Skip to Main Content of WWII

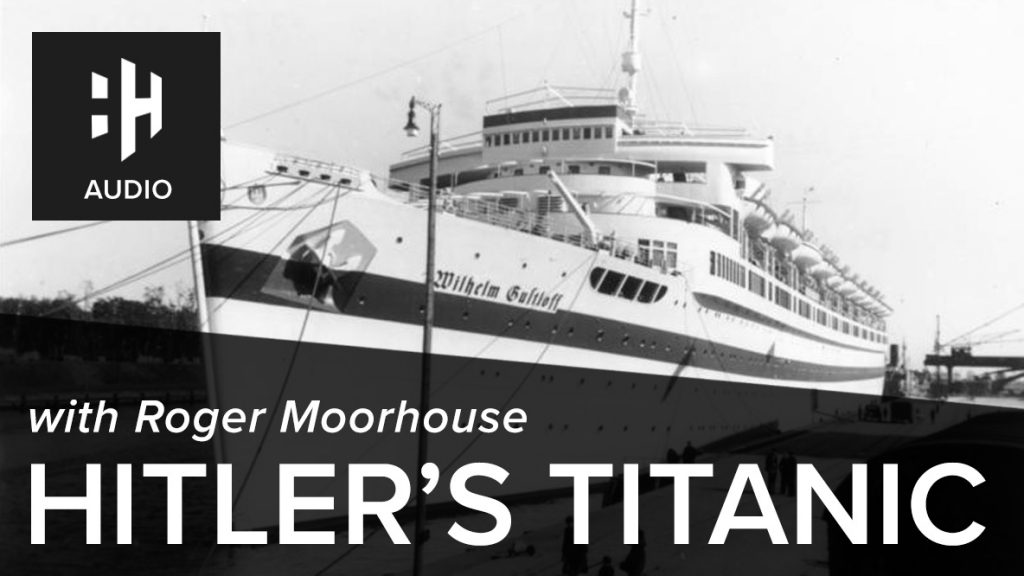

The sinking of the wilhelm gustloff.

A night of horror, and the worst maritime disaster of all time.

World War II is filled with events that can only be described in superlatives: the biggest, the bravest, the fastest, and so on.

And then there is something else World War II is filled with: “worsts.”

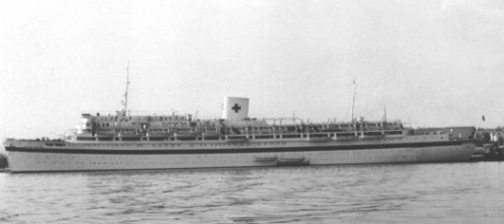

Consider what happened to the German ship Wilhelm Gustloff on the evening of January 30, 1945, seventy-five years ago. Formerly a cruise liner for Hitler's "Strength Through Joy" program in the 1930's, and then a hospital ship during wartime, Wilhelm Gustloff was pulling different duty that long-ago night in the Baltic Sea. It was part of Operation Hannibal, the evacuation of German military personnel and civilian refugees from the ports of East Prussia, now cut off from Germany by the advance of Soviet armies deep into the province of East Prussia.

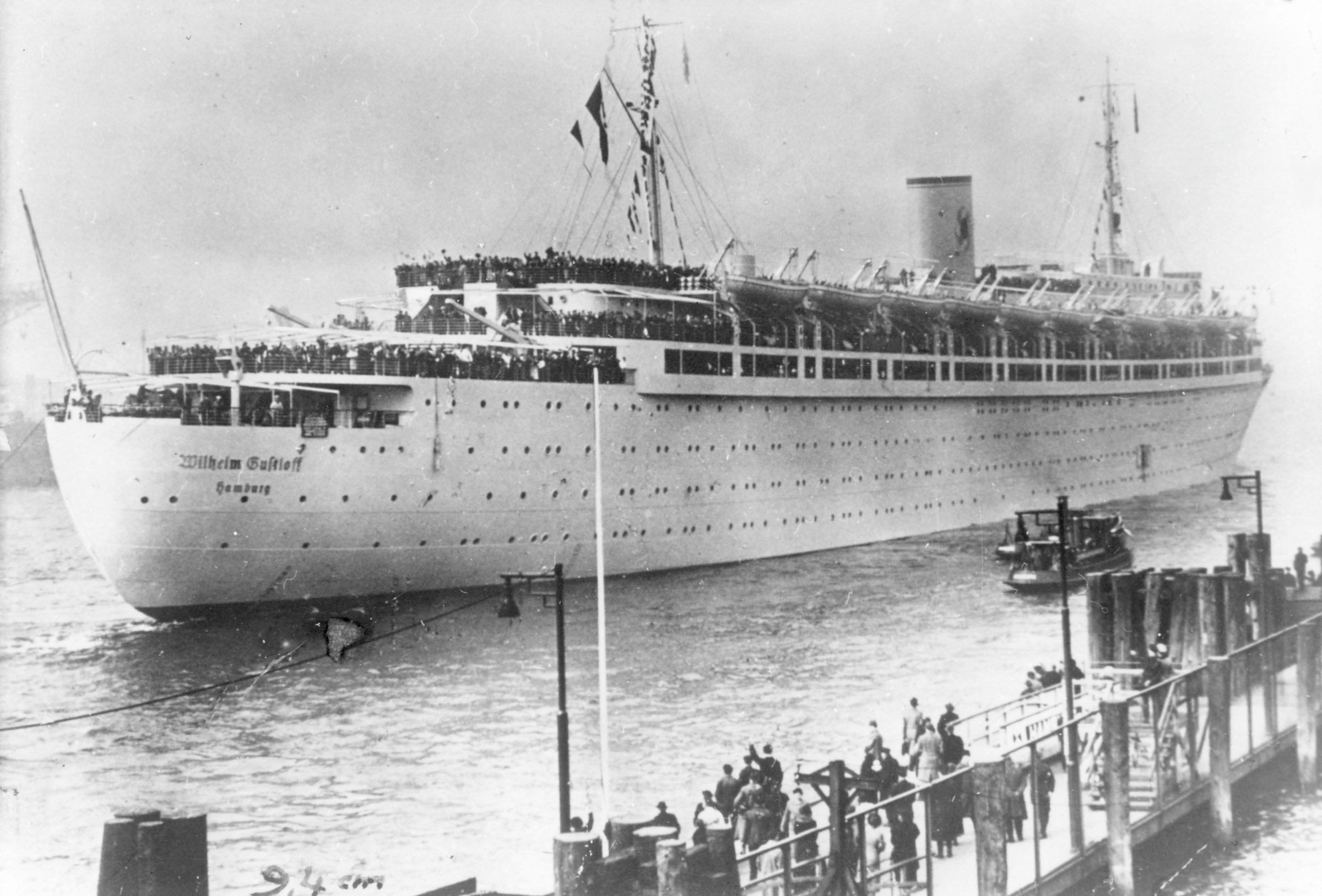

German refugees were on the road in the winter of 1944-45, great columns of men, women, and children, desperate to flee as the onrushing Soviets overran their homes. They were making for the coast, for the safety of the ports Pillau or Gotenhafen. Here, rumor had it, they would be evacuated to the west. The trek was a harrowing one, replete with sub-zero temperatures, blizzards, and Soviet air attacks. This was human misery on a grand scale, reminiscent of what had happened to Soviet civilians during the German invasion of 1941.

When they arrived in Pillau, these refugees found not salvation, but chaos. The last months of the Third Reich featured scenes of unimaginable confusion, and this was no exception. Nazi Party officials haggled with the Navy over who was in charge of Hannibal, about the precise start date, even about who was to be rescued first. The local “Reichs Defense Commissar,” Gauleiter Eric Koch, was an ardent Nazi who didn’t want to appear weak in the eyes of the Führer. He wanted the evacuation postponed as long as possible. Admiral Karl Dönitz felt that the earlier the evacuation took place, the better its chance of success, a reasonable assumption. When trains arrived from Danzig with the families of 500 high ranking Nazis in the civil administration, Koch wanted them prioritized for the evacuation ships, but Dönitz refused. While officials argued, refugees kept pouring into the port, until by mid-January, Pillau was bulging with some 100,000 desperate civilians.

Command squabbles delayed the departure of Wilhelm Gustloff until midday January 30, escorted only by a pair of torpedo boats. Even as it was preparing to depart the harbor, the ship was still picking up more human cargo, another 600 from the steamer Reval , for example. The ship, built to carry a few thousand people, was now bulging with some 7,000-10,000 people, including 4,000-5,000 children. The recorded numbers contradict one another, and we probably never will know how many people were on board the ship.

One thing is certain. Lying in wait in the dark waters of the Baltic Sea was the Soviet submarine S-13 under Captain Alexander Marinesko. As Wilhelm Gustloff steamed slowly to the west, Marinesko shadowed it, then, at 9 pm, fired a spread of four torpedoes. Three of them hit home, striking Wilhelm Gustloff on the bow, stern, and amidships. The jam-packed ship was soon a scene of horror, with explosions, fires, children blown overboard, passengers slipping and sliding on the icy deck, and tumbling into the sea. No help was at hand. Indeed, most of the ship’s actual crew was trapped in the forecastle, behind watertight doors that had locked automatically upon impact.

Not that it would have mattered much. Wilhelm Gustloff sank within an hour. Those who had not been killed by the initial blast or by the chaos on board after the attack froze to death in the icy Baltic. The dead numbered between 6,000-9,000. Once again, the figure depends on the initial figure for those on board. Choose either number, in fact, and the result is the same: even with 1,200 survivors picked up by rescue vessels, the sinking of Wilhelm Gustloff was the worst disaster in maritime history, at least four times bigger, in terms of human life, than the sinking of the Titanic.

Was it a war crime? Charges that Marinesko had violated the laws of war have arisen from time to time, but they’ve been difficult to sustain. He didn’t know he was looking at a refugee ship, and at any rate the presence on board of some 1,000 naval personnel, along with a couple of quad anti-aircraft guns, made Wilhelm Gustloff a legitimate target.

War crime or not, what happened to Wilhelm Gustloff was bad. In fact, we might say it was the worst.

Robert Citino, PhD

Explore further.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

When the Nazis came to clear out the Warsaw Ghetto, they were met with fierce resistance.

Stutthof Concentration Camp and the Death Marches

Stutthof concentration camp was among the sites of horror caught up in this gruesome crescendo to Adolf Hitler’s war for racial supremacy.

Dauntless: A Conversation with WWII Veteran Paul Hilliard

Visitors at the National WWII Museum had the special opportunity to hear from WWII veteran and Museum Trustee Paul Hilliard as he discussed his life story documented in the new biography, Dauntless .

