Deciphering the Journey

Posted in Features

Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

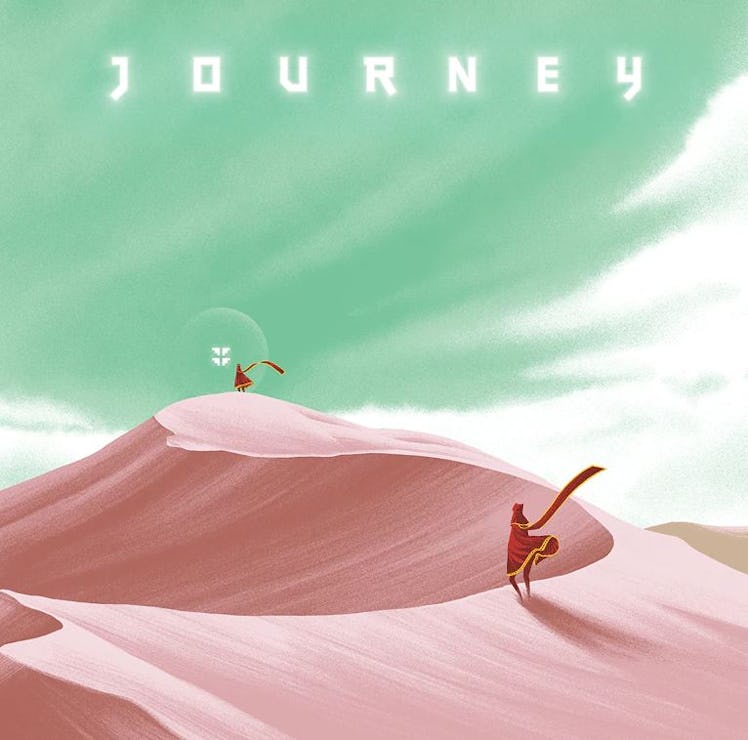

It doesn’t take much longer than an hour to reach the end of Journey, thatgamecompany’s recent indie jaunt across the desert. On the surface, it’s also a relatively lean game, stripped of all but the most basic interaction methods and never overtly thrusting a story in your face. In its seas of colour and its wordless narrative, it’s a fabulous exercise in minimalism. At least, that’s how it first appears.

In Journey, you walk, jump and play. You interact with the world by leaping or by singing at it, and you solve the game’s few puzzles via experimentation, learning the rules of this land as you exist within it. There are no dramatic characters intoning long, expository dialogue sequences, and you won’t find any diary entries bafflingly ripped out in chronological order. You uncover Journey’s mystery simply by experiencing it.

An hour isn’t long to unfurl the tale of an entire world, especially when much of that time is spent experimenting with its systems, sliding down sand dunes and singing to the co-op buddies who sometimes quietly drop into your game. And yet, Journey is infused with more character, more ideas and more meaning than any other recent release that springs to mind.

So: what does it all mean?

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/faf1/journey_16.jpg)

There are lots of theories, of course. It’s that way by design. Journey’s like a silent movie without any captions, and one in which the action on-screen is always faintly abstract, otherworldly and expressive. Or perhaps it’s like a ballet, an aural and kinetic display of ideas, but one where you’re not familiar with the source material. You come away with a thousand possible answers, but nothing to confirm your suspicions. You just know it was a hell of a show.

I’ve heard quite a few of these theories now. They range from the sensible to the surreal, from religious to scientific. I even had a discussion with a friend recently who was absolutely certain that Journey is a game about the nine months between conception and birth: he thought the ducking and diving fabric creatures represented sperm cells, the occasional enemies were threats of miscarriage, and the mountain – with that gaping opening at its peak – was the game’s enormous vagina.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think Journey is a game about sperm and vaginas, but I do think it’s a game about life. In fact, I think it’s a game about quite a lot of things. I spent a couple of days after finishing Journey thinking about what it could all mean. Each time I came up with a theory, or heard someone else’s, it seemed eminently plausible but still didn’t quite seem to fit. That lightbulb moment, the one where it all clicks into place, stubbornly refused to arrive.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/55b9/journey_13.jpg)

And then it did, and I settled on the theory I’ve stuck with. So here goes: Journey is a game about everything .

I do distinctly mean ‘everything’ rather than ‘anything’, too. While Journey was clearly intended to have its intricacies discussed and debated, I don’t view it as a story without a specific meaning. The reason none of those individual interpretations seemed quite right on their own is because they function as part of a much larger picture – a microcosm of an entire universe, its past, its present and its future.

The most obvious of Journey’s strands is the story of a civilisation, one that was built up from nothing but ultimately collapsed, leaving the starkly ruined landscape you see before you. This story is the one told in the abstractly animated cutscenes that bookend each chapter – the beautiful mural that scratches and paints itself as you watch, its symbols slowly growing into something more recognisable.

Why did this civilisation grow so huge, and why did it ultimately fail? These answers prove more elusive. We see what appears to be electricity flowing through a city’s veins, and it seems to be brought to its knees by explosive blasts. There are hints at scientific advancement, and of war, which would make perfect sense given the content explored in the rest of the game.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/56dd/journey_18.jpg)

There are very obvious religious overtones. At times the symbolism is enormous, with spiritual apparitions, Middle Eastern architecture and, in the game’s closing moments, a joyous take on the rapture that sees you rise from your body, through the snow-filled clouds and into the beautiful blue skies above. After lingering on your dying moments for an uncomfortable length of time, Journey shakes things up, and the game turns out not to end with your death, but with your incredible reincarnation.

But while Journey is a game about religion, it’s also a game about science. One of its other major themes is evolution: it’s about species adapting to their environment, growing and changing, gaining new abilities as they fight for survival. This is the case with your own character – you begin the game without the ability to jump, and the distance you may do so develops over time, allowing you to rise to Journey’s challenges. By the end, you find yourself in a place where the conditions are radically different – a blizzard-filled mountainous region, instead of a baking desert – and natural selection ostensibly writes you out of the story.

There are other visual cues to evolution, too. It might sound strange, but it’s the fabric that’s key. It begins as floating particles whose only ability is to increase the length of your own scarf. By the end they’ve become enormous floating dragons that transport you around the world, or coral-like formations that boost you skywards, allowing you access to areas you’d otherwise be unable to reach.

Journey is a game that operates on a macro and micro level simultaneously. So, while it’s a game about evolution, it’s also a game about simply growing up. You don’t understand Journey’s world when you first arrive in it. You learn by experimenting, by playing, and with the gentle guidance of others whom you don’t always fully understand.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/63f7/journey_6.jpg)

As you progress, you begin to understand them better. You meet more people. They all have slightly different ways of communicating – always through sound and movement, but in idiosyncratic styles – and you learn to recognise patterns. Meet someone late on in the game and you’ll likely find yourself communicating effortlessly, guiding new players around the world or being tempted towards hidden secrets by more experienced journeyers. You’ve learnt the communication systems of this world. It’s a game about language acquisition.

And it’s a game, perhaps most significantly, about the inevitability that life will follow its own path. Of course Journey’s society fell: it was inhabited by living, sentient beings, with all the flaws that come with such an existence. But along the way it birthed culture, and belief, and wonderful technology, the remnants of which you can see scattered around the retrospective showcase you experience as you jump, slide and glide your way through the game.

I might be wrong, naturally, but I hope I’m not – because I haven’t played many games that tackle such a range of huge topics with this majestic confidence. Come to think of it, I haven’t seen many films, or read many novels, for which I could say that either.

For something so starkly minimalist in its presentation, and a game without any dialogue, Journey is an extraordinary achievement: a game about life and death, and a tale that’s both personal and vast in its scope. It’s the story of existence, the enormous number of ways we interpret our lives, and the ways in which we react to those beliefs. Not bad for an hour-long game in which all you do is walk, jump and play.

