- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture and the Environment

- Case Studies

- Chemistry and Toxicology

- Environment and Human Health

- Environmental Biology

- Environmental Economics

- Environmental Engineering

- Environmental Ethics and Philosophy

- Environmental History

- Environmental Issues and Problems

- Environmental Processes and Systems

- Environmental Sociology and Psychology

- Environments

- Framing Concepts in Environmental Science

- Management and Planning

- Policy, Governance, and Law

- Quantitative Analysis and Tools

- Sustainability and Solutions

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The role of tourism in sustainable development.

- Robert B. Richardson Robert B. Richardson Community Sustainability, Michigan State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.387

- Published online: 25 March 2021

Sustainable development is the foundational principle for enhancing human and economic development while maintaining the functional integrity of ecological and social systems that support regional economies. Tourism has played a critical role in sustainable development in many countries and regions around the world. In developing countries, tourism development has been used as an important strategy for increasing economic growth, alleviating poverty, creating jobs, and improving food security. Many developing countries are in regions that are characterized by high levels of biological diversity, natural resources, and cultural heritage sites that attract international tourists whose local purchases generate income and support employment and economic development. Tourism has been associated with the principles of sustainable development because of its potential to support environmental protection and livelihoods. However, the relationship between tourism and the environment is multifaceted, as some types of tourism have been associated with negative environmental impacts, many of which are borne by host communities.

The concept of sustainable tourism development emerged in contrast to mass tourism, which involves the participation of large numbers of people, often in structured or packaged tours. Mass tourism has been associated with economic leakage and dependence, along with negative environmental and social impacts. Sustainable tourism development has been promoted in various ways as a framing concept in contrast to these economic, environmental, and social impacts. Some literature has acknowledged a vagueness of the concept of sustainable tourism, which has been used to advocate for fundamentally different strategies for tourism development that may exacerbate existing conflicts between conservation and development paradigms. Tourism has played an important role in sustainable development in some countries through the development of alternative tourism models, including ecotourism, community-based tourism, pro-poor tourism, slow tourism, green tourism, and heritage tourism, among others that aim to enhance livelihoods, increase local economic growth, and provide for environmental protection. Although these models have been given significant attention among researchers, the extent of their implementation in tourism planning initiatives has been limited, superficial, or incomplete in many contexts.

The sustainability of tourism as a global system is disputed among scholars. Tourism is dependent on travel, and nearly all forms of transportation require the use of non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels for energy. The burning of fossil fuels for transportation generates emissions of greenhouse gases that contribute to global climate change, which is fundamentally unsustainable. Tourism is also vulnerable to both localized and global shocks. Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to localized shocks include the impacts of natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and civil unrest. Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to global shocks include the impacts of climate change, economic crisis, global public health pandemics, oil price shocks, and acts of terrorism. It is clear that tourism has contributed significantly to economic development globally, but its role in sustainable development is uncertain, debatable, and potentially contradictory.

- conservation

- economic development

- environmental impacts

- sustainable development

- sustainable tourism

- tourism development

Introduction

Sustainable development is the guiding principle for advancing human and economic development while maintaining the integrity of ecosystems and social systems on which the economy depends. It is also the foundation of the leading global framework for international cooperation—the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015 ). The concept of sustainable development is often associated with the publication of Our Common Future (World Commission on Environment and Development [WCED], 1987 , p. 29), which defined it as “paths of human progress that meet the needs and aspirations of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” Concerns about the environmental implications of economic development in lower income countries had been central to debates about development studies since the 1970s (Adams, 2009 ). The principles of sustainable development have come to dominate the development discourse, and the concept has become the primary development paradigm since the 1990s.

Tourism has played an increasingly important role in sustainable development since the 1990s, both globally and in particular countries and regions. For decades, tourism has been promoted as a low-impact, non-extractive option for economic development, particularly for developing countries (Gössling, 2000 ). Many developing countries have managed to increase their participation in the global economy through development of international tourism. Tourism development is increasingly viewed as an important tool in increasing economic growth, alleviating poverty, and improving food security. Tourism enables communities that are poor in material wealth, but rich in history and cultural heritage, to leverage their unique assets for economic development (Honey & Gilpin, 2009 ). More importantly, tourism offers an alternative to large-scale development projects, such as construction of dams, and to extractive industries such as mining and forestry, all of which contribute to emissions of pollutants and threaten biodiversity and the cultural values of Indigenous Peoples.

Environmental quality in destination areas is inextricably linked with tourism, as visiting natural areas and sightseeing are often the primary purpose of many leisure travels. Some forms of tourism, such as ecotourism, can contribute to the conservation of biodiversity and the protection of ecosystem functions in destination areas (Fennell, 2020 ; Gössling, 1999 ). Butler ( 1991 ) suggests that there is a kind of mutual dependence between tourism and the environment that should generate mutual benefits. Many developing countries are in regions that are characterized by high levels of species diversity, natural resources, and protected areas. Such ideas imply that tourism may be well aligned with the tenets of sustainable development.

However, the relationship between tourism and the environment is complex, as some forms of tourism have been associated with negative environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, land use, and food consumption (Butler, 1991 ; Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ; Hunter & Green, 1995 ; Vitousek et al., 1997 ). Assessments of the sustainability of tourism have highlighted several themes, including (a) parks, biodiversity, and conservation; (b) pollution and climate change; (c) prosperity, economic growth, and poverty alleviation; (d) peace, security, and safety; and (e) population stabilization and reduction (Buckley, 2012 ). From a global perspective, tourism contributes to (a) changes in land cover and land use; (b) energy use, (c) biotic exchange and extinction of wild species; (d) exchange and dispersion of diseases; and (e) changes in the perception and understanding of the environment (Gössling, 2002 ).

Research on tourism and the environment spans a wide range of social and natural science disciplines, and key contributions have been disseminated across many interdisciplinary fields, including biodiversity conservation, climate science, economics, and environmental science, among others (Buckley, 2011 ; Butler, 1991 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Lenzen et al., 2018 ). Given the global significance of the tourism sector and its environmental impacts, the role of tourism in sustainable development is an important topic of research in environmental science generally and in environmental economics and management specifically. Reviews of tourism research have highlighted future research priorities for sustainable development, including the role of tourism in the designation and expansion of protected areas; improvement in environmental accounting techniques that quantify environmental impacts; and the effects of individual perceptions of responsibility in addressing climate change (Buckley, 2012 ).

Tourism is one of the world’s largest industries, and it has linkages with many of the prime sectors of the global economy (Fennell, 2020 ). As a global economic sector, tourism represents one of the largest generators of wealth, and it is an important agent of economic growth and development (Garau-Vadell et al., 2018 ). Tourism is a critical industry in many local and national economies, and it represents a large and growing share of world trade (Hunter, 1995 ). Global tourism has had an average annual increase of 6.6% over the past half century, with international tourist arrivals rising sharply from 25.2 million in 1950 to more than 950 million in 2010 . In 2019 , the number of international tourists reached 1.5 billion, up 4% from 2018 (Fennell, 2020 ; United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2020 ). European countries are host to more than half of international tourists, but since 1990 , growth in international arrivals has risen faster than the global average, in both the Middle East and the Asia and Pacific region (UNWTO, 2020 ).

The growth in global tourism has been accompanied by an expansion of travel markets and a diversification of tourism destinations. In 1950 , the top five travel destinations were all countries in Europe and the Americas, and these destinations held 71% of the global travel market (Fennell, 2020 ). By 2002 , these countries represented only 35%, which underscores the emergence of newly accessible travel destinations in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Pacific Rim, including numerous developing countries. Over the past 70 years, global tourism has grown significantly as an economic sector, and it has contributed to the economic development of dozens of nations.

Given the growth of international tourism and its emergence as one of the world’s largest export sectors, the question of its impact on economic growth for the host countries has been a topic of great interest in the tourism literature. Two hypotheses have emerged regarding the role of tourism in the economic growth process (Apergis & Payne, 2012 ). First, tourism-led growth hypothesis relies on the assumption that tourism is an engine of growth that generates spillovers and positive externalities through economic linkages that will impact the overall economy. Second, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis emphasizes policies oriented toward well-defined and enforceable property rights, stable political institutions, and adequate investment in both physical and human capital to facilitate the development of the tourism sector. Studies have concluded with support for both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (e.g., Durbarry, 2004 ; Katircioglu, 2010 ) and the economic-led growth hypothesis (e.g., Katircioglu, 2009 ; Oh, 2005 ), whereas other studies have found support for a bidirectional causality for tourism and economic growth (e.g., Apergis & Payne, 2012 ; Lee & Chang, 2008 ).

