How Do Conjugal Visits Work?

Maintaining close ties with loved ones while doing time can increase the chances of a successful reentry program. Although several studies back this conclusion, it’s widely logical.

While the conjugal visits concept sounds commendable, there’s an increasing call to scrap the scheme, particularly across US states. This campaign has frustrated many states out of the program, leaving only a handful. Back in 1993, 17 US states recognized conjugal visits. Today, in 2020, only four do.

The conjugal visit was first practiced in Mississippi. The state, then, brought in prostitutes for inmates. The program continued until 2014. The scrap provoked massive protests from different right groups and prisoners’ families. The protesters sought a continuance of the program, which they said had so far helped sustain family bonds and inmate’s general attitude to life-after-jail.

New Mexico, the last to scrap the concept, did so after a convicted murderer impregnated four different women in prison. If these visits look as cool as many theories postulate, why the anti-conjugal-visit campaigns in countries like the US?

This article provides an in-depth guide on how conjugal visits work, states that allow conjugal visits, its historical background, arguments for and against the scheme, and what a conjugal visit entails in reality.

What Is a Conjugal Visit?

A conjugal visit is a popular practice that allows inmates to spend time alone with their loved one(s), particularly a significant other, while incarcerated. By implication, and candidly, conjugal visits afford prisoners an opportunity to, among other things, engage their significant other sexually.

However, in actual content, such visits go beyond just sex. Most eligible prisoners do not even consider intimacy during such visits. In many cases, it’s all about ‘hosting’ family members and sustaining family bonds while they serve time. In fact, in some jurisdictions, New York, for example, spouses are not involved in more than half of such visits. But how did it all start?

History of Conjugal Visits

Conjugal visits origin dates back to the early 20 th century, in the then Parchman Farm – presently, Mississippi State Penitentiary. Back then, ‘qualified’ male prisoners were allowed to enjoy intimacy with prostitutes, primarily as a reward for hard work.

While underperforming prisoners were beaten, the well-behaved were rewarded in different forms, including a sex worker’s company. On their off-days, Sunday, a vehicle-load of women were brought into the facility and offered to the best behaved. The policy was soon reviewed, substituting prostitutes for inmates’ wives or girlfriends, as they wished.

The handwork-for-sex concept recorded tremendous success, and over time, about a quarter of the entire US states had introduced the practice. In no time, many other countries copied the initiative for their prisons.

Although the United States is gradually phasing out conjugal visits, the practice still holds in many countries. In Canada, for instance, “extended family visits” – a newly branded phrase for conjugal visits – permits prisoners up to 72 hours alone with their loved ones, once in few months. Close family ties and, in a few cases, friends are allowed to time alone with a prisoner. Items, like foods, used during the visit are provided by the visitors or the host – the inmate.

Over to Asia, Saudi Arabia is, arguably, one of the most generous countries when it comes to conjugal visits. Over there, inmates are allowed intimacy once monthly. Convicts with multiple wives get access to all their wives – one wife, monthly. Even more, the government foots traveling experiences for the visitors.

Conjugal visits do not exist in Great Britain. However, in some instances, prisoners incarcerated for a long period may qualify to embark on a ‘family leave’ for a short duration. This is applicable mainly for inmates whose records suggest a low risk of committing crimes outside the facility.

This practice is designed to reconnect the inmates to the real world outside the prison walls before their release . Inmates leverage on this privilege not just to reconnect with friends and family, but to also search for jobs , accommodation, and more, setting the pace for their reintegration.

Back to US history, the family visit initiative soon began to decline from around the ’80s. Now, conjugal visits only exist in California, New York, Connecticut, and Washington.

Is the Increasing Cancellation Justifiable?

The conjugal visit initiative cancellation, despite promising results, was reportedly tied around public opinion. Around the ’90s, increasing pressure mounted against the practice.

One of the arguments was that convicts are sent to jail as a punishment, not for pleasure. They fail to understand that certain convictions – such as convictions for violent crimes – do not qualify for conjugal visit programs.

The anti-conjugal visit campaigners claim the practice encouraged an increase in babies fathered by inmates. There are, however, no data to substantiate such claims. Besides, inmates are usually given free contraceptives during the family visits.

Another widely touted justification, which seems the strongest, is the high running cost. Until New Mexico recently scraped the conjugal visit scheme, they had spent an average of approximately $120,000 annually. While this may sound like a lot, what then can we say of the approximately $35,540 spent annually on each inmate in federal facilities?

If the total cost of running the state’s conjugal visit program was but equivalent to the cost of keeping three inmates behind bars, then, perhaps, the scrap had some political undertones, not entirely running cost, as purported.

Besides, an old study on the population of New York’s inmates postulates that prisoners who kept ties with loved ones were about 70 percent less likely – compared to their counterparts who had no such privilege – to become repeat offenders within three years after release.

Conjugal Visit State-by-State Rules

The activities surrounding conjugal visits are widely similar across jurisdictions. That said, the different states have individual requirements for family visitation:

California: If you’re visiting a loved one in a correctional facility in California, among other rules , be ready for a once-in-four-hours search.

Connecticut : To qualify, prisoners must not be below level 4 in close custody. Close custody levels – usually on a 1-to-5 scale – measures the extent to which correctional officers monitor inmates’ day-to-day activities.

Also, inmates should not be on restriction, must not be a gang member, and must have no records of disciplinary offenses in Classes A or B in the past year. Besides, spouse-only visits are prohibited; an eligible member of the family must be involved.

New York : Unlike Connecticut and Washington, New York’s conjugal visit rules – as with California’s – allow same-sex partners, however, not without marriage proof.

Washington : Washington is comparatively strict about her conjugal visit requirements . It enlists several crimes as basis for disqualifying inmates from enjoying such privileges. Besides, inmates must proof active involvement in a reintegration/rehabilitation scheme and must have served a minimum time, among others, to qualify.

However, the rule allows joint visits, where two relatives are in the same facility. Visit duration varies widely – between six hours to three days. The prison supervisor calls the shots on a case-to-case basis.

As with inmates, their visitors also have their share of eligibility requirements to satisfy for an extended family visit. For instance, visitors with pending criminal records may not qualify.

As complicated as the requirements seem, it can even get a bit more complex. For instance, there is usually a great deal of paperwork, background checks, and close supervision. Understandably, these are but to guide against anything implicating. Touchingly, the prisoners’ quests are simple. They only want to reconnect with those who give them happiness, love, and, importantly, hope for a good life outside the bars.

Conjugal Visits: A Typical Experience

Perhaps you’ve watched pretty similar practices in movies. But it’s entirely a different ball game in the real world. Besides that movies make the romantic visits seem like a trend presently, those in-prison sex scenes are not exactly what it is in reality.

How, then, does it work there? As mentioned, jurisdictions that still allow “extended family visits” may not grant the same to the following:

- Persons with questionable “prison behavior”

- Sex crime-related convicts

- Domestic violence convicts

- Convicts with a life sentence

Depending on the state, the visit duration lasts from one hour to up to 72 hours. Such visits can happen as frequently as once monthly, once a couple of months, or once in a year. The ‘meetings’ happen in small apartments, trailers, and related facilities designed specifically for the program.

In Connecticut, for example, the MacDougall-Walker correctional facility features structures designed to mimic typical home designs. For instance, the apartments each feature a living room with games, television, and DVD player. Over at Washington, only G-rated videos, that’s one considered suitable for general viewers, are allowed for family view in the conjugal facilities.

The kitchens are usually in good shape, and they permit both fresh and pre-cooked items. During an extended family visit in California, prisoners and their visitors are inspected at four-hour intervals, both night and day, till the visit ends.

Before the program was scrapped in New Mexico, correctional institutions filed-in inmates, and their visitors went through a thorough search. Following a stripped search, inmates were compelled to take a urine drug/alcohol test.

Better Understanding Conjugal Visits

Conjugal visits are designed to keep family ties.

