The future of tourism: Bridging the labor gap, enhancing customer experience

As travel resumes and builds momentum, it’s becoming clear that tourism is resilient—there is an enduring desire to travel. Against all odds, international tourism rebounded in 2022: visitor numbers to Europe and the Middle East climbed to around 80 percent of 2019 levels, and the Americas recovered about 65 percent of prepandemic visitors 1 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. —a number made more significant because it was reached without travelers from China, which had the world’s largest outbound travel market before the pandemic. 2 “ Outlook for China tourism 2023: Light at the end of the tunnel ,” McKinsey, May 9, 2023.

Recovery and growth are likely to continue. According to estimates from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2023, international tourist arrivals could reach 80 to 95 percent of prepandemic levels depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, travel recovery in Asia–Pacific, and geopolitical tensions, among other factors. 3 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) forecasts that by the end of 2023, nearly half of the 185 countries in which the organization conducts research will have either recovered to prepandemic levels or be within 95 percent of full recovery. 4 “Global travel and tourism catapults into 2023 says WTTC,” World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), April 26, 2023.

Longer-term forecasts also point to optimism for the decade ahead. Travel and tourism GDP is predicted to grow, on average, at 5.8 percent a year between 2022 and 2032, outpacing the growth of the overall economy at an expected 2.7 percent a year. 5 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 , WTTC, August 2022.

So, is it all systems go for travel and tourism? Not really. The industry continues to face a prolonged and widespread labor shortage. After losing 62 million travel and tourism jobs in 2020, labor supply and demand remain out of balance. 6 “WTTC research reveals Travel & Tourism’s slow recovery is hitting jobs and growth worldwide,” World Travel & Tourism Council, October 6, 2021. Today, in the European Union, 11 percent of tourism jobs are likely to go unfilled; in the United States, that figure is 7 percent. 7 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022.

There has been an exodus of tourism staff, particularly from customer-facing roles, to other sectors, and there is no sign that the industry will be able to bring all these people back. 8 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022. Hotels, restaurants, cruises, airports, and airlines face staff shortages that can translate into operational, reputational, and financial difficulties. If unaddressed, these shortages may constrain the industry’s growth trajectory.

The current labor shortage may have its roots in factors related to the nature of work in the industry. Chronic workplace challenges, coupled with the effects of COVID-19, have culminated in an industry struggling to rebuild its workforce. Generally, tourism-related jobs are largely informal, partly due to high seasonality and weak regulation. And conditions such as excessively long working hours, low wages, a high turnover rate, and a lack of social protection tend to be most pronounced in an informal economy. Additionally, shift work, night work, and temporary or part-time employment are common in tourism.

The industry may need to revisit some fundamentals to build a far more sustainable future: either make the industry more attractive to talent (and put conditions in place to retain staff for longer periods) or improve products, services, and processes so that they complement existing staffing needs or solve existing pain points.

One solution could be to build a workforce with the mix of digital and interpersonal skills needed to keep up with travelers’ fast-changing requirements. The industry could make the most of available technology to provide customers with a digitally enhanced experience, resolve staff shortages, and improve working conditions.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

Complementing concierges with chatbots.

The pace of technological change has redefined customer expectations. Technology-driven services are often at customers’ fingertips, with no queues or waiting times. By contrast, the airport and airline disruption widely reported in the press over the summer of 2022 points to customers not receiving this same level of digital innovation when traveling.

Imagine the following travel experience: it’s 2035 and you start your long-awaited honeymoon to a tropical island. A virtual tour operator and a destination travel specialist booked your trip for you; you connected via videoconference to make your plans. Your itinerary was chosen with the support of generative AI , which analyzed your preferences, recommended personalized travel packages, and made real-time adjustments based on your feedback.

Before leaving home, you check in online and QR code your luggage. You travel to the airport by self-driving cab. After dropping off your luggage at the self-service counter, you pass through security and the biometric check. You access the premier lounge with the QR code on the airline’s loyalty card and help yourself to a glass of wine and a sandwich. After your flight, a prebooked, self-driving cab takes you to the resort. No need to check in—that was completed online ahead of time (including picking your room and making sure that the hotel’s virtual concierge arranged for red roses and a bottle of champagne to be delivered).

While your luggage is brought to the room by a baggage robot, your personal digital concierge presents the honeymoon itinerary with all the requested bookings. For the romantic dinner on the first night, you order your food via the restaurant app on the table and settle the bill likewise. So far, you’ve had very little human interaction. But at dinner, the sommelier chats with you in person about the wine. The next day, your sightseeing is made easier by the hotel app and digital guide—and you don’t get lost! With the aid of holographic technology, the virtual tour guide brings historical figures to life and takes your sightseeing experience to a whole new level. Then, as arranged, a local citizen meets you and takes you to their home to enjoy a local family dinner. The trip is seamless, there are no holdups or snags.

This scenario features less human interaction than a traditional trip—but it flows smoothly due to the underlying technology. The human interactions that do take place are authentic, meaningful, and add a special touch to the experience. This may be a far-fetched example, but the essence of the scenario is clear: use technology to ease typical travel pain points such as queues, misunderstandings, or misinformation, and elevate the quality of human interaction.

Travel with less human interaction may be considered a disruptive idea, as many travelers rely on and enjoy the human connection, the “service with a smile.” This will always be the case, but perhaps the time is right to think about bringing a digital experience into the mix. The industry may not need to depend exclusively on human beings to serve its customers. Perhaps the future of travel is physical, but digitally enhanced (and with a smile!).

Digital solutions are on the rise and can help bridge the labor gap

Digital innovation is improving customer experience across multiple industries. Car-sharing apps have overcome service-counter waiting times and endless paperwork that travelers traditionally had to cope with when renting a car. The same applies to time-consuming hotel check-in, check-out, and payment processes that can annoy weary customers. These pain points can be removed. For instance, in China, the Huazhu Hotels Group installed self-check-in kiosks that enable guests to check in or out in under 30 seconds. 9 “Huazhu Group targets lifestyle market opportunities,” ChinaTravelNews, May 27, 2021.

Technology meets hospitality

In 2019, Alibaba opened its FlyZoo Hotel in Huangzhou, described as a “290-room ultra-modern boutique, where technology meets hospitality.” 1 “Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has a hotel run almost entirely by robots that can serve food and fetch toiletries—take a look inside,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019; “FlyZoo Hotel: The hotel of the future or just more technology hype?,” Hotel Technology News, March 2019. The hotel was the first of its kind that instead of relying on traditional check-in and key card processes, allowed guests to manage reservations and make payments entirely from a mobile app, to check-in using self-service kiosks, and enter their rooms using facial-recognition technology.

The hotel is run almost entirely by robots that serve food and fetch toiletries and other sundries as needed. Each guest room has a voice-activated smart assistant to help guests with a variety of tasks, from adjusting the temperature, lights, curtains, and the TV to playing music and answering simple questions about the hotel and surroundings.

The hotel was developed by the company’s online travel platform, Fliggy, in tandem with Alibaba’s AI Labs and Alibaba Cloud technology with the goal of “leveraging cutting-edge tech to help transform the hospitality industry, one that keeps the sector current with the digital era we’re living in,” according to the company.

