Cutting Edge | Bringing cultural tourism back in the game

The growth of cultural tourism

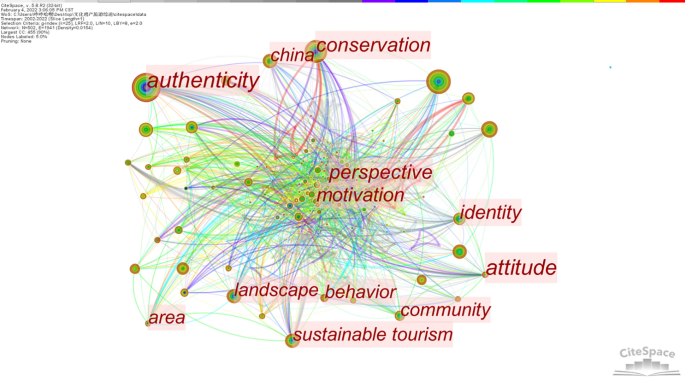

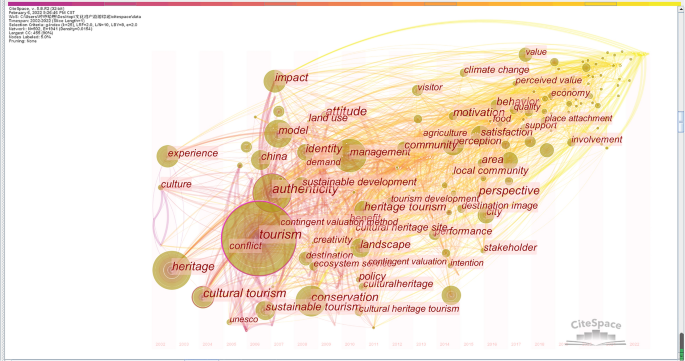

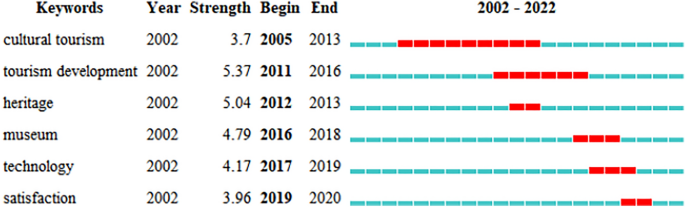

People have long traveled to discover and visit places of historical significance or spiritual meaning, to experience different cultures, as well as to learn about, exchange and consume a range of cultural goods and services. Cultural tourism as a concept gained traction during the 1990s when certain sub-sectors emerged, including heritage tourism, arts tourism, gastronomic tourism, film tourism and creative tourism. This took place amidst the rising tide of globalization and technological advances that spurred greater mobility through cheaper air travel, increased accessibility to diverse locations and cultural assets, media proliferation, and the rise of independent travel. Around this time, tourism policy was also undergoing a shift that was marked by several trends. These included a sharper focus on regional development, environmental issues, public-private partnerships, industry self-regulation and a reduction in direct government involvement in the supply of tourism infrastructure. As more cultural tourists have sought to explore the cultures of the destinations, greater emphasis has been placed on the importance of intercultural dialogue to promote understanding and tolerance. Likewise, in the face of globalization, countries have looked for ways to strengthen local identity, and cultural tourism has also been engaged as a strategy to achieve this purpose. Being essentially place-based, cultural tourism is driven by an interest to experience and engage with culture first-hand. It is backed by a desire to discover, learn about and enjoy the tangible and intangible cultural assets offered in a tourism destination, ranging from heritage, performing arts, handicrafts, rituals and gastronomy, among others.

Cultural tourism is a leading priority for the majority of countries around the world -featuring in the tourism policy of 90% of countries, based on a 2016 UNWTO global survey . Most countries include tangible and intangible heritage in their definition of cultural tourism, and over 80% include contemporary culture - film, performing arts, design, fashion and new media, among others. There is, however, greater need for stronger localisation in policies, which is rooted in promoting and enhancing local cultural assets, such as heritage, food, festivals and crafts. In France, for instance, the Loire Valley between Sully-sur-Loire and Chalonnes , a UNESCO World Heritage site, has established a multidisciplinary team that defends the cultural values of the site, and advises the authorities responsible for the territorial development of the 300 km of the Valley.

While cultural tourism features prominently in policies for economic growth, it has diverse benefits that cut across the development spectrum – economic, social and environmental. Cultural tourism expands businesses and job opportunities by drawing on cultural resources as a competitive advantage in tourism markets. Cultural tourism is increasingly engaged as a strategy for countries and regions to safeguard traditional cultures, attract talent, develop new cultural resources and products, create creative clusters, and boost the cultural and creative industries. Cultural tourism, particularly through museums, can support education about culture. Tourist interest can also help ensure the transmission of intangible cultural heritage practices to younger generations.

StockSnap, Pixabay

Cultural tourism can help encourage appreciation of and pride in local heritage, thus sparking greater interest and investment in its safeguarding. Tourism can also drive inclusive community development to foster resiliency, inclusivity, and empowerment. It promotes territorial cohesion and socioeconomic inclusion for the most vulnerable populations, for example, generating economic livelihoods for women in rural areas. A strengthened awareness of conservation methods and local and indigenous knowledge contributes to long-term environmental sustainability. Similarly, the funds generated by tourism can be instrumental to ensuring ongoing conservation activities for built and natural heritage.

The growth of cultural tourism has reshaped the global urban landscape over the past decades, strongly impacting spatial planning around the world. In many countries, cultural tourism has been leveraged to drive urban regeneration or city branding strategies, from large-sized metropolises in Asia or the Arab States building on cultural landmarks and contemporary architecture to drive tourism expansion, to small and middle-sized urban settlements enhancing their cultural assets to stimulate local development. At the national level, cultural tourism has also impacted planning decisions, encouraging coastal development in some areas, while reviving inland settlements in others. This global trend has massively driven urban infrastructure development through both public and private investments, impacting notably transportation, the restoration of historic buildings and areas, as well as the rehabilitation of public spaces. The expansion of cultural city networks, including the UNESCO World Heritage Cities programme and the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, also echoes this momentum. Likewise, the expansion of cultural routes, bringing together several cities or human settlements around cultural commonalities to stimulate tourism, has also generated new solidarities, while influencing economic and cultural exchanges between cities across countries and regions.

Despite tourism’s clear potential as a driver for positive change, challenges exist, including navigating the space between economic gain and cultural integrity. Tourism’s crucial role in enhancing inclusive community development can often remain at the margins of policy planning and implementation. Rapid and unplanned tourism growth can trigger a range of negative impacts, including pressure on local communities and infrastructure from overtourism during peak periods, gentrification of urban areas, waste problems and global greenhouse gas emissions. High visitor numbers to heritage sites can override their natural carrying capacity, thus undermining conservation efforts and affecting both the integrity and authenticity of heritage sites. Over-commercialization and folklorization of intangible heritage practices – including taking these practices out of context for tourism purposes - can risk inadvertently changing the practice over time. Large commercial interests can monopolize the benefits of tourism, preventing these benefits from reaching local communities. An excessive dependency on tourism can also create localized monoeconomies at the expense of diversification and alternative economic models. When mismanaged, tourism can, therefore, have negative effects on the quality of life and well-being of local residents, as well as the natural environment.

