Table4), 4 ), which means that the above level of ecotourism sustainability (84.6%) can only be achieved if the destination restricts the utility level of the environmental resources up to its optima.

Ecotourism sustainability performance scale

Optimum values of Decision Variable (ESIs) achieved from modeling using linear programming; 84.6% level of eco-tourism sustainability was achieved through the model

DV represents decision variables, OV represents optimum, ESIs represent ecotourism sustainability indicators

Now the question occurs that how the model derived “optimum values” of ecotourism sustainability indicators can help achieve sustainable ecotourism development? How it can manage the ecotourism resources so that specific types of natural and cultural attractions of the ecotourism destinations are maintained? In this regard, the authors identified three ways that can be useful for the authorities or ecotourism-site managers (i.e., in the case of Study Area the Forests and Environment Department; Tourism Department; Police Check-Post, Yuksam, as well as the CBO namely–Kangchendzonga Conservation Committee) can maintain the destination’s ecological sensitivity while sustainably managing ecotourism, as discussed below.

Relative contributions of criteria to achieve ecotourism sustainability

While scrutinizing the relative contributions of criteria in achieving 84.6% of ES, the contributions of “ C 1 ”– “maintenance of ecosystem health,” “ C 4 ”– “enabling environment and environmental awareness generation” and “ C 7 ”– “people’s participation” are a prerequisite for sustainable management and were found to be the maximum. This suggests that other criteria must support the fulfillment of the above criteria, but it does not undermine the importance of others. The next–highest contributions are of “ C 2 ” and “ C 8 ” which refer to preserving cultural diversity through the maintenance of the local culture and the use of indigenous ecological knowledge for ecotourism development and management. If the above-mentioned five criteria are supported by the adoption of carrying capacity “ C 6 ” norms, then it can provide an excellent base for the last two criteria, “ C 3 ”– “livelihood generation” and “ C 5 ”– “visitor satisfaction” ( S3 ).

Operationalisation of ecotourism sustainability principles through criteria and indicators

The first principle of ecotourism– “protection of natural and cultural resources,” Sp I , offers a challenge to ecotourism to develop its tourism capacity and the quality of its products without affecting the very environment that maintains and nurtures it. This requires the adoption of resource conservation values during the decision-making, which is possible by adopting the OV of indicators as guidelines. The contribution of “ C 1 ” “maintenance of ecosystem health,” towards achieving a sustainability score on the BoS/MoS scale was found the highest so it should be accorded the highest priority during any ecotourism development and management decision-making. This criterion is followed by “ C 2 ”– “maintenance of local culture,” “ C 6 ”– “carrying capacity,” “ C 4 ”– “enabling environment and environmental awareness generation,” “ C 7 ”– “people’s participation” and “ C 8 ”– “conservation management using traditional knowledge” ( S3 ).

While assessing the OV of ESIs (Table (Table4; 4 ; Fig. Fig.5a–h), 5 a–h), it can be construed that the optimum value of some indicators, viz. X 13 , X 14 , X 1 5 , X 16 , X 1 7 , X 1 8 , X 19 , X 111 , X 21 , X 23 , X 26 , X 27 , X 42 , X 43 , X 44 , X 63 , X 64 , X 72 , and X 85 are falling under the range of 80–100%. Next to these, are some indicators, viz. X 12 , X 110 , X 22 , X 24 , X 45 , X 46 , X 61 , X 62 , X 65 , X 71 , X 75 , X 84 , and X 86 have OV between 60–80%. These are followed by indicators X 11 , X 25 , X 41 , X 73 , X 74 , and X 76 having 40 to 60%. Lastly, values of a few indicators viz. X 48 , X 81 , and X 82 fall between 20–40%. In line with the guideline provided by the Quebec declaration on ecotourism (QDE, 2002 ) the OV of indicators emphasizes prioritizing critical components, as these are vital for maintaining the flow of ecosystem services. The relative contribution of criteria as per the ESA Framework and the relative contribution of ESIs as per the optimum value achieved by the ESM model can guide the ecotourism management authority.

a – h Optimum value achieved for 58 indicators with eight criteria; a. Maintenance of ecosystem health. b Maintenance of local culture. c Livelihood generation. d Enabling environment and environmental condition. e Tourists’ satisfaction. f Carrying capacity. g People’s participation. h Conservation management through indigenous knowledge

Likewise, principle I, the relative contribution of criteria as per the ESA framework and the relative contribution of ESIs as per Optimum Value achieved by the ESM model, has been analyzed for principles II, III, and IV for operationalizing the ecotourism sustainability principle in the study area mentioned in the supplementary document ( S 4 ). This can guide the ecotourism management authority to implement the optimum value of ESIs to restrict the use level of ecotourism resources in the area.

Application of optimum value of ESIs to restrict the utility level of ecotourism resources

The ecotourism management authority or site-managers can manage their destination’s valuable and sensitive resources for ecotourism based on the optimum value achieved by the model.

Supporting indicators for criterion C 1 (maintenance of healthy ecosystems)

Ecotourism management authorities or site managers need to restrict the use level of resources depending on the positive and negative impact of ESIs on the ES. Criterion, C 1 was objectively measured by examining its related indicators based on its OV resulting from the model (Fig. (Fig.5a; 5 a; Table Table4). 4 ). In the case of “availability of fresh water (rivers, streams, lakes)” ( X 13 ), the OV obtained was 96.5%. Hence the mountain ecosystem can be designated as healthy if pure water is abundantly available throughout the year. If 100% of the “religious and heritage sites” ( X 14 ), then it is presumed that the rich biodiversity and culture of the mountain ecosystem could be preserved. As the presence of ecosystem-specific plants, which represent the “unique ecosystem features (endemic species: floral and faunal)” ( X 15 ), are critical for the maintenance of the mountain ecosystem, their extent of occurrence should optimally be 98%. In the case of the “occurrence of the endangered/threatened species” ( X 18 ), the OV arrived was 96.5%, which calls for more conservation efforts from the part of forest department without which many species might become extinct and disturb the balance of the ecosystem. In the case of the composite indicator “status of civic amenities” ( X 110 ), the OV was 76%, which implies that even if only 76% of the population has access to safe drinking water and sanitation facilities and 76% of solid waste generated is disposed of, then the destination can also be considered sustainable (Table (Table4; 4 ; Fig. Fig.4 4 ).