Adoption of some digitally enhanced services was accelerated during the pandemic in the quest for safer, contactless solutions. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a restaurant designed to keep physical contact to a minimum used a track system on the ceiling to deliver meals directly from the kitchen to the table. 10 “This Beijing Winter Games restaurant uses ceiling-based tracks,” Trendhunter, January 26, 2022. Customers around the world have become familiar with restaurants using apps to display menus, take orders, and accept payment, as well as hotels using robots to deliver luggage and room service (see sidebar “Technology meets hospitality”). Similarly, theme parks, cinemas, stadiums, and concert halls are deploying digital solutions such as facial recognition to optimize entrance control. Shanghai Disneyland, for example, offers annual pass holders the option to choose facial recognition to facilitate park entry. 11 “Facial recognition park entry,” Shanghai Disney Resort website.

Automation and digitization can also free up staff from attending to repetitive functions that could be handled more efficiently via an app and instead reserve the human touch for roles where staff can add the most value. For instance, technology can help customer-facing staff to provide a more personalized service. By accessing data analytics, frontline staff can have guests’ details and preferences at their fingertips. A trainee can become an experienced concierge in a short time, with the help of technology.

Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential

According to Skift Research calculations, total revenue generated by guest apps and in-room technology in 2019 was approximately $293 million, including proprietary apps by hotel brands as well as third-party vendors. 1 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. The relatively low market penetration rate of this kind of tech points to around $2.4 billion in untapped revenue potential (exhibit).

Even though guest-facing technology is available—the kind that can facilitate contactless interactions and offer travelers convenience and personalized service—the industry is only beginning to explore its potential. A report by Skift Research shows that the hotel industry, in particular, has not tapped into tech’s potential. Only 11 percent of hotels and 25 percent of hotel rooms worldwide are supported by a hotel app or use in-room technology, and only 3 percent of hotels offer keyless entry. 12 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. Of the five types of technology examined (guest apps and in-room tech; virtual concierge; guest messaging and chatbots; digital check-in and kiosks; and keyless entry), all have relatively low market-penetration rates (see sidebar “Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential”).

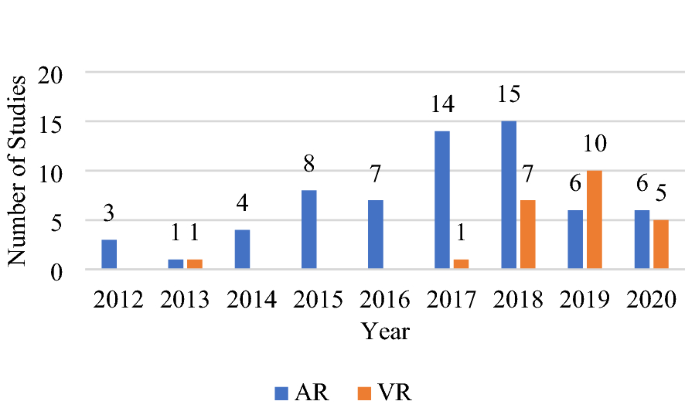

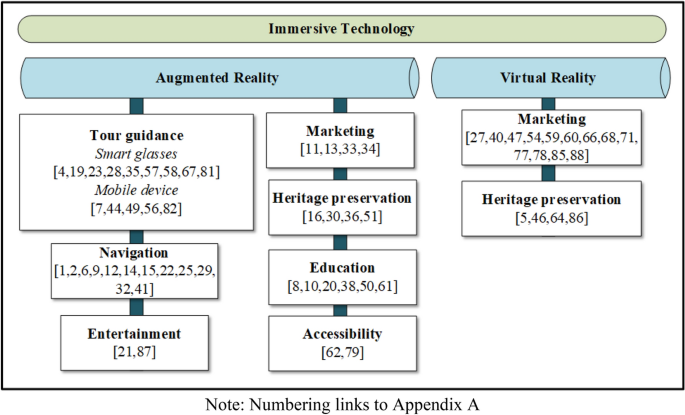

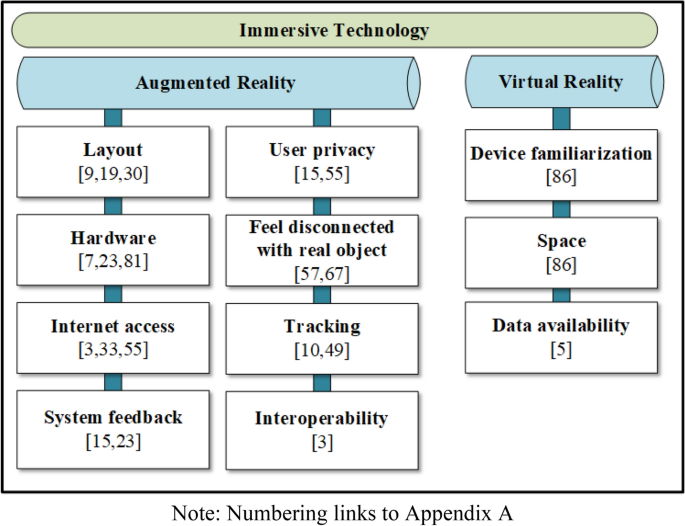

While apps, digitization, and new technology may be the answer to offering better customer experience, there is also the possibility that tourism may face competition from technological advances, particularly virtual experiences. Museums, attractions, and historical sites can be made interactive and, in some cases, more lifelike, through AR/VR technology that can enhance the physical travel experience by reconstructing historical places or events.

Up until now, tourism, arguably, was one of a few sectors that could not easily be replaced by tech. It was not possible to replicate the physical experience of traveling to another place. With the emerging metaverse , this might change. Travelers could potentially enjoy an event or experience from their sofa without any logistical snags, and without the commitment to traveling to another country for any length of time. For example, Google offers virtual tours of the Pyramids of Meroë in Sudan via an immersive online experience available in a range of languages. 13 Mariam Khaled Dabboussi, “Step into the Meroë pyramids with Google,” Google, May 17, 2022. And a crypto banking group, The BCB Group, has created a metaverse city that includes representations of some of the most visited destinations in the world, such as the Great Wall of China and the Statue of Liberty. According to BCB, the total cost of flights, transfers, and entry for all these landmarks would come to $7,600—while a virtual trip would cost just over $2. 14 “What impact can the Metaverse have on the travel industry?,” Middle East Economy, July 29, 2022.

The metaverse holds potential for business travel, too—the meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector in particular. Participants could take part in activities in the same immersive space while connecting from anywhere, dramatically reducing travel, venue, catering, and other costs. 15 “ Tourism in the metaverse: Can travel go virtual? ,” McKinsey, May 4, 2023.

The allure and convenience of such digital experiences make offering seamless, customer-centric travel and tourism in the real world all the more pressing.

Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages

Is the future contactless.

Given the advances in technology, and the many digital innovations and applications that already exist, there is potential for businesses across the travel and tourism spectrum to cope with labor shortages while improving customer experience. Process automation and digitization can also add to process efficiency. Taken together, a combination of outsourcing, remote work, and digital solutions can help to retain existing staff and reduce dependency on roles that employers are struggling to fill (exhibit).

Depending on the customer service approach and direct contact need, we estimate that the travel and tourism industry would be able to cope with a structural labor shortage of around 10 to 15 percent in the long run by operating more flexibly and increasing digital and automated efficiency—while offering the remaining staff an improved total work package.

Outsourcing and remote work could also help resolve the labor shortage

While COVID-19 pushed organizations in a wide variety of sectors to embrace remote work, there are many hospitality roles that rely on direct physical services that cannot be performed remotely, such as laundry, cleaning, maintenance, and facility management. If faced with staff shortages, these roles could be outsourced to third-party professional service providers, and existing staff could be reskilled to take up new positions.

In McKinsey’s experience, the total service cost of this type of work in a typical hotel can make up 10 percent of total operating costs. Most often, these roles are not guest facing. A professional and digital-based solution might become an integrated part of a third-party service for hotels looking to outsource this type of work.