Lee Miller: Witness to the Concentration Camps and the Fall of the Third Reich

One of America’s only women war correspondents reports on the liberation of the concentration camps, Soviet and American troops meeting at Torgau, and Hitler’s burning villa in Berchtesgaden

Lee Miller in Combat

One of America’s only female war correspondents reported on the aftermath of D-Day, the Battle of Saint-Malo, and the liberation of Paris.

Lee Miller: Women at War

One of America’s only female war correspondents captured the war through women’s service.

A Contested Legacy: The Men of Montford Point and the Good War

Despite their commendable service during World War II, the Marines of Montford Point would regularly contend with societal forces that vehemently resisted all measures taken toward racial integration.

Our War Too: Women's History Symposium

The symposium, which took place from February 29 to March 1, 2024, featured topics expanding upon the Museum’s special exhibit, Our War Too: Women in Service .

MilitaryHistoryNow.com

The Premier Online Military History Magazine

The Gustloff Incident – History’s Deadliest (and Mostly Forgotten) Maritime Disaster

The RMS Titanic is by far the most famous ill-fated ship of all time. Yet the unlucky luxury liner, which went down with more than 1,600 on board, can’t touch the doomed Nazi cruise ship Wilhelm Gustloff when it comes to lives lost. Destroyed in action while carrying refugees amid the chaotic closing weeks of World War Two, the German vessel sank with several thousand more passengers than legendary British Cunard Liner. But despite the scope of the tragedy, few in the West know much about the event, which remains hands-down the worst maritime disaster in recorded history. Journalist and historian Cathryn J. Prince, author of the award winning 2013 book Death in the Baltic: The World War II Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff , recently penned this piece about the epic tragedy for MilitaryHistoryNow.com. We’re happy to share it with you.

By Cathryn J. Prince

On Jan. 30, 1945, history’s deadliest maritime disaster in peace or war occurred in the Baltic Sea. An estimated 10,000 people perished in the little-known incident that saw a Soviet submarine torpedo the German cruise ship Wilhelm Gustloff off Leba, Poland.

A Ship Named Gustloff

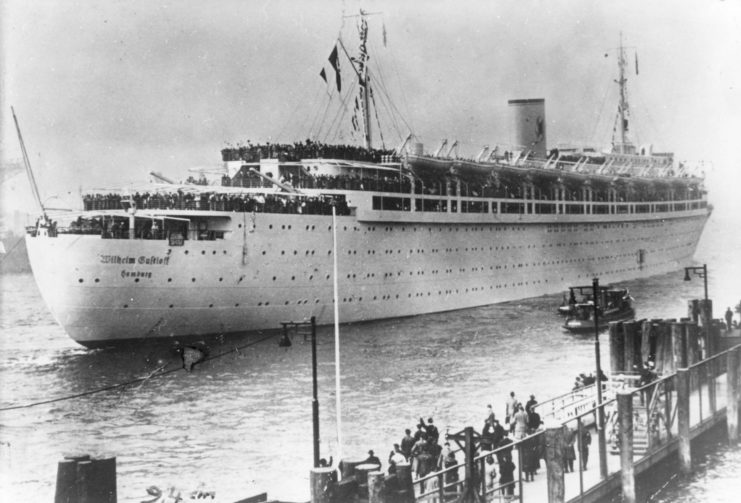

When Adolf Hitler launched the Wilhelm Gustloff from the seaside city of Hamburg on May 5, 1937, hundreds of German workers and Nazi party officials gathered to witness the spectacle.

Flags and swastika banners festooned the quay and arms raised in the notorious Heil Hitler salute as the ship sailed forth showing an uneasy world the full industrial might of Nazi Germany.

The 200-foot long, 25,000-ton vessel was named for Wilhelm Gustloff , the late head of the Swiss Nazi Party who was gunned down a year earlier by a Yugoslavian Jew named David Frankfurter. The Third Reich chose to pay tribute to one of its foremost leaders in the form of the 25-million Reichsmarks flagship for Nazi Germany’s Kraft durch Freude (KdF) or “Strength Through Joy Fleet”.

The KdF was a subsidiary of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront or German Labor Front. Nazi trade union chief Robert Ley , who also had a liner named for him, helped establish the KdF as a means to provide amenities to the German working class and their families.

The Wilhelm Gustloff, like the Robert Ley and other liners in the fleet, was equipped with 22 lifeboats and featured 12 watertight transverse bulkheads. These measures were supposed to make the ship “absolutely secure.” (After the loss of the Titanic in 1912, no ship builder dared call any vessel, especially a cruise liner, “unsinkable.”)

The Skipper

The Wilhelm Gustloff’s maiden voyage took it to the Mediterranean with Captain Lübbe, 58, in command. The vessel had a compliment of 400 to serve an estimated 1,456 passengers. Just one day into the cruise, Lübbe died of a heart attack. A new captain came aboard to take command: Friedrich Peterson. The Wilhelm Gustloff would be his on the fateful night of Jan. 30, 1945.

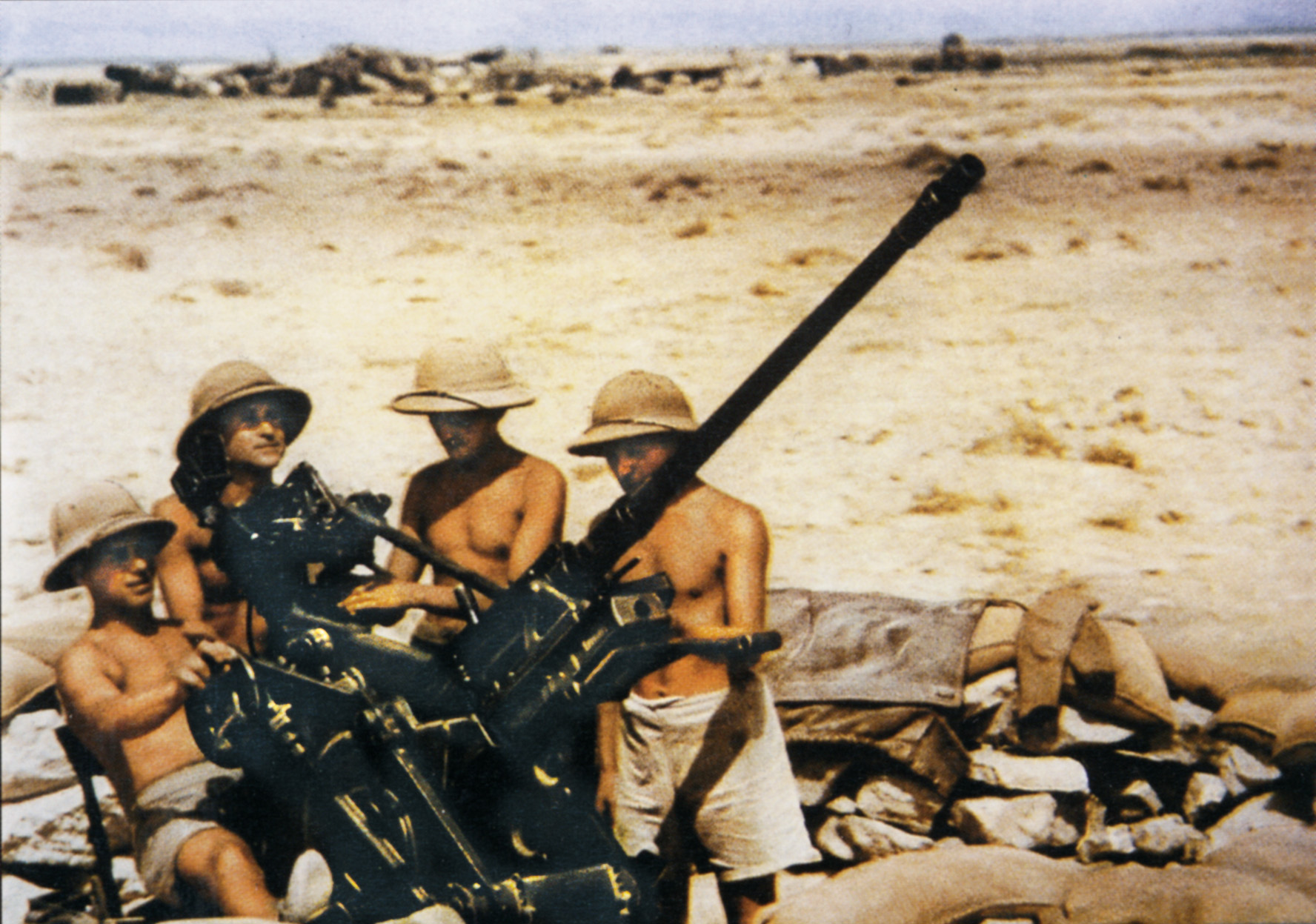

The Soviet Sub Commander

Born in 1913 to a Romanian sailor and a Ukrainian woman, Alexander I. Marinesko was raised in Odessa, a port on the northwest shore of the Black Sea. He joined the Soviet merchant fleet as a young man and later transferred to the navy where moved up through the ranks of that country’s submarine corps. In 1943 he took command of the S-13 , a Russian-built S-Class sub . Although Marinesko enjoyed a successful career as skipper, in early 1945 he faced a court marshal following a forbidden New Year’s Eve tryst with a Swedish national. Desperate to salvage his career, the 32-year-old captain was determined to sink anything German. When he spied the Gustloff in his periscope on the night of Jan. 30, he ordered an attack without hesitation.

Human Cargo

By January 1945, civilians living in Eastern Prussia were growing increasingly frantic. The Red Army was coming and few expected the invaders to offer any quarter to Germans. Fearing the Russian onslaught, Nazi admiral Karl Dönitz commanded his vessels to evacuated as many civilians and military personnel from the region as possible. It would prove to be one of the Kriegsmarine final major efforts of the war. Virtually every available surface ship in the German navy participated in the mission, dubbed Operation Hannibal . Even the Reich’s merchant fleet joined in the boat lift.

The Wilhelm Gustloff was just one of 800 vessels, from mighty cruise liners down to small fishing boats, assigned to carry passengers from the Gulf of Danzig that January. Eventually, more than two million civilians were taken off the Courland, East and West Prussia, Pomerania and parts of Mecklenburg between Jan. 23 and the end of the war in May. Aside from the large ports – Danzig, Gotenhafen, Königsberg, Pillau – throngs of civilians tried their luck from smaller ports and fishing villages.

