Robert Heinlein

- View history

Robert A. Heinlein was a famous science fiction writer on Earth in the 20th century . The Puppet Masters was one of his works.

The 1950s magazine Galaxy featured stories by Heinlein, as well as Ray Bradbury and Theodore Sturgeon . Herbert Rossoff believed that if he joined the magazine it would "complete" the lineup. ( DS9 : " Far Beyond the Stars ")

Appendices [ ]

Background information [ ].

In 1966 , Robert Heinlein was invited, by Gene Roddenberry , to write for Star Trek: The Original Series . Heinlein turned down the offer, though. ( These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One , Chapter 1: "The Creator") At the time, Heinlein was considered one of the "Big Three" of science fiction authors, alongside Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, the latter two known as staunch supporters of Roddenberry's creation. Invited by Asimov to tag along, Heinlein did attend the 1976 "Bi-Centennial-10 Star Trek Convention " at the Hilton Hotel in New York City. [1]

A photograph of a raktajino bottle seen in The Art of Star Trek shows a label identifying the beverage as imported by Harcourt Mudd and bearing the slogan "Made from The Green Hills of Earth ", the title of one of Heinlein's works.

The tribbles are similar to the "Martian Flat Cats" in Heinlein's novel The Rolling Stones , which made the producers of " The Trouble with Tribbles " nervous about a possible lawsuit. Finally, they phoned the author, who was satisfied with a simple "mea culpa" from Gene Roddenberry. ( Inside Star Trek: The Real Story , pp. 333-334)

Heinlein invented the verb "grok" (roughly meaning: to completely and totally understand), used in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land . " I grok Spock " was a popular t-shirt and bumper sticker slogan used by Trekkies in the 1970s.

Heinlein was a good friend of Star Trek author G. Harry Stine , and Heinlein's novel Have Space Suit—Will Travel is dedicated to Stine and his wife.

According to the Star Trek Encyclopedia (4th ed., vol. 1, p. 332), the birth and death years of Robert Heinlein were 1907 and 1988 , respectively. The authors of this reference work noted that Heinlein was sometimes known as the "Dean of science fiction" because of his role in developing the genre into a sophiscated mode of literary expression. In a note to the entry about this author, it is stated, " Many students of science fiction have regarded Heinlein's works as being a significant influence on Gene Roddenberry 's development of the original Star Trek television series. "

External links [ ]

- Robert Heinlein at Wikipedia

- Robert Heinlein at the Internet Movie Database

- Robert Heinlein at Memory Beta , the wiki for licensed Star Trek works

- Robert Heinlein at SF-Encyclopedia.com

- 2 Star Trek: The Next Generation

- 3 USS Enterprise (NCC-1701-G)

Memory Beta, non-canon Star Trek Wiki

A friendly reminder regarding spoilers ! At present the expanded Trek universe is in a period of major upheaval with the finale of Picard and the continuations of Discovery , Lower Decks , Prodigy and Strange New Worlds , the advent of new eras in Star Trek Online gaming , as well as other post-56th Anniversary publications such as the new ongoing IDW comic . Therefore, please be courteous to other users who may not be aware of current developments by using the {{ spoiler }}, {{ spoilers }} or {{ majorspoiler }} tags when adding new information from sources less than six months old . Also, please do not include details in the summary bar when editing pages and do not anticipate making additions relating to sources not yet in release. ' Thank You

- 1907 births

- 1988 deaths

- Humans (20th century)

Robert A. Heinlein

- View history

Heinlein wrote for the science fiction publication Galaxy Science Fiction in the 1950s and was the author of The Puppet Masters . ( DS9 episode : " Far Beyond the Stars ")

The Vulcan S'task unknowingly surmised Heinlein's Law in his publication, A Study of Socioeconomic Influences on Vulcan Space Exploration , and Heinlein's concept of a threshold number in Statement of Intention of Flight . ( TOS - Rihannsu novel : The Romulan Way )

Heinlein is the namesake of the 22nd century Earth Starfleet starship USS Heinlein , and the 23rd century Federation Starfleet vessel USS Robert A. Heinlein .

External links [ ]

- Robert A. Heinlein article at Memory Alpha , the wiki for canon Star Trek .

- Robert A. Heinlein article at Wikipedia , the free encyclopedia.

- 1 Ferengi Rules of Acquisition

- 2 Odyssey class

- 3 USS Enterprise (NCC-1701-F)

Locus Online

The Magazine of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Field

The Joke Is on Us: The Two Careers of Robert A. Heinlein

by Gary Westfahl

To convey the full extent of his pervasive effects on science fiction, one can consider the three, commonly accepted periods of Heinlein’s career, as first defined in Alexei Panshin’s Heinlein in Dimension (1968), a pioneering and seminal study despite its flaws. From 1939 to 1942, Heinlein wrote exclusively for the science fiction magazines, with John W. Campbell, Jr.’s Astounding Science-Fiction as his venue of choice (since it paid the highest rates). From 1945 to 1959, while still contributing to science fiction magazines, Heinlein focused most of his energies on breaking into more lucrative markets, including a famous series of juvenile novels for Scribner’s, stories written for “slick” magazines like The Saturday Evening Post , and film and television projects. And from 1961 until his death in 1988, Heinlein specialized in writing novels that were increasingly long-winded, idiosyncratic, and highly opinionated.

Each of these three bodies of work has had its own sort of influence. The remarkably variegated and creative stories and novels from his first period remain the favorites of critics and connoisseurs, and science fiction writers who are serious about internalizing and maintaining the genre’s finest traditions will carefully study, and seek to emulate, the most memorable items from this era. Thus, many writers have produced their own variations on the intricately convoluted time-travel story, as so artfully rendered in “By His Bootstraps” (1941), or have provocatively explored the notion that reality is not as it seems, as exemplified by stories like “They” (1941) and “The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag” (1942). The novels of his middle period, especially the juveniles, have inspired almost all of the science fiction writers who produce space adventures, both the generation who grew up reading and admiring those books and later authors who absorbed Heinlein tropes from second-hand sources ranging from Star Trek to Lois McMaster Bujold. And the cracker-barrel philosophy foregrounded in the later novels was most admired by writers and readers of a libertarian bent, who virtually deified Heinlein as their patron saint and created entire subgenres of “military science fiction” and “libertarian science fiction” that seem especially indebted to those works.

The problem, as I see it, is that these three periods, even though they can be clearly identified by different markets and certain obvious similarities, do not accurately define the career of Robert A. Heinlein and have led to egregious misinterpretations of several key works. Thus, I wish to argue instead that there were, in fact, only two periods in Heinlein’s career: from 1939 to 1957, Heinlein wrote science fiction, and from 1958 until his death in 1988, Heinlein wrote satires of science fiction. Or, if that language seems too strong, say that from 1939 to 1957, Heinlein took his science fiction very seriously, and after that, he no longer took his science fiction seriously.

The evidence for this crucial shift in Heinlein’s development is clearest in his later juveniles. As critics repeatedly note, the first eleven novels, while officially unrelated, collectively present a future history of humanity, beginning with stories about the exploration and colonization of nearby worlds in the Solar System and moving further into the future to depict humans making regular trips to distant stars, encountering intelligent aliens, and establishing communities throughout the galaxy. As the title of his eleventh juvenile indicates, Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) effectively functioned as the culmination of this grand narrative, describing a mature interstellar civilization of innumerable inhabited worlds with a few lingering issues to resolve (most prominently, the curious reappearance of slavery). After completing this novel, Heinlein might have logically felt that he had taken the saga of humanity’s future about as far as it could go without venturing in discomfiting territory, like the emergence of a genuinely superhuman race or the tragedy of our species’ inevitable decline.