The growth of tourism has been marked by an increase in the competition for tourist expenditures, making it difficult for destinations to maintain their share of the international tourism market (Butler, 1991 ). Tourism development is cyclical and subject to short-term cycles and overconsumption of resources. Butler ( 1980 ) developed a tourist-area cycle of evolution that depicts the number of tourists rising sharply over time through periods of exploration, involvement, and development, before eventual consolidation and stagnation. When tourism growth exceeds the carrying capacity of the area, resource degradation can lead to the decline of tourism unless specific steps are taken to promote rejuvenation (Butler, 1980 , 1991 ).

The potential of tourism development as a tool to contribute to environmental conservation, economic growth, and poverty reduction is derived from several unique characteristics of the tourism system (UNWTO, 2002 ). First, tourism represents an opportunity for economic diversification, particularly in marginal areas with few other export options. Tourists are attracted to remote areas with high values of cultural, wildlife, and landscape assets. The cultural and natural heritage of developing countries is frequently based on such assets, and tourism represents an opportunity for income generation through the preservation of heritage values. Tourism is the only export sector where the consumer travels to the exporting country, which provides opportunities for lower-income households to become exporters through the sale of goods and services to foreign tourists. Tourism is also labor intensive; it provides small-scale employment opportunities, which also helps to promote gender equity. Finally, there are numerous indirect benefits of tourism for people living in poverty, including increased market access for remote areas through the development of roads, infrastructure, and communication networks. Nevertheless, travel is highly income elastic and carbon intensive, which has significant implications for the sustainability of the tourism sector (Lenzen et al., 2018 ).

Concerns about environmental issues appeared in tourism research just as global awareness of the environmental impacts of human activities was expanding. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm in 1972 , the same year as the publication of The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al., 1972 ), which highlighted the concerns about the implications of exponential economic and population growth in a world of finite resources. This was the same year that the famous Blue Marble photograph of Earth was taken by the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft (Höhler, 2015 , p. 10), and the image captured the planet cloaked in the darkness of space and became a symbol of Earth’s fragility and vulnerability. As noted by Buckley ( 2012 ), tourism researchers turned their attention to social and environmental issues around the same time (Cohen, 1978 ; Farrell & McLellan, 1987 ; Turner & Ash, 1975 ; Young, 1973 ).

The notion of sustainable development is often associated with the publication of Our Common Future , the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, also known as the Brundtland Commission (WCED, 1987 ). The report characterized sustainable development in terms of meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987 , p. 43). Four basic principles are fundamental to the concept of sustainability: (a) the idea of holistic planning and strategy making; (b) the importance of preserving essential ecological processes; (c) the need to protect both human heritage and biodiversity; and (d) the need to develop in such a way that productivity can be sustained over the long term for future generations (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ). In addition to achieving balance between economic growth and the conservation of natural resources, there should be a balance of fairness and opportunity between the nations of the world.

Although the modern concept of sustainable development emerged with the publication of Our Common Future , sustainable development has its roots in ideas about sustainable forest management that were developed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries (Blewitt, 2015 ; Grober, 2007 ). Sustainable forest management is concerned with the stewardship and use of forests in a way that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, and regeneration capacity as well as their potential to fulfill society’s demands for forest products and benefits. Building on these ideas, Daly ( 1990 ) offered two operational principles of sustainable development. First, sustainable development implies that harvest rates should be no greater than rates of regeneration; this concept is known as maximum sustainable yield. Second, waste emission rates should not exceed the natural assimilative capacities of the ecosystems into which the wastes are emitted. Regenerative and assimilative capacities are characterized as natural capital, and a failure to maintain these capacities is not sustainable.

Shortly after the emergence of the concept of sustainable development in academic and policy discourse, tourism researchers began referring to the notion of sustainable tourism (May, 1991 ; Nash & Butler, 1990 ), which soon became the dominant paradigm of tourism development. The concept of sustainable tourism, as with the role of tourism in sustainable development, has been interpreted in different ways, and there is a lack of consensus concerning its meaning, objectives, and indicators (Sharpley, 2000 ). Growing interest in the subject inspired the creation of a new academic journal, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , which was launched in 1993 and has become a leading tourism journal. It is described as “an international journal that publishes research on tourism and sustainable development, including economic, social, cultural and political aspects.”

The notion of sustainable tourism development emerged in contrast to mass tourism, which is characterized by the participation of large numbers of people, often provided as structured or packaged tours. Mass tourism has risen sharply in the last half century. International arrivals alone have increased by an average annual rate of more than 25% since 1950 , and many of those trips involved mass tourism activities (Fennell, 2020 ; UNWTO, 2020 ). Some examples of mass tourism include beach resorts, cruise ship tourism, gaming casinos, golf resorts, group tours, ski resorts, theme parks, and wildlife safari tourism, among others. Little data exist regarding the volume of domestic mass tourism, but nevertheless mass tourism activities dominate the global tourism sector. Mass tourism has been shown to generate benefits to host countries, such as income and employment generation, although it has also been associated with economic leakage (where revenue generated by tourism is lost to other countries’ economies) and economic dependency (where developing countries are dependent on wealthier countries for tourists, imports, and foreign investment) (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Khan, 1997 ; Peeters, 2012 ). Mass tourism has been associated with numerous negative environmental impacts and social impacts (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Fennell, 2020 ; Ghimire, 2013 ; Gursoy et al., 2010 ; Liu, 2003 ; Peeters, 2012 ; Wheeller, 2007 ). Sustainable tourism development has been promoted in various ways as a framing concept in contrast to many of these economic, environmental, and social impacts.

Much of the early research on sustainable tourism focused on defining the concept, which has been the subject of vigorous debate (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Inskeep, 1991 ; Liu, 2003 ; Sharpley, 2000 ). Early definitions of sustainable tourism development seemed to fall in one of two categories (Sharpley, 2000 ). First, the “tourism-centric” paradigm of sustainable tourism development focuses on sustaining tourism as an economic activity (Hunter, 1995 ). Second, alternative paradigms have situated sustainable tourism in the context of wider sustainable development policies (Butler, 1991 ). One of the most comprehensive definitions of sustainable tourism echoes some of the language of the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainable development (WCED, 1987 ), emphasizing opportunities for the future while also integrating social and environmental concerns:

Sustainable tourism can be thought of as meeting the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunity for the future. Sustainable tourism development is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that we can fulfill economic, social and aesthetic needs while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems. (Inskeep, 1991 , p. 461)

Hunter argued that over the short and long terms, sustainable tourism development should

“meet the needs and wants of the local host community in terms of improved living standards and quality of life;

satisfy the demands of tourists and the tourism industry, and continue to attract them in order to meet the first aim; and

safeguard the environmental resource base for tourism, encompassing natural, built and cultural components, in order to achieve both of the preceding aims.” (Hunter, 1995 , p. 156)

Numerous other definitions have been documented, and the term itself has been subject to widespread critique (Buckley, 2012 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ). Nevertheless, there have been numerous calls to move beyond debate about a definition and to consider how it may best be implemented in practice (Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Liu, 2003 ). Cater ( 1993 ) identified three key criteria for sustainable tourism: (a) meeting the needs of the host population in terms of improved living standards both in the short and long terms; (b) satisfying the demands of a growing number of tourists; and (c) safeguarding the natural environment in order to achieve both of the preceding aims.