New York’s term for the scheme – Family Reunion Program (FRP) – seems to explain its purpose better. For emphasis, the “R” means reunion, not reproduction, as the movies make it seem.

While sexual activities may be partly allowed, it’s primarily meant to bring a semblance of a typical family setting to inmates. Besides reunion, such schemes are designed to act as incentives to encourage inmates to be on their best behavior and comply with prison regulations.

Don’t Expect So Much Comf ort

As mentioned, an extended family visit happens in specially constructed cabins, trailers, or apartments. Too often, these spaces are half-occupied with supplies like soap, linens, condoms, etc. Such accommodations usually feature two bedrooms and a living room with basic games. While these provisions try to mimic a typical home, you shouldn’t expect so much comfort, and of course, remember your cell room is just across your entrance door.

Inmates Are Strip-Searched

Typically, prisoners are stripped in and out and often tested for drugs . In New York, for example, inmates who come out dirty on alcohol and drug tests get banned from the conjugal visit scheme for a year. While visitors are not stripped, they go through a metal detector.

Inmates Do Not Have All-time Privacy

The prison personnel carries out routine checks, during which everyone in the room comes out for count and search. Again, the officer may obstruct the visit when they need to administer medications as necessary.

Conjugal Visits FAQ

Are conjugal visits allowed in the federal prison system?

No, currently, extended family visits are recognized in only four states across the United States – Washington, New York, Connecticut, and California.

What are the eligibility criteria?

First, conjugal visits are only allowed in a medium or lesser-security correctional facility. While each state has unique rules, commonly, inmates apply for such visits. Prisoners with recent records of reoccurring infractions like swearing and fighting may be ineligible.

To qualify, inmates must undergo and pass screenings, as deemed appropriate by the prison authority. Again, for instance, California rules say only legally married prisoners’ requests are granted.

Are gay partners allowed for conjugal visits?

Yes, but it varies across states. California and New York allow same-sex partners on conjugal visits. However, couples must have proof of legal marriage.

Are conjugal visits only done in the US?

No, although the practice began in the US, Mississippi precisely, other countries have adopted similar practices. Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, and Canada, for example, are more lenient about extended family visits.

Brazil and Venezuela’s prison facilities, for example, allow weekly ‘rendezvous.’ In Columbia, such ‘visits’ are a routine, where as many as 3,500 women troop in weekly for intimacy with their spouses. However, Northern Ireland and Britain are entirely against any form of conjugal programs. Although Germany allows extended family visits, the protocols became unbearably tight after an inmate killed his supposed spouse during one of such visits in 2010.

Benefits of Conjugal Visits

Once a normal aspect of the prison system, conjugal visits and the moments that prisoners have with their families are now an indulgence to only a few prisoners in the system. Many prison officials cite huge costs and no indications of reduced recidivism rates among reasons for its prohibition.

Documentations , on the other hand, say conjugal visits dramatically curb recidivism and sexual assaults in prisons. As mentioned earlier, only four states allow conjugal visits. However, research shows that these social calls could prove beneficial to correctional services.

A review by social scientists at the Florida International University in 2012 concludes that conjugal visits have several advantages. One of such reveals that prisons that allowed conjugal visits had lower rape cases and sexual assaults than those where conjugal visits were proscribed. They deduced that sex crime in the prison system is a means of sexual gratification and not a crime of power. To reduce these offenses, they advocated for conjugal visitation across state systems.

Secondly, they determined that these visits serve as a means of continuity for couples with a spouse is in prison. Conjugal visits can strengthen family ties and improve marriage functionality since it helps to maintain the intimacy between husband and wife.

Also, it helps to induce positive attitudes in the inmates, aid the rehabilitation process, and enable the prisoner to function appropriately when reintroduced back to society. Similarly, they add that since it encourages the one-person-one partner practice, it’ll help decrease the spread of HIV. These FIU researchers recommend that more states should allow conjugal visits.

Another study by Yale students in 2012 corroborated the findings of the FIU researchers, and the research suggests that conjugal visits decrease sexual violence in prisons and induces ethical conduct in inmates who desire to spend time with their families.

Expectedly, those allowed to enjoy extended family visits are a lot happier. Besides, they tend to maintain the best behaviors within the facility so that they don’t ruin their chances of the next meeting.

Also, according to experts, visitations can drop the rate of repeat prisoners, thus making the prison system cost-effective for state administrators. An academic with the UCLA explained that if prisoners continue to keep in touch with their families, they live daily with the knowledge that life exists outside the prison walls, and they can look forward to it. Therefore, these family ties keep them in line with society’s laws. It can be viewed as a law-breaking deterrence initiative.

For emphasis, conjugal visits, better termed extended family visits, are more than for sex, as it seems. It’s about maintaining family ties, primarily. The fact is, away from the movies, spouse-alone visits are surprisingly low, if at all allowed by most states’ regulations. Extended family visits create healthy relationships between prisoners and the world outside the bars. It builds a healthy start-point for an effective reentry process, helping inmates feel hope for a good life outside jail .

Harassment and Cyberbullying as Crimes

What is a bench trial jury trial vs. bench trial, related articles.

History of the Freedom of Information Act

Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

Tort Law Definition & Examples

Bail vs Bond: What’s the Difference?

Sex, Love, & Marriage Behind Bars

What are conjugal visits really like? Incarcerated journalist John J. Lennon takes Esquire inside one of the last bastions of prisoner intimacy in America: trailers of New York.

I first heard about the trailers, prison vernacular for conjugal visits, on Rikers Island. It was 2002, I was twenty-four, and I was awaiting trial on murder charges. The guy the next bunk over in the communal dorm knew I was facing a lot of time, even if I didn’t know that. I was delusional in the beginning. We all are.

The bunkmate had just finished a dime—a ten-year sentence—for assault and was now in on a parole violation for breaking curfew, caught on a tip called in by his wife. Still, he loved her, and he loved telling me about going on conjugals with her up in Auburn, a maximum-security prison. It wasn’t just about the sex, he said. It was forty-eight hours of freedom, or close to it. Most of New York’s maximum-security prisons had them. They weren’t trailers, not anymore, but modular homes. He described the units: two, sometimes three bedrooms—the prison supplied pillows, bed linens, towels, and washcloths—a living room, a bathroom, and a full kitchen stocked with pots and pans, a coffee maker, a blender, and utensils. A wire bolted to the counter next to the sink was connected to the handle of the kitchen knife. His wife would bring clothes, cosmetics, and groceries: milk, eggs, pork chops, shelled shrimp. Glass containers weren’t allowed; neither was alcohol, not even as a makeup ingredient. Outside there was a picnic table, a barbecue pit, and a children’s play area.

It was, the fella in the next bunk told me, an opportunity for good times, good eating, and good sex. An incentive to stay out of trouble in the hope of experiencing a touch of love.

There was a hitch: Your partner had to be your legal spouse. Close family members were also eligible, of course, and this was really the objective of these visits: to build and maintain better family ties. But that was beside my bunkmate’s point. If I was convicted, he said, he recommended I put an ad on one of those prisoner dating websites (Prison Pen Pals, Write a Prisoner), find a woman, fall in love, make it official, then head for the trailers.

In 2004, I was sentenced to twenty-eight years to life. The minimum was longer than I’d been alive. Early on, I didn’t think much about the implications for my love life. At twenty-four, I’d had plenty of sex but never a real relationship, or even healthy intimacy. Besides, there were more pressing concerns: appealing my conviction, learning how to survive in this place.

I first saw the trailers at Clinton Correctional, a maximum-security prison a few miles south of the Canadian border, in Dannemora. By then I’d learned that New York’s Department of Corrections and Community Supervision didn’t actually call them conjugal visits. Only Mississippi did. While the word conjugal simply means “related to marriage,” these visits began to carry lewd implications, and other states opted to rebrand: In California, it was known as “family visiting.” In Connecticut and Washington, they were referred to as “extended family visits.” In New York, it was, and still is, called the Family Reunion Program, or FRP.

