- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

Matthew S. Schwartz

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered. Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered.

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

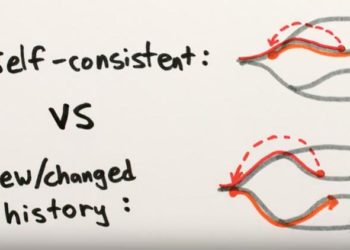

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

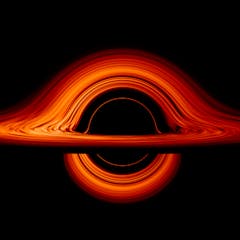

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

- grandfather paradox

- time travel

Articles on Time travel

Displaying 1 - 20 of 25 articles.

Is time travel even possible? An astrophysicist explains the science behind the science fiction

Adi Foord , University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Are black holes time machines? Yes, but there’s a catch

Sam Baron , Australian Catholic University

What are wormholes? An astrophysicist explains these shortcuts through space-time

Dejan Stojkovic , University at Buffalo

Curious Kids: is it possible to see what is happening in distant solar systems now?

Jacco van Loon , Keele University

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Peter Watson , Carleton University

Curious Kids: what would happen if someone moved at twice the speed of light?

Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Barak Shoshany , Brock University

Why does gravity pull us down and not up?

Mario Borunda , Oklahoma State University

New warp drive research dashes faster than light travel dreams – but reveals stranger possibilities

Curious Kids: is time travel possible for humans?

Lucy Strang , The University of Melbourne and Jacqueline Bondell , Swinburne University of Technology

Rotating black holes may serve as gentle portals for hyperspace travel

Gaurav Khanna , UMass Dartmouth

The great movie scenes: Back to the Future

Bruce Isaacs , University of Sydney

Time travel is possible – but only if you have an object with infinite mass

Stephen Hawking’s final book suggests time travel may one day be possible – here’s what to make of it

Peter Millington , University of Nottingham

Like a TARDIS in your head, memory helps you travel through time

Alice Mason , The University of Western Australia

Time travel: a conversation between a scientist and a literature professor

Richard Bower , Durham University and Simon John James , Durham University

Star Trek’s version of time travel is more realistic than most sci fi

Lloyd Strickland , Manchester Metropolitan University

Anthill 1: About time

Annabel Bligh , The Conversation and Gemma Ware , The Conversation

How to build a time machine

Steve Humble , Newcastle University

It’s Back to the Future Day today – so what are the next future predictions?

Michael Cowling , CQUniversity Australia ; Hamza Bendemra , Australian National University ; Justin Zobel , The University of Melbourne ; Philip Branch , Swinburne University of Technology ; Robert Merkel , Monash University ; Thas Ampalavanapillai Nirmalathas , The University of Melbourne , and Toby Walsh , Data61

Related Topics

- Albert Einstein

- Astrophysics

- Curious Kids

- Curious Kids US

- General Relativity

- Space travel

- Stephen Hawking

Top contributors

Associate Professor, Philosophy of Science, The University of Melbourne

Senior Lecturer in Philosophy, The University of Edinburgh

Professor of Physics, University of Rhode Island

Professor, University of Sydney

Honorary Research Associate, Centre for Time

Associate Professor in Telecommunications Engineering, Swinburne University of Technology

Emeritus Fellow, Trinity College, University of Cambridge

Former Academic Research Fellow, Khalifa University

Associate Professor, Film Studies, University of Sydney

Associate Professor – Information & Communication Technology (ICT), CQUniversity Australia

Lecturer in Software Engineering, Monash University

Professor in Physics, Durham University

Pro Vice-Chancellor, Graduate & International Research, The University of Melbourne

Professor of Philosophy and Intellectual History, Manchester Metropolitan University

Professor of Electrical and Electronic Engineering and Deputy Dean Research at Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, The University of Melbourne

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

October 21, 1999

According to current physical theory, is it possible for a human being to travel through time?

As several respondents noted, we constantly travel through time--just forward, and all at the same rate. But seriously, time travel is more than mere fantasy, as noted by Gary T. Horowitz, a professor of physics at the University of California at Santa Barbara:

"Perhaps surprisingly, this turns out to be a subtle question. It is not obviously ruled out by our current laws of nature. Recent investigations into this question have provided some evidence that the answer is no, but it has not yet been proven to be impossible."

Even the slight possibility of time travel exerts such fascination that many physicists continue to study not only whether it may be possible but also how one might do it.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

One of the leading researchers in this area is William A. Hiscock, a professor of physics at Montana State University. Here are his thoughts on the matter:

"Is it possible to travel through time? To answer this question, we must be a bit more specific about what we mean by traveling through time. Discounting the everyday progression of time, the question can be divided into two parts: Is it possible, within a short time (less than a human life span), to travel into the distant future? And is it possible to travel into the past?

"Our current understanding of fundamental physics tells us that the answer to the first question is a definite yes, and to the second, maybe.

"The mechanism for traveling into the distant future is to use the time-dilation effect of Special Relativity, which states that a moving clock appears to tick more slowly the closer it approaches the speed of light. This effect, which has been overwhelmingly supported by experimental tests, applies to all types of clocks, including biological aging.

"If one were to depart from the earth in a spaceship that could accelerate continuously at a comfortable one g (an acceleration that would produce a force equal to the gravity at the earth's surface), one would begin to approach the speed of light relative to the earth within about a year. As the ship continued to accelerate, it would come ever closer to the speed of light, and its clocks would appear to run at an ever slower rate relative to the earth. Under such circumstances, a round trip to the center of our galaxy and back to the earth--a distance of some 60,000 light-years--could be completed in only a little more than 40 years of ship time. Upon arriving back at the earth, the astronaut would be only 40 years older, while 60,000 years would have passed on the earth. (Note that there is no 'twin paradox,' because it is unambiguous that the space traveler has felt the constant acceleration for 40 years, while a hypothetical twin left behind on a spaceship circling the earth has not.)

"Such a trip would pose formidable engineering problems: the amount of energy required, even assuming a perfect conversion of mass into energy, is greater than a planetary mass. But nothing in the known laws of physics would prevent such a trip from occurring.

"Time travel into the past, which is what people usually mean by time travel, is a much more uncertain proposition. There are many solutions to Einstein's equations of General Relativity that allow a person to follow a timeline that would result in her (or him) encountering herself--or her grandmother--at an earlier time. The problem is deciding whether these solutions represent situations that could occur in the real universe, or whether they are mere mathematical oddities incompatible with known physics. No experiment or observation has ever indicated that time travel is occurring in our universe. Much work has been done by theoretical physicists in the past decade to try to determine whether, in a universe that is initially without time travel, one can build a time machine--in other words, if it is possible to manipulate matter and the geometry of space-time in such a way as to create new paths that circle back in time.