One of the lessons learned in the aftermath of COVID-19 is that many tourism employees moved to similar positions in other sectors because they were disillusioned by working conditions in the industry . Specialist multisector companies have been able to shuffle their staff away from tourism to other sectors that offer steady employment or more regular working hours compared with the long hours and seasonal nature of work in tourism.

The remaining travel and tourism staff may be looking for more flexibility or the option to work from home. This can be an effective solution for retaining employees. For example, a travel agent with specific destination expertise could work from home or be consulted on an needs basis.

In instances where remote work or outsourcing is not viable, there are other solutions that the hospitality industry can explore to improve operational effectiveness as well as employee satisfaction. A more agile staffing model can better match available labor with peaks and troughs in daily, or even hourly, demand. This could involve combining similar roles or cross-training staff so that they can switch roles. Redesigned roles could potentially improve employee satisfaction by empowering staff to explore new career paths within the hotel’s operations. Combined roles build skills across disciplines—for example, supporting a housekeeper to train and become proficient in other maintenance areas, or a front-desk associate to build managerial skills.

Where management or ownership is shared across properties, roles could be staffed to cover a network of sites, rather than individual hotels. By applying a combination of these approaches, hotels could reduce the number of staff hours needed to keep operations running at the same standard. 16 “ Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages ,” McKinsey, April 3, 2023.

Taken together, operational adjustments combined with greater use of technology could provide the tourism industry with a way of overcoming staffing challenges and giving customers the seamless digitally enhanced experiences they expect in other aspects of daily life.

In an industry facing a labor shortage, there are opportunities for tech innovations that can help travel and tourism businesses do more with less, while ensuring that remaining staff are engaged and motivated to stay in the industry. For travelers, this could mean fewer friendly faces, but more meaningful experiences and interactions.

Urs Binggeli is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Zurich office, Zi Chen is a capabilities and insights specialist in the Shanghai office, Steffen Köpke is a capabilities and insights expert in the Düsseldorf office, and Jackey Yu is a partner in the Hong Kong office.

Explore a career with us

Knowledge Transfer to and within Tourism: Volume 8

Academic, industry and government bridges, table of contents, part i introduction, introduction: tourism knowledge transfer, part ii academic led transfer, experience design: academic-industry research collaboration for tourism innovation.

This chapter discusses innovation within the tourism small business sector and provides a case study of academic-industry research collaboration and knowledge transfer. Governments of many countries are interested in improving innovation in the tourism industry. Academics have important skills useful for developing innovative new products. However, collaboration between academic and industry partners is complex and difficult to effectively operationalize. A thriving and innovative new experience for Chinese tourists to Australia’s Gold Coast provides evidence of the characteristics of collaboration needed for successful academic-industry innovation.

Knowledge Transfer: Can Research Centers Make a Difference?

A number of tourism researchers have suggested that despite the proliferation of research in the field, the exchange of knowledge from academic research to practical application in the industry is poor. The argument made is that academic research seldom influences the real world of practice, and that for knowledge transfer to assist destinations a paradigm shift is required. This chapter takes a look at the challenges of knowledge transfer in tourism and focuses on a unique research center in South Carolina, where private and public sectors have joined together in an effort to support applied and commercially relevant research in order to improve the competitiveness of the state as a destination.

“Best Green”: Synergy Between Academia and a Hotel Chain

In 2010, as a response to global mega trends, the Best Western International central office requested all of its offices worldwide to implement environmental programs. The Mexico, Central America, and Ecuador offices consulted with Universidad del Caribe about the best way to fulfill this request and as a result a collaborative project began. A few months later, a Best Environmental Practices Manual (according to the Best Western operational practices and international environmental standards) was developed, together with the Best Green (BG) award and the implementation and external evaluation process. The corporate office evaluated the award and selected it together with the eight recognized international ecolabels, including it as part of its operation. They also promoted and sold awarded hotels as green products. After more than three years of working with the program in the regopm, 49 hotels have obtained the award and 13 have revalidated this certification. Unfortunately, for many external reasons, the program was suspended in 2014. However, this experience offers many valuable lessons in the collaboration among sectors and helps close the gap between theory and praxis and to make more effective collaboration process to increase tourism competitiveness.

Knowledge Transfer between Educational Institutions and Destinations

This chapter investigates the outcome of the ongoing interactions between the Danish University College of Northern Denmark and stakeholder networks in the Italian destination Campi Flegrei. The findings of this study show that the benefits of the interactions among students, lecturers, and destination stakeholders are manifold and show that the challenge resides in strengthening the flux of knowledge sent back to destination stakeholders. Thus, the authors suggest an action- and stakeholder-oriented approach for future knowledge transfer from the educational institution to the destination stakeholders.

Tourism Microentrepreneurship Knowledge Cogeneration

Rural subaltern people are generally relegated to the role of passive tourees, allowed to informally glean bits of income not worthwhile to the formal tourism industry. However, under some circumstances, microentrepreneurs find ways to take advantage of opportunities afforded by tourism to improve their livelihoods and gain human agency. The People-First Tourism Lab employs a participatory action research methodology to investigate tourism microentrepreneurship and its effect on participating individuals and communities. In this chapter, the authors provide a background of the project implemented in the State of North Carolina, USA, explain the research methodology, and outline current and forthcoming efforts.

Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Knowledge Transfer

This chapter examines the development of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and the knowledge transfer process involved, in the tourist municipality of Lagos, Portugal. Participatory action research is used to identify issues, antagonistic forces, and the system of governance which emerged in the creation of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The different roles of both public and private actors were identified. Despite a deficit of entrepreneurial culture and social capital, the main results show that participatory action research encouraged knowledge transfer among political actors, entrepreneurs, and academics, leading to the implementation of the basic conditions for an entrepreneurial ecosystem dynamic.

Tourism Knowledge Transfer in Brazil: The Gap between Academy and Industry

Brazilian higher education in the field of tourism took off in the 1970s, reaching its course and student peaks in the first years of this century. Recent research shows, however, that many graduates are still occupying hotel reception positions, in most cases with an operational status. The Brazilian government will occasionally hire researchers from companies and institutes not related to the tourism field. Even though the link between these two worlds is crucial, the commercial tourism industry in Brazil does not value academic insights, and the academy does not look beyond its epistemological and theoretical borders. This chapter will discuss the situation in Brazil and offer perspectives on measure needed to close the gap between theory and practice.

Part III Public-Private Partnerships for Knowledge Transfer

Collaborative strategy for tourism development and regeneration: italy’s coast of naples.

Cities by the sea have a strong identity which comes from the historic relationship between an urban community and the ocean and is important in attracting tourists. This chapter analyzes urban regeneration, waterfront redevelopment, touristic valorization, and marketing strategies used by seaside cities that, by sharing their maritime culture, have achieved integrated urban transformations. This is facilitated by developing a “collaborative commons” of producers and consumers for the touristic enhancement of the metropolitan area such as Naples.

Tourism Innovation-Oriented Public-Private Partnerships for Smart Destination Development

The chapter aims at advancing existing knowledge on innovation-oriented public-private partnerships for developing smart tourism services at destination level. Recent research has emphasized to the importance of collaborative arrangements involving public sector organizations and private companies for the development of new or improved ICT-enabled tourism services towards the smart transformation of destinations. However, knowledge on public-private partnerships specifically set up for realizing smart innovations is still scarce. This chapter develops a framework for understanding the nature and functioning of this type of partnerships at destination level by integrating literature on tourism partnerships, smart tourism, and innovation in services with a case study of a successful partnership in the Italian destination of Siracusa.

