How global tourism can become more sustainable, inclusive and resilient

A sanitary mask lies on the ground at Frankfurt Airport Image: Reuters/Ralph Orlowski

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Ahmed Al-Khateeb

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

- Tourism rose to the forefront of the global agenda in 2020, due to the devastating impact of COVID-19

- Recovery will be driven by technology and innovation – specifically seamless travel solutions, but it will be long, uneven and slow

- Success hinges on international coordination and collaboration across the public and private sectors

Tourism was one of the sectors hit hardest by the global pandemic. 2020 was the worst year on record for international travel due to the global pandemic, with countries taking decisive action to protect their citizens, closing borders and halting international travel.

The result was a 74% decline in international visitor arrivals, equivalent to over $1 trillion revenue losses , and an estimated 62 million fewer jobs . The impact on international air travel has been even more severe with a 90% drop on 2019 , resulting in a potential $1.8 trillion loss. And while the economic impact is dire in itself, nearly 2.9 million lives have been lost in the pandemic.

The path to recovery will be long and slow

Countries now face the challenge of reopening borders to resume travel and commerce, while protecting their populations’ health. At its peak, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) reported in April 2020 that every country on earth had implemented some travel restriction , signalling the magnitude of the operation to restart travel.

Have you read?

Tourism industry experts fear long road to recovery, how we can prioritize sustainability in rebuilding tourism, covid-19 could set the global tourism industry back 20 years.

Consequently, the path to recovery will be long and slow. The resurgence of cases following the discovery of new variants towards the end of last year delivered another disappointing blow to the travel industry. Any pickup over the summer months was quashed following a second wave of lockdowns and border closures . Coupled with mixed progress in the roll-out of vaccination programs, I predict that we will not see a significant rebound in international travel until the middle of this year at best.

Others echo my fears. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) forecasts a 50.4% improvement on 2020 air travel demand, which would bring the industry to 50.6% of 2019 levels . However, a more pessimistic outlook based on the persistence of travel restrictions suggests that demand may only pick up by 13% this year, leaving the industry at 38% of 2019 levels. McKinsey & Company similarly predict that tourism expenditure may not return to pre-COVID-19 levels until 2024 .

How to enhance sustainability, inclusivity and resilience

Given its economic might – employing 330 million people, contributing 10% to global GDP before the pandemic, and predicted to create 100 million new jobs – restoring the travel and tourism sector to a position of strength is the utmost priority.

The Great Reset provides an opportunity to rethink how tourism is delivered and to enhance sustainability, inclusivity and resilience. We must also address the challenges – from climate change and “ overtourism ” to capacity constraints – that we faced before the pandemic, while embracing traveller preferences, as we rebuild.

A 2018 study found that global tourism accounted for 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions from 2009 to 2013 ; four times higher than previous estimates. Even more worryingly, this puts progress towards the Paris Agreement at risk – recovery efforts must centre around environmental sustainability.

Furthermore, according to a study on managing overcrowding, the top 20 most popular global destinations were predicted to add more international arrivals than the rest of the world combined by 2020 . While COVID-19 will have disrupted this trend, it is well known that consumers want to travel again, and we must address the issues associated with overcrowding, especially in nascent destinations, like Saudi Arabia.

The Great Reset is a chance to make sure that as we rebuild, we do it better.

Seamless solutions lie at the heart of travel recovery

Tourism has the potential to be an engine of economic recovery provided we work collaboratively to adopt a common approach to a safe and secure reopening process – and conversations on this are already underway.

Through the G20, which Saudi Arabia hosted in 2020, our discussions focused on how to leverage technology and innovation in response to the crisis, as well as how to restore traveller confidence and improve the passenger experience in the future .

At the global level, across the public and private sectors, the World Economic Forum is working with the Commons Project on the CommonPass framework , which will allow individuals to access lab results and vaccination records, and consent to having that information used to validate their COVID status. IATA is trialling the Travel Pass with airlines and governments , which seeks to be a global and standardized solution to validate and authenticate all country regulations regarding COVID-19 travel requirements.

The provision of solutions that minimize person-to-person contact responds to consumer wants, with IATA finding that 85% of travellers would feel safer with touchless processing . Furthermore, 44% said they would share personal data to enable this, up from 30% months prior , showing a growing trend for contactless travel processes.

Such solutions will be critical in coordinating the opening of international borders in a way that is safe, seamless and secure, while giving tourists the confidence to travel again.

Collaboration at the international level is critical

The availability of vaccines will make this easier, and we have commenced our vaccination programme in Saudi Arabia . But we need to ensure processes and protocols are aligned globally, and that we support countries with limited access to vaccinations to eliminate the threat of another resurgence. It is only when businesses and travellers have confidence in the systems that the sector will flourish again.

In an era of unprecedented data and ubiquitous intelligence, it is essential that organizations reimagine how they manage personal data and digital identities. By empowering individuals and offering them ways to control their own data, user-centric digital identities enable trusted physical and digital interactions – from government services or e-payments to health credentials, safe mobility or employment.

The World Economic Forum curates the Platform for Good Digital Identity to advance global digital identity activities that are collaborative and put the user interest at the center.

The Forum convenes public-private digital identity collaborations from travel, health, financial services in a global action and learning network – to understand common challenges and capture solutions useful to support current and future coalitions. Additionally, industry-specific models such as Known Traveller Digital Identity or decentralized identity models show that digital identity solutions respecting the individual are possible.

The approach taken by Saudi Arabia and its partners to establish consensus and build collaborative relationships internationally and between the public and private sectors, should serve as a model to be replicated so that we can maximize the tourism sector’s contribution to the global economic recovery, while ensuring that it becomes a driver of prosperity and social progress again.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Travel and Tourism .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How Japan is attracting digital nomads to shape local economies and innovation

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024

Turning tourism into development: Mitigating risks and leveraging heritage assets

Abeer Al Akel and Maimunah Mohd Sharif

February 15, 2024

Buses are key to fuelling Indian women's economic success. Here's why

Priya Singh

February 8, 2024

These are the world’s most powerful passports to have in 2024

Thea de Gallier

January 31, 2024

These are the world’s 9 most powerful passports in 2024

South Korea is launching a special visa for K-pop lovers

Browse Subjects

- TOURISM POLICY

- POLICY MAKING

- CASE STUDIES

Making tourism more sustainable - a guide for policy makers

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Tourism - Development - Sustainable - Global This guide defines what sustainability means in tourism, what are the effective approaches for developing strategies and policies for more sustainable tourism and the tools that would make the policies work on the ground. 005 MAK SEPTEMBER 8, 2023 BY ANONYMOUS Download PDF (2MB) PEIN Date Created Thu, 08/20/2020 - 16:52 PEIN Date Modified Thu, 08/20/2020 - 16:52 PEIN Notes For archive section Record id 83541 Publication Date 2005

Resource Library

Making Tourism More Sustainable: A guide for Policy Makers

Published by: UNEP & WTO, 2005

This guide defines what sustainability means in tourism, what are the effective approaches for developing strategies and policies for more sustainable tourism, and the tools that would make the policies work on the ground. It shows clearly that there is no ‘one-fits-all’ solution to address the question of sustainability in tourism development. It does, however, highlight one key universal message: to succeed in making tourism more sustainable it is crucial to work hand in hand with all relevant stakeholders, within and outside government.

