"There are some who say that Communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin." --President John F. Kennedy, Berlin, Germany, June 26, 1963

You can hear a selection from John F. Kennedy's speech: AU Format (297K) WAV Format, Windows (297K) AIFF Format, MacIntosh (297K)

The speech was peppered with German and one sentence in Latin, written phonetically on one of the speech cards here. National Archives, John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts

The JFK Library Archives: An Inside Look

Digitized photographs from president john f. kennedy’s trip to germany.

( A version of this post was published on our previous blog on 12/17/2016 .)

By Laura Kintz, Archivist for Photographic and Textual Digitization

For those interested in President Kennedy’s trip to Germany in June of 1963, we are pleased to say that all White House Photographs documenting that visit are available online .

These photographs, covering June 23 to June 26, 1963, document President Kennedy’s only official trip to what was then a divided Germany. He spent four days in West Germany, also known as the Federal Republic of Germany, inaugurating a 10-day trip to Europe that also included visits to Ireland, England, and Italy. During those four days, the President visited several cities and towns, including Bonn, Cologne, Hanau, Frankfurt, and West Berlin. He delivered remarks, met with government officials, signed cities’ “Golden Books” for distinguished guests, visited with U.S. Embassy employees and members of the U.S. military, and greeted German well-wishers. Occurring during a contentious time in Germany’s history, President Kennedy’s visit represented the United States’ commitment to supporting West Germany and its leaders, including Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and President Heinrich Lübke.

Among President Kennedy’s numerous speeches in Germany was one given at the signing of the charter for the German Development Service, an organization equivalent to the Peace Corps. The President’s sister Eunice Kennedy Shriver and Secretary-General of the International Peace Corps, Richard Goodwin, were also present at the ceremony.

President Kennedy also took the time to visit American troops stationed at Fliegerhorst Kaserne, a military base in the town of Hanau. He viewed military displays and had lunch in the mess hall, where military cooks presented him with a cake in the shape of PT-109, the boat that the President commanded during World War II.

Of significance during President Kennedy’s trip to Germany were his remarks delivered at Rudolph Wilde Platz outside West Berlin’s city hall, Rathaus Schöneberg, on June 26. In this speech, the President famously declared, “Ich bin ein Berliner,” or “I am a Berliner.” One photograph from this event was previously cataloged, but newly-available photos provide different vantage points of the large crowds who gathered for the occasion.

West Berlin was not the only site where crowds converged to see President Kennedy. The entire trip was characterized by throngs of people who took to the streets and plazas of West Germany to see the President, either as his motorcade passed by or as he delivered remarks. These photographs provide evidence of the sheer volume of people who gathered for the President’s visit.

One notable result of cataloging these photographs was that metadata catalogers were able to identify numerous people who had previously been unidentified in the White House Photographs collection. Using both textual and audiovisual resources within the Kennedy Library’s collections, as well as contemporary newspaper accounts, Ancestry.com, and other resources, we were able to add 19 names to the Kennedy Library’s database of personal name browsing terms. Among them are: Director of Radio in the American Sector (RIAS) in Berlin, Robert Lochner, who served as President Kennedy’s translator for much of the trip; several members of the United States Armed Forces who were stationed in Germany, including Commander in Chief of the U.S. Army in Europe, General Paul L. Freeman, Jr., Commander in Chief of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, General Truman H. Landon and U.S. Army in Europe Project Officer, Colonel Frank Meszar; and Rector of Free University in Berlin, Ernst Heinitz, who conferred an honorary citizenship award upon the President on his last day in Germany.

President Kennedy’s trip to Germany represented a significant diplomatic venture of his presidency. The photographs from the trip, long available for viewing onsite at the Kennedy Library, may now be found by online users all over the world. In addition to the inclusion of browsing terms for individual people, other terms have been added to the photographs to aid in searching for specific subjects, places, and organizations. The images offer insight into President Kennedy’s travels to a much broader audience as a result.

Browse all photos from President Kennedy’s trip to Germany:

Germany, Bonn: Arrival, Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of West Germany pictured

Germany, Cologne: Kölner Rathaus (City Hall)

Germany, Cologne: Motorcade, Cathedral

Germany, Bonn: City Hall, ceremonies and remarks

Germany, Bonn: Address at the American Community Theater before the American Embassy staff

Germany, Bonn: Villa Hammerschmidt, Peace Corps Ceremony

Germany, Bonn: President Kennedy gives a press conference

Germany, Bonn: President Kennedy with Heinrich Lübke

Germany, Bad Godesburg, U.S. Ambassador’s Residence: President Kennedy signs Golden Book

Germany, Hanau: Arrival at Fliegerhorst Kaserne, address, and inspection of troops and equipment

Germany, Hanau: President Kennedy has lunch with U.S. enlisted troops and their officers at Fliegerhorst Kaserne