These fault lines became more apparent when the pandemic hit – revealing the extent of over-dependence on tourism and limited structures for crisis prevention and response. While the current situation facing tourism is unpredictable, making it difficult to plan, further crises are likely in the years to come. Therefore, the pandemic presents the opportunity to experiment with new models to shape more effective and sustainable alternatives for the future.

hxdyl, Getty Images Pro

Harnessing cultural tourism in policy frameworks

From a policy perspective, countries around the world have employed cultural tourism as a vehicle to achieve a range of strategic aims. In Panama, cultural tourism is a key component of the country’s recently adopted Master Plan for Sustainable Tourism 2020-2025 that seeks to position Panama as a worldwide benchmark for sustainable tourism through the development of unique heritage routes. Cultural tourism can be leveraged for cultural diplomacy as a form of ‘soft power’ to build dialogue between peoples and bolster foreign policy. For instance, enhancing regional cooperation between 16 countries has been at the heart of UNESCO’s transnational Silk Roads Programme, which reflects the importance of culture and heritage as part of foreign policy. UNESCO has also partnered with the EU and National Geographic to develop World Heritage Journeys, a unique travel platform that deepens the tourism experience through four selected cultural routes covering 34 World Heritage sites. Also in Europe, cultural tourism has been stimulated through the development of cultural routes linked to food and wine , as well as actions to protect local food products, such as through labels and certificates of origin. The Emilia-Romagna region in Italy, for example, produces more origin-protected food and drink than any other region in the country. One of the regions' cities Parma - a UNESCO Creative City (Gastronomy) and designated Italian Capital for Culture (2020-2021) - plans to resume its cultural activities to boost tourism once restrictions have eased. Meanwhile, Spain has recently taken steps to revive its tourism industry through its cities inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List . In this regard, the Group of the 15 Spanish World Heritage Cities met recently to discuss the country's Modernization and Competitiveness Plan for the tourism sector. Cultural tourism has progressively featured more prominently in the policies of Central Asian and Eastern European countries, which have sought to revive intangible heritage and boost the creative economy as part of strategies to strengthen national cultural identity and open up to the international community. In Africa, cultural tourism is a growing market that is driven by its cultural heritage, crafts, and national and regional cultural events. Major festivals such as Dak-Art in Senegal, Bamako Encounters Photography Biennial in Mali, Sauti za Busara in United Republic of Tanzania, Pan-African Festival of Cinema and Television of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, and Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Ghana are just a handful of vibrant and popular platforms in the continent that share cultural expressions, generate income for local economies and strengthen Pan-African identity.

Countries are increasingly seeking alliances with international bodies to advance tourism. National and local governments are working together with international entities, such as UNESCO, UNWTO and OECD in the area of sustainable tourism. In 2012, UNESCO’s Sustainable Tourism Programme was adopted, thereby breaking new ground to promote tourism a driver for the conservation of cultural and natural heritage and a vehicle for sustainable development. In 2020, UNESCO formed the Task Force on Culture and Resilient Tourism with the Advisory Bodies to the 1972 World Heritage Convention (ICOMOS, IUCN, ICCROM) as a global dialogue platform on key issues relating to tourism and heritage management during and beyond the crisis. UNESCO has also collaborated with the UNWTO on a set of recommendations for inclusive cultural tourism recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. In response to the crisis, the Namibian Government, UNESCO and UNDP are working together on a tourism impact study and development strategy to restore the tourism sector, especially cultural tourism.

UNESCO has scaled up work in cultural tourism in its work at field level, supporting its Member States and strengthening regional initiatives. In the Africa region, enhancing cultural tourism has been reported as a policy priority across the region. For example, UNESCO has supported the Government of Ghana in its initiative Beyond the Return, in particular in relation to its section on cultural tourism. In the Pacific, a Common Country Assessment (CCA) has been carried out for 14 SIDS countries, with joint interagency programmes to be created building on the results. Across the Arab States, trends in tourism after COVID, decent jobs and cultural and creative industries are emerging as entry points for different projects throughout the region. In Europe, UNESCO has continued its interdisciplinary work on visitor centres in UNESCO designated sites, building on a series of workshops to strengthen tourism sustainability, community engagement and education through heritage interpretation. In the Latin America and the Caribbean region, UNESCO is working closely with Member States, regional bodies and the UN system building on the momentum on the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development, including through Creative Cities, and the sustainable recovery of the orange economy, among others.

BS1920, Pixabay

In the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, tourism has the potential to contribute, directly or indirectly, to all of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Tourism is directly mentioned in SDGs 8, 12 and 14 on inclusive and sustainable economic growth, sustainable consumption and production (SCP) and the sustainable use of oceans and marine resources, respectively. This is mirrored in the VNRs put forward by countries, who report on cultural tourism notably through the revitalization of urban and rural areas through heritage regeneration, festivals and events, infrastructure development, and the promotion of local cultural products. The VNRs also demonstrate a trend towards underlining more sustainable approaches to tourism that factor in the environmental dimensions of tourism development.

Several countries have harnessed cultural tourism as a policy panacea for economic growth and diversification. As part of Qatar's National Vision 2030 strategy, for example, the country has embarked on a development plan that includes cultural tourism through strengthening its culture-based industries, including calligraphy, handicrafts and living heritage practices. In the city of Abu Dhabi in the UAE, cultural tourism is part of the city’s plan for economic diversification and to steer its domestic agenda away from a hydrocarbon-based economy. The Plan Abu Dhabi 2030 includes the creation of a US$27 billion cultural district on Saadiyat Island, comprising a cluster of world-renowned museums, and cultural and educational institutions designed by international star architects to attract tourism and talent to the city. Since 2016, Saudi Arabia has taken decisive action to invest in tourism, culture and entertainment to reduce the country’s oil dependency, while also positioning the country as a global cultural destination. Under the 2020 G20 Saudi Presidency, the UNWTO and the G20 Tourism Working Group launched the AlUla Framework for Inclusive Community Development through Tourism to better support inclusive community development and the SDGs. The crucial role of tourism as a means of sustainable socio-economic development was also underlined in the final communique of the G20 Tourism Ministers in October last.

Siem Reap, Cambodia by nbriam

On the other hand, cultural tourism can catalyse developments in cultural policy. This was the case in the annual Festival of Pacific Arts (FestPac) that triggered a series of positive policy developments following its 2012 edition that sought to strengthen social cohesion and community pride in the context of a prolonged period of social unrest. The following year, Solomon Islands adopted its first national culture policy with a focus on cultural industries and cultural tourism, which resulted in a significant increase in cultural events being organized throughout the country.

When the pandemic hit, the geographic context of some countries meant that many of them were able to rapidly close borders and prioritize domestic tourism. This has been the case for countries such as Australia and New Zealand. However, the restrictions have been coupled by significant economic cost for many Small Island Developing States (SIDS) whose economies rely on tourism and commodity exports. Asia Pacific SIDS, for example, are some of the world’s leading tourist destinations. As reported in the Tracker last June , in 2018, tourism earnings exceeded 50% of GDP in Cook Islands, Maldives and Palau and equaled approximately 30% of GDP in Samoa and Vanuatu. When the pandemic hit in 2020, the drop in British tourists to Spain’s Balearic Islands resulted in a 93% downturn in visitor numbers , forcing many local businesses to close. According to the World Economic Outlook released last October, the economies of tourism-dependent Caribbean nations are estimated to drop by 12%, while Pacific Island nations, such as Fiji, could see their GDP shrink by a staggering 21% in 2020.