Some literature has acknowledged a vagueness of the concept of sustainable tourism, which has been used to advocate for fundamentally different strategies for tourism development that may exacerbate existing conflicts between conservation and development paradigms (Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ; McKercher, 1993b ). Similar criticisms have been leveled at the concept of sustainable development, which has been described as an oxymoron with a wide range of meanings (Adams, 2009 ; Daly, 1990 ) and “defined in such a way as to be either morally repugnant or logically redundant” (Beckerman, 1994 , p. 192). Sharpley ( 2000 ) suggests that in the tourism literature, there has been “a consistent and fundamental failure to build a theoretical link between sustainable tourism and its parental paradigm,” sustainable development (p. 2). Hunter ( 1995 ) suggests that practical measures designed to operationalize sustainable tourism fail to address many of the critical issues that are central to the concept of sustainable development generally and may even actually counteract the fundamental requirements of sustainable development. He suggests that mainstream sustainable tourism development is concerned with protecting the immediate resource base that will sustain tourism development while ignoring concerns for the status of the wider tourism resource base, such as potential problems associated with air pollution, congestion, introduction of invasive species, and declining oil reserves. The dominant paradigm of sustainable tourism development has been described as introverted, tourism-centric, and in competition with other sectors for scarce resources (McKercher, 1993a ). Hunter ( 1995 , p. 156) proposes an alternative, “extraparochial” paradigm where sustainable tourism development is reconceptualized in terms of its contribution to overall sustainable development. Such a paradigm would reconsider the scope, scale, and sectoral context of tourism-related resource utilization issues.

“Sustainability,” “sustainable tourism,” and “sustainable development” are all well-established terms that have often been used loosely and interchangeably in the tourism literature (Liu, 2003 ). Nevertheless, the subject of sustainable tourism has been given considerable attention and has been the focus of numerous academic compilations and textbooks (Coccossis & Nijkamp, 1995 ; Hall & Lew, 1998 ; Stabler, 1997 ; Swarbrooke, 1999 ), and it calls for new approaches to sustainable tourism development (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Sharpley, 2000 ). The notion of sustainable tourism has been reconceptualized in the literature by several authors who provided alternative frameworks for tourism development (Buckley, 2012 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ; McKercher, 1993b ; Sharpley, 2000 ).

Early research in sustainable tourism focused on the local environmental impacts of tourism, including energy use, water use, food consumption, and change in land use (Buckley, 2012 ; Butler, 1991 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Hunter & Green, 1995 ). Subsequent research has emphasized the global environmental impacts of tourism, such as greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity losses (Gössling, 2002 ; Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ; Lenzen et al., 2018 ). Additional research has emphasized the impacts of environmental change on tourism itself, including the impacts of climate change on tourist behavior (Gössling et al., 2012 ; Richardson & Loomis, 2004 ; Scott et al., 2012 ; Viner, 2006 ). Countries that are dependent on tourism for economic growth may be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (Richardson & Witkoswki, 2010 ).

The early focus on environmental issues in sustainable tourism has been broadened to include economic, social, and cultural issues as well as questions of power and equity in society (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Sharpley, 2014 ), and some of these frameworks have integrated notions of social equity, prosperity, and cultural heritage values. Sustainable tourism is dependent on critical long-term considerations of the impacts; notions of equity; an appreciation of the importance of linkages (i.e., economic, social, and environmental); and the facilitation of cooperation and collaboration between different stakeholders (Elliott & Neirotti, 2008 ).

McKercher ( 1993b ) notes that tourism resources are typically part of the public domain or are intrinsically linked to the social fabric of the host community. As a result, many commonplace tourist activities such as sightseeing may be perceived as invasive by members of the host community. Many social impacts of tourism can be linked to the overuse of the resource base, increases in traffic congestion, rising land prices, urban sprawl, and changes in the social structure of host communities. Given the importance of tourist–resident interaction, sustainable tourism development depends in part on the support of the host community (Garau-Vadell et al., 2018 ).

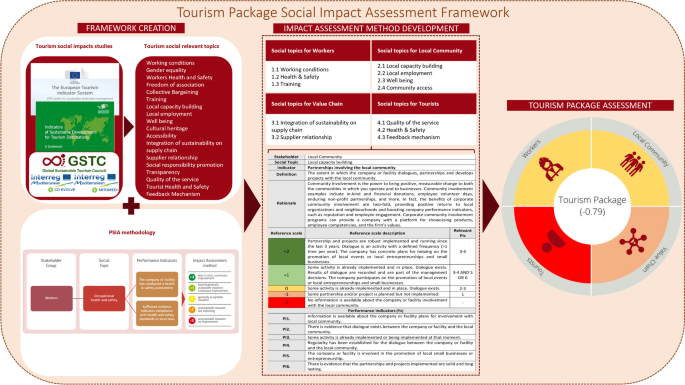

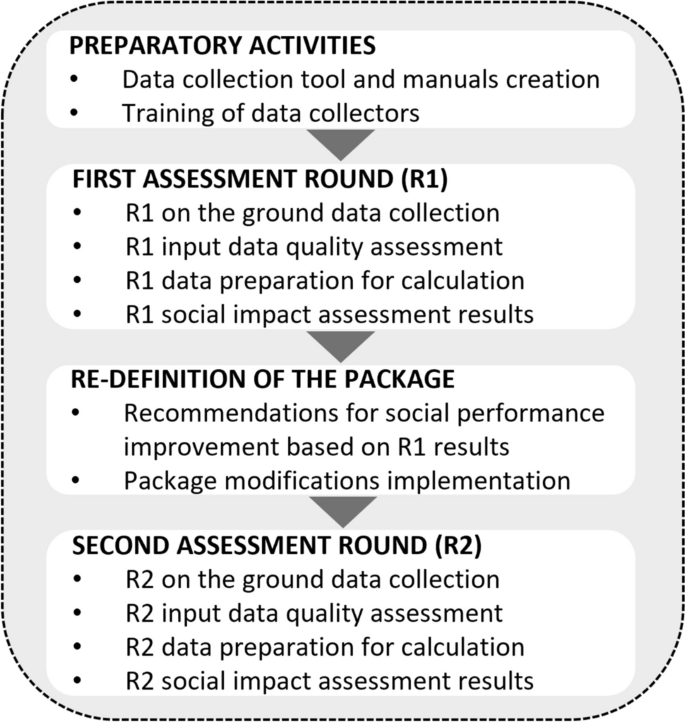

Tourism planning involves the dual objectives of optimizing the well-being of local residents in host communities and minimizing the costs of tourism development (Sharpley, 2014 ). Tourism researchers have paid significant attention to examining the social impacts of tourism in general and to understanding host communities’ perceptions of tourism in particular. Studies of the social impacts of tourism development have examined the perceptions of local residents and the effects of tourism on social cohesion, traditional lifestyles, and the erosion of cultural heritage, particularly among Indigenous Peoples (Butler & Hinch, 2007 ; Deery et al., 2012 ; Mathieson & Wall, 1982 ; Sharpley, 2014 ; Whitford & Ruhanen, 2016 ).

Alternative Tourism and Sustainable Development

A wide body of published research is related to the role of tourism in sustainable development, and much of the literature involves case studies of particular types of tourism. Many such studies contrast types of alternative tourism with those of mass tourism, which has received sustained criticism for decades and is widely considered to be unsustainable (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Fennell, 2020 ; Gursoy et al., 2010 ; Liu, 2003 ; Peeters, 2012 ; Zapata et al., 2011 ). Still, some tourism researchers have taken issue with the conclusion that mass tourism is inherently unsustainable (Sharpley, 2000 ; Weaver, 2007 ), and some have argued for developing pathways to “sustainable mass tourism” as “the desired and impending outcome for most destinations” (Weaver, 2012 , p. 1030). In integrating an ethical component to mass tourism development, Weaver ( 2014 , p. 131) suggests that the desirable outcome is “enlightened mass tourism.” Such suggestions have been contested in the literature and criticized for dubious assumptions about emergent norms of sustainability and support for growth, which are widely seen as contradictory (Peeters, 2012 ; Wheeller, 2007 ).

Models of responsible or alternative tourism development include ecotourism, community-based tourism, pro-poor tourism, slow tourism, green tourism, and heritage tourism, among others. Most models of alternative tourism development emphasize themes that aim to counteract the perceived negative impacts of conventional or mass tourism. As such, the objectives of these models of tourism development tend to focus on minimizing environmental impacts, supporting biodiversity conservation, empowering local communities, alleviating poverty, and engendering pleasant relationships between tourists and residents.

