Mormon Battalion

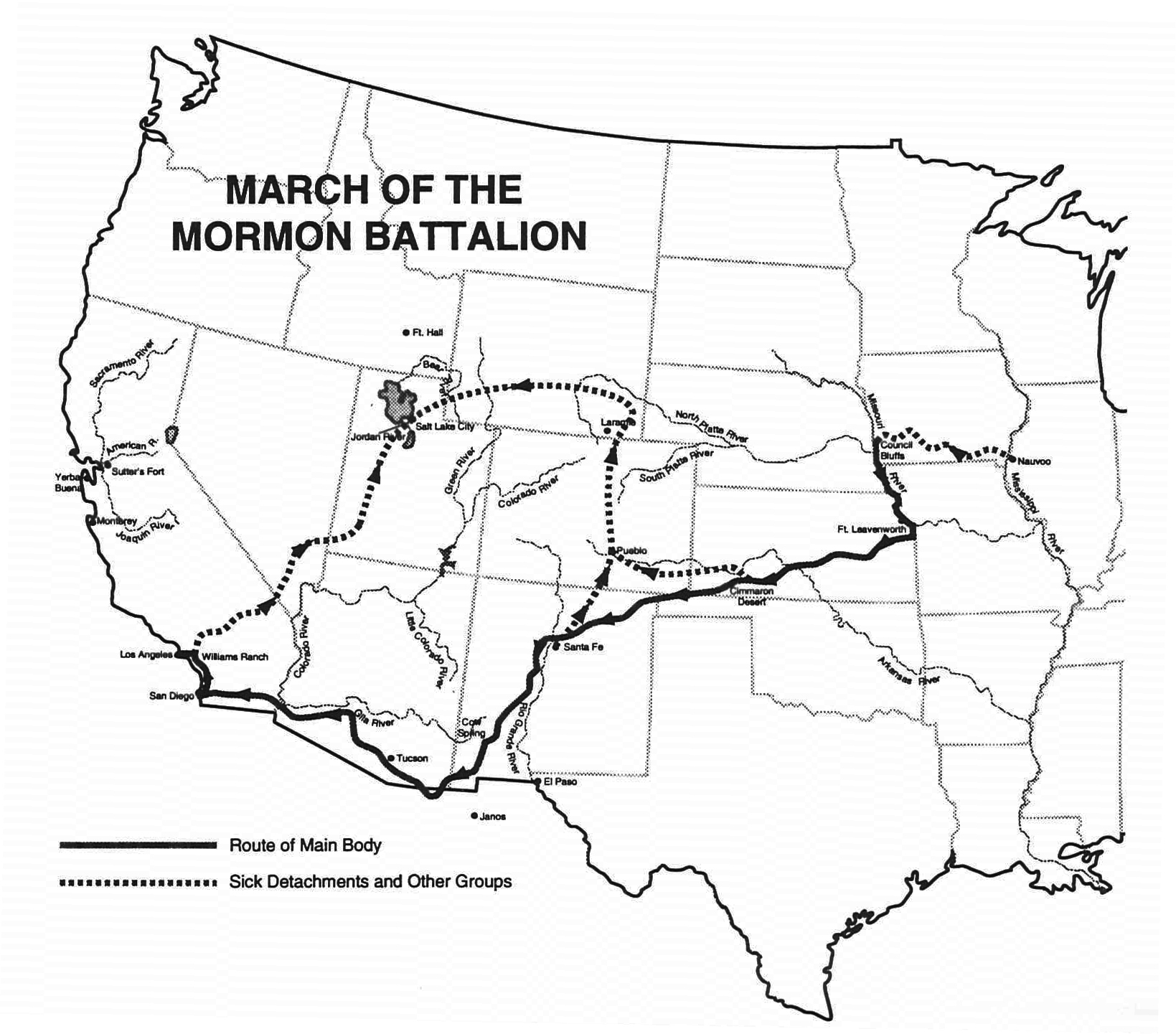

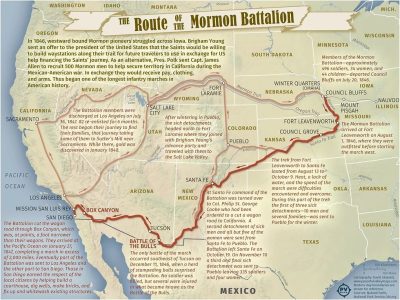

The Mormon Battalion , officially called the 1st Iowa Volunteers, was an infantry unit almost exclusively made up of Latter-day Saint (sometimes called Mormon) men and a few women who undertook the longest infantry march in U.S. military history and explored vast regions of New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The invitation to serve was actually the result of talks between leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints living on the East Coast of the United States, and U.S. Government officials. Jesse C. Little , presiding elder of the Church in the eastern United States, met with President Polk and offered Latter-day Saint assistance in exploring and fortifying the American West in return for monetary help. Polk proposed enlisting Latter-day Saint men to fight in the controversial U.S.-Mexican War. Under Polk's orders Captain James Allen met with the Church leaders in Iowa and Nebraska and asked for five hundred men. In exchange, the impoverished Saints, who had just been driven from their homes in Nauvoo, Illinois , received much needed funds to finance their trek west.

The Saints had many reasons not to enlist. The U.S. government had failed to protect them from mobs in Missouri and Illinois which had driven them from their homes and massacred hundreds. They were also about to cross the plains to an unknown land somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. However, Brigham Young , then President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles encouraged the men to enlist. He knew that the money they would earn would help their families and other poor Mormon Pioneers . He also knew that it would show the U.S. that members of the Church were still loyal to their country.

On July 16, 1846 , 541 men enlisted in the army and were organized into what was dubbed the Mormon Battalion. Some of the men’s wives and families joined them. There were 32 women and about 50 children who accompanied the battalion. The army hired 20 as laundresses. Brigham Young encouraged the men to be the best soldiers in the army, to be clean, neat, and polite. He prophesied to them that if they obeyed God’s commandments, they would not have to fight.

The Mormon Battalion left a few days after enlistment. It was difficult for many of them to leave their wives and children on the plains of Iowa, without homes, and with the task of crossing the country to Utah. However, Brigham Young assured the men that the Church would take care of their families until their return.