As to why this sea change in Heinlein’s career occurred in the year 1957, there is one obvious event to consider: the October, 1957 launch of Sputnik, humanity’s first venture into outer space, which a man like Heinlein may have reacted to in two ways. First, there might be a sense of vindication: although Heinlein’s stories and novels for adults had involved a variety of topics and themes, each and every one of his juveniles had focused on space travel, suggesting an intent to persuade Americans that, more than anything else, humanity’s future depended upon vigorous expansion into space. Sputnik clearly indicated that Heinlein and other science fiction writers had succeeded in achieving this goal: humans were finally venturing into the cosmos, and everyone in the science fiction community had long been confident that, once space exploration had started, further progress to the Moon, Mars, and beyond was virtually inevitable. Thus, Heinlein might have thought, with its serious purpose accomplished, science fiction could now relax and be dryly humorous instead of earnestly didactic. A second reaction might be alarm, inasmuch as it was the communist Soviet Union, not the democratic United States, that had taken the lead in the space race, creating the strong possibility that they would soon dominate space, and thus dominate the Earth as well (precisely the argument Heinlein had made in Destination Moon ). As his nonfictional response to this ominous threat, Heinlein had briefly attempted to launch a political movement with his 1958 advertisement-essay “Who Are the Heirs of Patrick Henry?,” shrilly arguing that a planned nuclear test ban treaty would amount to surrendering America to the insidious communists. Arguably as his fictional response, then, Heinlein might have turned to the natural tool of the distressed writer, satire; thus, among other things, Starship Troopers can be read as Heinlein’s take on the Cold War, with loathsome, insect-like aliens standing in for the Russians. Later, when Heinlein was reassured by America’s space initiatives and realized that a test ban treaty was not going to mean the end of the world, the new satirical approach he had adopted would gradually lose its hard edge and become more playful.

I do not wish to suggest that Heinlein’s later novels were entirely insincere; to a certain extent, Heinlein always meant exactly what he said. However, when one decides to be a little bit outrageous, to convey deeply felt opinions in a slightly overstated manner, in order to amuse readers – the plan I detect in Starship Troopers and Stranger in a Strange Land – and when one then finds that there is an enthusiastic audience for these works, the natural response is to be even more outrageous, to state one’s views in an even more exaggerated fashion, to see how far one can go in this direction. And if those further efforts are still getting rave reviews, one eventually evolves into a parody of oneself, offering a self-portrait so distorted and ridiculous that it should provoke laughter, its underlying purpose, but may instead perversely continue to attract worshipful admiration. One observes this process in the film Network (1976), where newscaster Howard Beale, upon hearing his show will be cancelled, goes a little bit crazy on the air, sees his ratings skyrocket, and in response naturally becomes crazier and crazier while garnering acclaim as “the Mad Prophet of the Airwaves.” Indeed, reading some of the wilder rants in his later novels, someone unfamiliar with his earlier triumphs might dub Heinlein “the mad prophet of science fiction.”

Some will protest that the usually-candid Heinlein never stated or hinted, in interviews and speeches during the final decades of his life, that any of his novels and the viewpoints therein were less than entirely serious – but that is only what we would expect, considering the one characteristic of Heinlein that everyone can agree was a constant throughout his entire career: an overriding concern for the bottom line. If Heinlein was receiving enthusiastic fan letters about the life-transforming effects of the philosophies in his recent novels, and if healthy sales figures indicated that such reactions were commonplace, Heinlein was far too wise to disrupt the flow of income into his bank account by suggesting that, actually, his tongue had been firmly in his cheek. In a strange fashion, one might say, Heinlein had evolved into a latter-day equivalent of his old colleague from the Astounding Science-Fiction of the 1940s, L. Ron Hubbard, who became fabulously wealthy by launching and leading a new religion that, many whispered, was motivated more by greed than by genuine revelation. While the cult of Heinlein has never adopted the formal trappings of a religion, many of its followers now seem just as devoted to its doctrines as any Scientologist – and dare one suggest that they might also be just as deluded about the sincerity of its founder?

The new context I am proposing for Heinlein’s fiction opens the door to provocative reconsiderations of his later novels. In the first place, we can soundly reject the indignation of Alexei Panshin, who lambasted Stranger in a Strange Land and its successors for their indefensible views and emphasis on self-expression at the expense of storytelling. But Panshin failed to recognize that Heinlein was in fact gradually developing what would become his most entertaining and memorable character: “Robert A. Heinlein,” the garrulous sagebrush savant who would sometimes speak directly to readers and sometime employ mouthpieces like Harshaw and Long. Angrily denouncing this fictional character is as ridiculous as angrily denouncing Iago. In addition, a common criticism of Paul Verhoeven’s film Starship Troopers (1997) is that he imposed a layer of irony upon Heinlein’s straightforward story; but allow me to suggest that he was crudely bringing to the surface the irony that was already subtly present in the novel. I would further suggest another interpretation of Farnham’s Freehold (1964), usually regarded as the racist skeleton in Heinlein’s closet, depicting the latest version of the Heinlein Hero valiantly struggling against a corrupt and repressive African-American dictatorship in a future America. But carefully examined, Hugh Farnham actually emerges as a vindictive parody of the Heinlein hero, a stupid, self-deluded incompetent who is unable to accomplish anything, and the society he awakens in represents precisely the sort of absurd paranoid fears that this sort of idiot would develop. In the end, Farnham does the only thing that such a pathetic person can do: build a wall around his house to protect himself from a world he cannot cope with. By the time we get to The Number of the Beast , wherein Heinlein’s protagonists venture into some famous fictional realms and eventually get some sound advice from Glinda, the good witch from L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), I think it couldn’t be clearer that Heinlein is by association labeling his later creations as diverting fantasies, not somber extrapolations. And this new perspective on Heinlein provides a solution to one mystery in To Sail Beyond the Sunset , wherein Heinlein argues, among other things, that it’s all right for a man to sleep with his daughter, but hey, if he ever happens to smoke a joint, he should be lynched on the spot. How on Earth, I once wondered, could a sane person actually hold such views? The only reasonable answer is that a canny old author was merely taking his satirical Heinlein act one step further in an effort to see if, finally, someone would figure out what he was really doing.

Properly understanding the later Heinlein novels, finally, we can account for the peculiar failures of the literature they engendered. Emulating the Heinlein of the 1940s, who always strived to be as boldly imaginative as possible to impress Campbell, science fiction writers have impressively stretched the boundaries of the genre; emulating the Heinlein of the early juveniles, writers have crafted admirably entertaining space operas with wise-cracking, capable protagonists who take care of business throughout the cosmos. These are the stories that attract a wide readership, laudatory reviews, and occasional awards. But writers who have emulated the Heinlein of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s have produced various works of “military” or “libertarian” science fiction that are mostly devoted to monotonous, mindless adventures interspersed with heavy doses of didactic ideology. And this dire body of literature is generally and thankfully ignored, except by fanatics who share their authors’ views (and curious scholars investigating current trends in science fiction – yes, I have read some of these works, and I do know what I am talking about). And why are these stories so unsuccessful? Because they are jokes without punch lines; they are stone-faced, solemn redactions of what Heinlein was doing with wry, understated humor. Thus, I would argue, Robert A. Heinlein bears no real responsibility for these sorry products of his misguided admirers; we have allowed these stories to appear, and to borrow legitimacy from the author who inspired them, because we have failed to correctly interpret what this complex and talented writer was actually doing in the final decades of his career. And the joke is on us.

Gary Westfahl’s works include the Hugo-nominated Science Fiction Quotations: From the Inner Mind to the Outer Limits (2005) and The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy (2005); samples from these and his other works are available at his World of Westfahl website. His recent books include two books on science fiction films, The Spacesuit Film: A History, 1918-1969 (2012) and the just-published A Sense-of-Wonderful Century: Explorations of Science Fiction and Fantasy Films (2012).

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- HarperTeen Impulse Launch Next →

You May Also Like...

Kim Stanley Robinson: Making Worlds

Adrian Tchaikovsky: From Star to Star

Spotlight on: Sana Takeda

35 thoughts on “ the joke is on us: the two careers of robert a. heinlein ”.

An interesting analysis, to be sure – but if you’re going to call Have Space Suit – Will Travel an inflection point in Heinlein’s career, you ought to specify that Kip Russell himself is aware throughout that he’s the protagonist of a very improbable story, and makes this known periodically in his narration – sometimes with overt satire of the situation, such as the dream he recounts in chapter 5 (“…Will Tristan return to Iseult? Will Peewee find her dolly? Tune in this channel tomorrow…”).

The only other point I’d add is that James J. Garsch in Citizen of the Galaxy has always seemed a proto-Jubal Harshaw to me, despite falling on the “before” side of your threshold.

(I first read all three – Citizen, Space Suit, and Stranger – before age 14, the first two in my junior h.s. library.)

Heinlein was rather less worshipful of the military than many of the writers he influenced. He once described the army as “a permanent organization for the destruction of life and property.” An astute judgment—and one that genuine libertarians will appreciate.