The Destination Triangle: Toward Relational Management

Destinations are highly dynamic and complex systems requiring a responsive and relational governance system. Recent tourism literature proposes a network approach to destination management, but empirical evidence shows interactions in destinations remains low. Dominant stakeholders tend to control destination governance systems; less powerful ones are not actively included. This chapter schematizes the network of relations as a destination triangle made up of governance, supply side, and tourists. A quantitative study of tourists and a qualitative study of supply-side stakeholders show that the destination triangle is inappropriately adjusted. The supply side is not actively involved in destination management. The findings show that the absence of a relational management approach can impede initiatives.

Strategic and Participative Planning in la Comarca de Los Alerces: The Process and Outcomes

Tourism planning is an important issue for destination management organizations to satisfy both local community and tourists. This chapter attempts to explain the process and outcomes of a strategic and participative tourism planning project through a case study in Patagonia, Argentina. The general framework of the study, principles of cooperation throughout the project, the geographical information, stages of planning and implementation strategies will be discussed.

Intelligent Governance for Rural Destinations: Lessons from Europe

One of the main challenges of “good tourism intelligence governance” is to balance and manage the interests of private enterprises, public administrations, and civil society, and to find the right mix between strategic and operational governance. An innovative governance model was introduced in 2011 in emerging rural destinations within the three years’ European project “Listen to the Voice of Villages.” By means of in-depth interviews carried out in summer 2014 in Italy, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia, this chapter investigates how this model of governance was deployed and performed. Findings suggest that this model is effective and sustainable, promotes and supports knowledge transfer and as such it can be recommended for implementation in other emerging rural destinations.

Part IV New Approaches

Measuring the quality of destinations: a portuguese case study.

Research on the quality of destinations has been developed from the tourists’ perspective, and a more holistic view is necessary for integrated destination planning. This implies cooperation among multiple stakeholders and the sustainable use of resources. The purpose of this study is to establish a conceptual model to measure the quality of destinations, considering the concepts of governance, sustainability, and tourist experience. According to the index, that used data from Algarve region, the performance of a destination depends on these three main dimensions, each one measured by a set of subdimensions that were weighted by an international expert panel. The result provides guidelines for transfer of knowledge to the main destination stakeholders.

Social Media and Knowledge Transfer in Tourism: Five-Star Hotels in Philadelphia

An essential part of the transfer of knowledge in the tourism and hospitality industry, destination image is defined as the expression of objective knowledge, imagination, and the subjective emotions of the tourist. Social media is profoundly changing the way the tourist images and interacts with the destination environment. In turn, firms in the industry are seeking to leverage the power of social media to gain insights into tourist cognition and behavior. In this chapter, we analyze various social media to investigate knowledge transfer relating to two groups of hotels in Philadelphia, and we propose a methodology to predict future lodging demand from empirical data in line with the objectives of the t-Forum.

Art, Architecture and Archaeology: Pompeii and Oplontis

Conserving, creating, and communicating effectively the complex image of a particular touristic area represents an important challenge that global market imposes on planners. Art and architecture can contribute to this challenge as they provide significant interactions and transactions among different sectors. Planning able to valorize patrimony and to read and to interpret cultural heritage is needed. New ways of collaboration need to be established among different fields of science, in order to develop, communicate, and experiment with a new language aimed at people from different backgrounds. The main theme in the “Archaeology and Synesthesy” project is to devise new method for the bringing to life of cultural heritage through participants’ senses.

Knowledge Transfer Through Journals

In order to facilitate transfer of knowledge to and within tourism, it is necessary to understand research trends and to critically analyze their contributions to knowledge formation. This chapter examine articles published in Annals of Tourism Research, Journal of Travel Research, Tourism Management , and Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , between 2000 and 2010, using STATIS to explore the main changes and trends that occurred in terms of research themes. Study findings indicate similarities and differences between the four journals under analysis, providing clues for a better understanding of the objectives, limitations, and trends in tourism research as well as the positioning of each academic journal.

Tourism Distribution Channels: Knowledge Requirements

This chapter presents a summary of the presentations and the discussions concerning electronic distribution channels in tourism and hospitality held at the 2015 t-Forum. Both academics and practitioners examined the present situation and elaborated on the problems and possible ways to overcome them. The main topics that emerged were distribution channels and their best use and optimization, interoperability between the many different technological systems, the need for a standardized representation of data and transactions, and the role of the Internet and Web as source of information useful for market analysis and product planning. Finally, the importance and the necessity of a more intense collaboration among all the stakeholders and between academic researchers and the industry was emphasized.

Part V Conclusion

Bridging theory and practice: lessons and directions, about the authors.

- Marcella De Martino

- Mathilda Van Niekerk

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Knowledge Management

Role of Knowledge Management System in Hospitality and Tourism Industry

Knowledge Management (KM) has established itself as a key part of many organizations, the process of creating value from an organization’s intangible assets. It deals with how best to leverage knowledge internally in the organization and externally to the customers and stakeholders. The growth of world markets, availability of technology and management know-how, the political and economic integration worldwide has led to increased globalization of hotel industry, hence the need to manage knowledge. Globalization of business has made it critically vital for organizations to adopt knowledge management as a strategy to build sustainability and improve customer services in the hotel industry.

The hospitality system mainly consists of the following areas, which cooperate/network but also compete with each other:

- Tour Operator

- Incoming System

- Regional and National Tourism Organisations

The tourism industry is a knowledge-based industry. Like in every organisation, the hospitality industry has a clear information overflow, hard for clients to pick the right holiday package available from numerous travel agents at similar prices. Lots of products and services, information and market partners are available. A big advantage for tourists is the freedom of choice and for tourism providers a variety of partners being available. But both tourists and travel partners have the task of evaluation to fulfil i.e. who has the best and nicest product, who really offers what comes close to the customers’ wishes and needs?

The nature of tourism products and services are human beings providing the guest a “moment of truth”, special experiences and a warm and charming feeling they should not forget quickly after their holiday. The knowledge intensity in tourism processes is the increasing importance of trust in relations between the acting elements. According to Bouncken/Pyo, there are three forms of trust:

- Personal Trust (the trusted is an individual)

- Institutional Trust (the trusted is an institution)

- Ontological trust (the reliance on one’s own cognitive maps, built up by experience)

In the tourism industry, the knowledge intensive services and relations need trust building over time. Trust as being part of the implicit knowledge of persons and organisations is a core competence in this industry. Sources of trust can be, for example, the reputations of travel agencies, suppliers and the personal recommendation by trusted friends, colleagues, and partners.

Categories of Knowledge in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry

Different categories of knowledge can be found when looking at the various jobs and employees working in the tourism field:

Task Specific knowledge

Task specific knowledge contains the specific procedures, sequences, actions and strategies to fulfil a task. Both explicit and tacit knowledge is used to fulfil companies’ goals. Examples are front and back office operations which are codified in manuals but also need to be learned by training. The way call center employees talk to guests, give them information; manuals help with used phrases but on-the-job training is necessary to internalise the knowledge. Therefore, to store all the agent training related materials and documents, deployment of a centralised repository such as PHPKB is mandatory in an hospitality organization.

Task Related Knowledge

Task-related knowledge contains individuals’ shared knowledge not of a single task, but of related tasks, e.g. the form of teamwork in the firm. Not a single task but the network thinking of different tasks and how they are combined and intertwined help a team/group of employees to internalize similar working values. Examples of task-related knowledge are shared quality standards, standardized products, and services used in different offices of one company e.g. layout of bills, guest requests, offers to clients, and corporate culture components.