Socially-responsible travel and ecotourism have become more of a priority for tourists and the places they visit. Tourists are increasingly aware of their carbon footprint, energy consumption and the use of renewable resources. This trend has been emphasized as a result of the pandemic. According to recent survey by Booking.com, travelers are becoming more conscientious of how and why they travel, with over two-thirds (69%) expecting the travel industry to offer more sustainable travel options . Following the closures of beaches in Thailand, for example, the country is identifying ways to put certain management policies in place that can strike a better balance with environmental sustainability. The UNESCO Sustainable Tourism Pledge launched in partnership with Expedia Group focuses on promoting sustainable tourism and heritage conservation. The pledge takes an industry-first approach to environmental and cultural protection, requiring businesses to introduce firm measures to eliminate single-use plastics and promote local culture. The initiative is expanding globally in 2021 as a new, more environmentally and socially conscious global travel market emerges from the COVID-19 context.

Senja, Norway by Jarmo Piironen

Climate change places a heavy toll on heritage sites, which exacerbates their vulnerability to other risks, including uncontrolled tourism. This was underlined in the publication “World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate” , published by UNESCO, UNEP and the Union of Concerned Scientists, which analyses the consequences of climate change on heritage, and its potential to permanently change or destroy a site’s integrity and authenticity. Extreme weather events, safety issues and water shortages, among others, can thwart access to sites and hurt the economic livelihoods of tourism service providers and local communities. Rising sea levels will increasingly impact coastal tourism, the largest component of the sector globally. In particular, coral reefs - contributing US$11.5 billion to the global tourism economy – are at major risk from climate change.

Marine sites are often tourist magnets where hundreds of thousands of annual visitors enjoy these sites on yachts and cruise ships. In the case of UNESCO World Heritage marine sites – which fall under the responsibility of governments - there is often a reliance on alternative financing mechanisms, such as grants and donations, and partnerships with non-governmental organizations and/or the private sector, among others. The West Norwegian Fjords – Geirangerfjord and Nærøyfjord in Norway derives a substantial portion of its management budget from sources other than government revenues. The site has benefited from a partnership with the private sector company Green Dream 2020, which only allows the “greenest” operators to access the site, and a percentage of the profits from tours is reinjected into the long-term conservation of the site. In iSimangaliso in South Africa, a national law that established the World Heritage site’s management system was accompanied by the obligation to combine the property’s conservation with sustainable economic development activities that created jobs for local people. iSimangaliso Wetland Park supports 12,000 jobs and hosts an environmental education programme with 150 schools. At the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, where 91% of all local jobs are linked to the Reef, the Coral Nurture Programme undertakes conservation through planting coral, and promotes local stewardship and adaptation involving the whole community and local tourist businesses.

Grafner, Getty Images

With borders continuing to be closed and changeable regulations, many countries have placed a focus on domestic tourism and markets to stimulate economic recovery. According to the UNWTO, domestic tourism is expected to pick up faster than international travel, making it a viable springboard for economic and social recovery from the pandemic. In doing so it will serve to better connect populations to their heritage and offer new avenues for cultural access and participation. In China, for example, the demand for domestic travel is already approaching pre-pandemic levels. In Russian Federation, the Government has backed a programme to promote domestic tourism and support small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as a cashback scheme for domestic trips, which entitles tourists to a 20% refund for their trip. While supporting domestic tourism activities, the Government of Palau is injecting funds into local businesses working in reforestation and fishing in the spirit of building new sustainable models. The measures put in place today will shape the tourism to come, therefore the pandemic presents an opportunity to build back a stronger, more agile and sustainable tourism sector.

Local solutions at the helm of cultural tourism

While state-led policy interventions in cultural tourism remain crucial, local authorities are increasingly vital stakeholders in the design and implementation of cultural tourism policies. Being close to the people, local actors are aware of the needs of local populations, and can respond quickly and provide innovative ideas and avenues for policy experimentation. As cultural tourism is strongly rooted to place, cooperating with local decision-makers and stakeholders can bring added value to advancing mutual objectives. Meanwhile, the current health crisis has severely shaken cities that are struggling due to diminished State support, and whose economic basis strongly relies on tourism. Local authorities have been compelled to innovate to support local economies and seek viable alternatives, thus reaffirming their instrumental role in cultural policy-making.

Venice, Oliver Dralam/Getty Images

Cultural tourism can be a powerful catalyst for urban regeneration and renaissance, although tourism pressure can also trigger complex processes of gentrification. Cultural heritage safeguarding enhances the social value of a place by boosting the well-being of individuals and communities, reducing social inequalities and nurturing social inclusion. Over the past decade, the Malaysian city of George Town – a World Heritage site – has implemented several innovative projects to foster tourism and attract the population back to the city centre by engaging the city’s cultural assets in urban revitalization strategies. Part of the income generated from tourism revenues contributes to conserving and revitalizing the built environment, as well as supporting housing for local populations, including lower-income communities. In the city of Bordeaux in France , the city has worked with the public-private company InCité to introduce a system of public subsidies and tax exemption to encourage the restoration of privately-owned historical buildings, which has generated other rehabilitation works in the historic centre. The city of Kyoto in Japan targets a long-term vision of sustainability by enabling local households to play an active role in safeguarding heritage by incrementally updating their own houses, thus making the city more resilient to gentrification. The city also actively supports the promotion of its intangible heritage, such as tea ceremonies, flower arrangement, seasonal festivals, Noh theatre and dance. This year marks the ten-year anniversary of the adoption of the UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). The results of a UNESCO survey carried out among Member States in 2019 on its implementation show that 89% of respondents have innovative services or tourism activities in place for historic areas, which demonstrates a precedence for countries to capitalize on urban cultural heritage for tourism purposes.

Cultural tourism has been harnessed to address rural-urban migration and to strengthen rural and peripheral sub-regions. The city of Suzhou – a World Heritage property and UNESCO Creative City (Crafts and Folk Art) - has leveraged its silk embroidery industry to strengthen the local rural economy through job creation in the villages of Wujiang, located in a district of Suzhou. Tourists can visit the ateliers and local museums to learn about the textile production. In northern Viet Nam, the cultural heritage of the Quan họ Bắc Ninh folk songs, part of the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, is firmly rooted in place and underlined in its safeguarding strategies in 49 ancient villages, which have further inspired the establishment of some hundreds of new Quan họ villages in the Bắc Ninh and Bắc Giang provinces.