In the case of negative indicators, i.e., “presence of exotic species (flora and fauna)” ( X 16 ), the OV derived was 4.9%, while for “growth in livestock population” ( X 17 ), the value obtained was 7%. This entails that beyond this level, any growth in weeds and livestock population may prove devastating for the region (Chettri et al., 2002 ). The OV for “RCC use in tourism infrastructure development” ( X 19 ) was derived as 5.2%, which depicts that beyond this level, RCC construction can have harmful effects on ecological health. This has been experienced in many destinations (Hunter & Green, 1995 ). “Occurrence of natural hazards” ( X 111 ), creates great imbalances in the functioning of the ecosystem and destructs the human life support system as well. Its value has also come close to the minimum desirable of 4.5% (Table (Table4; 4 ; Fig. Fig.5a). 5 a). The optimal values of indicators obtained by the model are of great importance.

Likewise, the optimal values of indicators obtained by the model are of great importance and are presented in Table Table4 4 and Fig. Fig.5b, 5 b, c, d, e, f, g, and h. If applied, they can help in achieving the maximum level of ecotourism sustainability at the operational level.

Under complex situations, having a multitude of interests among the stakeholders, i.e., tourists, locals, NGOs, tour operators, etc., the ESM model can prove to be an ideal solution as it adopts the SMS approach to define the acceptable and desirable values of indicators, referred to as, DVs by involving all stakeholders. Here, the ESM model can be considered an executable decision-making tool as it calculates the optimum value of 58 DVs to achieve 84.6% of ES, which falls under the Sustainable Category (80–100%) on the MoS Scale defined by Prescott-Allen ( 2001 ). If adopted, the ESM model can control the uses of ecotourism resources at the operational level and can also support the local community to sustain their livelihood even in the case of climate change in Himalayan regions as predicted by IPCC ( 2022 ).

Extended use of the results of the ESM Model can only be useful when (a) it is substantially validated, and (b) its applicability (in terms of the performance of the ESIs at the operational level) is assessed on a temporal level. Based on the availability of the field data, the authors will be duly validating and assessing the applicability of the ESM model which may logically be developed as the 3rd and 4th study series in the process of developing an ESAM as per the guidelines given by the BellagioSTAMP 2009. In addition to this, the authors also want to integrate their 4 stage study series of the ESAM with a web-based geospatial platform, to make it a more comprehensive tool for ecotourism sustainability assessment and monitoring. This tool would be assessing the level of ecotourism sustainability based on the spatial information collected for 58 ESIs. Among the 58 ESIs, spatial data for 11 indicators, related to the first criterion, “C1–maintenance of ecosystem health,” can be generated through satellite imagery and its derived products. The spatial data for the rest of the 47 indicators related to seven criteria ranging from “C2–maintenance of local culture” to “C8–conservation management using traditional/indigenous knowledge system” can be generated through crowdsourcing involving ecotourism stakeholders, i.e., tourists, local people (ecotourism service providers, CBOs, tour operators, etc.), government Tourism departments. Thus, it can fulfill the target of SDG 12. b, which mentions “developing and implementing tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism” by fulfilling SDGs 8.9 (ensuring jobs, promotion of local culture and tourism products) and 15 (Protecting, restoring, and managing biodiversity in the terrestrial ecosystem) identified by the report of working group II sustainable tourism in the Indian Himalayan region (NITI Aayog, 2018 ). Through the application of the above “monitoring tool,” deforestation can be controlled, carbon stock can be maintained and the biodiversity-rich areas will be undisturbed so they will regenerate. In turn, it will help optimize biodiversity recovery and livelihood benefits and can play an important role in taking urgent action to mitigate climate change for achieving the targets of SDG 13 in the Indian Himalayan regions.

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Smriti Ashok, Email: [email protected] , Email: moc.liamg@kohsaitirmsrd .

Mukund Dev Behera, Email: ni.ca.pgktii.laroc@arehebdm .

Hare Ram Tewari, Email: moc.liamg@marerahirawet .

Chinmoy Jana, Email: moc.oohay@anajyomnihc .

- Agyeman, Y. B. (2019). Ecotourism as an adaptation strategy for mitigating climate change impacts on local communities around protected areas in Ghana. Handbook of Climate Change Resilience . Cham: Springer. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from 10.1007/978-3-319-71025-9_159-1

- Ashok S, Tewari HR, Behera MD, Majumdar A. Development of ecotourism sustainability assessment framework employing Delphi, C&I and participatory methods: A case study of KBR, West Sikkim, India. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2017; 21 :24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2016.10.005. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berrens RP, Brookshire DS, McKee M, Schmidt C. Implementing the safe minimum standard approach: Two case studies from the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Land Economics. 1998; 74 (2):147–161. doi: 10.2307/3147047. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bertuglia CS, Tadei R, Leonardi G. The optimal management of natural recreation resources: A mathematical model. Environment and Planning. 1980; 13 :69–83. doi: 10.1068/a120069. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhardwaj, M. (2011). Magnitude 6.8 quake in India, several dead . Reuters. Retrieved September 18, 2011, from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-quake-india-idUSTRE78H19D20110918

- Boley BB, Green GT. Ecotourism and natural resource conservation: The “potential” for a sustainable symbiotic relationship. Journal of Ecotourism. 2016; 15 (1):36–50. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2015.1094080. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity. (1992). Convention on biological diversity text . Retrieved September 4, 2021, from https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf

- CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity. (2018). The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development technical note in: biodiversity is essential for sustainable development . Retrieved February 18, 2018, from https://www.cbd.int/development/doc/biodiversity-2030-agenda-technical-note-en.pdf

- Chettri N, Sharma E, Deb DC, Sundriyal RC. Impact of firewood extraction on the tree structure, regeneration and woody biomass productivity in a trekking corridor of the Sikkim Himalaya. Mountain Research and Development. 2002; 22 (2):50–158. doi: 10.1659/0276-4741(2002)022[0150:IOFEOT]2.0.CO;2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciriacy-Wantrup SV. Resource conservation, economics, and policies. University of California Press; 1952. [ Google Scholar ]

- Colfer C, Prabhu R, Wollenberg E. Principles, criteria and indicators: Applying Ockam’s Razor to the people - forestlink. Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Di Sacco A, Hardwick KA, Blakesley D, et al. Ten golden rules for reforestation to optimize carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery and livelihood benefits. Global Change Biology. 2020; 27 :1328–1348. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15498. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eraqi MI. Ecotourism resources management as a way for sustainable tourism development in Egypt. Tourism Analysis. 2007; 12 :39–49. doi: 10.3727/108354207780956681. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- HMI - Himalayan Mountaineering Institute. (2018). Darjeeling . Retrieved September 11, 2018, from https://hmidarjeeling.com

- Hunter C, Green H. Environmental impact of tourism. In: Hunter C, Green H, editors. Tourism and environment: A sustainable relationship? Routledge Publication; 1995. pp. 10–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- IISD - International Institute of Sustainable Development. (2009). Sustainability assessment and measurement of sustainability principle . Retrieved September 18, 2018, from https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2021-08/bellagio-stamp-brochure.pdf

- IPCC. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, sixth assessment report, the working group II . Retrieved March 1, 2022, from https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg2/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FinalDraft_TechnicalSummary.pdf

- Jamaliah MM, Powell RB. Ecotourism resilience to climate change in Dana Biosphere Reserve, Jordan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2018; 26 (4):519–536. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1360893. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jana C, Mahapatra SC, Chattopadhyay RN. Block level energy planning for domestic lighting-a multi-objective fuzzy linear programming approach. Energy. 2004; 29 (11):1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2004.03.095. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiang Y. Evaluating eco-sustainability and its spatial variability in tourism areas: A case study in Lijiang County, China. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 2009; 16 (2):117–126. doi: 10.1080/13504500902808628. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiper, T. (2013). Role of Ecotourism in Sustainable Development. In M. Özyavuz (Ed.), Advances in landscape architecture . INTECH. Retrieved September 11, 2018, from https://www.intechopen.com/books/citations/advances-in-landscape-architecture/role-of-ecotourism-in-sustainable-development

- KNP-RO (Kangchendzonga National Park, Range Office). (2019). Tourist Arrival in Yuksam, West District, Sikkim - from 2008–2019, KNP- Range office, Forest and Environment, Sikkim .

- Kumari S. Identification of potential ecotourism sites, sustainability assessment and management in geospatial environment. Kharagpur, India: Indian Institute of Technology; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumari S, Tewari HR, Inbakaran R. Development of ecotourism sustainability assessment framework: A case study of Kanchendzonga Biosphere Reserve, Sikkim, India. The Indian Geographical Journal. 2005; 80 (2):87–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Munasinghe M, Shearer W. Defining and measuring sustainability. UNU and The World Bank; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- NCAER - National Council of Applied Economic Research. (2021). India and the Coronavirus Pandemic: Economic losses for households engaged in tourism and policies for recovery . India: Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved Januray 25, 2022, from https://www.ncaer.org/study_details.php?pID=84 . Submitted draft report.

- Newsome D, Moore SA, Dowling RK. Natural area tourism: Ecology, impacts and management. Channel View Publications; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- NITI Aayog. (2018). Report of working group II sustainable tourism in the Indian Himalayan region. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/Doc2.pdf

- Overton, M. L. (1997). Linear programming, draft for encyclopedia Americana, December 20, 1997 . Retrieved September 24, 2007, from http://cs.nyu.edu/overton/g22_lp/encyc/node1.html

- Page SJ, Dowling RK. Themes in tourism. Harlow: Pearson education limited; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pandey, D. N. (2000). The measure of success for sustainable forestry: Theory, methods and applications to pursue progress towards sustainability. Training Manual Prepared in IIFM, Bhopal. Himanshu Publication, New Delhi, India

- Perring C. Ecological Economics: The Science and Management of Sustainability. 3. New York: Columbia University Press; 1991. Reserved rationality and the precautionary principle: Technological change, time and uncertainty in environmental decision making. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pigram JJ. Sustainable tourism policy considerations. Journal of Tourism Studies. 1990; 1 (2):2–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinter L, Hardi P, Martinuzzic A, Halla J. Bellagio STAMP: Principles for sustainability assessment and measurement. Ecological Indicators. 2012; 17 :20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.07.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Popova N. Eco-tourism impact/success indicators: Baseline data 2002. Sofia, Bulgaria: Kalofer Pilot Region of Central Balkan National Park; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prabhu R, Colfer CJP, Dudley R. Guidelines for developing, testing and selecting criteria and indicators for sustainable management. Jakarta, Indonesia: CIFOR; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prescott-Allen, R. (1997). Barometer of sustainability: measuring and communicating wellbeing and sustainable development. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from http://hdl.handle.net/10625/54761

- Prescott-Allen, R. (2001). The wellbeing of nations . Island Press and International Development Research Centre. Retrieved August 27, 2005, from http://www.idrc.ca/en/ev-5474-201-1-DO_TOPIC.htm

- QDE - Québec Declaration on Ecotourism. (2002). World Ecotourism Summit (vol. 22). Québec City, Canada. Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://www.gdrc.org/uem/eco-tour/quebec-declaration.pdf