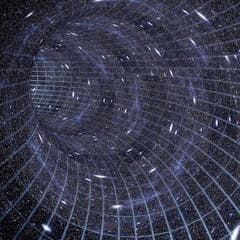

"How could one build a time machine? The simplest way currently being discussed is to take a wormhole (a tunnel connecting spatially separated regions of space-time) and give one mouth of the wormhole a substantial velocity with respect to the other. Passage through the wormhole would then allow travel to the past.

"Easily said--but where does one obtain a wormhole? Although the theoretical properties of wormholes have been extensively studied over the past decade, little is known about how to form a macroscopic wormhole, large enough for a human or a spaceship to pass through. Some speculative theories of quantum gravity tell us that space-time has a complicated, foamlike structure of wormholes on the smallest scales--10^-33 centimeter, or a billion billion times smaller than an electron. Some physicists believe it may be possible to grab one of these truly microscopic wormholes and enlarge it to usable size, but at present these ideas are all very hypothetical.

"Even if we had a wormhole, would nature allow us to convert it into a time machine? Stephen Hawking has formulated a "Chronology Protection Conjecture," which states that the laws of nature prevent the creation of a time machine. At the moment, however, this is just a conjecture, not proven.

"Theoretical physicists have studied various aspects of physics to determine whether this law or that might protect chronology and forbid the building of a time machine. In all the searching, however, only one bit of physics has been found that might prohibit using a wormhole to travel through time. In 1982, Deborah A. Konkowski of the U.S. Naval Academy and I showed that the energy in the vacuum state of a massless quantized field (such as the photon) would grow without bound as a time machine is being turned on, effectively preventing it from being used. Later studies by Hawking and Kip S. Thorne of Caltech have shown that it is unclear whether the growing energy would change the geometry of space-time rapidly enough to stop the operation of the time machine. Recent work by Tsunefumi Tanaka of Montana State University and myself, along with independent research by David Boulware of the University of Washington, has shown that the energy in the vacuum state of a field having mass (such as the electron) does not grow to unbounded levels; this finding indicates there may be a way to engineer the particle physics to allow a time machine to work.

"Perhaps the biggest surprise of the work of the past decade is that it is not obvious that the laws of physics forbid time travel. It is increasingly clear that the question may not be settled until scientists develop an adequate theory of quantum gravity."

John L. Friedman of the physics department at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee has also given this subject a great deal of consideration:

"Special relativity implies that people or clocks at rest (or not accelerating) age more quickly than partners traveling on round-trips in which one changes direction to return to one's partner. In the world's particle accelerators, this prediction is tested daily: Particles traveling in circles at nearly the speed of light decay more slowly than those at rest, and the decay time agrees with theory to the high precision of the measurements.

"Within the framework of Special Relativity, the fact that particles cannot move faster than light prevents one from returning after a high-speed trip to a time earlier than the time of departure. Once gravity is included, however, spacetime is curved, so there are solutions to the equations of General Relativity in which particles can travel in paths that take them back to earlier times. Other features of the geometries that solve the equations of General Relativity include gravitational lenses, gravitational waves and black holes; the dramatic explosion of discoveries in radio and X-ray astronomy during the past two decades has led to the observation of gravitational lenses and gravitational waves, as well as to compelling evidence for giant black holes in the centers of galaxies and stellar-sized black holes that arise from the collapse of dying stars. But there do not appear to be regions of spacetime that allow time travel, raising the fundamental question of what forbids them--or if they really are forbidden.

"A recent surprise is that one can circumvent the 'grandfather paradox,' the idea that it is logically inconsistent for particle paths to loop back to earlier times, because, for example, a granddaughter could go back in time to do away with her grandfather. For several simple physical systems, solutions to the equations of physics exist for any starting condition. In these model systems, something always intervenes to prevent inconsistency analogous to murdering one's grandfather.

"Then why do there seem to be no time machines? Two different answers are consistent with our knowledge. The first is simply that the classical theory has a much broader set of solutions than the correct theory of quantum gravity. It is not implausible that causal structure enters in a fundamental way in quantum gravity and that classical spacetimes with time loops are spurious--in other words, that they do not approximate any states of the complete theory. A second possible answer is provided by recent results that go by the name chronology protection: One supposes that quantum gravity allows microscopic structures that violate causality, and one shows that the character of macroscopic matter forbids the existence of regions with macroscopically large time loops. To create a time machine would require negative energy, and quantum mechanics appears to allow only extremely small regions of negative energy. And the forces needed to create an ordinary-sized region with time loops appear to be extremely large.

"To summarize: It is very likely that the laws of physics rule out macroscopic time machines, but possible that spacetime is filled with microscopic time loops.

- Search Menu

Time Travel: Probability and Impossibility

Reader in Philosophy

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

There are various arguments for the metaphysical impossibility of time travel, e.g. it’s impossible because objects could then be in two places at once, or it’s impossible because some objects could bring about their own existence. This book argues that no such argument is sound and that time travel is metaphysically possible. The main focus is on the Grandfather Paradox: if someone could go back in time, they could (impossibly!) kill their own grandfather before he met their grandmother, thus time travel is impossible. This book argues that, in such a case, the time traveller would have the ability to do the impossible (so they could kill their grandfather) even though those impossibilities will never come about (so they won’t kill their grandfather). The remainder of the book explores the ramifications of this view, discussing issues in probability and decision theory. It ends by laying out the dangers of time travel and why, even though no time machines currently exist, we should pay extra special care to ensure that nothing, no matter how small or microscopic, ever travels in time.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Discussions of the nature of time, and of various issues related to time, have always featured prominently in philosophy, but they have been especially important since the beginning of the twentieth century. This article contains a brief overview of some of the main topics in the philosophy of time—(1) fatalism; (2) reductionism and Platonism with respect to time; (3) the topology of time; (4) McTaggart’s argument; (5) the A-theory and the B-theory; (6) presentism, eternalism, and the growing block theory; (7) the 3D/4D debate about persistence; (8) the dynamic and the static theory; (9) the moving spotlight theory; (10) time travel; (11) time and physics and (12) time and rationality. We include some suggestions for further reading on each topic and a bibliography.