Therefore, although the report is aimed mainly at governments, public authorities at all levels are encouraged to disseminate its contents to those private and non-governmental organisations that have an interest in ensuring the long-term success of the tourism sector, especially the wide range of tourism businesses and their trade associations.

- Programmes Consumer Information for SCP Sustainable Buildings and Construction Sustainable Food Systems Sustainable Lifestyles & Education Sustainable Public Procurement Sustainable Tourism

- Network Members Directory Organisations

Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide For Policy Makers

- Published on August 7, 2018

Actors involved:

Share your work on sustainable consumption and production, you might also be interested in.

Ore Sand: A Circular Economy Solution to the Mine Tailings and Global Sand Sustainability Crises

Project zero.

Textile Newsletter - March 2024 - Edition 42

Select a language.

Advertisement

Making tourism more sustainable: empirical evidence from EU member countries

- Open access

- Published: 26 December 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ani Trstenjak 1 ,

- Ivana Tomas Žiković ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9156-3479 1 &

- Saša Žiković 1

532 Accesses

Explore all metrics

We analyze the sustainability factors that are pertinent to the tourism industry by exploring the effects of economic, environmental and social determinants on sustainable value added (SVA) in a two-stage analysis on a sample of 27 EU countries for the 2013–2019 period. In the first stage, we determine the relative efficiency based on DEA. In the second stage, we use the obtained variables in a dynamic panel data analysis setup. Contrary to the omnipresent push for complete green and sustainable transformation we find that increased GHG emissions will lead to an initial increase in SVA as the tourism sector needs time and effort to transition from a resource-oriented to an environmental-oriented production process. Contrary to previous findings, we show that environmental policies are not effective and that environmental taxation-related policies and procedures need to be revised. Economic growth implies increased pollution as well as increased SVA, as it requires more inputs and thus consumes more natural resources. Because of this it is of utmost importance to pay more attention to the quality of economic development in order to mitigate negative environmental externalities in the tourism sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability

Paul Ekins & Dimitri Zenghelis

Impact of green finance on economic development and environmental quality: a study based on provincial panel data from China

Xiaoguang Zhou, Xinmeng Tang & Rui Zhang

Impact of economic growth, international trade, and FDI on sustainable development in developing countries

Hoàng Việt Nguyễn & Thanh Tú Phan

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decade, tourism has been one of the fastest-growing sectors and its impact on national economies is significant. Current policies and programs aim to improve the quality and efficiency of businesses by creating added value. One of the key elements to achieve these goals is the analysis of the future model of sustainable tourism development, as numerous studies point to increased energy consumption and, consequently, significant environmental impacts (OECD, 2020 ).

Over the last 30 years, various systems of indicators for sustainable tourism development have been developed (UNWTO, Eurostat, European Commission), etc. The basic model of value added (VA) is based solely on economic variables, while the extended model of sustainable value added (SVA) includes other environmental and social variables in addition to the economic variables. Quantitative measurement of business effects on sustainability includes a triple approach (the so-called triple bottom line). The analysis introduces the concept of sustainable value added (SVA) (Figge & Hahn, 2004 ), which is an extension of the basic business value-added model (VA). The concept of SVA represents economic growth that includes the cost of environmental and social resources in the economy. The entire paradigm is based on simultaneous efficiency achieved by taking into account the environmental and social impacts on the economy. The main objective is to produce a greater quantity of goods and services with a smaller amount of available inputs such as materials, water, electricity, and greenhouse gas emissions while achieving higher efficiency in the production process. According to Zolfani et al. ( 2015 ), tourism is a type of green industry and appropriate management can improve the ongoing economic development of countries. Research on sustainable tourism is based on local situations, and in future, sustainable tourism will change into a transnational issue. The transition to a low-carbon economy will result in structural changes and the creation of new services that can offset the costs of the economic transition, accelerating the rate of sustainable economic growth and development from an economic, environmental, and social standpoint (Trstenjak, 2020 ; Yacht Rent; 2021 ).

Unlike previous studies, we apply a new approach to examining sustainable development, using three different groups of indicators representing the economic, environmental (energy), and social pillars of sustainability. Accordingly, the aim of this paper is to investigate the impact of determinants from each pillar on sustainable value added (SVA) in the tourism sector through a two-stage analysis. In the first stage, nonparametric Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is used to determine the relative efficiency for each country in each year by using inputs from each pillar to identify efficient and inefficient countries in terms of sustainable development. In the second stage, a dynamic panel analysis is employed to examine the SVA by using the remaining economic, environmental, and social variables along with the obtained efficiency scores from the first stage that indicate the country’s efficiency. In order to promote higher use of renewable energy sources in the tourism sector and increase energy efficiency in terms of lower energy consumption and higher SVA, the impact of the share of renewable energy sources in total energy sources is also tested. Although sustainability determinants have been extensively studied in previous literature, to the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to analyze not only sustainability determinants but also whether there are significant differences in achieving sustainable growth in the tourism sector when it comes to countries with a higher share of renewable energy in total energy sources, as well as between efficient and inefficient countries. According to the above stated, the following main research questions are the key drivers for this study: Do the economic determinants have a positive and significant impact on SVA? Are countries with higher RES in total energy sources more successful in generating SVA? What effect do GHG emissions have over the transition period to a greener and more sustainable tourism sector?

Our research contributes to the neoclassical economic theory (neoclassical model), which ignores or undervalues ecological concern and its value, which is contrary to the economic theories of sustainable development (Ditlev-Simonsen, 2022 ). According to neo-classical economic theory, the economy is a closed system where labor and capital are inputs that produce output (i.e., economic growth, GDP…). Either more inputs are produced or they are of higher quality, which results in economic expansion. Energy-related inputs are often treated as intermediate inputs and are considered to have only indirect influence (Žiković et al., 2020 ). After the rolling oil crises in the’60 and ‘70 economists started formulating energy-dependent production functions that would include energy in the classical Cobb–Douglas production function (e.g., Tintner et al., 1974 , Berndt & Wood, 1979 ). The theoretical assumption of the energy-dependent Cobb–Douglas function is that all combinations of three variables ( K , L , and E ) are possible and they jointly determine the output of an economy. According to Ayres and Warr ( 2009 ), all three production factors are essential and therefore not substitutable, except at the margin. The multi-sector characteristics of each economy are determined by the limits of substitutability and characterized by inter-sectoral flows and interdependencies. The three variables act as complements to a certain extent. Stern ( 1997 ) points out that econometric studies come to varying conclusions regarding whether capital and energy are complements or substitutes (for more on this see e.g., Berndt, 1978 and Apostolakis, 1990 ). When looking at the relevant research on this topic it seems that they are both complements and substitutes. Capital and energy act as complements in the short run but as substitutes in the long-run but, thus being gross substitutes but net complements. Bearing in mind all of the mentioned limitations, an energy-dependent Cobb–Douglas production function is still more realistic than the standard two-factor model.