- Singh, R., & Bhutia, K. (2020). COVID -19: With community support and solidarity, Sikkim weathers a lockdown . Retrieved September 9, 2020, from https://science.thewire.in/health/sikkim-covid-19-community-support-solidarity-lockdown-tourism

- Sirakaya E, Jamal TB, Choi HS. Developing indicators for destination sustainability. In: Weaver DB, editor. Encyclopedia of Ecotourism. CABI Publishing; 2001. pp. 411–432. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tambe, S., Bhutia, K. S., & Arrawatia, M. L. (2011). Mainstreaming ecotourism in Sikkim’s economy . Retrieved June 20, 2022, from http://www.sikkimforest.gov.in/docs/Ecotourism/Mainstreaming%20Ecotourism%20in%20Sikkim%E2%80%99s%20Economy.pdf

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity -TEEB. (2009). TEEB climate issues update . Retrieved April 10, 2022, from http://teebweb.org/publications/other/teeb-climate-issues/

- Toman MA. Economics and 'sustainability’: Balancing trade-offs and imperatives. Land Economics. 1994; 70 (4):399–413. doi: 10.2307/3146637. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UNDESA - United Nation-Department of Economic and Social Affairs Development. (2021). Sustainable tourism . Retrieved July 30, 2021, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabletourism

- UNEP. (2002). Sustainable Tourism Development Guidelines: UNEP principles on the implementation of sustainable tourism and the CBD sustainable tourism development guidelines for vulnerable ecosystems . Retrieved January 15, 2007, from http://www.uneptie.org/PC/tourism/policy/cbd_guidelines.htm

- UNWTO. (2011). International Tourists to Hit 1.8 Billion by 2030 . Retrieved July 30, 2021, from https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2011-10-11/international-tourists-hit-18-billion-2030

- UNWTO. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development . Retrieved September 18, 2018, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- UNWTO. (2021). International tourists arrivals: Scenarios for 2021 . Retrieved August 8, 2021, from https://www.unwto.org/taxonomy/term/347

- Walter GR, Schofield JA. Recreation management: A programming example. Land Economics. 1977; 53 (2):212–225. doi: 10.2307/3145925. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wright PA, Alward G, Colby JL, Hoekstra TW, Tegler B, Turner M. Monitoring for forest management unit scale sustainability: The local unit criteria and indicators development (LUCID) test (management edition) Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service; 2002. p. 54. [ Google Scholar ]

- WTO- UNDP - World Tourism Organization, & United Nations Development Programme. (2017). Tourism and the sustainable development goals – Journey to 2030 . Madrid: UNWTO. Retrieved July 30, 2021, from https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284419401

- Zhang H, Song S, Wen L, Liu C. Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research. 2021; 87 :103149. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103149. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Mini review article, protected area tourism and management as a social-ecological complex adaptive system.

- Conservation Social Science Lab, College of Forestry, Wildlife and Environment, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, United States

This article presents a mini review of systems and resilience approaches to tourism analysis and to protected area management, and of how the Social-Ecological Complex Adaptive Systems (SECAS) framework can help link them together. SECAS is a unique framework that integrates social theories (structuration) and ecological theories (hierarchical patch dynamics) and examines inputs, outputs, and feedback across a variety of hierarchically nested social and ecological systems. After an introduction to the need for continued theoretical development, this article continues with a review of the origins and previous applications of the SECAS framework. I subsequently highlight how complex adaptive systems and resilience have been presented in the literature as a way to separately study (1) protected area management, (2) protected area tourism/ecotourism, and (3) land-use change in adjacent forest and agricultural landscapes. The purpose of this article is to build on the frameworks described in this literature and link them through the SECAS framework. I populate the SECAS framework with components identified in the literature on protected area management, ecotourism, and land-use change to present an example of a full systems perspective. Each component also represents a hierarchically nested system, such as a governance system, health system, or transportation system. I conclude with a three-step (5-part) multi-scale and temporal method for SECAS research derived from hierarchy and structuration theories.

Introduction

In their review of the connections between ecotourism and conservation, Stronza et al. (2019) identify a number of research elements that are frequently missing; sometimes these are conducted independently, but it is necessary to conduct them together for rigorous evaluation. These elements include: (1) gathering longitudinal data ( Zambrano et al., 2010 ; Hunt et al., 2015 ), (2) addressing issues of scale ( Hunt and Stronza, 2009 ), (3) studying community outcomes beyond economic impacts ( Lupoli et al., 2015 ), (4) participatory evaluation ( Castro-Arce et al., 2019 ), and (5) addressing the larger social context driving land-use change and deforestation ( Geist and Lambin, 2002 ). Special issues on systems and resilience approaches to protected area management ( Cumming et al., 2015 ; Cumming and Allen, 2017 ) and nature-based tourism ( Morse et al., 2022a ) and the articles therein (i.e., Maciejewski and Cumming, 2016 ; Arlinghaus et al., 2022 ) have advocated for the further development of social-ecological systems (SESs) and resilience frameworks, and for research that explicitly considers hierarchical dynamics and feedback loops and incorporates analysis that considers protected areas and surrounding landscapes where tourism and conservation occur. This article builds on these frameworks and links the bodies of literature on tourism, protected areas, and landscape change through a Social-Ecological Complex Adaptive Systems (SECAS) framework.

