What Was the Grand Tour and Where Did People Go?

Freelance Travel and Music Writer

Nowadays, it’s so easy to pack a bag and hop on a flight or interrail across Europe’s railway at your own leisure. But what if it was known as a right of passage, made no easier by the fact that there was no such modern luxury? Welcome to the Grand Tour – and we’re not talking about Jeremy Clarkson’s TV series …

What was the grand tour all about.

The Grand Tour was a trip of Europe, typically undertaken by young men, which begun in the 17th century and went through to the mid-19th. Women over the age of 21 would occasionally partake, providing they were accompanied by a chaperone from their family. The Grand Tour was seen as an educational trip across Europe, usually starting in Dover, and would see young, wealthy travellers search for arts and culture. Though travelling was not as easy back then, mostly thanks to no rail routes like today, those on The Grand Tour would often have a healthy supply of funds in order to enjoy themselves freely.

What did travellers get up to?

Of course, in the 17th century, there was no such thing as the internet, making discovering things while sat on the other side of the world near impossible. Cultural integration was not yet fully-fledged and nothing like we experience today, so the only way to understand different ways of life was to experience them yourself. Hence why so many people set off for the Grand Tour – the ultimate trip across Europe!

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Typical routes taken on the Grand Tour

Travellers (occompanied by a tutor) would often start around the South East region and head in to France, where a coach would often be rented should the party be wealthy enough. Occasionally, the coaches would need to be disassembled in order to cross difficult terrain such as the Alps.

Once passing through Calais and Paris, a typical journey would include a stop-off in Switzerland before crossing the Alps in to Northern Italy. Here’s where the wealth really comes in to play – as luggage and methods of transport would need to be dismantled and carried manually – as really rich travellers would often employ servants to carry everything for them.

Of course, Italy is a highly cultural country and famous for its art and historic buildings, so travellers would spend longer here. Turin, Florence, Rome, Pompeii and Venice would be amongst the cities visited, generally enticing those in to extended stays.

On the return leg, travellers would visit Germany and occasionally Austria, including study time at universities such as Munich, before heading to Holland and Flanders, ahead of crossing the Channel back to Dover.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Guides & Tips

Five places that look even more beautiful covered in snow.

The Best Places in Europe to Visit in 2024

The Best Places to Travel in August 2024

The Best Places to Travel in May 2024

Places to Stay

The best private trips to book for your classical studies class.

The Best Private Trips to Book for Your Religious Studies Class

The Best Private Trips to Book With Your Support Group

The Best Rail Trips to Take in Europe

The Best Trips for Sampling Amazing Mediterranean Food

The Best European Trips for Foodies

The Best Private Trips to Book in Europe

The Best Private Trips to Book in Southern Europe

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 1702695

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

What was the Grand Tour?

Find out about the travel phenomenon that became popular amongst the young nobility of England

Art, antiquity and architecture: the Grand Tour provided an opportunity to discover the cultural wonders of Europe and beyond.

Popular throughout the 18th century, this extended journey was seen as a rite of passage for mainly young, aristocratic English men.

As well as marvelling at artistic masterpieces, Grand Tourists brought back souvenirs to commemorate and display their journeys at home.

One exceptional example forms the subject of a new exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. Canaletto’s Venice Revisited brings together 24 of Canaletto’s Venetian views, commissioned in 1731 by Lord John Russell following his visit to Venice.

Find out more about this travel phenomenon – and uncover its rich cultural legacy.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

The origins of the Grand Tour

The development of the Grand Tour dates back to the 16th century.

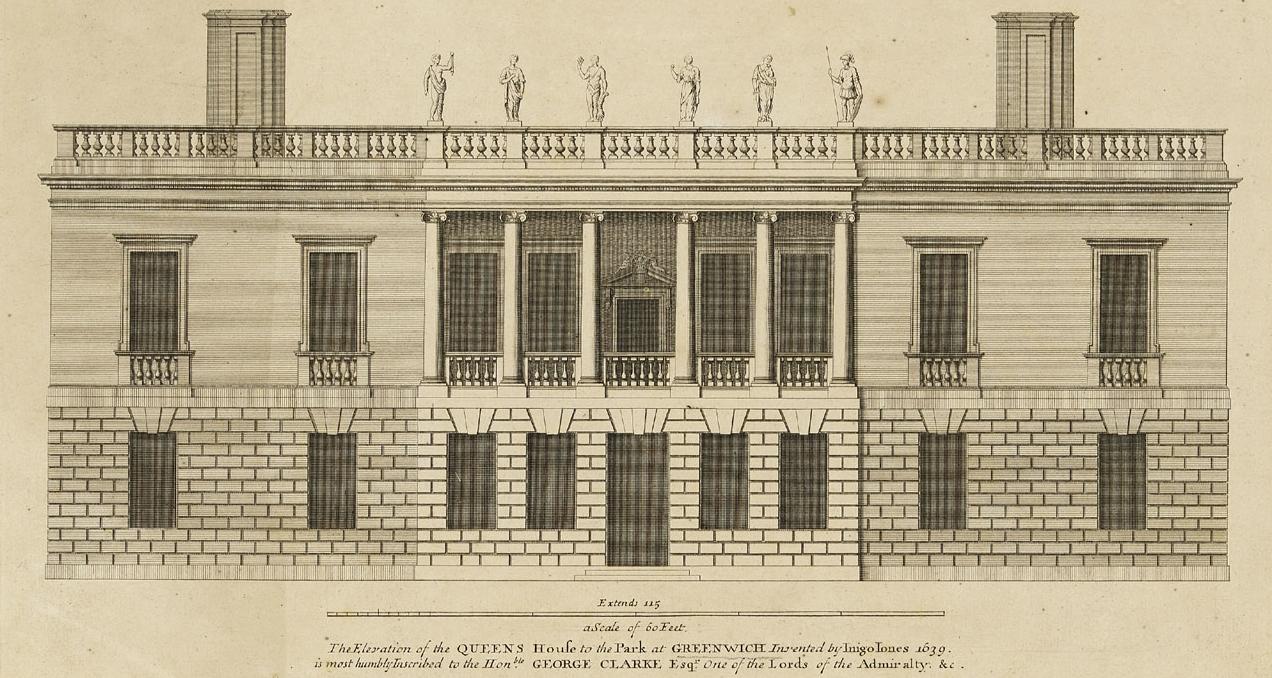

One of the earliest Grand Tourists was the architect Inigo Jones , who embarked on a tour of Italy in 1613-14 with his patron Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel.

Jones visited cities such as Parma, Venice and Rome. However, it was Naples that proved the high point of his travels.

Jones was particularly fascinated by the San Paolo Maggiore, describing the church as “one of the best things that I have ever seen.”

Jones’s time in Italy shaped his architectural style. In 1616, Jones was commissioned to design the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne of Denmark , the wife of King James I. Completed in around 1636, the house was the first classical building in England.

The expression ‘Grand Tour’ itself comes from 17th century travel writer and Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, who used it in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy, published in 1670.

By the 18th century, the Grand Tour had reached its zenith. Despite Anglo-French wars in 1689-97 and 1702-13, this was a time of relative stability in Europe, which made travelling across the continent easier.

The Grand Tour route

For young English aristocrats, embarking on the Grand Tour was seen as an important rite of passage.

Accompanied by a tutor, a Grand Tourist’s route typically involved taking a ship across the English Channel before travelling in a carriage through France, stopping at Paris and other major cities.

Italy was also a popular destination thanks to the art and architecture of places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Milan and Naples. More adventurous travellers ventured to Sicily or even sailed across to Greece. The average Grand Tour lasted for at least a year.

As Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich explains, this extended journey marked the culmination of a Grand Tourist’s education.

“The Grand Tourists would have received an education that was grounded in the Classics,” she says. “During their travels to the continent, they would have seen classical ruins and read Latin and Greek texts. The Grand Tour was also an opportunity to take in more recent culture, such as Renaissance paintings, and see contemporary artists at work.”

As well as educational opportunities, the Grand Tour was linked with independence. Places such as Venice were popular with pleasure seekers, boasting gambling houses and occasions for drinking and partying.

“On the Grand Tour, there’s a sense that travellers are gaining some of their independence and having a lesson in the ways of the world,” Gazzard explains. “For visitors to Venice, there were opportunities to behave beyond the social norms, with the masquerade and the carnival.”

Art and the Grand Tour

Bound up with the idea of independence was the need to collect souvenirs, which the Grand Tourists could display in their homes.