Transactive Memory

Transactive memory includes decentralized knowledge of the other organizational members’ cognitive models. The main understanding of this form of knowledge category is the realization of each other’s knowledge, preferences, weaknesses, and work values. Examples are yellow pages (finding the right expert for a certain knowledge needed).

Guest Related Knowledge

Tourism products and services are formed around their customers; therefore, the knowledge about guests is the core of the business. Examples are socio-demographics, preferences, expectations, culture, etc. Knowledge about guests should not only be based on demographic information such as age, income, education, status or type of occupation, region of the country, and household size but also on psychographics that includes people’s lifestyles and behaviors; where they like to go on holidays, the kinds of interests they have, the values they hold and how they behave. A deeper understanding of the traits of guests will help to provide the right package that better suits their needs.

Customer/Supplier Related Knowledge

This knowledge is basically treated the same way as the guest-related knowledge; the difference here is to look from a business perspective towards the customers and suppliers (e.g. regional tourist offices, hotel chains, tourism consulting companies, event management companies, catering companies, etc.)

Market-Related Knowledge

Market-related know-how such as size, population, culture, and habits are important for every organization. The operating markets might vary enormously to the key market and the offered products and services will have to change and need to be adapted accordingly.

Network Related Knowledge

The organization should understand what kind of network it is operating, and who are the competitors. This externally linked knowledge is sometimes underestimated but is very important for the long-term success of an organization. Especially in the tourism and leisure industry, relationships with other players are extremely important. These knowledge elements help a national tourism organization to better market and offer different products and services to their customers and position itself on the market.

The management of customer relationships and experiences is also part of the knowledge management concept. Customer relationship management and customer experience management are a crucial part of every company’s way of doing business (consciously or unconsciously performed). The root of these management techniques is the single customer being the key to performance success or failure. Knowledge management has the following main purposes and is implemented as:

- Networking of experts

- Document management

- Create new products and services

- Enhancement of customer and employee satisfaction

- Enhancement of innovation and competitiveness

- Enhancement of processes

- Development of competences

- Development of a knowledge friendly company culture

- Enhancement of communication channels within the organization

Hospitality Knowledge Management and Customer Experience

The travel and hospitality industry is extremely competitive, and margins are thin. Still, travelers demand great customer experiences. Delivering personalized customer service increasingly relies upon knowledge management for travel and hospitality companies. Your customers’ problems are resolved quickly across each interaction, which is critical for market growth.

With ever-increasing competition in the travel and tourism industry, it has become crucial for companies to utilize knowledge management and provide levels of customer service that surpass all previous standards in order to gain the upper hand when securing business from potential holidaymakers and travelers. Along with the increasing competition, the number of customers booking online has seen sharp growth over the last decade leading to the need to devise strategies in which these increasing demands can be managed.

People don’t want to book their long-awaited holidays through travel agents; customers have access to a broad range of companies and travel options at the click of a mouse online. As a result of this customer contact centers are becoming more and more stifled with vast volumes of customer queries, be it a pre-sale or post-sale inquiry requiring agents to possess unprecedented levels of travel knowledge. Therefore, additional tools must be implemented for agents to achieve their full productivity potential.

The solution for managing these continually rising demands is knowledge management software , enabling the customer to self-serve and empowering the agent with fast access to an extensive resource of accurate knowledge.

Knowledge Management Software as Self-service Tool

Customers expect easy resolutions to issues via the internet, and in particular over mobile devices. They want to choose their preferred method of communication, including solutions that circumvent the live agent. Knowledge Management software is an ideal solution to not only reduce the volume of support-related calls to contact centers but also as an answer to reduce call escalations by significantly improving first-call resolution rates. This allows your agents the time to address more complex customer queries and provide the levels of customer service paramount to your company’s reputation.

The above resolutions to modern-day travel and tourism challenges not only provide cost-saving measures to your hospitality company but also add an abundant value to improving customer satisfaction and experience, by greatly reducing the time taken to find accurate answers, as well as providing exceptional customer-friendly self-service channels.

PHPKB knowledge management system helps you create innovative, distinctive customer interaction hubs with knowledge management for travel and hospitality with such options as collaboration through forums and emails, and web self-service through an effective knowledge base. One of the most important steps when implementing a new knowledge base software to build a perfect knowledge base is to create a well-designed plan and then launch it systematically.

Knowledge Management Software as Agent’s Support Assistant

A quick deploy knowledge management system reduces the wastage of time spent flicking through large numbers of company documents and PDF files. In place of this time-consuming process, customer service agents can effortlessly span an entire library of documents using a natural language search feature, providing results almost instantaneously. PHPKB knowledge management software can help you organize all customer-related knowledge and thus reduces the support cost.

Find out how PHPKB knowledge management software can help you to provide the best self-service experience to your users so they can easily find what they need. Get a privately hosted 30-day trial to take a deeper dive into PHPKB!

The type and volume of customer queries can vary significantly depending upon the event or competitive offers. Knowledge management for travel and hospitality can support spikes in a volume created by events and special promotions. It will enable your company to receive alerts to potential interruptions in customer service, closely monitor trends, and disseminate responses across many channels.

20 people found this article helpful what about you?

Leave your email if you would like additional information.

- Post Comment

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Managing Knowledge in Tourism Industry: A Nonaka's SECI Model

2022, IJMRAP

With the uncertainty in the environment, most sectors have experienced the significance of knowledge creation and sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism is one of the most affected sectors during the pandemic, searching for knowledge creation and sharing to cater to tourism business dynamics. Nonaka's SECI model has been used for creating and sharing knowledge since its introduced in 1995. The Japanese concept of the shared commonplace, known as "ba", is crucial for this spiral process of SECI. The "ba" could play a significant role in Socialization and Externalization in the SECI model. This study aims to explore the adoption of the SECI model for knowledge creation and sharing, in the recent past study, exclusively in tourism-related studies. Therefore, fifty empirical studies in the last ten years were used for this study. SECI model has contributed to transferring intangible knowledge into valuable knowledge assets in the tourism industry in various countries by promoting and sustaining it in the tourism business. The study found that previous studies have hardly discussed the importance of the "ba" concept.

Related Papers

João Filipe Marques

Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo

Marcelo Henrique Otowicz , Leonardo Lincoln Leite de Lacerda

When it comes to knowledge management (KM), one of the ways to classify it is through its processes. When it comes to tourism, it is the sectors that reveal its practical development. At this juncture, this article aims to analyze which are the tourism sectors that are considering KM in their research, as well as which KM processes are most used in tourism studies. To this end, this research is supported by an integrative literature review and follows the guidelines of the PRISMA recommendation. Due to the research protocol established and using the Scopus and Web of Science databases, an initial sample of 376 articles was obtained, of which 107 met the eligibility criteria. The research results are: (1) the most representative sectors are macro tourism and the accommodation services segment; (2) there is an emphasis on knowledge sharing and transfer processes, which are KM concerns also in other areas; (3) the researches highlight tacit knowledge, given its management complexity an...

Leonardo Lincoln Leite de Lacerda

International Journal of Hospitality Management

Tuba BUYUKBESE

Journal of Tourism Management Research

The Service Industries Journal

Sushmita Dela Peña

Tourism Review

Prof. Dr. Anita Zehrer

Journal of Knowledge Management

Birgit Muskat

Purpose-This study aims to explore and synthesize the role of knowledge management (KM) in tourism organizations (including micro, small, medium and large enterprises and destination management organizations). Design/methodology/approach-This study adopts systematic review methods to synthesize the role of KM in tourism from 90 journal articles. Findings-This study identifies the prominent theories adopted to explore the relation and impact of KM in the tourism sector, the geographic distribution of the literature and thorough qualitative synthesis. This study identifies the critical research themes investigated and the outcome of KM applications. Finally, through reviews, this study identifies critical gaps in the literature and offer promising avenues to advance the KM in tourism research. Originality/value-This is one of the few papers that comprehensively review the role of KM in the tourism industry and offer implications.