Germany, Hanau: Departure from Fliegerhorst Kaserne

Germany, Frankfurt: Frankfurt Rathaus

Germany, Frankfurt: President Kennedy gives address in Roemerberg Square

Germany, Frankfurt: President Kennedy at Paulskirche

Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy arrives at Tegel Airport

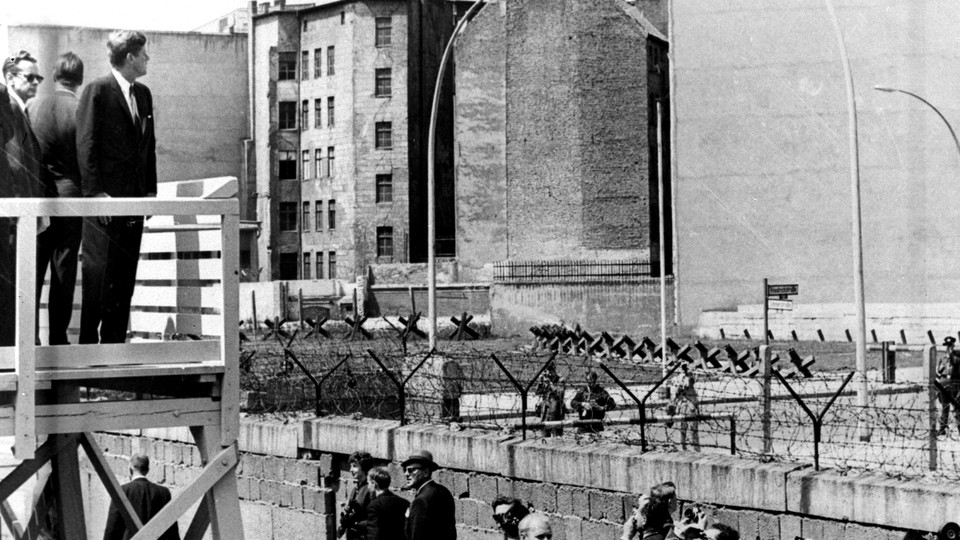

Germany, West Berlin, President Kennedy views the Berlin Wall at the Brandenburg Gate

Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy at Checkpoint Charlie

Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy addresses crowd at Rathaus Schöneberg

Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy in motorcade with Willy Brandt, Mayor of West Berlin and Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of West Germany

Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy addresses Free University

1963, John F. Kennedy – fliegerhorst kaserne germany Kenenth Miler 1911a1 45

I remember shaking his hand as a young Cub Scout in 1963 during his visit. This older woman next to me said” I’ll never wash my hand again”!

My father was in the Army stationed in Germany during President Kennedy’s visit. I have a photo of the President reviewing a Nike Hercules missile on June 25, 1963. My dad is the unit commander saluting the motorcade at the end of the row of soldiers. I will happily share this photo with you. I will attempt to attach it here, if that does not work, I will email it to you if you send me an email so I have an address.

I was a dependent of an Air Force Colonel stationed at Lindsey Air Station Headquarters U S Air Forces Europe (Wiesbaden). We went to the landing of JFK at the General Von Steuben Hotel and were crushed by the crowd of thousands. The streets were packed as far as the eye could see. Although you could see the helicopter land and President Kennedy get out, it was impossible to get very close. A few days later when JFK was departing Wiesbaden AFB, military personnel and dependents were allowed on the base to greet and send of President Kennedy. I was fortunate enough to be one of them. Although it was crowded, JFK spent some time walking along the fence line greeting the crowd. I had the great experience of being able to shake JFK’s hand as he moved long the fence. It was so meaningful and beyond belief. It was a great day and one which I will never forget.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

When JFK Told West Berliners That He Was One of Them

By: Jesse Greenspan

Updated: April 26, 2023 | Original: June 26, 2013

In June 1963, as the Cold War raged, President John F. Kennedy traveled to Germany to denounce communism and express U.S. support for the people there, whose country had been divvied up after World War II . His address in West Berlin, where he declared "Ich bin ein Berliner," struck a chord with the massive crowd, making it one of his most-remembered speeches.

After World War II , the victorious Allied powers divided Germany into four zones. Three of those—controlled by the United States, the United Kingdom and France, respectively—became democratic West Germany, whereas the one controlled by the Soviet Union became communist East Germany.

Berlin, the former capital, was similarly split despite being located squarely within East Germany’s borders, a situation that rankled the Soviet Union. In June 1948, the USSR cut off all land and water routes between West Berlin and the rest of West Germany in an attempt to gain control over the city. But the United States and its allies were able to overcome this 11-month blockade by airlifting in over 2.3 million tons of food and supplies.

Berlin remained a point of contention between the United States and the Soviet Union when Kennedy took office in January 1961. At a summit that June in Austria, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev threatened the sovereignty of West Berlin and ratcheted up the rhetoric, warning that it was “…up to the U.S. to decide whether there will be war or peace” between the two nations and insisting that as the Cold War heated up, “Force will be met by force.”

“Worst thing in my life,” Kennedy told a New York Times reporter afterwards. “He savaged me.”

Khrushchev then approved the construction of the Berlin Wall in order to prevent any more East Germans from fleeing to the West (an estimated 3.5 million had already done so). Barbed wire went up on August 13, 1961; concrete blocks later replaced it. More turmoil came in October, when Soviet and U.S. tanks rolled to within a few hundred feet of each other at Checkpoint Charlie , the crossing point for diplomats and other non-Germans. The 16-hour standoff, which precipitated worries about a World War III, ended without any shots being fired.

On June 23, 1963, Kennedy returned to Europe for the first time since sparring with Khrushchev in Austria. He visited Bonn, Cologne and Frankfurt in West Germany, where big crowds chanted his name and waved U.S. flags, before flying into West Berlin on the morning of June 26. On the way over he showed General James H. Polk, the U.S. commandant in Berlin, a draft of the speech he planned to give later that day. “This is terrible, Mr. President,” Polk reportedly said.

Kennedy agreed and began working out a more forceful version in his head as he toured Checkpoint Charlie and other locations around the city. He also inserted a little German, which he wrote phonetically on note cards. Meanwhile, at least 120,000 West Berliners—some estimates place the total as high as 450,000—had gathered in the plaza outside city hall to hear Kennedy speak.