Gary, you are unquestionably onto something. I have a lot of suggestions for you if you want to follow up on them. I will just make one comment here: the other two of the “big three,” Asimov & Clarke, definitely were sea-changed by Sputnik & that event has a before/after effect on science fiction as a whole. Thanks!

Thank you for a well-thought essay. I agree with most of your conclusions and feel that you have accurately snared and crystalised the feelings of many serious fans; however I believe and have believed since first-reading that “Farnham’s Freehold” is Heinlein at his hallucinogenic and visceral best.

I’m not sure where Gary Westfahl would shoehorn I WILL FEAR NO EVIL into his pattern. Heinlein, there, seems to be (paraphrasing Himself) looking at the present through the future. Screeds carried forward from SPACESUIT about inadequte education now predict a future where most of America is illiterate. Late 1960s anti-war street violence and its blowback create an America divided into the enclaved and the abandoned. Media serves only to pacify and mislead the uninformed. Yet yoga, meditation, and body painting — even living off the grid– come across as culturally positive. Heinlein would now seem both partially prescient and trapped in the trends of the late-1960s, as seen looking down from the vantage point of privileged class paranoia. EVIL seems a break-point in Heinlein’s career that Westfahl ignores, in that after it, after Heinlein’s near death, his work grows increasingly “autobiographical”, explicitly conflating his “Heinlein” character with his Lazarus Long character, particularly in TIME ENOUGH FOR LOVE. When he wrote BEYOND THIS HORIZON, under the foreseen shadow of the coming war, Heinlein threw in everything — economic and social speculation, as well as metaphysical speculation — as if it were his last novel, the capstone of his career. TIME ENOUGH FOR LOVE seems another such, written under the shadow of mortality. (Compare the start of HORIZON’s Chapter Ten with TIME ENOUGH’s Coda II.) That out of the way, Heinlein seems to allow himself to look backward, to revisit (and revel in) the/his past. He tips his hat to his antecedents (Roy Rockwell, L. Frank Baum, E. E. Smith) and his descendents (Poul Anderson, Gordon R. Dickson, etc.) in THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST. (Can a novel beginning “He’s a Mad Scientist and I’m his Beautiful Daughter” be meant as anything but fun?) He revisits “Gulf” in FRIDAY, flipping a story about a human becoming superhuman into a superhuman becoming human (a kind of version, too, of CITIZEN OF THE GALAXY’s search across subcultures for community/family). JOB: A COMEDY OF JUSTICE seems the closest to his early UNKNOWN/UNKNOWN WORLDS work, as well as a rework of the world-skipping of FARNHAM’S FREEHOLD into a “the man who learned better” plot. THE CAT WHO WALKS THROUGH WALLS revisits THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS and TIME ENOUGH FOR LOVE. TO SAIL BEYOND THE SUNSET not only revisits CAT and TIME, but all but hangs a sign proclaiming “I am working in the didactic/satiric tradition of Mark Twain” around its neck. Most of these post-TIME novels (save JOB) use an intrigue/action opening to hook readers into hearing Heinlein’s harangues, and close (like many of Baum’s OZ novels) with all the familiar characters having a party (in the Emerald City or on Tertius) to celebrate the adventures being over. Westfahl’s breaking of Heinlein’s career into pre- and post-1957 should also aknowledge that the post-1957 career should itself be considered up to 1970 and after 1970. p.s.: The best echo of Heinlein’s later novels is Connie Willis’s novella “Inside Job”, where she switches out Twain’s didactic satire for H. L. Menken’s rational skepticism.

Thanks for the article.

I know people who knew Heinlein and the biggest problem is people writing on him who never talked to him or those who knew him closely–or don’t read his own statements and literary work closely ( anyone who thinks Starship Troopers is about the military misses the point). Ignoring that he had a libertarian then formally Libertarian philosophy all his life is one problem; he also said his work was effectively censored until the 60’s.

For info on people using voluntary Libertarian tools on similar and other issues worldwide, please see the non-partisan Libertarian International Organization @ http://www.Libertarian-International.org ….

“Sputnik clearly indicated that Heinlein and other science fiction writers had succeeded in achieving this goal: humans were finally venturing into the cosmos, and everyone in the science fiction community had long been confident that, once space exploration had started, further progress to the Moon, Mars, and beyond was virtually inevitable.”

Ironically that sort of technologically progressive “space age” ended 40 years ago with the last Apollo mission to the moon.

It must suck for still-living science fiction writers born in the 1930’s and 1940’s, like Niven, Pournelle, Bova, Benford and Vinge, who grew up reading Heinlein, Asimov & Clarke, witnessed the moon landings in the 1960’s, and started their literary careers decades ago on the premise that we had entered a new era based on moving people off the planet. Now, in our mysterious, far-future 2012, they realize that the “space age” they had pinned their hopes and dreams on failed a couple of generations ago.

Thank you. I don’t know if you are right, but any theory that explains Heinlein’s later work is welcome.

Pingback: Saving Robert Heinlein « Gerry Canavan

I think you need to read “Grumbles from the Grave” again.

I’ve one problem concerning “Citizen of the Galaxy”: It is such a straightforward parody of Kipling’s “Kim” in its early chapters, that it must be seen as a fulcrum where the madcap ride into self-parody is concerned.

Consider: Bob Heinlein actually was a Libertarian. “Stranger in a Strange Land” came out after he read Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged.” “Stranger in a Strange Land” also was published 9 years after the Church of Scientology was founded – by another science fiction author.

I believe RAH knew and made use of parody as a teaching tool. Parody and other forms of humor are often the best way to transmit serious lessons about the human condition – especially politics, religion, and sex. I am fairly certain he also figured out that “science fiction” is not a genre – it is a setting. There is no such thing as a “pure” science fiction story – they are all “mystery,” “adventure,” “thriller,” “drama,” “comedy,” etc (or some combination of genres).

Almost spot on Gary, and I’d only amend it by saying it has been my theory that after his earlier successes RAH didn’t feel the need to bow to any editor and wrote whatever the hell he wanted, with his critics upset that he was not content to work in the same vernacular as before. Publishers also knew whatever had the Heinlein name on it would sell so they stopped editing him.

Pingback: A Provocative Theory: Heinlein turned to satire halfway through his career

I like your two-period theory of Heinlein’s work. But based on the evidence you offer, I’m not sure I’d describe the second period as intentional satires on science fiction. In your description of the second period, I would tend to emphasize the following: Heinlein was always concerned with the bottom line; Heinlein watched Hubbard grow rich; the character of the sagebrush sage named Robert A. Heinlein becomes increasingly prominent. In my reading of his later work, instead of writing satires, he was simply writing to make money, and he learned that people would buy books that purported to be science fiction novels but which increasingly promoted a Randian political agenda and loose social views.

The analogy with Scientology is very good indeed. But as with L. Ron Hubbard, it becomes difficult to know at what point the whole venture changed from tongue-in-cheek to deadly serious. I tend to think that as time went on, Heinlein really believed the political and social views he put into the novels; i.e., he drank his own Kool-Aid. Which would mean the novels weren’t satires, they were serious. Which is kind of sad.

Pingback: Author IVIS BO DAVIS | Xterra - Series | Science Fiction Novels | Sci-Fi Books

your astute line: “jokes without punchlines” reminded me of some recent scholarship on the Book of Revelations that holds the letters were written as coded political commentary/news but, in the hands of highly conservative readers, has been mistaken for literal prophecy. more on that here: http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2012/03/05/120305crbo_books_gopnik

also, i wish this essay were longer. thanks!

Interesting essay, that does explain much of the latter-day Heinlein work…but “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” seems serious enough in tone to not quite fit the theory. (The theory does fit some of Heinlein’s 1950s “adult” novels, like “Double Star” and “The Door into Summer,” which seem in many ways precursors to the later, longer novels…)

Also…I gather that “Stranger in a Strange Land” was something Heinlein wrote, on and off, from 1950 to its publication, from an outline prepared at the start and followed closely. Does that mean that it bears signs of being more serious at points earlier on? (Perhaps that’s why I’m not as fond of it as others seem to be…its “enlarged [[posthumous] edition” seemed a smoother read than the original).