Approaches to alternative tourism development tend to overlap with themes of responsible tourism, and the two terms are frequently used interchangeably. Responsible tourism has been characterized in terms of numerous elements, including

ensuring that communities are involved in and benefit from tourism;

respecting local, natural, and cultural environments;

involving the local community in planning and decision-making;

using local resources sustainably;

behaving in ways that are sensitive to the host culture;

maintaining and encouraging natural, economic, and cultural diversity; and

assessing environmental, social, and economic impacts as a prerequisite to tourism development (Spenceley, 2012 ).

Hetzer ( 1965 ) identified four fundamental principles or perquisites for a more responsible form of tourism: (a) minimum environmental impact; (b) minimum impact on and maximum respect for host cultures; (c) maximum economic benefits to the host country; and (d) maximum leisure satisfaction to participating tourists.

The history of ecotourism is closely connected with the emergence of sustainable development, as it was born out of a concern for the conservation of biodiversity. Ecotourism is a form of tourism that aims to minimize local environmental impacts while bringing benefits to protected areas and the people living around those lands (Honey, 2008 ). Ecotourism represents a small segment of nature-based tourism, which is understood as tourism based on the natural attractions of an area, such as scenic areas and wildlife (Gössling, 1999 ). The ecotourism movement gained momentum in the 1990s, primarily in developing countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, and nearly all countries are now engaged in some form of ecotourism. In some communities, ecotourism is the primary economic activity and source of income and economic development.

The term “ecotourism” was coined by Hector Ceballos-Lascuráin and defined by him as “tourism that consists in travelling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated natural areas with the specific object of studying, admiring, and enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals” (Ceballos-Lascuráin, 1987 , p. 13). In discussing ecotourism resources, he also made reference to “any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas” (Ceballos-Lascuráin, 1987 , p. 14). The basic precepts of ecotourism had been discussed long before the actual use of the term. Twenty years earlier, Hetzer ( 1965 ) referred to a form of tourism “based principally upon natural and archaeological resources such as caves, fossil sites (and) archaeological sites.” Thus, both natural resources and cultural resources were integrated into ecotourism frameworks from the earliest manifestations.

Costa Rica is well known for having successfully integrated ecotourism in its overall strategy for sustainable development, and numerous case studies of ecotourism in Costa Rica appear in the literature (Chase et al., 1998 ; Fennell & Eagles, 1990 ; Gray & Campbell, 2007 ; Hearne & Salinas, 2002 ). Ecotourism in Costa Rica has been seen as having supported the economic development of the country while promoting biodiversity conservation in its extensive network of protected areas. Chase et al. ( 1998 ) estimated the demand for ecotourism in a study of differential pricing of entrance fees at national parks in Costa Rica. The authors estimated elasticities associated with the own-price, cross-price, and income variables and found that the elasticities of demand were significantly different between three different national park sites. The results reveal the heterogeneity characterizing tourist behavior and park attractions and amenities. Hearne and Salinas ( 2002 ) used choice experiments to examine the preferences of domestic and foreign tourists in Costa Rica in an ecotourism site. Both sets of tourists demonstrated a preference for improved infrastructure, more information, and lower entrance fees. Foreign tourists demonstrated relatively stronger preferences for the inclusion of restrictions in the access to some trails.

Ecotourism has also been studied extensively in Kenya (Southgate, 2006 ), Malaysia (Lian Chan & Baum, 2007 ), Nepal (Baral et al., 2008 ), Peru (Stronza, 2007 ), and Taiwan (Lai & Nepal, 2006 ), among many other countries. Numerous case studies have demonstrated the potential for ecotourism to contribute to sustainable development by providing support for biodiversity conservation, local livelihoods, and regional development.

Community-Based Tourism

Community-based tourism (CBT) is a model of tourism development that emphasizes the development of local communities and allows for local residents to have substantial control over its development and management, and a major proportion of the benefits remain within the community. CBT emerged during the 1970s as a response to the negative impacts of the international mass tourism development model (Cater, 1993 ; Hall & Lew, 2009 ; Turner & Ash, 1975 ; Zapata et al., 2011 ).

Community-based tourism has been examined for its potential to contribute to poverty reduction. In a study of the viability of the CBT model to support socioeconomic development and poverty alleviation in Nicaragua, tourism was perceived by participants in the study to have an impact on employment creation in their communities (Zapata et al., 2011 ). Tourism was seen to have had positive impacts on strengthening local knowledge and skills, particularly on the integration of women to new roles in the labor market. One of the main perceived gains regarding the environment was the process of raising awareness regarding the conservation of natural resources. The small scale of CBT operations and low capacity to accommodate visitors was seen as a limitation of the model.

Spenceley ( 2012 ) compiled case studies of community-based tourism in countries in southern Africa, including Botswana, Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In this volume, authors characterize community-based and nature-based tourism development projects in the region and demonstrate how community participation in planning and decision-making has generated benefits for local residents and supported conservation initiatives. They contend that responsible tourism practices are of particular importance in the region because of the rich biological diversity, abundant charismatic wildlife, and the critical need for local economic development and livelihood strategies.

In Kenya, CBT enterprises were not perceived to have made a significant impact on poverty reduction at an individual household level, in part because the model relied heavily on donor funding, reinforcing dependency and poverty (Manyara & Jones, 2007 ). The study identified several critical success factors for CBT enterprises, namely, awareness and sensitization, community empowerment, effective leadership, and community capacity building, which can inform appropriate tourism policy formulation in Kenya. The impacts of CBT on economic development and poverty reduction would be greatly enhanced if tourism initiatives were able to emphasize independence, address local community priorities, enhance community empowerment and transparency, discourage elitism, promote effective community leadership, and develop community capacity to operate their own enterprises more efficiently.

Pro-Poor Tourism

Pro-poor tourism is a model of tourism development that brings net benefits to people living in poverty (Ashley et al., 2001 ; Harrison, 2008 ). Although its theoretical foundations and development objectives overlap to some degree with those of community-based tourism and other models of AT, the key distinctive feature of pro-poor tourism is that it places poor people and poverty at the top of the agenda. By focusing on a very simple and incontrovertibly moral idea, namely, the net benefits of tourism to impoverished people, the concept has broad appeal to donors and international aid agencies. Harnessing the economic benefits of tourism for pro-poor growth means capitalizing on the advantages while reducing negative impacts to people living in poverty (Ashley et al., 2001 ). Pro-poor approaches to tourism development include increasing access of impoverished people to economic benefits; addressing negative social and environmental impacts associated with tourism; and focusing on policies, processes, and partnerships that seek to remove barriers to participation by people living in poverty. At the local level, pro-poor tourism can play a very significant role in livelihood security and poverty reduction (Ashley & Roe, 2002 ).

Rogerson ( 2011 ) argues that the growth of pro-poor tourism initiatives in South Africa suggests that the country has become a laboratory for the testing and evolution of new approaches toward sustainable development planning that potentially will have relevance for other countries in the developing world. A study of pro-poor tourism development initiatives in Laos identified a number of favorable conditions for pro-poor tourism development, including the fact that local people are open to tourism and motivated to participate (Suntikul et al., 2009 ). The authors also noted a lack of development in the linkages that could optimize the fulfilment of the pro-poor agenda, such as training or facilitation of local people’s participation in pro-poor tourism development at the grassroots level.

Critics of the model have argued that pro-poor tourism is based on an acceptance of the status quo of existing capitalism, that it is morally indiscriminate and theoretically imprecise, and that its practitioners are academically and commercially marginal (Harrison, 2008 ). As Chok et al. ( 2007 ) indicate, the focus “on poor people in the South reflects a strong anthropocentric view . . . and . . . environmental benefits are secondary to poor peoples’” benefits (p. 153).

Harrison ( 2008 ) argues that pro-poor tourism is not a distinctive approach to tourism as a development tool and that it may be easier to discuss what pro-poor tourism is not than what it is. He concludes that it is neither anticapitalist nor inconsistent with mainstream tourism on which it relies; it is neither a theory nor a model and is not a niche form of tourism. Further, he argues that it has no distinctive method and is not only about people living in poverty.