Even though today interdependence and causality between economic growth and energy consumption has become a stylized economic fact, the direction of this causality has not been clearly determined. There is a line of research arguing that energy is a crucial production input together with other two production factors (labor and capital). Energy is a necessary precondition for economic development and as such can present a limiting factor to economic growth (Gali & El-Sakka, 2004 ). Contrary to this it can be argued that since the cost of energy usually represents a relatively small portion of the GDP, it is unlikely to have a significant impact on it; this leads to a stance that there is a neutral impact of energy on economic growth. Research results vary a lot with some research papers concluding that causality runs from economic growth to energy consumption, while others find the opposite. A significant number of papers even find bidirectional causality. A very detailed overview of a great number of studies on this subject can be found in Payne ( 2010 ). Several research papers examined the causality between energy and output in a multivariate framework for the energy-dependent Cobb–Douglas production function. Ghali and El-Sakka ( 2004 ) start from a neo-classical one-sector production function with three inputs and report bi-directional causality between energy and economic output. Their results run contrary to the neo-classical assumption of neutrality of energy on economic growth. Soytas and Sari ( 2006 ) examine the same relationship between energy consumption and output in a three-factor Cobb–Douglas function for G-7 countries. Their results show long-run causality between energy and income, again running contrary to the neo-classical assumption. Stern ( 2000 ) reports the presence of cointegration between output, capital, labor and energy in the USA. Belke et al. ( 2011 ) examine the long-run relationship between energy consumption and real GDP for 25 OECD countries. In their approach, they made a distinction between common factors and idiosyncratic components using PCA which allowed them to distinguish between international and national drivers of the analyzed long-run relationship. They also find cointegration between common components indicating that international developments dominate the long-run relationship between energy consumption and GDP.

Similarly to Ditlev-Simonsen ( 2022 ), in our research, we use the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approach, which also measures the business performance in addition to financial performance. All relevant factors will be evaluated holistically in order to support and add to the current research trends in this area of interest. Our study contributes to the body of knowledge in a couple of ways. Firstly, we could not find a study that holistically examines the connection between sustainable value added and variables that affect sustainability in the tourism sector. The TBL framework is used to analyze and present the dynamic relationship between the sustainable value added in tourism and the economic, environmental, and social determinants of sustainability. Secondly, in contrast to past studies, our research considers the technical effectiveness and the use of renewable energy within the EU tourism industry. In light of the aforementioned research issues, we present the following research hypothesis with regards to the EU tourism industry:

After adjusting for environmental and social variables, fixed capital (FCE) and revenue (TPE) both have a positive and significant impact on SVA.

The PH1 hypothesis will be tested by looking at how fixed capital (FCE) and income (TPE) as economic variables affect the dynamics of SVA. Since fixed capital boosts technical advancement in the industry and improves production, which in turn leads to specialization, member countries with higher fixed assets per 1.000 employed in tourism are more likely to be able to use their assets to generate income and, as a result, generate a higher SVA. Additionally, higher fixed assets generate new employment opportunities thus boosting individual income as well as tourism revenues. Our results show that higher income per employee is actually a sign of increased worker productivity in the tourism industry, which ultimately results in a higher SVA.

SVA is positively and significantly impacted by the share of renewable energy sources (RES) in the total energy consumption.

The added value in tourism is higher in countries where RES makes up a larger portion of all energy sources. Additionally, a considerable and advantageous influence on the development of SVA was revealed by the variable displaying the proportion of RES in the overall energy sources. Countries with less need for conventional energy sources may be able to develop new employment opportunities associated with the usage of RES. This effect results in the creation of new jobs, which in turn raises productivity and SVA. For instance, compared to energy produced via conventional sources, energy produced through solar photovoltaic cells creates more jobs per unit of energy produced compared to traditional energy sources.

Investments, energy use, and social security costs all differ significantly between technically efficient and inefficient countries when it comes to creating SVA.

Based on the previous empirical research one can start from an assumption that there are statistically significant differences between member countries that are technically efficient and those that are technically inefficient when it comes to the added value of the sector. Previous studies make the assumption that technically advanced nations utilize natural resources more effectively than less developed countries, especially when it comes to renewable energy sources, which have a large positive impact on added value. By efficiently using environmental inputs, notably RES, which have a large positive impact on SVA, technically efficient countries use less energy per SVA than the EU average.

Economic and social development based on the sustainability concept has a lot of advantages, both in the present and in the future. If more sustainable decisions are not taken, we will not be able to protect our planet's ecosystems or carry on as we have done so far. It's conceivable that humanity will run out of fossil fuels, and ores, and many animal species will go extinct and the atmosphere will be permanently harmed if detrimental processes are continued without any changes. The idea of sustainable tourism is crucial for the sector because, even while it can boost a local community's economy and create opportunities for individuals working in the sector, tourism can also have destructing effects including resource overuse, the eviction of animal and plant species and harm to the local way of life. Increasing positive effects and decreasing adverse effects of tourism on a destination are the goals of sustainable tourism (Trafalgar, 2022 ).

The paper is divided in five sections. After the introduction, Sect. 2 provides the literature review of the efficiency and sustainability of tourism development, while Sect. 3 describes the data and the methodology. Section 4 elaborates on the obtained empirical results. Section 5 draws conclusions, formulates implications and recommendations for future research.

2 Research on the efficiency and sustainability of tourism development

Many authors investigated the influence of the efficiency of input use in the production process, as well as the process of creating value added in the tourism sector.

Dogan et al. ( 2015 ) in their study determined how CO 2 (carbon dioxide) emissions from the tourism industry may be broken down and studied, as well as how they have changed over time and which factor is more significant in determining emissions. For this, a decomposition method based on the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index was utilized in this study for five Portuguese tourist subsectors for the years 2000–2008. The tourism industry is generally the most significant consequence. Effects of energy mix, carbon intensity, and energy intensity also turned out to be significant.

For the top 10 most-visited countries, the study of Dogan et al. ( 2017 ) examines the effects of real GDP, renewable energy, and tourism on the amount of CO2 emissions. Using a variety of panel econometric techniques, they discover that real GDP and tourism increase the level of emissions while renewable energy reduces them. So, in order to raise public awareness of sustainable tourism, regulatory measures are required. Additionally, the use of clean technology and renewable energy in the tourism industry, as well as in the production of goods and services, contribute significantly to lower CO 2 emissions.

Further, using a sample of 30 Chinese provinces across a 9 year period, authors He et al. ( 2018 ) use five parameters, including total factor productivity, capital-energy ratio, labor-energy ratio, energy supply composition, and output composition, since those factors are responsible for changes in tourism's energy efficiency. The study's findings demonstrate that the tourism sector's energy efficiency is significantly lower and that the main component that will increase tourism's energy efficiency is total factor productivity. Since 2010, the capital-labor ratio has gradually surpassed total factor productivity as the element that has contributed most to the change in tourism energy efficiency and has thus emerged as the major impediment to further improvement in tourism energy efficiency.