The SECAS framework was originally developed to enable an interdisciplinary team to assess the social and ecological impacts of Costa Rica's Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) program ( Morse, 2007 ; Morse et al., 2009 , 2013 ). Ecosystem services are the benefits that people receive from ecosystems, including production (e.g., food, fiber, and timber), regulation (e.g., carbon sequestration and water purification), and cultural services (e.g., aesthetics, tourism, and spiritual services; MEA, 2005 ). In 1996, Costa Rica passed a Forestry Law (no. 7575) that prohibited converting natural forests to other land uses and established one of the first programs that paid landowners directly for providing several environmental services, including watershed protection, biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, and aesthetic values ( Morse et al., 2009 ). Costa Rica targeted the PES program toward a system of biological corridors that linked national parks and other conservation areas. These corridors generally consisted of areas with high forest cover and agricultural land use that were privately owned but located in poorly developed areas of the country. The PES program was designed to enhance conservation and improve local household and community livelihoods in the regions outside of protected areas. Our team research was conducted in the San Juan–La Selva Biological Corridor in northern Costa Rica, where some of the highest concentrations of private forests mixed with agricultural lands connect the highlands of the central volcanic range, including Braulio Carrillo National Park, Volcan Poas National Park, Juan Castro Blanco National Park, and several forest reserves through lowland areas to the Indio Maiz Biological Reserve in Nicaragua along the San Juan River ( Morse et al., 2009 ). A framework was needed to organize our project, which examined how a social conservation policy (PES) could influence landowners' decisions on land use (to reforest pasture or maintain natural forest on their farm), which would then change the land cover (farm by farm) across the landscape over time to have an impact on the desired ecosystem services ( Morse et al., 2013 ). The framework was clearly required to incorporate social and ecological system factors and hierarchical multi-scale considerations (policy-to-household and farm-to-landscape) that changed over time. We needed a SECAS framework.

The initial development of the complex adaptive system (CAS) concept came from ecology ( Holling, 1973 ; Hartvigsen et al., 1998 ; Levin, 1999 ; Gunderson and Holling, 2002 ). CASs are characterized as dynamic, unpredictable, non-linear, multi-scale systems with multiple interacting components, and a lack of central control ( Berkes et al., 2003 ; Norberg and Cumming, 2008 ). A CAS is defined by the presence of a network of interactions and relationships among the multiple components ( Meadows, 2008 ; Preiser et al., 2018 ). CASs adapt over time through recursive interactions and feedback between components, and between components and their environment, leading to emergent or novel patterns ( Levin, 1998 ; Walker et al., 2004 ). CASs are open systems, and dynamic interactions occur across multiple scales, allowing them to self-organize, often into nested hierarchies ( Folke et al., 2005 ). CASs are considered to be non-linear, meaning that cause and effect are not always proportional, and small changes can lead to bigger impacts (or vice versa) on other components or on the whole system ( Levin et al., 2013 ). Interactions can take the form of slow or fast variables and can occur across spatial scales ( Gunderson and Holling, 2002 ). Non-linearity leads to complexity, unpredictability, and uncertainty within and about the system ( Walker et al., 2006 ). The term adaptive indicates that a CAS can change, evolve, and self-organize over time in response to feedback ( Preiser et al., 2018 ). Similar to ecological systems, social systems have multiple interacting components across multiple scales, are dynamic, and change over time ( Berkes et al., 2003 ). SESs are considered to be inextricably linked, and together, these systems are considered to be CASs ( Gunderson and Holling, 2002 ; Berkes et al., 2003 ; Folke, 2006 ; Norberg and Cumming, 2008 ; Preiser et al., 2018 ). The concept of resilience is a way to frame SECAS that explicitly recognizes uncertainty, complexity, and change ( Walker et al., 2006 ). Resilience has been defined as the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and maintain the same identity or the same function, structure, and feedbacks ( Walker et al., 2006 ). Resilience also describes the degree to which a system can self-organize and its ability to build its capacity to adapt or learn ( Carpenter et al., 2001 ). Resilience has become a goal in managing CASs ( Lew et al., 2016 ).

Managing protected areas and tourism as complex adaptive systems

Social-ecological systems, complex adaptive systems, and resilience have been promoted as frameworks for research on and management of protected areas and for tourism based in protected areas ( McKercher, 1999 ; Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004 ; McCool et al., 2013 ; Cumming et al., 2015 ; McCool and Bosak, 2016 ; Bosak, 2019 ). To address biodiversity conservation and protected area management, Cumming et al. (2015) proposed a framework to capture the multi-scale SESs that extend beyond the boundaries of protected areas into the “functional landscapes” (nearby forests, farms, and communities) necessary for conservation and support of the protected area. The authors build on Ostrom (2009) SES framework and address some of the concerns for application by adding five hierarchical levels (patch, protected area, protected area network, national, and international/global) and highlighting temporal dynamics and cross-scale interactions ( Cumming et al., 2015 ). Research from an ecosystem conservation perspective expands the interests in protected area management beyond the administrative boundaries of the area into human-dominated landscapes, as linked SESs focus on cross-scale feedback ( Maciejewski and Cumming, 2016 ), ecological solidarity ( Mathevet et al., 2016 ), and resilience ( Cumming and Allen, 2017 ).

In a seminal article reconceptualizing theoretical frameworks in tourism, Farrell and Twining-Ward (2004) specifically identify the need to fully consider SESs and frame research around the process, transition, or journey of dynamic complex adaptive systems. The authors draw parallels from CASs in ecology with tourism systems, introduce the concept of resilience, and develop their own Complex Adaptive Tourism Systems (CATS) model to address tourism systems more comprehensively ( Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004 ). Strickland-Munro et al. (2010) also assesses protected area tourism and local community interactions as multi-scale embedded CASs with two case studies in national parks in South Africa and Australia. Following others, the author emphasizes the importance of resilience thinking ( Walker et al., 2006 ) in understanding continually adapting tourism systems ( Plummer and Fennell, 2009 ). Strickland-Munro et al. (2010) develops a four-step model for research that includes (1) system definition, (2) past system change, (3) current system state, and (4) monitoring of change. Lew (2014) and Lew et al. (2016) emphasize the importance of spatial scale and of an understanding of fast and slow variables; they also emphasize how a resilience perspective will help in placing focus on adaptive management within ever-changing tourism CASs. McCool et al. (2013 , 2015) and McCool and Bosak (2016) argue that framing protected area management and tourism research from a systems perspective (employing the frameworks of SES, CAS, and resilience) is essential in order to counter past reductionist perspectives and provide managers with meaningful leverage points to target resilience-building in these systems. These articles also discuss the difficulties involved and the need to work with the public and use systems frameworks to make sense of dynamic and complex contexts ( McCool et al., 2013 ), address the challenges of systems work ( McCool, 2022 ), and identify bridges and barriers to conducting interdisciplinary research ( Morse et al., 2007 ). McCool et al. (2015) provide a set of six “complexity practices” to help frame CASs and manage them toward resilience, namely, (1) building situational awareness, (2) investing in personal relationships, (3) appreciating the power of networks, (4) identifying and using leverage points, (5) employing different forms of knowledge, and (6) learning continuously.