You might want to consider that a wave of celebrities, writers and intellectuals got dosed with then new and legal LSD 25 around that time…

In response to Gary Westfahl’s thoughtful treatise – The Joke Is on Us: The Two Careers of Robert A. Heinlein – while it’s impossible to really know the thoughts and motivations of an author, such speculations are curiously thought provoking. I would like to offer Gary friendly thanks for his insight and offer a simpler explanation of Heinlein’s work. Robert was a scientific and mathematical genius. In terms of technology, he invented quite a number of things that have since come into production, including the water bed and cell phones, and foresaw and successfully depicted a lot of space-related devices and applications. Such technology was the basis for the science in his science fiction, and I applaud his visionary foresight. Heinlein placed these innovations in delightful and exceptionally well-written stories. However, there was a deeper and somewhat darker side of Mr. Heinlein that might best be characterized as socially prophetic. He was a dedicated student of human nature and social evolution, which expanded to the point he needed novel length space to describe it. He imagined in the fifties the social chaos he described as ‘The Crazy Years’, which began in the 1960s and continues to this day. He watched the moral, ethical, religious and governmental decline of the world, declaring that the U.S. would fall as a nation… with tragic results. That prophecy – for lack of a better term – is, in fact, upon us. Although I love his writing, some might declare him a sexual deviant, and I’m not comfortable with his depiction of incest as a socially acceptable behavior. But that, too, has come to pass, as Japanese ‘cable entertainment’ has game shows where contestants claiming to be actual families publicly engage in sexual intercourse between family members to win prizes. No, I think Robert’s keen view of mankind saw things he didn’t like of the broken human nature, and within the confines of his genre, he rather gently waved the red flag of warning while there was still blood in his veins and ink in his pen. As difficult as it is to be so openly aware of the danger of changing social values, perhaps we should all be so far-sighted and bold.

Ivis Bo Davis Author, Xterra Conspiracy and Xterra Escape http://www.ivisbodavis.com

Out of curiosity, is the “broad impact on the genre” of Heinlein’s work felt much outside of the US? A lot of his work has a US Depression era mix of folksiness and attitude (“I’m a hard-headed realist, unlike all those fuzzy-headed New Dealers”), kind of the opposite pole from Ray Bradbury’s Depression era romanticism. It’s hard to see that having much appeal outside the US, but who knows. For that matter, it’s hard to see it having more than a very limited appeal inside the US after around the early 1970s, but apparently it still is pretty popular here. Heinlein wrote some enjoyable novels and short stories, like Asimov and Clarke, but they’ve been outclassed by the best of the writers in succeeding generations.

Pingback: Annoyed With The History of Science Fiction « Ruthless Culture

@Paul – surely you must realize that “outclassed” is entirely subjective in multiple ways: outclassed in imagination? Originality? Impact on society? Number of books published? Number of books sold? Writing style? Craftmanship? (And for the record, I don’t agree with your assessment on any of the above. There are some fine writers working today and much of their work is built on the foundation laid down by those you think outclasses.)

Gary – this was an interesting read and a provocative theory, but I ‘sense’ one possible flaw: you wrote – “Some will protest that the usually-candid Heinlein never stated or hinted, in interviews and speeches during the final decades of his life, that any of his novels and the viewpoints therein were less than entirely serious – but that is only what we would expect, considering the one characteristic of Heinlein that everyone can agree was a constant throughout his entire career: an overriding concern for the bottom line. If Heinlein was receiving enthusiastic fan letters about the life-transforming effects of the philosophies in his recent novels, and if healthy sales figures indicated that such reactions were commonplace, Heinlein was far too wise to disrupt the flow of income into his bank account by suggesting that, actually, his tongue had been firmly in his cheek.”

You suggest that when readers failed to get the joke, Heinlein ratcheted up open the satire. But if your theory holds true, then what Heinlein was actually doing was “hoping to get caught”. If he had gotten called out, it certainly wouldn’t have been good for his bottom line, a sacrosanct subject. Your theory would then seem to suggest that RAH was not aware that he was engaging in potentially self-destructive behavior. So either he wasn’t consciously satirizing, or he wasn’t satirizing as your piece suggests. OR – he was consciously satirizing, HOPING that he would get called out so that he could stop writing in a field he’d obviously become disenchanted with and his fans let him down. Somehow I just don’t feel comfortable with any of those scenarios.

I think this is quite a shabby piece of scholarship.

a) ‘He was being ironic’ is neither an interpretation nor a theory… it’s an apology.

b) You’re issuing an apology for a man who clearly thought that society was a little too oppressive when it came to child abuse.

Given what is now known about the Catholic Church, the BBC and a number of other institutions’ tendency to look the other way when people started doing stuff to kids and this summer’s netstorm over the attempt by some elements at Readercon to soft-pedal the response to a fan’s sexual harassment of an author, I don’t think that serious genre criticism should be in the business of lazily saying “I’m sure he was kidding” when a respected member of the field writes a book about how it’s okay to fuck an 11-year old girl.

Pingback: Linkspam, 11/30/12 Edition — Radish Reviews

Pingback: Is Heinlein’s Have Space Suit-Will Travel Satire? « Auxiliary Memory

“Out of curiosity, is the “broad impact on the genre” of Heinlein’s work felt much outside of the US? ”

No. The belief in Heinlein’s supremacy appears to be very much an American perspective. From a global perspective, the two most famous SF authors of all time are H.G. Wells (‘The War of the Worlds’ remains highly-read and relevant, with a recent major film adaptation keeping it in the public mind) and Arthur C. Clarke. The latter has a slight caveat, in that Clarke’s fame mostly stems from 2001: A Space Odyssey which is no longer as widely watched by young SF fans as it was even a decade or two ago, but it still remains one of the most famous works of SF ever produced (in terms of public perception, way more famous and influential than any work of Heinlein’s). However, Clarke’s overall impact is secure due to his real-life science work in radar and publishing research that led directly to the creation of geostationary satelliters and asteroid-detection programmes.

From the UK perspective, little of Heinlein’s work remains in print (I believe Stranger, Moon and Starship Troopers are his only works currently available) and his influence seems to be, at best, no greater than Clarke, Herbert, Asimov or Dick (all of whom I would argue are better-known here in the UK than Heinlein) and from a populist viewpoint he’d only be recognised in conjunction with the Verhoeven Troopers film. And given that was 15 years ago, even that’s going to be a bit tenuous.

An important author in the history of the genre, certainly, but his modern-day influence and impact is fairly minimal outside of the United States, and I don’t think that prevalent any more within it.

Yes, especially in Japan, both during his life and afterward, including significant influences on Japan’s leading manga and anime creatives. Probably the most faithful live-action movie adaption of a Heinlein novel was recently made in Japan, as well as both anime and manga versions of some of his other works. Also fairly popular in Germany, and moderately so in France.

Pingback: Robert Heinlein: Time for the stars | books we have read

Seems to be making the argument that if one descends into self-parody by choice, rather than due to a dearth of ideas, that this should be embraced as a relevant form of creativity. Thing is, ultimately, the intent of the author is nearly meaningless next to the effect experienced by the reader. Even if one acknowledges satiric intent on the part of Heinlein, it should be equally acknowledged that the execution of said satire has resulted in a negative reaction by many readers — and not just critics. When the defense against “This is crap, he must’ve lost his mind!” is “Oh no, he KNEW what he was doing,” one might wonder if that apologia makes the author and his work look better or worse. [Having said that, I’d like to note that I liked Farnham’s Freehold (at least I did when I read it at age 14) Podkayne of Mars (the only novel other than The Hobbit that I’ve read three times) TMIAHM and Job: A Comedy of Justice.]

Pingback: Geek Media Round-Up: December 4, 2012 – Grasping for the Wind

Problem = I don’t see how the “Future History” novels of the 50s – Revolt in 2100 and Methuselah’s Children – fit the scheme. These are most definitely not juvenile novels and show an appreciation of the role of religion in populism that resonates today. The way Lazarus Long evolved as a character does fit, but nothing else does.

It is too bad Heinlein didn’t finish the “Future History” series. As he says in Revolt, he simply couldn’t bring himself to write The Sound of His Wings and the sequels because he found Nehemiah Scudder so repugnant as a character. These books would have been seen as truly prophetic (no pun intended) today.

I left out For Us, The Living on purpose since it wasn’t published in Heinlein’s lifetime, but it also doesn’t fit. Would anyone who was largely consumed by space operas write that book? I doubt it.