The Battalion traveled to Fort Leavenworth to get supplies, and then began a long trek southwest to California. The Mormon Battalion completed the longest infantry march in U.S. military history, over 2,000 miles. When they finally reached the Pacific Ocean on January 29, 1847 , some six months later, they were overjoyed. Along the way they endured sickness, thirst, hunger, and strife, plus some hostile military leaders who did not like the "Mormons." In New Mexico, a small contingent of seriously ill men departed the company and went to Pueblo, Colorado.

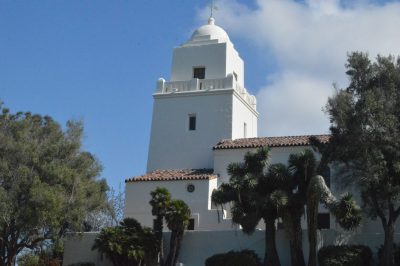

Brigham Young's prophesy came true, for by the time the Battalion arrived in California to aid in the war, it was over, and many of the men were assigned to work in California to finish out their year of service. The closest they had come to battle was in November of 1846, when the company was attacked by a herd of wild bulls in southern Arizona. The so-called "Battle of the Bulls" resulted in no deaths, two injuries, and much needed meat for the men. They also nearly engaged the Mexican army near the present-day Arizona-Mexican border, but the Mexican soldiers abandoned their posts at the approach of the battalion. Once in California, they built Fort Moore, a courthouse in San Diego, and made bricks and built houses in southern California. A monument and visitor's center stand as reminders of the work of the Battalion in exploring and settling California.

All of the members of the Mormon Battalion were released from duty on July 16, 1847. A few reenlisted for another eight months, but most began their journey back to Utah to be with their families. On their way back, many helped in building flour mills and sawmills for money to send to their families. Men of the Mormon Battalion were also the first to discover gold at Sutter’s Mill, starting the Gold Rush .

See Mormon Emigrant Trail

See Mormon Battalion Center at San Diego

External Links

- Mormon Battalion - Wikipedia

- Ol' Buffalo Mormon Battalion Page

- Mormon Battalion Association

- New Mormon Battalion site opens in San Diego, Caifornia, USA See also

- Mormon History

Navigation menu

- View source

Personal tools

- MormonWiki Home

- MormonWiki Articles

- Articles Needed

- Recent changes

- Random page

- More Good Foundation

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

In other languages

- This page was last edited on 29 January 2022, at 13:47.