The social-ecological complex adaptive systems framework

The Social-Ecological Complex Adaptive Systems (SECAS) framework was designed based on the fundamental principles of the CAS framework ( Gunderson and Holling, 2002 ; Berkes et al., 2003 ; Levin, 2005 ). It was designed to be multi-scale and to integrate across dynamic and non-linear social and ecological systems, with inputs and outcomes across scales and systems ( Morse et al., 2013 ). Visually and conceptually, the framework was based on research by Grimm et al. (2000) on change in land use and land cover, and on research by Ostrom (2007) on linked SESs. Theoretically, our research group used structuration theory from the social sciences to explain social CASs ( Giddens, 1984 ; Stones, 2005 ), because humans can and do act with foresight and intent, meaning that social and ecological systems are fundamentally different in terms of the drivers of self-organization ( Walker et al., 2006 ). Structuration theory had been identified by others as suitable for linking social and ecological systems ( Bebbington, 1999 ; Scoones, 1999 ; Scheffer et al., 2002 ; Westley et al., 2002 ), and we elaborated on and updated their contributions to include revisions to structuration theory made by Stones (2005) . “A defining characteristic of structuration theory is that through recursive social practice or action, social systems (structures) influence the activity of individuals, who in turn, produce, transform, or otherwise reaffirm those same structures constantly producing and reproducing society” ( Morse et al., 2013 . p. 58). We retain the descriptors “social” and “ecological” (SE) in front of “CAS” in order to highlight the differences in terms of drivers of self-organization. On the ecological side of the SECAS framework, we applied the theory of hierarchical patch dynamics (HPD), where each patch (farm) is nested in a dynamic patch mosaic (landscape), which is again nested in a higher-level patch mosaic (at the national level; Pickett and White, 1985 ; Wu and Loucks, 1995 ; Morse et al., 2013 ).