In 2005, I had my first FRP visit—with my mother and my aunt. My aunt cooked bacon and eggs in the morning, grilled porterhouse steaks and tossed salads for dinner. We sank into the soft couches, ate, and watched Law & Order reruns, oddly Mom’s favorite show. We talked until interrupted by the muffled screams of a couple through the wall of the attached unit. We laughed awkwardly, avoiding eye contact, and I felt kind of jealous. Three times a day, a phone in the unit rang. I picked up, spat my last name and identification number into the receiver, then stepped outside and waved to the watchtower guard. That count was one of the only reminders of prison.

When I returned to my block, guys asked how the conjugal had gone. Great, I said. When I mentioned it was with my mother and my aunt, they sort of nodded, like, Oh, that’s cool, too. I loved visiting with my family. But I did start to think about what it would be like to be with a woman again.

.css-f6drgc:before{margin:-0.99rem auto 0 -1.33rem;left:50%;width:2.1875rem;border:0.3125rem solid #FF3A30;height:2.1875rem;content:'';display:block;position:absolute;border-radius:100%;} .css-1aglugu{font-family:Lausanne,Lausanne-fallback,Lausanne-roboto,Lausanne-local,Arial,sans-serif;font-size:1.625rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-1aglugu{font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1.2;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1aglugu{font-size:2.375rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-1aglugu b,.css-1aglugu strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-1aglugu em,.css-1aglugu i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;}.css-1aglugu:before{content:'"';display:block;padding:0.3125rem 0.875rem 0 0;font-size:3.5rem;line-height:0.8;font-style:italic;font-family:Lausanne,Lausanne-fallback,Lausanne-styleitalic-roboto,Lausanne-styleitalic-local,Arial,sans-serif;} Trailer visits were never perfect. Sometimes they were hard. But in many ways, they felt like rehearsals for life on the outside.

I got by with my hand and my memories, with the occasional assist from Buttman or High Society. Many of us who’ve been locked up all these years try idiosyncratic methods to pleasure ourselves. Some use a Fifi—a rolled towel with a plastic bag stuffed in the crevice; inside the bag is a rubber glove lubed with Vaseline that can be warmed in a hot pot of water, if one prefers. The crevice can be tightened or loosened by a strap wrapped around the rolled towel, creating different sensations. Fucking Fifis was an intimate ritual for one of my neighbors. At night he hung a curtain across his cell bars, prepped his Fifi, rolled the whole thing up in his mattress—he said it was more like a big-booty girl that way—laid out a few porno mags, and started thrusting.

But I wasn’t looking to hump a Fifi for the next twenty-five years.

Married men in the joint who went on conjugals seemed to have the most meaningful lives: They worked out, they went on visits, they sported crispy new sneakers and polo shirts with the horse, as if to say to the rest of us, I got a lady who loves me, and I got more status than you. At least, that’s how I took it. Every few months, they disappeared—most men kept their conjugal dates to themselves to avoid attracting envy—but we all knew where they’d gone. They came back to the cellblock with hickey-covered necks, looking pleasantly tired. I decided that was how I wanted to serve my sentence.

Mississippi State Penitentiary, of all places, was the first facility in the U. S. to offer conjugal visits, in the early 1900s. Also known as Parchman Farm, the segregated prison functioned as a revenue-generating plantation that produced cotton, cattle, pork, and more; its prisoners performed all the hard labor. To incentivize their work, administrators began arranging for prostitutes to visit on Sundays, and prisoners slept with them wherever they could—tool sheds, storage areas, the barracks. At first, only Black prisoners were allowed to participate, and for deeply racist notions “about Black men’s allegedly voracious sexual natures and appetites,” says Heather Ann Thompson, author of the Pulitzer-prize-winning history of the Attica uprising, Blood in the Water, “that Black prisoners could be forced to work even harder not just under threat of the lash but also, due to their savage nature, the promise of sex.”

Starting around 1940, all of Parchman’s prisoners were able to participate, regardless of race. By the late fifties, prostitutes were banned, replaced by prisoners’ spouses, common-law wives, and female friends. In 1972, the program opened to the facility’s female prisoners. Still, the system was marked by prejudice. “The most important question concerning a program of conjugal visiting,” wrote Columbus Hopper in his 1969 study of Parchman, Sex in Prison, “is whether it helps to reduce the problem of homosexuality in prison.” Hopper was the leading conjugals researcher of his time, and the “problem of homosexuality” seems to have been one of the main forces behind his advocacy. Truth is, in my twenty-one years of incarceration, I’ve never been sexually assaulted or witnessed that kind of assault.

New York’s first FRP began in 1976, with five 12-foot-by-70-foot trailers in a former cow pasture at Wallkill Correctional. Attica got its trailers in 1977, six years after the prisoner uprising for more humane treatment that, when law enforcement took back the prison, left thirty-nine dead. In the first eighteen months of Attica’s FRP, 1,179 prisoners participated.

By 1993, seventeen states allowed some version of extended family visits. That year in New York, 12,401 family members attended FRPs across the state. “The effectiveness of the program is beyond dispute,” the prison commissioner wrote in an op-ed around that time.

Data supports the former commissioner’s claims. According to a recent literature review, prisons that allow conjugal visits have better disciplinary records than those that do not. What’s more, studies have determined that released prisoners with an established relationship have a much better chance of not returning to prison. (In 1980, New York’s corrections department published findings suggesting that participation in the program decreased recidivism rates by as much as 67 percent.)

Yet since the start of such programs, fierce resistance has followed. By the early nineties, the era of mass incarceration was fully under way, and across the country, prison programs that incentivized good behavior—furloughs, work release, college, conjugals—were on the chopping block. Why, the thinking went, should we coddle criminals with taxpayer money? (It’s worth noting that FRP upkeep is paid for in part by prisoner fundraisers.) And don’t conjugals present one more way to introduce contraband?

As early as 1969, when Hopper published his findings on Parchman, conjugal visits were available in Chile, Ecuador, Japan, Mexico, Costa Rica, and the Philippines. Today, that list includes Qatar, Argentina, Brazil, Belgium, Sweden, Spain, France, Russia, and Saudi Arabia.

The United States has shifted in the opposite direction. In the eyes of the law, conjugal visits are a privilege, not a right. The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld prison administrators’ latitude to limit prisoners’ rights, including visitation, writing in 2003 that “freedom of association is among the rights least compatible with incarceration.” In 2014, Mississippi did away with its program. “There are costs associated with the staff’s time,” the state’s prison commissioner said at the time. “Then, even though we provide contraception, we have no idea how many women are getting pregnant only for the child to be raised by one parent”—as if such family planning were his call to make.

Today, only four states allow conjugal visits—New York, California, Washington, and Connecticut—though when Covid came, Connecticut’s program was suspended, and it has yet to return. Federal prisons don’t offer the privilege. New York’s program has been a success: FRP is offered at twelve of its fifteen maximum-security prisons and eleven of its twenty-six medium-security prisons. Since 2011, same-sex couples have been able to participate. Yet each year over the past decade or so, Republican state senators have introduced a bill to eliminate FRP. Conservatives preach the importance of a solid family structure. Why would they want to sabotage prisoners who are trying to build and maintain theirs?

By 2009, I was in Attica; my appeals had been denied. I was thirty-two and lonely. I’d spend hours each day watching the tiny TV in my cell. The Bachelor was my favorite show—a glimpse of intimacy, however stage-managed, and a break from my bleak reality. I felt like I was squandering an opportunity by not putting myself out there. I told Mom what the guy on Rikers Island had suggested, and she put an ad on the prison dating website Friends Beyond the Wall.

Danielly was a year younger than me and lived with her teenage son in a housing project on the Lower East Side. “I’m Dominican, and brown. Do you like that?” she wrote. Yes, yes, I loved it! In an early letter, I brought up the trailers, told her to imagine an uninterrupted weekend together in a sort of cabin, no cell phones, no distractions—just us. She didn’t need to be sold. Her mom had married a guy who’d done time, she told me, and she remembered visiting those little homes in the prison as a young girl.