- Privacy policy

- About MormonWiki

- Disclaimers

“From Iowa to Immortality: A Tribute to the Mormon Battalion,” Ensign, July 2007, 22–27

From Iowa to Immortality:

A Tribute to the Mormon Battalion

By Elder Lance B. Wickman

Of the Seventy

In January 1993, as the Church prepared for the open house and dedication of the San Diego California Temple, I found myself thinking about the men of the Mormon Battalion, who had arrived in San Diego in January 1847 after one of the longest, most torturous marches in military history. I am not sure why my thoughts turned to them. I had no ancestor who marched in their ranks. Perhaps it was my own experience as a combat infantryman that brought this feeling of kinship. Perhaps it was something more. Whatever the reason, I felt we could not dedicate this temple without doing something to remember the sacrifice of the Mormon Battalion. I called a friend who was active in one of the Mormon Battalion commemorative associations. I asked him if on the morning of the first day of the open house we could have a color guard of men in battalion uniform and a solitary bugler playing “To the Colors” as the American flag was raised for the first time over these sacred premises. “No band and no speeches,” I said, “just the bugler and the color guard.”

The morning dawned cool and blustery in the wake of a Pacific storm. A few of us gathered at the base of the flagpole and watched the Stars and Stripes flutter into full expanse as it caught the freshening breeze. The mesmerizing notes of the bugle floated across the tranquil temple grounds. In that moment I felt them there—the men of the battalion—formed one last time in silent ranks as the flag of the land they had served so valiantly rose above the temple that represented the Zion they had sought so earnestly. Tears filled my eyes. Truly, San Diego in winter can seem like paradise.

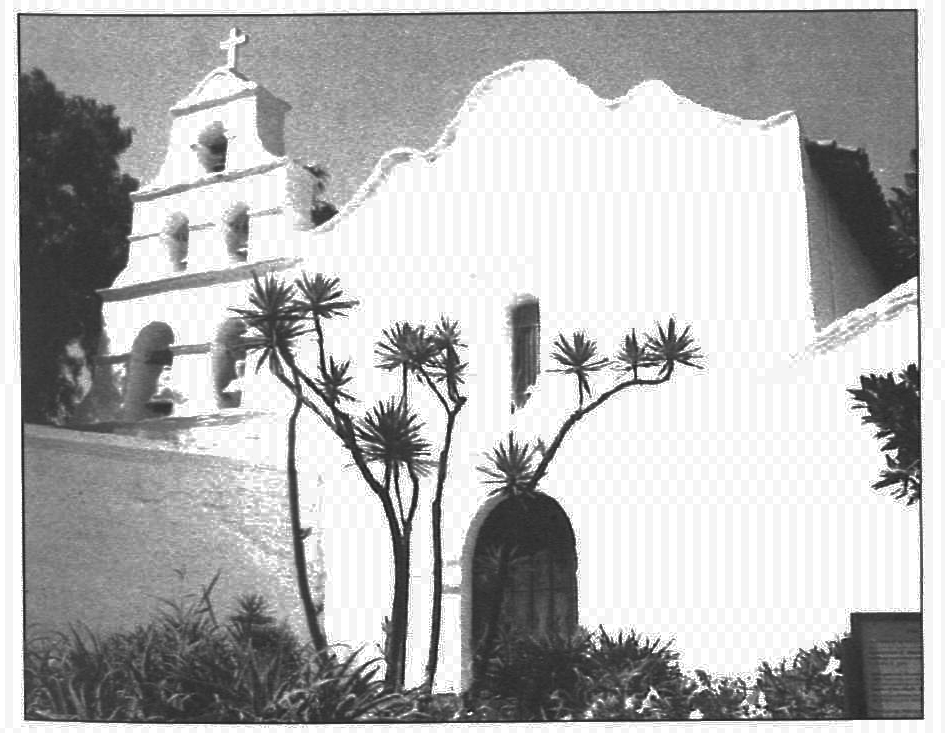

It must have seemed like paradise on that January day in 1847 to the half-starved 335 men and 4 women—many barefoot or shod only in rags or rough cowhide—who straggled into the little mission of San Diego. Daniel Tyler, Third Sergeant, Company C, Mormon Battalion, U.S. Army of the West, recorded his first impression: “Traveling in sight of the ocean, the clear bright sunshine, with the mildness of the atmosphere, combined to increase the enjoyment of the scene before us. … January there, seemed as pleasant as May in the northern States, and the wild oats, grass, mustard and other vegetable growths were as forward as we had been used to seeing them in June. The birds sang sweetly and all nature seemed to smile and join in praise to the Giver of all good.” 1