Early in his address, the foreign language-challenged president broke out four German words he had supposedly been practicing for days. “Two thousand years ago the proudest boast was ‘civis Romanus sum,’” Kennedy said. “Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner.’” Legend holds that by including the article “ein,” Kennedy had called himself a jelly doughnut. But although speechwriter Ted Sorensen blamed himself for the alleged mistake in a memoir, German linguists maintain that the president used acceptable grammar.

Kennedy went on to lambaste the failures of communism , saying anyone who thought it was the wave of the future should come to Berlin. “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in,” JFK stated. After praising the people of West Berlin for being at the front lines of the Cold War , he finished up by repeating his soon-to-be famous phrase. “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner!’” he exclaimed.

The whole speech lasted only nine minutes. Kennedy then gave another address at the Free University of Berlin before flying to Ireland that evening. “We’ll never have another day like this one, as long as we live,” he reportedly said in reference to the enthusiastic crowds.

Although Kennedy was assassinated that November, his wish for the city to “be joined as one” came true when the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989. To this day he remains an admired figure in Berlin, which is hosting a series of lectures, films and exhibitions coinciding with the 50th anniversary of his visit.

HISTORY Vault: U.S. Presidents

Stream U.S. Presidents documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- BerlinGlobal

- Internships

- Amerika Haus

- Historical Background

- The Marshall Plan

- The Berlin Airlift

- John F. Kennedy Visit to Berlin

- Ronald Reagan Visit to Berlin

- Bill Clinton Visit to Berlin

- Barack Obama Visit to Berlin

- Famous German-Americans

- The Next Generation

- Community Message

- Letters of Support

John F. Kennedy Visit to Berlin, June, 26th, 1963

The US President, John F Kennedy, made a ground-breaking speech in Berlin offering American solidarity to the citizens of West Germany. A crowd of 120,000 Berliners gathered in front of the Schöneberg Rathaus (City Hall) to hear President Kennedy speak. They began gathering in the square long before he was due to arrive, and when he finally appeared on the podium they gave him an ovation of several minutes. In an impassioned speech, the president told them West Berlin was a symbol of freedom in a world threatened by the Cold War. His speech was punctuated throughout by rapturous cheers of approval. He ended on the theme he had begun with: "All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words, 'Ich bin ein Berliner.'" Kennedy's "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech was seen as a turning point in the Cold War. It was a major morale booster for West Germans, alarmed by the recently-built Berlin Wall. It also gave a strongly defiant message to the Soviet Union and effectively put down Moscow's hopes of driving the Allies out of West Berlin. Two months later, President Kennedy negotiated the first nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, in what was seen as a first step towards ending the Cold War.

delivered 26 June 1963, West Berlin The full text of Kennedy's "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech I am proud to come to this city as the guest of your distinguished Mayor, who has symbolized throughout the world the fighting spirit of West Berlin. And I am proud -- And I am proud to visit the Federal Republic with your distinguished Chancellor who for so many years has committed Germany to democracy and freedom and progress, and to come here in the company of my fellow American, General Clay, who who has been in this city during its great moments of crisis and will come again if ever needed. Two thousand years ago -- Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was "civis Romanus sum." Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is "Ich bin ein Berliner." (I appreciate my interpreter translating my German.) There are many people in the world who really don't understand, or say they don't, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin. There are some who say -- There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin. And there are some who say, in Europe and elsewhere, we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin. And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lass' sie nach Berlin kommen. Let them come to Berlin. Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect. But we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in -- to prevent them from leaving us. I want to say on behalf of my countrymen who live many miles away on the other side of the Atlantic, who are far distant from you, that they take the greatest pride, that they have been able to share with you, even from a distance, the story of the last 18 years. I know of no town, no city, that has been besieged for 18 years that still lives with the vitality and the force, and the hope, and the determination of the city of West Berlin. While the wall is the most obvious and vivid demonstration of the failures of the Communist system -- for all the world to see -- we take no satisfaction in it; for it is, as your Mayor has said, an offense not only against history but an offense against humanity, separating families, dividing husbands and wives and brothers and sisters, and dividing a people who wish to be joined together. What is -- What is true of this city is true of Germany: Real, lasting peace in Europe can never be assured as long as one German out of four is denied the elementary right of free men, and that is to make a free choice. In 18 years of peace and good faith, this generation of Germans has earned the right to be free, including the right to unite their families and their nation in lasting peace, with good will to all people. You live in a defended island of freedom, but your life is part of the main. So let me ask you, as I close, to lift your eyes beyond the dangers of today, to the hopes of tomorrow, beyond the freedom merely of this city of Berlin, or your country of Germany, to the advance of freedom everywhere, beyond the wall to the day of peace with justice, beyond yourselves and ourselves to all mankind. Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we look -- can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great Continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe. When that day finally comes, as it will, the people of West Berlin can take sober satisfaction in the fact that they were in the front lines for almost two decades. All -- All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin. And, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words "Ich bin ein Berliner."