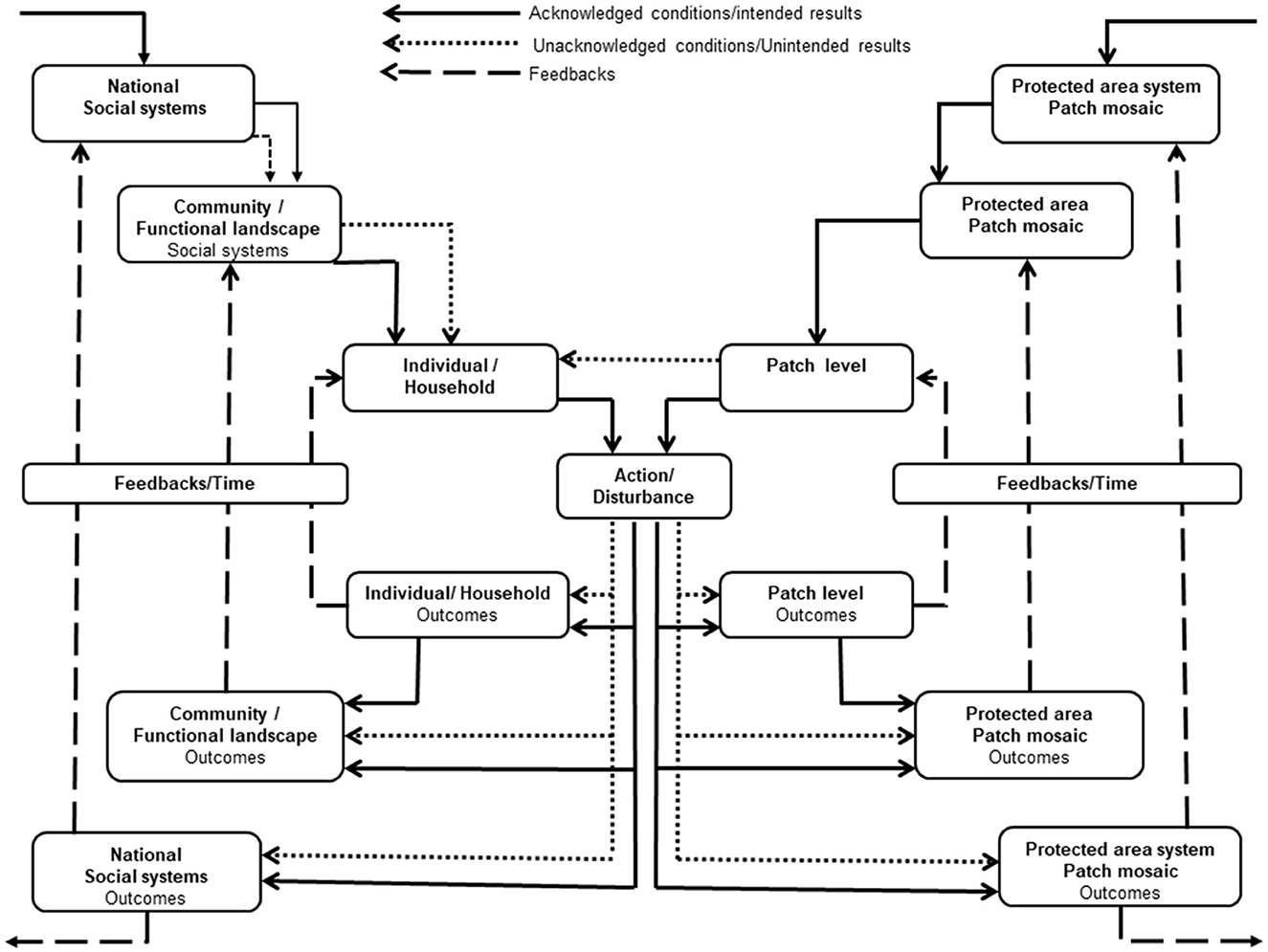

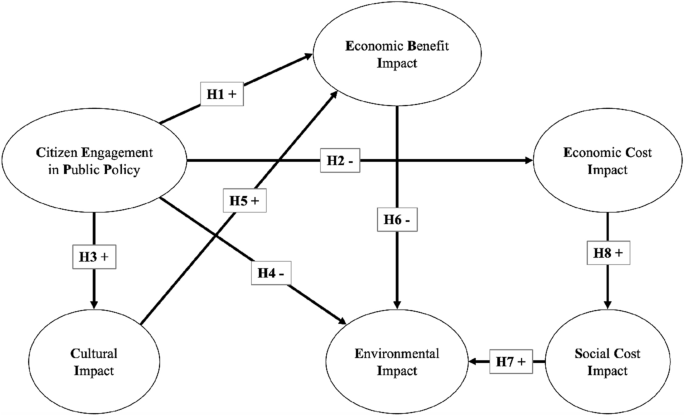

A base SECAS model that demonstrates the linking of social and ecological systems across scales is presented in Figure 1 . The left-hand side of the model represents hierarchically nested social systems, and the right-hand side represents ecological systems in terms of nested patch mosaics. The top of the model illustrates the inputs to an action, and the bottom half represents the outcomes of that action. Actions are modeled as having outcomes that impact both systems and all levels simultaneously, as each is a nested part of the other. In the CAS framework, our knowledge of external social and ecological systems is seen as incomplete, and the outcomes of our actions may be intended or unintended ( Morse et al., 2013 ).

Figure 1 . Base SECAS model.

Since the inception of the SECAS framework ( Morse, 2007 ), I have collaborated with others to place existing recreation models into a systems perspective and to integrate them with a cultural recreation ecosystem services perspective ( Morse et al., 2022b ). McCool et al. (2013) recognize that many of the tools used to manage outdoor recreation are linear and reductionist and do not take a systems approach. The SECAS model has been applied to outline how a number of these recreation tools and constructs, such as the recreation experience model, beneficial outcomes, the recreation opportunity spectrum, limits of acceptable change, and constraints theory, could all be framed together into a unified systems perspective ( Morse, 2020 ). A second application of the SECAS model to recreation is in examining how the field of outdoor recreation research and the concept of recreation ecosystem services could be better integrated ( Morse et al., 2022b ). This work has further integrated components of recreation management into the SECAS framework, extended the framework to consider outdoor recreation and the corresponding tools and theory as they apply to nature tourism, and added protected area and protected area management as a third dimension. Furthermore, the article presents the idea of transformation at the center of the recreation experience to highlight the experiential and dynamic nature (as a process or journey) of outdoor recreation and nature tourism ( Morse et al., 2022b ). While this last application of the SECAS framework does address protected areas and their management, it still considers the entirety of the tourism system in individual boxes on the social side of the model. The current article conceptualizes the tourism system in accordance with the literature on tourism systems and protected area systems, and integrates this with a meta analysis of the drivers of land-use and land-cover change to further frame the ways in which the landscape changes around a protected area with tourism.