RELATED PAPERS

Molecular cell

Paul Doetsch

Diabetologia

Frank Naert

Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva

Rosangela Caetano

performanceparadigm.net

edward scheer

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing

NS. CUT HUSNA, S.KEP.,MNS

Cerebral Cortex

JULIAN GONZALEZ

Sudhakar Radhakrishnan

Vietnam Journal of Biotechnology

Leprosy Review

Ketsela Desta

SSRN Electronic Journal

Juan Carlos López Cabañas

JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute

Louise Ryan

BMC Research Notes

Martine Etoga

Maria Isabel Molina

Mathieu Corp

Etienne Montero

Dante Bartoli

Transplantation proceedings

Marcelo Perosa

Dorothee Chouitem

British Journal of Ophthalmology

Harold Hammer

Revista Digital Constituição e Garantia de Direitos

Marcello Borges

Carlos Vergara alonso

utgrr efdddsa

Acta Scientiae Veterinariae

Aline Delfini

Le Coq héron

Francis Martens

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

- PMC10447968

The perceived value of local knowledge tourism: dimension identification and scale development

Hailin zhang.

1 Department of Tourism Management, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

2 ASEAN Tourism Research Base, Guilin Tourism University, Guilin, China

Jinbo Jiang

Jinsheng (jason) zhu, associated data.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Introduction

Local knowledge tourism encompasses the rich cultural heritage, historical narratives, and traditional practices of a specific destination. Despite its significance in enhancing the tourist experience, there is a dearth of research examining the subjective perceptions and values of visitors engaging in local knowledge tourism. Consequently, there is a pressing need to explore the composition of perceived tourist values in this unique context.

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, a constructivist grounded theory and content analysis are applied to analyze the data.

This study identifies and conceptualizes five distinct dimensions of perceived values in local knowledge tourism: functional value, emotional value, social value, cognitive value, and self-actualization value. Furthermore, an 18-item scale is developed to measure these dimensions quantitatively.

This research makes several significant contributions: (1) it expands the scope of perceived value research within the tourism domain and enhances our understanding of the tourist experience in local knowledge tourism; (2) it provides a reliable instrument for future quantitative investigations into the behavior and mindset of local knowledge tourists; and (3) it offers theoretical foundations and practical insights for destination managers seeking to develop tourism products tailored to the preferences and expectations of local knowledge tourists.

Local knowledge refers to the traditional knowledge, values, skills, beliefs, and philosophy that communities have developed through long-term interactions with their natural and cultural environments ( Lenzerini, 2011 ). This diverse and valuable knowledge has profound social, cultural, ecological, scientific, and economic significance, reflecting the rich diversity of human civilization ( Hill et al., 2020 ). Local knowledge is increasingly recognized as a significant tourist attraction and plays a crucial role in product development within the tourism industry ( Gato et al., 2022 ). To address sustainability and social justice in the tourist industry, it is essential to recognize the diversity of cultures and the inherent multifaceted modalities of knowledge. However, there is a need to further explore and understand the structure, characteristics, and assessment of perceived value in the context of local knowledge tourism to promote sustainability and social justice in the tourism sector ( Ramos, 2015 ). Local knowledge tourism is developed focusing on the elements of knowledge in heritage tourism and to facilitate dialogue and exchange between diverse cultures ( Moayerian et al., 2022 ). As such, it is a constructive response to the need of strengthening tourist experience in the era of cultural and tourism integration ( Yuan et al., 2022 ). Unlike heritage tourism which merely promotes superficial historical landscape viewing and experience, local knowledge tourism stresses in-depth visitor participation and knowledge development. Existing research has not given sufficient attention to visitors’ subjective impression and experience of an attraction’s worth in local knowledge tourism, and the structure, features, and assessment of perceived value must be elucidated.

The definition of perceived tourist value is derived from the marketing concept of customer values and was reintroduced into tourism studies in the 1990s ( Overstreet, 1993 ). Since the dawn of the 21st century, the concept has been extended to tourist consumer behavior and destination marketing research. It has also emerged as a new prominent research topic, following in the footsteps of quality management and visitor satisfaction ( Li et al., 2009 ; Zhu et al., 2021 ). This notion offers a perfect vantage point from which to comprehend the tourists’ all-encompassing assessments of their travel experiences within the framework of the consumption-based model of local knowledge tourism. The investigation of tourist perceived values will contribute to a deeper comprehension of tourist behavioral characteristics, consumption behavior, and consumption psychology, thereby furnishing a theoretical foundation for the development of products and a marketing strategy for local knowledge tourism.

And thus, the current research aims to address this gap and highlight the significance of local knowledge in enhancing the tourist experience. The current research intended to address the questions as follows, (1) What are the key components and dimensions of perceived value in local knowledge tourism? (2) How does the perceived value of local knowledge tourism contribute to sustainable tourism development and social justice? (3) What fundamental dimensions and scales can be implemented to enhance and promote the perceived value of local knowledge tourism? This exploratory research, conducted in the context of Guilin, China, employs a grounded theory approach to identify the multidimensional structure of perceived value in local knowledge tourism and develop a rigorous scale. By applying a stringent scientific procedure, this study aims to provide theoretical support and practical guidance for the development of local knowledge tourism, addressing a gap in the existing literature.

The paper is structured as follows: the introduction provides an overview of the significance of local knowledge tourism and the importance of perceived value. The literature review delves into the concepts of local knowledge, perceived value, and their relevance to the tourism industry. The methodology section describes the case study approach and the grounded theory utilized to identify the structure of perceived value in local knowledge tourism. The findings and analysis section present the results of the study, including the multidimensional structure and components of perceived value. The discussion section interprets the findings, highlighting their theoretical and practical implications. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the key insights and suggests future research directions in local knowledge tourism and perceived value.

Literature review

The theory of local knowledge.

Geertz (1974 , p. 19), an American anthropologist, is attributed with introducing the idea of “local knowledge” as a central notion in interpretative anthropology; nevertheless, he did not provide a precise term for the concept. Local knowledge has been characterized in a variety of ways, depending on the setting and the goals of various researchers and organizations. For instance, the United Nations’ Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems Program (LINKS), which aims to support the preservation and transmission of collective memory and cultural heritage, defines that understandings, capacities, and philosophies formed by communities with extensive histories of engagement with their natural environs are referred to as local knowledge ( UNESCO, 2017 ). Local knowledge plays an essential role in a cultural network that also includes linguistic systems, categorization schemes, techniques for making use of resources, social interactions, and rituals and spiritual activities. Local knowledge, on the other hand, is a form of peripheral and unofficial knowledge held by indigenous people. This stands in contrast to the universal scientific knowledge centered on the West. Broadly speaking, it is the sum of material and cultural achievements accumulated by people in a certain region during their historical development, involving every aspect of life that may include local economic development, science and technology, social values (SVs), religious beliefs, culture and arts, social customs, lifestyles, and social codes of conduct ( Correia et al., 2013 ; Lepore et al., 2021 ). It is not always related to specific daily life, but also contains abstract thoughts, philosophies, and insights, which are comprehensive knowledge and technology about ecology, geography, or society that revitalize the locale ( Gao and Wu, 2017 ; Zhu and Siriphon, 2019 ).