Danielly started visiting me at Attica. She was my type—curvy, full of attitude and affection. We had the kind of chemistry that made my stomach flutter. But I soon learned that my type was much harder to handle on the inside than it had been when I was on the outside. The guy she’d described as her ex-boyfriend was more like her current boyfriend. When I called her, she sometimes wouldn’t answer. I was left lovesick, and that’s no way to live in prison. So I let her go.

In January 2011, I started corresponding with Raina, a California blonde, thirty-nine, who’d never been married and had no kids, and it wasn’t a dealbreaker that I’d killed a man. She had a great sense of humor, and while she’d known darkness in her own life, she’d needle anyone who took theirs too seriously. I was hooked. She was emotionally intelligent, we spoke the language of recovery, and our relationship felt safe. She moved across the country for me. One day in 2012, in Attica’s visiting room, I proposed to her, and she said yes. Six months later, we joined a few other couples in a small room with a Goofy mural painted on the wall and Attica’s town clerk seated at a table, and we got married.

By 2014—after a series of applications, denials, appeals, and interviews, including one in which Raina was told I didn’t carry any sexually transmitted diseases—we had our first FRP date.

Two days beforehand, I had to piss in a cup under a guard’s gaze for my drug screen. Then again the day of, and again after I came off the trailer. Most of the work was on Raina: shopping, traveling, then getting processed, food pushed through an X-ray machine, gloved fingers sifting through her panties and K-Y jelly.

The corrections officer escorted a handful of us through the Attica lobby, a part of the prison I had never seen before. Gates opened and closed, and we walked to the FRP compound. A fence enclosed the five red-sided homes, situated so that the rest of the prison couldn’t see in. Though the watchtower guard kept a close eye.

Sitting on the couch, looking around, I felt . . . joy. In the system, you’re always waiting, and never for anything good: trial, sentencing, transfers, getting cuffed and shackled, always in a cell or a bullpen or on a bus eating bologna sandwiches. Now I didn’t know what to do with myself, and I loved it. I got up from the couch, turned on the stereo, then walked outside on the grass, sat on the children’s swing, went back inside. I grabbed the remote, turned on the flat-screen television, flipped through the stations. To do whatever I wanted, and to be waiting for my wife so we could do whatever we wanted—I felt giddy. Through the window I watched my neighbor in his kitchen as he boiled the silverware—forks, (butter) knives, a spatula, a ladle, all metal and engraved with tracking numbers—in one pot of water, and added a few drops of scented oil to another, to perfume the place. Finally, I heard one of the guys yell, “They’re here!”

A corrections van with blue-tinted windows pulled up, and the family members got out. A little boy ran to his father and jumped in his arms. And there was Raina. The CO let me help her with her luggage, which was in a container marked with our unit number.

As soon as the door of our unit closed, we threw the groceries—including cuts of filet mignon and A.1. sauce—on the table and started awkwardly kissing. As we began to undress, there was a knock on the door. Raina put on a shirt and I cracked the door. It was the CO, who just needed our container. It was like that, the conjugals; they were such a departure from regular prison life. Even the staff interactions were all good.

Raina and I got back to it. It was my first time in eleven years, so I figured I’d finish fast. But it was the opposite. We went at it for a while—soft, hard, slow, fast, this way, that way—and nothing seemed to bring either of us closer to climax. It was like I’d never touched a woman before. It felt weird that nobody else was watching us. I eventually pulled out and brought myself to ejaculation.

On some level, we hadn’t expected the first time to be amazing. Though it’s hard to make bad sex better, we had to try. We loved each other. We went on six more FRP visits, but the situation didn’t improve. Our issues were less about friction and more about fantasy, or the lack thereof.

Danielly had sent me letters over the years since we’d first met, none of which I’d replied to. But in 2015, as my relationship with Raina was coming to an end, I finally wrote back, explaining my marital woes. Danielly replied that I never should have gotten married in the first place, that she was my soulmate. She said she was still on and off with her boyfriend, but he didn’t matter. If I got divorced and married her instead, she’d come to Attica and fulfill all my fantasies.

I divorced Raina and proposed to Danielly.

In October, we got married by the same Attica town clerk who’d officiated the last time. The Goofy mural was gone. We posed for our wedding picture in front of a seascape of sea lions and colorful fish. Danielly looks sad in the photo, barely smiling. She’d wanted this day to be so much more special than it was.

Afterward, I bribed a CO with a few packs of Newports to let the cellblock’s tattoo artist come into my cell, and with a needle made from an uncoiled lighter spring powered by a repurposed beard-trimmer motor, he inked danielly on the inside of my upper arm in looping script. Once she ditched the boyfriend for good, she had my name inked on her forearm. We craved each other. Our kisses, deep and long and wet, always felt like good sex.

I wanted to transfer to Sing Sing, forty miles north of New York City—among other reasons, it would take Danielly an hour by train, as opposed to the eleven-hour bus trip she took both ways to visit me at Attica. But Attica was a disciplinary prison, rife with violence; the number of prisoners on good behavior was low, the FRP waitlist short. You could book a spot every forty or fifty days. At Sing Sing, the wait was closer to ninety days. I weighed the pros and cons. Con: waiting twice as long to be together. Pro: saving Danielly the hassle of a big trip to the middle of nowhere, which would probably mean I’d see her more often.

I submitted my paperwork, got approved, and transferred in November 2016.

In February, we had our first FRP date. The compound was pretty much the same as the one at Attica, but at Sing Sing we got a Polaroid camera and twelve blank photos. Some couples went into the units and did not come out for the allotted forty-eight hours. Others were more social. Me and my friend Andy Gargiulo—convicted in 2006 of killing his reputed mobster brother-in-law; we’d had the same lawyer—would sometimes coordinate our FRP visits. He was a lot older than me, around eighty, but we got along. So did our better halves. His wife brought the best Italian food in Brooklyn—cannolis, fresh mozzarella, and tender veal—and when the weather was nice, the four of us would sit outside and barbecue.

Danielly was provocative, and that turned me on. We argued; we canceled visits on each other. We often had angry, shit-talking sex. Sometimes we played nice, but she’d never let it get to my head. “Boy,” she’d say, “you have so much to learn about women.” We couldn’t have sex for the entire forty-eight hours, but it sometimes felt like we were trying.

Intimacy came in other forms. She introduced me to ASMR; I brewed Bustelo for her and microwaved the half-and-half so it wouldn’t cool off the coffee too much. “Coffee,” by Miguel, became our song. We watched The Notebook, and she recited her favorite lines. We watched Warrior, and when Tom Hardy’s character hugs his drunk father, played by Nick Nolte, Danielly comforted me as I cried.

I know now that our relationship wasn’t healthy. My moments of joy were outweighed by my jealousy and anxiety. I’d get annoyed if she didn’t read my latest article. “You’re all into yourself and your career,” she’d say. “Women don’t like that, bro!” Or “I fell in love with the guy at Attica, before he became the writer.” That one hurt. But it’s not like I’d ask about her job as a nurse at a Bronx clinic. She’d want to talk about our future, and I’d urge her to stay in the present. She’d storm off into the bedroom, slam the door, and curse me out in rapid-fire Spanish. Well, I’d think, this is life.

By March 2020, our relationship was rocky. But for the first twenty-four hours of our first FRP in more than a year, we were getting along. As we prepped lunch, a knock came at the door. It was the security captain. Because of Covid, our visit was over, along with our last shot at rekindling.

By the time FRP visits were restored, a year and a half later, I’d been transferred to Sullivan Correctional, in the southern Catskills. Danielly came up twice. But too much time had passed, and other relationships had formed: hers with somebody else, mine with my career. Becoming a journalist in the joint brought its own stress, and my anxiety worsened; things like pissing in a cup with a guard peeking seemed impossible. Recently, we divorced.