“The ownership of property was tied to status, so creating a material legacy was really important for the Grand Tourists in order to solidify their social standing amongst their peers,” says Gazzard. “They were looking to spend money and buy mementos to prove they went on the trip.”

The works of artists such as those of the 18th century view painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (known as Canaletto ) were especially popular with Grand Tourists. Prized for their detail, Canaletto’s artworks captured the landmarks and scenes of everyday Venetian life, from festive scenes to bustling traffic on the Grand Canal .

In 1731, Lord John Russell, the future 4th Duke of Bedford, commissioned Canaletto to create 24 Venetian views following his visit to the city.

Lord John Russell is known to have paid at least £188 for the set – over five times the annual earnings of a skilled tradesperson at the time.

“Canaletto’s work was portable and collectible,” says Gazzard. “He adopted a smaller size for his canvases so they could be rolled up and shipped easily.”

These detailed works, now part of the world famous collection at Woburn Abbey, form the centrepiece of Canaletto’s Venice Revisited at the National Maritime Museum .

Who was Canaletto?

The legacy of the Grand Tour

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 marked the end of the Grand Tour. However, its legacy is still keenly felt.

The desire to explore and learn about different places and cultures through travel continues to endure. The legacy of the Grand Tour can also be seen in the artworks and objects that adorn the walls of stately homes and museums, and the many cultural influences that travellers brought back to Britain.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

Main image: The Piazza San Marco looking towards the Basilica San Marco and the Campanile by Canaletto . From the Woburn Abbey Collection . Canaletto painting in body copy: Regatta on Grand Canal by Canaletto From the Woburn Abbey Collection

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

What Was the Grand Tour of Europe?

Lucy Davidson

26 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

In the 18th century, a ‘Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for wealthy young men. Essentially an elaborate form of finishing school, the tradition saw aristocrats travel across Europe to take in Greek and Roman history, language and literature, art, architecture and antiquity, while a paid ‘cicerone’ acted as both a chaperone and teacher.

Grand Tours were particularly popular amongst the British from 1764-1796, owing to the swathes of travellers and painters who flocked to Europe, the large number of export licenses granted to the British from Rome and a general period of peace and prosperity in Europe.

However, this wasn’t forever: Grand Tours waned in popularity from the 1870s with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel and the popularity of Thomas Cook’s affordable ‘Cook’s Tour’, which made mass tourism possible and traditional Grand Tours less fashionable.

Here’s the history of the Grand Tour of Europe.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

In his 1670 guidebook The Voyage of Italy , Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassells coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, culture and history. The primary demographic of Grand Tour travellers changed little over the years, though primarily upper-class men of sufficient means and rank embarked upon the journey when they had ‘come of age’ at around 21.

‘Goethe in the Roman Campagna’ by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Rome 1787.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Grand Tours also became fashionable for women who might be accompanied by a spinster aunt as a chaperone. Novels such as E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View reflected the role of the Grand Tour as an important part of a woman’s education and entrance into elite society.

Increasing wealth, stability and political importance led to a more broad church of characters undertaking the journey. Prolonged trips were also taken by artists, designers, collectors, art trade agents and large numbers of the educated public.

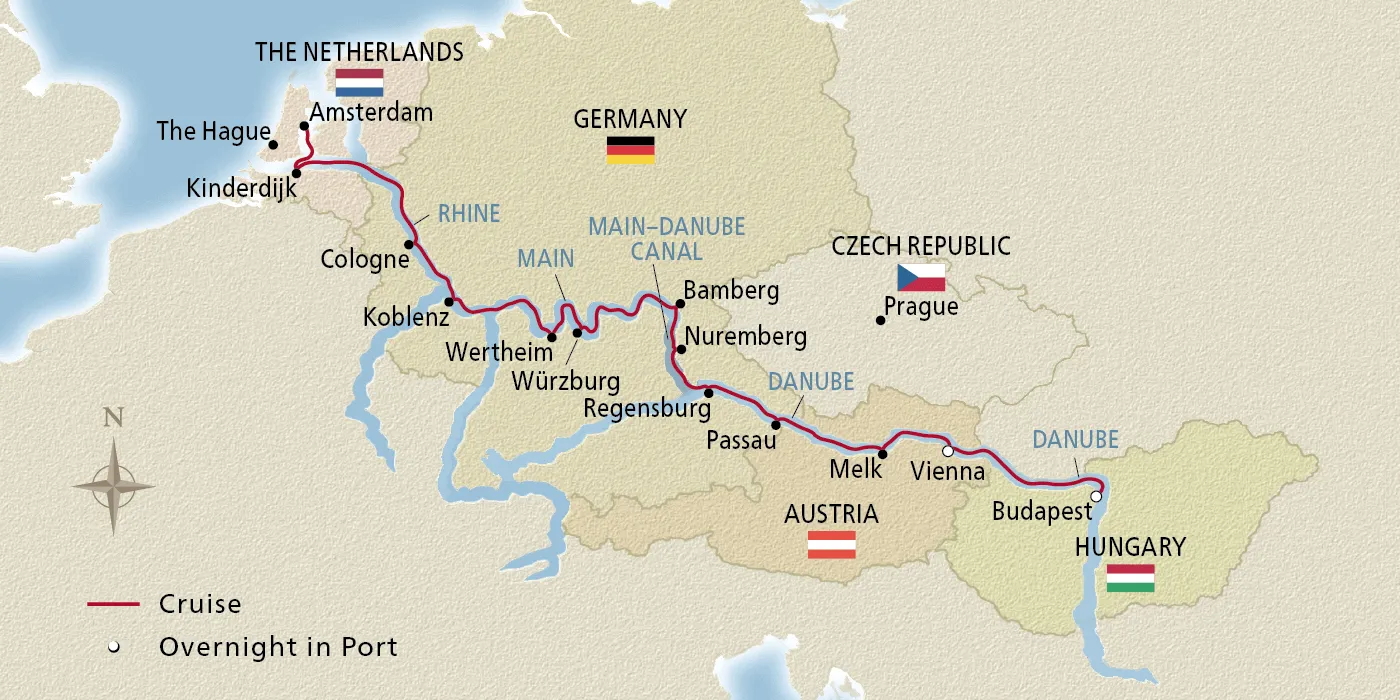

What was the route?

The Grand Tour could last anything from several months to many years, depending on an individual’s interests and finances, and tended to shift across generations. The average British tourist would start in Dover before crossing the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium or Le Havre and Calais in France. From there the traveller (and if wealthy enough, group of servants) would hire a French-speaking guide before renting or acquiring a coach that could be both sold on or disassembled. Alternatively, they would take the riverboat as far as the Alps or up the Seine to Paris .

Map of grand tour taken by William Thomas Beckford in 1780.

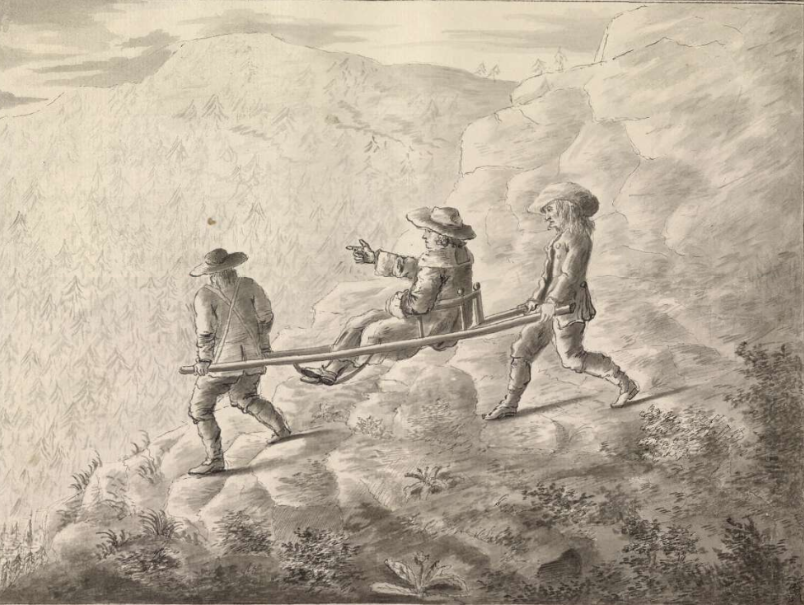

From Paris, travellers would normally cross the Alps – the particularly wealthy would be carried in a chair – with the aim of reaching festivals such as the Carnival in Venice or Holy Week in Rome. From there, Lucca, Florence, Siena and Rome or Naples were popular, as were Venice, Verona, Mantua, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Milan, Turin and Mont Cenis.