Many top destination cities are known for their iconic cultural landmarks. Others create a cultural drawcard to attract visitors to the city. France, the world's number one tourist destination , attracts 89 million visitors every year who travel to experience its cultural assets, including its extensive cultural landmarks. In the context of industrial decline, several national and local governments have looked to diversify infrastructure by harnessing culture as a new economic engine. The Guggenheim museum in Bilbao in Spain is one such example, where economic diversification and unemployment was addressed through building a modern art museum as a magnet for tourism. The museum attracts an average of 900,000 visitors annually, which has strengthened the local economy of the city. A similar approach is the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), established in 2011 by a private entrepreneur in the city of Hobart in Australia, which has catalysed a massive increase of visitors to the city. With events such as MONA FOMA in summer and Dark MOFO in winter, the museum staggers visitor volumes to the small city to avoid placing considerable strain on the local environment and communities. Within the tourism sector, cultural tourism is also well-positioned to offer a tailored approach to tourism products, services and experiences. Such models have also supported the wider ecosystems around the iconic cultural landmarks, as part of “destination tourism” strategies.

Destination tourism encompasses festivals, live performance, film and festive celebrations as drawcards for international tourists and an economic driver of the local economy. Over the past three decades, the number of art biennials has proliferated. Today there are more than 300 biennials around the world , whose genesis can be based both on artistic ambitions and place-making strategies to revive specific destinations. As a result of COVID-19, many major biennials and arts festivals have been cancelled or postponed. Both the Venice Architecture and Art Biennales have been postponed to 2022 due to COVID-19. The Berlin International Film Festival will hold its 2021 edition online and in selected cinemas. Film-induced tourism - motivated by a combination of media expansion, entertainment industry growth and international travel - has also been used for strategic regional development, infrastructure development and job creation, as well to market destinations to tourists. China's highest-grossing film of 2012 “Lost in Thailand”, for example, resulted in a tourist boom to Chiang Mai in Thailand, with daily flights to 17 Chinese cities to accommodate the daily influx of thousands of tourists who came to visit the film’s location. Since March 2020, tourism-related industries in New York City in the United States have gone into freefall, with revenue from the performing arts alone plunging by almost 70%. As the city is reliant on its tourism sector, the collapse of tourism explains why New York’s economy has been harder hit than other major cities in the country. Meanwhile in South Africa, when the first ever digital iteration of the country’s annual National Arts Festival took place last June, it also meant an estimated US$25.7 million (R377 million) and US$6.4 million (R94 million) loss to the Eastern Cape province and city of Makhanda (based on 2018 figures), in addition to the US$1.4 million (R20 million) that reaches the pockets of the artists and supporting industries. The United Kingdom's largest music festival, Glastonbury, held annually in Somerset, recently cancelled for the second year running due to the pandemic, which will have ripple effects on local businesses and the charities that receive funding from ticket sales.

Similarly, cancellations of carnivals from Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands to Binche in Belgium has spurred massive losses for local tourism providers, hotels, restaurants, costume-makers and dance schools. In the case of the Rio de Janeiro Carnival in Brazil, for instance, the city has amassed significant losses for the unstaged event, which in 2019 attracted 1.5 million tourists from Brazil and abroad and generated revenues in the range of US$700 million (BRL 3.78 billion). The knock-on effect on the wider economy due to supply chains often points to an estimated total loss that is far greater than those experienced solely by the cultural tourism sector.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain by erlucho

Every year, roughly 600 million national and international religious and spiritual trips take place , generating US$18 billion in tourism revenue. Pilgrimages, a fundamental precursor to modern tourism, motivate tourists solely through religious practices. Religious tourism is particularly popular in France, India, Italy and Saudi Arabia. For instance, the Hindu pilgrimage and festival Kumbh Mela in India, inscribed in 2017 on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, attracts over 120 million pilgrims of all castes, creeds and genders. The festival is held in the cities of Allahabad, Haridwar, Ujjain and Nasik every four years by rotation. Sacred and ceremonial sites have unique significance for peoples and communities, and are often integral to journeys that promote spiritual well-being. Mongolia, for example, has around 800 sacred sites including 10 mountains protected by Presidential Decree, and lakes and ovoos, many of which have their own sutras. In the case of Mongolia, the environmental stewardship and rituals and practices connected with these sacred places also intersects with longstanding political traditions and State leadership.

Cities with a vibrant cultural scene and assets are not only more likely to attract tourists, but also the skilled talent who can advance the city’s long-term prospects. Several cities are also focusing on developing their night-time economies through the promotion of theatre, concerts, festivals, light shows and use of public spaces that increasingly making use of audio-visual technologies. Situated on Chile’s Pacific coast, the city of Valparaíso, a World Heritage site, is taking steps to transform the city’s night scene into a safe and inclusive tourist destination through revitalizing public spaces. While the economies of many cities have been weakened during the pandemic, the night-time economy of the city of Chengdu in China, a UNESCO Creative City for Gastronomy, has flourished and has made a significant contribution to generating revenue for the city, accounting for 45% of citizen’s daily expenditure.

The pandemic has generated the public’s re-appropriation of the urban space. People have sought open-air sites and experiences in nature. In many countries that are experiencing lockdowns, public spaces, including parks and city squares, have proven essential for socialization and strengthening resilience. People have also reconnected with the heritage assets in their urban environments. Local governments, organizations and civil society have introduced innovative ways to connect people and encourage creative expression. Cork City Council Arts Office and Creative Ireland, for example, jointly supported the art initiative Ardú- Irish for ‘Rise’ – involving seven renowned Irish street artists who produced art in the streets and alleyways of Cork.

Chengdu Town Square, China by Lukas Bischoff

Environment-based solutions support integrated approaches to deliver across the urban-rural continuum, and enhance visitor experiences by drawing on the existing features of a city. In the city of Bamberg, a World Heritage site in Germany, gardens are a key asset of the city and contribute to its livability and the well-being of its local population and visitors. More than 12,000 tourists enjoy this tangible testimony to the local history and environment on an annual basis. Eighteen agricultural businesses produce local vegetables, herbs, flowers and shrubs, and farm the inner-city gardens and surrounding agricultural fields. The museum also organizes gastronomic events and cooking classes to promote local products and recipes.

In rural areas, crafts can support strategies for cultural and community-based tourism. This is particularly the case in Asia, where craft industries are often found in rural environments and can be an engine for generating employment and curbing rural-urban migration. Craft villages have been established in Viet Nam since the 11th century, constituting an integral part of the cultural resources of the country, and whose tourism profits are often re-invested into the sustainability of the villages. The craft tradition is not affected by heavy tourist seasons and tourists can visit all year round.

Indigenous tourism can help promote and maintain indigenous arts, handicrafts, and culture, including indigenous culture and traditions, which are often major attractions for visitors. Through tourism, indigenous values and food systems can also promote a less carbon-intensive industry. During COVID-19, the Government of Canada has given a series of grants to indigenous tourism businesses to help maintain livelihoods. UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions announced that it will grant, through the International Fund for Creative Diversity (IFCD), US$70,000 dollars to Mexican indigenous cultural enterprises, which will support indigenous enterprises through training programmes, seed funding, a pre-incubation process and the creation of an e-commerce website.

Tourism has boosted community pride in living heritage and the active involvement of local communities in its safeguarding. Local authorities, cultural associations, bearers and practitioners have made efforts to safeguard and promote elements as they have understood that not only can these elements strengthen their cultural identity but that they can also contribute to tourism and economic development. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the role of intellectual property and in the regulation of heritage. In the field of gastronomy, a lot of work has been done in protecting local food products, including the development of labels and certification of origin. Member States are exploring the possibilities of geographical indication (GI) for cultural products as a way of reducing the risk of heritage exploitation in connection to, for example, crafts, textiles and food products, and favouring its sustainable development.