Our Institutions:

- Academy for Cultural Diplomacy

- Inter Parliamentary Alliance for Human Rights

- ICD House of Arts & Culture

- Youth Education & Development

- Berlin Global

Our Programs:

- Center for Cultural Diplomacy Studies

- Human Rights & Peace Building

- Cultural Diplomacy Thematic Programs

- Experience Africa

© ICD - Institute for Cultural Diplomacy. All rights reserved | Contact | Imprint | Privacy Policy

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Why Mr Kennedy is in Europe - archive, June 1963

In the summer of 1963, President John F Kennedy visited Europe, including West Berlin, where he made his anti-communist ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech. As the Guardian’s Hella Pick explained at the time, the trip was a personal rescue attempt of the Atlantic alliance

P resident Kennedy could scarcely have chosen a worse moment for his European trip. The White House makes few bones about that. Nevertheless Mr Kennedy has never wavered from his decision to go. To cancel it at the last moment would only have created further embarrassment abroad. He has not been deterred by the civil rights crisis at home, Britain’s political troubles, the untimely elections in the Vatican. or the long drawn-out efforts to find a new Italian Government. There has been strong advice against the trip. Civil rights advocates consider the President must give all to the battle, including his continuous presence. Some of his own officials believe that the President may unwittingly only add to political confusion in Britain and Italy, and have argued that the trip at best will yield nothing positive and at worst will draw attention to the bankruptcy of America’s European policy, which is still reeling from the impact of General de Gaulle.

But the President evidently felt that a personal rescue attempt of the Atlantic alliance was essential. By going to Europe, and especially to its heart in Berlin, the President is trying to convince European leaders that General de Gaulle is wrong and that the United States commitment in Europe is constant and even increasing. He wants to impress on Britain, and more especially on Western Germany and Italy, the necessity for cementing the Atlantic alliance, and to convince them that the US has no intention of doing a deal with the Soviet Union at the expense of its allies – that, indeed, he would consider such a move against America’s insect interests. At the same time the President will certainly pursue the major theme he opened in his recent foreign policy speech at the American University in Washington, where he urged the need for peaceful coexistence with the Soviet Union and for a fresh look at East-West problems.

The US argument will be that the Soviet Union is on the defensive and that the Atlantic alliance has a hopeful opportunity for negotiation. But he may also carry a warning that the US cannot wait indefinitely while Europe makes up i:s mind whether to listen to him or to General de Gaulle. US officials still insist that the US has no quarrel with France. but it the President has evidently become convinced that General de Gaulle will stop at virtually nothing to divide Western Europe from Britain and the US. His actions are considered to have gone beyond mere nuisance value. The US resents the tact that the French decision against paying for United Nations peace-keeping operations was recently delivered in virtually identical terms with those of the Soviet announcement; it considers that French efforts are directed towards undermining the vital trade negotiations of the Kennedy round. French withdrawal of its naval forces from NATO is hardly helpful, and the French insistence that the US would not help to defend Europe against nuclear attack falls on receptive ears in Moscow and elsewhere in Europe.

The US has failed to out-manoeuvre France so far. President Kennedy is making an outstanding effort now. General de Gaulle will again be visiting Germany in July. The President, by engaging in a virtual popularity contest. is trying to insure against a further German effort to strengthen Franco-German relations at the expense of the Atlantic alliance.

By deciding to accept Mr Macmillan’s pressing invitation, President Kennedy certainly had more in mind than the need to confirm America’s stake in Europe. Britain’s leaders need little reassurance on that score. and President Kennedy would not have decided to rub more salt into French wounds if there had not been other objectives.

There have been many suggestions that the Admininstration continues to distrust Mr Harold Wilson, and that the President has no great objection to adding his small mite towards trying to keep the Conservative Party in office. However, most certainly the White House would deny any such motive. Anglo-American aid to India will be examined during the British visit, but the obvious major reason for going to London is to discuss the Anglo-American brief at the forthcoming test ban talks. The Moscow talks will be difficult and complex. Mr Kennedy wants to settle on a strategy that would not close the door to further negotiations even if there is failure in Moscow. He also wants agreement with Britain on the extent to which the West might offer further concessions in an effort to obtain a treaty.

The Administration does not consider that Mr Khrushchev’s recent remarks on the test ban treaty close the door to on-site inspection in the Soviet Union. But it believes that one more attempt is possible to convince the Soviet Union that on-site inspection would not in fact facilitate Western espionage.

The President takes with him to Europe two projects designed to confirm US determination for linking its fate to Europe. Alas, neither is an ace. The first Is the project for a multilateral NATO nuclear deterrent. The second is the Trade Expansion Act – the Kennedy round. Both are liable to cause as much dissension as they could help to cement unity. The proposals to establish a fleet of surface ships armed with Polaris missiles. jointly owned by NATO countries and manned with mixed crews, is if anything even less popular now than when it was first launched. It is widely regarded as a gimmick, even by many members of the Administration, and the Pentagon considers its military value as more than doubtful. Even its most ardent advocates agree that its main justification is political. They argue that a Polaris fleet would satisfy Germany’s nuclear aspirations without giving Germany a decisive hand on the trigger; and that it would at the same time strengthen Europe’s sense of participation in Western defence. The critics argue back that Germany had few nuclear aspirations until the US began to talk of a multilateral deterrent, and that Europe’s sense of participation in Atlantic defence would hardly be strengthened by a project which the military consider of doubtful value.