What did people do on the Grand Tour?

A Grand Tour was both an educational trip and an indulgent holiday. The primary attraction of the tour lay in its exposure of the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, such as the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, as well as the chance to enter fashionable and aristocratic European society.

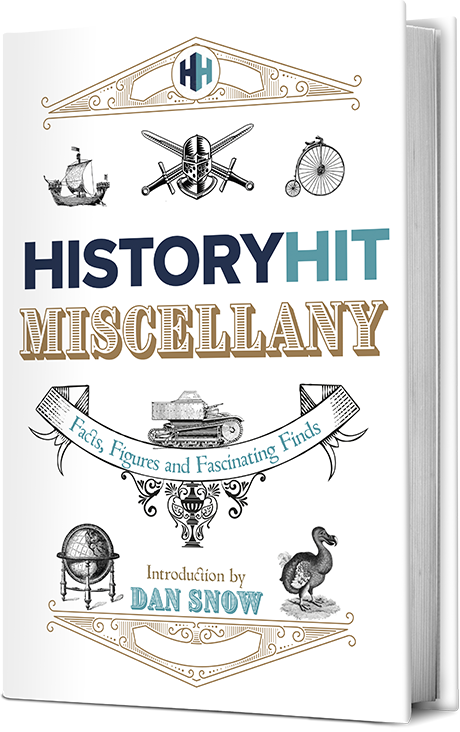

Johann Zoffany: The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper, c. 1775.

In addition, many accounts wrote of the sexual freedom that came with being on the continent and away from society at home. Travel abroad also provided the only opportunity to view certain works of art and potentially the only chance to hear certain music.

The antiques market also thrived as lots of Britons, in particular, took priceless antiquities from abroad back with them, or commissioned copies to be made. One of the most famous of these collectors was the 2nd Earl of Petworth, who gathered or commissioned some 200 paintings and 70 statues and busts – mainly copies of Greek originals or Greco-Roman pieces – between 1750 and 1760.

It was also fashionable to have your portrait painted towards the end of the trip. Pompeo Batoni painted over 175 portraits of travellers in Rome during the 18th century.

Others would also undertake formal study in universities, or write detailed diaries or accounts of their experiences. One of the most famous of these accounts is that of US author and humourist Mark Twain, whose satirical account of his Grand Tour in Innocents Abroad became both his best selling work in his own lifetime and one of the best-selling travel books of the age.

Why did the popularity of the Grand Tour decline?

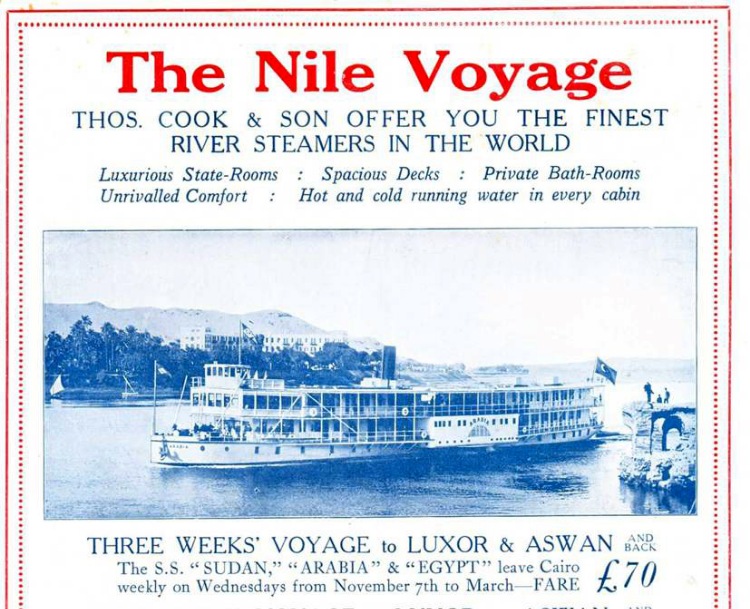

A Thomas Cook flyer from 1922 advertising cruises down the Nile. This mode of tourism has been immortalised in works such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie.

The popularity of the Grand Tour declined for a number of reasons. The Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1815 marked the end of the heyday of the Grand Tour, since the conflict made travel difficult at best and dangerous at worst.

The Grand Tour finally came to an end with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel as a result of Thomas Cook’s ‘Cook’s Tour’, a byword of early mass tourism, which started in the 1870s. Cook first made mass tourism popular in Italy, with his train tickets allowing travel over a number of days and destinations. He also introduced travel-specific currencies and coupons which could be exchanged at hotels, banks and ticket agencies which made travelling easier and also stabilised the new Italian currency, the lira.

As a result of the sudden potential for mass tourism, the Grand Tour’s heyday as a rare experience reserved for the wealthy came to a close.

Can you go on a Grand Tour today?

Echoes of the Grand Tour exist today in a variety of forms. For a budget, multi-destination travel experience, interrailing is your best bet; much like Thomas Cook’s early train tickets, travel is permitted along many routes and tickets are valid for a certain number of days or stops.

For a more upmarket experience, cruising is a popular choice, transporting tourists to a number of different destinations where you can disembark to enjoy the local culture and cuisine.

Though the days of wealthy nobles enjoying exclusive travel around continental Europe and dancing with European royalty might be over, the cultural and artistic imprint of a bygone Grand Tour era is very much alive.

To plan your own Grand Tour of Europe, take a look at History Hit’s guides to the most unmissable heritage sites in Paris , Austria and, of course, Italy .

You May Also Like

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case

18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

The Travels of European Twenty-Somethings

Print Collector/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Geography, University of California - Davis

The French Revolution marked the end of a spectacular period of travel and enlightenment for European youth, particularly from England. Young English elites of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often spent two to four years touring around Europe in an effort to broaden their horizons and learn about language , architecture , geography, and culture in an experience known as the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour, which didn't come to an end until the close of the eighteenth century, began in the sixteenth century and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Read to find out what started this event and what the typical Tour entailed.

Origins of the Grand Tour

Privileged young graduates of sixteenth-century Europe pioneered a trend wherein they traveled across the continent in search of art and cultural experiences upon their graduation. This practice, which grew to be wildly popular, became known as the Grand Tour, a term introduced by Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy . Specialty guidebooks, tour guides, and other aspects of the tourist industry were developed during this time to meet the needs of wealthy 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors as they explored the European continent.

These young, classically-educated Tourists were affluent enough to fund multiple years abroad for themselves and they took full advantage of this. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England in order to communicate with and learn from people they met in other countries. Some Tourists sought to continue their education and broaden their horizons while abroad, some were just after fun and leisurely travels, but most desired a combination of both.

Navigating Europe

A typical journey through Europe was long and winding with many stops along the way. London was commonly used as a starting point and the Tour was usually kicked off with a difficult trip across the English Channel.

Crossing the English Channel

The most common route across the English Channel, La Manche, was made from Dover to Calais, France—this is now the path of the Channel Tunnel. A trip from Dover across the Channel to Calais and finally into Paris customarily took three days. After all, crossing the wide channel was and is not easy. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Tourists risked seasickness, illness, and even shipwreck on this first leg of travel.

Compulsory Stops

Grand Tourists were primarily interested in visiting cities that were considered major centers of culture at the time, so Paris, Rome, and Venice were not to be missed. Florence and Naples were also popular destinations but were regarded as more optional than the aforementioned cities.

The average Grand Tourist traveled from city to city, usually spending weeks in smaller cities and up to several months in the three major ones. Paris, France was the most popular stop of the Grand Tour for its cultural, architectural, and political influence. It was also popular because most young British elite already spoke French, a prominent language in classical literature and other studies, and travel through and to this city was relatively easy. For many English citizens, Paris was the most impressive place visited.

Getting to Italy

From Paris, many Tourists proceeded across the Alps or took a boat on the Mediterranean Sea to get to Italy, another essential stopping point. For those who made their way across the Alps, Turin was the first Italian city they'd come to and some remained here while others simply passed through on their way to Rome or Venice.

Rome was initially the southernmost point of travel. However, when excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) began, these two sites were added as major destinations on the Grand Tour.

Features of the Grand Tour

The vast majority of Tourists took part in similar activities during their exploration with art at the center of it all. Once a Tourist arrived at a destination, they would seek housing and settle in for anywhere from weeks to months, even years. Though certainly not an overly trying experience for most, the Grand Tour presented a unique set of challenges for travelers to overcome.