An Incongruous Story

The column of unkempt, shaggy-faced men must have seemed strangely out of place in such charitable surroundings. How could anyone be so threadbare and bedraggled in the natural cornucopia that was southern California in that time and season? It was inconsistent.

But, then, the whole saga of the Mormon Battalion is filled with contrasts: its origin as a military unit drawn from destitute refugees struggling for survival on the Iowa prairies; its roster formed from the unlikely—even bizarre—combination of hard-bitten Regular Army officers and the peace-seeking adherents of a despised and misunderstood religious sect; the willingness of these men to leave wives and families bereft in an untamed wilderness to serve a country that had turned its back on them when the Saints were persecuted in Missouri and Illinois; their long, long walk in the sun across prairie, mountain, and trackless desert; their willingness to suffer unspeakable privations; their vibrant faith in their God, their prophet, and, eventually, in their tough and austere army commander—Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke. The entire drama is incongruous—incongruous and inspiring.

As out of place as these men may have appeared upon their arrival at San Diego, as exhausted and subdued as they may have seemed in taking those last few agonizing steps in a trek of 2,000 miles, theirs is a story of courage and sacrifice that has few equals.

The U.S.–Mexican War was a long time ago. Military victories by American Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, plus the payment of $15 million by the United States, ultimately acquired the territory that later became the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. Yet history must also testify that equal, if not greater, honor belongs to an unheralded band of “citizen soldiers” recruited on the plains of Iowa. Theirs was unlike any other unit ever formed in the history of the United States Army—a battalion of Saints. This band of 500 men and a few women and children fired not a shot in anger, except at a herd of rampaging bulls. True to the prophetic promise made to them by President Brigham Young, not one of them was lost to hostile action, although 20 lost their lives due to the privations they suffered. But their work in carving out a wagon road with picks, shovels, and even their bare hands across the barren deserts of the American Southwest—a road which thousands would later follow en route to the fabled riches of California—did as much to secure these vast territories to the United States as all the storied military deeds of the war with Mexico.

The Mormon Battalion

The story of the organization of the Mormon Battalion is a tender one. June of 1846 found 15,000 Latter-day Saints strung out across Iowa in a half dozen or more makeshift encampments. Forced to leave their comfortable homes in their own city, Nauvoo the Beautiful, they had endured a tragic exodus across Iowa. Many had died of starvation, exposure, and disease during the cold winter and wet springtime. They had no homes, no property, and no clothing except what they carried in their wagons or wore upon their backs. Food was scarce. Some were bitter at the disinterest shown by the U.S. government in their plight. By crossing the Mississippi River, these pioneers had left the United States, following their leaders west to a destination they knew not, to a place where they hoped to live in peace.

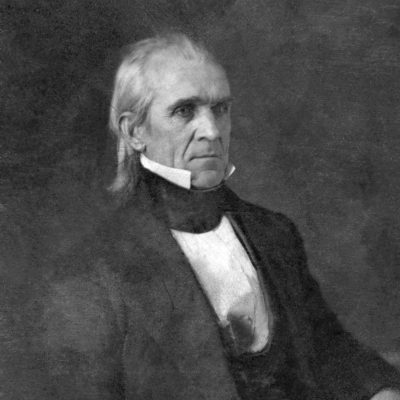

Into such desperate circumstances rode Captain James Allen, a cavalry officer, on June 26, 1846. The United States had declared war on Mexico, and President James K. Polk was calling for 500 Mormon volunteers to march to Fort Leavenworth, in present-day Kansas, and then to California on a one-year U.S. Army enlistment.