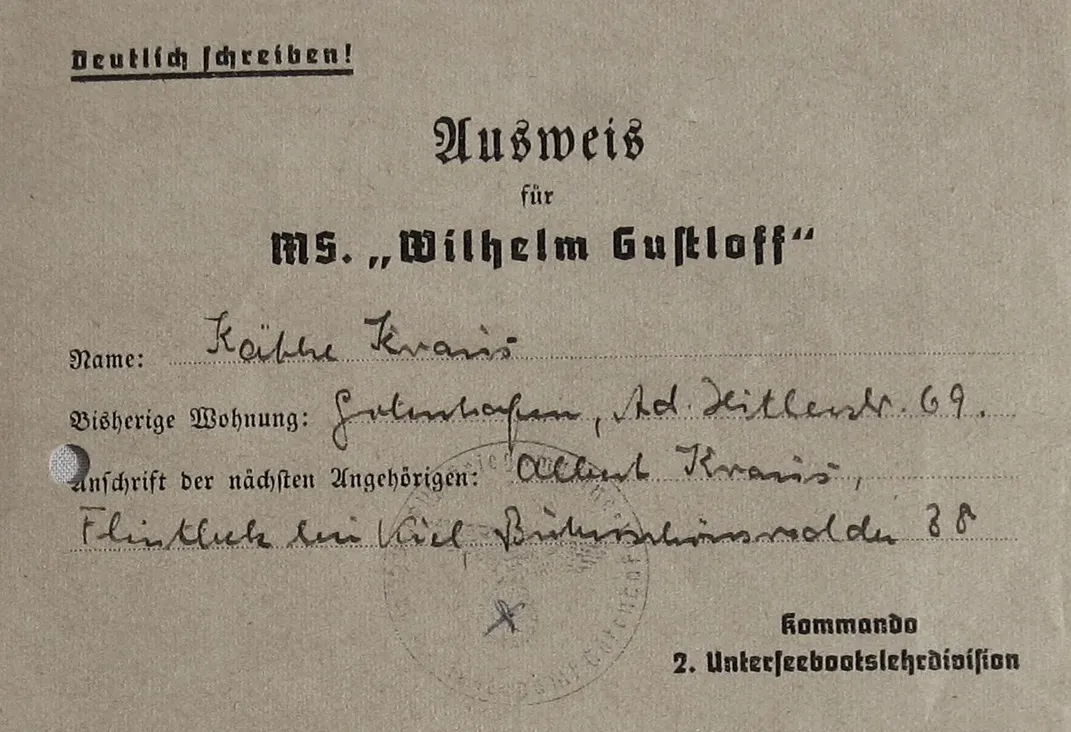

On Jan. 30, more than 10,000 refugees had been crammed aboard Wilhelm Gustloff in Gotenhafen. They hoped the ship would take them to safety in Kiel, a German Naval Base across the Baltic Sea. Shortly after midday, the liner put to see.

Surprise Attack

At around 8 p.m. that same evening, Hitler delivered a speech commemorating the 12th anniversary of the Nazi party’s rise to power. Radio stations throughout the Reich broadcast the event. On board the Wilhelm Gustloff, crewmen transmitted the speech live over the ship-wide PA system.

A short distance away, the commander of the Russian submarine S-13 had spotted the slow-moving liner and moved in for the kill.

At 9 p.m. local time, just as the Fuhrer reached the end of his fevered address, Captain Marinesko ordered the S-13 to fire all four of her tubes at the German vessel. One of the torpedoes became lodged in the launching tube, its primer fully armed. The slightest jolt threatened to detonate the warhead, destroying the submarine. The crew gingerly disarmed the weapon, which had marked with the words “For Stalin”.

The other three torpedoes found their target. The first punched through the bow. The second blasted a hole near the swimming pool where 373 members of the Women’s Naval Auxiliary had taken refuge — most of the young women died instantly. The third torpedo struck the Wilhelm Gustloff amidships, near the engine room. The blast disabled the engines and cut the ship’s power. It also extinguished the lights and silenced the vessel’s communications system.

Over the next 90 minutes, the ship sank.

Today, the Wilhelm Gustloff lies on the sandy bottom of the Baltic Sea. Although the tally of dead and living wouldn’t come until years after the war, it’s now known that fewer than 1,000 survived. Almost six times as many men, women and children perished in the attack than were lost during the April 15, 1912 sinking of the Titanic . And so on Jan. 30, 1945 the Wilhelm Gustloff became the worst maritime disaster in history.

SOURCES Death in the Baltic: The WWII Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff (Palgrave Macmillan).

Help spread the word. Share this article with your friends.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

12 thoughts on “ The Gustloff Incident – History’s Deadliest (and Mostly Forgotten) Maritime Disaster ”

It seems rather callous for the Russians to recognize the event with a postage stamp. Killing 10,000 civilians is hardly an accomplishment worthy of celebration 50 years after the end of the war.

I agree. That’s why I added the image to the article. But to be fair to the Russians, the US issued a stamp in 1995 to commemorate the Enola Gay, much to the unhappiness of Japan.

Those “civilians” consisted mostly of the members of the Nazi auxilary military services. For example, mentioned in this article “children” was Kriegsmarine cadets.

There is always cause and effect (Newton). May be, just may be, the Germans should not have invaded the Soviet Union, not starved 1.2 million civilians at the siege of Leningrad, not starved to death 3 million Russian POWs, not ruined the Ukrainian countryside by burning down farm, carrying off animals, carrying off people turned forced labourers in Germany, not being quite so beastly to Jews, Gypsies, Jehovas Witnesses, etc. They robbed everybody of everything, did they really expect to be treated with kid gloves?

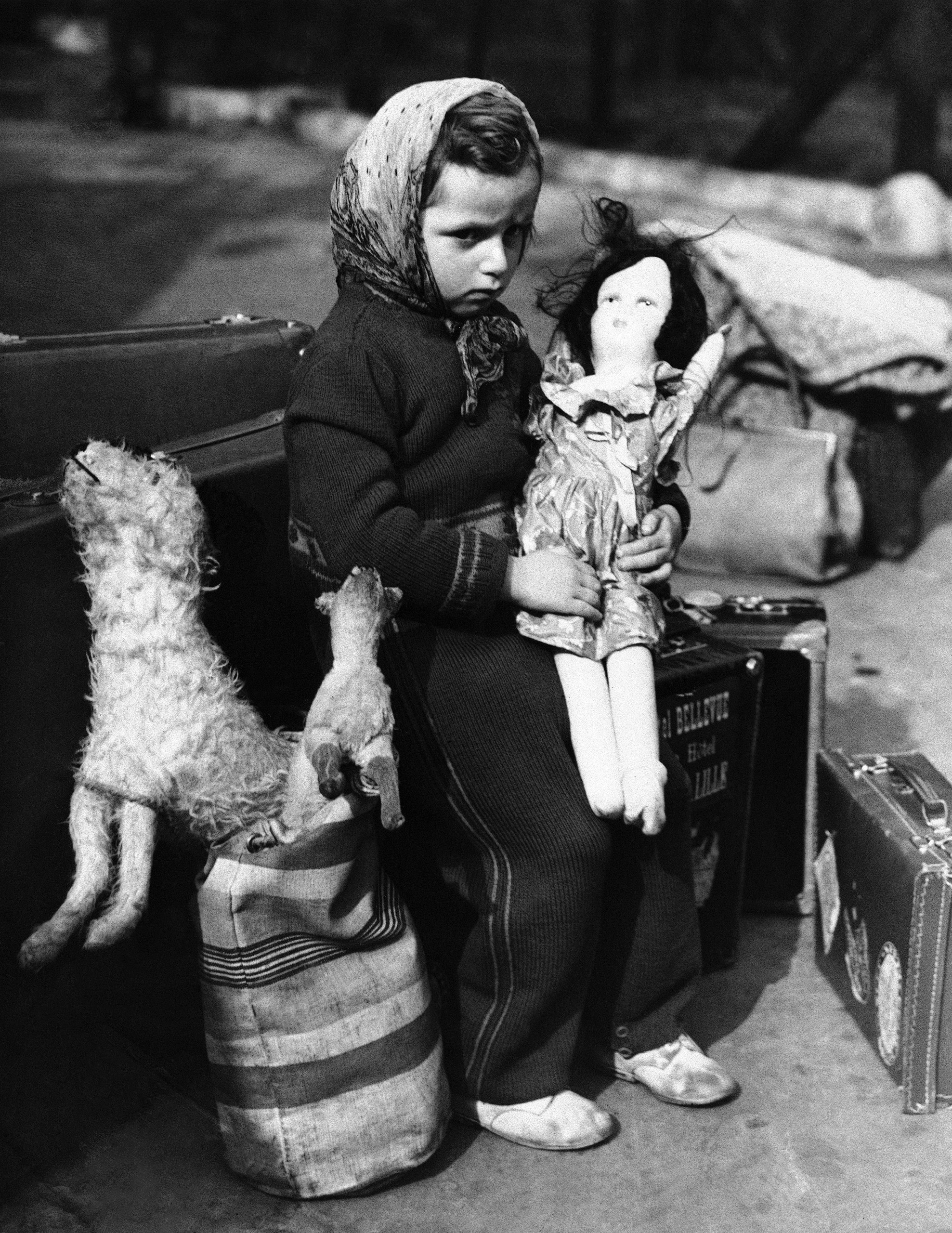

As well as civilians the ship was carrying nearly 1,000 members of the German U-boat training arm, and she was also fitted with light anti-aircraft weapons

At 1945 Gustloff had not been a civilian ship – she was requisitioned by Kriegsmarine in 1939 and was carrying Kriegsmarine colors since 1940.

- Pingback: Episode 459: The MV Wilhelm Gustloff: Hitler's Titanic - Sofa King Podcast

- Pingback: The Ones That Got Away – Seven of Military History’s Most Incredible Evacuations - MilitaryHistoryNow.com

Regardless of a person’s opinions and loyalties – it is always the civilians who suffer from the endless wars waged across the world. In an interview at Nuremberg with Hermann Goring he spoke of how a country’s people were enlisted to support a war, and that it was always the same method throughout history. Tell your people that “our” way of life is in jeopardy because of a perceived enemy.

I would like to politely point out that the Titanic was built and operated and by the White Star Line, not the Cunard Line. May your nights and days be auspicious – thank you.

I would like to politely point out that the Titanic was built, owned and operated by the White Star Line, not the Cunard Line. You were incorrect in the article’s introduction but correct later in the latter part of the article proper. May your nights and days be auspicious. Thank you.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

MHN’s FREE Newsletter

From the MHN Archives

Top Posts & Pages

© COPYRIGHT MilitaryHistoryNow.com

‘The worst maritime disaster ever’: the Sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff

On the night of 30 January 1945, the German ship Wilhelm Gustloff was steaming through the Baltic when three Russian torpedoes slammed into her, sending her to the bottom in a matter of minutes.

Nothing remarkable there. It was wartime and the Russians and Germans had been killing each other since 1941. Only the Wilhelm Gustloff was a passenger liner, not a warship, and she was carrying more than 7,000 non-combatants fleeing the war. All but a few hundred died that night in the largest single loss of life in maritime history.