The theory of local knowledge tourism

Local knowledge can highlight the diversity and equality of different cultures (see Table 1 below). The mysterious local knowledge is inherently attractive to the general public, by which such knowledge is related to the cultural economy ( Zhang and Liu, 2012 ), festivals creation ( Chaiboonsr et al., 2022 ), coproduction of histories ( Glover, 2008 ), as well as ethnic tourism development issues ( Chatzopoulou et al., 2019 ). Integrating local knowledge into the design of participatory tourism can highly promote the quality of tourism development, participation of local community in tourism planning and operation, as well as heritage preservation ( Pongponrat, 2011 ; Pongponrat and Chantradoan, 2012 ; de Bruin and Jelinčić, 2016 ). Deep experience of local knowledge in a destination, for instance, local engagements ( Sofield et al., 2017 ; Rahmanita, 2018 ) and indigenous tourism experiences ( Butler, 2017 ) will contribute to the tourist experience and lead to in-depth tourism. A consensus has been reached that enhancing cultural integration and tourist experience in destination management has become a significant trend for tourism planning and products development ( Beritelli et al., 2007 ; Halkier, 2014 ; Pechlaner et al., 2015 ). Based on the above discussion, this study defined local knowledge tourism as a type of heritage tourism that utilize local knowledge of a destination as its essence of tourism attraction, aiming to conserve the traditional cultural heritage and provide an in-depth and participatory cultural tourism experience and knowledge acquisition opportunity to tourists. From the perspective of the tourist, one of the main goals or motivations is to gain local indigenous knowledge of the destination. Since local knowledge encompasses the knowledge and practices contextualized in the local daily life experiences, such tourist activities can offer a deeper cultural experience compared to other types of heritage tourism.

Scale examples of tourist perceived value.

Data source: this study.

The theory of tourist perceived value

Customer perceived value was first discussed in the field of marketing and refers to how customers feel about a product or service with regard to perceived quality, internal and external features of the product, and other psychological benefits ( Zeithaml, 1988 ). It has been defined as a customer’s assessment of the trade-offs between the benefits and sacrifices realized in selecting a given product from the options available in the market ( Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo, 2007 ; Lim, 2013 ; Behnam et al., 2023 ). Perceived costs consist of monetary costs and non-monetary costs such as costs of time, physical efforts or life style changes that one has to pay to acquire the product or service ( Snoj et al., 2004 ). As a special form of customer perceived value, tourist perceived value is the emotional and psychological benefits generated by a series of interaction between tourists and the outside world. It is an important research dimension to grasp tourists’ perception and experience of tourist destinations ( Bao and Xie, 2019 ). It is defined as the trade-off between perceived gains and losses of tourists in a specific tourism context and it is an overall evaluation of tourist products or services ( Luo et al., 2020 ; Zhu et al., 2023 ). Perceived value is deemed to have great impact on tourist preference, satisfaction, and loyalty, for example, high level of perceived value will lead to the repurchase of the products and service ( Chen and Chen, 2010 ). Therefore, measuring the perceived value of tourists may contribute to a better understanding of tourists’ consumption behavior and psychology, as well as provide theoretical basis for tourism marketing ( Biao et al., 2020 ). The circumstances, quality, and attributes of tourism products play a significant role in determining the tourist perceived value. Meanwhile, it is also influenced by subjective elements such as preference, attitude, physiological condition, demand, and motivation ( Woodruff, 1997 ; Zhang et al., 2018 ). Compared to consumption activities in other commercial sectors, tourist consumption is more complicated and diverse, and the perception of tourist worth has plural and structural dimensions. The perceived value of a tourist destination contains functional value (FV), hedonic value, and symbolic worth ( Xie and Li, 2009 ). Due to the intangible, diachronic, and interactive features of tourism products and services, tourists tend to perceive the value of tourism experiences from a holistic perspective considering multiple elements such as a product, service, and destination ( Huang and Huang, 2007 ).

Dimensions and measurement of tourist perceived value

Customers perceived value are mainly assessed in the unidimensional approach ( Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo, 2007 ) and the multidimensional approach ( Loureiro et al., 2012 ). The unidimensional approach emphasizes economic utility apart from the trade-offs between the benefits such as customer utility and sacrifices such as price, time, effort, etc. ( Bunghez, 2016 ; Yin et al., 2017 ). A typical practice is to incorporate the tourist perceived value as an independent variable into the model of tourist satisfaction or loyalty ( Chenini and Touaiti, 2018 ). To overcome the limitations of the unidimensional approach that ignores various aspects of a person’s emotional state and external conditions, the multidimensional approach was proposed to explore the factors underlying the phenomenon ( Sheth et al., 1991 ; Sweeney and Soutar, 2001 ). Using the multidimensional approach, Sheth et al. (1991) identified five dimensions of customer perceived value that include social, emotional, functional epistemic, and conditional value. Sweeney and Soutar (2001) synthesize previous studies (e.g., Groth, 1995 ; Grönroos, 1997 ; de Ruyter et al., 1998 ) to develop the four-dimension PERVAL scale in which the emotional value (EV), for example, represents the utility derived from the feelings or affective states that a product generates; and SV refers to the utility derived from the product’s ability to enhance social relationship.

To assess the tourist perceived values, scales have been modified and developed in different tourism contexts, such as the five-dimensional SERV-PERVAL scale that encompasses quality, monetary price, non-monetary price, reputation, and emotional response for cruise tourism ( Petrick, 2004 ). Andrades and Dimanche (2018) analyze tourist value perception from the perspective of psychology and developed a scale of co-creating tourists’ experiential value at tourist attractions. Furthermore, related scales may involve the overall perception of a tourist destination, ecotourism, traditional event tourism, and cruise tourism. These studies might expand our understanding of consumer value in tourism and serve as a reference for the current inquiry, which will provide a reliable tool for quantitative study in the context of local knowledge tourism.

Grounded theory analysis and value dimensions identification

Research methods.

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, constructivist grounded theory and content analysis are applied to analyze the data collected. Grounded theory is useful to develop theory based on the analysis of systematically collected data and through interaction with study participants ( Mills et al., 2006 ). To realize the ultimate goal of theoretical construction with high reliability and validity, further to the primary data from the semi-structured interviews, secondary data are extracted from sources like online travelogue and news report to form a triangle cross validation. In the text encoding and follow-up study, review and advice are also sought from a group of experts for item purification. In the verification part, SPSS26.0 and AMOS24.0 were used for confirmatory factor analysis, reliability and validity analysis, and competitive factor analysis.

Guilin city, China, is chosen as the study case because it is a world-famous tourist destination and a recognized national historical and cultural city, as designated by the Chinese central government. In addition, Guilin is home to a dozen ethnic minorities, including Zhuang, Dong, Miao, and Yao. With extensive natural, cultural, and tourist resources, Guilin tourism contains rich local knowledge in a variety of forms, from traditional agricultural lifestyle to genuine ethnic culture ( Zhu and Siriphon, 2019 ), making it an appropriate case study for this investigation.

Data collection

The first step is to solicit the views of the respondents regarding four aspects of their local knowledge tourism experience: tourism motivation, experience process, experience value perception, personal feelings, and gain. From March to May 2022, semi-structure interviews were conducted in five local knowledge tourism experience zones in Guilin: the East West Alley, Longsheng Terrace Field, Guangxi Ethnic Tourism Museum, West Street of Yangshuo, and venue of the Liusanjie Impression Show. Each interview lasted about 20–30 min, and the whole process was voice recorded with the permission of the interview participants. According to the selection criteria, the participants needed to have conducted a local knowledge tourism in Guilin as defined by this study. A total of 22 participants were recruited through snowball sampling and their demographic profile is shown in Table 2 .