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Filed under:

- Video Games

Ten Years Ago, ‘Journey’ Made a Convincing Case That Video Games Could Be Art

Creative director Jenova Chen conceived ‘Journey’ as an act of rebellion against commercial games. The decidedly emotional titles it inspired forgo violence and point scoring for matters closer to the heart.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70607909/journey.0.jpeg)

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Ten Years Ago, ‘Journey’ Made a Convincing Case That Video Games Could Be Art

To borrow internet parlance for a moment, Journey is a video game designed to hit you right in the feels. You play as an androgynous character dressed in a sweeping red robe, dwarfed by stark landscapes of sand and snow. Pushing the PlayStation controller’s left analog stick, you move forward, slowly at first, and then, later in the game, with exuberant speed, as if you’re surfing. Most of the time you’re alone, but if you’re lucky, you’ll come across another figure, its silhouette fluttering in the distance. You might travel together for a few minutes and then part ways, or perhaps you’ll reach the end of the game in one another’s company. Regardless, this time will feel almost miraculous—a chance encounter at the very edge of the world.

The game’s setting gleams with flecks of Gustav Klimt gold while a single towering mountain dominates the horizon. The game is called Journey for a reason, and its deliberately allegorical story curves toward tragedy, as if this is the fate awaiting us all. Unlike most games, you die only once. Rather than a cheap metaphor for failure, it’s something heavier—a crescendo, an act of self-annihilation.

Now, it’s widely accepted that games can move us in ways similar to novels, movies, or music, but in March 2012, when Journey came out on PS3, this simply wasn’t the case. Sure, there were the works of Fumito Ueda, Ico and Shadow of the Colossus —stark, artful games of the aughts from Japan that tugged more on the heartstrings than the itchy trigger finger. So too had the rise of independent games from 2008 onward given birth to a slew of newly personal titles such as Braid . Journey , however, felt different—a video game with levels, an avatar, and enemies, but that, mechanically, eschewed almost all else to focus entirely on movement. The game had cutscenes, but these were reserved for establishing shots of glinting sand rather than moments of genuine dramatic thrust. What Journey achieved—which few, if any, video games had before—was giving you a lump in your throat while you actually interacted with it. This was a big deal.

In this way, Journey helped crystallize the idea that video games could and should be more. In 2007 and 2010, respectively, Bioshock and Red Dead Redemption , games with knotty philosophical questions at their violent cores, had pushed the blockbuster shooter and open-world adventure into newly grown-up territory. But these were also time-consuming experiences that asked you to sink tens of hours into them to get to their narrative payoffs. Journey , by comparison, could be finished in 90 minutes, the length of a film. Certain kids, myself included, grew up convinced of video games’ artistic merit but lacked a work to express this conviction succinctly. Journey was the perfect title to convert churlish nonbelievers—our parents, for example.

I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Gregorios Kythreotis, the lead designer of 2021 indie breakout hit Sable , remembers it like this, too. Kythreotis, who was 19 in 2012, had just started studying architecture, a discipline perfectly suited to the thoroughly spatial medium of 3D games. He was struck by Journey ’s confidence: It was the rare minimalist game whose carefully chosen elements had been executed exactingly. The “biggest thing” he recalls, though, was the fact that he felt he could show it to people who didn’t play video games. “They would play it and often be wowed,” he says over Zoom. “It was a lot friendlier and [more] accessible in this regard.”

Alx Preston, the creator of critically acclaimed 2016 action game Hyper Light Drifter and the recent open-world adventure Solar Ash , tells me over a video call that it was Journey ’s singular style that caught his attention. “There weren’t a ton of games out there that had this type of look,” he explains. “This type of vibe, these types of color palettes, that wasn’t focused on violence or goofy, silly cartoony things. It was carving out its own niche.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23303895/1_1437471569.1.png)

Clayton Purdom, who was then writing at Kill Screen , one of the era’s hip new video game publications, echoes this point. (Disclosure: I wrote for Kill Screen while Purdom was editorial creative director.) “I remember interviewing someone who talked about it as a ‘dinner party game,’” he tells me over a video call. “I’m never gonna have a dinner party where we all sit around and play Journey , but it makes sense. The game’s this really digestible, concrete, audiovisual narrative experience that’s fundamentally interactive.” In 2013, a month before the game’s release, Kill Screen ran the headline : “Is Journey creator Jenova Chen the videogame world’s Terrence Malick?” The comparison doesn’t really land beyond a shared fondness for stirring panoramic landscapes, but the question speaks to a time when many were attempting to frame video games as worthy of serious cultural discussion—as if you’d talk about them with your friends in the same breath as the latest Sundance hit.

Chen, the creative director of Journey , was held up as the poster boy of this movement, and so he was first in line for criticism. In 2010, film critic Roger Ebert wrote a gamer-baiting piece titled “ Video games can never be art .” At the behest of a reader, Ebert was encouraged to check out a TED talk by Kellee Santiago, a cofounder of the studio behind Journey , thatgamecompany. Santiago made an argument to the contrary, referencing, among other games, the studio’s previous title, Flower , in which you play as the wind carrying an assembly of petals. Flower was heralded as a game changer when it was released in 2009, an emotional, nonviolent title that even a novice could play by virtue of its simple controls. (The player tilts the PlayStation 3 controller to change the wind’s direction.) In 2013, it was added to the Smithsonian’s permanent collection and described as “an important moment in the development of interactivity and art.” Ebert, however, took a different view, batting the game away with a typically terse one-liner in which he compared its aesthetic sensibility, not entirely unfairly, to that of a “greeting card.”

When I speak to Chen over Zoom, he doesn’t mention Ebert by name but references the wider discourse. It was a “sense of rebellion” that drove him to make Journey , the idea that games should appeal to an audience beyond the young men who were interested in fist-pumping shooters like Call of Duty . (These games “weren’t actually mainstream,” he says, “they just had billboards on the street.”) Linked to this was the perception of video games in his home country of China as “virtual drugs” that caused people to drop out of college and neglect their relationships.

During the early years of his pursuit of a computer science degree at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Chen snuck into art classes. A few years later, he studied digital art and design as part of a cross-university collaboration with Donghua University. At the time, he and a friend would make video games in their college dorms, Chen art directing and his friend programming. There was little information on video game software available in China, so Chen’s partner learned about game-making from books sent over by a cousin in the U.S. Still, even while Chen was making games as a hobby, he didn’t consider it a viable career path. He intended to become an animation director like those at Pixar. “I felt like that was an industry respected by society,” he says. “I could tell my parents that I wanted to be an artist in this field and they couldn’t say it wasn’t honorable.”

Art as a career was an ongoing point of contention between Chen and his parents. He was born in Shanghai in 1981, five years after the end of the cultural revolution that sought to purge China of its pre-communist art and culture. Despite being an avid drawer, he characterizes his childhood as one devoid of art. Of these early years, he remembers that the sky was always gray except when it had just rained. The dust from the construction sites of the rapidly expanding city would lift and he’d be able to “smell the soil in the air”—for a brief time, “the sky was blue.” In an effort to steer Chen toward “respectable” employment in the modernizing country, his parents enrolled him in a coding class at the age of 10. “In China there was no plan from the government to take care of the elderly. Your kid was your retirement insurance,” he says. Despite initial misgivings about the coding classes, Chen quickly came to look forward to them thanks to the video games his classmates played before lessons.

Chris Bell, a designer on Journey who joined thatgamecompany halfway through the game’s production, says Chen possesses the complete package of skills needed to make video games. “He’s an artist, a programmer, and an engineer,” Bell tells me over a call. Having excelled in programming, Chen rekindled his childhood artistic impulse as a teenager when Shanghai began to open its door to international artists in the 1990s. On the way back from school, he’d stop off at the art galleries in People’s Square. “I would check literally every single show,” says Chen, who savored these “windows to the outside.” When it came to contemporary art, the teenager would ask a central, probing question: “Why does it deserve to be on the wall?”

Fast-forward to 2009. Chen, who had moved to the States six years earlier to study interactive media at the University of Southern California, was wrapping up production of Flower , the second of three thatgamecompany games published by Sony. (The first was a life simulator called Flow .) He was vibing off how people were responding to the game, particularly the finale of its movielike three-act structure, and he was ready to take the lessons learned at USC to the next level. But Zynga had just exploded onto the scene with its interpretation of social gaming, the hit Facebook game FarmVille . Chen remembers watching the company’s CFO give a talk at an industry conference. Having proclaimed the future of gaming as social, the CFO urged indie developers to quit their passion projects and join the company. “Everybody was pissed,” he recalls. “I felt their anger, too. I was like, ‘Who are you? How can you say that you define social games?’” For Chen, social meant an emotional connection between people, not just “trading vegetables with someone on FarmVille .”