The Wilhelm Gustloff was part of a massive evacuation of Germans from the Eastern Front in the face of advancing Soviet forces. As German resistance collapsed, Gross Admiral Karl Doenitz organised a seaborne rescue effort code-named ‘Operation Hannibal’ that pressed into service everything still afloat: warships, coastal vessels, former luxury liners, and freighters.

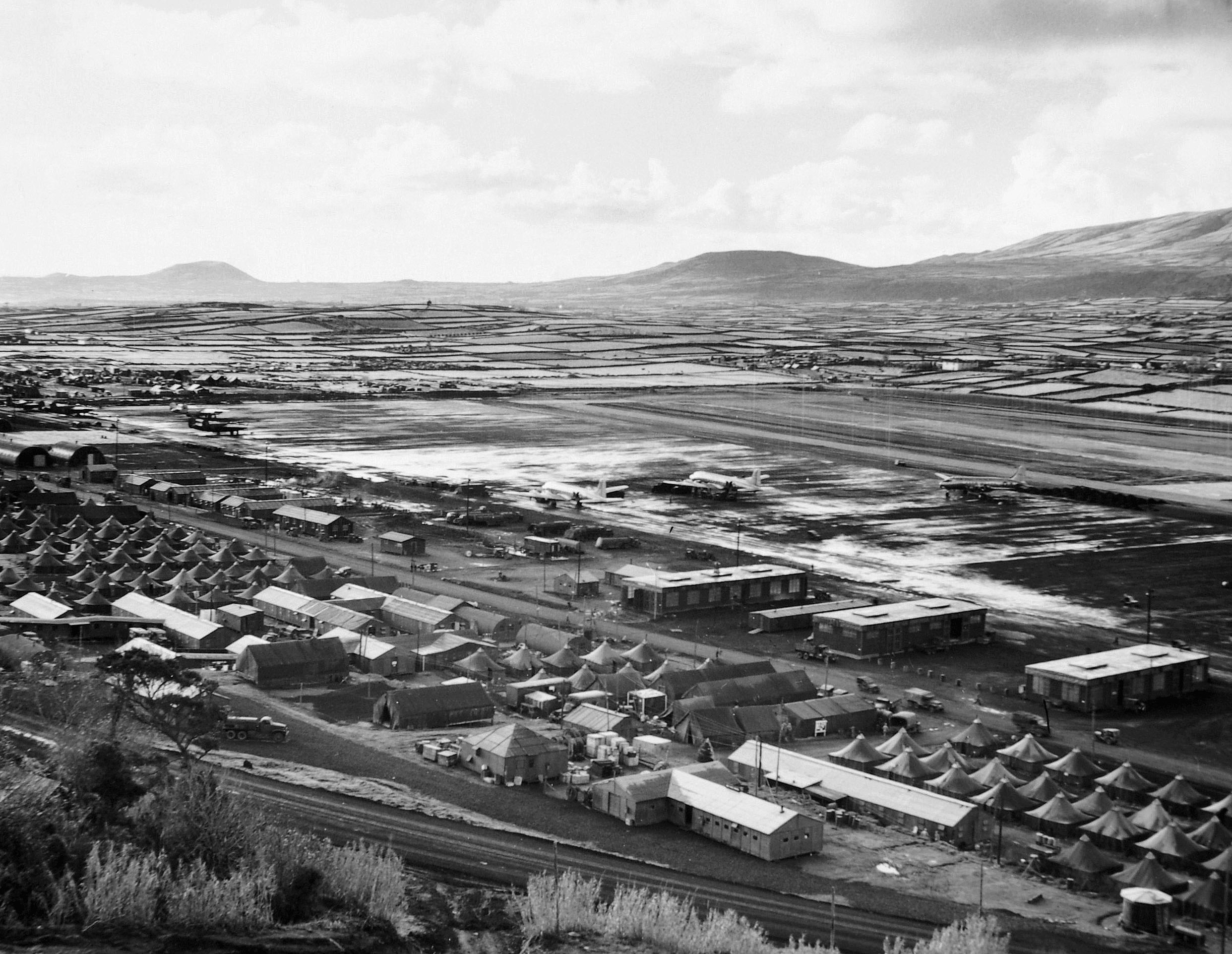

The operation was carried out from a handful of ports around the Gulf of Danzig, including Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland). Hitler had refused to allow Army Group North to conduct an organised retreat, ordering them to dig in and hold ‘fortified places’, theoretically bleeding the Red Army dry. This meant that when the end came it would be a complete collapse.

Tens of thousands of refugees filled German-held ports hoping to escape Russian vengeance for what the Nazis had done in the Soviet Union. Doenitz’s cobbled-together fleet was to make repeated runs between ‘East Sea’ (Baltic) ports and the relative safety of north Germany and Denmark, bringing off as many Germans as possible. It was the Nazi counterpart of Dunkirk, only on a much larger scale. The German high command was particularly determined to save the crews at the submarine-training base in Gotenhafen.

When the evacuation started, the Wilhelm Gustloff had been tied up at the dock for four years, serving as a floating barracks for U-boat trainees. She had not always been so roughly used.

She was originally part of Germany’s ‘Strength Through Joy’ passenger fleet, constructed in the 1930s to show off Nazi shipbuilding, while providing low-cost holiday cruises for the German working classes. The liners would also provide a reserve fleet for the Kriegsmarine in the event of war.

The Wilhelm Gustloff – 25,484 tons displacement, 650 feet long – was launched in 1937 under Hitler’s watchful eye, and named to honour a Swiss ‘martyr’ to National Socialism, assassinated in 1936. She became the flagship of the Strength Through Joy fleet, a seagoing version of the zeppelin Hindenburg.

Early in the war, she served as a hospital ship, bringing the wounded home from the Narvik campaign in Norway. Then she was repainted camouflage grey and turned over to the submarine school for classroom and barracks use, retaining a faint vestige of a large, red swastika on her funnel.

As the Russians closed in on the German coastal enclave in January 1945, the Wilhelm Gustloff was tasked with saving the prized submarine crews, plus as many Nazi functionaries and military personnel as possible.

She operated under an awkward, two-headed command structure, with a veteran merchant-navy captain as master and a young submarine officer in charge of getting her prepped and loaded. From the beginning, these two, Captain Friedrich Petersen and Commander Wilhelm Zahn, did not see eye-to-eye about much of anything.

Preparing to sail

There was a frantic urgency to the preparations, which had to be completed in a matter of hours. Built to carry a maximum of 1,900 passengers and crew, the ship took on at least an additional 5,000, and might have taken even more except that her cabins had been reserved for high-ranking officials and their families. If it had not been winter, still more passengers might have been stowed on her open decks.

The final count included 1,500 submariners (some with families) and 373 Women Naval Auxiliaries, most of them teenagers. The crew set up a special maternity ward for pregnant women, and billeted the Auxiliaries in the empty swimming pool on E Deck.

As word spread that the Wilhelm Gustloff was loading passengers, the docks filled with frantic refugees. Harbour officials issued boarding passes that gave ethnic Germans and parents with small children priority, and posted armed guards at the gangways to keep order. Still, people managed to sneak on by subterfuge and bribery.

Meanwhile, Commander Zahn oversaw the loading of fuel and supplies and the mounting of anti-aircraft guns so the ship would have some hope of defending herself. At the last minute, some mysterious, unmarked crates were loaded into the hold under tight security.

She would be travelling with one other refugee ship, the liner Hansa, plus an escort of two worn-out torpedo-boats and no air cover. The urgency of the preparations meant there was no time to scrounge sufficient lifeboats and life-rafts if the worst came to the worst; she sailed with only 12 of her full complement of 22 lifeboats. But at least everyone was issued a lifejacket. Left unstated was the fact that, because of the cold, lifejackets would be useless if the wearer was in the water more than a few minutes.

Fatal voyage

Wilhelm Gustloff cleared the harbour about midday on 30 January, bound for the Kriegsmarine naval base at Kiel, a relatively short run through mine-filled waters. Shortly after setting out, she learned that her sister-ship, the Hansa, had broken down. Wilhelm Gustloff would be running for her life alone but for her escort of two decrepit torpedo-boats, a sitting duck for RAF bombers and Soviet submarines.

Captain Petersen proceeded with all the speed her engines would produce (12 knots) and kept the navigation lights on to avoid collision with friendly vessels. He decided to eschew the zig-zag course typically followed when operating in hostile waters, hoping the steadily falling snow would cover their escape.

His two escorts soon fell behind, unable to keep up. Below decks, the passengers suffered from seasickness, stifling heat, and poor ventilation.

Just after 9pm, about 12 miles off the Pomeranian coast, the Wilhelm Gustloff’s luck ran out. She was sighted by Soviet submarine S-13, commanded by Alexander Marinesko, a veteran captain whose boat had already been at sea 20 days without firing a shot. He had seen no targets important enough to expend his small supply of torpedoes.

Marinesko was not a committed communist, but he was a very capable submarine commander. Born in the Black Sea port of Odessa in 1913, he had left school early to take a job as a cabin boy on a freighter. A naturally talented mariner, he was recruited to the Soviet Navy and rose swiftly through the ranks.

In 1936, he transferred from the surface fleet to submarines, and got his own boat in 1937. For the next two years he managed to avoid Stalin’s purges. He ran a tight ship, but when the war came, he got little chance to show what he could do. Still, he must have impressed his superiors, because in 1944 he was transferred to the S-13, a much larger boat with improved capabilities.

For most of the war, the northern fleet of the Soviet Navy had been bottled up in its Baltic ports. Though possessing 218 submarines, these vessels were inferior to both German and Allied submarines, their crews poorly trained, and their torpedoes defective. Still, as German naval power collapsed in the Baltic, they were finally able to take to sea and attack the convoys bringing supplies in and taking refugees out of the shrinking German zone.

Submarine attack

On 11 January, the S-13 left Hangö in Finland to begin its first cruise in months. Nearly three weeks later, it was still looking for its first target. On the night of 30 January, while cruising on the surface, Marinesko found what he was looking for: a big target, the Wilhelm Gustloff, 25 miles off the coast and silhouetted against the shore.

He brought his boat into position and, at 1,000 yards, fired four torpedoes. One stuck in the tube but the other three hit home, 4.5 tons of steel and explosive imbedding themselves in the ship’s side.

The three hits seemed to lift the German liner out of the water. Then she began listing to port as water poured into her.

The blasts disabled the engines, extinguishing power and plunging the ship into darkness. The radio operator sent out a distress signal on emergency power, but because the frequency he was using was not a naval frequency, it was first picked up by the Hansa back at Gotenhafen. He continued sending out maydays for the next hour.