In a sample of G20 members, Lu et al. ( 2019 ) look at the effects of renewable energy consumption, tourism investments, GDP per capita, the real effective exchange rate, and trade openness on both tourism revenues (total tourism contribution to GDP) and international visitor arrivals. The goals of the current paper are accomplished by using panel econometric approaches and annual data from 1995 to 2015. The panel completely modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS) estimations' results for the long-run elasticities indicating that expenditures in tourism and renewable energy consumption have a significant beneficial impact on both tourism earnings and visitor arrivals. These findings lead to the argument that encouraging renewable energy should be seen as the main driver of tourism development in the G20 countries.

Leitão et al. ( 2020 ) investigate the connection between economic growth, RES, tourism, trade openness, and CO 2 emissions in the EU-28. They report that trade openness and RES decreased CO 2 emissions. They also found a positive effect of economic growth on CO2 emissions and they report that tourism arrivals are negatively correlated with CO 2 emissions, indicating a possible shift in the sustainability practices of tourism in the EU.

Balsalobre-Lorente et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the CO2-neutralizing effects of economic growth, international tourism, RES promotion, and technological innovation in the context of five EU countries in the 1990–2015 period. They find the inverted U-shaped economic growth-CO2 emissions nexus and confirm the Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis. They also find that higher FDI inflows increase CO 2 emissions but on the other hand energy innovation moderates the influence of air transport (proxy they use for international tourism) on CO 2 emissions during the development stage of the tourism industry. RES promotion is found to decrease CO 2 emissions.

Jebli et al. ( 2020 ) examine the impact of greenhouse gas emissions, and economic growth on added value on a sample of 102 countries using the GMM method and the Granger causality test. Renewable energy sources have a negative impact on added value in more developed countries while Katircioglu et al. ( 2020 ) analyze the impact of the tourism sector on greenhouse gas emissions in Cyprus. The results indicate a significant impact of the tourism sector on environmental degradation and the authors point out the importance of using environmental indicators in analyzing sustainable development.

In their study, Salahodjaev et al. ( 2022 ) examine the connections between tourism, renewable energy, and CO2 emissions in the nations of Europe and Central Asia between 1990 and 2015. They are using the two-step GMM estimator discovering that renewable energy reduces carbon emissions while tourism has a favorable impact on CO2 emissions. For instance, CO2 per capita emissions fall by 4.1% when renewable electricity generation rises by 10 percentage points. Further, the study of Mester et al. ( 2023 ) looks at how the GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, trade openness index, and energy intensity index have changed throughout the course of the EU 27 from 1995 to 2019. It also looks at how these variables have changed over time in relation to the international tourist development index. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to create a composite tourist indicator on an international scale. Panel autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach and Dumitrescu–Hurlin causality test validate the long-term feedback relationship between the tourism development index and trade openness, the tourism development index and CO 2 emissions, the tourism development index and GDP, as well as the unilateral causality running from the tourism development index to energy efficiency.

Leitão et al. ( 2023 ) analyze the impacts of the environmental Kuznets curve on economic growth for Visegrad countries from 1990 to 2018. They find that economic growth is positively correlated with pollution emissions but that the squared income per capita is negatively impacted by carbon dioxide emissions. For the Visegrad countries, they find that energy consumption, foreign direct investments, and urban population are positively correlated with economic growth but increase carbon emissions. Balsalobre-Lorente et al. ( 2023 ) analyzed the relationship between CO 2 emissions per capita, economic complexity index, RES, and foreign direct investment for BRICS countries in the 1995 to 2020 period. They confirm the existence of the environmental Kuznets curve, with a positive but decreasing contribution of economic development on environmental deterioration. They also approximate the impact of the Industry 4.0 technologies on carbon emissions, finding some evidence that their effect on environmental deterioration is moderate thus showing the potential to achieve the neutrality of polluting emissions.

With mounting evidence of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas (GHG) accumulation throughout time, the use of taxes to promote a sustainable environment is becoming more and more crucial. The effectiveness of environmental taxes in reducing the impact of tourism on environmental performance in the EU-28 nations from 2002 to 2019 is assessed in this study by Usman and Alola ( 2022 ). The panel threshold regression model's empirical findings imply that the impact of tourism on environmental performance is influenced by the level of environmental taxes. Particularly, when environmental taxes are below the criterion level of 9.43%, the impact of tourism on environmental performance is negligible. Tourism would boost environmental performance though once environmental taxes reach a certain point. This shows that there is a considerable difference between periods of lower and higher environmental levies in the way that tourism affects environmental performance. As a result, our findings offer policymakers and other stakeholders new information about how to employ environmental taxes as a tool to prevent environmental degradation and, in turn, lessen global warming and other serious climate changes.

Another group of studies examined SVA in terms of the relative efficiency of countries using the DEA methodology. The authors found useful information about inefficient countries and areas where they could improve their efficiency. Kosmaczewska ( 2014 ) evaluated the relative efficiency of 27 EU countries using different DEA techniques. The results show that richer countries achieved higher technical efficiency, while poorer countries achieved higher scale efficiency (SE), which shows the possibility of improvement of efficiency through the change of scale of the phenomenon (or production). Toma ( 2014 ) applied the DEA model to assess the efficiency of the tourism sector at the regional level. He used numerous inputs (employees, firms, investments, and tourist destinations) and outputs (sales turnover, regional GDP, tourist overnight stays) variables. The results showed a lack of efficiency in regions with a higher number of tourist arrivals the need for intervention in the exploitation of scarce resources (labor, capital, and infrastructure), and the necessity of implementing real efficiency measures. Lozowicka ( 2020 ) monitored the efficiency of the implementation of the EU Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the period 2005–2015. The study showed that developed countries such as Austria, Finland, Sweden, Greece, and Slovenia achieved a higher level of efficiency in the implementation of sustainable goals in the tourism sector. Hermoso-Orzaes et al. ( 2020 ), on the other hand, point to the need to improve the environmental policies of less efficient member states. Soysal-Kurt ( 2017 ) measured the relative efficiency of 29 EU countries using input-oriented and constant returns to scale DEA. He proposed improvement for countries found to be inefficient based on their measured relative efficiency scores. Barisic and Cvetkovska ( 2017 ) identified countries in the EU 28 that use their resources efficiently and show the relative efficiency of their impact of travel and tourism on GDP and employment. The output-oriented BCC DEA model shows that member states Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Portugal, Romania and Spain are relatively efficient, while Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Sweden are identified as relatively inefficient, i.e., they invest more in tourism given that they benefit from it, in terms of tourism employment and its share of GDP.

The social aspects of sustainability in tourism, particularly the role of labor and individual workers, are often hidden, despite widespread recognition that insecurity is prevalent in the tourism labor market (Ioannides et al., 2018 ). The social science literature emphasizes the need to go beyond ecological and technical knowledge when educating for transformative action and sustainability. Sustainable tourism development focuses attention on employee knowledge, and awareness of the tourism destination including investment in human capital (Laws et al., 2011 ). Miasoid and Frolov ( 2005 ) recognize that stress, lack of incentives, job insecurity, and an insufficient number of employees have a negative impact on the quality of work in tourism. A brand-new theoretical framework that considers the proportion of women, education, social capital, and human capital is proposed by Dong and Khan ( 2023 ). Women's advancement in the tourism industry is equally crucial to society's progress toward civilization and that policies and incentives should be put in place to encourage and ensure their active participation. This will help the tourism business grow and thrive in a sustainable manner. Women are unable to fully realize their potential to contribute to the tourism industry because they often hold positions that pay less and have lower prestige. In order to achieve internationally recognized development, environmental, and human rights goals as well as raise the level of life for women and communities, it is imperative that women be encouraged to engage actively in the economy. More women's empowerment and gender equality will be advantageous to the tourism industry (UNWTO, 2023 ).