The Saints camped at Mount Pisgah were incredulous when they heard Captain Allen’s request. Surely, after all the governmental disinterest, even disdain, they had endured, this same government could not now be serious in such a preposterous proposal! Not only did they feel they owed nothing to the United States, but what would wives and children do if their husbands and fathers marched away on such an extended journey? How could they possibly face such an uncertain future?

But President Brigham Young, then at Council Bluffs, saw things differently. For one thing, the soldiers’ pay and uniform allowances would provide a much-needed source of income to purchase necessary food and supplies for the trek west. More than that, their country had called. Despite the government’s indifference to their plight, the Saints were still Americans, and America needed them. Touching is this personal account by Daniel B. Rawson: “I felt indignant toward the Government that had suffered me to be raided and driven from my home. … I would not enlist. [Then] we met President Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball and [Willard] Richards … calling for recruits. They said the salvation of Israel depended upon the raising of the army. When I heard this my mind changed. I felt that it was my duty to go.” 2

It was as simple as that. The prophet of the Lord had said they were needed, so they enlisted. On Saturday, July 18, 1846, the recruits were brought together by the rattle of snare drums. President Young and members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles met with the officers, commissioned and noncommissioned, in a grove of trees. Brother Brigham admonished them to be “fathers to their companies and manage their men by the power vested in the priesthood.” 3 A merry dance was held, accompanied by William Pitt’s brass band. Then the mood grew more somber as a young woman with light hair and dark eyes and a beautiful soprano voice sang the poignant and melodic words,

By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept.

We wept when we remembered Zion. 4

Many eyes glistened with tears. The next day was Sunday. On Monday morning they marched away—soldiers on an odyssey from which some would not return for a year, some for two or three years, some for almost a decade. A few would not return at all.

The Mormon Battalion made one of the longest treks in United States history—2,000 miles one way.

Trials and Suffering

The trials suffered by the members of the Mormon Battalion cannot be captured adequately by the written word. For one thing, the men of the battalion were ordered to march in virtual tandem with a group of Missourians under the command of the infamous Colonel Sterling Price—the same Colonel Price who had driven the Saints from their homes in Missouri a decade earlier. The Missourians refused to share rations until the battalion’s acting commander, Lieutenant Andrew Jackson Smith, threatened to “come down upon them with artillery.” 5

Then there was the battalion members’ suffering at the hands of the medically incompetent army doctor George B. Sanderson, whose remedy for every ailment was a large dose of calomel. The men soon learned that the supposed cure was invariably worse than the disease. They would either suffer in silence or refuse to swallow the calomel, spewing it out once out of Dr. Sanderson’s sight.