Profile of the respondents ( N = 22).

Coding and identifying the value dimensions

Using a method known as thematic analysis, the data were then evaluated and examined. Using the professional qualitative research software NVivo 11.0 for data coding, the thematic analysis has identified 19 concepts and 5 dimension of the tourism perceived values of local knowledge, including the FV, EV, SV, cognitive value (CV), and self-actualization value (SAV) as shown in Tables 3 , ,4 4 .

Example of open coding of local knowledge tourism perceived value.

1 The stilt house is a traditional residence house for ethnic minority such as Zhuang, Yao, and Miao in southwest of China.

Results of axial coding and selective coding.

Scale development

Item design.

The initial scale items of this study were developed from multiple sources such as researchers, experts, and literature. Compared to the mere use of the inductive and deductive methods, the mixed method with multiple item sources will have a higher level of validity ( Zhu et al., 2022 ; Lyu et al., 2023 ). Based on the 19 subcategories defined by the grounded theory analysis and some well-accepted tourism perceived value scales, a total of 25 initial scale items were developed. Following Delphi method, experts from Guilin Culture and Tourism Bureau, Guangxi Ethnic Tourism Museum, and Guilin Tourism University were invited to review and purify the initials items on the principle of conciseness, completeness, and correctness. As a result, 6 items were deleted, and remaining items refined in wording. The number of items is consistent with those of the formal questionnaire.

The pilot survey to develop the scale

Investigation process and sample analysis.

The pilot survey questionnaire is divided into three parts. The first part of the questionnaire includes a brief description of the questionnaire and the concept of local knowledge tourism with examples and photos. The second part is the five-dimension measurement adopting the 5-level Likert scale with “1” meaning “strongly disagree” and “5” meaning “strongly agree.” The third part addresses the personal information of the correspondent. According to Klein et al. (1994) , the sample size should be 10–20 times the number of measured items. The pilot study was carried out online between April and May 2022 to reduce the hazards associated with person-to-person interaction in COVID-19. A key recruitment requirement for respondents is that they must have a local knowledge tourism experience as defined by this study in Guilin within the last 12 months. To ensure the reliability and validity, questionnaires that took less than 120 s to complete and all choice are the same are deemed to be invalid. As such, 183, or 87.6% of the valid questionnaires were finally collected out of the total 209 distributed.

As shown in Table 5 , 56.8% of the respondents are female. A total of 82.5% are 21–60 years old, while those below 20 and above 61 accounted for 5.5 and 2.2%, respectively. As for occupations, civil servants represent 22.4%, followed by staff members in cultural, education, science and technology sectors (18.0%), enterprise employees (13.1%), and students (17.5%). Regarding education background, 50.8% are college/undergraduate students. To sum up, the demographic characteristics of the pilot survey respondents are basically in line with the real situation of local knowledge tourists.

Profile of the pilot survey respondents ( N = 183).

Descriptive statistical analysis

As illustrated in Table 6 , the mean values of FV, EV, SV, CV, and SAV were 4.30, 4.04, 4.15, 4.19, and 3.16, respectively. Although the score of SAV was relatively low as compared to other value dimensions, which can be explained by the classic theory of Maslow’s needs hierarchy. Self-actualization lies at the top of the hierarchy of needs; hence, it is the most complex and difficult to attain. Secondly, the kurtosis and skewness of data are used for testing whether samples are normally distributed, which indicates the universality of samples. The data skewness coefficient of each measurement element ranges between −1.903 and 0.156 with the absolute value smaller than 2, and the kurtosis coefficient is between −0.643 and 5.443 with the absolute value less than 8, which meet the criteria of normal distribution.

Descriptive statistical analysis of pilot survey ( N = 183).

Reliability test

The reliability of the questionnaire was tested by the internal consistency coefficient and the overall correlation coefficient of the item (CITC). The Cronbach’s α coefficient and CITC value of each variable were obtained by using SPSS24.0 for the items of five latent variables: FV, EV, SV, CV, and SAV. The results showed that Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.914, and of the five subscales were 0.767, 0.784, 0.826, 0.871, and 0.927 respectively, which are all acceptable. The CITC value of each item in the study also reaches the standard of 0.5. However, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was significantly increased after the fourth item of CV, i.e., “ I can better reflect on and recognize my own culture through local knowledge tourism experience ,” was deleted. To ensure the internal consistency of the questionnaire, it is therefore decided to delete the item. The author argues that the reason why the deleted fourth item of the CV dimension failed to meet the standard is because the respondents in the interview were all Chinese, they may not be able to distinguish between their own culture and that of the others in the case of Guilin.

Exploratory factor analysis

To investigate the underlying dimensions of the items, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with a component analysis and the varimax rotation method. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO = 0.866) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ 2 = 5,860.12, df = 528; p < 0.001) indicated suitability to conduct the factor analysis. It was found that the remaining 18 items could be extracted into five dimensions, and the cumulative explained variance has reached 73.374%. The distribution of loading values for each factor after rotation was reported in Table 7 below.

Exploratory factor analysis of the pilot survey questionnaire ( N = 183).

Data source: this study. Highlights represent the items with loading value above 0.6, indicating good convergence validity, are combined to form a common factor.

After item CV4 has been deleted, the 18-item scale was finally formed. All factor loading is greater than 0.6 with most loading exceeding 0.7, which indicates that the samples have satisfactory convergence validity. The EFA results are basically consistent with the findings of the grounded theory coding, which preliminarily verifies that this newly developed local knowledge tourism perceived value scale has good reliability and validity.

The formal survey to validate the scale

The sample size was finally established at 400 by considering important factors such as the size of Guilin City, the number of measured items, and the time period in which the survey is conducted. The survey was carried out in a mixed way. The face-to face survey was done at five major scenic areas of Guilin, including the East and West Alley, Longsheng Rice Terraces, Guangxi Ethnic Tourism Museum, etc. And the Internet survey was conducted with the online survey firm Wenjuanxing (a survey software) from June to July 2022. A total of 456 questionnaires were collected, including 256 from the site and 200 from the internet. After excluding questionnaires with short filling time and consistent answers for all questions, 412 valid questionnaires were finally obtained, with an effective rate of 90.35%. The sample size has fully reached the standard and can be used for subsequent confirmatory data analysis following the suggestions by Hair (2009) . Only those who had a local knowledge tourism experience in Guilin over the last 12 months were invited for the survey. A total of 57.3% of the respondents were male and 93.7% are aged between 21 and 50, which indicates that young and middle-aged tourists show more interest in local knowledge tourism. Local knowledge tourism seems to be more popular among tourists with higher education background as 70.9% of the respondents had a college/university degree. This may be related to its knowledge-oriented attributes. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, 57% of the respondents were from Guangxi and the rest mainly from the neighboring provinces.

The descriptive statistical analysis of the formal survey suggests that the overall mean values of FV, EV, SV, CV, and SAV were 3.98, 3.80, 3.79, 3.92, and 3.45, respectively. The SAV score was still relatively low, but higher than 3.16 in the pilot surveys. The data skewness coefficient of each measurement element is between −0.931 and −0.022 with an absolute value less than 2, and the kurtosis coefficient is between −0.943 and 1.481 with an absolute value less than 8, which indicates that samples are normally distributed. The factor analysis suggested that the explained variance of the first factor without rotation was 27.410%, smaller than 40%, and there was no large amount of explained variance concentrated in one factor, indicating that the influence of the deviation of the common method was small and acceptable.

Reliability and validity tests