Slow Tourism

The concept of slow tourism has emerged as a model of sustainable tourism development, and as such, it lacks an exact definition. The concept of slow tourism traces its origin back to some institutionalized social movements such as “slow food” and “slow cities” that began in Italy in the 1990s and spread rapidly around the world (Fullagar et al., 2012 ; Oh et al., 2016 , p. 205). Advocates of slow tourism tend to emphasize slowness in terms of speed, mobility, and modes of transportation that generate less environmental pollution. They propose niche marketing for alternative forms of tourism that focus on quality upgrading rather than merely increasing the quantity of visitors via the established mass-tourism infrastructure (Conway & Timms, 2010 ).

In the context of the Caribbean region, slow tourism has been promoted as more culturally sensitive and authentic, as compared to the dominant mass tourism development model that is based on all-inclusive beach resorts dependent on foreign investment (Conway & Timms, 2010 ). Recognizing its value as an alternative marketing strategy, Conway and Timms ( 2010 ) make the case for rebranding alternative tourism in the Caribbean as a means of revitalizing the sector for the changing demands of tourists in the 21st century . They suggest that slow tourism is the antithesis of mass tourism, which “relies on increasing the quantity of tourists who move through the system with little regard to either the quality of the tourists’ experience or the benefits that accrue to the localities the tourist visits” (Conway & Timms, 2010 , p. 332). The authors draw on cases from Barbados, the Grenadines, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago to characterize models of slow tourism development in remote fishing villages and communities near nature preserves and sea turtle nesting sites.

Although there is a growing interest in the concept of slow tourism in the literature, there seems to be little agreement about the exact nature of slow tourism and whether it is a niche form of special interest tourism or whether it represents a more fundamental potential shift across the industry. Conway and Timms ( 2010 ) focus on the destination, advocating for slow tourism in terms of a promotional identity for an industry in need of rebranding. Caffyn ( 2012 , p. 77) discusses the implementation of slow tourism in terms of “encouraging visitors to make slower choices when planning and enjoying their holidays.” It is not clear whether slow tourism is a marketing strategy, a mindset, or a social movement, but the literature on slow tourism nearly always equates the term with sustainable tourism (Caffyn, 2012 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Oh et al., 2016 ). Caffyn ( 2012 , p. 80) suggests that slow tourism could offer a “win–win,” which she describes as “a more sustainable form of tourism; keeping more of the economic benefits within the local community and destination; and delivering a more meaningful and satisfying experience.” Research on slow tourism is nascent, and thus the contribution of slow tourism to sustainable development is not well understood.

Impacts of Tourism Development

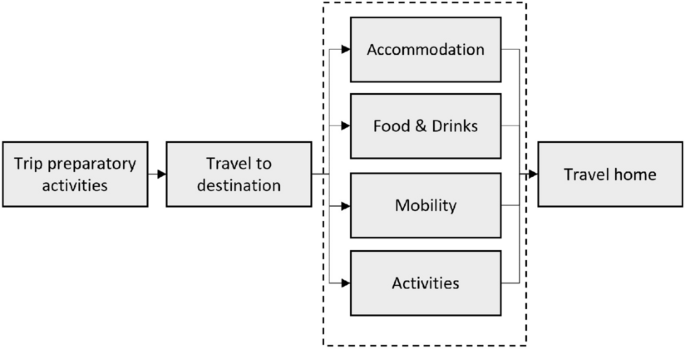

The role of tourism in sustainable development can be examined through an understanding of the economic, environmental, and social impacts of tourism. Tourism is a global phenomenon that involves travel, recreation, the consumption of food, overnight accommodations, entertainment, sightseeing, and other activities that simultaneously intersect the lives of local residents, businesses, and communities. The impacts of tourism involve benefits and costs to all groups, and some of these impacts cannot easily be measured. Nevertheless, they have been studied extensively in the literature, which provides some context for how these benefits and costs are distributed.

Economic Impacts of Tourism

The travel and tourism sector is one of the largest components of the global economy, and global tourism has increased exponentially since the end of the Second World War (UNWTO, 2020 ). The direct, indirect, and induced economic impact of global travel accounted for 8.9 trillion U.S. dollars in contribution to the global gross domestic product (GDP), or 10.3% of global GDP. The global travel and tourism sector supports approximately 330 million jobs, or 1 in 10 jobs around the world. From an economic perspective, tourism plays a significant role in sustainable development. In many developing countries, tourism has the potential to play a unique role in income generation and distribution relative to many other industries, in part because of its high multiplier effect and consumption of local goods and services. However, research on the economic impacts of tourism has shown that this potential has rarely been fully realized (Liu, 2003 ).

Numerous studies have examined the impact of tourism expenditure on GDP, income, employment, and public sector revenue. Narayan ( 2004 ) used a computable general equilibrium model to estimate the economic impact of tourism growth on the economy of Fiji. Tourism is Fiji’s largest industry, with average annual growth of 10–12%; and as a middle-income country, tourism is critical to Fiji’s economic development. The findings indicate that an increase in tourism expenditures was associated with an increase in GDP, an improvement in the country’s balance of payments, and an increase in real consumption and national welfare. Evidence suggests that the benefits of tourism expansion outweigh any export effects caused by an appreciation of the exchange rate and an increase in domestic prices and wages.

Seetanah ( 2011 ) examined the potential contribution of tourism to economic growth and development using panel data of 19 island economies around the world from 1990 to 2007 and revealed that tourism development is an important factor in explaining economic performance in the selected island economies. The results have policy implications for improving economic growth by harnessing the contribution of the tourism sector. Pratt ( 2015 ) modeled the economic impact of tourism for seven small island developing states in the Pacific, the Caribbean, and the Indian Ocean. In most states, the transportation sector was found to have above-average linkages to other sectors of the economy. The results revealed some advantages of economies of scale for maximizing the economic contribution of tourism.

Apergis and Payne ( 2012 ) examined the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth for a panel of nine Caribbean countries. The panel of Caribbean countries includes Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. The authors use a panel error correction model to reveal bidirectional causality between tourism and economic growth in both the short run and the long run. The presence of bidirectional causality reiterates the importance of the tourism sector in the generation of foreign exchange income and in financing the production of goods and services within these countries. Likewise, stable political institutions and adequate government policies to ensure the appropriate investment in physical and human capital will enhance economic growth. In turn, stable economic growth will provide the resources needed to develop the tourism infrastructure for the success of the countries’ tourism sector. Thus, policy makers should be cognizant of the interdependent relationship between tourism and economic growth in the design and implementation of economic policy. The mixed nature of these results suggest that the relationship between tourism and economic growth depends largely on the social and economic context as well as the role of tourism in the economy.

The economic benefits and costs of tourism are frequently distributed unevenly. An analysis of the impact of wildlife conservation policies in Zambia on household welfare found that households located near national parks earn higher levels of income from wage employment and self-employment than other rural households in the country, but they were also more likely to suffer crop losses related to wildlife conflicts (Richardson et al., 2012 ). The findings suggest that tourism development and wildlife conservation can contribute to pro-poor development, but they may be sustainable only if human–wildlife conflicts are minimized or compensated.

Environmental Impacts of Tourism

The environmental impacts of tourism are significant, ranging from local effects to contributions to global environmental change (Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ). Tourism is both dependent on water resources and a factor in global and local freshwater use. Tourists consume water for drinking, when showering and using the toilet, when participating in activities such as winter ski tourism (i.e., snowmaking), and when using swimming pools and spas. Fresh water is also needed to maintain hotel gardens and golf courses, and water use is embedded in tourism infrastructure development (e.g., accommodations, laundry, dining) and in food and fuel production. Direct water consumption in tourism is estimated to be approximately 350 liters (L) per guest night for accommodation; when indirect water use from food, energy, and transport are considered, total water use in tourism is estimated to be approximately 6,575 L per guest night, or 27,800 L per person per trip (Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ). In addition, tourism contributes to the pollution of oceans as well as lakes, rivers, and other freshwater systems (Gössling, 2002 ; Gössling et al., 2011 ).

The clearing and conversion of land is central for tourism development, and in many cases, the land used for tourism includes roads, airports, railways, accommodations, trails, pedestrian walks, shopping areas, parking areas, campgrounds, vacation homes, golf courses, marinas, ski resorts, and indirect land use for food production, disposal of solid wastes, and the treatment of wastewater (Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ). Global land use for accommodation is estimated to be approximately 42 m 2 per bed. Total global land use for tourism is estimated to be nearly 62,000 km 2 , or 11.7 m 2 per tourist; more than half of this estimate is represented by land use for traffic infrastructure.