This became the seed from which the rest of Journey grew. Chen wanted to show the world a game in which you truly emotionally engaged and connected to another person. It was another “act of rebellion,” against both Zynga’s transactional idea of connection and traditional multiplayer games filled with “foul-mouthed, teabagging” kids. When Matt Nava, the art director on Journey , interviewed to join thatgamecompany in 2008, the first question Chen asked was how he’d approach the social world of Journey : What would it look like, where would it take place, what would happen? Nava, “sweating bullets,” replied, “When you see another player in the game, through the visuals and the setting, you should immediately want to go to them. You want them to be the respite in the environment.”

Nava’s art, both elegantly minimalist and capable of summoning a deep, mythical history, is central to the success of Journey . In the same interview with Chen, Nava suggested brightly colored characters inhabiting a barren desert setting. This would become the game’s defining image. These creatures are humanoid but not identifiably human; they have bright eyes but no other facial features. The world they inhabit is filled with ruinous temples, tombstones, and sand that glints and glitters as if its very surface is dancing. When your character moves over these particles, their pointed legs deform it as if the grains have a physical presence, not just a flat, lifeless texture. Your character’s scarf, flapping in the wind like a ribbon, has a tangible quality, too, another component that tricks you into thinking this is less a computer program than an actual place of elemental forces.

You’re also swept along by Austin Wintory’s rousing soundtrack, which (in lieu of any text or dialogue) functions much like a narrator. “The music is very much a guide for the player,” says Wintory, who admits he felt a huge amount of pressure as a result of the soundtrack’s prominence in the experience. The composer was keen to avoid dictating emotions to players; rather, he wanted to create a musical environment in which they could bring their own “emotional projection into the equation.” Wintory refers to a feeling of “camaraderie” between himself and Nava; the pair would “riff a lot,” almost as if they were in a “feedback loop” with one another.

Nava, whose father is also an artist (the creator of a series of grand tapestries that hang in a cathedral in downtown Los Angeles), says he was obsessed with creating an “iconic” art style . He did so while working within the technical limitations of the PlayStation 3 and, more importantly, what he and the small team could physically produce in the allotted schedule. In the late aughts, out-of-the-box game-making software such as Unity and Unreal (now industry standards) weren’t yet widely used, so thatgamecompany had to build their own set of custom tools. In the early phase of development, Nava and graphics programmer John Edwards went back and forth constantly about what was and wasn’t possible. Ultimately, it was a case of “if you don’t need it, you don’t make it,” so they homed in on the fundamentals of the world: characters, architecture, sand, and fabric.

Despite a strong central idea and a mass of raw talent at thatgamecompany, the production of Journey was challenging. Executive producer Robin Hunicke, speaking five months after the game’s release at Game Developers Conference Europe, referred to a nearly catastrophic level of miscommunication within the team. Bell, who was hired initially as a producer and who later transitioned to a game designer role, took it upon himself to act as a mediator. Some relationships became so fraught that Hunicke described them as breaking down into “personal grudges.” At one stage, Nava arrived at work to find there was already a full-blown argument happening. He quit on the spot, only for Santiago to chase him down the sidewalk and coax him back into the building.

As time wore on, one deadline with Sony passed, and then another. The company’s finances were in such dire straits that Chen and the founding members of thatgamecompany all dropped to half salaries for the final six months of development. Nava says the team fell into the same trap as so many creators who believe that “in order to make great art, it was worth the suffering.”

During a period of acute creative drift, an exasperated Nava took it upon himself to design a level, much to Chen’s annoyance (as lead artist, this was categorically not Nava’s remit). From his perspective, there were a handful of mechanics but nothing was really sticking, so he focused instead on creating a series of “atmospheres” that the player would progress through. Nava thought back to specific “moments” he had in mind when he was painting the concept art, and then fed them back into the levels. The most famous of these sees you hurtling through a stone tunnel while a sumptuous orange sun sets to your right. “Thinking about it as moments was the real trick,” says Nava. “That’s what people remember the game for.”

The gambit paid off. When it was released on March 13, 2012, Journey received rave reviews from outlets such as The Guardian (“the best video game I have ever played”), Eurogamer (“a “sand-blown chunk of spiritual eye candy”), and IGN (“one of gaming’s most beautiful, most touching achievements”). Nava is right to point to the “moments,” which Kythreotis remembers as “a really special aesthetic experience,” as key to its creative success. But the multiplayer is integral, too—arguably an overlooked aspect of the game that to this day breathes an improvisatory life into it. Humans behave differently from AI characters; they move erratically and compulsively, both too slowly and too quickly, and this discord, which takes place against the game’s pristinely melancholic world, is vital to its balance.

Still, the production took its toll on the team. Bell and Nava both exited soon after, citing difficulties relating to the company culture. As Nava explains, they weren’t the only ones: “I don’t think many people fully understand what happened,” he says, “but [thatgamecompany] shut down basically. Everyone left.”

The studio was later revived for the production of 2019 iOS title Sky: Children of the Light , another multiplayer exploration game albeit set amid billowing clouds. In 2017, Bell returned as a designer, noting a broadly positive change in work culture. Chen was now decidedly in charge, whereas before there had been wrangling over decisions between him and his thatgamecompany cofounders. With a bucketload of VC funding rather than a Sony publishing deal, the company had more time and money to explore different ideas. Since then, thatgamecompany has continued to grow. A few days after my conversation with Chen, his company announced a $160 million investment deal alongside the recruitment of Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull, who will serve as principal adviser on creative culture and strategic growth. I suspect a younger Chen would be pleased at this development: a titan of Hollywood animation joining his artistically committed video game studio.

How should one assess Journey ’s influence? It’s not Grand Theft Auto III , a blockbuster behemoth that inspired a deluge of imitators (mostly hyper-violent open-world crime games such as Saints Row ). If you look at the following decade of games, few bear the explicit influence of thatgamecompany’s flagship title. Oceanic explorer ABZÛ and open-world puzzler The Pathless are exceptions, but these were both made by Giant Squid, the studio Nava cofounded in 2013 following his departure from thatgamecompany. Importantly, Journey showed Nava both what games could be and how not to make them, a lesson he carried into his new studio, one built on making “artistic games” in a culture that is “sustainable and happy.”

In a wider sense, Journey helped engender what we’d now call a vibe shift. Put simply, if video games mostly traded in the various emotions related to killing shit, point scoring, or problem solving, Journey was part of a new wave that broadened their dramatic texture. Purdom threads a line between Journey and small-scale interactive works such as Florence , If Found … , and, most recently, puzzle game Unpacking , each of which tells decidedly personal stories. “I think, in some ways, it did help break ground on the whole ‘games are emotional’ angle,” he says. Some titles arguably leaned into sentimentality too hard—2016’s Unravel , for example, an almost unbearably cute platformer starring a yarn of wool. Despite a slew of games Purdom refers to as “feelings porn,” Journey also led to experiences that were, for lack of a better word, more “honest.”

Purdom, however, is rightly wary of ascribing too much importance to Journey . It came out the same year as Gone Home , a first-person exploration game that centers on a queer relationship, and 13 months after Dear Esther , a macabre, William Burroughs–inspired adventure set on a blustery Scottish island. Each was influential in its own way, but the legacy of these games resides more in how they collectively pushed a different emotional, intellectual, and aesthetic agenda to the mainstream. ( Kentucky Route Zero , Cart Life , and Papers, Please are a few of my favorites from the time.) Still, these were all games you had to play on your PC with a keyboard and mouse. Journey , published by Sony for the PS3, “helped kick open the door in a more popular way,” says Purdom. “You could throw that game on and play it on the couch.”

Journey immediately became the fastest-selling game on the PlayStation Network at a time when most titles were still bought in brick-and-mortar stores. For Nick Suttner, who was working as a senior product evaluator in Sony’s third party department, the game was “perfect ammunition.” He and a small team were responsible for getting games onto the PlayStation Store in an era when resources for such titles were highly contested. “We had to fight for everything,” he tells me over Zoom. “Indies just weren’t part of the ecosystem.” The success of Journey fed into what Suttner calls a “holistic push” at Sony, which had also included a three-year, $20 million publishing fund for indie games that was announced in 2011. A year after Journey ’s release, explosive blockbusters Killzone: Shadow Fall , Destiny , and Watch Dogs dominated the PlayStation 4’s glitzy announcement, but amid all the gunfire was The Witness , a serene, first-person puzzle game. It felt like part of a sea change in priorities at Sony that Journey was partly responsible for.