3 Research model, data description and methodology

The empirical study is conducted using the commonly used, but also some novel indicators for sustainable tourism development, where the major used indicators were presented earlier. The starting point for explaining the research model, data description, and methodology was defining the variables of interest and creating the model of tourism sustainability.

3.1 Formulation of the research model

The Interreg MEDITERRANEAN initiative employed a strategy created by the Kedge Business School in France. When investing in the growth and competitiveness of a sector, Kedge Business School ( 2018 ) has developed an approach that employs the methodology of innovation of the capacities of businesses, industries, and sectors to achieve sustainable growth and development (3-Pillar Business Model). The entire tourist industry can benefit from this concept, which was primarily created for the maritime tourism industry.

The formulation of the research model focuses on the development of a sustainability model based primarily on the economic model of business value added (VA) within the framework of business productivity and Cobb-production Douglas's function as one of the most frequently used productivity measures in theoretical and empirical research (e.g., Žiković et al., 2020 ). The efficiency of labor and capital as primary production resources form the foundation of the aggregate production function. Examination of the elasticity of the resources used forms the foundation for the analysis of inputs in the production process (Bleischwitz, 2010 ). The most widely used indicator of value added at the macroeconomic level is gross value added (GVA), which is a gage of output or economic growth.

3.2 Data description

The empirical analysis uses data from Eurostat for the 2013–2019 period and includes all categories of tourism activities and services for EU 27 member countries according to the NACE Rev. 2. classification. Our definition of the tourism sector specifically uses the following sectors: accommodation, food and beverage service activities, travel agencies, tour operators, and other reservation service and related activities. Model specifications examine the effects of variables within the economic, environmental, and social pillars in terms of their relative change or elasticity on SVA. The analysis was limited by the availability of data from the Eurostat database and by irregular updates of the data at the same time.

The economic pillar of sustainability refers to the variables of fixed capital, revenue, and investment, while the environmental (energy) pillar includes final energy consumption, environmental taxes, and greenhouse gas emissions. The number of female workers, the number of employees with tertiary education, and social security expenditures are social pillar variables. All variables are scaled by the number of employees (in thousands).

Fixed capital (FCE) is expected to increase labor productivity by making the sector more productive and efficient. A higher ratio of equipment per employee results in more products being produced at a faster pace. In terms of revenue (TPE), it is desirable to have as high a ratio as possible, since a higher ratio indicates higher productivity, which often translates into higher profits for the sector. It also indicates that the sector uses its resources (human capital) wisely. Investment (IPE) is important because higher investment increases production capacity and leads to higher sector productivity. Investment is critical to building a competitive tourism sector, as the rapid growth of tourism in many countries creates new challenges while providing new opportunities. Continued strong growth is putting pressure on existing infrastructure and increasing the need for additional investment. Investments in quality tourism should manage growth in a sustainable and inclusive manner, with appropriate levels of investment to maintain and improve existing tourism offerings and develop new products (OECD, 2020 ).

Energy consumption (EC) is the prerequisite for increasing the value added in the tourism sector. This also means that an energy shortage can have a negative impact on the value-added, employment, and income of the sector. Revenue from environmental taxes and charges (ET) can be used to reduce other taxes, providing both environmental improvements and positive economic outcomes. Environmental taxes serve as a key mechanism to promote sustainable development and play an important role in mitigating the negative externalities of pollution. The historical relationship between economic development and emissions growth shows that GHGs are directly linked to economic development. Although most developed countries demonstrate a declining trend in per capita emissions, they still produce more emissions than developing countries. However, development is leading to the introduction of new energy-saving and low-carbon technologies that are displacing the old, energy and carbon-intensive technologies. Considering all these factors, the relationship between SVA and GHGs is expected to still be positive and these results are consistent with the research (Chen et al., 2016 ; Statista, 2022 ). More precisely, Wei et al. ( 2016 ) indicate that developed countries contribute about 53–61% and developing countries about 39–47% to the increase in global GHGs.

A review of social indicators of development sustainability showed a significant research gap of empirical studies in the relevant field. As women contribute to the preservation of culture and the promotion of tourism, which ultimately benefits the tourism industry, the proportion of women in the total workforce (TFW) is expected to have a favorable impact on the value added movement in the tourism industry. Tertiary educated workers (TPTED) are defined as those who have completed the highest level of education. This includes both theoretical programs that lead to advanced research or high-skill occupations and more vocational programs that lead to the labor market. As globalization and technology continue to change the needs of labor markets worldwide, the demand for individuals with a broader knowledge base and more specialized skills continues to grow and they tend to be more productive with a positive impact on SVA. Social security costs (SSC) encourage investment in human capital, which is an important source of productivity gains, and is expected to have a positive impact on the sector's SVA. The main goal of social security is to reduce poverty and strengthen the resilience of poor and vulnerable workers through income-enhancing transfers. In developed countries, it is recognized that investments in social security have a positive impact on economic growth, i.e., social security as an investment in the economy. Social security favors sustainable economic growth, which is consistent with the research of Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), Lee and Chang ( 2006 ). According to their research, there is a strong causal relationship between social security spending and economic growth.

All of the analyzed variables were used and suggested by earlier studies. Fixed capital (FCE) was employed in research by (He et al., 2018 ; Bhattacharya & Kumar Dash, 2021 ; Riti et al., 2022 ) because it was anticipated to boost labor productivity by making the industry more productive and efficient. Fixed capital is regarded as one of the primary factors for producing SVA and is typically defined as the stock of tangible, durable fixed assets owned or used by resident firms for more than one year. A higher ratio of revenue per employee (TPE), used by (Dimitropoulos, 2018 ; Filipiak et al. 2020 ; Wira, 2021 ), results in more products being produced at a faster rate. In terms of revenue, it is desirable to have as high a ratio as possible, since a higher ratio indicates higher productivity, which often translates into higher profits for the sector. Investment (IPE) was part of research conducted by (Fauzel et al., 2017 ; Sokhanva, 2019 ; Arain, 2020 ). Increased investment boosts production capacity and boosts sector productivity, making investments crucial. Investment is essential to creating a competitive tourist industry because of the new opportunities and difficulties that come with the tourism industry's rapid growth in many countries. The demand for more investment is rising as current infrastructure is under pressure from robust expansion that is still ongoing. Investments in high-quality tourism should control growth in a way that is equitable and sustainable, with adequate levels of investment to uphold and enhance current tourism services and create new ones (OECD, 2020 ).