Would I have been better off not having experienced intimacy for the past twenty-one years? Would Raina and Danielly have been better off never having met me? I’ve since realized that in both relationships, I focused more on the affection I was getting than the affection I was giving. All this time spent living in my head, confined to a six-foot-by-nine-foot cell, has rendered me less expressive and more emotionally stuck. My thoughts would bounce around my brain but never make it out of my mouth, which left Raina, then Danielly, feeling neglected. The time I used to spend writing love letters I now spend writing articles. Sometimes I feel like I took the two of them for granted. There’s an immense effort, this leap toward love in which the only physical manifestation comes in the form of conjugal visits. And it’s exerted not by the prisoners but by our partners. They wait, they shop, they lug, they travel, they get gossiped about by friends and family and insulted by COs.

Trailer visits were never perfect. Sometimes they were hard, especially at the end—me returning to prison, my woman going home alone. But in many ways, they felt like rehearsals for life on the outside. I believe that because of my experiences with conjugals, when I do get out, I’ll be more sensitive to the feelings of those closest to me. “It remains utterly and inescapably true that to be a human being is to need to be connected to, to bond with, and to be nurtured by other human beings,” Heather Ann Thompson told me. “Serving one’s sentence does not change that.”

So I’m single now. Middle-aged, too. Sometimes I imagine the kind of woman I’ll attract when I’m on the outside, and I wonder if I’ll resent her because she didn’t fall for me when I was on the inside. Which is absurd, and I know I need to work that shit out. But it also feels like a nod to the women who’ve loved me, a thank-you to all the partners who’ve sacrificed so much to share their love with those of us who are locked up.

I think about a moment Danielly and I shared with Andy and his wife, who was wearing Prada glasses and a perfume called La Vie Est Belle. The sun was bright; we sat at the picnic table, eating the best of both kitchens. Andy was talking about a TV show he watched in his cell—maybe it was America’s Got Talent —and Danielly told him how she also loved that show. While recalling the final performance of a child singer who’d recently won, Andy choked up. Right there at the wooden table, surrounded by the thirty-foot concrete wall and the guard with the AR-15 perched in the tower. Danielly teared up, too. “He gets emotional on these visits,” Andy’s wife said in a tough Brooklyn accent, smiling. More than the sex, it’s moments like these—simple, safe, and endearing—that have provided me with what prison has stripped away: a taste of intimacy.

@media(max-width: 73.75rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.4375rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.5625rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}} Esquire Select Exclusives

What Really Happened to Baby Christina?

Inside My Mid-Life Crisis

In the War Room with Steve Bannon

There Are Only Two Options Left In Ukraine

I Got Paid For Two Years and Never Did Any Work

I Got Paid to Spy on People While They Worked

God, Magic Mushroom, and Me

The Prisoner and the Pen

The Accidental Activist

I’m Losing Weight by Secretly Taking Wegovy

The Scout Who Found Patrick Mahomes

- Vista DUI Attorney

- DMV Hearings

- DUI Defenses

- Domestic Violence

- Sex Crime Defense

- Child Molestation

- Child Pornography

- Hit and Run Accident

- No-License Driving

- Reckless Driving

- Juvenile Crime

- The Three Strikes Law

- Weapons Charges

- Theft Defense

- Fraud Charges

- Drug Offenses

- San Diego Office

- The Criminal Process

- Criminal Defense FAQ

- Hiring a Criminal Lawyer

- Vista Criminal Law Blog

- Contact Us 24/7

Conjugal Visits Are Real and They’re Great for Society

May 28, 2021 Written by Jill Harness and Edited by Peter Liss

Conjugal visits are regularly referenced in movies and TV shows but they almost seem unreal. After all, why should people serving time for crimes be allowed to have sex when they’re supposed to be punished? But that’s one of the big misconceptions about what the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation calls “Family Visits.” The official name isn’t just bureaucratic code for conjugal visits -the real reason the state allows these visits is to provide inmates to stay close to their families. And studies show this kind of visitation program has some profound benefits.

How did Conjugal Visits Get Started?

Conjugal visits were originally introduced in Mississippi state in the early 1900s. At the time, inmates were essentially just used as slaves, even physically beaten if they broke the rules or failed to work hard enough. To provide positive encouragement for those who worked hard and followed the rules, the prison brought prostitutes for the best inmates every Sunday. Eventually, the prison started allowing prisoners’ wives and girlfriends to visit as well.

The idea eventually caught on, and over the years, many other states adopted the idea of letting wives spend time with their inmate husbands, with over 1/3 of states in the United States eventually enacting some type of conjugal visit program. Unfortunately, with the push to “get tough on crime” that took place in the 90s, many states got rid of these types of programs, which were seen as “being soft on crime” by giving prisoners “sex visits” when they should be being punished. Nowadays, the only four states that offer conjugal visits are California, Connecticut, New York and Washington.

What is a Conjugal Visit?

A conjugal visit is where an inmate gets to see their family with some slight level of privacy and intimacy. One of the big misconceptions about these visits is that they are purely designed to allow prisoners to have sex. While that may be how the program started and may be part of the experience for married couples, the true purpose of the visits is to allow prisoners the opportunity to spend time with their families. Notably, in New York, where inmates are allowed to visit with extended family members, only 48% of these meetings were with a spouse.

Even when the visit is with a spouse, most inmates say that while the chance to have sex with their partners was nice, the family visit was more about being intimate with the person they love for anywhere from 30 to 40 hours. Considering that standard prison visits require all conversations be monitored by guards, and partners are only permitted to kiss at the start and end of the visit, the chance to have private discussions for 24 hours and spend the night in bed together is a welcome change.

How do the Visits Work?

Inmates who qualify for family visits can spend up to 40 hours in an apartment located on prison grounds with their spouses, domestic partners, or other immediate family members, including children, siblings or parents. These apartments are equipped with toiletries, sheets and condoms.

Prisoners are allowed no more than four visits per year. Unfortunately, because of the program’s popularity and the limited number of prison apartment spaces, it’s more likely prisoners will only be able to participate twice a year.

Not all prisoners are eligible for the program. Anyone on death row, who is serving a life sentence, or who was convicted of a sex offense is ineligible. Additionally, inmates must have a record of good behavior, and anyone on disciplinary restrictions cannot participate. Those eligible must apply through their correctional counselor.

Visiting family members will not be strip-searched, though the prisoner will. While the visit is mostly unsupervised, the area will be searched as often as every four hours.

Visitors must follow many rules , including what they wear. For example, no one can wear blue jeans, and women cannot wear short dresses, short skirts, strapless tops or form-fitting clothing.

Why do States Allow for Family Visits?

There are many benefits, but the biggest one is a dramatic reduction in recidivism rates . One study in New Mexico (which recently discontinued conjugal visits) showed that prisoners who participated in extended family visits had 70% less chance of ending up in prison than those who did not participate.

Family visits are, therefore, more effective than education in keeping former felons out of prison. The effectiveness of these programs makes sense, considering they help maintain relationships between inmates and their loved ones. These relationships are critical in helping convicts readjust to life outside prison after release.

Though many people consider these programs to be a waste of taxpayer money, it’s been shown that every $1 spent on education in prisons saves taxpayers $5 annually due to the reduced cost of housing prisoners. Given that visits with family members cost less and are even more effective at reducing crime rates, maintaining these programs seems to be a no-brainer.

Reducing recidivism rates is not the only benefit of conjugal visits. By encouraging prisoners to be good to earn time with their loved ones, prisons can reduce violence and dangers to other inmates and guards -which could further reduce the tax rates associated with incarceration. More savings can be realized as well, because the more prisoners are model citizens, the more likely they are to be eligible for early release programs, where they can enjoy a complete family reunion outside of the prison.

There is also evidence that conjugal visits reduce prison rape . One study found that sexual violence in prison occurred at a rate of 226 per 100,000 prisoners in states without these programs while occurring at a rate of 57 per 100.000 prisoners in states with family visits.