However, Sony’s support for indies wouldn’t last. A few years later, when it became clear that the PlayStation 4 was trouncing the Xbox One, the company’s focus shifted back to blockbuster game development. Sony poured resources into the next generation of megahits, such as The Last of Us Part II , Marvel’s Spider-Man , and Ghost of Tsushima . Along the way, Sony’s Santa Monica Studio, which was both the developer of the God of War series and an incubator and publisher for indie developers, had a game canceled. This meant layoffs on the development side and a deprioritizing of the publishing division that had launched Journey a few years earlier.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23303900/1_1437471570.3.png)

On December 1, 2016, the indie-oriented publisher Annapurna Interactive announced its formation, led by Nathan Gary, the creative director of Sony Santa Monica’s indie development efforts. Chen, who has been variously described as a “scout” and “spiritual adviser” to the company, refers to himself as “more of a cofounder.” Having sourced investment for Journey ’s follow-up, Sky: Children of the Light , Chen was perfectly placed to introduce Gary to potential funders. After securing a deal with Annapurna, itself a film production company behind a string of auterist hits including The Master , Zero Dark Thirty , and Her , attention turned toward signing games. If there was a guiding principle, says Chen, it’s that he and Gary were looking for game makers who were ready to put an aspect of their personal life into the game. Chen describes this as an “innately artistic” approach; the creators are “honest,” saying something that is “truthful to their own lives.” Crucially, these works are more likely to resonate because, as Chen sees it, “our lives are all intertwined.” In other words, we see ourselves in these games.

Chen says Annapurna was also looking for emotional tones underrepresented in games. He mentions 2017’s What Remains of Edith Finch , a game he characterizes by its “dark humor,” and one that his former colleague Bell took a lead role in designing. Maquette , released in 2021, fits the bill, too, a decidedly Hollywood-feeling romantic drama wrapped around a mind-bending puzzle mechanic. In fact, almost the entirety of Annapurna Interactive’s roster is a reflection of the central thesis that has steered Chen’s career, namely that gaming must look beyond the 15-to-35 male demographic if it’s ever going to evolve, let alone be taken seriously.

When I ask Chen about Journey ’s influence on the wider gaming landscape, he doesn’t mention specific titles or trends, but pulls focus back onto the work itself with, to my surprise, an extended music metaphor. “If you want an orchestra to move people, then every instrument has to perform the same piece of music. Every element contributes to the storytelling,” he says. “And what we learned is that the interactivity is the soloist. It’s the lead of the orchestra in gaming. A lot of games in the past have told emotional stories— Final Fantasy , for example—but they relied on traditional media. I love it, but the moving part, the part where you cry, is when you watch the cutscenes. At that moment, what really touched you is cinema, not games.”

In a way, it’s surprising how few blockbuster games have internalized this lesson. The recently released Horizon Forbidden West is a good example. When I play that game, it moves me, but mostly because of the sense of awe I feel at its shimmering, windy world . It’s the same for Ghost of Tsushima and the Uncharted games. That’s not to deny the validity of these experiences, but their moments of personal drama are delivered without the player’s input. Journey , in its own very specific way, figured out how to make drama interactive. Purdom refers to Signs of the Sojourner , an indie card game about friendships and conversation, as a “next step” in this regard. “It’s a mechanically complex game entirely in service of inspiring these kinds of emotional experiences,” he says. “It’s like, ‘Wow, I’m feeling regret because I hurt a friend’s feelings thanks to the way these cards played out.” My own mind is drawn to Hideo Kojima’s postapocalyptic hiking simulator, Death Stranding , and the grueling slogs my character endured through snowy mountains. These interactive journeys mirrored the protagonist’s emotional arc, and each landed with greater heft as a result.

This is the magic of Journey . At the start, you move tentatively but curiously. In the mid-game, you’re cascading down dunes at extreme speed. And during the very lowest moments, you’re barely making a step at a time. Then, when you have nothing left to give, you stop moving entirely, however hard you push forward on the controller. “What Journey did really well,” says Chen, “was to make interactivity the climax—the memorable moment.”

Lewis Gordon is a writer and journalist living in Glasgow who contributes to outlets including The Verge , Wired , and Vulture .

‘Fallout’ Season 1 Reactions

Weekend watches, ‘the sympathizer,’ and ‘fallout’, hbo shows on netflix. xbox games on playstation. is exclusivity over.

Why Journey is one of the greatest games ever made

Redefining movement

Here's what you need to know about Thatgamecompany's Journey: It's short. It's got kind of an exploration-heavy puzzle-platformer vibe, with splashes of adventure game. What else? It's pretty, it sounds good. Oh, and it understands human emotion on such a basic, fundamental level that it knows how players will react to any given situation, and respond accordingly. Every developer, irrespective of their discipline, can learn from it, and every person is better off for having played. It signifies a watershed moment for the game industry; it is our Citizen Kane . All of this is to say, Journey's easily one of the greatest games ever made.

Editor's note: Journey is best experienced with little to no prior knowledge of it. If you haven't yet played this game, may we suggest bidding adieu to GamesRadar, booting up your PS3, and we'll see you again in a couple of hours? Great.

One of Journey's greatest achievements is the way in which it redefines movement, that basic and original tenet of games. In many ways, Journey is a game about movement--a palpable traversal of environments to elicit emotion--and this is evident from the get-go. Journey's opening sequence drops the player at the foot of a sand dune. A hill must be climbed, and as you ascend, a toil sets in for each step taken.

When you reach the summit, two things happen. First, you see an intimidating expanse situated between you and a majestic mountain, the climbing of which puts your current accomplishment to shame. The second thing you notice is that your movement is unencumbered, a feeling made all the more delightful as you speedily zip down the other side of the hill. So just to review, there's feelings of hardship, accomplishment, satisfaction, awe, foreboding, delight, and curiosity, all from just walking up one side of a hill and sliding down the other.

Journey's also an aesthetic masterpiece, from a purely technical perspective. However, calling out the quality of its textures or music is to miss the genius--the way sight and sound couple with movement to further heighten and convey emotion.

There is the above example, yes, but take for instance a sequence early in the game, where you find yourself sliding down a hill at an increasingly alarming rate, unable to slow or stop. Around you fly ethereal beings, eagerly urging you along in your descent. You hit a tunnel, and the camera flips to a side-scrolling angle. The color palette transitions to darker, lusty reds, and your mountain goal appears, closer, illuminated like a beacon by the sun. You feel swept away, excited, joyous, and also a bit fearful over the loss of control. You think of the first time you fell in love.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Current page: Page 1

After 18 years, PlayStation's year-round E3 trailer resurfaces on Facebook Marketplace for $70,000, from a vendor who apparently has no idea what they're selling

And just like that, one of the most beloved JRPG series out there gets even harder to play: multiple Tales games have been pulled from the PlayStation Store

In less than 3 hours, Hades 2's new and returning characters have already put the entire fandom in horny jail

Most Popular

Follow Polygon online:

- Follow Polygon on Facebook

- Follow Polygon on Youtube

- Follow Polygon on Instagram

Site search

- Dragon’s Dogma 2

- FF7 Rebirth

- Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

- Baldur’s Gate 3

- PlayStation

- Dungeons & Dragons

- Magic: The Gathering

- Board Games

- All Tabletop

- All Entertainment

- What to Watch

- What to Play

- Buyer’s Guides

- Really Bad Chess

- All Puzzles

Filed under:

- Journey and the search for emotional gaming

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Journey and the search for emotional gaming

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/7824903/jenova_chen_dice_2013.0.jpg)

Journey is a game of catharsis, a hero's journey. A game that spurred emotional emails from fans and nearly destroyed the company that made it.

Speaking at the 2013 DICE summit, thatgamecompany co-founder Jenova Chen said that Journey started out as a simple idea in 2006: catharsis.

Chen had grown disenchanted with how emotionally simplistic and repetitive most games were. Games often served to fulfill the emotional needs of a younger male audience, giving them a sense of empowerment and freedom. But Chen said thatgamecompany was created to deliver emotional experiences, specifically to deliver catharsis through emotional play.