While the original purpose of the Grand Tour was educational, a great deal of time was spent on much more frivolous pursuits. Among these were drinking, gambling, and intimate encounters—some Tourists regarded their travels as an opportunity to indulge in promiscuity with little consequence. Journals and sketches that were supposed to be completed during the Tour were left blank more often than not.

Visiting French and Italian royalty as well as British diplomats was a common recreation during the Tour. The young men and women that participated wanted to return home with stories to tell and meeting famous or otherwise influential people made for great stories.

The study and collection of art became almost a nonoptional engagement for Grand Tourists. Many returned home with bounties of paintings, antiques, and handmade items from various countries. Those that could afford to purchase lavish souvenirs did so in the extreme.

Arriving in Paris, one of the first destinations for most, a Tourist would usually rent an apartment for several weeks or months. Day trips from Paris to the French countryside or to Versailles (the home of the French monarchy) were common for less wealthy travelers that couldn't pay for longer outings.

The homes of envoys were often utilized as hotels and food pantries. This annoyed envoys but there wasn't much they could do about such inconveniences caused by their citizens. Nice apartments tended to be accessible only in major cities, with harsh and dirty inns the only options in smaller ones.

Trials and Challenges

A Tourist would not carry much money on their person during their expeditions due to the risk of highway robberies. Instead, letters of credit from reputable London banks were presented at major cities of the Grand Tour in order to make purchases. In this way, tourists spent a great deal of money abroad.

Because these expenditures were made outside of England and therefore did not bolster England's economy, some English politicians were very much against the institution of the Grand Tour and did not approve of this rite of passage. This played minimally into the average person's decision to travel.

Returning to England

Upon returning to England, tourists were meant to be ready to assume the responsibilities of an aristocrat. The Grand Tour was ultimately worthwhile as it has been credited with spurring dramatic developments in British architecture and culture, but many viewed it as a waste of time during this period because many Tourists did not come home more mature than when they had left.

The French Revolution in 1789 halted the Grand Tour—in the early nineteenth century, railroads forever changed the face of tourism and foreign travel.

- Burk, Kathleen. "The Grand Tour of Europe". Gresham College, 6 Apr. 2005.

- Knowles, Rachel. “The Grand Tour.” Regency History , 30 Apr. 2013.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History , The Met Museum, Oct. 2003.

- A Beginner's Guide to the Enlightenment

- Architecture in France: A Guide For Travelers

- The History of Venice

- A Brief History of Rome

- Female European Historical Figures: 1500 - 1945

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

- The 12 Best Books on the French Revolution

- 18 Key Thinkers of the Enlightenment

- Architecture in Italy for the Lifelong Learner

- Mansions, Manors, and Grand Estates in the United States

- Geography of France

- The Rise of Islamic Geography in the Middle Ages

- Biography of Marco Polo, Merchant and Explorer

- William Wordsworth

- Women Artists of the Seventeenth Century: Renaissance and Baroque

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The grand tour.

Marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons

Piazza San Marco

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

Autre Vue Particulière de Paris depuis Nôtre Dame, Jusques au Pont de la Tournelle

Jacques Rigaud

Imaginary View of Venice, houses at left with figures on terraces, a domed church at center in the background, boats and boat-sheds below, and a seated man observing from a wall at right in the foreground, from 'Views' (Vedute altre prese da i luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal)

The Piazza del Popolo (Veduta della Piazza del Popolo), from "Vedute di Roma"

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Vue de la Grande Façade du Vieux Louvre

View of St. Peter's and the Vatican from the Janiculum

Richard Wilson

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)

Anton Raphael Mengs

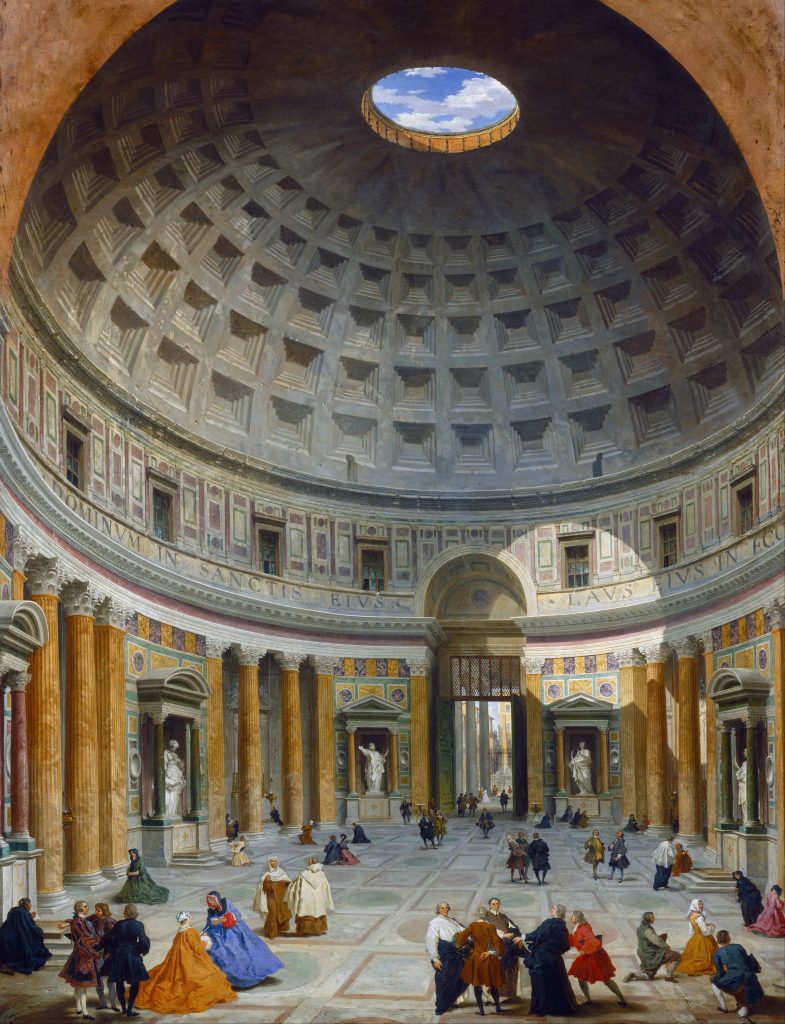

Modern Rome

Giovanni Paolo Panini

Ancient Rome

Portrait of a Young Man

Pompeo Batoni

Gardens of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli

Charles Joseph Natoire

Veduta dell'Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo, from: 'Vedute di Roma' (Views of Rome)

View of the Villa Lante on the Janiculum in Rome

John Robert Cozens

The Girandola at the Castel Sant'Angelo

Designed and hand colored by Louis Jean Desprez

Dining room from Lansdowne House

After a design by Robert Adam

The Burial of Punchinello

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Portland vase

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2003

Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for young aristocrats to visit Paris, Venice, Florence, and above all Rome, as the culmination of their classical education. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Tour, a practice that introduced Englishmen, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans to the art and culture of France and Italy for the next 300 years. Travel was arduous and costly throughout the period, possible only for a privileged class—the same that produced gentleman scientists, authors, antiquaries, and patrons of the arts.

The Objectives of the Grand Tour The Grand Tourist was typically a young man with a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature as well as some leisure time, some means, and some interest in art. The German traveler Johann Joachim Winckelmann pioneered the field of art history with his comprehensive study of Greek and Roman sculpture ; he was portrayed by his friend Anton Raphael Mengs at the beginning of his long residence in Rome ( 48.141 ). Most Grand Tourists, however, stayed for briefer periods and set out with less scholarly intentions, accompanied by a teacher or guardian, and expected to return home with souvenirs of their travels as well as an understanding of art and architecture formed by exposure to great masterpieces.