The President does not accept this argument. Nor could he really afford to: the Administration has thought up no alternative ideas to put in its place. His concern now Is to prevent the MLS – as it is now popularly known to insiders – from becoming a purely US-German enterprise. Indeed, the US would probably rather abandon it altogether if it cannot attract at least one other partner in addition to Germany. Ideally the President had hoped to set off on this trip with the assurance that Britain at least would definitely join, and that this would act as an additional spur on Italy. In fact. British doubts, linked to Mr Macmillan’s preoccupation with the Profumo affair, have put off the British decision, and the President has given up all hope of obtaining a decisive commitment during his present trip. Nor can he obtain one in Italy. This will obviously diminish the practical work of his talks with the Germans, since he will neither be able to confirm the creation of the MLS nor discuss Germany’s share of the cost. The Germans are reported to be more than dubious over the suggestion that they should share at least a third and possibly more of the cost.

The President’s other big project is now seen of equally dubious worth as a cement for the Atlantic alliance. The negotiations surrounding the application of the Trade Expansion Act threaten to divide rather than unite. The President will work hard to win Germany’s co-operation. But the Administration knows that powerful economic forces are pulling towards General de Gaulle’s inward-looking concept of the EEC.

Certainly on the eve of the presidential trip the storm signals are out in Washington. The President must always have one eye on Congress. Embattled in civil rights legislation. the liberal elements of Congress will be virtually powerless to stem the tide of Congressional opinion against the Europe that does not want to see a good thing when it is offered. Indeed, there are ominous signs of a Congressional demand to withdraw US military assistance to unco-operative NATO countries. If Europe does not accept the assurance for close co-operation which the President is now bringing, he may no longer be in a position later to offer any at ail. The President obviously hopes that this message will be heeded.

The Guardian view: President Kennedy in Europe

- From the Guardian archive

- John F Kennedy

- Berlin Wall

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

The Real Meaning of Ich Bin ein Berliner

In West Berlin in 1963, President Kennedy delivered his most eloquent speech on the world stage. The director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum tells the evocative story behind JFK’s words.

Other than ask not , they were the most-famous words he ever spoke. They drew the world’s attention to what he considered the hottest spot in the Cold War. Added at the last moment and scribbled in his own hand, they were not, like the oratory in most of his other addresses, chosen by talented speechwriters. And for a man notoriously tongue-tied when it came to foreign languages, the four words weren't even in English.

Ich bin ein Berliner.

These words, delivered on June 26, 1963, against the geopolitical backdrop of the Berlin Wall, endure because of the pairing of the man and the moment. John F. Kennedy’s defiant defense of democracy and self-government stand out as a high point of his presidency.

To appreciate their impact, one must understand the history. After World WarII, the capital of Hitler’s Third Reich was divided, like Germany itself, between the communist East and the democratic West. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev described West Berlin, surrounded on all sides by East Germany, as “a bone in my throat” and vowed to “eradicate this splinter from the heart of Europe.” Kennedy feared that any future European conflict, with the potential for nuclear war, would be sparked by Berlin.

At their summit meeting in Vienna in the spring of 1961, Khrushchev warned Kennedy that he would sign a treaty with East Germany restricting Western access to West Berlin. In response, Kennedy announced a major military buildup. In a television address to the nation on July 25, 1961, he described the embattled city as “the great testing place of Western courage and will” and declared that any attack on West Berlin would be viewed as an attack on the United States.

The speech had its desired effect. Khrushchev backed down from signing the treaty, even as thousands of East Germans continued crossing into West Berlin in search of freedom. In the early morning of August 13, 1961, the East German government, with Soviet support, sought to put this problem to rest, by building a wall of barbed wire across the heart of Berlin.

Tensions had abated slightly by the time Kennedy arrived for a state visit almost two years later. But the wall, an aesthetic and moral monstrosity now made mainly of concrete, remained. Deeply moved by the crowds that had welcomed him in Bonn and Frankfurt, JFK was overwhelmed by the throngs of West Berliners, who put a human face on an issue he had previously seen only in strategic terms. When he viewed the wall itself, and the barrenness of East Berlin on the other side, his expression turned grim.

Kennedy’s speechwriters had worked hard preparing a text for his speech, to be delivered in front of city hall. They sought to express solidarity with West Berlin’s plight without offending the Soviets, but striking that balance proved impossible. JFK was disappointed in the draft he was given. The American commandant in Berlin called the text “terrible,” and the president agreed.

So he fashioned a new speech on his own. Previously, Kennedy had said that in Roman times, no claim was grander than “I am a citizen of Rome.” For his Berlin speech, he had considered using the German equivalent, “I am a Berliner.”

Moments before taking the stage, during a respite in West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt’s office, JFK jotted down a few words in Latin and—with a translator’s help—the German version, written phonetically: Ish bin ein Bearleener .

Afterward it would be suggested that Kennedy had got the translation wrong—that by using the article ein before the word Berliner , he had mistakenly called himself a jelly doughnut. In fact, Kennedy was correct. To state Ich bin Berliner would have suggested being born in Berlin, whereas adding the word ein implied being a Berliner in spirit. His audience understood that he meant to show his solidarity.

Emboldened by the moment and buoyed by the adoring crowd, he delivered one of the most inspiring speeches of his presidency. “Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was ‘Civis Romanus sum,’ ” he proclaimed. “Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘ Ich bin ein Berliner !’ ”

With a masterly cadence, he presented a series of devastating critiques of life under communism:

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the communist world. Let them come to Berlin … There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin … And there are even a few who say that it’s true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lasst sie nach Berlin kommen — let them come to Berlin!

Kennedy cast a spotlight on West Berlin as an outpost of freedom and on the Berlin Wall as the communist world’s mark of evil. “Freedom has many difficulties, and democracy is not perfect,” he stated, “but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in.” He confidently predicted that, in time, the wall would fall, Germany would reunite, and democracy would spread throughout Eastern Europe.