Earlier in the day, Chen told Polygon that the first game the group created while at USC's Interactive Media Program was inspired by that idea.

"Each game we worked on were based on psychological theories and three act structures," he said. "Our goal is to touch people and help people reach a cathartic moment."

Each of their creations, he said at the time, took a different approach to achieving that moment.

Cloud pursued a sense of calm. Flower was about love. Journey , he said, was about the connection people form with one another in their journey through life.

During his talk, Chen said that it was after flow and Flower that he decided to try to tackle the problem of online gaming and use that to pursue a cathartic moment empowered by those interpersonal connections.

In trying to identify that emotion that he called "connection," Chen said he did some market research. That's when he ran into the astronauts, two men who described to him the experiences of the people who traveled to the moon and back.

One told him how changed those few were, they were more spiritual and more philosophical. The reason, Chen came to believe, was because while on the moon they were freed from distraction and left more emotionally charged and introspective.

That notion helped shape some of the design of Journey . Chen returned to his ideas for the game and worked to strip away as many distractions as possible in order to create a focused experience.

"There is no HUD," he said. "It is a very simple. There is no lobby."

Thatgamecompany then stretched that pure visual experience over the game's levels, designed to loosely follow not just a three act structure, but the monomyth. The idea, he said, is that the journey of Journey has to include a peak, a valley and then a cathartic-delivering final moment.

Chen said the company played around with different forms of multiplayer gaming before settling on a system that allowed players to game together anonymously, but still somehow form a connection with one another through their shared experiences.

After the first year of development, Journey's basic structure and look was sound, but neither were where thatgamecompany wanted them to be. After the second year the game was visually ready, but Chen said the valleys and peaks of their journey were too shallow to deliver any sort of emotional connection to gamers.

The studio decided to spend another year on the game, burning through the reserves of their money as they worked out the kinks of their game and tweaked the experience.

"A lot of people weren't paid," he said. "We also went bankrupt as a company."

The experience left Chen wondering whether Journey was worth it's own journey. The answer, he said, came in the 824 emails the company received after the game was released. Many were very personal, very emotional letters to the developer.

He ended his talk by reading one aloud:

"Your game practically changed my life. ... It was the most fun I had with him since he had been diagnosed. ... My father passed in the spring of 2012, only a few months after his diagnosis. Weeks after his death, I could finally return myself to playing video games. I tried to play Journey, and I could barely get past the title screen without breaking down into tears. In my dad's and in my own experience with Journey , it was about him, and his journey to the ultimate end, and I believe we encountered your game at the most perfect time. I want to thank you for the game that changed my life, the game whose beauty brings tears to my eyes. Journey is quite possibly the best game I have ever played. I continue to play it, always remembering what joy it brought, and the joy it continues to bring. I am Sophia, I am 15, and your game changed my life for the better."

"Because of this email," he said, "I think it's all worth it."

In This Stream

Dice 2013: the announcements, interviews and awards from the first big games show of the year.

- Words with Friends creator believes Ouya will usher in a new era for living room gaming

- Warren Spector: 'I'm not ready to retire yet'

The next level of puzzles.

Take a break from your day by playing a puzzle or two! We’ve got SpellTower, Typeshift, crosswords, and more.

Sign up for the newsletter Patch Notes

A weekly roundup of the best things from Polygon

Just one more thing!

Please check your email to find a confirmation email, and follow the steps to confirm your humanity.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Hades 2 gods somehow even hotter than Hades gods

Learn more about the Inner Sphere than you ever wanted to know with this $30 Battletech bundle

Star Trek: Lower Decks’ creator is turning Sega’s Golden Axe into an animated comedy

The Homeworld 3 Collector’s Edition is an epic tribute to a strategy classic

Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy is getting a TV series adaptation

Shōgun episode 9 changed the trajectory of the show

10 years later, the best video game about nothing still lives up to the hype

A simple, beautiful adventure brought harmony to PS3 players around the world.

Seinfeld is famously a show about nothing. Obviously, there’s content on the show, but at the time of its release, every ’90s sitcom had some sort of gimmick. A show about funny people just being friends went against commercial trends. These same trends stifle gaming creators too. Are there any games that broke with conventional wisdom? Did time prove them right? Yes and yes — and one of the most noteworthy instances of this just turned 10.

Journey from thatgamecompany took the world by surprise when it was released on March 13, 2012 because it was, on the surface, about nothing. There’s no dialogue, no clear plot, and no token objectives. Yet the atmosphere and level design are so compelling that the game won the hearts of millions (and its fair share of GOTY awards, too).

Journey broke through during a deeply formulaic era of gaming. A look at the top-selling games of 2012 reveals nothing but 2s, 3s, 4s, and annual franchise staples. You could set your market forecast by Call of Duty , Madden, and others. There was Battlefield 3 , Elder Scrolls V , and Mass Effect 3 .

And then there was Journey .

Indie gaming had been steadily gaming Steam (pun intended) since the late 2000sm and releases like Minecraft and Braid showed the potential for well-developed, innovative titles. Along with Steam, Xbox Live Arcade became an important marketplace for indie developers.

Journey takes place in a series of sandswept ruins.

Sony didn’t have the indie support it does now but knew enough to let talented creators experiment by thinking outside the box. Journey was easy to underestimate. There’s no dialogue, no clever plot twists, no shooting or looting or gold. But it’s a shining example of how pure design can shatter expectations for what games should be to show us what they could be, instead.

The magic of Journey is in its aesthetic. Players begin the game in a sweeping desert landscape littered with ruins. The only objective is from a brief cutscene showing someone, something off in the distance dominated by a huge mountain.

So you move. And this is where Journey begins to hook you immediately. It just feels so good . Something about gliding over the wind-whipped sand dunes and skittering up crumbling staircases feels soft and precise. You float and fly along with one of the greatest original soundtracks of all time.

This was the first video game soundtrack to get nominated for a Grammy, and Austin Wintory’s orchestral genius remains a gold standard to this day. (If you’re a hardcore audiophile gamer, the OST is getting a vinyl re-release from iam8bit to celebrate the occasion). In many ways, Journey affirms the power of music as a narrative device, so don’t play it on shitty headphones.

Journey ’s OST is an all-timer.

Players also found meaning in the engaging, but minimalist, multiplayer. You don’t do matchmaking or lobbies. Instead, you encounter other players at random and travel from discovery to discovery together.

In choosing emotional depth over violence , Journey forged thousands of core memories for gamers who had never experienced anything together besides conflict and competition. Conventional multiplayer pits gamers against each other, Journey puts them together instead.

Journey is available on PC and the PlayStation Store, where it's currently on sale .

- Video Games

- PlayStation

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Journey and the Semiotics of Meaningful Play

The term "meaningful play" had entered the gaming vernacular in recent years, particularly in conjunction with independently developed ("indie") videogames, but little to no consensus still exists among scholars and gamers as to what exactly makes an act of play "meaningful". In order to approach this question from a scientific and analytical perspective, the present study borrows the methodology and concepts of semiotics, the formal study of signs and meaning-making, and applies them to Journey, a popular videogame lauded by critics for facilitating meaningful player experiences. The study builds upon the ludic framework, a semiotic theory of meaningful gameplay currently in development by the French videogame researcher Frederic Seraphine, and consists of two parts. First, we give a brief overview of the three key theories underlying Seraphine's work (the semiotic studies of Charles Peirce and his students, the cybertextual studies originating with Espen Aarseth, and the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics framework), before examining the ludic framework itself in detail. We then analyze the production background and history of Journey and perform a semiotic analysis of select elements of its visuals, mechanics, and levels in an attempt to better understand its way of creating meaningful player experience. Finally, we draw conclusions both about the applicability of semiotic analysis to contemporary games and about the question of meaningful play itself.

Related Papers

Frédéric J N Seraphine

Using concepts from semiotics, aesthetics, and ludology, this paper is shaping a framework opening new perspectives on meaning and emotion evocation in videogames. While building upon the MDA Framework, it poses the problem of meaning production in game design when the traditional building block, the game mechanics, is a complex rule-based semiotic compound belonging to the Peircean thirdness. It proposes an alternative building block called the ludic at a higher level of abstraction, allowing for wider combinatory possibilities and deeper meaning production through the gameplay itself. It introduces an interpretation layer opening new possibilities for both narrative and emergent gameplay.