I think what happened was that Heinlein found that writing the juvenile books paid off, big time. He always had his eye on the main chance when it came to earning a living and I think he took the rejection of For Us, The Living as a signal that there weren’t readers for his more serious work. But here I’m speculating.

Given that Heinlein was a huge fan of James Branch Cabell, it is not surprising that when he could finally write to suit himself, he wrote a kind of ironic satire fantasy similar to that Cabell had written. Perhaps ‘Glory Road’ best foreshadowed this; it satirizes the traditional hero–and fantasy hero specifically–from start to finish. What DOES a retired hero DO? He becomes an ornament, reversing the traditional fantasy role of the rescued Princess, who marries with stars in her eyes and has babies and never does another noteworthy thing, not even designing bad jewelry. Lovely irony and satire, just lovely.

It took me years to truly enjoy the late ‘Middle’ Heinlein and ‘Late’ Heinlein; I desperately wanted them to be more of his early work, say, through “The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress’. (To this day cannot reread “I Will Fear No Evil’–Nembutal with a side of opium is an upper in comparison).

I have not tried Cabell for nearly half a century, but your essay makes me think I should give him another try. Perhaps I was simply to unsophisticated to appreciate him earlier; certainly I was too unsophisticated and inexperienced to appreciate Heinlein post-‘Moon’ until my late forties.

Thank you for a thought-provoking piece.

I realize this is several years old. I enjoyed reading it, however. Thanks!

I originally replied on November 25, 2012, when this article was published online. Something happened since then that changed my thinking about Heinlein: the massive two-volume biography by William H. Patterson, Jr., which I spent most of June 2014 reading. As much as Sputnik took him by surprise, it was a trip that Robert and Virginia Heinlein took to the Soviet Union in 1960 that finally convinced him America had to be woken up to its imminent destruction at the hands of the USSR. Everything he wrote after that had a right-wing political slant.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

SHOW THE LOVE!

Over 100,000 people will read these pages this month. If each of you gave $5, it would fund all of projects: the website, the magazine, and the Locus Awards. Donate directly here, OR go check out all the cool rewards we have for donors at our IndieGogo Fund Drive for 2024 .

THANK YOU FOR MAKING IT HAPPEN !

We use essential cookies to make our site work. With your consent, we may also use non-essential cookies to improve user experience, analyze website traffic, and serve ads to our users based on their visit to our sites and to other sites on the internet. By clicking “Accept,“ you agree to our website’s cookie use as described in our Cookie Policy . Users may opt out of personalized advertising by visiting Ads Settings.

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988)

Additional crew.

IMDbPro Starmeter See rank

- 1 win & 1 nomination

- based on the short story by

- based on the novel by

- creator: based on novel by (creator)

- based on the short story "All You Zombies" by

- novel "Starship Troopers"

- based on a novel by

- 44 episodes

- based upon a novel by

- novel "The Puppet Masters" (uncredited)

- story (as Robert Heinlein)

- technical advisor

- In-development projects at IMDbPro

Personal details

- Access to the complete works of Robert Heinelin

- Official website for the Robert Heinlein Foundation

- Author 'All You Zombies'

- July 7 , 1907

- Butler, Missouri, USA

- May 8 , 1988

- Carmel, California, USA (emphysema and congestive heart failure)

- Spouses Virginia Doris Gerstenfeld October 21, 1948 - May 8, 1988 (his death)

- Other works Novel: "Double Star" (first published in the UK by Michael Joseph Ltd.).

- 1 Interview

Did you know

- Trivia Robert A. Heinlein's first book was actually the last to be published. After his death a lost manuscript was discovered. "For Us, the Living" (1938?) was written before "Lifeline" but not published until 2003.

- Quotes "There ain't no such thing as a free lunch".

- The Grand Master

- When did Robert A. Heinlein die?

- How did Robert A. Heinlein die?

- How old was Robert A. Heinlein when he died?

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Add demo reel with IMDbPro

How much have you seen?

Recently viewed

'Star Trek's' Famous "Tribble" Episode Was a Sweet Ripoff

The little furry alien balls who make adorable noises have achieved legendary status among famous sci-fi creatures. But did you know they were kind of a ripoff?

Exactly 50 years ago today, the most famous Star Trek episode of all time — “The Trouble With Tribbles” — aired on for the first time. Since 1967, the little furry alien balls who make adorable noises and are born pregnant have achieved legendary status among famous sci-fi creatures. But did you know they were kind of a ripoff?

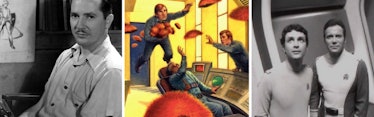

Though “The Trouble With Tribbles” was penned by the excellent science fiction writer David Gerrold , the concept for the critters themselves actually originated with author Robert Heinlein. Here’s what happened.

In Gerrold’s script, the crew of the starship Enterprise initially perceive that the Tribbles are cute innocuous furballs. However, as the story goes on, Spock and Bones figure out that the trouble with Tribbles is that they can’t stop reproducing. Ecologically, the Tribbles are a menace to the blue space wheat the Enterprise is trying to protect from Klingon sabotage. (Yep, back then the Klingons went undercover to screw with outer space crops.) And so, after the Enterprise and a local space station are overrun by the little critters, Scotty beams all the Tribbles into an engine of a Klingon ship, effectively murdering them because Scotty is hilarious.

Kirk has had it up to here with these damn Tribbles.

Regardless of what you think of that storyline, “The Trouble With Tribbles” became, and remains, the most popular Star Trek episode of all time. This is not the same as saying its the best , just that it’s been voted the most popular of the original series over and over again for five decades. But maybe that’s with good reason. In Edward Gross and Mark Altman’s oral history of Star Trek, The Fifty Year Mission , Gerrold is quoted as saying “…I set out to write the very best episode of Star Trek ever made.”

So, where’s the ripoff? Turns out, the Tribbles are very similar to creatures called “flat cats,” a martian animal from Robert A. Heinlein’s novel The Rolling Stones , published in 1952. Heinlein is, of course, a juggernaut in the field of early science fiction in America, famous for writing Stranger in a Strange Land , Starship Troopers , and possibly inventing the idea of “Bootstraps Paradox” with his short story, “All You Zombies.” In The Rolling Stones , the flat cats are similar to Tribbles insofar as they reproduce like crazy and cause some space-faring folk more than a few headaches.

But, when the Trek studio heads at Paramount and Desilu brought the possible plagiarism to Heinlein’s attention, the author barely minded. In fact, according to his estate and Gerrold, Heinlein just asked for one thing as compensation: a copy of the script, autographed by David Gerrold.

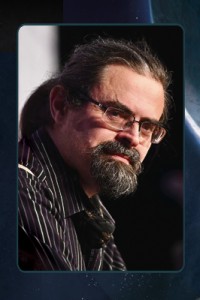

LEFT: Robert Heinlein. CENTER: Paperback cover of 'The Rolling Stones.' RIGHT: David Gerrold with William Shatner on the set of 'Star Trek: The Motion Picture.'

Gerrold, of course, didn’t intend to ripoff off Heinlein, and Heinlein was big-hearted enough to not mind an accidental homage to his flap cats in the creation of the Tribbles.

So, if you rewatch “The Trouble With Tribbles” today, in honor of its birthday, just try to imagine the buttoned-up author of Starship Troopers being delighted to receive an autographed copy of the teleplay in the mail. It will make you smile just as much as all those Tribbles falling on Captain Kirk.

Editor’s note(1/1/2018): Since the publication of this article, fans of both Star Trek and Heinlein have contacted Inverse and pointed out two bits of information that puts the Tribble rip-off in a slightly different light. First, according to the fact-checker hired by the original Star Trek — Kellam de Forest — Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and producer Gene L. Coon were both aware of the possibility of a plagiarism claim prior to the episode being filmed. Second, as revealed in the authorized biography of Robert Heinlein , Heinlein was less-than-pleased when Gerrold sold toy versions of the Tribbles at science fiction conventions. Merchandising hadn’t been covered in the “gentlemen’s agreement” between himself and Coon, making Heinlein feel, in retrospect, that his good nature had been taken advantage of. Thanks to our readers for keeping us honest.

The original Star Trek is streaming on CBS All Access and Netflix.