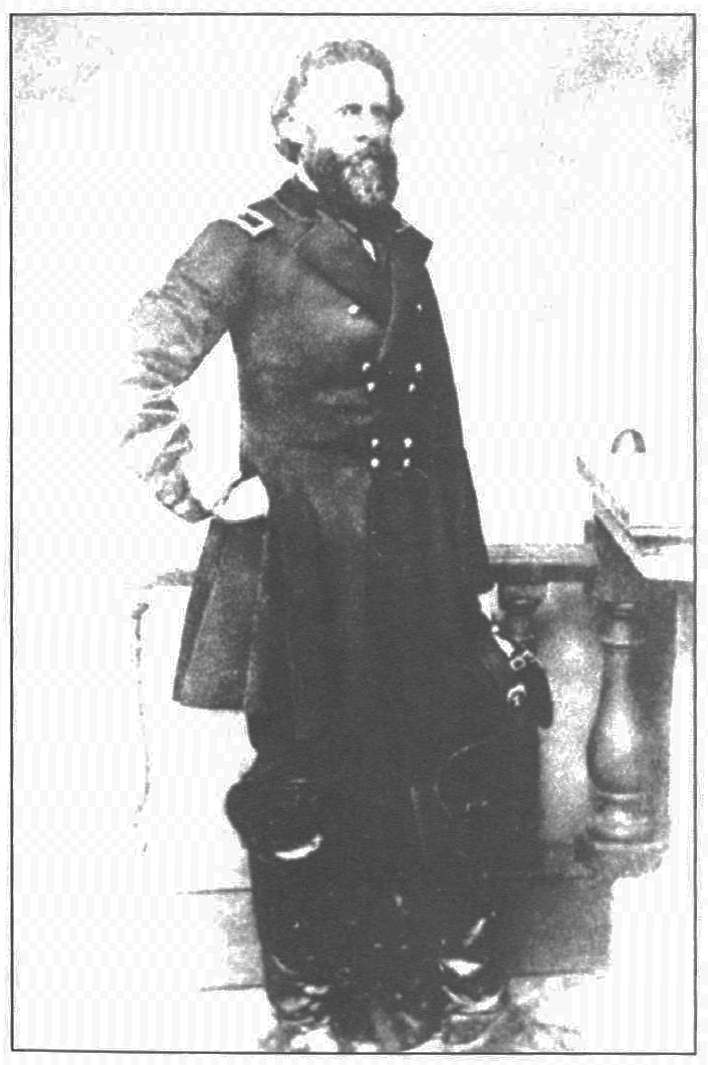

The changing leadership of the battalion presented yet another set of challenges. Shortly after they left Fort Leavenworth, the men learned that their beloved Captain Allen—who had recruited them and who had been a kindly and beneficent commander—had died. They were left under the temporary command of Lieutenant Smith, a man whose imperious and autocratic manner visited much misery upon them. In Santa Fe they received a new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, another cavalryman. He also was stern, and at first the men were dismayed. But with time they learned that, though he was tough as rawhide, Colonel Cooke cared for their welfare, and it was his toughness that helped them survive.

But most of all, it was the physical hardships that were so difficult to bear: searing sun, thirst, cold winds, hunger, thirst, sand, always more sand, thirst, rock, thirst. Six months into their trek, most of the men had traded away any spare clothing in exchange for food. Rags and pieces of hide took the place of shoes. Hair and beards were unshaven and uncombed. Skin was darkened to a deep, leathery brown. Bones and ribs of man and beast protruded through stretched flesh. The 339 survivors who at last struggled into San Diego that lovely midwinter day in January 1847 each bore a wild but strangely holy countenance. They had made it. They had come through for their country and for Zion. On the morning after their arrival, Colonel Cooke wrote: “The Lieutenant-Colonel commanding congratulates the Battalion on their safe arrival on the shore of the Pacific Ocean and the conclusion of their march of over two thousand miles. History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry.” 6

A March into History

The story of the Mormon Battalion does not end with its arrival in San Diego. Securing California for the United States, building the first courthouse in San Diego and building Fort Moore in Los Angeles, discovering gold shimmering in the mill race at Sutter’s Mill near Sacramento and thus bringing on the California gold rush of 1849—all of these were contributions of the Mormon Battalion. But the men of the battalion were not much interested in gold. Most just wanted to go home.

Significantly, the person who has come to best represent them was not a soldier at all, but a woman—Melissa Coray, the 18-year-old bride of Sergeant William Coray. Melissa was one of four women who marched all the way to San Diego with the battalion. Her odyssey continued as she and William migrated to Monterey, California, after William’s discharge, where she gave birth to a son, William Jr., on October 2, 1847. William Jr. died within a few months after his birth and was buried in Monterey. The couple then went to San Francisco and eventually on to the Salt Lake Valley, traveling more then 4,000 miles in all. When they arrived in Salt Lake City on October 6, 1848, Melissa was expecting their second child. William was ill with tuberculosis he had contracted in California but hoped to live long enough to see their child born. Happily, he did. Baby Melissa was born on February 6, 1849, about one month before William’s death. 7

Years later Melissa returned to California for a meandering trip through her own hall of memories. In 1901, when asked by a reporter about walking with the battalion, she simply said: “I didn’t mind it. I walked because I wanted to. My husband had to walk and I went along by his side.” 8 In 1994 the United States government dedicated a mountain in the Sierra Nevada Mountains east of Sacramento in her honor—Melissa Coray Peak, a fitting and permanent memorial to the men and women of the Mormon Battalion.

In every sense, they of the battalion had marched into history. Behind them would come many thousands of immigrants who would follow the trail they so painstakingly—and painfully—pioneered. They had raised “Old Glory,” the flag of their country, on the Pacific shore. And they had raised the ensign of Zion.

Mormon Battalion Time Line

February 4, 1846.

Latter-day Saint exodus from Nauvoo begins (below).

May 13, 1846

The United States declares war on Mexico.