Expanding Practices in Audiovisual Narrative

Oliver Laas

Broadly speaking, digital games can be studied in three ways: the social sciences perspective focuses on the social context of games and their players; the humanities perspective takes games as cultural artifacts, and concentrates on their meaning as well as ways of meaning-making; and the design perspective views games as a set of design and programming problems. What distinguishes digital games from traditional ones like chess is their greater emphasis on representational and narrative elements. From the humanities perspective this raises a number of questions. What is the scope of literary theory and narratology in the game scholar's methodological toolbox? How should computer games as objects of study be defined? In the early years of game studies these questions were at the heart of the so-called "ludology versus narratology" debate. I believe that revisiting the debate could be edifying for humanities scholars working in adjacent areas. Additionally, while contemporary research tends toward more holistic approaches, as far as I know extant accounts of how narratives and game rules are intertwined have either reduced games to non-trivial cybernetic machines or interactive semiotic matrices, restricted themselves mostly to the expressive aspects of games, or left the interrelation between rules and narratives ultimately somewhat vague. After reviewing the ludology vs. narratology debate and some of its central points of contention, I will propose a holistic account of the relationship between games and narratives. Narrative will be treated as a cognitive strategy for making sense of the game's fictional world that is created by the rules of the game via semiotic means. Instead of reducing games to other kinds of entities, it will be shown that games qua games are the source of the semiotic processes which ultimately create fictional worlds and direct the player toward a narrative interpretation of the game's signs.

Sebastian Möring

This doctoral dissertation critically investigates how the concept of metaphor is used with regard to games in game studies. The goal is to provide the field with a self-understanding of its metaphor discourse which has not been researched so far. The thesis departs from the observation that the notion of metaphor has been present in the discourse of game studies since it emerged as an academic field and focuses on questions such as: What are the motivations and effects of calling games metaphors in the game studies discourse? Which problems arise from that with regard to other established concepts in game studies such as simulation and procedural rhetoric? How do concepts and insights of contemporary metaphor theory affect the applicability of the notion of metaphor with regard to games? Drawing on concepts from metaphor theory (in particular the cognitive linguistic view on metaphor), play and game theory, cultural theory, semiotics, linguistics, philosophy, and game studies it investigates the metaphor discourse of game studies in the fashion of a meta-study. The main part of this thesis is devoted to three particular problems which have been derived from observations in the overview of the current use of the notion of metaphor in game studies. Firstly, this thesis investigates is the conceptual relationship between the notions of metaphor, representation, and play. It therefore accounts for observations such that all three notions are present in non-computer game and play theory, theory of representation and art which all influenced game studies and argues for an equiprimordial relation between these three concepts. Secondly, this thesis deals with what is termed the metaphor-simulation dilemma which accounts for the observation that in game studies the notion of metaphor is very often used in close conceptual proximity with the concept of simulation to the extent that they become conceptually indistinguishable. The two notions are reconciled through the notion of the model and a case study will demonstrate that it is possible to think of simulations as based on metaphorically structured models. Thirdly, thesis deals with the observation that the concept of metaphor is referred to in game studies in particular when games are interpreted in terms of some existential topic. Usually addressed from the perspective of (procedural) game rhetoric games are called metaphors for struggle, life, death, love. On the basis of a criticism of procedural rhetoric this thesis will suggest a distinction between a textual hermeneutic and an existential hermeneutic of games in which the latter is primary. It suggests furthermore that metaphoric interpretation of games is usually a sort of text interpretation. This supports the argument of a general de-metaphorization of alleged metaphoric computer games.

This thesis is a critical examination of videogame theory and of videogames. The analysis of various approaches to videogames, from ludology to unit operations and simulation, places each approach alongside each other to compare and contrast what is gained and lost by adhering to each perspective. Following from this, I develop a framework which considers the role of the player as part of the game system, whose attitude will influence their relationship with the videogame. Critics must acknowledge and respect the varied play practices of various kinds of players in exploring what any given videogame means. Finally, I explore three broad videogame-play experiences: ludic play, narrative or dramatic pleasure, and paidic curiosity and exploration. Each of these offer fundamentally different ways of addressing videogames as objects and the play of games as a practice, which creates a more nuanced language with which to discuss various kinds of videogames and experiences of play. Through close studies of a range of contemporary, mainstream videogames, I conclude that not only are there fundamentally different kinds of videogames which cannot all be adequately served by a single approach, but that players utilise different approaches themselves when playing. Therefore, videogame theory should become at least as varied and agile as videogame players themselves. The goal of this thesis is to explore what certain games mean, to certain players, rather than appeal to a higher, objective sense of true, universal meaning.

Víctor Franco

En el presente ensayo se efectúa un estudio exploratorio de los denominados Game Studies y de otras disciplinas de estudio de la narrativa, para así partir en busca de una metodología útil que relacione satisfactoriamente los espacios narrativos y los de interacción en videojuegos. Como muchos teóricos de la ludología y la narratología apuntan, la relación entre la narrativa y las posibilidades de interacción es un tanto difícil en los textos videolúdicos. Muchos de estos teóricos, han incluso propuesto separar ambas estructuras semióticas, en pos de no incurrir en ciertas prácticas desagradables para el usuario: las disonancias ludonarrativas y las disonancias cognitivas. La relación ambivalente que se concibe como clave para entender la emergencia de estos sucesos a evitar, es la denominada como agency, que a groso modo es la posibilidad de cambiar el sistema de juego. Encontrar la forma de potenciar esta capacidad mediante la narrativa es la mejor forma de evitar el distanciamiento que corresponde a las temidas disonancias.

Game love: essays on play and affection

Recently published, abstract flash and browser games such as Love (2010), The Marriage (2006), My Divorce (2010) can be summarized as games about love. As opposed to simulation games such as The Sims 3 (2009) in which the topic love is more or less realistically depicted the given abstract games consist on the semiotics level mainly of geometrical forms like squares and circles which move through the gamespace in a certain manner according to in-game events and player inputs. Mainly the titles of the mentioned games reveal their topic as games about love or love relationships. This incongruity between the title and the dynamic system of geometrical shapes seems to be a paradox at first sight which provokes a reflection on the relationship of the topic of these games and their semiotic properties as well as their rules and represented mechanics (Aarseth 2003, Sicart 2008). In terms of the ontological game love model by Jessica Enevold (2010) this paper contributes to the section “love in games” since it is especially interested in the way in which the theme of love is modeled in the examples or why it can be projected on them. To identify love in the described abstract games I will use the approach of cognitive linguistic metaphor theory according to which love in everyday western languages is to a large part understood in terms of space. The centrality of the love theme in the chosen examples as well as its graphical and mechanical minimalism will provide a rare counter perspective to games which usually operate with more naturalistic simulations of love phenomena like Heavy Rain, The Sims 3 or apply specific romance mechanics during the game like e.g. Dragon Age (c.f. Waern 2010) or Mass Effect. This paper makes the reader aware that there is a comparatively small and peripheral group of games which investigate the topic of love with very simple and abstract means which do consequently not result in a naturalistic simulation but in a playable concept of love. Thus, this contribution will focus on love as an abstract concept and its realization in games. It helps to understand game love as being influenced by an everyday understanding of love as it is always already pre-structured by the mostly conventional metaphors we use to talk about it as opposed to philosophical concepts of love. The leading research questions to be answered in this article are: How can the mentioned games be understood as games about love? Are they love simulations, love metaphors or simulations of a metaphorically structured concept of love? Discussing the first two options, especially the last notion will be emphasized. To tackle these questions, this article will discuss and analyze the mentioned games. It will make use of different definitions of the term simulation from the field of game studies as well as from natural and social sciences such as Frasca (2001, 2003), Juul (2005), Bogost (2007), Begy (2010) and Hartmann (2005). Furthermore, it will apply a notion of metaphor derived from the cognitive linguistic metaphor theory by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson (1980, 1999) which considers the human ability of metaphorical reasoning as a fundamental structure of thought and experience which results from our bodily being in the world. In doing so the article will in addition discuss earlier explicit approaches on metaphor in (abstract and non-abstract) computer games as there are Madsen and Johansen (2002), Rusch (2009) Begy (2010) and specifically on love metaphors in games like Rusch and Weise (2008). However, it will criticize especially earlier approaches by Rusch (2009) and Begy (2010) who consider the games to discuss not as metaphors but for instance as simulations of love relationships only. To strengthen the argument that the given games can be considered as simulations of our metaphorically structured concepts of love this article will refer to empirically grounded cognitive linguistic research on commonly used metaphors for love such as Kövesces (1988, 2003, 2010). According to Kövesces love is understood in terms of conceptual metaphors such as LOVE IS A UNITY OF PARTS, LOVE IS CLOSENESS, and LOVE IS A BOND. It will become apparent that especially metaphors which conceptualize love in a spatial manner are appropriate to describe the game states of the given games and make their theme comprehensible. As the distinguishing feature of computer games as opposed to other forms of media is their spatiality (Aarseth 2000, Wolf 2001, Nitsche 2008, Günzel 2010) one can conclude that games can implement an abstract topic like love especially through the implementation of its spatial characteristics.