London was a frequent starting point for Grand Tourists, and Paris a compulsory destination; many traveled to the Netherlands, some to Switzerland and Germany, and a very few adventurers to Spain, Greece, or Turkey. The essential place to visit, however, was Italy. The British traveler Charles Thompson spoke for many Grand Tourists when in 1744 he described himself as “being impatiently desirous of viewing a country so famous in history, which once gave laws to the world; which is at present the greatest school of music and painting, contains the noblest productions of statuary and architecture, and abounds with cabinets of rarities , and collections of all kinds of antiquities.” Within Italy, the great focus was Rome, whose ancient ruins and more recent achievements were shown to every Grand Tourist. Panini’s Ancient Rome ( 52.63.1 ) and Modern Rome ( 52.63.2 ) represent the sights most prized, including celebrated Greco-Roman statues and views of famous ruins, fountains, and churches. Since there were few museums anywhere in Europe before the close of the eighteenth century, Grand Tourists often saw paintings and sculptures by gaining admission to private collections, and many were eager to acquire examples of Greco-Roman and Italian art for their own collections. In England, where architecture was increasingly seen as an aristocratic pursuit, noblemen often applied what they learned from the villas of Palladio in the Veneto and the evocative ruins of Rome to their own country houses and gardens .

The Grand Tour and the Arts Many artists benefited from the patronage of Grand Tourists eager to procure mementos of their travels. Pompeo Batoni painted portraits of aristocrats in Rome surrounded by classical staffage ( 03.37.1 ), and many travelers bought Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s prints of Roman views, including ancient structures like the Colosseum ( 59.570.426 ) and more recent monuments like the Piazza del Popolo ( 37.45.3[49] ), the dazzling Baroque entryway to Rome. Some Grand Tourists invited artists from home to accompany them throughout their travels, making views specific to their own itineraries; the British artist Richard Wilson, for example, made drawings of Italian places while traveling with the earl of Dartmouth in the mid-eighteenth century ( 1972.118.294 ).

Classical taste and an interest in exotic customs shaped travelers’ itineraries as well as their reactions. Gothic buildings , not much esteemed before the late eighteenth century, were seldom cause for long excursions, while monuments of Greco-Roman antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and the classical Baroque tradition received praise and admiration. Jacques Rigaud’s views of Paris were well suited to the interests of Grand Tourists, displaying, for example, the architectural grandeur of the Louvre, still a royal palace, and the bustle of life along the Seine ( 53.600.1191 ; 53.600.1175 ). Canaletto’s views of Venice ( 1973.634 ; 1988.162 ) were much prized, and other works appealed to Northern travelers’ interest in exceptional fêtes and customs: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo ‘s Burial of Punchinello ( 1975.1.473 ), for instance, is peopled with characters from the Venetian carnival, and a print by Francesco Piranesi and Louis Jean Desprez depicts the Girandola, a spectacular fireworks display held at the Castel Sant’Angelo ( 69.510 ).

The Grand Tour and Neoclassical Taste The Grand Tour gave concrete form to northern Europeans’ ideas about the Greco-Roman world and helped foster Neoclassical ideals . The most ambitious tourists visited excavations at such sites as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Tivoli, and purchased antiquities to decorate their homes. The third duke of Beaufort brought from Rome the third-century work named the Badminton Sarcophagus ( 55.11.5 ) after the house where he proudly installed it in Gloucestershire. The dining rooms of Robert Adam’s interiors typically incorporated classical statuary; the nine lifesized figures set in niches in the Lansdowne dining room ( 32.12 ) were among the many antiquities acquired by the second earl of Shelburne, whose collecting activities accelerated after 1771, when he visited Italy and met Gavin Hamilton, a noted antiquary and one of the first dealers to take an interest in Attic ceramics, then known as “Etruscan vases.” Early entrepreneurs recognized opportunities created by the culture of the Grand Tour: when the second duchess of Portland obtained a Roman cameo glass vase in a much-publicized sale, Josiah Wedgwood profited from the manufacture of jasper reproductions ( 94.4.172 ).

Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Black, Jeremy. The British and the Grand Tour . London: Croom Helm, 1985.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Black, Jeremy. France and the Grand Tour . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Haskell, Francis, and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wilton, Andrew, and Ilaria Bignamini, eds. The Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century . Exhibition catalogue. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Baroque Rome .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Opera .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- Baroque Rome

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- Neoclassicism

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

- Architecture in Renaissance Italy

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- The Augustan Villa at Boscotrecase

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- Commedia dell’arte

- The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait

- Exoticism in the Decorative Arts

- Gardens in the French Renaissance

- Gardens of Western Europe, 1600–1800

- George Inness (1825–1894)

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

- Images of Antiquity in Limoges Enamels in the French Renaissance

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Joachim Tielke (1641–1719)

- John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872)

- Photographers in Egypt

- The Printed Image in the West: Etching

- Roman Copies of Greek Statues

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Balkan Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Ancient Roman Art

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Classical Ruins

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- The Netherlands

- Palladianism

- Period Room

- Southern Italy

- Switzerland

Artist or Maker

- Adam, Robert

- Batoni, Pompeo

- Cozens, John Robert

- Desprez, Louis Jean

- Mengs, Anton Raphael

- Natoire, Charles Joseph

- Panini, Giovanni Paolo

- Permoser, Balthasar

- Piranesi, Francesco

- Piranesi, Giovanni Battista

- Rigaud, Jacques

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Domenico

- Wedgwood, Josiah

- Wilson, Richard

Online Features

- Connections: “Flux” by Annie Labatt

- Connections: “Genoa” by Xavier Salomon

Encyclopedia of Tourism pp 1–2 Cite as

The Grand Tour

- Kathryn Walchester 3

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 28 November 2023

The Grand Tour was primarily an educative tour of the European continent taken by young aristocratic Englishmen (Hibbert, 1969 ,13-25; Black, 1992 ). The first use of the term in English was used in a guide book. It highlighted the tour which included the classical cities of Rome and Naples, visited so as to underpin the conventional education in the classics undertaken by young men from the British upper classes. It followed a standard route and often included Paris and cities in Germany, and the Belgian resort of Spa (Lassells 1698: 24).

The young tourists would often be accompanied by their tutor or “bear leader,” who both acted as guide, teacher, and chaperon. This latter function was particularly significant given that foreign travels by rich young men soon attracted an array of licentious opportunities, including drinking, gambling, and sexual experimentation, facilitated by enterprising locals (Hibbert, 1969 , 15-6). As a result, the young Grand Tourists gained a negative...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Black, J. 1992. The British abroad: The grand tour in the eighteenth century . Stroud: Sutton.

Google Scholar

Hibbert, C. 1969. The grand tour . London: Hamlyn.

Seaton, A.V. 2019. Grand tour. In Keywords for Travel Writing Studies , 108–110. London: Anthem.

Towner, J. 1985. The grand tour: A key phase in the history of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 12: 297–333.

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK

Kathryn Walchester

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kathryn Walchester .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Hospitality Leadership, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, WI, USA

Jafar Jafari

School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

Honggen Xiao

Section Editor information

Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

Yoel Mansfeld Ph.D

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Walchester, K. (2023). The Grand Tour. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_904-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_904-1

Received : 07 March 2022

Accepted : 23 March 2023

Published : 28 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The lavish Grand Tours of history — and how they shaped the way we travel today

It was a rite of passage for young, upper-class Englishmen with virtually unlimited money to burn — a hedonistic "Grand Tour" far from home, unfolding over two or three or even four years.

Designed to teach them about art, history and culture, it was a kind of finishing school that would ready them for life in the powerful ruling elite.

Unsurprisingly, sex, gambling, drinking, and lavish parties also found their way into the mix.

For many historians, these travellers of the 17th and 18th centuries represent the first modern tourists.

They fuelled a passion for adventure and paved the way for the type of travel we know (and miss) today.

The ultimate destinations

The Grand Tour began in about 1660 and reached its zenith between 1748 and 1789.

It was typically undertaken by men aged between 18 and 25 — the sons of the aristocracy.

First, they braved the English Channel to reach Belgium or France. There, many purchased a carriage for the onward journey.

They were accompanied by a guide, known as a "bear-leader", who tutored them in art, music, literature and history.

If they were wealthy enough, their entourage included a troop of servants.

While there was no fixed route, most tours included the great cities of Europe — Paris, Geneva, Berlin — and a lengthy sojourn in Italy.

"A man who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see," English author Samuel Johnson remarked in 1776.

Rome was considered the ultimate destination, but Venice, Florence, Milan and Naples were also high on the list.

A drive for education and enlightenment was at the heart of the tour.

The Grand Tourists looked at art, admired monuments, visited historical sites, and studied classical architecture. They mingled with the elite social classes.

Behaving badly

They were students with practically unlimited budgets, and often very little supervision.

European history expert Eric Zuelow says this meant they were "apt to behave in a rather different way with rather different interests than the Grand Tour was designed to instil in them".

"So what they tended to do was to go and drink a lot, to gamble, to frequent [sex workers]," he tells ABC RN's Rear Vision .