Energy consumption (EC) was employed by (He et al., 2018 ; Lu et al., 2019 ; Kumar Dash, 2021 ) in their analysis as a requirement for raising the value added in the tourism sector. Energy consumption represents the quantity of energy used by a specific economic activity, which also means that a scarcity of energy could have a detrimental effect on the sector's value-added, employment, and revenue. Environmental taxes and charges (ET) can be utilized to lower other taxes, resulting in both better environmental conditions and beneficial economic effects. Since environmental taxes serve as a fundamental instrument to promote sustainable development and play a significant role in minimizing the negative externalities of pollution, their significance was demonstrated by (Zhou, 2019 ; Asalos, 2019 ; Yunzhao, 2022 ) in their analysis. GHGs are directly correlated with economic development, as demonstrated by the historical relationship between economic expansion and emissions growth (Yang et al., 2019 ; Jebli et al., 2020 ; Riti et al., 2022 ).

There is a lack of available data when it comes to social indicators for the tourism sector for all EU 27 members. However, the tourism industry is known for its large share of informal labor-intensive work, such as extended working hours, low wages, lack of social support and discrimination against women. The social determinant of the share of women in the total labor force (TFW) is a variable that Araujo et al. ( 2021 ), Samad and Alharthi ( 2022 ), and Santos ( 2023 ) also use in their analysis. They also investigate how well companies implement social goals such as working conditions, health and safety, employee relations, diversity, human rights and community involvement is part of measuring social sustainability performance. Laws et al. ( 2011 ), Romão and Nijkamp ( 2019 ) and Kedge ( 2018 ) showed that tertiary educated workers (TPTED) are defined as those having completed the highest level of education. This includes both theoretical programs that lead to advanced research or high-skill occupations and more vocational programs that lead to the labor market. As globalization and technology continue to change the needs of labor markets worldwide, the demand for individuals with a broader knowledge base and more specialized skills continues to grow and they tend to be more productive with a positive impact on SVA. Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), Garca Mestanza et al. ( 2019 ), Lee and Chang ( 2006 ) used in their analysis social security costs (SSC) as a variable that promotes investment in human capital, which is a key driver of productivity growth and is anticipated to increase the sector's SVA. Social security's primary objective is to build the resilience of low-wage and disadvantaged workers by reducing their level of poverty through transfers that increase their income. Investments in social security are known to have a favorable effect on economic growth in developed countries, making social security crucial. According to research by Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), Lee and Chang ( 2006 ), social security promotes stable economic growth. They found that there is a clear causal relationship between social security spending and economic growth.

The share of RES in total energy consumption (RES_dum) is introduced to examine the impact of a continuous source of renewable energy on SVA. If a country has a share of RES in the total energy sources of at least 15%, then it is assigned the value 1, otherwise, the value is 0. Furthermore, a dummy variable that distinguishes between efficient and inefficient countries was introduced according to the technical efficiency results obtained from the DEA analysis (Efficient_dum). We also used Efficiency scores (DEA_score) as an independent variable of our model as a robustness check. All of the above variables are expected to have a positive impact on SVA. The definitions of the economic, environmental and social variables considered in the model estimation are presented in Table 1 . Footnote 1

3.3 Methodology

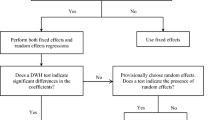

The effects of economic, environmental and social determinants on SVA were examined in a two-stage analysis. In the first stage, one indicator from each of the three pillars was used as input to determine the relative efficiency for each country in each year based on DEA. The obtained efficiency scores were used to create a new dummy variable indicating the relative efficiency of the countries in such a way that efficient countries have the value 1, while inefficient countries were assigned with a value of 0. The obtained variable was used in the second stage of the analysis along with new indicators from three pillars that were not part of the first stage analysis to avoid endogeneity problems. Since most of the variables exhibit dynamic behavior, dynamic panel data analysis with economic, environmental and social indicators was used in the second stage analysis.

3.3.1 Data envelopment analysis (DEA)

DEA is a nonparametric method used as the starting point for developing the research model. It is a method for measuring DMU (decision-making unit, i.e., country) efficiency using linear programming techniques, where multiple inputs and outputs can be considered simultaneously without assuming data distribution. In each case, efficiency is measured in terms of a proportional change in input or output. An efficient decision unit has a maximizing output for the same level of input values of production factors with respect to all observed decision-making units (output-oriented DMU) or a minimizing amount of input values of production factors for a given level of output values. The efficient production frontier is defined by a group of efficient DMUs, which is set as a benchmark of some combination of efficient DMUs (Batur et al., 2015 ).

In the DEA framework, a country or decision-making unit (DMU) that achieves an optimal value of 1 (100% relative efficiency) is on the efficiency frontier and is considered relatively efficient in the sense that its outputs cannot be increased further without increasing its inputs. Countries with an efficiency score bellow 1 are then considered relatively inefficient, suggesting that they can achieve a current output level with fewer inputs. Each country has a certain number of inputs ( i ) and outputs ( o ), meaning that it consumes a certain amount of inputs to achieve a certain output. DMU productivity can be written by the following equation:

where u and v are weights assigned to each input and output. Such that, u r and v i are the weights of inputs and outputs, respectively, y rj and x ij are the inputs ie outputs of the observed DMU.

Based on the scale and orientation of the model we used Charnes–Cooper–Rhodes (CCR) model (1978) that assumes a constant rate of substitution between inputs and outputs. SVA is an output variable of the model, while following variables were used as inputs in DEA framework: investments, energy consumption and social security costs. All variables are scaled with the number of employees (in thousands).

3.3.2 Generalized method of moments (GMM)

Since economic, environmental and social variables show dynamic behavior, the second stage of the analysis is carried out by using dynamic panel models. The most commonly used estimators in dynamic panel data analysis are the difference Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator proposed by Arellano and Bond ( 1991 ) and the system GMM estimator proposed by Arellano and Bover ( 1995 ) and Blundell and Bond ( 1998 ). GMM estimators obtain consistent and unbiased parameter estimation and resolve the endogeneity problem by including lags and differences of the endogenous variables as instruments.

The linear dynamic panel data model with explanatory variables and lagged dependent variable \({y}_{it-1}\) can be written as follows:

where i = 1,…N is the index for individuals (countries) and t = 1,…T is the index for periods (years). \({y}_{it}\) is the dependent variable (SVA for a country i in period t ), \({y}_{i,t-1}\) is the lagged dependent variable with parameter \(\gamma \) , the parameter \(\mu \) is the constant, \({X}_{it}\) are economic indicators that change across countries, \({Z}_{it}\) are environmental indicators, and \({W}_{it}\) are social indicators that also change across countries and time over countries and time. \(\beta , \lambda \) and \(\delta \) are parameter vectors estimated by a linear panel model. \({\alpha }_{i}\) is the individual effect or specific error for each country, while the remaining part of the error term \({\varepsilon }_{it }\sim N\left(0, {\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{2}\right)\) is normally distributed and assumed to be orthogonal to the exogenous variables and uncorrelated with the lagged dependent variable \({E({y}_{i,t-1}, \varepsilon }_{it })=0\) .