Note: This entry does not discuss the consciousness, perception, experience, or phenomenology of time. A historical overview and general presentation of the various views is available in the entry on temporal consciousness . Further coverage can be found in the SEP entry on the experience and perception of time . For those interested specifically in phenomenological views, see the entries on Husserl (Section 6), and Heidegger (Section 2: Being and Time).

1. Fatalism

2. reductionism and platonism with respect to time, 3. the topology of time, 4. mctaggart’s argument, 5. the a-theory and the b-theory, 6. presentism, eternalism, and the growing block theory, 7. three-dimensionalism and four-dimensionalism, 8. the dynamic and the static theory, 9. the moving spotlight theory, 10. time travel, 11. time and physics, 12. time and rationality, other internet resources, related entries.

Many logical questions about time historically arose from questions about freedom and determinism—in particular worries about fatalism. Fatalism can be understood as the doctrine that whatever will happen in the future is already unavoidable (where to say that an event is unavoidable is to say that no agent is able to prevent it from occurring). Here is a typical argument for fatalism:

The conclusion appears shocking. Future moral catastrophes are unavoidable. Every weighty decision that now feels up to you is already determined.

The argument for fatalism makes some significant metaphysical assumptions that raise more general questions about logic, time, and agency.

For example, Premise (1) assumes that propositions describing the future do not come into or go out of existence. It assumes that there are propositions now that can accurately represent every future way things might go. This is a non-trivial logical assumption. You might, for instance, think that different times becoming present and actual (like perhaps possible worlds) have different associated sets of propositions that become present and actual.

Premise (2) appears to be a fundamental principle of semantics, sometimes referred to as the Principle of Bivalence.

The rationale for premise (4) is that it appears no one is able to make a true prediction turn out false. (4) assumes that one and the same proposition does not change its truth value over time. The shockingness of the conclusion also depends on identifying meaningful agency with the capacity to make propositions come out true or false.

A proper discussion of fatalism would include a lengthy consideration of premises (1) and (4), which make important assumptions about the nature of propositional content and the nature of agency. That would take us beyond the scope of this article. For our purposes, it is important to note that many writers have been motivated by this kind of fatalist argument to deny (2), the Principle of Bivalence. According to this line, there are many propositions—namely, propositions about events that are both in the future and contingent—that are neither true nor false right now. Consider the proposition that you will have lunch tomorrow. Perhaps that proposition either has no truth value right now, or else has a third truth value: indeterminate. When the relevant time comes, and you either have lunch or don’t, then the proposition will come to be either true or false, and from then on that proposition will forever retain that determinate truth value.

This strategy for rejecting fatalism is sometimes referred to as the “Open Future” response. The Open Future response presupposes that a proposition can have a truth value, but only temporarily—truth values for complete propositions can change as time passes and the world itself changes. This raises further questions about the correct way to link up propositions, temporal passage and truth values. For example, which of the following formulas expresses a genuine proposition about the present?

Tensed Proposition: “Sullivan is eating a burrito”.

Tenseless Proposition: “Sullivan eats a burrito at <insert present time stamp>”.

The tensed proposition will no longer be true when Sullivan finishes her lunch. So it has, at best, a temporary truth value. The tenseless proposition expresses something like “Sullivan eats a burrito at 3pm on July 20th 2019”. That proposition is always true.

Some philosophers argue that only the latter, eternally true kind of proposition could make sense of how we use propositions to reason over time. We need propositions to have stable truth values if we are to use them as the contents of thoughts and communication. Other philosophers—particularly those who believe that reality itself changes over time—think that tensed propositions are needed to accurately reason about the world. We’ll return to these issues in Section 4 and Section 5 .

Suggestions for Further Reading: Aristotle, De Interpretatione , Ch. 9; Barnes and Cameron 2009; Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy , Book V; Crisp 2007; Evans 1985; Lewis 1986; Markosian 1995; McCall 1994; Miller 2005; Richard 1981; Sullivan 2014; Taylor 1992; Torre 2011; Van Inwagen 1983.

What if one day things everywhere ground to a halt? What if birds froze in mid-flight, people froze in mid-sentence, and planets and subatomic particles alike froze in mid-orbit? What if all change, throughout the entire universe, completely ceased for a period of, say, one year? Is such a thing possible?

If the answer to this last question is “yes”—if it is possible for there to be time without change—then time is in some important sense independent of the events within time. Other ways of investigating whether time is independent of the events within time include asking whether all of the physical processes that happen in time could happen at a faster or slower rate, and asking whether all events could have happened slightly earlier or later in time. After all, if every physical process could suddenly happen twice as fast, or if every event could take place slightly earlier or later in time, then it follows that in some important sense time can remain the same even if the way that events are distributed in time changes wholesale.

Aristotle and Leibniz, among others, have argued that time is not independent of the events that occur in time. This view is typically called either “reductionism with respect to time” or “relationism with respect to time”, since according to this view, all talk that appears to be about time can somehow be reduced to talk about temporal relations among things and events. The opposing view, normally referred to either as “Platonism with respect to time” or “substantivalism with respect to time” or “absolutism with respect to time”, has been defended by Plato, Newton, and others. On this view, time is like an empty container into which things and events may be placed; but it is a container that is independent of what (if anything) is placed in it.

Another way to present this distinction is to say that those like Plato and Newton who think that time is independent of the events that occur in time believe in “absolute time”. Those like Aristotle and Leibniz, who think that time is not independent of the events that occur in time, deny the existence of absolute time, though they still endorse “relative time”, where relative time is nothing over and above the temporal relations between events.

These views about time are closely connected to views about space and about motion. Most obviously, these views about time have straightforward spatial analogues—one may be a substantivalist about space (and thus endorse the existence of absolute space in addition to spatial relations between things), or one may be a relationist about space (and thus deny the existence of absolute space). Substantivalism and relationism about time have traditionally been taken to stand or fall with their spatial counterparts. In addition, the choice between substantivalism and relationism about space and time has consequences for your theory of motion. If you are a relationist about space and time then you must also be a relationist about motion: all motion is motion relative to something. If you are a substantivalist about space and time, you will endorse, in addition to relative motion, the notion of absolute motion, where absolute motion is motion relative to absolute space and time. If you are a substantivalist, in addition to facts about whether and how fast a train car is moving relative to the track, whether and how fast it is moving relative to the cars, and so on, there will also be a fact about whether and how fast the train car is really moving—whether and how fast it is moving relative to absolute space and time.