"They tended not to learn much in the way of languages, not to learn much in the way of culture, but to have a lot of fun.

"And that created, I would argue, really one of the first instances of the notion of tourists as being lesser creatures and travellers being something much better.

"The first tourists, the Grand Tourists, did not behave all that well. And tourists have held that stigma ever since."

It wasn ' t all smooth sailing

In the days of the Grand Tour, travel wasn't for the faint-hearted.

There are many reports of the young men becoming ill from travel sickness, rough seas and foreign foods.

Disease was another threat — during his Grand Tour, writer John Evelyn nearly died of smallpox in Geneva.

Thieves were highly active, so many Grand Tourists didn't carry cash, instead taking the equivalent of travellers' cheques.

Roads were rough and full of potholes, and the carriages could only journey about 20 kilometres a day. Some parts of the trip were undertaken by foot.

"So they could be weeks just getting from one place to another," says historian Susan Barton.

Crossing the Alps was a particular challenge.

Some Grand Tourists hired a sedan chair to be carried, literally, over the mountain passes.

The "chairmen of Mont Cenis" became known throughout the Alps for their strength and dexterity.

The rise of 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption'

These early travellers carried guidebooks, which advised them of what to see, hear and do.

They were told to show their wealth at every turn, to garner respect.

As time went by, those making the Grand Tour also became shoppers. They wanted to buy things they could later show off.

"What was happening at this time was a development of what one scholar called 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption', which is a really fancy term for spending money because buying things will make you better," Professor Zuelow says.

"The Grand Tour, with its original educational roots, merged with that self-illusory, hedonistic idea, creating a consumable."

The young tourists would return to England with bulging luggage — marble statues from Rome, colourful glassware from Venice, pumice stone from Naples.

They brought back paintings depicting the Colosseum in Rome, the canals in Venice, the Parthenon in Athens.

They'd also commission portraits of themselves, and a mini industry sprung up around this.

It wasn't just to remind themselves of all they had seen and done. It was so other people would also know.

The souvenirs were displayed with great pride in the family's estates and manor houses.

"And later some of those things ended up in museums," Dr Barton says.

"So in a way they were creating the future 20th century tourism where people were visiting country houses as part of their leisure."

Not all Britons — and not all men

Although Britons far outnumbered all others, Professor Zuelow notes that they weren't the only Grand Tourists.

Peter the Great, the Russian Tsar, famously made the trip, as did German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and King Gustav III of Sweden.

And it also wasn't just men.

Professor Zuelow says English women such as author Mary Wollstonecraft and socialite Lady Mary Wortley Montagu spent extensive time in Europe, enjoying new freedoms and the chance for an education not available to them back home.

Travel for leisure and the Grand Tour's legacy

By 1815, the Grand Tour was disappearing.

Professor Zuelow says part of the reason for this is obvious: the French Revolution, followed closely by the Napoleonic Wars, swept across Europe starting in 1789 and extended until 1815.

"When the fighting stopped, many visitors returned — even if only to see the damages of war — but this was no longer the old Grand Tour," he writes in his book, A History of Modern Travel.

After 1815, travel to Europe slowly opened up for much wider social groups.

"So rather than just the aristocracy, we've got middle class people starting to travel, but it was still quite a lengthy process," Dr Barton says.

The legacy of the Grand Tour lives on to this day.

It still influences the destinations we visit, and has shaped the ideas of culture and sophistication that surround the act of travel.

It shaped the notion that there's something to be gained from venturing overseas, that there's a lot on offer if you can leave home to find it.

"Prior to the Grand Tour, there wasn't a lot of travel for leisure," Professor Zuelow says.

"Medieval pilgrims have been put forward as possible tourists but they were travelling for religious purposes. And although they had a lot of fun along the way, it really was about getting into Heaven."

Many of the Grand Tourists wrote about their adventures, fuelling a new level of wanderlust in society.

The trips were the stuff of fantasy, and others wanted to follow.

It was a first step in the direction of mass tourism, and the kind of travel we know today.

"I define it really as travelling for the purpose of travelling, travelling for fun, travelling for enjoyment, feeling that travel is going to make you healthier and happier and a better person," Professor Zuelow says.

To hear more about the history of travel, the impact of technology on tourism, and the future may hold, listen to ABC Radio National's Rear Vision podcast .

RN in your inbox

Get more stories that go beyond the news cycle with our weekly newsletter.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Pay with a credit card, and other tips to covid-proof your next holiday.

It's so bad Qantas is selling its pyjamas — but flying's new reality is not as grim

Guide Alice and the 'sleeping buffalo' that stole her heart

- Community and Society

- European Union

- Human Interest

- Lifestyle and Leisure

- Travel and Tourism (Lifestyle and Leisure)

- United Kingdom

- United States

The Grand Tour

Englishmen abroad.

At its height, from around 1660–1820, the Grand Tour was considered to be the best way to complete a gentleman’s education. After leaving school or university, young noblemen from northern Europe left for France to start the tour.

After acquiring a coach in Calais, they would ride on to Paris – their first major stop. From there they would head south to Italy or Spain, carting all their possessions and servants with them.

Their most popular destinations were the great towns and cities of the Renaissance, along with the remains of ancient Roman and Greek civilisation.

Their souvenirs were rather more durable than holiday snaps, replica Eiffel Towers or t-shirts – they filled crates with paintings, sculptures and fine clothes.

Travel was somewhat more of an ordeal than today (even accounting for the worst airport queues and hold-ups). However rich these young men were, there was no hot shower after a day on the road, no credit card to get them out of a tight spot, and no mobile phone to ring people for help.

Furthermore transport was slow. Instead of taking a 12-month trip, some went away for many years. Most went for at least two, spending months in essential spots along the way.

The plan was to set young noblemen up to manage their estates, furnish their houses and prepare for conversation in polite society. But did the Grand Tour turn them into gentlemen? Sometimes a taste for vice got in the way.

Next: A moral education

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

Travelling for culture: the Grand Tour

Introduction.

In the eighteenth century and into the early part of the nineteenth, considerable numbers of aristocratic men (and sometimes women) travelled across Europe in pursuit of education, social advancement and entertainment, on what was known as the Grand Tour. A central objective was to gain exposure to the cultures of classical antiquity , particularly ancient Greece and Rome, and particularly in Italy. Today, the Grand Tour is an interesting object of study because of what it can tell us about how different cultures encountered one another. We can ask why the ancient world held such fascination for elite European culture at this time, for example, and explore how visitors conveyed that fascination through art and literature. We can also ask how the experience of other groups, such as women and children, might have compared to those of the typical male Grand Tourist.

In this free course, you’ll have the opportunity to explore some of these questions, and to gain an introduction to the Grand Tour. The course also provides a snapshot of how our study of this historical and cultural phenomenon can be conducted through different disciplines in the Arts and Humanities, with each section of the course tackling the Grand Tour from a different perspective. In the first, Classical Studies, you will find a short introduction to one of the most iconic destinations of the Grand Tour, the Colosseum in Rome, because a good understanding of the historical and cultural significance of such monuments is an important foundation for studying later responses to them. Sections on Art History and English Literature will show you how portrait painting and poetry provided different ways of recording the encounters with Rome that took place on the Grand Tour, before a final section, Creative Writing, shows how such paintings and poetry can act as triggers or sources of inspiration for later writers too, leading to more imaginative engagements with elements of the Grand Tour.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A112 Cultures [ Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. ( Hide tip ) ] .

Taken together, these sections offer a multifaceted perspective on the Grand Tour, and give you some insight into the study of different disciplines that you might undertake if you were to study A112.

This website uses cookies

We place some essential cookies on your device to make this website work. We'd like to use additional cookies to remember your settings and understand how you use our services. This information will help us make improvements to the website.

COPY 1/209 (362e) ‘When Mother Travels’ Tom Browne

Lesson at a glance

Activity ideas.

Do you know anyone who has spent time travelling abroad?

Sometimes older students finish school and save up money to go abroad. They might travel from place to place, looking for paid work as they go. It is an adventure. The idea is to experience new sights, cultures and people – and to learn about the world in a hands-on way rather than in school.

This tradition dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries, when it became very fashionable for wealthy young men (and later women too) to take the ‘Grand Tour’. At school, they would have learned about ancient French literature, Italian art and Greek philosophy from books.

The Grand Tour encouraged students to travel to France, Italy or to Greece to see these things for themselves – to view the original paintings and to walk around famous buildings they had only seen images of in books before.