Clara Fernandez Vara

In the problematic exploration of the narrative potential of videogames, one of the clearest aspects that bridge stories and games is space. This paper examines the different devices that videogames have used to incorporate stories through spatial design and what is known as environmental storytelling, focusing on the design elements that make the story directly relevant to gameplay beyond world-building and backstory exposition. These design-related elements are accounted for with the term indexical storytelling. As a refinement of the concept of environmental storytelling, indexical storytelling is a productive game design device, since reading the space of the game and learning about the events that have taken place in it are required to traverse the game successfully. Storytelling becomes a game of story-building, since the player has to piece together the story, or construct a story of her own interaction in the world by leaving a trace.

Gianmarco Thierry Giuliana

In this paper I propose a unifying perspective on meaning-making based on the assumption that signification in digital games is mainly produced through the cognitive & interpretative processes involved into gameplay. More exactly, the gameplay will be intended as series of sensorimotor acts and cognitive tasks that act as a catalyst and hub between semantics, narration, aesthetic, interactions & mechanics. This will be done with an interdisciplinary case analysis of Brothers: a tales of two sons and Papers, Please. My goals are two. The first one is to offer a deeper perspective on how complex contents, like brotherhood as a value and migration as a topic, dramatically depend on the cognitions triggered by playing that act as signifiers for interpretations on all the different layers of meaning. The second one is to contribute in laying the foundation of a unified perspective of meaning.

The notion of dialogue is foundational for both Juri Lotman and Mikhail Bakhtin. It is also central in Charles S. Peirce's semeiotics and logic. While there are several scholarly comparisons of Bakhtin's and Lotman's dialogisms, these have yet to be compared with Peirce's semeiotic dialogues. This article takes tentative steps toward a comparative study of dialogue in Peirce, Lotman, and Bakhtin. Peirce's understanding of dialogue is explicated, and compared with both Lotman's as well as Bakhtin's conceptions. Lotman saw dialogue as the basic meaning-making mechanism in the semiosphere. The benefits and shortcomings of reconceptualizing the semiosphere on the basis of Peircean and Bakhtinian dialogues are weighed. The aim is to explore methodological alternatives in semiotics, not to challenge Lotman's initial model. It is claimed that the semiosphere qua model operating with Bakhtinian dialogues is narrower in scope than Lotman's original conception, while the semiosphere qua model operating with Peircean dialogues appears to be broader in scope. It is concluded that the choice between alternative dialogical foundations must be informed by attentiveness to their differences, and should be motivated by the researcher's goals and theoretical commitments.

Digital children’s literature is a relatively recently established field of research that has been seeking for its theoretical base and defining its position and scope. Its major attention so far has been on the narrative app, a new form of children’s literature displayed on a touchscreen computational device. The narrative app came into being around 2010, and immediately attracted the attention of the academics. So far, various studies have been conducted to explore its educational potential, but very few have investigated the app for what it is in its own right. To bridge the gap, this study has explored the nature of the narrative app and the essential principles of its narrative strategies. As the subject of this study concerns a variety of disciplines, this research has been conducted in an extremely interdisciplinary way in order to develop a thorough understanding of the narrative app. In general, it has consulted scholarship in children’s literature (picturebook studies in particular), narratology, computer science, game studies, social semiotics, film studies, media studies, communication studies, electronic literature and game design. With this interdisciplinary approach, this study has attempted to define the subject of the study, identify some tendencies in its development, and most importantly, develop an original theory of storytelling and a narrative map that may be able to explain the intrinsic methods used in the narrative app storytelling as well as other digital and non-digital storytelling. The findings of this study seem to suggest that the narrative app does not display any essential differences from the codex and other forms of literature in terms of its narrative strategies, but it appears to have great potential to truly innovate storytelling. It is suggested that this study may provide an effective theoretical scope and methodology for the study of the field of digital children’s literature, which may offer the potential to strengthen this field of research. The theoretical framework constructed by this study may be applicable to some educational approaches to the narrative app, and may also be useful for teaching new literacies.

RELATED PAPERS

Agata Meneghelli

Jef Folkerts

Digital Games and Learning

Ernane R . Martins

Tim van Leeuwerden

Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies

Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies Journal

Rudy McDaniel

Veli-Matti Karhulahti

MedieKultur. Journal of media and …

Patrick J Coppock

Luthfie Arguby

Cameron Kelly

Mihai Nadin

Ahti Pietarinen

Martijn Kors , E.d. Van Der Spek

Playing Dystopia: Nighmarish Worlds in Video Games and the Player's Aesthetic Response

Gerald Farca

Videogame Studies: Concepts, Cultures and Communication

Tobias Unterhuber

Sonia Fizek , Paolo Ruffino

Paul Formosa

Niklas Schrape

Journal of Games Criticism, 2 (1)

Ricardo Gudwin

Games and Culture 10 (2)

Dusan Stamenkovic , Milan Jaćević

Semiotics and Intelligent Systems Development

Phyllis Chiasson

Tom van Nuenen

Filipe Pais

Ave Randviir-Vellamo

Sam AlIraqi

Robert Cassar

Phillip Penix-Tadsen

Sonia Fizek

Inna Semetsky

Miguel Cesar

Anttoni Lehto

Kelly Boudreau

Vincenzo Idone Cassone

Douglas W Brown

Adriano D'Aloia

Søren Brier

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Geekwave

Journey and Visual Storytelling

Caroline Henry May 27, 2021

When it comes to story, many games focus on dynamic characters, interesting dialogue, and amazing voice acting. These three things became a huge part of video game storytelling. However, Journey threw all of that out the window. The developers, Thatgamecompany and Santa Monica Studio, decided that the main focus regarding storytelling would be visuals, and they pulled it off incredibly well. Journey shows this through combining a beautiful atmosphere and engaging deep storytelling to create adventurous areas with scrolls that hold the past.

Keep Moving Forward

Though it is never specifically said, it’s clear that the goal of the game is to make it to the top of a mountain.

The mountain is captivating whenever it appears. It acts as a lighthouse calling for you while you traverse through each area. The mountain is a beautiful and domineering sight. As a result, the indoor areas are unnerving. You no longer know how close the mountain is, its light is hidden, and you must make your way blindly. This atmosphere of being lost in the unknown encourages you to find the light again, to find the mountain again. In tandem, outside areas are much more calming as they visually show your progress, with the mountain getting closer as the game progresses. You’re motivated to move forward to find what’s at the top and uncover the mountain’s meaning.

There never is a clear explanation given to the player for your motivation to reach the mountain or what waits for you there. However, the sight of the mountain makes you motivated to keep moving forward.

A Sense of Adventure

The best part of Journey ’s storytelling is that the visuals really sell how dynamic your adventure is. You can glide through the eight areas: The Beginning, The Bridge, The Desert, The Descent, The Tunnels, The Temple, The Mountain, and The Summit. Different types of fabric creatures help you gain momentum to launch into the sky. The longer your scarf is, the more time you can spend in the air. Not only that, but each area acts differently. One moment you’re sand skating through breathtaking environments. The next, you’re in a watery-like underground with large, floating enemies that attack you if you cross their line of sight. You’ll find yourself on an upward climb through an ancient temple, then trudging through heavy snow, taking cover from snowstorms. Every area brings something new. This variety exemplifies the sense of adventure on your journey to the mountain across different biomes.