Why would someone endorse the existence of absolute time? One reason is that the empty container metaphor has a lot of intuitive appeal. Another reason is that some philosophers have thought that there must be such a thing as absolute motion—as opposed to merely relative motion—in order to explain certain physical phenomena, like the forces felt during acceleration. Newton had an especially famous argument along these lines involving a spinning bucket of water—the entry on Newton’s views on space, time , and motion has a careful discussion of this argument.

Why would someone deny the existence of absolute time? Some relationists have put forward arguments that are supposed to show that absolute space and time are philosophically problematic in some important way. Perhaps most famously, Leibniz argued that the existence of absolute space or time would lead to violations of the principle of sufficient reason and violations of the identity of indiscernibles.

In order to see why, consider two ways of describing the way things could be. On the one hand, everything is as it actually is. On the other, every event happens one second later than it actually does, but is otherwise exactly the same. If there is such a thing as absolute time then these two descriptions would pick out distinct possible worlds. But this, Leibniz claimed, would violate the principle of sufficient reason. For given that the actual world and the one-second-late world are exactly the same except for where things are located in absolute time, there could not (at least according to Leibniz) be any reason why one exists rather than the other. Moreover, Leibniz claimed, the actual world and the one-second-late world are indistinguishable; so if they were in fact distinct possible worlds, that would violate the principle that if two things are indistinguishable, then they are identical.

Leibniz’s arguments are examples of arguments that attempt to identify something philosophically problematic with absolute time and space. Perhaps more generally, many philosophers have been moved by the idea that even if absolute time and space are not problematic in a way that makes them unacceptable, they are still the kinds of things that we should do without if we can. This kind of attitude can be motivated by a straightforward kind of parsimony—we should always make do with the fewest types of entities possible. Or it can be motivated by a more specific worry about the nature of absolute space and time. You might, for instance, be especially loath to admit unobservable entities into your ontology—you are willing to admit them if you must, but you would rather eliminate them wherever possible. As absolute space and time are unobservable, someone who endorses this attitude will be inclined to think there are no such things.

Suggestions for Further Reading : Alexander 1956; Ariew 2000; Arntzenius 2012; Coope 2001; Mitchell 1993; Newton, Philosophical Writings ; Newton-Smith 1980; Shoemaker 1969.

It’s natural to think that time can be represented by a line. But a line has a shape. What shape should we give to the line that represents time? This is a question about the topology, or structure, of time.

One natural way to answer our question is to say that time should be represented by a single, straight, non-branching, continuous line that extends without end in each of its two directions. This is the “standard topology” for time. But for each of the features attributed to time in the standard topology, two interesting questions arise: (a) does time in fact have that feature? and (b) if time does have the feature in question, is this a necessary or a contingent fact about time?

Questions about the topology of time appear to be closely connected to the issue of Platonism versus relationism with respect to time. For if relationism is true, then it seems likely that time’s topological features will depend on contingent facts about the relations among things and events in the world, whereas if Platonism is true, so that time exists independently of whatever is in time, then time will presumably have its topological properties as a matter of necessity. But even if we assume that Platonism is true, it’s not clear exactly what topological properties should be attributed to time.

Consider the question of whether time should be represented by a line without a beginning (so a line, rather than a line segment). Aristotle has argued (roughly) that time cannot have a beginning on the grounds that in order for time to have a beginning, there must be a first moment of time, but that in order to count as a moment of time, that allegedly first moment would have to come between an earlier period of time and a later period of time, which is inconsistent with its being the first moment of time. (Aristotle argues in the same way that time cannot have an end.)

Aristotle’s argument may or may not be a good one, but even if it is unsound, many people will feel, purely on intuitive grounds, that the idea of time having a beginning (or an end) just does not make sense. And here we have an excellent illustration of what is at stake in the controversy over whether time has its topological properties as a contingent matter or as a matter of necessity. For suppose we come to have excellent evidence that the universe itself had a beginning in time. (This seems like the kind of thing that could be supported by empirical evidence in cosmology.) This would still leave open the question of whether the beginning of the universe occurred after an infinitely long period of “empty” time, or, instead, coincided with the beginning of time itself. There are interesting and plausible arguments for each of these positions.

It is also worth asking whether time must be represented by a single line. Perhaps we should take seriously the possibility of time’s consisting of multiple time streams, each one of which is isolated from each other, so that every moment of time stands in temporal relations to other moments in its own time stream, but does not bear any temporal relations to any moment from another time stream. Likewise we can ask whether time could correspond to a branching line (perhaps to allow for the possibility of time travel or to model an open future), or to a closed loop, or to a discontinuous line. And we can also wonder whether one of the two directions of time is in some way privileged, in a way that makes time itself asymmetrical. (We say more about this last option in particular in the section on time and physics.)

Suggestions for Further Reading: (1) On the beginning and end of time: Aristotle, Physics , Bk. VIII; Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason (especially pp. 75ff); Newton-Smith 1980, Ch. V. (2) On the linearity of time: Newton-Smith 1980, Ch. III; Swinburne 1966, 1968. (3) On the direction of time: Price 1994, 1996; Savitt 1995; and Sklar 1974. (4) On all of these topics: Newton-Smith 1980.

In a famous paper published in 1908, J.M.E. McTaggart argued that there is in fact no such thing as time, and that the appearance of a temporal order to the world is a mere appearance. Other philosophers before and since (including, especially, F.H. Bradley) have argued for the same conclusion. We will focus here only on McTaggart’s argument against the reality of time, which has been by far the most influential.

McTaggart begins his argument by distinguishing two ways in which positions in time can be ordered. First, he says, positions in time can be ordered according to their possession of properties like being two days future, being one day future, being present, being one day past, etc. These properties are often referred to now as “ A properties” because McTaggart calls the series of times ordered by these properties “the A series”. But he says that positions in time can also be ordered by two-place relations like two days earlier than, one day earlier than, simultaneous with, etc. These relations are now often called “ B relations” because McTaggart calls the series of times ordered by these relations “the B series”.

McTaggart argues that the B series alone does not constitute a proper time series; the A series is essential to time. His reason for this is that he assumes change is essential to time, and the B series without the A series does not involve genuine change (since B series positions are forever “fixed”, whereas A series positions are constantly changing).

McTaggart also argues that the A series is inherently contradictory. For, he says, the different A properties are incompatible with one another. No time can be both future and past, for example. Nevertheless, he insists, each time in the A series must possess all of the different A properties, since a time that is future will be present and then will be past. McTaggart concludes that, since neither the A-series nor the B-series can order the time series, time is unreal.