Tourism and hospitality have direct and indirect links to nearly all aspects of food production, preparation, and consumption because of the quantities of food consumed in tourism contexts (Gössling et al., 2011 ). Food production has significant implications for sustainable development, given the growing global demand for food. The implications include land conversion, losses to biodiversity, changes in nutrient cycling, and contributions to greenhouse emissions that are associated with global climate change (Vitousek et al., 1997 ). Global food use for tourism is estimated to be approximately 39.4 megatons 1 (Mt), about 38% than the amount of food consumed at home. This equates to approximately 1,800 grams (g) of food consumed per tourist per day.

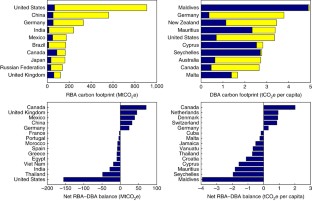

Although tourism has been promoted as a low-impact, nonextractive option for economic development, (Gössling, 2000 ), assessments reveal that such pursuits have a significant carbon footprint, as tourism is significantly more carbon intensive than other potential areas of economic development (Lenzen et al., 2018 ). Tourism is dependent on energy, and virtually all energy use in the tourism sector is derived from fossil fuels, which contribute to global greenhouse emissions that are associated with global climate change. Energy use for tourism has been estimated to be approximately 3,575 megajoules 2 (MJ) per trip, including energy for travel and accommodations (Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ). A previous estimate of global carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) emissions from tourism provided values of 1.12 gigatons 3 (Gt) of CO 2 , amounting to about 3% of global CO 2 -equivalent (CO 2 e) emissions (Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ). However, these analyses do not cover the supply chains underpinning tourism and do not therefore represent true carbon footprints. A more complete analysis of the emissions from energy consumption necessary to sustain the tourism sector would include food and beverages, infrastructure construction and maintenance, retail, and financial services. Between 2009 and 2013 , tourism’s global carbon footprint is estimated to have increased from 3.9 to 4.5 GtCO 2 e, four times more than previously estimated, accounting for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Lenzen et al., 2018 ). The majority of this footprint is exerted by and within high-income countries. The rising global demand for tourism is outstripping efforts at decarbonization of tourism operations and as a result is accelerating global carbon emissions.

Social Impacts of Tourism

The social impacts of tourism have been widely studied, with an emphasis on residents’ perceptions in the host community (Sharpley, 2014 ). Case studies include research conducted in Australia (Faulkner & Tideswell, 1997 ; Gursoy et al., 2010 ; Tovar & Lockwood, 2008 ), Belize (Diedrich & Garcia-Buades, 2008 ), China (Gu & Ryan, 2008 ), Fiji (King et al., 1993 ), Greece (Haralambopoulos & Pizam, 1996 ; Tsartas, 1992 ), Hungary (Rátz, 2000 ), Thailand (Huttasin, 2008 ), Turkey (Kuvan & Akan, 2005 ), the United Kingdom (Brunt & Courtney, 1999 ; Haley et al., 2005 ), and the United States (Andereck et al., 2005 ; Milman & Pizam, 1988 ), among others. The social impacts of tourism are difficult to measure, and most published studies are mainly concerned with the social impacts on the host communities rather than the impacts on the tourists themselves.

Studies of residents’ perceptions of tourism are typically conducted using household surveys. In most cases, residents recognize the economic dependence on tourism for income, and there is substantial evidence to suggest that working in or owning a business in tourism or a related industry is associated with more positive perceptions of tourism (Andereck et al., 2007 ). The perceived nature of negative effects is complex and often conveys a dislike of crowding, traffic congestion, and higher prices for basic needs (Deery et al., 2012 ). When the number of tourists far exceeds that of the resident population, negative attitudes toward tourism may manifest (Diedrich & Garcia-Buades, 2008 ). However, residents who recognize negative impacts may not necessarily oppose tourism development (King et al., 1993 ).

In some regions, little is known about the social and cultural impacts of tourism despite its dominance as an economic sector. Tourism is a rapidly growing sector in Cuba, and it is projected to grow at rates that exceed the average projected growth rates for the Caribbean and the world overall (Salinas et al., 2018 ). Still, even though there has been rapid tourism development in Cuba, there has been little research related to the environmental and sociocultural impacts of this tourism growth (Rutty & Richardson, 2019 ).

In some international tourism contexts, studies have found that residents are generally resentful toward tourism because it fuels inequality and exacerbates racist attitudes and discrimination (Cabezas, 2004 ; Jamal & Camargo, 2014 ; Mbaiwa, 2005 ). Other studies revealed similar narratives and recorded statements of exclusion and socioeconomic stratification (Sanchez & Adams, 2008 ). Local residents often must navigate the gaps in the racialized, gendered, and sexualized structures imposed by the global tourism industry and host-country governments (Cabezas, 2004 ).

However, during times of economic crisis, residents may develop a more permissive view as their perceptions of the costs of tourism development decrease (Garau-Vadell et al., 2018 ). This increased positive attitude is not based on an increase in the perception of positive impacts of tourism, but rather on a decrease in the perception of the negative impacts.

There is a growing body of research on Indigenous and Aboriginal tourism that emphasizes justice issues such as human rights and self-empowerment, control, and participation of traditional owners in comanagement of destinations (Jamal & Camargo, 2014 ; Ryan & Huyton, 2000 ; Whyte, 2010 ).

Sustainability of Tourism

A process or system is said to be sustainable to the extent that it is robust, resilient, and adaptive (Anderies et al., 2013 ). By most measures, the global tourism system does not meet these criteria for sustainability. Tourism is not robust in that it cannot resist threats and perturbations, such as economic shocks, public health pandemics, war, and other disruptions. Tourism is not resilient in that it does not easily recover from failures, such as natural disasters or civil unrest. Furthermore, tourism is not adaptive in that it is often unable to change in response to external conditions. One example that underscores the failure to meet all three criteria is the dependence of tourism on fossil fuels for transportation and energy, which are key inputs for tourism development. This dependence itself is not sustainable (Wheeller, 2007 ), and thus the sustainability of tourism is questionable.

Liu ( 2003 ) notes that research related to the role of tourism in sustainable development has emphasized supply-side concepts such as sustaining tourism resources and ignored the demand side, which is particularly vulnerable to social and economic shocks. Tourism is vulnerable to both localized and global shocks. Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to localized shocks include disaster vulnerability in coastal Thailand (Calgaro & Lloyd, 2008 ), bushfires in northeast Victoria in Australia (Cioccio & Michael, 2007 ), forest fires in British Columbia, Canada (Hystad & Keller, 2008 ); and outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the United Kingdom (Miller & Ritchie, 2003 ).

Like most other economic sectors, tourism is vulnerable to the impacts of earthquakes, particularly in areas where tourism infrastructure may not be resilient to such shocks. Numerous studies have examined the impacts of earthquake events on tourism, including studies of the aftermath of the 1997 earthquake in central Italy (Mazzocchi & Montini, 2001 ), the 1999 earthquake in Taiwan (Huan et al., 2004 ; Huang & Min, 2002 ), and the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in western Sichuan, China (Yang et al., 2011 ), among others.

Tourism is vulnerable to extreme weather events. Regional economic strength has been found to be associated with lower vulnerability to natural disasters. Kim and Marcoullier ( 2015 ) examined the vulnerability and resilience of 10 tourism-based regional economies that included U.S. national parks or protected seashores situated on the Gulf of Mexico or Atlantic Ocean coastline that were affected by several hurricanes over a 26-year period. Regions with stronger economic characteristics prior to natural disasters were found to have lower disaster losses than regions with weaker economies.

Tourism is extremely sensitive to oil spills, whatever their origin, and the volume of oil released need not be large to generate significant economic losses (Cirer-Costa, 2015 ). Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to the localized shock of an oil spill include research on the impacts of oil spills in Alaska (Coddington, 2015 ), Brazil (Ribeiro et al., 2020 ), Spain (Castanedo et al., 2009 ), affected regions in the United States along the Gulf of Mexico (Pennington-Gray et al., 2011 ; Ritchie et al., 2013 ), and the Republic of Korea (Cheong, 2012 ), among others. Future research on the vulnerability of tourist destinations to oil spills should also incorporate freshwater environments, such as lakes, rivers, and streams, where the rupture of oil pipelines is more frequent.