Conjugal Visits During Covid-19

Unsurprisingly, these programs were temporarily discontinued as a result of the ongoing pandemic, but they have since been reinstated. To participate in visits , all guests over 2 must be vaccinated or show proof of a negative covid test taken within 72 and 96 hours of the visit. Following the visit, inmates must take a covid test within 72 and 96 hours. Those who test positive, are unvaccinated, or refuse to take the test will be placed in quarantine after the visit.

Alternative Sentences are Still Preferable

Of course, being allowed to continue living with your family is better than any conjugal visit. Maintaining your family life is possible if you prove your innocence or are given an alternative sentence such as probation. Your choice of criminal lawyer makes such a drastic difference in the outcome of your case. If you have been accused of any crime, please call (760) 643-4050 to schedule a free initial consultation with Peter M. Liss.

- DUI / Felony DUI

- Driving Offenses

- White Collar Crimes

- Violent Crimes

- Sex Offenses

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Attorney Peter M. Liss, (760) 643-4050 380 S Melrose Drive #301 Vista, CA 92081

Copyright 2003, 2021 Peter M. Liss, Esq. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

About the Legal Information on This Website

I rely on my experience as a top defense lawyer in my area to personally review all information on this site; however the information offered here should not substitute as legal advice. If you have been arrested or charged with a crime in Vista, please contact a qualified defense attorney.

This is a placeholder for your sticky navigation bar. It should not be visible.

One Conjugal Visit

By nancy mullane.

How long could your relationship last without a kiss? Without more than a kiss? Could you last a year? Two? What about ten? Twenty? In prison, couples are forced to keep their relationships alive in visiting rooms, with 2 second hugs. One two. Let go. So they write letters and make phone calls. Many break up.

But there’s another option. If you’re married or in a domestic partnership, you might be eligible for something called a family visit, also known as a conjugal visit, or on the inside, a booty call. It means a couple can be together, inside prison, alone or with their children for extended visits. They can have privacy and they can have sex.

Back in the 90’s, 17 states allowed prisoners to have these conjugal visits. But things have changed. Earlier this year, Mississippi and New Mexico both ended conjugal visits in their prisons and today only three states, New York, Washington and California allow inmates to have this kind of intimacy.

I’m standing with Myesha Paul at the gate at San Quentin, the prison just north of San Francisco. Because her husband, Marcello Paul is locked up in a California prison, they still qualify for a conjugal visit and she’s letting me tag along.

Myesha is middle aged with short, bleached blond hair and a no-nonsense look in her eye. She’s wearing baggy red sweatpants and a sweatshirt that’s too big. She knows the spoken and unspoken rules to one of these visits. The officers guarding the prison have told another woman who’s come for a visit she has to go back to her car and change before she’ll be allowed inside.

“Her t-shirt is fitting real tight, so yeah, they’re gonna make her change all that,” Myesha says watching the woman walk away. “You go through a lot comin’ up her. It got to the point where I just come up in sweat pants. Baggy sweat pants. Too much of a hassle. I’m not puttin’ on anybody else’s clothes. Leggings are comfortable but they’re not for up in here.”

“Why not,” I ask.

“They’re a little too revealing. They don’t want you to have anything that’s form fitting and although we come with hips and all that, so it’s kinda hard to find that don’t fit around, you know?” Myesha laughs, looking down at her full body. “I just buy some men’s sweat pants and make it work.”

“So when you’re inside, do you bring different clothes to wear for when you’re alone?” I ask.

“Mostly just shorts or comfortable pajamas,” Myesha says. “I don’t usually get dressed.”

Even in California not all prisoners qualify for these intimate visits. Prisoners convicted of a sexual crime or a violent crime against a minor or a member of their family and those serving life sentences are denied conjugal visits. Except for what happens behind closed doors during these officially sanctioned private visits, sex is totally illegal in prison. That means tens of thousands men and women locked up in prisons throughout in America may never be able to sleep next to their partner or have sex, ever again.

As Myesha waits outside the gate, I ask her to describe the process for going inside the prison for a conjugal visit. Looking at the door stamped VISITOR, Myesha says, “I’m waiting for the family visit coordinator to come. (Officer) Foster. He’ll come and he’ll take me in there,” she says looking past the door into a space where officers will check her belongings. “He’ll get my bags and go through them instead of the metal detector. Then I go through the metal detector. I also go inside and pick out some movies, dominoes, that type of thing. Then he’ll grab my stuff, put it in the trunk, and take me down to see my husband.”

Watching Myesha pass through security, I imagine this prison approved sex will happen someplace prison-like, in a tiny room with a bare mattress. They’ll give them an hour.

Turns out, it’s not like that at all.

After passing through a metal detector Officer Foster helps Myesha carry her duffle bag and personal things to the car. It’s his job to escort the previous visitor out, and turn right back around and drive Myesha, in. One in, one out.

It’s a long drive around the edge of the prison, through a big gated checkpoint and up to a small one-story building surrounded by chain-link fence that’s topped with razor wire. An officer looks down from a watchtower nearby.

Marcello Paul, a big man with dreadlocks, gold capped teeth and a beaming smile walks to the opposite side of the locked gate and waits.

When it’s opened, Marcello and Myesha give each other a quick hug, and help carry the bags and pre-ordered food into the apartment.

While Myesha puts the food into the refrigerator, Marcello gives me a tour of the two-bedroom apartment.

There are cabinets with dishes, cups, bowls and plates, a microwave, sink and stove. There’s a table where Marcello says they say grace and play games. In the living room is a puffy black couch and chair. Marcello says it’s black leather. It’s not really leather, but it’s nice.

There are two bedrooms. The first has a worn double mattress on a metal frame. Marcello says he does a pre-clean to make sure everything is intact and washed, and then two days later, when it’s time to go, he cleans everything again, so it’s just the same as when they came in.

Turning from the first bedroom, is a bathroom with a door on it. That’s no small thing inside prison where toilets are public.

Looking into the spare room, a portable baby crib leans against the wall. Some couples bring their children along on a family visit. Myseha and Marcello don’t have any shared children so they spend their weekends alone.

In the middle of the room is a double bed, metal springs sticking out the edge of the mattress. But it’s the large round wet spot in the middle of the mattress we’re both looking at. Marcello says he’ll turn the mattress over and lay down a lot of blankets on top of the mattress.

Standing with Marcello, looking around, if it weren’t for the two officers standing in the middle of the room, it’d seem like a pretty normal apartment.

The officer tells me it’s time to go. Marcello and Myesha get just 48 hours together in the apartment. Once a month.

Myesha says they’ve been together 14 years. They met and fell in love while Myesha, a home health care worker, was taking care of Marcello’s mom. Marcello had committed a robbery before they met and gotten away with it. But eventually, it caught up with him and he was sentenced to 10 years. He’s done five of them.

I think about them all weekend.

Monday morning, I go back and meet up with Myesha as she’s coming out. We sit in her car and talk. She says the weekend with Marcello, “was good. It’s always good. Just don’t like going home.”

“Why?” I ask.

“I’m leaving my husband behind,” Myesha says. “We sat outside and played dominoes on Saturday. After that we went in and watched TV, watched movies.” She says they started with The Wire.

She tells me they pulled the bed into the living room so they could lie together while they watched. They cooked burgers and tacos. They listened to music. And sure, she says, they had sex. I ask if they ever have a conjugal visit when they don’t have sex. Myesha pauses, then says, “No. I mean we might have a conjugal visit where we don’t have as much sex as the one before. But no.”

But she says, for her a conjugal visit really isn’t about the sex. It’s about the smaller, quieter things, like Marcello waking her up in the morning, “It feels good,” she says, “because I don’t get that at home. Ya know. At home I’m sleeping by myself, unless my grandbaby or one of my kids wanna sleep with me. But they’re grown. But they still do sleep with me sometimes. But other than that, ya know, I’m waking myself up in the morning, or the alarm clock is waking me up, or my grandson comes and wakes me up. It’s good to have my husband waking me up.

“It’s the nicest thing about being married,” I say, “isn’t it? Waking up?”

“Yeah,” Myesha says, “Together.”

“Not alone,” I say, “You look up and there’s that person.”