The pandemic has brought to the forefront the evolving role of museums and their crucial importance to the life of societies in terms of health and well-being, education and the economy. A 2019 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) examined 3,000 studies on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being, which indicated that the arts play a major role in preventing, managing and treating illness. Over the past decade the number of museums has increased by 60%, demonstrating the important role that museums have in national cultural policy. Museums are not static but are rather dynamic spaces of education and dialogue, with the potential to boost public awareness about the value of cultural and natural heritage, and the responsibility to contribute to its safeguarding.

Data presented in UNESCO's report "Museums Around the World in the Face of COVID-19" in May 2020 show that 90% of institutions were forced to close, whereas the situation in September-October 2020 was much more variable depending on their location in the world. Large museums have consistently been the most heavily impacted by the drop in international tourism – notably in Europe and North America. Larger museums, such as Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum have reported losses between €100,000 and €600,000 a week. Smaller museums have been relatively stable, as they are not as reliant on international tourism and have maintained a closer connection to local communities. In November, the Network of European Museum Organisations (NEMO) released the results of a survey of 6,000 museums from 48 countries. Of the responding museums, 93% have increased or started online services during the pandemic. Most larger museums (81%) have increased their digital capacities, while only 47% of smaller museums indicated that they did. An overwhelming majority of respondents (92.9%) confirm that the public is safe at their museum. As reported in the Tracker last October, the world’s most visited museum, the Louvre in France (9.3 million visitors annually) witnessed a ten-fold increase in traffic to its website. Yet while digital technologies have provided options for museums to remain operational, not all have the necessary infrastructure, which is the case for many museums in Africa and SIDS.

New technologies have enabled several new innovations that can better support cultural tourism and digital technologies in visitor management, access and site interpretation. Cultural tourists visiting cultural heritage sites, for example, can enjoy educational tools that raise awareness of a site and its history. Determining carrying capacity through algorithms has helped monitor tourist numbers, such as in Hạ Long Bay in Viet Nam. In response to the pandemic, Singapore’s Asian Civilizations Museum is one of many museums that has harnessed digital technologies to provide virtual tours of its collections, thus allowing viewers to learn more about Asian cultures and histories. The pandemic has enhanced the need for technology solutions to better manage tourism flows at destinations and encourage tourism development in alternative areas.

Shaping a post-pandemic vision : regenerative and inclusive cultural tourism

As tourism is inherently dependent on the movement and interaction of people, it has been one of the hardest-hit sectors by the pandemic and may be one of the last to recover. Travel and international border restrictions have led to the massive decline in tourism in 2020, spurring many countries to implement strategies for domestic tourism to keep economies afloat. Many cultural institutions and built and natural heritage sites have established strict systems of physical distancing and hygiene measures, enabling them to open once regulations allow. Once travel restrictions have been lifted, it will enable the recovery of the tourism sector and for the wider economy and community at large.

While the pandemic has dramatically shifted the policy context for cultural tourism, it has also provided the opportunity to experiment with integrated models that can be taken forward in the post-pandemic context. While destinations are adopting a multiplicity of approaches to better position sustainability in their plans for tourism development, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

A comprehensive, integrated approach to the cultural sector is needed to ensure more sustainable cultural tourism patterns. Efforts aimed at promoting cultural tourism destinations should build on the diversity of cultural sub-sectors, including cultural and heritage sites, museums, but also the creative economy and living heritage, notably local practices, food and crafts production. Beyond cultural landmarks, which act as a hotspot to drive the attractiveness of tourism destinations, and particularly cities, cultural tourism should also encompass other aspects of the cultural value chain as well as more local, community-based cultural expressions. Such an integrated approach is likely to support a more equitable distribution of cultural tourism revenues, also spreading tourism flows over larger areas, thus curbing the negative impacts of over-tourism on renowned cultural sites, including UNESCO World Heritage sites. This comprehensive vision also echoes the growing aspiration of visitors around the world for more inclusive and sustainable tourism practices, engaging with local communities and broadening the understanding of cultural diversity.

As a result of the crisis, the transversal component of cultural tourism has been brought to the fore, demonstrating its cross-cutting nature and alliance with other development areas. Cultural tourism – and tourism more broadly – is highly relevant to the 2030 for Sustainable Development and its 17 SDGs, however, the full potential of cultural tourism for advancing development – economic, social and environmental - remains untapped. This is even though cultural tourism is included in a third of all countries’ VNRs, thus demonstrating its priority for governments. Due the transversal nature of cultural tourism, there is scope to build on these synergies and strengthen cooperation between ministries to advance cooperation for a stronger and more resilient sector. This plays an integral role in ensuring a regenerative and inclusive cultural tourism sector. Similarly, tourism can feature as criteria for certain funding initiatives, or as a decisive component for financing cultural projects, such as in heritage or the cultural and creative industries.

Houses in Amsterdam, adisa, Getty, Images Pro

Several countries have harnessed the crisis to step up actions towards more sustainable models of cultural tourism development by ensuring that recovery planning is aligned with key sustainability principles and the SDGs. Tourism both impacts and is impacted by climate change. There is scant evidence of integration of climate strategies in tourism policies, as well as countries’ efforts to develop solid crisis preparedness and response strategies for the tourism sector. The magnitude and regional variation of climate change in the coming decades will continue to affect cultural tourism, therefore, recovery planning should factor in climate change concerns. Accelerating climate action is of utmost importance for the resilience of the sector.

The key role of local actors in cultural tourism should be supported and developed. States have the opportunity to build on local knowledge, networks and models to forge a stronger and more sustainable cultural tourism sector. This includes streamlining cooperation between different levels of governance in the cultural tourism sector and in concert with civil society and private sector. Particularly during the pandemic, many cities and municipalities have not received adequate State support and have instead introduced measures and initiatives using local resources. In parallel, such actions can spur new opportunities for employment and training that respond to local needs.

Greater diversification in cultural tourism models is needed, backed by a stronger integration of the sector within broader economic and regional planning. An overdependence of the cultural sector on the tourism sector became clear for some countries when the pandemic hit, which saw their economies come to a staggering halt. This has been further weakened by pre-existing gaps in government and industry preparedness and response capacity. The cultural tourism sector is highly fragmented and interdependent, and relies heavily on micro and small enterprises. Developing a more in-depth understanding of tourism value chains can help identify pathways for incremental progress. Similarly, more integrated – and balanced – models can shape a more resilient sector that is less vulnerable to future crises. Several countries are benefiting from such approaches by factoring in a consideration of the environmental and socio-cultural pillars of sustainability, which is supported across all levels of government and in concert with all stakeholders.

abhishek gaurav, Pexels

Inclusion must be at the heart of building back better the cultural tourism sector. Stakeholders at different levels should participate in planning and management, and local communities cannot be excluded from benefitting from the opportunities and economic benefits of cultural tourism. Moreover, they should be supported and empowered to create solutions from the outset, thus forging more sustainable and scalable options in the long-term. Policy-makers need to ensure that cultural tourism development is pursued within a wider context of city and regional strategies in close co-operation with local communities and industry. Businesses are instrumental in adopting eco-responsible practices for transport, accommodation and food. A balance between public/ private investment should also be planned to support an integrated approach post-crisis, which ensures input and support from industry and civil society.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the essential role of museums as an integral component of societies in terms of well-being, health, education and the economy. Digitalization has been a game-changer for many cultural institutions to remain operational to the greatest extent possible. Yet there are significant disparities in terms of infrastructure and resources, which was underscored when the world shifted online. Museums in SIDS have faced particular difficulties with lack of access to digitalization. These imbalances should be considered in post-crisis strategies.