Meanwhile, passengers threw on coats and life-jackets and struggled to the boat deck, where the crew was desperately trying to work the frozen winches that lowered the lifeboats.

Other crewmen went below to try to close the watertight doors sealing off the damaged part of the hull. That was standard operating procedure in the event of a hull breach, but it did not save the ship – it merely trapped many of the off-duty crew in their quarters.

Passengers in the bowels of the ship were not much better off. Even if they could find their way along darkened passageways, they did not know the layout of the ship and therefore had no idea how to get out quickly.

Those lucky enough to get to the boat deck did not have it made. They found order had completely broken down, as no one was able to take charge of getting the lifeboats loaded and properly launched. Many of the crew were only interested in saving their own lives, fighting with passengers for a place in the lifeboats.

Women clutching infants in their arms begged anyone more likely to survive to take the child. But the most pitiful passengers were the pregnant women and the badly wounded soldiers; they had virtually no hope of escape. Occasional shots rang out in the frigid air, as armed officers fired warning shots trying to control the panic, while some armed passengers turned their guns on themselves, preferring to die by their own hand.

The best and the worst

Disaster can bring out the best or the worst in people. The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff was no different. Among the cases of heroism was that of an older woman who saved a teenage girl by pushing her into an alcove, putting her fur coat on her, then jumping overboard to take her chances in the water.

One burly seaman loaded a girl of the Women’s Auxiliary on to a lifeboat by shoving desperate men out of the way. Some men with pistols and families preferred to kill their loved ones quickly rather than have them die slowly in the icy waters. The sea temperature at that time of the year was typically 4ºC.

A Nazi official and his wife made a suicide pact, but after he killed her he could not bring himself to take his own life. A disgusted soldier nearby dispatched him with his own weapon.

In the water, survivors aboard lifeboats and life-rafts were not assured of safety. The rafts had only a net flooring, which left their occupants sitting in the water, and the few lifeboats that were launched attracted masses of desperate people in the water. As those people tried to clamber aboard, the occupants of one beat them off with fists and feet, until the sheer numbers capsized the boat, throwing everyone into the water to drown.

Shamefully, some of the ship’s officers, including Captain Petersen, were among the first into the lifeboats. Commander Zahn, after ordering ‘abandon ship’, remained on the bridge as long as possible, then jumped overboard and found a raft. When so many died that night, the question was asked afterwards, how did the ship’s master and its commander both manage to survive?

The sinking

The ship went down by the bow, even as she listed heavily to port. The severe listing made it impossible to lower lifeboats on the starboard side. The forward tilt sent people and objects crashing toward the bow.

Some found a seemingly safe spot and stayed there, hoping to be rescued before the ship went down. Others decided to take their chances by diving into the freezing waters. Still others had no choice: the tilting ship sent them skidding across the icy decks and over the side.

Those who stayed on board were as doomed as those who went into the water. One group numbering in the hundreds thought they had it made when they reached the glass-enclosed upper promenade deck. There, armed crewmen maintained order, assuring them they would be rescued if they remained calm.

It was all over in a matter of minutes. The ship rolled over on her side until her funnel was level with the water. Those passengers who had stood obediently on the promenade deck awaiting the promised rescue crashed through the windows and into the sea.

Some of the life-rafts that had been moored to the deck broke free and drifted away, providing a miraculous safe haven for those who could still clamber aboard. Seventy minutes after being torpedoed, the Wilhelm Gustloff slid beneath the Baltic to the sea bottom 150 feet down.

As she went under, her boilers exploded, briefly restarting the generators, causing the dying ship to light up eerily as she disappeared from sight.

On the surface, the sea was dotted with lifeboats and life-rafts, a few of which were occupied by one or two, while others were dangerously overcrowded. In the water, pitiable cries for help echoed for several minutes, slowly fading into silence. Survivors would state many years later that they could never forget those screams.

The heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and her escort were the first German ships on the scene. Already loaded down with more than 2,000 refugees and afraid of becoming a target herself, the Admiral Hipper steamed away without picking up a single survivor.

Her escort conducted rescue operations for an hour before also departing for fear of becoming submarine bait. During that time, however, she managed to save 550 people.

It would be five hours before other rescue vessels arrived. One of the last survivors to be picked up was the Wilhelm Gustloff’s radio operator, who had stayed at his post to the bitter end. For weeks afterward, hundreds of frozen bodies washed up on the nearby shore.

The death toll

The exact number lost that night has never been agreed on. Estimates range from as low as 6,500 to as high as 9,300. Nazi authorities at the time were not saying, if they even knew.

Whatever the total number on board when the ship left Gotenhafen, few more than 900 survived. German salvage efforts after the war eventually brought up the ship’s bronze bell, but the Baltic remained the watery grave of the ship and its thousands of passengers.

It was later claimed, without proof, that the Wilhelm Gustloff had been carrying, in addition to her human cargo, the famous ‘Amber Room’ of the Czar’s palace, looted from Leningrad by the Nazis earlier in the war. The priceless panels were last seen shortly before the Wilhelm Gustloff sailed and have not been seen since, adding an element of mystery to the tragedy.

Doenitz’s seaborne evacuation continued through 8 May, bringing away more than two million Germans, but leaving tens of thousands more either stranded or at the bottom of the Baltic. The General Steuben was sunk on 2 February, also by S-13, and the Goya on 16 April, each with the loss of thousands of lives. Operation Hannibal was the last large-scale operation of the Third Reich before it surrendered on 8 May 1945.

![german cruise ship sunk 1945 Gross Admiral Karl Doenitz [left] considered Operation Hannibal [below], the last major operation of the German Navy in the Second World War, a major success, despite disasters like the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff, General Steuben, and Goya. Indeed, the operation rescued more than two million people.](https://i0.wp.com/the-past.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/post-1_image8-6.jpg?w=1230&ssl=1)

None of the principals in the Wilhelm Gustloff tragedy came away looking good. Commander Zahn was called before a navy board of inquiry five days later. The board did not blame him, but they did not entirely clear him either, and his career was finished. Captain Petersen’s actions were roundly condemned, and he never commanded a ship again.

Captain Marinesko, who should have been a Hero of the Soviet Union, was not rewarded. Though he got his boat away safely, and subsequently sank the passenger liner General Steuben, carrying 4,000 passengers, making him the most successful Russian submarine commander in the Baltic, he was never credited by the high command with either sinking. He spent the next 15 years fighting for recognition, but only succeeded in making enemies and getting himself demoted and booted out of the service.

Whether the sinking was a legitimate act of war or a war crime was also debated, turning on whether she was a hospital ship or not. An investigation by a German institute that studies sea law decided the Wilhelm Gustloff was a legitimate military target because she was armed and carrying combatants (naval personnel).

The story of the Wilhelm Gustloff went largely untold in the West for many years, for several reasons. Germans had no reason to remember the horrific affair, in particular the series of official mistakes that contributed to it. In his memoirs, published in 1959, Admiral Doenitz estimated those lost in Operation Hannibal as only 1% of all brought away in the evacuation and counted it as one last, proud act of the German Navy. Nor did the Soviets celebrate either the sinking or their submarine commander.

As a maritime disaster, the Wilhelm Gustloff was worse than the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 (1,600 dead) and the Lusitania in 1915 (1,198 dead) combined. It has been compared to the sinking of the Lancastria on 17 June 1940 by German aircraft during the British evacuation of St Nazaire in France, but that killed ‘only’ about 4,000.

The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff seems especially tragic because it did not shorten the war by a single day, cost the lives of so many innocents, and no one involved covered himself in glory. In the end, it was all about payback. •

Latest from Military History

D-Day: Before the storm

Hitler’s Fortress Europe: Planning for defeat?

Dressing for battle: Arms and armour in the Roman Empire

The ghost of Genghis Khan

Looking death in the face: The battle for Beecher Island, September 1868

Orford Ness national nature reserve

War of words – ‘javelin’.

Back to the drawing board: HMS Captain

The Lionheart in winter: Richard I’s last campaign, 1194-1199

War On Film – Masters of the Air

Discover more from the past.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Terms of Use

War News | Military History | Military News

The sinking of the mv wilhelm gustloff is the single largest maritime disaster in history.

- War Articles

- World War 2

In January 1945 a German transport ship carrying thousands of civilian refugees from northern Europe was sunk in the Baltic Sea. She was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine and went down with an enormous amount of lives. To this day, the event remains the largest loss of life in a single ship sinking in history. This vessel is MV Wilhelm Gustloff.

Although at the time of sinking Wilhelm Gustloff was a transport ship, she was originally designed as a cruise ship.

The ship was designed and built for the Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy) organization. This state-operated organization was a Nazi effort to improve their public image and show off the benefits of Nazism. It offered workers affordable leisure opportunities like holidays, resorts, and cruises. Formed in 1933, it was actually a highly successful operation throughout the 1930s, becoming the largest tourism organization in the world . Its success continued until WWII began.

Wilhelm Gustloff was built to carry out cruises and other activities for people using the Strength Through Joy organization. It was laid down in August 1936 and completed on March 15, 1938. The vessel was the organization’s fleet flagship.

Originally she was to be named Adolf Hitler, but Hitler decided that it would be named after Wilhelm Gustloff , a high-ranking Nazi who had been recently assassinated. He made the decision after sitting next to Gustloff’s widow at the memorial service.

When complete she displaced over 25,000 tons and measured 208.5 m (684 ft 1 in) in length.

She started her first passenger voyage in late March 1938. On April 4 Wilhelm Gustloff received an SOS call from the small coal freighter Pegaway taking on water in a storm. The large vessel made her way to the Pegaway and lowered an oar-powered lifeboat to collect the stranded crew.

However, the rough seas battered the small, engineless lifeboat, a situation that also became an emergency. Wilhelm Gustloff lowered a second lifeboat – powered by an engine – which successfully collected both the crew of Pegaway and the crew from the first lifeboat.

Her official maiden voyage began on April 21, with the ship participating in a group cruise to the Madeira Islands. Shortly into the voyage the ship’s captain suddenly died of a heart attack. Captain Carl Lübbe was replaced by Friedrich Petersen.

Wilhelm Gustloff spent the next year on cruises all over Europe, transporting more than 80,000 passengers.

In September 1939 Wilhelm Gustloff’s career as a cruise ship ended, as she operated as a hospital ship until November 1940. She was then painted in a standard naval grey color and functioned as a barracks ship for U-boat crews in the port of Gdynia, Poland. She remained moored up here for the next four years.

Wilhelm Gustloff’s next, and final major action came in January 1945. The war was all but over for Germany, and it was now a case of trying to escape from the claws of the rapidly approaching Red Army. Operation Hannibal was a major German operation that evacuated around 1 million German civilians and soldiers across the Baltic Sea to the relative safety of Germany and its occupied territories.