Significant attention has been paid to assessing the vulnerability of tourist destinations to acts of terrorism and the impacts of terrorist attacks on regional tourist economies (Liu & Pratt, 2017 ). Such studies include analyses of the impacts of terrorist attacks on three European countries, Greece, Italy, and Austria (Enders et al., 1992 ); the impact of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States (Goodrich, 2002 ); terrorism and tourism in Nepal (Bhattarai et al., 2005 ); vulnerability of tourism livelihoods in Bali (Baker & Coulter, 2007 ); the impact of terrorism on tourist preferences for destinations in the Mediterranean and the Canary Islands (Arana & León, 2008 ); the 2011 massacres in Olso and Utøya, Norway (Wolff & Larsen, 2014 ); terrorism and political violence in Tunisia (Lanouar & Goaied, 2019 ); and the impact of terrorism on European tourism (Corbet et al., 2019 ), among others. Pizam and Fleischer ( 2002 ) studied the impact of acts of terrorism on tourism demand in Israel between May 1991 and May 2001 , and they confirmed that the frequency of acts of terrorism had caused a larger decline in international tourist arrivals than the severity of these acts. Most of these are ex post studies, and future assessments of the underlying conditions of destinations could reveal a deeper understanding of the vulnerability of tourism to terrorism.

Tourism is vulnerable to economic crisis, both local economic shocks (Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005 ; Stylidis & Terzidou, 2014 ) and global economic crisis (Papatheodorou et al., 2010 ; Smeral, 2010 ). Okumus and Karamustafa ( 2005 ) evaluated the impact of the February 2001 economic crisis in Turkey on tourism, and they found that the tourism industry was poorly prepared for the economic crisis despite having suffered previous impacts related to the Gulf War in the early 1990s, terrorism in Turkey in the 1990s, the civil war in former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, an internal economic crisis in 1994 , and two earthquakes in the northwest region of Turkey in 1999 . In a study of the attitudes and perceptions of citizens of Greece, Stylidis and Terzidou ( 2014 ) found that economic crisis is associated with increased support for tourism development, particularly out of self-interest. Economic crisis diminishes residents’ concern for environmental issues. In a study of the behavior of European tourists amid an economic crisis, Eugenio-Martin and Campos-Soria ( 2014 ) found that the probability of households cutting back on travel expenditures depends largely on the climate and economic conditions of tourists’ home countries, and households that do reduce travel spending engage in tourism closer to home.

Becken and Lennox ( 2012 ) studied the implications of a long-term increase in oil prices for tourism in New Zealand, and they estimate that a doubling of oil prices is associated with a 1.7% decrease in real gross national disposable income and a 9% reduction in the real value of tourism exports. Chatziantoniou et al. ( 2013 ) investigated the relationship among oil price shocks, tourism variables, and economic indicators in four European Mediterranean countries and found that aggregate demand oil price shocks generated a lagged effect on tourism-generated income and economic growth. Kisswani et al. ( 2020 ) examined the asymmetric effect of oil prices on tourism receipts and the sensitive susceptibility of tourism to oil price changes using nonlinear analysis. The findings document a long-run asymmetrical effect for most countries, after incorporating the structural breaks, suggesting that governments and tourism businesses and organizations should interpret oil price fluctuations cautiously.

Finally, the sustainability of tourism has been shown to be vulnerable to the outbreak of infectious diseases, including the impact of the Ebola virus on tourism in sub-Saharan Africa (Maphanga & Henama, 2019 ; Novelli et al., 2018 ) and in the United States (Cahyanto et al., 2016 ). The literature also includes studies of the impact of swine flu on tourism demand in Brunei (Haque & Haque, 2018 ), Mexico (Monterrubio, 2010 ), and the United Kingdom (Page et al., 2012 ), among others. In addition, rapid assessments of the impacts of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 have documented severe disruptions and cessations of tourism because of unprecedented global travel restrictions and widespread restrictions on public gatherings (Gössling et al., 2020 ; Qiu et al., 2020 ; Sharma & Nicolau, 2020 ). Hotels, airlines, cruise lines, and car rentals have all experienced a significant decrease globally because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the shock to the industry is significant enough to warrant concerns about the long-term outlook (Sharma & Nicolau, 2020 ). Qiu et al. ( 2020 ) estimated the social costs of the pandemic to tourism in three cities in China (Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Wuhan), and they found that most respondents were willing to pay for risk reduction and action in responding to the pandemic crisis; there was no significant difference between residents’ willingness to pay in the three cities. Some research has emphasized how lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic can prepare global tourism for an economic transformation that is needed to mitigate the impacts of climate change (Brouder, 2020 ; Prideaux et al., 2020 ).

It is clear that tourism has contributed significantly to economic development globally, but its role in sustainable development is uncertain, contested, and potentially paradoxical. This is due, in part, to the contested nature of sustainable development itself. Tourism has been promoted as a low-impact, nonextractive option for economic development, particularly for developing countries (Gössling, 2000 ), and many countries have managed to increase their participation in the global economy through development of international tourism. Tourism development has been viewed as an important sector for investment to enhance economic growth, poverty alleviation, and food security, and the sector provides an alternative opportunity to large-scale development projects and extractive industries that contribute to emissions of pollutants and threaten biodiversity and cultural values. However, global evidence from research on the economic impacts of tourism has shown that this potential has rarely been realized (Liu, 2003 ).

The role of tourism in sustainable development has been studied extensively and with a variety of perspectives, including the conceptualization of alternative or responsible forms of tourism and the examination of economic, environmental, and social impacts of tourism development. The research has generally concluded that tourism development has contributed to sustainable development in some cases where it is demonstrated to have provided support for biodiversity conservation initiatives and livelihood development strategies. As an economic sector, tourism is considered to be labor intensive, providing opportunities for poor households to enhance their livelihood through the sale of goods and services to foreign tourists.

Nature-based tourism approaches such as ecotourism and community-based tourism have been successful at attracting tourists to parks and protected areas, and their spending provides financial support for biodiversity conservation, livelihoods, and economic growth in developing countries. Nevertheless, studies of the impacts of tourism development have documented negative environmental impacts locally in terms of land use, food and water consumption, and congestion, and globally in terms of the contribution of tourism to climate change through the emission of greenhouse gases related to transportation and other tourist activities. Studies of the social impacts of tourism have documented experiences of discrimination based on ethnicity, gender, race, sex, and national identity.

The sustainability of tourism as an economic sector has been examined in terms of its vulnerability to civil conflict, economic shocks, natural disasters, and public health pandemics. Most studies conclude that tourism may have positive impacts for regional development and environmental conservation, but there is evidence that tourism inherently generates negative environmental impacts, primarily through pollutions stemming from transportation. The regional benefits of tourism development must be considered alongside the global impacts of increased transportation and tourism participation. Global tourism has also been shown to be vulnerable to economic crises, oil price shocks, and global outbreaks of infectious diseases. Given that tourism is dependent on energy, the movement of people, and the consumption of resources, virtually all tourism activities have significant economic, environmental, and sustainable impacts. As such, the role of tourism in sustainable development is highly questionable. Future research on the role of tourism in sustainable development should focus on reducing the negative impacts of tourism development, both regionally and globally.

Further Reading

- Bramwell, B. , & Lane, B. (1993). Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 1 (1), 1–5.

- Buckley, R. (2012). Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Annals of Tourism Research , 39 (2), 528–546.

- Butler, R. W. (1991). Tourism, environment, and sustainable development. Environmental Conservation , 18 (3), 201–209.

- Butler, R. W. (1999). Sustainable tourism: A state‐of‐the‐art review. Tourism Geographies , 1 (1), 7–25.

- Clarke, J. (1997). A framework of approaches to sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 5 (3), 224–233.

- Fennell, D. A. (2020). Ecotourism (5th ed.). Routledge.

- Gössling, S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Global Environmental Change , 12 (4), 283–302.