One response to this argument that McTaggart anticipates involves claiming that it’s not true of any time, t , that t is both future and past. Rather, the objection goes, we must say that it was future at some moment of past time and will be past at some moment of future time. But this objection fails, according to McTaggart, because the additional times that are invoked in order to explain t ’s possession of the incompatible A properties must themselves possess all of the same A properties (as must any further times invoked on account of these additional times, and so on ad infinitum ). Thus, according to McTaggart, we never resolve the original contradiction inherent in the A series, but, instead, merely generate an infinite regress of more and more contradictions.

McTaggart’s argument has had staying power because it organizes crucial debates about the metaphysics of temporal passage, because it hints at how those debates connect to further debates about where evidence for the time series and the nature of change come from, and because the difference between A-theoretic and B-theoretic approaches to the debate has continued in the intervening century.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Bradley 1893; Dyke 2002; McTaggart 1908; Mellor 1998; Prior 1967, 1968.

In Section 1 , we introduced the distinction between a tensed proposition and a tenseless proposition. Tensed propositions can fully and accurately describe the world, but nevertheless change truth value over time. Tenseless propositions, on the other hand, are always true or always false—they reference a particular time in the proposition and never change. Propositions represent ways reality could be. So, which view of propositions we adopt depends on what we think it means for reality itself to undergo change.

In section 4 , we discussed McTaggart’s distinction between time conceived of as a B-series (events ordered by which come before and which come after) and time conceived of as an A-series (events ordered by which are present, which are past, and which are future). Though not particularly creative as names, the A/B distinction has stuck around as a way of classifying theories of change.

B-theorists think all change can be described in before-after terms. They typically portray spacetime as a spread-out manifold with events occurring at different locations in the manifold (often assuming a substantivalist picture). Living in a world of change means living in a world with variation in this manifold. To say that a certain autumn leaf changed color is just to say that the leaf is green in an earlier location of the manifold and red in a later location. The locations, in these cases, are specific times in the manifold. And all of the metaphysically important facts about change can be captured by tenseless propositions like “The leaf is red at October 7, 2019”. “The leaf is not red at September 7, 2019”.

A-theorists, on the other hand, believe that at least some important forms of change require classifying events as past, present or future. And accurately describing this kind of change requires some tensed propositions—there is a way reality is (now, presently) which is complete but was different in the past and also will be different in the future. These tensed propositions also explain why we tend to attribute significance to the past-present-future distinction. For example, you might think the A-theorist is in a better position to explain why we care whether a horrible event is already in the past versus still in the future. Some A-theorists will argue that we aren’t concerned with location—we care that the event is over with in reality.

Note, also, there is a significant range of views within the A-theory camp about whether there is a spacetime manifold (Moving Spotlighters think there is), or whether only present events are real (the presentist view), or whether only present and past events are real (the Growing Block view). We say more about all of these views below. A-theorists also debate whether objects themselves undergo A-theoretic change or whether it is only entire regions of spacetime that change this way.

A-theorists and B-theorists appeal to different sources of evidence for their different views of passage. A-theorists typically emphasize how psychologically we seem to perceive a world of robust passage or “flow” of time. In physics, the laws of thermodynamics seem to imply a strong past-to-future direction to time. And quantum mechanics seems to identify an important sense of simultaneity, which could be identified with presentness (see section 11 below). Finally many commonsense ways of thinking of change seem to rely on A-theory descriptions of passage. For instance, they will use the fact that we care so much about whether bad events are past as evidence that there are ineliminable tensed propositions and those propositions represent ineliminable A-properties.

B-theorists typically emphasize how special relativity eliminates the past/present/future distinction from physical models of space and time. Thus what seems like an awkward way to express facts about time in ordinary English is actually much closer to the way we express facts about time in physics. Moreover, thinking of change in tenseless terms makes it easier to describe in a logically consistent way how objects survive change—objects have properties only relative to particular times, so there is no worry about attributing absolutely inconsistent properties to anything. We’ll consider some of these arguments in more detail in the remaining sections of this entry, as we consider more specific variations on A-theories and B-theories of time.

Suggestions for Further Reading: For general discussion of The A theory and The B theory: Emery 2017; Le Poidevin 1998; Le Poidevin and McBeath 1993; Markosian 1993; Maudlin 2007 (especially Chapter 4); Mellor 1998; Paul 2010; Prior 1959 [1976], 1962 [1968], 1967, 1968, 1970, 1996; Sider 2001; Skow 2009; Smart 1963, 1949; Smith 1993; Sullivan 2012a; Williams 1951; Zimmerman 2005; Zwart 1976.

A further question that you might ask about time is an ontological question. Does whether something is past, present, or future make a difference to whether it exists? And how do these ontological theses connect to debates about the A-theory and the B-theory?

According to presentism, only present objects exist. More precisely, presentism is the view that, necessarily, it is always true that only present objects exist. Even more precisely, no objects exist in time without being present (abstract objects might exist outside of time). (Note that some writers have used the name differently, and unless otherwise indicated, what is meant here by “present” is temporally present, as opposed to spatially present.) According to presentism, if we were to make an accurate list of all the things that exist—i.e., a list of all the things that our most unrestricted quantifiers range over—there would be not a single merely past or merely future object on the list. Thus, you and the Taj Mahal would be on the list, but neither Socrates nor any future Martian outposts would be included. (Assuming, that is, both (i) that each person is identical to his or her body, and (ii) that Socrates’s body ceased to be present—thereby going out of existence, according to presentism—shortly after he died. Those who reject the first of these assumptions should simply replace the examples in this article involving allegedly non-present people with appropriate examples involving the non-present bodies of those people.) And it is not just Socrates and future Martian outposts, either—the same goes for any other putative object that lacks the property of being present. No such objects exist, according to presentism.

There are different ways to oppose presentism—that is, to defend the view that at least some non-present objects exist. One version of non-presentism is eternalism, which says that objects from both the past and the future exist. According to eternalism, non-present objects like Socrates and future Martian outposts exist now, even though they are not currently present. We may not be able to see them at the moment, on this view, and they may not be in the same space-time vicinity that we find ourselves in right now, but they should nevertheless be on the list of all existing things.

It might be objected that there is something odd about attributing to a non-presentist the claim that Socrates exists now, since there is a sense in which that claim is clearly false. In order to forestall this objection, let us distinguish between two senses of “ x exists now”. In one sense, which we can call the temporal location sense, this expression is synonymous with “ x is present”. The non-presentist will admit that, in the temporal location sense of “ x exists now”, it is true that no non-present objects exist now. But in the other sense of “ x exists now”, which we can call the ontological sense, to say that “ x exists now” is just to say that x is now in the domain of our most unrestricted quantifiers. Using the ontological sense of “exists”, we can talk about something existing in a perfectly general sense, without presupposing anything about its temporal location. When we attribute to non-presentists the claim that non-present objects like Socrates exist right now, we commit non-presentists only to the claim that these non-present objects exist now in the ontological sense (the one involving the most unrestricted quantifiers).