- Science Fiction

- FAQ: Heinlein the Person

- FAQ: Heinlein, His Works

- Heinlein Concordance

- Centennial July 7, 2007

- The Heinleins

- Heinlein Today News

- Latest News

- Newsletters

- Reviews of Heinlein Works

- Reviews of Related Works

- Prophets of Science Fiction Reviewed

- NexusForum Archive

- Pay It Forward

- Pay It Forward News

- Blood Drive Reports

- Heinlein For Heroes

- Scholarship Fund

- Scholarship News

- Educator’s Digital Download

- Education News

- Donate to the Heinlein Society

- Donate and Receive The Ensign’s Prize Books

- Planned Giving

- My Account (Login/Register/Renew Subscription Membership)

- Member News

- Heinlein Society Shop (Renew from My Account!)

- Legal Notices

- Directors & Committee Chairs

- Board of Advisors

- Readers Group

- Conventions

- Heinlein Centennial

- Family Meeting of 2012

- Purchase Issues

- Subscription Information

- Submission Guidelines

- About Bill Patterson

- Register First/Login

- Join Us in The Heinlein Society

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions about Robert A. Heinlein, his works

Heinlein Society

Updated Feb. 2013 and reviewed by William Patterson, Robert James, PhD and J.H. Seltzer.

©2003-2013 – no reproduction or distribution without consent of author. This material may not be copied and put on another website without permission.

Where can I find free copies of Heinlein’s books and stories to read on the Web?

You can’t. Hopefully, that is. Any free or unauthorized electronic versions of Heinlein’s works that appear on the Web are pirated (meaning: stolen) copies and the copyright owners will stomp on them as soon as possible. Go to Amazon [Link= http://www.amazon.com/Farmer-Sky-Robert-A-Heinlein/dp/0345324382/ref=pd_rhf_sc_s_cp_2_JG80 ] or AbeBooks.com [Link: http://www.abebooks.com/?cm_mmc=ggl-_-US_AbeBooks_Brand-_-Top+Brand-_-abebooks&gclid=CJfmpPe1jLUCFexxQgodaAsAfA ] or Apple or Barnes and Noble to buy copies or go to your library. You can also go to many of the publisher’s websites such as Baen Books and there are also book clubs and Sci-Fi book clubs. Many also offer a feature that allows you read a chapter (some less) without a purchase. Amazon has a feature called LOOK INSIDE that allows you to look inside for a pre-purchase read. This may be seen on the book cover display. And many also have a feature that allows readers to rate the book and leave comments. Times have never been better for the reader.

When Heinlein’s works are pirated, the theft is from all of us, and from the future, as the proceeds from sales of Heinlein’s works go directly and substantively to our future in space. The Heinlein Prize Trust is using income from Heinlein’s works to fund an award that encourages advancement in commercial space programs, as well as other worthy endeavors. The Heinleins, even after their deaths, are still “paying forward” to all of us, and it is our duty to honor their tremendous gifts to us by respecting the copyrights of Heinlein’s works and only purchasing authorized copies.

See: The Heinlein Prize [Link=http://www.heinleinprize.com/index.php]

Under what pseudonyms did Heinlein’s sf/f stories appear?

Anson MacDonald (Anson is Heinlein’s middle name and a Heinlein family name; MacDonald was wife Leslyn’s maiden name, but this is a coincidence: John Campbell, who liked all things Scottish, chose the name before he knew about Leslyn’s maiden name.)

Lyle Monroe (Lyle was his mother’s maiden name, and Monroe was a branch of his mother’s family. Just as Heinlein’s personal names were taken from grandfathers, so was Lyle Monroe — another set of grandfathers.)

John Riverside (probably from Riverside, California)

Caleb Saunders — there are a couple of sources from which “Caleb” might have been drawn: Heinlein’s best friend from the Naval Academy was Caleb Laning; one of his favorite books in the 1930’s was Caleb Catlum’s America (Vincent McHugh 1936). A source for “Saunders” is not known.

Simon York – They Do It with Mirrors. This was his only detective story. He said detective stories were easy to write but of lower market value than SF.

Are there any unpublished Heinlein novels?

When Heinlein died in 1988, there were a number of unpublished works in his files. Mrs. Heinlein prepared How to Be a Politician (1946) for publication in 1993 as Take Back Your Government!, and his travel book Tramp-Royale (1954). There was also a long-unsold manuscript for a utopian political novel, written in 1938, For Us, the Living , which the Heinleins thought to suppress because its writing was unacceptably crude by comparison to Heinlein’s later prose and in any case much of its idea content had been re-used in other stories, particularly the Future History. They destroyed all known copies — but one did survive and was recovered by Dr. Robert James [LINK: https://www.heinleinsociety.org/?s=last+of+the+wine. ] The book was published late in 2003.

Almost all of the remaining unpublished nonfiction has now been published — in the Robert A. Heinlein Centennial Souvenir Book [LINK: http://www.nitrosyncretic.com/ ] and in the Virginia Edition [LINK: http://www.virginiaedition.com ]

All that remains unpublished is the first sketch, written late 1977 while Heinlein was suffering from a blockage in his carotid artery, for the book that became The Number of the Beast (1980). The book is interesting, though not of Heinlein’s usual quality. There are currently no plans to publish The Panki-Barsoom Number of the Beast , though the manuscript is available for download at the online Heinlein Archive [LINK: http://www.heinleinarchives.net/upload/index.php?_a=viewProd&productId=441 ]

Did Charles Manson use “Stranger in a Strange Land” as his ‘bible’, and did the book connect to the Manson family murders?

No. This story apparently got started because of an attempt on the part of a San Francisco newspaper to cash in on the publicity surrounding the Tate-LaBianca murders in Los Angeles in August 1969. Even though the story had no actual research, it was picked up on the wire services and repeated in a report in Time magazine in January 1970, when Heinlein was dying from peritonitis. He did not see the article or the followups until months later, when he was able to attend to current affairs again.

The prosecutor of the “Manson Family” investigated the claim and dismissed it as without foundation.

Part of this factoid is that Heinlein had a lawyer investigate the claim. This is simply not true. J. Neil Schulman, a young writer and friend of Heinlein, undertook years later to contact Manson and ask him. Manson said (through an amanuensis) that he had never read the book (and in fact does not read for pleasure at all.) Nevertheless, some of the Manson girls had — and used names and other jargon from the book. One of Manson’s sons was named Valentine, and it is said that Manson called his parole officer (he had been in trouble with the law before the Tate-LaBianca killings) Jubal.

One of the Manson girls, probably Squeaky Fromme, had written to Heinlein for help when they were being rounded up in San Bernardino County after the murders. Heinlein investigated at the time but was told there was nothing he could do.

So there is a tangential and coincidental “connection” — but not through Manson, and certainly not as a blueprint for the Tate-LaBianca murders, which were part of Manson’s plan to bring on a race war he code-named “Helter-Skelter” (and this reference to a Beatles song was scrawled in blood at the Tate murder site). The connection of Stranger to the Tate-LaBianca murders was entirely made up to sell papers — and then books when an assistant prosecutor, Steven Kay, wrote a sensational book that included the made-up story.

How many Hugo awards does Heinlein have?

4 original Hugos and 3 Retro Hugos

The original Hugos were for:

1956 Novel: Double Star. Published 1956 by Robert A. Heinlein

1960 Novel: Starship Troopers. Published 1959 by Robert A. Heinlein

1962 Novel: Stranger in a Strange Land. Published 1961 by Robert A. Heinlein

1966 Novel: The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Published 1966 by Robert A. Heinlein

The Retro Hugos were started to cover works during the years before the Hugo awards were established. The Retro Hugos awarded at the 2001 World Con in Philadelphia (Millennium Philcon) for the Best Science Fiction and Fantasy writing of 1950 were:

Best Novel– Farmer in the Sky. Published 1950 by Robert A. Heinlein

Best Novella–“The Man Who Sold the Moon.” Published 1939 by Robert A. Heinlein (from The Man Who Sold the Moon )

Best Dramatic Presentation– Destination Moon movie (release date July 7, 1950) with script by Robert A. Heinlein and Alford van Ronkel

How many Nebula awards?

Heinlein received the first Grand Master Nebula award in 1975.

Was Heinlein a racist?

No. All evidence in both his writings and in his personal life indicates that Heinlein was a strong and aggressive anti -racist, and he was the first in many instances, to include Jewish, Black and Asian main characters in science fiction for this very reason.