The words rang true not only for the hundreds of thousands of people who were there but also for the millions around the world who saw the speech captured on film. Viewing the video today, one still sees a young statesman—in the prime of his life and his presidency—expressing an essential truth that runs throughout human history: the desire for liberty and self-government.

At the climax of his speech, the American leader identified himself with the inhabitants of the besieged city:

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free. When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe.

His conclusion linked him eternally to his listeners and to their cause: “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words Ich bin ein Berliner .”

Subscribe (and get 5 free books)

The past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past

Ich bin ein Berliner: JFK’s Berlin Speech, 26th June 1963

Barney White-Spunner

58 years ago JFK gave one of his best speeches. Speaking to huge crowds in West Berlin, he called on the free world to stand by Berliners divided by the Berlin Wall and threatened by their Communist neighbours. “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin”, Kennedy declared, to rapturous applause, “and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘ Ich bin ein Berliner ”. His speech writers needed a kicking as what he had actually said was that he was a Berlin doughnut – German is an unforgiving language – but that did not detract from the enormous impact his words had nor from the morale lift they gave to the citizens of a western city trapped in the communist bloc. It was one of the great post war speeches. Reagan’s speech 24 years later in front of Berlin’s iconic Brandenburg Gate, when he said “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall’, was also well received but never had quite the same impact; anyway by 1987 it was clear that Gorbachev was probably going to do as he was asked.

Kennedy, Brandt and Adenauer driving through Berlin. Credit: Creative Commons.

Kennedy’s speech mattered so much because the Wall had only gone up two years before. The western allies – the USA, Britain and France who all maintained garrisons in West Berlin – did nothing. Actually there was nothing they could do short of starting World War Three but Berliners felt that they had been betrayed. Willy Brandt, then Berlin’s charismatic mayor, had ranted to Kennedy that the USA had abandoned them. Kennedy’s visit to the city showed both American commitment and made Berlin the front line in the Cold War. He also strengthened a close link between the USA and Berlin born of the Berlin Airlift. Between June 1948 and May 1949 US aircrew made over a quarter of a million flights to keep Berliners alive as Stalin tried to starve them into submission; 31 Americans lost their lives. Only three years earlier those same crews had been dropping a more lethal cargo.

The unsmiling Soviet President Khrushchev felt he had to retaliate to Kennedy and a week later visited his satellite capital in East Berlin. His speech, perhaps unsurprisingly, failed to have quite the same effect. Yet despite feeling better about themselves for Kennedy’s very strong statement of support, Berliners had to live with that monstrous barrier of concrete and barbed wire, set about with watchtowers, death strips, machine guns, attack dogs and officious border guards for 28 years.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of its erection, on 13th August 1961, an event that will not pass unnoticed in the city now reunited since 1989. Parts of the Wall have been preserved. In Friedrichshain a long section has become an outside art gallery, the famous East Side Gallery, while a more sombre memorial and museum in Bernauer Straßeremembers the loss and suffering caused. In front of the Brandenburg Gate, and alongside the restored Reichstag, a line of cobbles in the street marks the one-time front line of the Free World.

Throughout its often violent and traumatic story, Berlin has always remembered through its buildings. While some European cities have practised a sort of heroic denial about their past, rebuilding themselves as they imagined they should have been, Berlin is comfortable in living alongside its history. How many other cities would put something as moving and important as the Holocaust Memorial in its very heart?

Credit: Creative Commons.

Perhaps the best example of this acceptance of Berlin’s past is the rebuilding of the Berliner Schloss. In 1415 the Hohenzollerns – kings of Prussia then emperors of Germany – took the twin fishing villages of Berlin and Cölln on the River Spree and made them their capital. In time they needed a suitable palace, as dynasties do, and successive kings built the huge Berliner Schloss on the island which divides the Spree and which came to form the city centre. Badly damaged in Hitler’s war, what remained was blown up in 1950 by the communist East German leader Walter Ulbricht. It was replaced by the Palast der Republik, which, in all its Soviet ugliness, was the asbestos ridden seat of East Germany’s nominal parliament. When Berlin was re-united in 1989 this was in its turn demolished, leaving an empty space at the very heart of one of the world’s great capital cities.

The debate as to how to fill that space was acrimonious and lasted 14 years. It was nuanced but essentially came down to being between those who thought the old Schloss should never have been demolished and should therefore be replaced and those who thought to do so would be to pander to a reactionary, authoritarian Berlin which was now an anachronism. What was needed, the modernists argued, was a futuristic building that portrayed opportunity and unity. Interestingly it was a debate that largely bypassed young Berliners who were more concerned about the city’s failure to deliver its new airport.

A panel of 17 international experts was invited to try to resolve the matter. Eventually they recommended that the old Schloss should be replaced but that the façade facing east, towards Alexanderplatz, would be modern. The Schloss, they argued, had always represented a synthesis of styles and the new façade would link the new buildings of East Berlin with the older Unter den Linden. Their recommendation was finally approved by the German parliament, the Bundestag, in 2002.

The completed building, now named the Humboldt Forum after two of Berlin’s most celebrated sons, should have opened last October. Frustrated by the pandemic it will, hopefully, be fully open later this year. Its purpose is, says Paul Spies, the art historian who heads Berlin’s museums, is to ‘show how the world is present in Berlin and Berlin is present in the world’. ‘It is not a museum’, says its new director Hartmut Dorgeloh, ‘it’s not a palace. It’s a forum, an accessible place where various parties congregate to engage with different ideas’.