Wilhelm Gustloff was loaded with civilians, soldiers, SS officials, and their families as well as scientists at Gotenhafen. She left the port on January 30.

The exact number of people on board the ship on this voyage is unknown, but the estimates are staggering. According to the ship’s own lists, she had over 6,000 people on board (she was designed to carry a maximum of less than 1,500). However, the urgency of the evacuation meant most vessels fled with far more passengers than were officially counted. One estimate states that 10,580 were on board, 9,000 of which were civilians.

After leaving the port the ship’s crew disagreed with the best course of action to ensure she arrived at her destination safely. Wilhelm Gustloff’s captain (the same man who took command on the Madeira Islands cruise) decided to travel in deep waters, and switch on the vessel’s lights to prevent collisions in the dark.

Soon into the journey the Soviet Stalinets-class submarine S-13 found Wilhelm Gustloff and tailed her for two hours. She fired four torpedoes at the overloaded ship at around 9 pm. One torpedo became lodged in its tube, but the other three launched successfully. All three struck Wilhelm Gustloff, causing instant mayhem inside. Remember, the ship had over four times more people on board than the Titanic, while being significantly smaller.

The ensuing panic among passengers trying to escape trapped many inside the doomed vessel. She quickly started listing to port, trapping even more.

The temperature that night was between -18 °C and -10 °C, with ice floes on the surface of the sea. The ice-cold conditions froze her lifeboats in place, stopping them from even being deployed.

Those who were able to escape the ship were met with the hypothermia-inducing temperatures of the ocean.

In all, around 9,600 people died in the disaster. This makes the destruction of Wilhelm Gustloff the largest loss of life in the sinking of any single ship.

Less than a week after the sinking, S-13 sank another ship, General von Steuben, killing a further 4,500 people.

- The Forgotten Maritime Tragedy That Was 6 Times Deadlier Than the <i>Titanic</i>

The Forgotten Maritime Tragedy That Was 6 Times Deadlier Than the Titanic

T he sinking of the Titanic may be the most infamous naval disaster in history, and the torpedoing of the Lusitania the most infamous in wartime. But with death counts of about 1,500 and 1,200 respectively, both are dwarfed by what befell the Wilhelm Gustloff , a German ocean liner that was taken down by a Soviet sub on Jan. 30, 1945, killing 9,343 people —most of them war refugees, about 5,000 of them children.

The victims of the worst maritime tragedy in history were not only Germans, but also Prussians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Poles, Estonians and Croatians. World War II was drawing to an end, and the Soviet army was advancing. Though it would be months before the final fall of the Nazi regime, it was clear the end was coming—and they were desperate to escape before things came to a head. As a result, 10,582 people were packed onto a cruise ship that was meant to accommodate only about 1,900. Though some on the ship were Nazis themselves, others had been the victims of Nazi aggression. When three torpedoes hit the ship, there weren’t nearly enough lifeboats, and many of the those that did exist were frozen to the deck. The majority of the passengers drowned.

Why is this event so little known? Novelist Ruta Sepetys can’t say for sure, but its obscurity made it exactly the kind of story she wanted to tell. The author has written a book for young readers called Salt to the Sea , out Tuesday, about four fictional young passengers on the Wilhelm Gustloff : an overeager Nazi manning the ship; a Lithuanian nurse doing her part but haunted by her past; a Polish girl concealing her nationality and the source of her pregnancy; and a Prussian carrying something Hitler wants.

Sepetys, an international bestseller thanks to her first novel Between Shades of Gray (which shares a character crossover with Salt to the Sea ) is drawn to “hidden histories.” She looked into the Wilhelm Gustloff after finding out that a cousin of hers would have been on board were it not for a last-minute decision to delay the travel, a choice that the cousin had feared would prove the wrong one. As it departed, “she was standing in the port crying, thinking that her life was over,” Sepetys says. The decision likely saved her life, in fact.

Intrigued, Sepetys immersed herself in research, particularly relying on the book Death in the Baltic but also on firsthand accounts from survivors she interviewed. “I hope this doesn’t sound too dramatic,” she says, “but what surprised me the most was that anyone survived.”

With the help of her publisher in Poland, she even tracked down two divers who had explored the wreck in the late ’60s under Soviet supervision. The Soviets were allegedly curious to see if the Germans had tried to use the refugee ship to evacuate treasure, too. “They did not share with me exactly what they brought up,” Sepetys says, “but yes, things were retrieved. And then there were instructions to detonate parts of the ship, because it was considered an obstruction in the water.”

So why do so few people know about the Wilhelm Gustloff ? Sepetys has a couple of theories. First, the Nazi regime actively tried to hide the facts. “They were amidst an evacuation and they didn’t want it to affect morale. They also were trying to hide the fact they were losing the war,” she says. “Some survivors reported that when they spoke of it, there was a knock on their door, and they were told, ‘Why are you telling stories about some ship? That didn’t happen.'”

In the aftermath of the war, she adds, Germans were hesitant to claim that they had been victims of any kind, so those who were free to discuss what had happened might have chosen not to.

This Is What Europe’s Last Major Refugee Crisis Looked Like

Another reason, she says, “could be that the submarine captain [who sank the ship], Alexander Marinesko, was dishonorably discharged shortly after,” apparently for disorderly conduct. At the time, Sepetys guesses, the Russians did not want to draw attention to him—though in later years monuments would be dedicated to his naval valor.

The Wilhelm Gustloff interested Sepetys as a story about refugees because her own Lithuanian father spent nine years in refugee camps before being settled in the U.S.—but she had no idea when she began her work that the story would prove relevant on a global scale, as the current influx of migrants in Europe draws comparisons to the migrations of the past. The author hopes getting to know her protagonists could help young readers and grown-ups alike empathize with people in situations far from their own. “Many families don’t have recent experience or connection to occupation or war,” she says. “But through story and characters, suddenly news and history become human.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Please enter at least 3 characters

Sinking the Wilhelm Gustloff

The sinking of a German liner resulted in the greatest loss of life on the high seas in history.

This article appears in: Late Winter 2014

By Chuck Lyons

Snow flurries swirled out of the darkness over the Baltic Sea. Chunks of ice floated on the water, and lookouts shivered at their posts. The German ship MV Wilhelm Gustloff plowed through the choppy water, her cabins, decks, saloons, and even her drained swimming pool jammed with refugees.

It was the night of January 30, 1945, and disaster awaited her.

On land, Soviet armies, enraged by earlier German atrocities, were moving into Poland and Prussia from the east, avenging themselves against the military personnel and civilians they met. Fleeing before them, refugees were streaming into the German-held Baltic ports, clogging the docks, and mingling with the wounded soldiers left by German ambulance trains. Horses that had pulled the cars that brought them and dogs that had tagged along were abandoned and wandered through the city. The roads and railways to the west were regularly being cut.

The only way out was by sea.

The Gustloff along with other liners, fishing boats, cargo ships, pleasure craft, and other vessels had been pressed into service to evacuate these refugees and military personnel, military technicians, and wounded soldiers in an operation that has been called the German Dunkirk.

But the Gustloff would not make it.

Not long after she began her journey west, she was spotted by the Russian submarine S-13 , which launched three torpedoes. All three hit the Gustloff , and within an hour she sank taking down with her as many as 9,500 people. It is the largest known loss of life of any sinking in maritime history, a loss of life more than three and a half times the total of those in the sinkings of the Titanic and the Lusitania combined.

The Gustloff in Operation Hannibal

From January to May 1945, as the Red Army advanced from the east, German refugees, military and civilian,were being evacuated through German-held ports on the Baltic Sea. Included among them were potential U-boat crews that had been training in the Bay of Danzig, wounded soldiers from the Eastern Front, Nazi officials, military families, and other civilians.

The evacuation, codenamed Operation Hannibal, was under the control of Admiral Karl Dönitz, who later succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of Nazi Germany. In that role, Dönitz would sign the Allied terms of unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945.

In January, however, he had taken charge of the evacuation and had requisitioned ships of all kinds, including 25 substantial cargo ships and 13 liners. One of those liners was the MV Wilhelm Gustloff . The ship had been built as the flagship of the German Labor Front and had been used by its Strength Through Joy organization to provide recreational and cultural activities for German functionaries and workers and to serve as a propaganda tool touting the glories of German power.

She was 684 feet long, 77.5 feet wide, weighed 25,484 gross tons, and could accommodate 1,465 passengers in 489 cabins. She was launched in May 1937 and was named after Wilhelm Gustloff, the head of the Nazi Party in Switzerland, who had been assassinated in 1936. Gustloff had been an ardent supporter of Hitler almost from the beginning of the latter’s rise to power and came to be considered a Nazi martyr after his assassination.

The Gustloff had been pressed into service as a transport ship during the Spanish Civil War, was later converted to a hospital ship, and in 1940 was converted again, this time to a barracks ship for U-boat trainees in Gdynia, Poland, on the Bay of Danzig.

By early 1941, the Soviet advance westward had freed the Navy’s submarine fleet, which had been bottled up in Leningrad and Kronstadt. The subs surged into the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland with orders to attack any shipping they encountered. The Germans, however, did not consider the submarines a menace, believing they were few and badly handled. A greater danger, the Germans believed at the time, came from British torpedo planes and bombers as well as from mines.

“A Safe, Comfortable Trip”

The Gustloff ’s original Operation Hannibal assignment was to carry to safety the 2nd Training Division of submarine recruits, men who had bunked on her during training. She was also to carry a number of women auxiliaries, some of whom had served in antiaircraft and artillery positions to free men for the front lines, and some wounded soldiers.

“We considered the Wilhelm Gustloff a safe, comfortable trip. It was for this reason that it became the first official evacuation ship for our girls,” Wilhelmina Reitsch, who was in command of the 10,000 female naval auxiliaries in the area, later said. “Because road and rail transport was so dangerous at the time, it was considered best to send these girls on the Gustloff . The auxiliaries were all between 17 and 25 years old. We carefully sifted through the auxiliaries and gave seaborne priority to those who had family or other responsibilities.”

As the ship awaited her orders to load passengers and leave Gdynia, there were daily bombing raids on shore, and the city’s electricity and water systems had broken down. The dock area was jammed with refugees and wounded soldiers trying to escape to the West and cluttered with horse-drawn covered wagons that had brought them to the docks.

“There must have been 60,000 people on the docks,” Walter Knust, the Gustloff’s second engineer, later said.

When the ship’s gangways were finally let down, refugees charged the ship trying to get aboard, fighting for a place on what they considered the only hope they had of finding safety. The ship was finally pulled a few yards away from the dock to stop the rush, and those with precious boarding passes were taken by ferry to the far side of the ship and up a guarded gangway.