- Honey, M. (2008). Ecotourism and sustainable development: Who owns paradise? (2nd ed.). Island Press.

- Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach . Routledge.

- Jamal, T. , & Camargo, B. A. (2014). Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 22 (1), 11–30.

- Liburd, J. J. , & Edwards, D. (Eds.). (2010). Understanding the sustainable development of tourism . Oxford.

- Liu, Z. (2003). Sustainable tourism development: A critique. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 11 (6), 459–475.

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 28 (11), 1932–1946.

- Adams, W. M. (2009). Green development: Environment and sustainability in a developing world (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Andereck, K. L. , Valentine, K. M. , Knopf, R. A. , & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research , 32 (4), 1056–1076.

- Andereck, K. , Valentine, K. , Vogt, C. , & Knopf, R. (2007). A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 15 (5), 483–502.

- Anderies, J. M. , Folke, C. , Walker, B. , & Ostrom, E. (2013). Aligning key concepts for global change policy: Robustness, resilience, and sustainability . Ecology and Society , 18 (2), 8.

- Apergis, N. , & Payne, J. E. (2012). Tourism and growth in the Caribbean–evidence from a panel error correction model. Tourism Economics , 18 (2), 449–456.

- Arana, J. E. , & León, C. J. (2008). The impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research , 35 (2), 299–315.

- Ashley, C. , & Roe, D. (2002). Making tourism work for the poor: Strategies and challenges in southern Africa. Development Southern Africa , 19 (1), 61–82.

- Ashley, C. , Roe, D. , & Goodwin, H. (2001). Pro-poor tourism strategies: Making tourism work for the poor: A review of experience (No. 1). Overseas Development Institute.

- Baker, K. , & Coulter, A. (2007). Terrorism and tourism: The vulnerability of beach vendors’ livelihoods in Bali. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 15 (3), 249–266.

- Baral, N. , Stern, M. J. , & Bhattarai, R. (2008). Contingent valuation of ecotourism in Annapurna conservation area, Nepal: Implications for sustainable park finance and local development. Ecological Economics , 66 (2–3), 218–227.

- Becken, S. , & Lennox, J. (2012). Implications of a long-term increase in oil prices for tourism. Tourism Management , 33 (1), 133–142.

- Beckerman, W. (1994). “Sustainable development”: Is it a useful concept? Environmental Values , 3 (3), 191–209.

- Bhattarai, K. , Conway, D. , & Shrestha, N. (2005). Tourism, terrorism and turmoil in Nepal. Annals of Tourism Research , 32 (3), 669–688.

- Blewitt, J. (2015). Understanding sustainable development (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies , 22 (3), 484–490.

- Brunt, P. , & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research , 26 (3), 493–515.

- Buckley, R. (2011). Tourism and environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources , 36 , 397–416.

- Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien , 24 (1), 5–12.

- Butler, R. , & Hinch, T. (Eds.). (2007). Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications . Routledge.

- Cabezas, A. L. (2004). Between love and money: Sex, tourism, and citizenship in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society , 29 (4), 987–1015.

- Caffyn, A. (2012). Advocating and implementing slow tourism. Tourism Recreation Research , 37 (1), 77–80.

- Cahyanto, I. , Wiblishauser, M. , Pennington-Gray, L. , & Schroeder, A. (2016). The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tourism Management Perspectives , 20 , 195–203.

- Calgaro, E. , & Lloyd, K. (2008). Sun, sea, sand and tsunami: Examining disaster vulnerability in the tourism community of Khao Lak, Thailand. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography , 29 (3), 288–306.

- Castanedo, S. , Juanes, J. A. , Medina, R. , Puente, A. , Fernandez, F. , Olabarrieta, M. , & Pombo, C. (2009). Oil spill vulnerability assessment integrating physical, biological and socio-economical aspects: Application to the Cantabrian coast (Bay of Biscay, Spain). Journal of Environmental Management , 91 (1), 149–159.

- Cater, E. (1993). Ecotourism in the Third World: Problems for sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management , 14 (2), 85–90.

- Ceballos-Lascuráin, H. (1987, January). The future of “ecotourism.” Mexico Journal , 17 , 13–14.

- Chase, L. C. , Lee, D. R. , Schulze, W. D. , & Anderson, D. J. (1998). Ecotourism demand and differential pricing of national park access in Costa Rica. Land Economics , 74 (4), 466–482.

- Chatziantoniou, I. , Filis, G. , Eeckels, B. , & Apostolakis, A. (2013). Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: A structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Management , 36 (C), 331–341.

- Cheong, S. M. (2012). Fishing and tourism impacts in the aftermath of the Hebei-Spirit oil spill. Journal of Coastal Research , 28 (6), 1648–1653.

- Chok, S. , Macbeth, J. , & Warren, C. (2007). Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: A critical analysis of “pro-poor tourism” and implications for sustainability. Current Issues in Tourism , 10 (2–3), 144–165.

- Cioccio, L. , & Michael, E. J. (2007). Hazard or disaster: Tourism management for the inevitable in Northeast Victoria. Tourism Management , 28 (1), 1–11.

- Cirer-Costa, J. C. (2015). Tourism and its hypersensitivity to oil spills. Marine Pollution Bulletin , 91 (1), 65–72.

- Coccossis, H. , & Nijkamp, P. (1995). Sustainable tourism development . Ashgate.

- Coddington, K. (2015). The “entrepreneurial spirit”: Exxon Valdez and nature tourism development in Seward, Alaska. Tourism Geographies , 17 (3), 482–497.

- Cohen, E. (1978). The impact of tourism on the physical environment. Annals of Tourism Research , 5 (2), 215–237.

- Conway, D. , & Timms, B. F. (2010). Re-branding alternative tourism in the Caribbean: The case for “slow tourism.” Tourism and Hospitality Research , 10 (4), 329–344.

- Corbet, S. , O’Connell, J. F. , Efthymiou, M. , Guiomard, C. , & Lucey, B. (2019). The impact of terrorism on European tourism. Annals of Tourism Research , 75 , 1–17.

- Daly, H. E. (1990). Toward some operational principles of sustainable development. Ecological Economics , 2 (1), 1–6.

- Deery, M. , Jago, L. , & Fredline, L. (2012). Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tourism Management , 33 (1), 64–73.

- Diedrich, A. , & Garcia-Buades, E. (2008). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management , 41 , 623–632.

- Durbarry, R. (2004). Tourism and economic growth: The case of Mauritius. Tourism Economics , 10 , 389–401.

- Elliott, S. M. , & Neirotti, L. D. (2008). Challenges of tourism in a dynamic island destination: The case of Cuba. Tourism Geographies , 10 (4), 375–402.

- Enders, W. , Sandler, T. , & Parise, G. F. (1992). An econometric analysis of the impact of terrorism on tourism. Kyklos , 45 (4), 531–554.

- Eugenio-Martin, J. L. , & Campos-Soria, J. A. (2014). Economic crisis and tourism expenditure cutback decision. Annals of Tourism Research , 44 , 53–73.

- Farrell, B. , & McLellan, R. (1987). Tourism and physical environment research. Annals of Tourism Research , 14 (1), 1–16.

- Faulkner, B. , & Tideswell, C. (1997). A framework for monitoring community impacts of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 5 (1), 3–28.

- Fennell, D. A. , & Eagles, P. F. (1990). Ecotourism in Costa Rica: A conceptual framework. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration , 8 (1), 23–34.

- Fullagar, S. , Markwell, K. , & Wilson, E. (Eds.). (2012). Slow tourism: Experiences and mobilities . Channel View.

- Garau-Vadell, J. B. , Gutierrez-Taño, D. , & Diaz-Armas, R. (2018). Economic crisis and residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism in mass tourism destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management , 7 , 68–75.

- Garrod, B. , & Fyall, A. (1998). Beyond the rhetoric of sustainable tourism? Tourism Management , 19 (3), 199–212.

- Ghimire, K. B. (Ed.). (2013). The native tourist: Mass tourism within developing countries . Routledge.

- Goodrich, J. N. (2002). September 11, 2001 attack on America: A record of the immediate impacts and reactions in the USA travel and tourism industry. Tourism Management , 23 (6), 573–580.