The pandemic presents an occasion to deeply rethink tourism for the future, and what constitutes the markers and benchmarks of “success”. High-quality cultural tourism is increasingly gaining traction in new strategies for recovery and revival, in view of contributing to the long-term health and resilience of the sector and local communities. Similarly, many countries are exploring ways to fast track towards greener, more sustainable tourism development. As such, the pandemic presents an opportunity for a paradigm shift - the transformation of the culture and tourism sectors to become more inclusive and sustainable. Moreover, this includes incorporating tourism approaches that not only avoid damage but have a positive impact on the environment of tourism destinations and local communities. This emphasis on regenerative tourism has a holistic approach that measures tourism beyond its financial return, and shifts the pendulum towards focusing on the concerns of local communities, and the wellbeing of people and planet.

Entabeni Game Reserve in South Africa by SL_Photography

Related items

More on this subject.

Other recent news

Take advantage of the search to browse through the World Heritage Centre information.

Sustainable Tourism

UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme

The UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme represents a new approach based on dialogue and stakeholder cooperation where planning for tourism and heritage management is integrated at a destination level, the natural and cultural assets are valued and protected, and appropriate tourism developed.

World Heritage and tourism stakeholders share responsibility for conservation of our common cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value and for sustainable development through appropriate tourism management.

Facilitate the management and development of sustainable tourism at World Heritage properties through fostering increased awareness, capacity and balanced participation of all stakeholders in order to protect the properties and their Outstanding Universal Value.

Focus Areas

Policy & Strategy

Sustainable tourism policy and strategy development.

Tools & Guidance

Sustainable tourism tools

Capacity Building

Capacity building activities.

Heritage Journeys

Creation of thematic routes to foster heritage based sustainable tourism development

A key goal of the UNESCO WH+ST Programme is to strengthen the enabling environment by advocating policies and frameworks that support sustainable tourism as an important vehicle for managing cultural and natural heritage. Developing strategies through broad stakeholder engagement for the planning, development and management of sustainable tourism that follows a destination approach and focuses on empowering local communities is central to UNESCO’s approach.

Supporting Sustainable Tourism Recovery

Enhancing capacity and resilience in 10 World Heritage communities

Supported by BMZ, and implemented by UNESCO in collaboration with GIZ, this 2 million euro tourism recovery project worked to enhance capacity building in local communities, improve resilience and safeguard heritage.

Policy orientations

Defining the relationship between world heritage and sustainable tourism

Based on the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009), the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session adopted the policy orientations which define the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Decision 34 COM 5F.2 ).

World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate

Providing an overview of the increasing vulnerability of World Heritage sites to climate change impacts and the potential implications for and of global tourism.

Sustainable Tourism Tools

Manage tourism efficiently, responsibly and sustainably based on the local context and needs

People Protecting Places is the public exchange platform for the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme, providing education and information, encouraging support, engaging in social and community dialogue

The ' How-To ' guides offer direction and guidance to managers of World Heritage tourism destinations and other stakeholders to help identify the most suitable solutions for circumstances in their local environments and aid in developing general know-how.

English French Russian

Helping site managers and other tourism stakeholders to manage tourism more sustainably

Capacity Building in 4 Africa Nature Sites

A series of practical training and workshops were organized in four priority natural World Heritage sites in Africa (Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) with the aim of providing capacity building tools and strategies for site managers to help them manage tourism at their sites more sustainably.

Learn more →

15 Pilot Sites in Nordic-Baltic Region

The project Towards a Nordic-Baltic pilot region for World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism (2012-2014) was initiated by the Nordic World Heritage Foundation (NWHF). With a practical approach, the project has contributed to tools for assessing and developing sustainable World Heritage tourism strategies with stakeholder involvement and cooperation.

Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia

Entitled “The Power of Culture: Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia", the UNESCO Office in Jakarta with the technical assistance of the UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme and the support from the Government of Malaysia is spearheading the first regional effort in Southeast Asia to introduce a new approach to sustainable tourism management at World Heritage sites in Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

Cultural tourism is one of the largest and fastest-growing global tourism markets. Culture and creative industries are increasingly being used to promote destinations and enhance their competitiveness and attractiveness.

Many locations are now actively developing their cultural assets as a means of developing comparative advantages in an increasingly competitive tourism marketplace, and to create local distinctiveness in the face of globalization.

UNESCO will endeavour to create networks of key stakeholders to coordinate the destination management and marketing associated with the different heritage routes to promote and coordinate high-quality, unique experiences based on UNESCO recognized heritage. The goal is to promote sustainable development based on heritage values and create added tourist value for the sites.

UNESCO World Heritage Journeys of the EU

Creating heritage-based tourism that spurs investment in culture and the creative industries that are community-centered and offer sustainable and high-quality products that play on Europe's comparative advantages and diversity of its cultural assets.

World Heritage Journeys of Buddhist Heritage Sites

UNESCO is currently implementing a project to develop a unique Buddhist Heritage Route for Sustainable Tourism Development in South Asia with the support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). South Asia is host to rich Buddhist heritage that is exemplified in the World Heritage properties across the region.

Programme Background

In 2011 UNESCO embarked on developing a new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme.

The aim was to create an international framework for the cooperative and coordinated achievement of shared and sustainable outcomes related to tourism at World Heritage properties.

The preparatory work undertaken in developing the Programme responded to the decision 34 COM 5F.2 of the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session in Brasilia in 2010, which requested

“the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to the implementation of this programme".

The Steering Group was comprised of States Parties representatives from the six UNESCO Electoral Groups (Germany (I), Slovenia (II), Argentina (III), China (IV), Tanzania (Va), and Lebanon (Vb)), the Director of the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS and ICCROM), the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the Swiss Government as the donor agency.

The Government of Switzerland has provided financial support for specific actions to be undertaken by the Steering Group. To coordinate and support the process, the World Heritage Centre has formed a small Working Group with the support of the Nordic World Heritage Foundation, the Government of Switzerland and the mandated external consulting firm MartinJenkins.

The World Heritage Committee directed that the Programme take into account:

- the recommendations of the evaluation of the concluded tourism programme ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3 )

- the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism that emerged from the workshop Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 )

Overarching and strategic processes that the new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme will be aligned with include the Strategic Objectives of the World Heritage Convention (the five C's) ( Budapest Declaration 2002 ), the ongoing Reflections on the Future of the World Heritage Convention ( WHC-11/35.COM/12A ) and the Strategic Action Plan for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention 2012-2022 ( WHC-11/18.GA/11 ), the Relationship between the World Heritage Convention and Sustainable Development (WHC-10/34.COM/5D), the World Heritage Capacity Building Strategy ( WHC-10/34.COM/5D ), the Global Strategy for a Representative, Balanced and Credible World Heritage List (1994), and the Evaluation of the Global Strategy and PACT initiative ( WHC-11/18.GA/8 - 2011 ).