According to the eternalist, temporal location does not affect ontology. But according to a somewhat less popular version of non-presentism, temporal location does matter when it comes to ontology, because only objects that are either past or present exist. On this view, which is often called the growing block theory, the correct ontology is always increasing in size, as more and more things are added on to the leading “present” edge (temporally speaking). (Note, however, that the growing block theory does not involve any commitment to four-dimensionalism as discussed in section 7 . In this way, the name “growing block” is somewhat misleading and the view is probably better described as the growing universe theory.) Both presentism and the growing block theory are versions of the A-theory.

Despite the claim by some presentists that theirs is the commonsense view, it is pretty clear that there are some major problems facing presentism (and, to a lesser extent, the growing block theory; but in what follows we will focus on the problems facing presentism). One problem has to do with what appears to be perfectly meaningful talk about non-present objects, such as Socrates and the year 3000. If there really are no non-present objects, then it is hard to see what we are referring to when we use expressions such as “Socrates” and “the year 3000”.

Another problem for the presentist has to do with relations involving non-present objects. It is natural to say, for example, that Abraham Lincoln was taller than Napoleon Bonaparte, and that World War II was a cause of the end of The Depression. But how can we make sense of such talk, if there are no non-present objects to be the relata of those relations?

A third problem for the presentist has to do with the very plausible principle that for every truth, there is a truth-maker—something whose existence suffices for the truth of the proposition or statement. If you are a presentist, it is hard to see what the truth-makers could be for truths such as that there were dinosaurs and that there will be Martian outposts.

Finally, the presentist, in virtue of being an A-theorist, must deal with the arguments against the A-theory that were mentioned above, including especially the worry that the A-theory is incompatible with special relativity. We will discuss these physics-based objections below.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Adams 1986; Bourne 2006; Bigelow 1996; Emery 2020; Hinchliff 1996; Ingram 2016; Keller and Nelson 2001; Markosian 2004, 2013; McCall 1994; Rini and Cresswell 2012; Sider 1999, 2001; Sullivan 2012b; Tooley 1997; Zimmerman 1996, 1998.

In Section 4 and Section 5 we saw that there have been two main theories developed in response to McTaggart’s Argument: The A-theory and The B-theory. Then, in Section 6 we saw that there are two main ways of thinking about the relation between ontology and time: presentism and eternalism. (There was also a third way, The Growing Block Theory, which we will mainly set aside for the sake of simplicity in this section.) Two main ways of thinking about time emerge from these discussions. On the one hand, A-theorists and presentists think that our pre-theoretical idea of time as flowing or passing, and thus being very different from the dimensions of space, corresponds to something objective and real. B-theorists and eternalists, on the other hand, reject the idea of time’s passage and instead embrace the idea of time as being a dimension like space. There is another important way in which philosophers in the second camp (the B-theory/eternalist camp) think time is like space, and it has to do with how objects and events persist over time. The debate typically centers around the doctrine of “temporal parts”, which those in the B-theory/eternalist camp tend to accept while those in the A-theory/presentist camp tend to reject.

To get an intuitive idea of what temporal parts are supposed to be, think of a film strip depicting you as you walk across a room. It is made up of many frames, and each frame shows you at a moment of time. Now picture cutting the frames, and stacking them, one on top of another. Finally, imagine turning the stack sideways, so that the two-dimensional images of you are all right-side-up. Each image of you in one of these frames represents a temporal part of you, in a specific position, at a particular location in space, at a single moment of time. And what you are, on this way of thinking, is the fusion of all these temporal parts. You are a “spacetime worm” that curves through the four-dimensional manifold known as spacetime . Moreover, on this view, what it is to have a momentary property at a time is to have a temporal part at the time that has the property in question. So you are sitting right now in virtue of the fact that your current temporal part is sitting.

The doctrine of temporal parts that B-theorists and eternalists tend to like can be stated like this:

Four-Dimensionalism: Any physical object that is located at different times has a different temporal part for each moment at which it is located.

On this view you have a temporal part right now, which is a three-dimensional “time slice” of you. And you have a different temporal part at noon yesterday, but no temporal parts in the year 1900 (since you are not located at any time in 1900). Also on this view, the physical object that is you is a fusion of all of your many temporal parts. (Note: there is a variation on the standard four-dimensional view, which is sometimes called “the worm view”. The variation, known as “the stage view”, holds that names and personal pronouns normally refer, not to entire fusions of temporal parts but, rather, to the individual person-stages, each of which is located at just an instant of time, and each of which counts as a person, rather than a mere part of a person).

The opposing view is three-dimensionalism, which is just the denial of the claim that temporally extended physical objects must have temporal parts. Here is a formulation of the view:

Three-Dimensionalism: Any physical object that is located at different times is wholly present at each moment at which it is located.

According to three-dimensionalism, the thing that was doing whatever you were doing at noon yesterday was you. It was you who was doing that, and now you are doing something different (namely, reading this sentence). So the relation between “you then” and “you now” is identity . According to four-dimensionalism, on the other hand, the thing that was doing whatever you were doing at noon yesterday was an earlier temporal part of the thing that is you, and the thing that is doing what you are doing now is the present temporal part of you. The relation between “you then” and “you now” is the temporal counterpart relation. (This is similar to the relation between your left hand and your right hand, which is the spatial counterpart relation. Your two hands are distinct parts of a bigger thing that contains them both.)

David Lewis, one of the main proponents of four-dimensionalism, suggests that the principal reason to accept the view is to solve what he calls “the problem of temporary intrinsics”. How can a single thing—Lewis, for example—have different intrinsic properties—like being straight, while he is standing, and then being bent, while seated—at different times? Not by standing in different relations—the being straight at and being bent at relations—to different times, he argues. (Since, he says, being straight and being bent are genuine properties rather than disguised relations.) And not in virtue of there being only one reality—such as the time when Lewis is bent—so that reality consists of Lewis, and every other thing, being the way it is now and not any other way. (For Lewis points out that we all believe we have a past and a future, in addition to a present.) So Lewis suggests that the best answer to the question about how a single thing can have different intrinsic properties at different times is that such an object has different temporal parts which themselves have the different intrinsic properties.