“Yeah. I think he watches me through the night,” Myesha says, “ I know he do cause sometimes I wake up and he’s looking at me. And I do the same to him. Sometimes he’s sleeping and he wakes up and I’m watching him.”

While we’re sitting in her car, talking, her cell phone rings. It’s Marcello calling to make sure Myesha gets home safe.

Even though conjugal visits aren’t allowed in most US prisons, in many countries they’re common. Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Russia, Spain, and Saudi Arabia all allow inmates and their partners to have conjugal visits. Mexico considers them a universal privilege and even allows families to move into prisons and live with their imprisoned relative.

All photos courtesy Nancy Mullane.

Edited By: Sally Herships

Produced By: Kaitlin Prest

Advisory Panel Scholar: Hadar Aviram

Music Composed by: Lawrence English

- Categories: Courts ,

- Criminal Justice ,

- Human Rights ,

- Personal/Family

- Tagged As: can i have sex in prison , conjugal visit , conjugal visits , episodes and events , families in prison , family and the law , family law , family visits , Get on the Bus , Inside San Quentin , Kaitlin Prest , life of the law , Nancy Mullane , prison , prison and family , Sally Herships , San Quentin , San Quentin State Prison , sex , sex in prison , visitation

Subscribe to Life of the Law

Sign up for newsletter.

Connect with Life of the Law – Send us your story ideas and comments. Thanks!

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

As Conjugal Visits Fade, a Lifeline to Inmates’ Spouses Is Lost

By Kim Severson

- Jan. 12, 2014

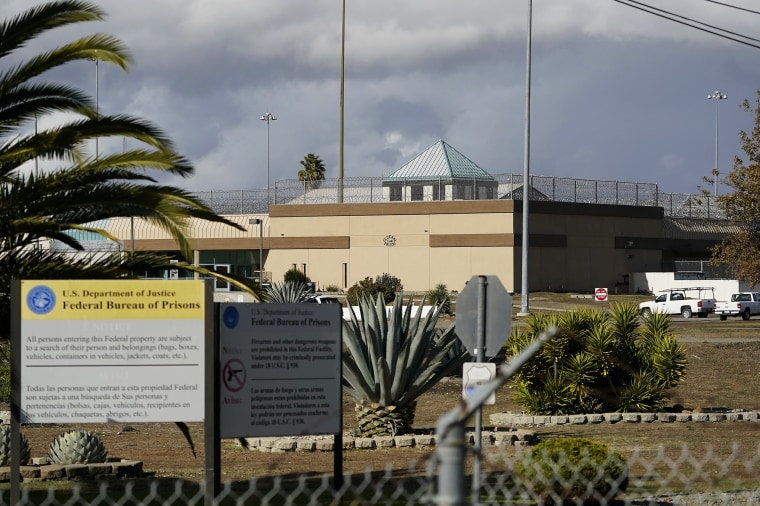

PARCHMAN, Miss. — To spend time alone with the man she married four months ago, Ebony Fisher, 25, drives nearly three hours through the flat cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta until she pulls into a gravel lot next to the state’s rural penitentiary.

She joins her husband, who in 2008 began serving a 60-year sentence for rape, aggravated assault and arson, in a small room with a metal bunk and a bathroom. For an hour, they get to act like a married couple.

“That little 60 minutes isn’t a lot of time, but I appreciate it because we can just talk and hold each other and be with each other,” said Ms. Fisher, who is studying to be a surgical assistant.

But conjugal visits, a concept that started here at the Mississippi State Penitentiary as a prisoner-control practice in the days of Jim Crow, will soon be over. Christopher B. Epps, the prison commissioner, plans to end the program Feb. 1, citing budgetary reasons and “the number of babies being born possibly as a result.” In Mississippi, where more than 22,000 prisoners are incarcerated — the second-highest rate in the nation — 155 inmates participated last year.

Since they began here in the early 1900s, when the penitentiary was just called Parchman Farm, conjugal visits have been an unlikely barometer of racial mores and changing times both in Mississippi and in states like California and New York, where married same-sex couples can participate.

In the 1970s, new prisons often included special housing for what had come to be called extended family visits. But by 1993, only 17 states allowed conjugal visits. Mississippi is one of just five that have active programs.

In California and New York, they are called family visits and are designed to help keep families together in an environment that approximates home. Some research shows that they can help prisoners better integrate back into the mainstream after their release.

Visits in those states, and in Washington and New Mexico, can last 24 hours to three days. They are spent in small apartments or trailers, often with children and grandparents, largely left alone by prison guards. Visitors bring their own food and sometimes have a barbecue.

In New York, about 8,000 family visits were arranged last year, a figure that corrections officials say has declined. Of those, 48 percent were with spouses. The rest were with family members such as children or parents.

Studies cited by Yale law students in a 2012 review of family visitation programs showed that the programs could work as powerful incentives for good behavior, help reduce sexual activity among prisoners and help strengthen families.

Though what qualifies prisoners for the visits varies from state to state, all must have records of good behavior and be legally married. In most, prisoners in maximum security or on death row are denied the visits. Federal prisons do not allow them.

Mississippi ended its more extensive family visitations last year but left in place the hourlong visits, which since their inception a century ago have been designed more as a way to control inmates than nurture relationships.

“Conjugal visits have been a privilege,” said Tara Booth, a spokeswoman for the Mississippi Corrections Department. “So in that sense, it has, as other internal opportunities, helped to maintain order.”

The notion of allowing prisoners to have sex was born here shortly after Parchman Farm opened in 1903 as a series of work camps on 1,600 acres of rich Delta farmland. Inmates, most of whom were black, were used as free farm labor in an arrangement not that far removed from slavery.

Set in the middle of the birthplace of the blues, Parchman Farm has been the subject of many songs written by classic bluesmen like Bukka White and others who did time here.

The warden at the time believed sex could be used to compel black men to work harder in the fields, according to a history on the practice produced in the 1970s by Tyler Fletcher, who founded the department of criminal justice at the University of Southern Mississippi in 1973. So black prisoners were allowed time on Sunday with spouses or, more often, prostitutes.

By the 1940s, makeshift lean-tos and shacks built by inmates for the visits gave way to formal facilities, and white inmates were more likely participants than black ones.

Announced in December, the decision to stop the hourlong conjugal visits came as a surprise to the handful of prison spouses who rely on them. Several have taken to Facebook and other online forums and written to lawmakers to try to save what they say is an essential part of their relationships. A Mississippi prisoners’ advocacy group and a Memphis-based civil rights organization have planned a rally for Friday in Jackson, the state capital, to protest the policy change.

But State Representative Richard Bennett, Republican of Long Beach, wants the practice stopped, and he said no amount of protest would change his mind.

He said he learned about conjugal visits a few years ago when an elementary school principal told him a student of hers had shown up with a photograph of a new sibling. The student’s mother was incarcerated. The baby had been conceived during a conjugal visit.

In 2012, Mr. Bennett introduced a bill to end the visits. It did not get much attention, so he will try again when the Legislature meets this month. He said he was aware of Mr. Epps’s plans, but wanted a permanent ban. Officials have not offered any figures on the number of babies born or the program’s cost.

“I don’t think it’s fair to the children conceived and to the taxpayers,” he said. “You are in prison for a reason. You are in there to pay your debt, and conjugal visits should not be part of the deal.”

But Tina Perry, 49, a production manager at a small newspaper in eastern Mississippi, said the spouses of prisoners should not be forced to suffer any more than they already do. And the state, she said, should not take away something that is inexpensive and infrequent but essential.

She has been visiting her husband in prison every couple of months for eight years. He is serving time for molesting his former wife’s daughter, and has 19 more years to go. Ms. Perry said he was innocent. She called the surroundings, a small room with a thin mattress, “nasty” but said it was an hour she treasured nonetheless.

“It’s your husband,” she said. “You take what you can get.”

Ms. Fisher, whose husband is facing 60 years, said she was heartbroken because no more conjugal visits meant no children.