SVA exhibit dynamic behavior, i.e., current values of SVA depend on their past values. Problem arises with the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable as one of the explanatory variables due to a correlation between the part of the error term \({\alpha }_{i }\) and lagged dependent variable \({y}_{i,t-1}\) . To avoid this bias, Arellano and Bond suggested taking the first difference of the Eq. ( 2 ) as follows:

The individual effects are excluded from the differenced form of the equation. The instrumental variables (lagged values of dependent variable) are used to solve for the correlation between the difference lagged dependent variable and the difference error term. Instrumental variables are expected to be highly correlated with the difference lagged dependent variable, but at the same time they should be uncorrelated with the difference error term. When the dependent variable is highly persistent and when the ratio between the variance of the individual effect and the remaining part of the variance of the error term increases ( \({\sigma }_{\alpha }^{2}/{\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{2})\) , the difference (diff) GMM shows certain weaknesses. Therefore, Blundell and Bond ( 1998 ) have proposed a system (sys) GMM estimator that employs both the equation in first differences (3) and the equation in levels (2). Since the sys GMM estimator has better properties compared to the diff GMM estimator, the empirical analysis is performed using the sys GMM estimator. Another concern is the number of instruments that easily increase relative to the sample size. This problem is especially pronounced in small samples in which to many instruments can cause overfitting of the endogenous variables and fail to remove its endogenous components. This is solved by using PCA option for reducing the number of instruments (Roodman, 2009a , 2009b ). In addition, in line with Windmeijer ( 2005 ), the two-step system GMM is estimated with corrected standard errors and t -test statistics. Hansen test is employed to check the validity of the instrumental variables.

4 Empirical analysis

The DEA results from Table 3 (Appendix) show that of the 27 EU member countries, seven countries are technically efficient with respect to the following inputs from each pillar: investment, energy consumption, and social security costs. Germany and Austria have achieved technical efficiency in all observed years, while Denmark, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Spain have achieved technical efficiency in most of the observed years. The results show that inefficient member countries have insufficient investment and social security costs in the tourism sector. On the other hand, efficient member countries have lower energy consumption and higher levels of investment and social security costs per 1000 employees. Inefficient member countries have a deficiency in two inputs and a surplus in one input compared to the output, while efficient countries have the highest performance and maximum efficiency compared to the other member countries.

The DEA results were used to construct a new dummy variable indicating efficient and inefficient countries in terms of their sustainable value added. This variable was used as one of the control variables in the dynamic panel data analysis. The results of the two-step Blundell and Bond System GMM estimator are presented in Table 2 . First, we examine the SVA determinants from each pillar separately (Models 1, 2 and 3). Then, Model 4 is derived by taking determinants from economic, environmental, and social pillar together. Model 5 includes variables from all pillars and DEA_score. Model 6 includes variables from all pillars and two dummy variables: one for the share of renewable energy in total energy sources and one for the country's efficiency. Finally, Model 7 includes variables from all pillars, DEA_score, and two dummy variables (Table 2 .)

All model specifications presented have satisfactory diagnostic statistics. The null hypothesis of the Hansen test for overidentification of restrictions assumes that all selected instrumental variables are valid. The Hansen test in all model specifications confirms the validity of the chosen instruments. In addition, the presence of autocorrelation in the differenced residuals is tested using tests for the second-order serial correlation—AR (2). First-order autocorrelation is expected, while the presence of second or higher-order autocorrelation indicates that the model estimates are inconsistent. The last row in Table 2 shows that the null hypothesis on the absence of a second-order serial correlation-AR (2) is not rejected, indicating that the model estimates are consistent.

The results show that the lagged dependent variable is statistically significant and positive in all model specifications. This implies that the previous value of sustainable value added has a positive effect on the present value of sustainable value added in the tourism sector, which is consistent with the research of Kong et al. ( 2016 ), who concluded that the previous year's growth has accumulating effect on current year economic growth. Majed and Mazhar ( 2021 ) also found that high SVA in the past provides the opportunity for achieving higher SVA in the future. Dynamic effects of tourism and its uncertainty on economic growth in a global framework for different income groups are the main reasons why we use the lag of the dependent variable as an independent since the previous year’s growth has a leading effect on the current year.

The first three models show the impact of representative determinants from each pillar on SVA in the tourism sector. Fixed capital (FCE) is not statistically significant, while revenue (TPE) has a positive and significant impact on SVA, which is in line with previous research (Jebli et al., 2020 ; Katircioglu, 2020 ; Yang, 2019 ; Lu et al. 2019 ; Balli, 2018 ; Dogan et al. 2017 ). Moreover, both economic indicators, fixed capital (FCE) and revenue (TPE) are significant and have the expected signs when controlling for environmental and social determinants, DEA_score, and when including variables in the model specification indicating countries with a higher share of renewable energy sources in total energy sources, as well as dummy variables for technically efficient countries. Higher fixed capital in the tourism sector suggests that countries with higher fixed assets in the tourism sector are more likely to be able to use their assets to generate revenue and, consequently, to generate higher SVA in line with Majeed and Mazhar ( 2020 ) and Kostakis ( 2020 ). For instance, it increases the technical progress in the sector and enhances production, which in turn leads to specialization. It also creates new employment opportunities that increase not only the income of individuals but also the income of the sector. In assessing the relationship between revenue and SVA, the results show that higher revenue indicates higher productivity of workers in the tourism sector, which consequently leads to higher SVA. It also indicates that countries with higher revenues use their resources wisely, i.e., investing in employees leads to an increase in their productivity in line with Inchausti Sintes et al. ( 2020 ).

Increased GHG emissions will lead to an initial increase in SVA as the tourism sector transitions from a resource-oriented to an environmental-oriented production process. However, the environmental damage will gradually decrease, consistent with Katircioglu et al. ( 2020 ) and Robaina-Alves et al. ( 2016 ). GHG emissions have a positive and significant impact on SVA in all model specifications, which is in accordance with the conclusions of Kratena and Sommer ( 2014 ) and Yang et al. ( 2019 ). The results indicate that GHG emissions positively contribute to SVA, which may affect the quality of economic development. Economic growth implies increased pollution due to increased SVA, as it requires more inputs and thus consumes more natural resources. Hence, it is of utmost importance to pay more attention to the quality of economic development in order to mitigate negative environmental externalities in the tourism sector. This is also supported by the findings that environmental taxes and charges do not have a significant impact on SVA which is in line with the conclusions of Hinterberger et al. ( 2013 ) and SERI ( 2019 ). Reduced efficiency of environmental policies indicates the necessity of revising policies and measures and applying the new environmental economic instrument to ensure sustainable economic development in the tourism sector. According to SERI ( 2019 ), a combination of taxation, recycling, and advisory policies can stimulate the value added to the tourism sector. Further, the variable indicating the share of RES in total energy sources showed a significant and positive impact on generating SVA. Countries with a reduced need for conventional energy sources can create new employment opportunities related to the use of RES which is in accordance with the conclusions Dziuba ( 2016 ), Bohdanowicz et al. ( 2011 ), Jebli et al. ( 2020 ), Lu et al. ( 2019 ), Ntanos et al. ( 2018 ). RES has already demonstrated a job creation effect. For example, energy created through solar photovoltaic cells has a higher number of jobs created per unit of energy produced than energy produced through conventional sources. The positive job creation effect of RES is a result of longer and more diverse supply chains, higher labor intensity, and increased net profit margins (International Labour Organisation, 2022 ).