In addition, the programme development process has been enriched by an outreach to representatives from the main stakeholder groups including the tourism sector, national and local governments, site practitioners and local communities. The programme design was further developed at an Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadine, Switzerland October 2011. In this meeting over 40 experts from 23 countries, representing the relevant stakeholder groups, worked together to identify the overall strategic approach and a prioritised set of key objectives and activities. The proposed Programme was adopted by the World Heritage Committee in 2012 at its 36th session in St Petersburg, Russian Federation .

International Instruments

International Instruments Relating to Sustainable Development and Tourism.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations, charters adopted by ICOMOS, decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee, legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations

- Report by the Department of Economics and Social Affairs: Tourism and Sustainable Development: The Global Importance of Tourism at the United Nations’ Commission on Sustainable Development 7th Session (1999)

- Resolution A/RES/56/212 and the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism adopted by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (1999)

Charters adopted by ICOMOS

- The ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999)

- The ICOMOS Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites (2008)

Decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee

- Decision (XVII.4-XVII.12) adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 25th Session in Helsinki (2001)

- Decision 33 COM 5A adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 30th Session in Seville (2009)

- Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 34th Session in Brasilia (2010)

- Decision 36 COM 5E adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 36th Session in Saint Petersburg (2012)

Legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation in chronological order

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970)

- The Recommendation for the Protection of Movable Cultural Property (1978)

- The Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore (1989)

- The Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural heritage (2001)

- The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005)

Other instruments

- Other instruments OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2012 (French forthcoming)

- Programme on Sustainable Consumption and Production (In English)

- Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture 2015 – Building a New Partnership Model

Decisions / Resolutions (5)

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A,

- Recalling Decision 41 COM 5A adopted at its 41st session (Krakow, 2017) and Decision 40 COM 5D adopted at its 40th session (Istanbul/UNESCO, 2016), General:

- Takes note with appreciation of the activities undertaken by the World Heritage Centre over the past year in pursuit of the Expected Result to ensure that “tangible heritage is identified, protected, monitored and sustainably managed by Member States, in particular through the effective implementation of the 1972 Convention ”, and the five strategic objectives as presented in Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A;

- Welcomes the proactive role of the Secretariat for enhancing synergies between the World Heritage Convention and the other Culture and Biodiversity-related Conventions, particularly the integration of relevant synergies aspects in the revised Periodic Reporting Format and the launch of a synergy-related web page on the Centre’s website;

- Also welcomes the increased collaboration among the Biodiversity-related Conventions through the Biodiversity Liaison Group and focused activities, including workshops, joint statements and awareness-raising;

- Takes note of the Thematic studies on the recognition of associative values using World Heritage criterion (vi) and on interpretation of sites of memory, funded respectively by Germany and the Republic of Korea and encourages all States Parties to take on board their findings and recommendations, in the framework of the identification of sites, as well as management and interpretation of World Heritage properties;

- Noting the discussion paper by ICOMOS on Evaluations of World Heritage Nominations related to Sites Associated with Memories of Recent Conflicts, decides to convene an Expert Meeting on sites associated with memories of recent conflicts to allow for both philosophical and practical reflections on the nature of memorialization, the value of evolving memories, the inter-relationship between material and immaterial attributes in relation to memory, and the issue of stakeholder consultation; and to develop guidance on whether and how these sites might relate to the purpose and scope of the World Heritage Convention , provided that extra-budgetary funding is available and invites the States Parties to contribute financially to this end;

- Also invites the States Parties to support the activities carried out by the World Heritage Centre for the implementation of the Convention ;

- Requests the World Heritage Centre to present, at its 43rd session, a report on its activities. Thematic Programmes:

- Welcomes the progress report on the implementation of the World Heritage Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, notes their important contribution towards implementation of the Global Strategy for representative World Heritage List, and thanks all States Parties, donors and other organizations for having contributed to achieving their objectives;

- Acknowledges the results achieved by the World Heritage Cities Programme and calls States Parties and other stakeholders to provide human and financial resources ensuring the continuation of this Programme in view of its crucial importance for the conservation of the urban heritage inscribed on the World Heritage List, for the implementation of the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape and its contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to cities as well as for its contribution to the preparation of the New Urban Agenda, and further thanks to China and Croatia for their support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Also acknowledges the results achieved of the World Heritage Marine Programme, also thanks Flanders, France and the Annenberg Foundation for their support, notes the increased focus of the Programme on a global managers network, climate change adaptation strategies and sustainable fisheries, and invites States Parties, the World Heritage Centre and other stakeholders to continue to provide human and financial resources to support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Further acknowledges the results achieved in the implementation of the World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme, in particular the development of the Sustainable Tourism and Visitor Management Assessment tool and encourages States Parties to participate in the pilot testing of the tool, expresses appreciation for the funding provided by the European Commission and further thanks the Republic of Korea, Norway, and Seabourn Cruise Line for their support in the implementation of the Programme’’s activities;

- Further notes the progress in the implementation of the Small Island Developing States Programme, its importance for a representative, credible and balanced World Heritage List and building capacity of site managers and stakeholders to implement the World Heritage Convention , thanks furthermore Japan and the Netherlands for their support as well as the International Centre on Space Technology for Natural and Cultural Heritage (HIST) and the World Heritage Institute of Training & Research for the Asia & the Pacific Region (WHITRAP) as Category 2 Centres for their technical and financial supports and also requests the States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to provide human, financial and technical resources for the implementation of the Programme;

- Takes note of the activities implemented jointly by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and ICOMOS under the institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, in line with its Decision 40 COM 5D, further requests the World Heritage Centre to disseminate among the States Parties the second volume of the IAU/ICOMOS Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage and renames this initiative as Initiative on Heritage of Astronomy, Science and Technology;

- Also takes note of the progress report on the Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest, endorses the recommendations of the Thematic Expert Consultation meetings focused on Mediterranean and South-Eastern Europe (UNESCO, 2016), Asia-Pacific (Thailand, 2017) and Eastern Europe (Armenia, 2018), thanks the States Parties for their generous contribution and reiterates its invitation to States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to support this Initiative, as well as its associated Marketplace projects developed by the World Heritage Centre;

- Takes note of the activities implemented by CRATerre in the framework of the World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme, under the overall institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, and of the lines of action proposed for the future, if funding is available;

- Invites States Parties, international organizations and donors to contribute financially to the Thematic Programmes and Initiatives as the implementation of thematic priorities is no longer feasible without extra-budgetary funding;

- Requests furthermore the World Heritage Centre to submit an updated result-based report on Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, under Item 5A: Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 44th session in 2020.