There is, however, a natural three-dimensionalist response to this argument. It involves appealing to a certain way of thinking about time, truth, and propositions that we touched on briefly in Section 1 , namely, the idea that propositions are in some way “tensed” as opposed to “tenseless”. Here is a way to formulate the relevant semantic thesis:

The Tensed Conception of Semantics

- Propositions have truth values at times rather than simpliciter and can, in principle, change their truth values over time.

- We cannot eliminate verbal tenses like is , was , and will be from an ideal language.

On this view, a sentence like “Sullivan is eating a burrito” expresses a proposition that used to be true, but is false now.

The alternative to the tensed conception of semantics is the tenseless conception of semantics . On the latter view, an utterance of a sentence like “Sullivan is eating a burrito” expresses a proposition about a B-relation between events—it says that Sullivan’s eating a burrito is simultaneous with the utterance itself (or perhaps with the time of the utterance). Here is a way of stating this view:

The Tenseless Conception of Semantics

- Propositions have truth values simpliciter rather than at times, and so cannot change their truth values over time.

- We can in principle eliminate verbal tenses like is , was , and will be from an ideal language.

Consideration of Lewis’s argument from temporary intrinsics has shown that a three-dimensionalist should probably endorse the tensed conception of semantics, in order to account for changing truths about the world and its objects. And once we have seen this, it also becomes clear that A-theorists, presentists, and proponents of the growing block theory all have similar reasons for adopting the tensed conception of semantics. For the A-theorist is committed to there being changing truths about which times and events are future, which are present, and which are past; and presentists and growing block theorists are both committed to there being changing truths about what exists.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Hawley 2004 [2020]; Lewis 1986; Sider 2001; Thomson 1983; van Inwagen 1990

Many of the above considerations—especially those about McTaggart’s Argument; the A-theory and the B-theory; presentism, eternalism, and the growing block theory; and the dispute between three-dimensionalism and four-dimensionalism—suggest that there are, generally speaking, two very distinct ways of thinking about the nature of time. The first is the Static Theory of Time, according to which time is like space, and there is no such thing as the passage of time; and the second is the Dynamic Theory of Time, according to which time is very different from space, and the passage of time is a real phenomenon. These two ways of thinking about time are not the only such ways, but they correspond to the two most popular combinations of views about time to be found in the literature, which are arguably the most natural combinations of views on these issues. In this section we will spell out these two popular combinations, mainly as a way to synthesize much of the preceding material, and also to allow the reader to appreciate in a big-picture way how the different disputes about the nature of time are normally taken to be interrelated.

The guiding thought behind the Static Theory of Time is that time is like space. Here are six ways in which this thought is typically spelled out. (Note: The particular combination of these six theses is a natural and popular combination of related claims. But it is not inevitable. It is also possible to mix and match from among the tenets of the Static Theory and its rival, the Dynamic Theory.)

The Static Theory of Time

- The universe is spread out in four similar dimensions, which together make up a unified, four-dimensional manifold, appropriately called spacetime .

- Any physical object that is located at different times has a different temporal part for each moment at which it is located.

- There are no genuine and irreducible A-properties; all talk that appears to be about A-properties can be correctly analyzed in terms of B-relations. Likewise, the temporal facts about the world include facts about B-relations, but they do not include any facts about A-properties.

- The correct ontology does not change over time, and it always includes objects from every region of spacetime.

- Propositions have truth values simpliciter rather than at times, and so cannot change their truth values over time. Also, we can in principle eliminate verbal tenses like is , was , and will be from an ideal language.

- There is no dynamic aspect to time; time does not pass.

Static Theorists of course admit that time seems special to us, and that it seems to pass. But they insist that this is just a feature of consciousness—of how we perceive the world—and not a feature of reality that is independent of us.

The second of the main ways of thinking about time is the Dynamic Theory of Time. The guiding thought behind this way of thinking is that time is very different from space. Here are six ways in which this thought is typically spelled out. (Note: The particular combination of these six theses is a natural and popular combination of related claims. But, like the Static Theory, it is not inevitable. It is also possible to mix and match from among the tenets of the Dynamic Theory and the Static Theory.)

The Dynamic Theory of Time

- The universe is spread out in the three dimensions of physical space, and time, like modality, is a completely different kind of dimension from the spatial dimensions.

- Any physical object that is located at different times is wholly present at each moment at which it is located.

- There are genuine and irreducible A-properties, which cannot be correctly analyzed in terms of B-relations. The temporal facts about the world include ever-changing facts involving A-properties, including facts about which times are past, which time is present, and which times are future.

- The correct ontology changes over time, and it is always true that only present objects exist.

- Propositions have truth values at times rather than simpliciter and can, in principle, change their truth values over time. Also, we cannot eliminate verbal tenses like is , was , and will be from an ideal language.

- The passage of time is a real and mind-independent phenomenon.

Opponents of the Dynamic Theory (and sometimes proponents as well) like to characterize the theory using the metaphor of a moving spotlight that slides along the temporal dimension, brightly illuminating just one moment of time, the present, while the future is a foggy region of potential and the past is a shadowy realm of what has been. The moving spotlight is an intuitively appealing way to capture the central idea behind the Dynamic Theory, but in the end, it is just a metaphor. What the metaphor represents is the idea that A-properties like being future , being present , and being past are objective and metaphysically significant properties of times, events, and things. Also, the metaphor of the moving spotlight represents the fact that, according to the Dynamic Theory, each time undergoes a somewhat peculiar but inexorable process, sometimes called temporal becoming . It goes from being in the distant future to the near future, has a brief moment of glory in the present, and then recedes forever further and further into the past.

Despite its being intuitively appealing (especially for Static Theorists, who see it as a caricature of the Dynamic Theory), the moving spotlight metaphor has a major drawback, according to some proponents of the Dynamic Theory: it encourages us to think of time as a fourth dimension, akin to the dimensions of space. For many proponents of the Dynamic Theory, this way of thinking—“spatializing time”—is a mistake. Instead, we should take seriously the ways that time seems completely different from the dimensions of space—for instance, time’s apparent directionality, and the distinctive ways that time governs experience.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Hawley 2001; Lewis 1986; Markosian 1993; Markosian 2004; Markosian (forthcoming); Moss 2012; Price 1977; Prior 1967; Prior 1968; Sider 2001; Smart 1949; Sullivan 2012a; Thomson 1983; and Williams 1951.