None of the social variables (TFW and TPTED) proved to be statistically significant in any of the model specifications. Some of the previous findings (Ioannides et al., 2018 ; Frisk & Larson, 2011 , Laws et al., 2011 ; Miasoid & Frolov, 2005 ) point out the importance of social indicators of sustainable tourism development. However, there is no holistic framework to select the social indicators to be used to assess the positive or negative impacts of the tourism sector on SVA. There is a considerable amount of literature that addresses the methodology and approaches in selecting social indicators for sustainable tourism development, but there is a gap in empirical studies which can be attributed to a lack of data, especially for a larger group of countries such as the EU 27. Depending on data availability and scope of research, authors use different social indicators, which makes comparison across empirical studies difficult. For example, Gkoumas ( 2019 ) uses the number of operators certified by an environmental or sustainability program, the number of accommodations that comply with local architecture, and the percentage of staff trained in environmental issues, while Burghelea et al. ( 2016 ) uses the participation of tourism in local value added and the percentage of tourist arrivals without tour operator services. These types of indicators could not be used in our analysis due to the lack of data for the EU 27 member countries.

In order to test whether there are significant differences in achieving SVA when it comes to countries with a higher share of renewables in total energy sources, and also between efficient and inefficient countries, we add two dummy variables: one for country efficiency and another for the share of renewables in total energy sources (Model 6). Both dummy variables are significant when considering them separately and together with the efficiency score (DEA_score). According to the efficiency score obtained from the DEA analysis, there are no significant differences between technically efficient and inefficient countries in generating SVA. However, when a country’s efficiency is examined in a way that efficient countries have a value of 1, while inefficient countries were assigned a value of 0, results show significant differences in generating SVA among two groups of countries (Model 6 and Model 7). Two groups of countries differ in their efficiency in using production inputs such as investment, energy consumption, and social security costs per employee in obtaining SVA. Technically efficient countries are more effective in using production inputs to generate SVA in the tourism sector. The investment will increase the efficiency of the tourism sector, which is contrary to the findings of Barisic and Cvetkovska ( 2017 ). Higher levels of social security and costs will also lead to higher sector SVA, according to OECD ( 2017a , 2017b ). Moreover, efficient countries consume less energy than the EU average when generating the same level of SVA. Efficient countries are more effective in using environmental inputs (Batur et al., 2015 ; Kosmaczewska, 2014 ; Toma, 2014 ; Lozowicka, 2020 ), especially RES, as they have a strong positive impact on SVA when above the EU average. Contrary to the results of Jebli et al. ( 2020 ), we found that countries with higher RES in total energy sources have higher SVA while they found the opposite effect of RES on value added in more developed countries (i.e., higher income countries). Usually more developed countries use more RES and the most significant and well-known barrier to renewable energy adoption is the cost of producing it. Our results show that countries with a higher share of renewables in total energy sources have higher value added. These findings confirm that efficient countries are more successful in their energy transition when they adopt market-based policies that focus on efficiency and RES, which is in line with Hermoso-Orzaes et al. ( 2020 ) and contributes to decarbonisation of the tourism sector. Moreover, according to the EPI ( 2022 ), efficient countries are efficient in their environmental performance, which is further confirmed by the fact that all technically efficient member countries in this study are among the top twenty countries in the world in terms of environmental performance (EPI, 2022 ).

5 Discussion and conclusions

The research results represent valuable information for policymakers in the further realization of strategic goals in the tourism industry, in which the role of RES is becoming increasingly important. Particular attention should be given to promoting solutions that lead to low-carbon development of countries but at the same time sustain or increase the economic benefits. Our results show that efficient countries as well as countries with a higher share of RES have a positive impact on SVA. Accordingly, harmonized energy policies and implementation strategies can promote greater use of RES in the tourism sector and increase energy efficiency in terms of lower energy consumption and higher SVA. The relationship we find between sustainable development and the use of RES is consistent with the principle of sustainable development.

The economic, environmental, and social components of sustainability in tourism represent the cornerstones of the sustainability concept. Policymakers should address all components to achieve the main sustainable goals they set out. Policymakers can pursue investments benefiting the sustainable development of tourism by motivating private and public investments and developing destinations that follow the transition to low-carbon development and add value to local communities.

Specifically, with regard to the economic component fixed capital and revenue have a significantly positive impact on SVA. Economic indicators show strong stability since they remain significant when controlling for environmental and social determinants as well as for DEA_score and dummy variables. We find that higher revenue correlates with higher productivity of workers in the tourism sector, which consequently leads to higher SVA. It also indicates that countries with higher revenues use their resources wisely, i.e., investing in employees leads to an increase in their productivity. The tourism industry's higher fixed capital means that countries with more fixed assets have investors that employ those assets more effectively to produce income, which results in higher SVA. Supporting technical advancements in the tourism industry improves productivity, which encourages specialization. Additionally, it generates new employment prospects with higher revenues for both industry workers and owners as well as stakeholders in general. The findings of the analysis of the relationship between revenue and SVA reveal that increased revenue is a sign of higher worker productivity in the tourism industry, which results in higher SVA. Additionally, it shows that wealthy countries make good use of their resources by investing in their workforce, which raises their output.

Somewhat contrary to the omnipresent narrative in media for absolute green and sustainable transformation we find that increased GHG emissions will lead to an initial increase in SVA as the tourism sector needs time and effort to transition from a resource-oriented to an environmental-oriented production process. Economic growth implies increased pollution due to increased SVA, as it requires more inputs and thus consumes more natural resources. Hence, it is of utmost importance to pay more attention to the quality of economic development in order to mitigate negative environmental externalities in the tourism sector.

We find that none of the variables from the social pillar we tested have a significant impact on SVA in the tourism sector. Furthermore, since there is no holistic framework for selecting the social indicators there is a gap in empirical studies which can be attributed to a lack of data, especially for a larger group of countries such as the EU 27 which we used.

Our results show that there are significant differences between technically efficient and inefficient countries in generating SVA. Two groups of countries differ in their efficiency in using production inputs such as investment, energy consumption, and social security costs per employee in obtaining SVA. Technically efficient countries (such as Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Spain) are more effective in using production inputs to generate SVA in the tourism sector. Investment will increase the efficiency of the tourism sector and higher levels of social security and costs will also lead to higher sector SVA. Moreover, efficient countries consume less energy than the EU average when generating the same level of SVA. Efficient countries are more effective in using environmental inputs especially RES, as they have a strong positive impact on SVA when above the EU average. By concentrating on renewable energy sources (RES), countries may be able to reduce their impact on the environment, particularly pollution caused by greenhouse gas emissions. Few to no greenhouse gases or air pollutants are released into the atmosphere by RES in the exploitation phase. This has a positive effect on the overall environment and results in a lower carbon footprint. The use of renewable energy sources triggers a positive impact on the sustainable value added, as they are viewed as environmentally beneficial since they emit little to no emissions in the exploitation phase. The use of RES provides an opportunity that social, environmental, and economic issues connected to the degradation of the environment to be avoided. Since renewable resources can be utilized repeatedly to provide energy, they will play a significant role in the generation of electricity in the near future for the tourism sector. This will further boost the sustainable value added during the transition phase.