The issue of racism first came up for his fiction with the post-war republication of Sixth Column in hardcover (followed by paperback publication as The Day After Tomorrow ). In that novel, the “Pan-Asian” invaders are combated by a super science ray which distinguishes the Pan-Asians from European (and other) Americans on the basis of racial biological differences. This was not detailed in the original 1941 publication, but when preparing the book Heinlein discovered a science article that suggested blood types fell out by racial groups, and he incorporated this into the revision. Later research invalidated this 1948 paper — but it was put in because it was cutting edge science, not for any racist reasons. Heinlein found the charge of racism offensive and took several opportunities to check whether Japanese themselves found it racist (most prominently the Japanese wife of biographer/critic Leon Stover, Takeko) — and was told it was not racist.

But the charge of racism is currently based on a very sloppy and insensitive reading of Farnham’s Freehold , a book in which a nominally Black future culture keeps white slaves and practices cannibalism. The book was written in 1963 and published in 1965, and it was a satire against the Cold War mythology that a nuclear war was “winnable,” using racial politics as a “test case.” Heinlein satirically portrayed the various apologists for slavery from the period ramping up to the American Civil War of 1861-1865, to the “limousine liberal” racism of the 1960’s in order to suggest that if the liberal values of America were destroyed in a nuclear holocaust, then mankind as a whole would revert to its “normal” behavior over the last 35000+ years, or which slavery and cannibalism are iconic pathologies.

Racists of the post-Civil Rights movement period believe Heinlein is saying “All Negros are like that,” when he is really saying “all of us human beings are like that.” — And it is the liberal values of the Enlightenment that stand between civilization and even the most cultivated savagery. (the cannibal rulers of the post-Holocaust world of Farnham’s Freehold are in fact not “black” or “African” at all, but rather an amalgamation of all the races of the southern Hemisphere).

What race is Eunice in “I Will Fear No Evil” ?

Reader’s choice–Heinlein apparently wrote the novel with pictures of two attractive women above his computer for inspiration, one white, one black, so that his language would not cue the reader to one or the other.

The popular opinion is that she was a woman of color.

What race or ethnicity is Juan Rico in “Starship Troopers”?

Filipino. There are few cues in the book until the end, except the abundance of Spanish names among young Johnny’s friends; but late in the book he mentions that the language spoken at his home was Tagalog, which is the most prominent language spoken in the Philippines.

What race is Rod Walker in “Tunnel in the Sky”?

Black. The clues are in the novel but Heinlein didn’t treat race in this novel as an “issue” and so writes all characters regardless of their sex or race as characters , on equal footing.

Heinlein Society member & Heinlein scholar/researcher, Robert James, Ph.D. explains further: The evidence is slim but definite. First and foremost, outside of the text, there is a letter in which RAH firmly states that Rod is black, and that Johnny Rico is Filipino. As to the text itself, it is implied rather than overt. RAH often played games with the skin color of his characters, in what I see as a disarming tactic against racists who may come to identify with the hero, then realize later on that they have identified with somebody they supposedly hate. He does this in a number of different places. Part of this may also have to do with the publishing mores of the time, which probably would not have let him get away with making his main character black in a juvenile novel. The most telling evidence is that everybody in “Tunnel” expects Rod to end up with Caroline, who is explicitly described as black. While that expectation may seem somewhat racist to us today, it would be a firm hint to the mindset of the fifties, which would have been opposed to interracial marriages. I think RAH himself would have been infuriated by the suggestion that this was racist; indeed, I think it more likely that this was simply the easiest way to signal a reader from the fifties that he’s been slipped a wonderful protagonist who is not white. I have taught this novel many times, and at least twice, a teenage student has asked me if Rod was black without me prompting the possibility whatsoever.

Was Heinlein a sexist?

It all depends on what you mean. Heinlein was a strong and proactive feminist comfortably within the mainstream of early 20 th century feminism. But the issues in feminism changed over time.

Deb Rule says: As a female who grew up reading Heinlein, my opinion is, yes, but in a good way. He believed in the strength, competence, and abilities of women to do or be whatever they chose, and his major female characters are usually portrayed as stronger and smarter than their male counterparts. He did seem to believe that women could still be powerful, in-control career women yet still be female , feminine, and could be–and want to be–mothers and wives. For a time this was regarded as anti-feminism, though that fashion in feminism evolved into something else later.

John Seltzer adds; If you wish to read a really good article about this topic get The Heinlein Journal No. 16, January 2005. [Link: https://www.heinleinsociety.org/heinlein-journal/ .] Look at Sex And Other Metaphors by Lisa Edmonds on page 37. This article was very helpful clearing this issue up for me.

From reading Heinlein’s books I’ve come to the conclusion he was a devote Christian/absolute atheist. Was he? What were Heinlein’s religious beliefs? Did he believe in an afterlife?

His religious beliefs were his own, personal and private and only subject to guesswork and opinion. He was raised a Methodist and in the non-fiction “Tramp Royale” claims Methodist as his religion as of that writing in 1953-54. One of his last novels, “Job: A Comedy of Justice” shows a deep and thorough knowledge of, and study of, the Christian Bible and beliefs, though this is coupled with a strongly satirical treatment of those beliefs. There are definite non-Christian religious — “esoteric” — elements in some of his stories, as is detailed in “The Hermetic Heinlein” in issue No. 1 of The Heinlein Journal . [Link: https://www.heinleinsociety.org/heinlein-journal/ .] Then there’s “Stranger in a Strange Land” with a tale of a messiah and the foundation of a new religion. The LDS religion often appears in his books (i.e. in Sixth Column and in “If This Goes On –“) and is generally portrayed positively.

The closest Heinlein came to revealing his own, personal opinion on religion and the afterlife comes from the introduction to Theodore Sturgeon’s “Godbody”.

From reading Heinlein’s books I’ve come to the conclusion he was a Fascist/Libertarian/liberal/conservative. Was he?

People with particular slants seem to latch onto one work or another that suits their opinions or biases and take it as being representative of all of Heinlein. “Starship Troopers” is regarded by some as ‘fascist’ (particularly after the hideous distortion presented in the movie version), it isn’t . “Stranger in a Strange Land” became a banner book for liberals–yet it was written at the same time as “Starship Troopers” so couple the contradictions together on that account. Libertarians adore “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” with the anarchistic type of society that works so well, yet Heinlein came along with “The Cat Who Walks Through Walls” and smashed that same perfect setup to bits, showing the potential unpleasant outcome. For every political or social stance you care to choose to assign to Heinlein you can probably find something in his writing to support that opinion… and something else to contradict it.

Robert was a master at creating images. To create an image he had to know his audience. Not just understand his audience but be his audience. From this point of view you could put any label on him and be somewhat correct. To an extent this is correct for any great writer.

Which version of “Stranger in a Strange Land” is better, the ‘as originally published’ or the later ‘uncut’ version, and why are there two versions?

See: Stranger VS Stranger [Link: https://www.heinleinsociety.org/2013/02/2210/ ] by G. E. Rule. Some people prefer the “tighter” storytelling of the 1961 version; others prefer the richer language of the uncut original version. In any case, it was the uncut original version that was put in the Virginia Edition. [Link: http://www.virginiaedition.com/titles.aspx ].

As of 2011, Bill Patterson is slowly compiling a “comparative” edition, extensively annotated, that shows both the original and the 1961 prose on the same page. However, due to the demands of the biography and the Journal, it is expected to be years before this comparative edition is available.

Is there a real Church of All Worlds ala “Stranger in a Strange Land”?

Yes, but Heinlein, himself, had nothing to do with it or its founding.

Did Poddy die at the end of “Podkayne of Mars?”

In Heinlein’s original writing, yes, she did, but the publisher objected so in was rewritten and published with Poddy surviving. Recently a new edition has been released with both endings.

Did Lazarus Long die at the end of “Time Enough For Love”?

Somewhat speculatively, yes he did, in the book’s original intent… until “Number of the Beast” was written and Lazarus appears therein, alive and well. So ultimately, the answer is “no,” Lazarus did not die, in some sense. Maybe the later book catches him at an earlier section of his personal timeline. Things get tricky when you do as much time-travel and time-looping as the Tellus Tertius group seems to do.

In a letter to a close friend Robert said he was going to kill off Lazarus. And so he did in Time Enough for Love . Did Robert bring him back because of pressure from his friends? Who knows? I’m glad he did. I like Lazarus.