The Present Mimics The Past

To move from area to area, you’ll notice structures that you must light up. This lights up a circle for you to rest and meet a mysterious figure. Who is this mysterious figure, you ask? Honestly, I don’t have a clue. What I do know is that the figure importantly fills in the illustration on a historic scroll. This red scroll fills with gold and white art as you awaken each shrine. Surprisingly, the illustrations reveal the area you just completed surrounded by people that look like your character. It’s like the game is telling you that you’re walking in the footsteps of your ancestors. A sense of connectedness overtakes you as your struggle turns into a meaningful quest. You’re becoming a part of the history of traversing to the mountain.

Journey went the rarely explored route away from conventional dialogue storytelling and became much better for it. The mountain is visually powerful but also a comforting sight. It’s a symbol of completion that catches your eyes whenever possible. With a clear goal in sight, the game makes sure your adventure is enjoyable. The dynamic environments mixed with stunning visuals elevate the sense of achievement at the end. You get to experience past adventurers’ feelings and obstacles, which makes the replayability more sentimental. Journey ’s visual storytelling shines through the mystifying mountain, atmospheric venture, and the sense of unity with the past.

- game review

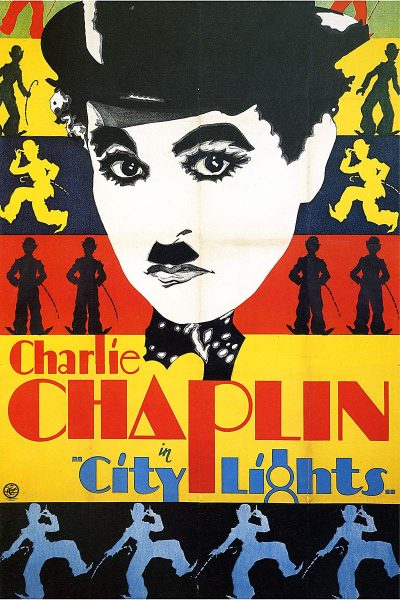

City Lights – Review

April 17, 2024

Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel – Review

April 13, 2024

My experiences/reactions at GDC 2024!

April 5, 2024

Cities Skylines 2 – Review

March 30, 2024

Jade City by Fonda Lee

March 25, 2024

These Violent Delights: A Novel by Micah Nemerever

March 20, 2024

The Dragon Republic by R.F. Kuang

March 16, 2024

Helldivers 2 – Review

March 11, 2024

View this profile on Instagram Geekwave @ UofU (@ the_geekwave ) • Instagram photos and videos

Light Bringer by Pierce Brown

God of War 4 Valkyries Ranking Based On Norse Mythology

Review- The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang

Cities Skylines 2 - Review

Rainbow Six: Siege is Terrible for Beginners

How can we protect Young Readers Online?

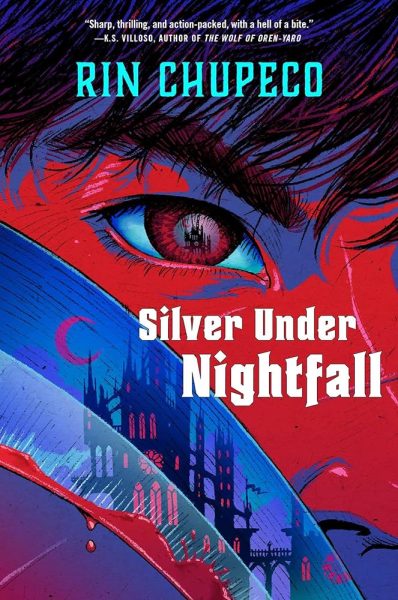

Silver Under Nightfall

Prince of Persia Review

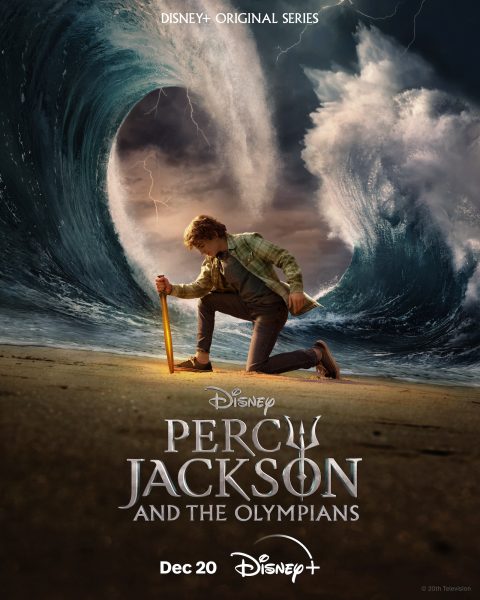

Percy Jackson and The Olympians Season One

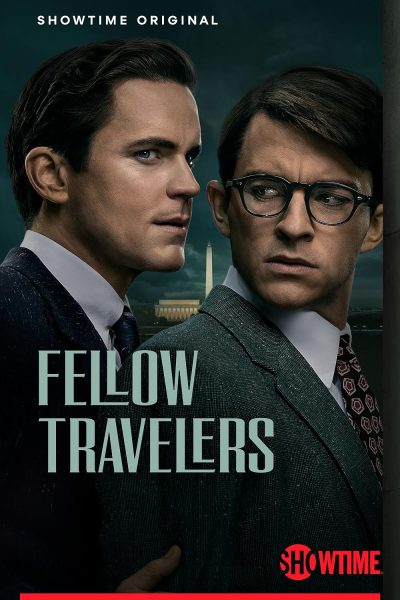

Fellow Travelers TV Show

University of Utah

- Video Content

- Join the team!

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Movies & TV Shows

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Is Journey a game or a piece of interactive art?

I n the 1960s, the pioneering British artist Roy Ascott became fascinated with the possibilities of the telecommunications network as a conduit for his work. He had long been interested in the idea of cybernetics and human-machine interfaces, but as the internet emerged, he saw in it, the possibility of a new form of interactive art, in which groups of distant participants would be able to collaborate in online projects.

Later he coined the term telematic art to describe artworks constructed with telecommunications networks as their medium. The most famous example is his 1983 work, La Plissure du Texte, which arranged for a group of artists in different places around the world to collaborate, via the internet, on an emergent narrative, each contributing a section of a story to an online work, none having an overall vision of where that story may lead. Some of the collaborators may have known each other, others wouldn't, but all they shared was a string of words appearing on their separate terminals – a tale emerging seamlessly from the web.

Fast forward 20 years and we have Journey, the latest release from experimental LA studio thatgamecompany . If there's one thing most game critics can agree on, it is that you must experience it. This ethereal wonder – part adventure, part meditation on life and death – is one of the most fascinating mainstream video game releases of the decade; not as much for its content (which is beguiling enough) but for what it actually is.

And what it actually is, is the key question. Because, by generally accepted definitions of the word, Journey is not a game. It has no fail state: although there is perceived peril, it seems impossible to actually "die" while playing. There is no time limit, so solving puzzles has no sense of tension. And although the presence of puzzles suggests challenge and therefore a game-like experience, these tasks are simple and toy-like.

Players cannot compete for resources or physically interact (the collision detection was apparently removed so that participants couldn't knock each other off walkways). Although there is exploration, the experience ends inevitably with one conclusion – though of course, that conclusion can be interpreted differently by each player.

So what is it?

Well, thatgamecompany continually refers to Journey as an experiment. When I interviewed the producer Robin Hunicke last year, she was very clear about that. Aware that they'd never produced a game with a traditional multiplayer component before, the studio set about exploring the meaning and conventions of online interaction, and sought to manipulate them to create something more spiritual and reflective. All thatgamecompany titles are effectively a Voight-Kampff test – they are designed specifically to provoke an emotional response. And in this sense, they are more like art than games.

That's what Journey is. A work of interactive art. Through its gorgeous emotionally resonant soundtrack, its looming symbolic landscapes, its exploration of interactivity and telepresence, it wants us to ask questions and experience feelings, without necessarily having to engage with game-like structures. It has more in common with the works of, say, interactive art collective Blast Theory, than it does with Modern Warfare or other traditional online games.