“Let me have that option,” she said. “I feel like they are taking away my choice.”

But officials who want the practice to be stopped say the state should not be helping to produce children who will be raised by single parents and possibly need state support.

There are concerns, too, about cost and H.I.V. transmission.

Women interviewed about the visits said they would be willing to pay to defray costs. And they made it clear that the visits were not about the sex. They are about privacy in a world where every letter is opened, every call monitored. Regular visits are crowded with other prisoners and their families.

“You never just get husband and wife time,” said Amy Parsons, an office worker in Arkansas who drives eight hours to see her husband, who was convicted of aggravated assault. His release date is 2022.

“It’s not romantic, but it doesn’t matter,” she said. “I just want people to realize it’s about the alone time with your husband. I understand they are in there for a reason. Obviously they did something wrong. But they are human, too. So are we.”

Prison Fellowship

Four Resources for Spouses and Families Affected by Incarceration

February 12, 2019 by Emily Harris Greene

Tracey was arrested 10 days after her honeymoon and faced a 40-year prison sentence and separation from her four children and new husband Darreyl.

George's drug addiction and life of crime weighed heavily on his marriage, and his wife wasn't sure if she could continue supporting him.

Shane's relationship with his three children was destroyed after an ugly divorce, painful addiction, and two prisons stints.

For spouses and families separated by crime and incarceration, maintaining a relationship is complicated. There is often a lot of pain and broken trust that must be dealt with. Restricted access and limited visitation can make it hard for those on opposite sides of prison walls to stay in contact. In addition, prisoners are often transferred to different facilities, and many end up hundreds of miles away from home.

When prisoners can stay connected to their families, their chances of recidivism drop. Maintaining those relationships and choosing to walk alongside loved ones during their incarceration takes a lot of effort. While every situation is different, here are several resources that may help.

FOUR RESOURCES FOR SPOUSES AND FAMILIES

Behind prison walls, the days can feel long and monotonous. Many prisoners look forward to mail, phone calls, and visits from their loved ones. And loved ones on the outside have struggles of their own. Positive contact can help everyone make it through a prison sentence.

Every correctional facility has its own set of rules and expectations. Visits to prisoners may require a lot of planning. In this resource, we offer several tips to consider before, during, and after a prison visit.

When a parent goes to prison, it can have a traumatic and lasting impact on children. If it's appropriate and permitted to do so, building a meaningful and positive relationship between your children and their incarcerated parent may not be easy, but it's possible and may provide significant benefits to children's well-being over time.

Originally written for Inside Journal ® , a quarterly newspaper written specifically for incarcerated men and women, the tips in this article may also benefit spouses left on the outside.

RESTORATION IS POSSIBLE

Tracey wouldn't have blamed Darreyl if he had chosen to leave her after her conviction. Nor did she expect her children to forgive her. But God had other plans. Darreyl chose to stay during that difficult season of marriage, and he brought their children regularly to visit. Thinking back on those days "brings me to tears," Tracey says. "God is faithful."

While in prison, George surrendered his life to Christ and sought sobriety. His wife Irene immediately noticed a change in him. The husband and wife "started learning about each other all over again," Irene shares. "I'm blessed that I was able to stick it out. We're still married to this day . That's a miracle."

Broken relationships take time to heal, but by God's grace, Shane reconnected with his children . It was a journey to reconciliation that began the day his eldest daughter decided to answer his phone call—something his children hadn't done for three years. The conversation was painful, but it was a turning point for the family. Today, Shane is out of prison and able to spend time with his kids. It hasn't been an easy road, but the family is learning to embrace one another again.

Choosing to walk alongside incarcerated loved ones through their sentences can be difficult. It might seem impossible, but with God, all things are possible—even the restoration of strained and broken relationships.

DID YOU ENJOY THIS ARTICLE?

Make sure you don' t miss out on any of our helpful articles and incredible transformation stories! Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter, and you' ll get great content delivered directly to your inbox.

- First Name *

- Last Name *

Your privacy is safe with us. We will never sell, trade, or share your personal information.

JOIN OUR ONLINE COMMUNITY

Recommended links.

- Ways to Donate

- Inspirational Stories

- Angel Tree Program

- Prison Fellowship Academy

- Justice Reform

- For Families & Friends of Prisoners

- For Churches & Angel Tree Volunteers

- Warden Exchange

JOIN RESTORATION PARTNERS AND WITNESS GOD RESTORE LIVES

Restoration Partners give monthly to bring life-changing prison ministry programs to incarcerated men and women across the country.

Stream ID Live

Never miss a mystery.

Sign in with your cable subscription

Watch Free Series

On the case with paula zahn, see no evil, bride killa, i married a mobster, deadline: crime with tamron hall, homicide hunter: lt. joe kenda, til death do us part, jared from subway: catching a monster, the hillside strangler: mind of a monster, twisted sisters, the playboy murders, unusual suspects, trending on id, evil lives here, new york post reports: off the record, mean girl murders, murder in the heartland, quiet on set: the dark side of kids tv, signs of a psychopath, continue watching, new episodes.

S27 E5 When the Music’s Over

S9 E3 Summer's Deadly Fling

Bail Jumpers

S1 E10 Chicken Blood, Turtles, Runner

S1 E9 Outlaws, Mars, Busted Ceiling

S8 E6 Desperate Measures

Lethally Blonde

S1 E2 The Porn Identity

S2 E2 Church Camp Killer

S7 E8 I Am the Weirdest Guy

S7 E7 Make Sure You Get My Good Side

S15 E6 I Saw Myself on Tape

My Episodes

If you like quiet on set: the dark side of kids tv, undercover underage, jonbenét: an american murder mystery, let us prey: a ministry of scandals, people magazine investigates, the price of glee, gypsy's revenge, the curious case of natalia grace, link your tv provider to unlock thousands of episodes from the discovery family of networks..

Network availability may vary with your TV package.

Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

For california, colorado, connecticut, virginia and utah residents only, allow sale, sharing or use of my personal information for targeted advertising.

If you switch this toggle to “no,” we will not sell or share your personal information with third parties for advertising targeted to this browser/device. Please see our Opt-Out Form for additional preferences.

Global Privacy Control (GPC)

When a GPC signal is not detected, we sell and share your personal information unless you toggle "no" above.

Cookie List

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

What Really Happens During Overnight Prison Visits

Although conjugal, or “extended,” visits play a huge role in prison lore, in reality, very few inmates have access to them. 20 years ago, 17 states offered these programs. Today, just four — California, Connecticut, New York, and Washington — do. No federal prison offers extended, private visitation. Last April, New Mexico became the latest state to cancel conjugal visits for prisoners after a local television station revealed that a convicted killer, Michael Guzman, had fathered four children with several different wives while in prison. Mississippi had made a similar decision in January 2014.

Related: How Women In Prison Use Sharpies & Jolly Ranchers To Make Makeup

A Stay At The “Boneyard” In every state that offers extended visits, good prison behavior is a prerequisite, and inmates convicted of sex crimes or domestic violence, or who have life sentences, are typically excluded. The visits range from one hour to three days and happen as often as once per month. They take place in trailers, small apartments, or “family cottages” that are built just for this purpose (and sometimes referred to as “ boneyards ”). At the MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Connecticut, units are set up to imitate homes. Each apartment has two bedrooms, a dining room, and a living room with a TV, DVD player, playing cards, a Jenga game, and dominoes. In Washington, any DVD a family watches must be G-rated. Kitchens are typically fully functional, and visitors can bring in fresh ingredients or cooked food from the outside. In California, inmates and their visitors must line up for inspection every four hours throughout the weekend visit, even in the middle of the night. Many prisons provide condoms for free. In New Mexico, before the extended visitation program was canceled, the prisoner’s spouse could be informed if the inmate had tested positive for a sexually transmitted infection. After the visit, both inmates and visitors are searched, and inmates typically have their urine tested to check for drugs or alcohol, which are strictly prohibited.

Related: So You Want To Try Pegging