Up to 10,582 Crew and Passengers on the Gustloff

About 1 pm on January 30, the Gustloff cast off. Aboard were 6,050 people: 173 crewmembers, 918 naval officers and men, 373 women’s naval auxiliaries, 162 wounded soldiers, and 4,424 refugees, including numerous women and children. It was windy and cold with hail bombarding the deck and the few passengers hardy enough to be outside. Bursts of snow mixed with the hail. Hunks of ice could be seen on the surface of the sea.

Lifejackets had been provided for all, but there were not enough lifeboats. Over the years, as the ship stood at the dock serving as a barracks, a number of the boats had been borrowed for other uses around the harbor. Lifeboats and rafts aboard the Gustloff could, if the need arose, accommodate only 5,060 people.

The ship was forced to stop almost immediately after casting off, however, when it was surrounded by a flotilla of small boats filled with refugees pleading to be picked up. Some women were holding up their children. Giving in to the pleading, the Gustloff ’s officers ordered boarding nets to be dropped from the ship, and refugees scrambled aboard. No one bothered to count them, but radio officer Rudi Lange later said, “I think I remember being told by one of the ship’s officers to send a signal that another 2,000 people had come aboard.”

That figure was probably an estimate at best, but if close it sent the Gustloff ’s complement to about 8,000 people. Other investigators, however, have claimed that number is actually quite low and estimated that those aboard totaled as many as 10,582 passengers and crew. The exact number will never be known.

The Gustloff then left Gdynia harbor accompanied by the passenger liner Hansa , which was also filled with civilians and military personnel, and with two torpedo boats to serve as a meager escort. The Hansa and one of the torpedo boats soon developed engine problems, however, and were forced to turn back.

A Legitimate Target of War

Over the years since the sinking, historians have argued about whether the Gustloff was a legitimate war target and whether her sinking should be classified as a war crime. Despite the wounded men on board, the Gustloff was not legally a hospital ship. She was armed with antiaircraft weapons and was also carrying a sizable number of military personnel. In addition, she was not marked as a hospital ship. She was a legitimate target.

Oddly, she also had two lead captains, one civilian and one military.

The military commander, Lt. Cmdr. Wilhelm Zahn, a submariner, argued that the ship should stay in deep water and make as much speed as possible either on a direct course or, preferably, zigzagging. He was overruled by the senior civilian captain, Friedrich Petersen, who argued that the ship could not maintain her top speed for long and was too large to hold a zigzag course. In addition, the ship was informed by radio of a number of German minesweepers in the area, and Zahn recommended turning on the ship’s green and red navigation lights to avoid a collision in the dark. German intelligence had already informed the Gustloff that there were no known Soviet submarines or surface ships in the area.

That report of no submarine activity was wrong, and the running lights would make the Wilhelm Gustloff easy to spot in the dark.

Meanwhile, the crowded conditions below decks had overwhelmed the ship’s ventilation system, making it oppressively hot. To make themselves more comfortable, people began removing their lifejackets.

As the ship sailed 15 to 20 miles off Leba, Poland, the Soviet submarine S-13 was prowling the area, and its commander, Captain Alexander Marinesko, was preparing to slip into the Bay of Danzig itself in hopes of finding targets.

“I decided,” he later said, “that I would bring the war to them.”

As the submarine headed for the bay, however, Marinesko noticed the running lights of the Gustloff and resolved to attack her on the surface, slipping close on the shore [port] side of the ship to fire torpedoes with greater accuracy. Snow flurries and clouds obscured the moon and helped hide the silhouette of the submarine against the darkness of the shore.

“They would not expect an attack from that direction,” Marinesko remembered. “Their watch would be concentrating on looking out to sea.”

The S-13 worked itself around the ship and to fewer than 1,000 meters from the Gustloff . The torpedoes were set to run three meters below the surface. Marinesko fired.

The Gustloff Hit

Before leaving on patrol, S-13 ’s Petty Officer Andrei Pikhur had painted slogans on the boat’s torpedoes. These torpedoes ran silently toward the Gustloff with the first, which had been labeled “For Motherland,” striking the Gustloff near the bow. The second torpedo, marked “For Soviet people,” hit just ahead of amidships, and the third torpedo, “For Leningrad,” struck the engine room below the ship’s funnel, cutting off electrical power. A fourth torpedo, “For Stalin,” hung up in its tube.

The Gustloff lurched to starboard and then settled to port and began listing. Her nose was down. At first, some of the officers thought the ship had hit a mine, but Zahn, himself a submariner, realized the ship had been hit by three torpedoes. The engines had been knocked out, and the ship’s telephone and public address systems were down. Those lucky enough to have cabins were able to quickly get out on the slanting deck, but below people were screaming and running around while alarm bells and sirens bellowed. Water poured into the ship’s corridors, and panicked people waded through first knee-deep and then thigh-deep streams. Anyone who fell was trampled. The wounded and the many pregnant women aboard, lacking mobility, were trapped below.

Those who made it to the boat deck fought to get on the few lifeboats. Others jumped into the water. Many of the davits holding the lifeboats in place were coated with ice, and the inexperienced crew struggled to knock them free and launch the boats. Others boats capsized as they hit the water, dumping those aboard into the freezing Baltic, or snarled when being lowered, spilling their passengers.

Sinking in the Baltic Sea

Meanwhile, the ship’s list to port continued to grow, and people began to slip and slide across the wet and icy deck into the water. Ironically, the PA system had been quickly repaired, and messages meant to reassure the panicked passengers continued to sound.

The main radio system was not operating, and water was pouring into the engine room. An emergency transmitter, which had a range of only 2,000 meters, was pressed into service, but it could not reach the naval headquarters. Its messages were picked up by the escorting torpedo boat, which then relayed them on its more powerful transmitter. But it transmitted the messages for help on a frequency reserved for warships. Valuable time was thus lost in notifying potential rescue ships.

Finally, the great ship’s bulkheads and watertight doors gave way under the pressure of the water pouring into her, and she turned over on her port side, spilling those people still on the lower promenade deck against the windows, then out into the Baltic as the glass gave way. Others were caught and drowned.

On the bridge, 45 minutes after the torpedoing and with the ship listing 25 degrees, Zahn was overseeing the destruction of the ship’s papers when steward Max Bonnet, wearing his white jacket, politely appeared with a tray and glasses offering the officers on the bridge “a final cognac.”

The bridge officers drank their cognacs and returned to work. Shortly after that, the ship began her final slide to the bottom. Her boiler exploded, somehow reactivating her generators and lights as she slipped beneath the waves.

“Suddenly it seemed every light in the ship had come on,” said passenger Ebbi von Aydell, who had been lucky enough to get aboard one of the lifeboats. “The whole ship was blazing with lights, and the sirens sounded out over the sea.”

Another witness, Walter Knust’s wife, Paula, also watched the Gustloff ’s last moments from a lifeboat.

“I could clearly see the people still on board clinging to the rails. Even as she went under they were still hanging on and screaming. All around us were people swimming or just floating in the sea. I can still see their hands grasping at the sides of our boat,” she remembered.

7,000 to 9,400 Deaths

In less than an hour, the Gustloff was gone, sunk in 144 feet of water. The Gustloff ’s escort boat and other ships in the area, including the German cruiser Admiral Hipper , converged on the area and began bringing aboard as many of the Gustloff ’s survivors as they could.

In all, 1,063 people were rescued, including both of the ship’s captains, but some of those rescued died later. In the panic that had followed the torpedo attack, a number of people were trampled and killed, and others were killed outright by the three torpedo blasts. The majority died, however, in the frigid Baltic water. The air temperature that night was no higher than 14 degrees Fahrenheit, and ice floes were forming on the surface of the sea. The actual number killed, like the actual number aboard the ship, is unknown but estimates range from about 7,000 to as many as 9,400 people.

Depth charges were also fired, which may have killed some of the people floating and swimming in the area. The sudden movements of some of the rescue ships trying to evade the submarine may have killed others.

The ships took many of those rescued west to Sassmitz on the German island of Rugen off the Pomeranian coast. There they were met by the Danish hospital ship Crown Prince Olav. Others drifted for hours before being picked up by other vessels and taken to shore. A group of seven survivors, including one of the few naval auxiliary women to survive, was taken to Gdynia. Twenty-four hours after they had disembarked, these passengers were back in the same place they had left and were taken to the military hospital there. Of the seven only two were well enough to walk ashore under their own power.

The final rescue came at dawn when a Navy dispatch boat was edging through the ice. She had all but given up on finding any additional survivors when she came on a lifeboat with several people huddled aboard. Chief Petty Officer Werner Fisch jumped into the boat and it appeared that all the people on it were dead, apparently frozen to death. Looking further, however, he found buried in the mass of dead a baby who was still alive. Fisch took the child back to the dispatch boat and later adopted it.

S-13 ‘s “Red Banner”

After the sinking, Marinesko continued his patrol and in February sank another liner, the 14,660-ton Steuben , that was also being used in the evacuation. The Steuben went down with almost 4,000 wounded German soldiers, civilians, Army and Navy personnel, and crewmen aboard.

For its exploits in the Baltic, S-13 was made a “Red Banner” boat, and every member of the crew was granted the Order of the Great Patriotic War.

As the war wound down, Marinesko wrote a book, An Analysis of Torpedo Attacks by the S-13 , which was never published. The book did anger many of his superiors with its criticism of Soviet tactics and equipment. This, as well as Marinesko’s outspoken views and less than circumspect behavior, led to his eventual dismissal from the service. Out of the Soviet Navy, he continued to get in trouble with the authorities and ended up being sentenced to a three-year term at a Siberian labor camp.

Zahn was called before a German naval board to answer for what had happened, but as the Third Reich collapsed no decision was rendered and no blame was ever placed for the ship’s overcrowding or for the running lights that had made her so conspicuous.

Zahn spent the remainder of his life as a salesman, and civilian captain Petersen never went to sea again.

For weeks after January 20, 1945, frozen bodies washed up on the Baltic coasts.

Back to the issue this appears in

Join The Conversation

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share This Article

- via= " class="share-btn twitter">

Related Articles

Bataan and Corregidor: Valor Without Hope

The Shinano Carrier: How Allied Forces Sunk Such a Secret

The Bloody Triangle along WWII’s Eastern Front

European Theater

Defending the Skies Above the Reich

From around the network.

Military History

Opening Moves on the Rio Grande: The Relief of Fort Texas

Warsaw Uprising: The Story of Bogdan Mieczkowski

Portugal during WW2: Covering the Azores Gap

Book Reviews

James A. Villanueva’s ‘Awaiting MacArthur’s Return’

Sinking of MV Wilhelm Gustloff- The Deadliest Maritime Disaster

Introducing a topic about wartime maritime disaster , invariably leads one to broach the topic of the ill-fated Wilhelm Gustloff, termed as the deadliest maritime disaster in the maritime history.