The very rich could afford to travel in horse-drawn carriages, and sometimes they might even have paid someone to carry them if the paths were too narrow. Only the very rich could afford the luxury of travel for fun, although the coming of the railways did bring the costs down a little towards the end of the 19th century.

Look at document WO 78/419 (27). This map of Italy was drawn in the mid-1700s. Italy was the most popular destination on the Grand Tour.

- Can you find the following places Holy days – very popular with visitors on the Grand Tour? Rome Venice Florence Naples

- If you were to visit Italy, which places would you want to visit and why?

- Look at the drawings on the bottom left of the map. Describe what is happening in each drawing. Can you name the volcano? Why might these drawings have been included on the map?

Look at document COPY 1/497.

- Describe the scene in this photograph.

- What are the people looking at? What is the photographer looking at?

- Are there any clues to help us date this photograph?

The photograph was taken in 1906 from the railway station of Pompeii in Italy. It shows tourists watching Vesuvius erupting. Pompeii had been an ancient Roman city, and a popular summer holiday destination for rich Romans. Fruits and vines grew well in the dark rich earth there. In AD 79, Vesuvius famously erupted killing many of the residents of this city and burying the buildings under layers of ash. There were many further eruptions (including the major eruption of 1631 depicted in the map you looked at earlier). From the mid 18th century, the lost city of Pompeii began to be excavated and became a very popular tourist destination. People loved the idea of travelling back in time and seeing what a Roman city looked like. Railways made it possible for more people to visit historic sites such as Pompeii because travel was cheaper than by horse and carriage.

- Why do you think Pompeii has attracted so many tourists over the years?

- Have you ever visited a historic site? What did you like about it? What did you learn about it? How was it different from just reading about it in a book or on the internet?

Look at document COPY 1/209 (362e). During the 18th and early 19th centuries tourists abroad would travel by horse and carriage. Roads were in such bad condition that journeys were difficult and long as well as dangerous. Once a traveller arrived at their destination they tended to want to stay there for some time before making the return journey. This meant that travellers had to bring clothes for all weathers, food and drink to last the journey as well as books and games for relaxation.

- How many suitcases and packages can you find?

- What sorts of things do you think this lady might have packed for her journey?

- The more luggage people took, the more expensive the journey. If you had to choose only 10 items to take on your long journey, what would they be? Could you fit them all in one bag?

Look at document COPY 1/221 (247). Thomas Cook started his travel agency business in 1841. At first, he booked trains to take people out for day trips around Britain. Later when his son took over the family business, Thomas Cook & Son offered tours around Europe too. People liked the idea of having someone to help them have a good holiday- booking tickets, making sure they caught the right train and giving advice on where to eat and what to do.

- Can you work out who is on holiday and who is the tour guide?

- Look carefully at the poster. What sort of people could go on a Thomas Cook escorted holiday?

- What do you think the people are looking at? What do you think they are saying?

- Tourists on the Grand Tour loved finding a great view! They loved trying to capture beautiful scenery or buildings through painting and later photography. Find your favourite view and paint or photograph it. Use the painting/photo to create a postcard and send someone a home- made postcard telling them a bit about this view.

- Plan your own ‘Grand Tour’ around where you live. Which destinations would you choose? What would be the highlights? Are there any great views, buildings, interesting historical sites near you, that could be included? Perhaps you could create your own travel agency like Thomas Cook did and offer escorted tours of your local area to your family?

The Grand Tour: Everything You Need to Know

Gokce Dyson 28 November 2022 min Read

Carl Spitzweg, Englishmen in Campania , ca. 1835, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Recommended

Art Travels

On the Road: Best Traveling Paintings

Artists’ Beloved Travel Destinations as Seen Through Their Art

How to Do a 21st-Century Grand Tour According to Mr. Bacchus

Nowadays, it is very common to take a gap year before or after university studies to travel and expand your horizons. Dedicating a year or two before committing to a full-time job means you can experience different cultures, learn languages, and enjoy having a bit of fun before settling down. Back in the day, with similar objectives, many noblemen embarked on a journey across Europe before entering adulthood. It was called the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour evolved between the 17th and 18th centuries as a custom of a traditional trip. The purpose of the Grand Tour was to provide male members of upper-class families with a formative experience. The term was first used by the Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassels in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy . The book came out in 1670 and described young lords traveling to Italy to see art, architecture, and antiquity. Lassels completed the Grand Tour five times during his lifetime.

In England, for example, the general view held by the aristocrats was that foreign travel completed the education of an English gentleman. However, some people were also quite skeptical about the tour. They feared the amount of money spent to make the Grand Tour possible could ruin the young nobility.

Although the Grand Tour was largely associated with English travelers, they were far from being the only ones on the road. On the contrary, wealthy families in France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark also saw traveling as an ideal way to finish the education of their societies’ future leaders.

Itinerary of the Grand Tour

The traditional route of the Grand Tour usually began in Dover, England. Grand tourists would cross the English Channel to Le Havre in France. Upon arrival in Paris , the young men tended to hire a French-speaking guide as French was the dominant language of the elite during the 17th and 18th centuries. In Paris, they spent some time taking lessons in fencing, riding, and perhaps dancing. There, they became accustomed to the sophisticated manners of French society in courtly behavior and fashion. Paris was a crucial step in preparing for their positions to be fulfilled in government or diplomacy waiting back in England.

From there, tourists would buy transport, and if they were prosperous enough, they would hire a tutor to accompany them. The travelers would then get back on the road and cross the Alps, carried in a chair at Mont Cenis before moving on to Turin.

Italy was exceedingly the most traveled country on the Grand Tour. A Grand tourist’s list of must-see cities in Italy included Florence , Venice , and Naples . And then, there was Rome . Each Italian city offered immense importance in experiencing art and architecture, and Rome had it all.

Touring Italy

Once arriving in Italy, noblemen traveled to Florence followed by Venice, Rome, and Naples. Florence was popular for its Renaissance art, magnificent country villas, and beautiful gardens. Young aristocrats were able to gain entry to private collections where they could observe the legacy of the Medici family. Venice , on the other hand, was the party city. There was, however, a second reason to visit Venice. During their travels, grand tourists often commissioned art to take back home with them. Wealthy ones brought sketch artists along with them. Others purchased ready-made artworks instead. Giovanni Battista Piranesi created numerous prints and sketches depicting the ancient ruins in Rome. The works of the Venetian artist were popular among noblemen.

Rome was considered the ultimate stop during the Grand Tour. The city had a harmonious mixture of past and present. One could experience modern-day Baroque art and architecture and ancient ruins , dating back thousands of years at the same time. It was lauded as home to Michelangelo’s and Bernini’s most prized works. Gentlemen visited spots like the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and Porta del Popolo. William Beckford described his feelings in a letter when he was on his Grand Tour:

Shall I ever forget the sensations I experienced upon slowly descending the hills, and crossing the bridge over the Tiber; when I entered an avenue between terraces and ornamented gates of villas, which leads to the Porto del Popolo… William Beckford, letter from the Grand Tour, 1780.

The next stop on the route was Naples. When Italian authorities began excavations in Herculaneum and Pompeii in the 1730s, grand tourists flocked there to delve into the mysteries of the ancient past. Naples became a popular retreat for the British who wanted to enjoy the coastal sun. Travelers such as J. W. Goethe praised the city’s glories:

Naples is a Paradise: everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognize. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now. J. W. Goethe, Google Arts& Culture .

Returning home, young gentlemen crossed the Alps to the German-speaking parts of Europe and visited Innsbruck, Vienna , Dresden, and Berlin . From there, they stopped in Holland and Flanders before returning to England.

With the introduction of steam railways in Europe around 1825, travel became safer, cheaper, and easier to undertake. The Grand Tour custom continued; however, it was not limited to the members of wealthy families. During the 19th century, many educated men had undertaken the Grand Tour. It also became more popular for women to travel across Europe with chaperones. A Room with A View, written by English novelist E. M. Forster, tells the story of a young woman who embarks on a journey to Italy in the 1900s.

Legacy of the Grand Tour

Grand tourists would return with crates full of books, oil paintings, medals, coins, and antique artifacts to be displayed in libraries, cabinets, drawing rooms, and galleries built for that purpose. The marble sarcophagus shown above was brought back from Italy to England by the third duke of Beaufort who found this item during his Grand Tour stop in Pompeii. Impressed by the European art academies on his Grand Tour, Joshua Reynolds founded the Royal Academy of Arts in London upon his return in 1768. The Grand Tour inspired many travelers to take a greater interest in ancient art. The British School in Rome was established to learn more about the Roman ruins and it still exists today.