1. Having examined document WHC-12/36.COM/5E,

2. Recalling Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted at its 34th session (Brasilia, 2010),

3. Welcomes the finalization of the new and inclusive Programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism and notes with appreciation the participatory process for its development, objectives and approach towards implementation;

4. Also welcomes the contribution of the Steering Group comprised of States Parties representatives from the UNESCO Electoral Groups, the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS, ICCROM), Switzerland and the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) in the elaboration of the Programme;

5. Thanks the Government of Switzerland, the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for their technical and financial support to the elaboration of the Programme;

6. Notes with appreciation the contribution provided by the States Parties and other consulted stakeholders during the consultation phase of the Programme;

7. Takes note of the results of the Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadin (Switzerland), from 18 to 22 October 2011 contributing to the Programme, and further thanks the Government of Switzerland for hosting the Expert Meeting;

8. Adopts the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

9. Requests the World Heritage Centre to refine the Draft Action Plan 2013-2015 in an Annex to the present document and to implement the Programme with a Steering Group comprised of representatives of the UNESCO Electoral Groups, donor agencies, the Advisory Bodies, UNWTO and in collaboration with interested stakeholders;

10. Notes that financial resources for the coordination and implementation of the Programme do not exist and also requests States Parties to support the implementation of the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

11. Further requests the World Heritage Centre to report biennially on the progress of the implementation of the Programme;

12. Notes with appreciation the launch of the Programme foreseen at the 40th Anniversary of the World Heritage Convention event in Kyoto, Japan, in November 2012

1. Having examined Document WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 and WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3,

2. Highlighting that the global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures, and the relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two way: tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties and can contribute to cross-cultural exchange but, if not managed well, poses challenges to these properties and recognizing the increasing challenges and opportunities relating to tourism;

3. Expresses its appreciation to the States Parties of Australia, China, France, India, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, and to the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for the financial and technical support to the World Heritage Tourism Programme since its establishment in 2001;

4. Welcomes the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) and adopts the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Attachment A );

5. Takes note of the evaluation of the World Heritage Tourism Programme by the UN Foundation, and encourages the World Heritage Centre to take fully into account the eight programme elements recommended in the draft final report in any future work on tourism ( Attachment B );

6. Decides to conclude the World Heritage Tourism Programme and requests the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to implementation of this programme, drawing on the directions established in the reports identified in Paragraphs 4 and 5 above, for consideration at the 35th session of the World Heritage Committee (2011);

7. Also welcomes the offer of the Government of Switzerland to provide financial and technical support to specific activities supporting the steering group; further welcomes the offer of the Governments of Sweden, Norway and Denmark to organize a Nordic-Baltic regional workshop in Visby, Gotland, Sweden in October 2010 on World Heritage and sustainable tourism; and also encourages States Parties to support the new programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism including through regional events and the publication of materials identifying good practices;

8. Based upon the experience gained under the World Heritage Convention of issues related to tourism, invites the Director General of UNESCO to consider the feasibility of a Recommendation on the relationship between heritage conservation and sustainable tourism.

Attachment A

Recommendations of the international workshop

on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites

Policy orientations: defining the relationship between World Heritage and tourism

1. The tourism sector

The global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures.

Tourists/visitors are diverse in terms of cultural background, interests, behaviour, economy, impact, awareness and expectations of World Heritage.

There is no one single way for the World Heritage Convention , or World Heritage properties, to engage with the tourism sector or with tourists/visitors.

2. The relationship between World Heritage and tourism

The relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two-way:

a. World Heritage offers tourists/visitors and the tourism sector destinations

b. Tourism offers World Heritage the ability to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage properties, and also a means to realise community and economic benefits through sustainable use.

Tourism is critical for World Heritage:

a. For States Parties and their individual properties,

i. to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage

ii. to realise community and economic benefits

b. For the World Heritage Convention as a whole, as the means by which World Heritage properties are experienced by visitors travelling nationally and internationally

c. As a major means by which the performance of World Heritage properties, and therefore the standing of the Convention , is judged,

i. many World Heritage properties do not identify themselves as such, or do not adequately present their Outstanding Universal Value

ii. it would be beneficial to develop indicators of the quality of presentation, and the representation of the World Heritage brand

d. As a credibility issue in relation to: i. the potential for tourism infrastructure to damage Outstanding Universal Value

i. the threat that World Heritage properties may be unsustainably managed in relation to their adjoining communities

ii. sustaining the conservation objectives of the Convention whilst engaging with economic development

iii. realistic aspirations that World Heritage can attract tourism.

World Heritage is a major resource for the tourism sector:

a. Almost all individual World Heritage properties are significant tourism destinations

b. The World Heritage brand can attract tourists/visitors,

i. the World Heritage brand has more impact upon tourism to lesser known properties than to iconic properties.

Tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties:

a. to meet the requirement in Article 4 of the Convention to present World Heritage to current and future generations

b. to realise economic benefits.

Tourism, if not managed well, poses threats to World Heritage properties.

3. The responses of World Heritage to tourism

The impact of tourism, and the management response, is different for each World Heritage property: World Heritage properties have many options to manage the impacts of tourism.

The management responses of World Heritage properties need to:

a. work closely with the tourism sector

b. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

c. include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

While there are many excellent examples of World Heritage properties successfully managing their relationship to tourism, it is also clear that many properties could improve:

a. the prevention and management of tourism threats and impacts

b. their relationship to the tourism sector inside and outside the property

c. their interaction with local communities inside and outside the property

d. their presentation of Outstanding Universal Value and focus upon the experience of tourists/visitors.

a. be based on the protection and conservation of the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, and its effective and authentic presentation

b. work closely with the tourism sector

c. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

d. to include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

4. Responsibilities of different actors in relation to World Heritage and tourism

The World Heritage Convention (World Heritage Committee, World Heritage Centre, Advisory Bodies):

a. set frameworks and policy approaches

b. confirm that properties have adequate mechanisms to address tourism before they are inscribed on the World Heritage List

i. develop guidance on the expectations to be include in management plans

c. monitor the impact upon OUV of tourism activities at inscribed sites, including through indicators for state of conservation reporting

d. cooperate with other international organisations to enable:

i. other international organisations to integrate World Heritage considerations in their programs

ii. all parties involved in World Heritage to learn from the activities of other international organisations

e. assist State Parties and sites to access support and advice on good practices

f. reward best practice examples of World Heritage properties and businesses within the tourist/visitor sector

g. develop guidance on the use of the World Heritage emblem as part of site branding.

Individual States Parties:

a. develop national policies for protection

b. develop national policies for promotion

c. engage with their sites to provide and enable support, and to ensure that the promotion and the tourism objectives respect Outstanding Universal Value and are appropriate and sustainable

d. ensure that individual World Heritage properties within their territory do not have their OUV negatively affected by tourism.

Individual property managers:

a. manage the impact of tourism upon the OUV of properties

i. common tools at properties include fees, charges, schedules of opening and restrictions on access

b. lead onsite presentation and provide meaningful visitor experiences

c. work with the tourist/visitor sector, and be aware of the needs and experiences of tourists/visitors, to best protect the property

i. the best point of engagement between the World Heritage Convention and the tourism sector as a whole is at the direct site level, or within countries

d. engage with communities and business on conservation and development.

Tourism sector:

a. work with World Heritage property managers to help protect Outstanding Universal Value

b. recognize and engage in shared responsibility to sustain World Heritage properties as tourism resources

c. work on authentic presentation and quality experiences.

Individual tourists/visitors with the assistance of World Heritage property managers and the tourism sector, can be helped to appreciate and protect the OUV of World Heritage properties.

Attachment B