A construction that was envisioned as the ultimate cruise vessel, turned into a hospital ship before finally being transformed into a navy personnel carrier, MV Wilhelm Gustloff was a German ship which was sank by a soviet submarine. More than 1500 people died in this worst peacetime maritime disaster.

About MV Wilhelm Gustloff

The vessel’s christened name was the Nazi way of immortalising one of their party members, a commander of the National Socialist Party in Switzerland. The vessel was originally designed to be the best cruise ship, offering both luxury and a distinct lack of societal class distinction.

The construction for the ship was started under Hitler’s command in the late 1930s, though by the time the construction was complete and the vessel was put to use, the Second World War had broken out. Gustloff was resultantly converted into a hospital ship to carry injured naval men and civilian persons – quite a downturn from the elaborate envisioning for its life and times.

Life and Times of the Hospital Ship

The Gustloff started its life as a hospital ship in the year 1939; two years post its launch as a cruising vessel. However even as a hospital vessel, she was marginally utilised (1939-1940) before she was yet again re-furbished to serve as a carrier to house the crew of the German submersibles.

Her position as a carrier vessel for crewmen was in the Gdynian – then known as Gotenhafen – port, in Poland, where she was moored till she was re-commissioned in the historic Operation Hannibal. While functioning as a housing vessel, the Gustloff provided accommodation for almost 1,000 naval personnel.

Operation Hannibal

In the year 1945, the Second World War had come to a head. The Allied powers were unanimously winning, while all German strategies were falling apart right in front of their eyes. The Operation Hannibal was the last-attempt by the German forces and commanders to salvage their wartime losses and create a survival story of their own.

The operation involved providing a safe place for all German troops and civilians trapped in the Soviet Union’s marauding path in the Nazi-occupied Poland, through the marine route. At the time of the Gustloff sinking , there were estimated to be over 10,000 people housed within it.

Along with the Wilhelm Gustloff , there were other vessels that were mobilised to carry out similar operations. Gustloff itself was in the command of four captains, three naval captains and a civilian skipper, who were in-charge of the people aboard the vessel.

Ship Sinking Incident

The Gustloff sinking happened in the Baltic Sea, when the Soviet submersible S-13 under the skippering of Capt. Marinesko, fired missiles and torpedoed the German vessel. In the many decades, since the incident occurred, there have been many who have raised the question of whether the incident could have been averted.

The most-experienced of the four skippers in the hospital ship decided to steer the vessel in the clear sea instead of steering it near the sea-coasts. Both routes had dangers – the former had the threat of Soviet submersibles while the latter had the threat of underwater explosives. However because of the insistence of the skipper, the former route was chosen and the lights of the German vessel were lighted to help any other German vessels in the vicinity to take notice.

Contrarily, the lights also attracted the attention of the submersible which led to the vessel being attacked and a huge chain of events being unfolded. Out of all the people aboard the Gustloff at the time of the ship sinking , only a handful – around 1,200 – could be saved. The rest sank into the freezing depths of the Baltic Sea, never to be heard of again.

Implications

The maritime disaster of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff is one that will haunt the German nationals forever. It is a repercussion of the over-confident Nazi mentality, a result of lofty aspirations and the lack of ability to achieve these aspirations. The people who lost their lives may not be martyrs in the literal sense of the word but they did sacrifice their lives, for their country and countrymen.

[stextbox id=”info” caption=”Read More About”] Halifax Explosion Selandia INS Khukri Bimini Road Mystery HMVS Cerberus [/stextbox]

You may also like to read – Mysterious & Horrific Maritime Disaster: The Story of the Kursk Disaster

References & Image Credits

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

One Comment

Gunther Grass wrote an interesting book on the subject “Crabwalk”.

I also saw a documentary on the history channel about a floating concentration camp in which the Germans were hoping it would be sunk by the RAF which it was and thousands perished by the sinking and also when swimming back to shore German soldiers shot at and killed hundreds of the escaping survivors.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Marine Insight Daily Newsletter

" * " indicates required fields

Marine Engineering

Marine Engine Air Compressor Marine Boiler Oily Water Separator Marine Electrical Ship Generator Ship Stabilizer

Nautical Science

Mooring Bridge Watchkeeping Ship Manoeuvring Nautical Charts Anchoring Nautical Equipment Shipboard Guidelines

Explore

Free Maritime eBooks Premium Maritime eBooks Marine Safety Financial Planning Marine Careers Maritime Law Ship Dry Dock

Shipping News Maritime Reports Videos Maritime Piracy Offshore Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) MARPOL

- Federal Court

- Constitution - 2013

- Boulton Lecture

- From the Federal Secretary

- Melbourne Log

- Melbourne Notices

- Melbourne Minutes

- The Voicepipe

- Queensland Notices

- The Megaphone

- Sydney Notices

- The Porthole

- South Australia Notices

- Points West

News & Articles

- News - Australia / NZ

- News - International

- Stories from the past

- Archived Articles

- Newsletters

- The Wilhelm Gustloff (1945): The deadliest shipwreck in history

History’s deadliest shipwreck occurred in 1945, when some 9,000 people perished after a German vessel, the Wilhelm Gustloff, was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine in the Baltic Sea.

On January 30, 1945, some 9,000 people perished aboard this German ocean liner after it was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine and sank in the frigid waters of the Baltic Sea. The Gustloff, named for a Nazi leader in Switzerland assassinated in 1936, was constructed as a cruise ship for the Nazis’ “Kraft durch Freude” (“Strength through Joy”) program, which provided recreational activities for working-class Germans. Adolf Hitler launched the 684-foot-long, 25,000-ton vessel in 1937. However, its cruising career was brief; after World War II began in 1939, the German military converted the Gustloff into a hospital then later used it as a U-boat training school.

In January 1945, as the Soviet army advanced on East Prussia, the Nazis launched Operation Hannibal, a mass naval evacuation of German military personnel and civilians from the region. On January 30, as part of Operation Hannibal, the Gustloff left the East Prussian port of Gotenhafen (which today is the Polish city of Gdynia) bound for Kiel, Germany. The Soviet submarine S-13 soon spotted the Gustloff and blasted it with three torpedoes. The German liner sank within 90 minutes, about 12 nautical miles off Stolpe Bank near present-day Poland. Historians now estimate that only about 1,000 of the approximately 10,000 people aboard the Gustloff survived, making it the deadliest maritime disaster in history.

In the aftermath, the world learned little about the disaster for a variety of reasons. The Nazi regime kept news of the sinking out of the headlines and censored survivors, and some survivors kept quiet because they felt guilty about their German heritage and the atrocities Nazi Germany had inflicted on millions of people.

Source: history.com

- You are here:

- Follow via Facebook

The Deadliest Disaster at Sea Killed Thousands, Yet Its Story Is Little-Known. Why?

In the final months of World War II, 75 years ago, German citizens and soldiers fleeing the Soviet army died when the “Wilhelm Gustloff” sank

Francine Uenuma

History Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/d3/ead39ecb-3af2-4388-b51d-65b97dcd764e/c45e9c.jpg)

By the time the Soviet Union advanced on Germany’s eastern front in January of 1945, it was clear the advantage in World War II was with the Allies. The fall of the Third Reich was by this point inevitable; Berlin would succumb within months. Among the German populace, stories of rape and murder by vengeful Soviet forces inspired dread; the specter of relentless punishment pushed many living in the Red Army’s path to abandon their homes and make a bid for safety.

The province of East Prussia , soon to be partitioned between the Soviet Union and Poland, bore witness to what the Germans called Operation Hannibal, a massive evacuation effort to ferry civilians, soldiers and equipment back to safety via the Baltic Sea. German civilians seeking an escape from the advancing Soviets converged on the port city of Gotenhafen (now Gdynia, Poland ), where the former luxury ocean liner Wilhelm Gustloff was docked. The new arrivals overwhelmed the city, but there was no turning them back. If they could get to the dock and if they could get on board, the Gustloff offered them a voyage away from besieged East Prussia.

“They said to have a ticket to the Gustloff is half of your salvation,” ship passenger Heinz Schön recalled in an episode of the early 2000s Discovery Channel series “ Unsolved History .” “It was Noah’s Ark.”

The problem, however, was that the Soviet navy lay in wait for any transports that crossed their path and sank the Gustloff 75 years ago this week in what is likely the greatest maritime disaster in history. The death toll from its sinking numbered in the thousands, some put it as high as 9,000 , far eclipsing those of the Titanic and Lusitania combined.

Most of the Gustloff ’s estimated 10,000 passengers—which included U-boat trainees and members of the Women’s Naval Auxiliary—would die just hours after they boarded on January 30, 1945. The stories of the survivors and the memory of the many dead were largely lost in the fog of the closing war, amid pervasive devastation and in a climate where the victors would be little inclined to feel sympathy with a populace considered Nazis—or at the very least, Nazis by association.

Before the war, the 25,000-ton Wilhelm Gustloff had been used “to give vacationing Nazis ocean-going luxury,” the Associated Press noted shortly after its 1937 christening, part of the “Strength Through Joy” movement meant to reward loyal workers. The ship was named in honor of a Nazi leader in Switzerland who had been assassinated by a Jewish medical student the year before; Adolf Hitler had told mourners at Gustloff’s funeral that he would be in “the ranks of our nation’s immortal martyrs.”

The realities of war meant that instead of a vacationing vessel the Gustloff was soon used as a barracks; it had not been maintained in seaworthy condition for years before it was hastily repurposed for mass evacuation. Despite having earlier been prohibited from fleeing, German citizens understood by the end of January that no other choice existed. The Soviet advance south of them had cut off land routes; their best chance at escape was on the Baltic Sea.

Initially German officials issued and checked for tickets, but in the chaos and panic, the cold, exhausted, hungry and increasingly desperate pressed on board the ship and crammed into any available space. Without a reliable passenger manifest, the exact number of people onboard during the sinking will never be known, but what is beyond doubt is that when this vessel—built for less than 2,000 people—pushed off at midday on the 30th of January, it was many times over its intended capacity.

Early on, the ship’s senior officers faced a series of undesirable trade-offs. Float through the mine-laden shallower waters, or the submarine-infested deeper waters? Snow, sleet and wind conspired to challenge the crew and sicken the already beleaguered passengers. Captain Paul Vollrath, who served as senior second officer, later wrote in his account in Sea Breezes magazine that adequate escort ships were simply not available “in spite of a submarine warning having been circulated and being imminent in the very area we were to pass through.” After dark, to Vollrath’s dismay, the ship’s navigation lights were turned on—increasing visibility but making the massive ship a beacon for lurking enemy submarines.