Get your daily dose of art

Click and follow us on Google News to stay updated all the time

We love art history and writing about it. Your support helps us to sustain DailyArt Magazine and keep it running.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!

Gokce Dyson

Based in Canterbury, Gokce holds a bachelor's degree in History and Archaeological Studies and a master's degree in Museum and Gallery Studies. She firmly believes that art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time. If Gokce is not tucked into a cosy corner with a medieval history book, she can be found spending her evenings doing jigsaw puzzles.

Art Travels: Golden Temple of Amritsar

Nestled in the city of Amritsar in Northwestern India is the iconic Harmandir Sahib or Darbar Sahib, better known as the Golden Temple. This sublime...

Maya M. Tola 8 January 2024

Art and Sports: En Route to the Paris 2024 Olympics

The forthcoming Paris 2024 Summer Olympics will bridge the worlds of art and sport, with equestrian competitions at the Palace of Versailles, fencing...

Ledys Chemin 5 February 2024

10 Masterpieces You Need To See in London

London is a city full of masterpieces. It is not only one of the biggest art hubs but also one of the most multicultural places in the entire world.

Sandra Juszczyk 23 February 2024

The Qutub Complex: Architecture of the Early Islamic Period in India

The Qutub Minar complex is a collection of architectural marvels located at the Mehrauli Archaeological Park in New Delhi, India. The complex...

Maya M. Tola 8 October 2023

Never miss DailyArt Magazine's stories. Sign up and get your dose of art history delivered straight to your inbox!

The Educated Traveller

History of the grand tour .

In the early years of the 18th and 19th centuries it was fashionable, for wealthy British families, to send their son and heir on a tour of Europe. A trip that was designed to introduce the young ‘ milord ‘ to the art, history and culture of Italy. The British educational system was based on Latin and Greek literature and philosophy. An educated person was taught the classics from a very early age. Whilst the original Grand Tourists were mostly male, there were a few enlightened families who sent their daughters to ‘the continent’ too. Aristocratic families regarded this journey to Europe as an opportunity to complete their education. The journey was known as the ‘Grand Tour’. The young gentlemen and a few ladies were often accompanied by a ‘learned guide’ a person who could act as a tutor and chaperone. These guides, usually highly educated, were known in Italian as ‘ cicerone’ and it was their job to explain the history, art and literature of Italy to their young charges.

A ‘Grand Tour’ generally included visits to Rome, Naples, Venice and Florence. On the journey south Geneva or Montreux in Switzerland were popular stopping off points too. Think Daisy Miller in Henry James novella of the same name. Wealthy families traversed Europe, often for months on end, absorbing every possible palace, party and picnic in the process. For many it was a very long and decadent party for others it was a necessary departure from their homeland until the dust of a divorce, bankruptcy or other social scandal had settled.

THE JOURNEY – Young gentlemen would make the journey south from The British Isles, either by ship or overland by horse and carriage. There are numerous reports of these young travellers being made chronically ill by travel sickness, rough seas and ‘foreign food’. In the 1730s and 1740s roads were rough and full of potholes, carriages could expect to cover a maximum of 15-20 miles per day. Highwaymen and groups of brigands often preyed on travellers, hoping to steal money and jewels. In the days of the ‘Grand Tour’ travel wasn’t for the faint-hearted . Crossing the Alps was a particular challenge. Depending on the age and level of fitness of travellers, it may have been necessary to hire a sedan chair to be carried, literally, by strong local men over various Alpine passes. In fact the ‘chairmen of Mont Cenis’ close to Val d’Isere were known throughout the Alps for their strength and dexterity. These ‘chair carriers’ worked in pairs and groups of four, six or even eight men – they physically carried the ‘Grand Tourists’ over the Alps.

TRAVELLING – Having endured a crossing of the Alps the young ‘milordi’ would head to Milan or Turin where the local British consulate would offer a warm welcome. However, the really attractive destinations were further away, particularly Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples. These cities were renowned for their entertainment, lavish parties and sense of fun. There’s a fantastic cartoon, by David Allen (above) showing a young aristocrat arriving in Piazza di Spagna, Rome. His carriage is instantly surrounded by local touts, street performers, actors and actresses, all anxious to separate young ‘Algernon’ from his trunk full of cash! It’s interesting to remember that the Italians have been welcoming tourists to their lands for centuries. They’ve learned a thing or two about helping newly arrived foreigners!

VENICE – In Venice the British Consul Joseph Smith was an art collector and supporter of local artists. Smith lived in a small palace on the Grand Canal, filled with paintings, art, books and coins. He was patron of Canaletto, probably the most famous and popular Venetian painter of his day. Canaletto painted ‘vedute’ scenes of Venice. Every Grand Tourist wanted to leave with a Canaletto painting as a souvenir of the Grand Tour. Smith’s art collection was so impressive that a young King George III purchased the entire collection in 1762, when he was himself on the Grand Tour. So Joseph Smith’s art collection became the basis of the British ‘Royal Collection’ of art much of which can still be seen at Buckingham Palace or in the National Gallery, London today. Whilst in Venice the young Grand Tourists would attend concerts, visit churches and wherever possible attend a ball or two. Venice at Carnival time was a particular fascination – an opportunity to put on a mask and be whoever you wanted to be!

A typical Grand Tour of Europe could last up to two years and would always include several months staying in each city visited.

Florence was popular for its renaissance art, magnificent country villas and gardens, whilst Rome was essential for proper, classical, ancient ruins. Venice was the party city, especially at the time of Carnival. Naples was regarded as the home of archaeology, excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum began in the 1730s and Vesuvius was quite active at this time. Plumes of volcanic gases and occasional lava flows would illuminate the mountain after dark. The Grand Tourists would position themselves on the lower slopes of the volcano to watch the nightly spectacle.

IN ROME – many of the Grand Tourists funded excavation work in and around the Roman Forum and the Colosseum. Many of the Grand Tourists wanted to acquire a Roman statue or sculpture to take home as a souvenir. There were numerous stonemasons working in and around the basement of the Colosseum, creating modern and ‘antique’ marble sculptures. Even in the 18th century demand exceeded supply in the ‘genuine Roman sculpture market’. Many Grand Tourists left for home with an ‘original’ antique Roman statue, which years later, under expert examination turned out to be a fake! The artist Panini painted several imaginary compositions of young Grand Tourists surrounded by paintings of Roman buildings and ruins. Each of the ‘ruins’ in the paintings was based on an actual Roman building. For example, in the painting below The Pantheon is clearly visible just to the right of the two standing gentlemen. Above the Pantheon is the Colosseum. On the left of the painting above the two seated gentlemen the Roman arches of Constantine and Septimius Severus can be seen.

Roma Antica – by Giovanni Paolo Pannini c. 1754 – Stuttgart Art Museum

The Grand Tour inspired many travellers to take a greater interest in Roman history and art. The study of archaeology was born at this time with extensive excavations taking place in Pompeii, Herculaneum and in the area of the Roman Forum in Rome. The British School at Rome was established to learn more about the Roman ruins and to fund excavations. The School still exists today. Below is another painting by Pannini showing the wonders of Modern Rome (1750s) – featuring details of Baroque fountains, palaces and elegant piazzas. These exceptionally detailed paintings effectively catalogue the ‘ancient marbles’ discovered in Italy by the middle years of the 18th century.

NAPLES – for fun and excitement on the Grand Tour was very popular. Lord Hamilton, British Ambassador in Naples was a wonderful host and put on spectacular parties and musical evenings. His second wife Emma Hamilton would dress in Roman and Greek style clothing and perform a series of ‘Attitudes’ where guests had to guess her identity. It was here at the Hamilton residence that Emma attracted the attention of Lord Nelson, British naval hero of the day, and they became lovers.

Meanwhile Vesuvius , the volcano that dominates the Bay of Naples was having an active phase in the 1760s and 1770s, most days steam could be seen rising from the crater and frequently, especially after nightfall, streams of glowing lava could be observed. Lord Hamilton wrote several articles on Vesuvius and the lava flows that he witnessed. Many visiting painters were inspired to paint Vesuvius and the surrounding area. The science of vulcanology was in its infancy. The spectacle that Vesuvius offered visitors most nights must have seemed quite extraordinary to the early Grand Tourists – typically away from home in strange and different lands for the first time.