Above we mentioned that a metaphor sometimes used to characterize the Dynamic Theory is that of a moving spotlight that slides along the temporal dimension and that is such that only objects within the spotlight exist. A similar sort of metaphor can also be used to characterize the Moving Spotlight Theory, which is an interesting hybrid of the Static Theory and the Dynamic Theory. Like the Static Theory, the Moving Spotlight Theory incorporates the idea of spacetime as a unified manifold, with objects spread out along the temporal dimension in virtue of having different temporal parts at different times, and with past, present, and future parts of the manifold all equally real. But like the Dynamic Theory, it incorporates the thesis that A-properties are objective and irreducible properties, as well as the idea that time genuinely passes. The metaphor that characterizes the Moving Spotlight Theory is one on which there is a moving spotlight that slides along the temporal dimension and that is such that only things that are within the spotlight are present (but things that are outside the spotlight still exist).

Thus the Moving Spotlight Theory is an example of an eternalist A-theory that subscribes to the dynamic thesis. Unlike presentist or growing block theories, spotlighters deny that any objects come into or out of existence. Unlike the B-theories, however, spotlighters think that there is an important kind of change that cannot be described just as mere variation in a spacetime manifold. Spotlighters think instead that there is a spacetime manifold, but one particular region of the manifold is objectively distinguished—the present. And this distinction is only temporary—facts about which region of spacetime count as the present change over time. For example, right now a region of 2019 is distinguished as present. But in a year, a region of 2020 will enjoy this honor. The term “moving spotlight theory” was coined by C.D. Broad—himself a growing blocker—because he thought this view of time treated passage on the metaphor of a policeman’s “bull’s eye” scanning regions in sequence and focusing attention on their contents.

Just as there are different understandings of presentism and eternalism, there are different versions of the moving spotlight theory. Some versions think that even though the present is distinguished, there is still an important sense in which the past and future are concrete. Other versions (like Cameron 2015) treat the spotlight theory more like a variant of presentism—past and future objects still exist, but their intrinsic properties are radically unlike those of present objects. Fragmentalists (see Fine 2005) think that there is a spacetime manifold but that every point in the manifold has its own type of objective presentness, which defines a past and future relative to the point.

Why be a spotlighter? Advocates think it combines some of the best features of eternalism while still making sense of how we seem to perceive a world of substantive passage. It also inherits some of the counterintuitive consequences of eternalism (i.e., believing dinosaurs still exist) and the more complicated logic of the A-theories (i.e., it requires rules for reasoning about tensed propositions involving the spotlight).

Suggestions for Further Reading: Broad 1923; Cameron 2015; Fine 2005; Hawley 2004 [2020]; Lewis 1986 (especially Chapter 4.2); Sider 2001; Skow 2015; Thomson 1983; Van Inwagen 1990; Zimmerman 1998.

We are all familiar with time travel stories, and there are few among us who have not imagined traveling back in time to experience some particular period or meet some notable person from the past. But is time travel even possible?

One question that is relevant here is whether time travel is permitted by the prevailing laws of nature. This is presumably a matter of empirical science (or perhaps the correct philosophical interpretation of our best theories from the empirical sciences). But a further question, and one that falls squarely under the heading of philosophy, is whether time travel is permitted by the laws of logic and metaphysics. For it has been argued that various absurdities follow from the supposition that time travel is (logically and metaphysically) possible. Here is an example of such an argument:

Another argument that might be raised against the possibility of time travel depends on the claim that presentism is true. For if presentism is true, then neither past nor future objects exist. And in that case, it is hard to see how anyone could travel to the past or the future.

A third argument, against the possibility of time travel to the past, has to do with the claim that backward causation is impossible. For if there can be no backward causation, then it is not possible that, for example, your pushing the button in your time machine in 2020 can cause your appearance, seemingly out of nowhere, in, say, 1900. And yet it seems that any story about time travel to the past would have to include such backward causation, or else it would not really be a story about time travel.

Despite the existence of these and other arguments against the possibility of time travel, there may also be problems associated with the claim that time travel is not possible. For one thing, many scientists and philosophers believe that the actual laws of physics are in fact compatible with time travel. And for another thing, as we mentioned at the beginning of this section, we often think about time travel stories; but when we do so, those thoughts do not have the characteristic, glitchy feeling that is normally associated with considering an impossible story. To get a sense of the relevant glitchy feeling, consider this story: Once upon a time there was a young girl, and two plus two was equal to five . When you try to consider that literary gem, you mainly have a feeling that something has gone wrong (you immediately want to respond, “No, it wasn’t”), and the source of that feeling seems to be the metaphysical impossibility of the story being told. But nothing like this happens when you consider a story about time travel (especially if it is one of the logically consistent stories about time travel, such as the one depicted in the movie Los Cronocrímenes (Timecrimes) ). One task facing the philosopher who claims that time travel is impossible, then, is to explain the existence of a large number of well-known stories that appear to be specifically about time travel, and that do not cause any particular cognitive dissonance.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Bernstein 2015, 2017; Dyke 2005; Earman 1995; Markosian (forthcoming); Meiland 1974; Miller 2017; Sider 2001; Thorne 1994; Vihvelin 1996; Yourgrau 1999.

Our best physical theories have often had implications for the nature of time, and by and large, it is assumed that philosophers working on time need to be sensitive to the claims of contemporary physics. One example of the interaction between physics and philosophy of time that was mentioned in Section 2 was Newton’s bucket argument, which used the observed effects of acceleration to argue for absolute motion (and thus absolute space and time). Another example mentioned above was the worry that the A-theory conflicted with special relativity. The latter has proved especially influential in contemporary metaphysics of time and so deserves some further discussion.

According to standard presentations of special relativity, there is no fact of the matter as to whether two spatially separated events happen at the same time. This principle, which is known as the relativity of simultaneity , creates serious difficulty for the A-theory in general and for presentism in particular. After all, it follows from the relativity of simultaneity that there is no fact of the matter as to what is present, and according to any A-theory there is an important distinction between what is present and what is merely past or future. According to presentism, that distinction is one of existence—only what is present exists.

A different way of describing the relativity of simultaneity involves the combination of two claims:

- the claim that whether two spatially separated events happen at the same time depends on the reference frame you use to describe them, and

- the claim that no reference frame is privileged.

This way of putting the relativity of simultaneity requires a new bit of technical jargon: the notion of a reference frame. For our purposes, a reference frame is nothing more than a coordinate system that is used to identify the same point in space at different times. Someone on a steadily moving train, for instance, will naturally use a reference frame that is different from someone who is standing on the station platform, since it is natural for the person on the train to think of themselves as stationary, while for the person on the platform it seems obvious that they are moving.