Is Lazarus Long his own ancestor?

No. He does go back in time, meets and has intimate relations with his mother, but himself as a child is present as well in the story.

From “Time Enough For Love,” what does “E.F. or F.F” mean?

Eat First or F–k first. With the answer “both” making perfect sense.

What’s the best book to recommend to introduce someone to Heinlein?

The juveniles are usually safe bets. They’re good science fiction and good adventure without some of the more shocking and/or controversial elements of later novels. However, it’s an individual thing–I’ve met people who started with later novels like “Cat Who Walks Through Walls” and become enamored.

Unlike many I didn’t start reading Robert until later in life. My first try was Friday. After 100 pages I couldn’t go any further. The book didn’t keep my attention. About 3 years later I read Starship Troopers without any knowledge both books were written by Heinlein. Starship interested me and I read another of his books. After a couple more I read Heinlein like I was possessed. When I got to Friday again I didn’t recognize the book at all until about the 90 th page. It was then I remembered trying this book before. This time Friday interested me and today it is one of my favorites.

After reading all of Heinlein’s writings at random I went back and read them in order. Based on this experience I advise new readers to try to read his stories in the order written.

What are the “Lost Three” stories? What are the “Stinkeroos”?

These are three short stories published in the early 1940s and never collected into any of Heinlein’s books of short stories. Consequently, they could be rather hard to find until they were published in an SF Book Club Off the Main Sequence (2005) and then in the Virginia Edition. The stories are:

- Beyond Doubt , (co-author Elma Wentz), Astonishing Stories, April 1941, Republished in Beyond the End of Time (editor Fred Pohl, 1952), Political Science Fiction (editor Martin H. Greenberg and Patricia S. Warrick, 1974), Election Day 2084 (editor Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg, 1984).

- My Object All Sublime , Future, February 1942

- Pied Piper , Astonishing, March 1942 (never republished)

At one point in a letter to Campbell, Heinlein mentioned three “stinkeroos” he had not yet been able to sell. It was thought for a long time that it was these three stories he was referring to, although from context it appears that one of the stories he was talking about in that letter was “ Patterns of Possibility,” which was later sold and published as “Elsewhen.”

Which Star Trek episode(s) was Heinlein involved with, and why?

Heinlein wasn’t involved with any Star Trek episodes.

“The Trouble With Tribbles” –the producers noticed that the Tribbles bore a decided similarity to Heinlein’s Martian flatcats in “The Rolling Stones” and so asked Heinlein’s permission for the concept (according to “The Trouble With Tribbles” author David Gerrold). Heinlein asked only for an autographed copy of the script.

“The World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky.” In this Star Trek episode a number of people from another race were traveling to a new world. The vehicle is an asteroid. The ship was run and piloted by a computer and they were forbidden to know. The basic story line is very similar to “Orphans in the Sky.”

“Operation: Annihilate.” This Star Trek episode is similar to “Puppet Masters.” Alien creatures from space invade a planet inhabited by humans. Kirk’s brother and family are living on the planet. The creatures attach themselves onto the humans back and eventually the host dies.

From “Starship Troopers,” what is the origin and meaning of “Shines the name, shines the name of Roger Young”?

It’s from a ballad chronicling the real actions of an infantry private in World War II. Private Roger W. Young, 148th Regt. 37th Infantry Division, 25 years old, 5’2″ tall, with bad eyesight and nearly deaf, single-handedly attacked a Japanese machine gun nest that had his unit pinned down. Pvt. Young was killed. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Link:The Story of Roger Young

The Ballad of Rodger Young

PFC Frank Loesser

No, they’ve got no time for glory in the Infantry.No, they’ve got no use for praises loudly sung,But in every soldier’s heart in all the InfantryShines the name, shines the name of Rodger Young.Shines the name–Rodger Young!Fought and died for the men he marched among.To the everlasting glory of the InfantryLives the story of Private Rodger Young.

Caught in ambush lay a company of riflemen–

Just grenades against machine guns in the gloom–

Caught in ambush till this one of twenty riflemen

Volunteered, volunteered to meet his doom.

Volunteered, Rodger Young!

Fought and died for the men he marched among.

In the everlasting annals of the Infantry

Glows the last deed of Private Rodger Young.

It was he who drew the fire of the enemy

That a company of men might live to fight;

And before the deadly fire of the enemy

Stood the man, stood the man we hail tonight.

On the island of New Georgia in the Solomons,

Stands a simple wooden cross alone to tell

That beneath the silent coral of the Solomons,

Sleeps a man, sleeps a man remembered well.

Sleeps a man, Rodger Young,

In the everlasting spirit of the Infantry

Breathes the spirit of Private Rodger Young.

No, they’ve got no time for glory in the Infantry,

No, they’ve got no use for praises loudly sung,

But in every soldier’s heart in all the Infantry

Shines the name, shines the name of Rodger Young.

Shines the name–Rodger Young!

To the everlasting glory of the Infantry

Lives the story of Private Rodger Young

How much writing did Heinlein do on the Tom Corbett, Space Cadet TV series?

None. Not a line. He simply licensed the use of the name “space cadet” from the title of his 1948 book to the producers of the television show. He didn’t even take participation in merchandising.

At the time(1950-1952) there was no television reception in the mountains of Colorado Springs where he lived, so although the producers sent him courtesy copies of scripts, he didn’t even see an episode until the sponsor brought a few kinescopes to a conference at the nearby Broadmoor Hotel a year later. He was frankly appalled at the series.

What is Federal service in Starship Troopers?

The main question seems to be whether it was entirely military or entirely civilian or civilian with a military component (which would be not too different from what we have now). Different people have come down on different sides of this question. The most prominent of these arguments is James D. Gifford’s Essay “The Nature of Federal Service.” Gifford makes a case that Federal Service was essentially military in nature and that the Federation is therefore essentially a military state and that only military veterans can vote.

However, Heinlein said the direct opposite on many occasions, specifically that veterans of federal service are NOT military veterans. Cf. a personal reply to the author of a very unfair review of the book when it first appeared: “See pp. 43-48, where it is made clear that even an elderly, blind, wheelchair, female cripple must be accepted, and that any form of Federal service, military or non-military, wins franchise, and that most voters have had no military service.

Heinlein repeated this argument several times in correspondence. To this Gifford says that if he didn’t make it clear in the book, then these extra-textual comments don’t have any force and essentially cannot be used in evaluating the book.

The resolution to the conundrum is that Heinlein did, indeed, “make it clear” in the book, and that Gifford, standing in for this side of the argument, brings to his interpretation extra-textual assumptions about what “military” means.

Bill Patterson suspects that the world of Starship Troopers is based on the early-20 th century conception of a Wellsian Managerial-Socialist state (or perhaps closer to Edward Bellamy’s world in Looking Backward — a book that was so highly influential on Heinlein’s political thought that he used it as the basis of his own first novel, For Us the Living) which has a military arm, but the federal service that is a requirement for franchise is service to the state, not to the military specifically. The situation is somewhat confused because THEY do not make the same distinction we do between military and non-military service. You go where you are needed, and if they have need for military personnel, your federal service may assign you to a military occupation; otherwise it will be non-military in nature. Heinlein takes pains to point this out in his list of occupations one might be sent to when Rico first tries to enlist.

It would be more correct that only retired civil servants could exercise the franchise — and that some of those civil servants (about 5% according to Heinlein’s own representations at another place) were engaged in military activities, while 95% were in other occupations, of the type we characterize as “civilian.”

How much of Stranger did Heinlein take seriously — and in what ways?

Depends on what you mean by “seriously.” The book is a satire, and so he used it all for purposes of supporting the satire — but that does not mean he did not think the ideas he was talking about were unimportant. But they are there for the satirical purpose — which he explained to his editor involved turning our cultural assumptions upside down: “My purpose in this book was to examine every major axiom of the western culture, to question each axiom, throw doubt on it — and, if possible, to make the antithesis of each axiom appear a possible and perhaps desirable thing — rather than unthinkable . . . . Anything that I said . . . should, by definition of the problem, be shocking — or it wasn’t worth saying, since the purpose was to cast doubt on basic unconscious assumptions. Shock is comprised of surprise plus insecurity, with an instinctive desire to fight back, deny the attack, restore the feeling of security.”