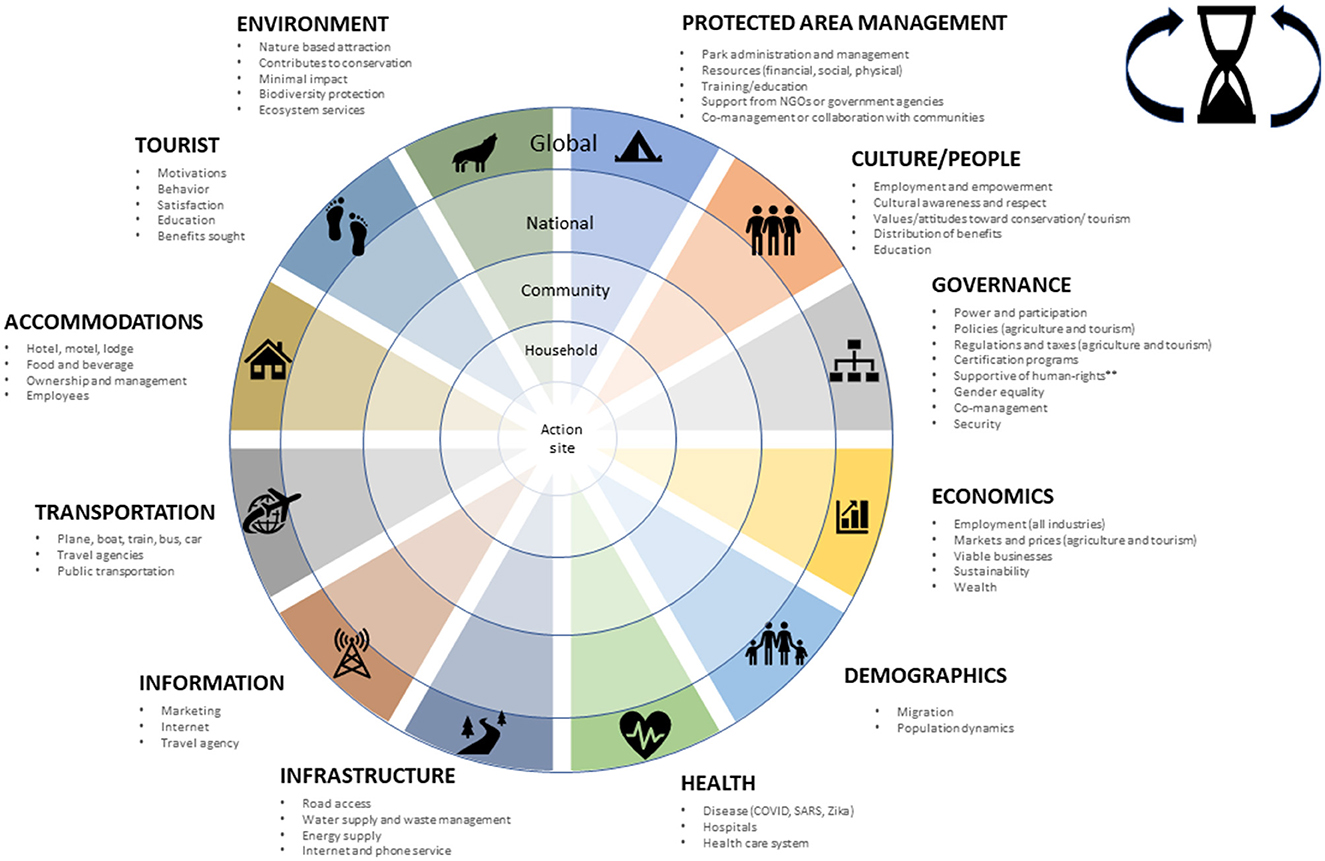

SECAS for protected area management and nature tourism

Once the general model is understood, it must be populated with variables that are important to the relevant research questions across scales and systems. If i want to understand the interactions between tourism, conservation, protected area management, and the environment as a SECAS, i need to understand the drivers of agriculture and forest management in the functional landscapes outside of protected areas, how the tourism system impacts local communities and protected areas, and even how the tourist navigates the system through components of the traditional tourism industry. I began by identifying and consolidating the major subsystems identified in the literature on land use and land cover outside protected areas ( Geist and Lambin, 2002 ), items mentioned as critical for ecotourism as a form of tourism closely associated with protected areas ( Honey, 2008 ; Fennell, 2020 ), and items mentioned in the protected area and tourism CAS literature that was reviewed. The major change to the SECAS model is to move beyond generic two-dimensional representations of social and ecological systems and identify the many other social systems that are important for conservation and tourism around a protected area. I identified 12 major component categories of social systems from the literature (others could be included); these are presented in Figure 2 .

Figure 2 . Major tourism and protected area component categories.

Each social subsystem could be modeled as a nested hierarchy with inputs and outcomes, as in the current SECAS framework (all subsystems could make up their own hierarchically nested “side” of the original framework). With all the subsystems included together, the model would be visualized as a sphere with a funnel or hourglass through the middle. For example, park management is its own hierarchically nested social system, from the management of an individual setting (patch), to an individual park, to the park system across a country, to its implications at the global level ( Morse et al., 2022b ). Governance systems are frequently hierarchically nested. Similarly, tourism accommodations are a hierarchically nested social system with different types and amounts offered at different scales. Ecological systems could similarly be expanded to address watersheds, habitats, and biodiversity as hierarchically nested systems. The side-by-side stepped framework captures the dynamic system with inputs, outcomes, and feedback pathways in two dimensions, while the 12-piece pie chart shows all the different subsystems and how they come together across scales. This view from the top ( Figure 2 ) can be imagined as an open hourglass, seen from above: the center is where all the different variables come together to form a tourism experience and where the sand flows down to the next level to produce outcomes for all the different systems. Feedback loops refill the top half with sand, enabling the process to continue recursively, as tourism, park management, and conservation are part of a continually updated SECAS (input, action, outcome, and feedback).

How to study the SECAS

Where in the system, or what scale, you want to focus your analysis is dependent on the research question at issue. HPD ( Wu and Loucks, 1995 ) has a multi-scale analysis protocol of “enveloping,” while structuration theory ( Giddens, 1984 ; Stones, 2005 ) has “methodological bracketing.” Both approaches indicate that multiple levels of analysis are needed to understand a CAS, including the external environment, which provides the conditions for any action/disturbance, and the mechanism that describes how and why things happen at a lower level. Stones (2005) developed methods for analysis of actors' conduct and for context analysis from Giddens's (1984) methodological brackets, and these approaches help in representing the steps for analysis that we outline below. These steps address items from the four-step model of Strickland-Munro et al. (2010) and the six “complexity practices” proposed by McCool et al. (2015) . These steps extend these previous models by adding temporal analysis (historical and future), a purposefully scaled analysis, and multiple viewpoints. The steps also address each of the five components that were identified as lacking in rigorous studies on tourism and conservation systems by Stronza et al. (2019) . The steps can be used for both social and ecological systems analysis.

Step 1. Context analysis

The context analysis is designed to examine enabling and constraining conditions of the external context for actions ( Stones, 2005 ). This step helps to define the system. Context analysis should be derived from both the researchers' perspectives (from the outside looking in) and the actors' perspectives (from the inside looking out; Stones, 2005 ).

Past system change: the researcher's historical perspective

To understand how systems change (a slower process) and the influence of feedback over time, a more historical perspective is needed. Examination of the “intermediate temporality” would allow reflection on how social systems enabled or constrained or reacted to different actors' actions ( Stones, 2005 ). This can be done through literature reviews, policy analysis, and other external analyses. Similar historical analysis can be done for land use change, biodiversity trends, and other ecological assessments.

Building situational awareness

It is also important to obtain multiple perspectives of the current situation at the systems level. For example, interviews, focus groups, and group mapping exercises with government agricultural agencies, non-governmental conservation organizations, and protected area managers can provide new insight as to the specific social systems variables (i.e., policies, markets, and land tenure) that are influencing the system ( Morse et al., 2013 ). This level of analysis helps to build personal relationships and understand power relations and social networks ( McCool et al., 2015 ). Parallel analyses with many of these same groups can explore environmental issues in that local context identifying underlying and proximate drivers, feedback, and change.

The actors' perspective