There are those who remain unconvinced, one critic describing it as “Chernobyl – concrete on top of a problem’ but few can disagree that it draws together the previously divided city. Alongside Berlin’s cathedral and facing the facade of Schinkel’s Altes Museum across the Lustgarten, Berlin now has a centre on the island where the Hohenzollerns first built their fort six hundred years ago. The island is also home to Berlin’s incomparable series of museums, recently restored with equal success.

Sixty years after the Wall went up, JFK’s pledge has been amply redeemed. One of Europe’s great cities, its most exciting and innovative of cities, Berlin feels physically as well as politically united.

Barney White-Spunner is the author of B erlin: The Story of a City , a biography of the city from its founding in the Middle Ages to today.

You may like

Sign up to our Mailing List

Sign up to enter the draw for a book giveaway from a bestselling historian or fiction writer, and receive 3 free books

Germany: JFK visit, June 1963

About folder.

- Toasts of President and Adenauer, American Embassy Club, Bad Godesberg, 24 June 1963

- Toast of the President to Chancellor Adenauer, and Remarks at a Dinner at the American Embassy Club in Bad Godesberg, 24 June 1963

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: Arrival, Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of West Germany pictured

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Cologne: Kölner Rathaus (City Hall), 10:55AM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Cologne: Motorcade, Cathedral

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: City Hall, ceremonies and remarks, 1:25PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: Address at the American Community Theater before the American Embassy staff, 2:45PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: Villa Hammerschmidt, Peace Corps Ceremony, 11:40AM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: President Kennedy gives a press conference, 5:30PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bonn: President Kennedy with Heinrich Lübke

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Bad Godesberg, U.S. Ambassador's Residence: President Kennedy signs Golden Book, 6:20PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Hanau: Arrival at Fliegerhorst Kaserne, address, and inspection of troops and equipment, 10:45AM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Hanau: President Kennedy has lunch with U.S. enlisted troops and their officers at Fliegerhorst Kaserne, 12:15PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Hanau: Departure from Fliegerhorst Kaserne, 2:00PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Frankfurt: Frankfurt Rathaus, 3:15PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Frankfurt: President Kennedy gives address in Roemerberg Square, 4:00PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, Frankfurt: President Kennedy at Paulskirche, 4:35PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy arrives at Tegel Airport

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin, President Kennedy views the Brandenburg Gate at the Berlin Wall, 11:30AM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy at Checkpoint Charlie, 12:05PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin, President Kennedy addresses crowd at Rathaus Schöneberg, 12:50PM

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy in motorcade with Willie Brandt, Mayor of West Berlin and Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of West Germany

- Trip to Europe: Germany, West Berlin: President Kennedy addresses Free University, 3:30PM

- Events: 24 June 1963, Dinner (stag), Bonn, Germany

Schoolshistory.org.uk

History resources, stories and news. Author: Dan Moorhouse

Kennedy visit to Berlin

Kennedy’s visit to Berlin, 1963. The ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech

Source 1: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963

There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world – let them come to Berlin.

Source 2: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963

Two thousand years ago the proudest boast was “civis Romanus sum”. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is “Ich bin ein Berliner”.

Source 3: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963

I want to say, on behalf of my countrymen, who live many miles away on the other side of the Atlantic, who are far distant from you, that they take the greatest pride that they have been able to share with you, even from a distance, the story of the last 18 years.

I know of no town, no city, that has been besieged for 18 years that still lives with the vitality and the force, and the hope and the determination of the city of West Berlin.

Source 4: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963

Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, all are not free.

When all are free, then we can look forward to that day when this city will be joined as one and this country and this great continent of Europe in a peaceful and hopeful globe.

When that day finally comes, as it will, the people of West Berlin can take sober satisfaction in the fact that they were in the front lines for almost two decades.

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner”.

- 37420 Share on Facebook

- 2343 Share on Twitter

- 6736 Share on Pinterest

- 2917 Share on LinkedIn

- 5357 Share on Email

Subscribe to our Free Newsletter, Complete with Exclusive History Content

Thanks, I’m not interested

Accessibility links

- Skip to content

- Accessibility Help

JFK's visit to Berlin in 1963

President John F Kennedy's historic visit to Berlin in 1963 changed the city and its place in history. He said that all free men were citizens of Berlin and made his famous statement, "Ich bin ein Berliner." We are told how important this was in making Berlin not just a divided city, but a symbol, and a city for everyone.

Explain the importance of an American president visiting Berlin after the Berlin wall had been built to split the city. Discuss the impact that this had. Research could be done on life in the divided city. Introduce language by explaining how to form adjectives from place names. Give students a vocabulary exercise consisting of a list of some of these adjectives and a list in English of well-known items which they should match up, eg 'Kasseler', 'Berliner', 'Wiener'.

GCSE Subjects GCSE Subjects up down

- Art and Design

- Biology (Single Science)

- Chemistry (Single Science)

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Design and Technology

- Digital Technology (CCEA)

- English Language

- English Literature

- Home Economics: Food and Nutrition (CCEA)

- Hospitality (CCEA)

- Irish – Learners (CCEA)

- Journalism (CCEA)

- Learning for Life and Work (CCEA)

- Maths Numeracy (WJEC)

- Media Studies

- Modern Foreign Languages

- Moving Image Arts (CCEA)

- Physical Education

- Physics (Single Science)

- Religious Studies

- Welsh Second Language (WJEC)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Ich bin ein Berliner" (German pronunciation: [ɪç ˈbɪn ʔaɪn bɛʁˈliːnɐ]; "I am a Berliner") is a speech by United States President John F. Kennedy given on June 26, 1963, in West BerlinIt is one of the best-known speeches of the Cold War and among the most famous anti-communist speeches.. Twenty-two months earlier, East Germany had erected the Berlin Wall to prevent mass emigration to ...

Berlin was at the heart of the Cold War. In 1962, the Soviets and East Germans added a second barrier, about 100 yards behind the original wall, creating a tightly policed no man's land between the walls. After the wall went up, more than 260 people died attempting to flee to the West. Though Kennedy chose not to challenge directly the Soviet ...

It was another 26 years before the Berlin Wall finally fell. And a few months after his visit to West Berlin, on November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. The ...

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum is dedicated to the memory of our nation's thirty-fifth president and to all those who through the art of politics seek a new and better world. Columbia Point, Boston MA 02125 (617) 514-1600. Motion picture covering President John F. Kennedy's visit to Berlin, Germany.

National Archives, John F. Kennedy Library (NLK-29248) On June 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy delivered a speech that electrified an adoring crowd gathered in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. As he paid tribute to the spirit of Berliners and to their quest for freedom, the crowd roared with approval upon hearing the the President's dramatic ...

Listen to speech. View related documents.. President John F. Kennedy West Berlin June 26, 1963 [This version is published in the Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963.Both the text and the audio versions omit the words of the German translator.

SORENSEN: "When we departed he said 'Phew! We'll never have another day like this as long as we live.'". NARRATOR: Kennedy's message is a free West Berlin is inseparable from the freedom of the West. John F. Kennedy visiting West Berlin in June 1963 and delivering his "Ich bin ein Berliner" ("I Am a Berliner") speech.

Kennedy's visit to the divided city on 26 June 1963 was the highlight of his three-day visit to Germany. On that Wednesday, the American president landed at 9.45 a.m. at the military section of Tegel Airport. After the guard of honour had been removed, Kennedy was warmly welcomed by Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, Berlin's Governing Mayor ...

President John F. Kennedy, Remarks at the Rudolph Wilde Platz, June 26, 1963 West Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany I am proud to come to the city as the guest of your distinguished Mayor, who has symbolized throughout the world the fighting spirit of West Berlin. And I am proud to visit the Federal

(A version of this post was published on our previous blog on 12/17/2016.) By Laura Kintz, Archivist for Photographic and Textual Digitization. For those interested in President Kennedy's trip to Germany in June of 1963, we are pleased to say that all White House Photographs documenting that visit are available online.. These photographs, covering June 23 to June 26, 1963, document President ...

President John F. Kennedy expresses solidarity with democratic German citizens in a speech on June 26, 1963. In front of the Berlin Wall that separated the city into democratic and communist ...

Updated: April 26, 2023 | Original: June 26, 2013. In June 1963, as the Cold War raged, President John F. Kennedy traveled to Germany to denounce communism and express U.S. support for the people ...

The US President, John F Kennedy, made a ground-breaking speech in Berlin offering American solidarity to the citizens of West Germany. A crowd of 120,000 Berliners gathered in front of the Schöneberg Rathaus (City Hall) to hear President Kennedy speak. They began gathering in the square long before he was due to arrive, and when he finally ...

Why Mr Kennedy is in Europe - archive, June 1963. In the summer of 1963, President John F Kennedy visited Europe, including West Berlin, where he made his anti-communist 'Ich bin ein Berliner ...

In Berlin, an immense crowd of 120,000 Berliners gathered in the Rudolph Wilde Platz near the Berlin Wall to listen to hear President Kennedy speak. They began gathering in the square long before he was due to arrive, and when President Kennedy finally appeared on the podium after having made a visit to Checkpoint Charlie at the Berlin Wall ...

U.S. President John F. Kennedy visited Berlin on June 26, 1963. The highlight of his seven-and-a-half-hour stay was his speech in front of Schöneberg City Hall with the legendary final sentence "Ich bin ein Berliner". U.S. President John F. Kennedy on June 26, 1963, during his historic speech in front of Schöneberg City Hall.

Ich bin ein Berliner. These words, delivered on June 26, 1963, against the geopolitical backdrop of the Berlin Wall, endure because of the pairing of the man and the moment. John F. Kennedy's ...

On June 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy visited West Berlin, where he delivered his famous speech expressing solidarity with the city's residents, declar...

Kennedy's visit to the city showed both American commitment and made Berlin the front line in the Cold War. He also strengthened a close link between the USA and Berlin born of the Berlin Airlift. Between June 1948 and May 1949 US aircrew made over a quarter of a million flights to keep Berliners alive as Stalin tried to starve them into ...

This folder contains material collected by the office of President John F. Kennedy's secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, concerning Germany. Materials concern President Kennedy's visit to Germany (Federal Republic) on June 23-26, 1963. Also included in this folder is a transcript of Chancellor of Germany (Federal Republic) Konrad Adenauer's television address on the eve of the President's visit and a ...

Kennedy's visit to Berlin, 1963. The 'Ich bin ein Berliner' speech. Sources: Source 1: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963. There are many people in the world who really don't understand, or say they don't, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world - let them come to Berlin. Source 2: John F Kennedy, Berlin, 1963.

DescriptionClassroom Ideas. President John F Kennedy's historic visit to Berlin in 1963 changed the city and its place in history. He said that all free men were citizens of Berlin and made his ...