June 26, 1846

Captain James Allen of the First U.S. Dragoons meets with Latter-day Saints camped at Mount Pisgah, Iowa, and asks for volunteers for the Mormon Battalion.

July 1, 1846

Captain Allen assures President Brigham Young that the Saints may encamp on U.S. lands, and President Young agrees to the formation of the battalion.

July 18, 1846

A dance is held at Council Bluffs, with music by William Pitt’s Brass Band.

July 20, 1846

The Mormon Battalion begins its march.

August 23, 1846

James Allen, newly promoted to lieutenant colonel and the battalion’s first commander, dies at Fort Leavenworth; Lieutenant A. J. Smith is acting commander.

October 9, 1846

General Alexander Doniphan (right), commander of American forces at Santa Fe, orders a 100-gun salute to honor the arrival of the Mormon Battalion in Santa Fe.

October 14, 1846

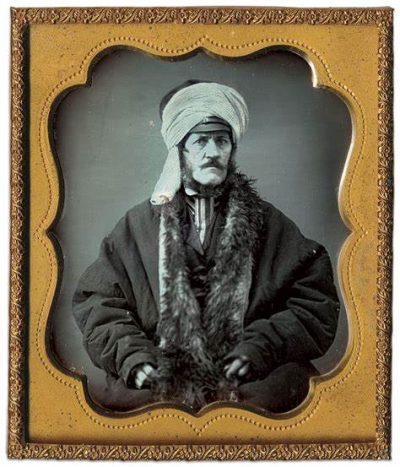

Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke (above) assumes command of the Mormon Battalion.

January 13, 1847

The Treaty of Cahuenga is signed between John Charles Fremont and General Andrés Pico, ending the conflict in California.

January 29, 1847

The Mormon Battalion arrives in San Diego.

July 24, 1847

The Latter-day Saint pioneer company, led by President Brigham Young, arrives in the Salt Lake Valley.

September 6, 1847

A letter from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles directs the former battalion members to find work in California and to come to Salt Lake in the spring. Nearly half go to Sutter’s Mill (right), and some are present when gold is discovered there on January 24, 1848.

February 2, 1848

The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ends the Mexican War; Mexico cedes territory including Utah to the United States.

April 12, 1848

The members of the Mormon Battalion who reenlisted for an additional six months are discharged; they pioneer the southern route to the Salt Lake Valley.

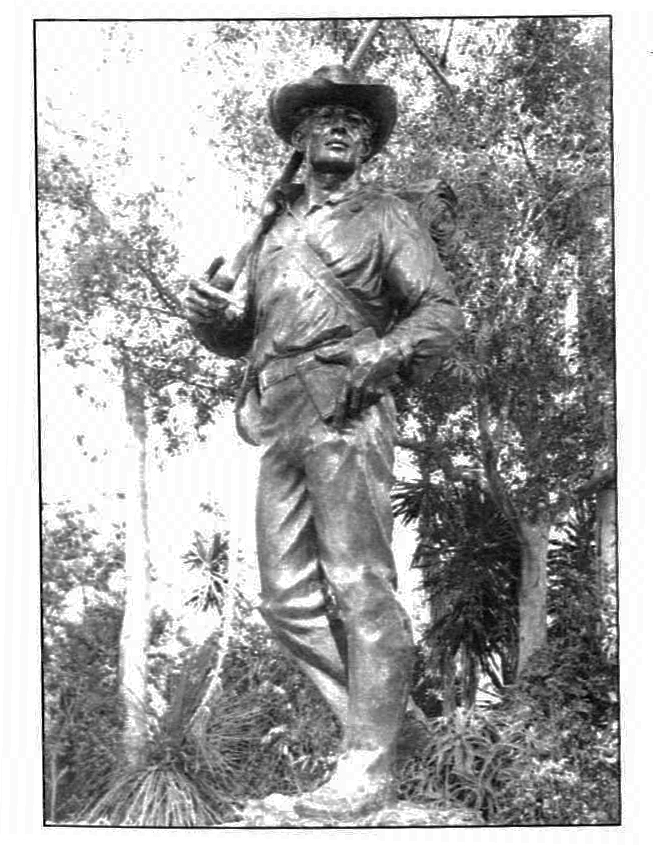

Detail from the Mormon Battalion Monument, by Gilbert Riswold

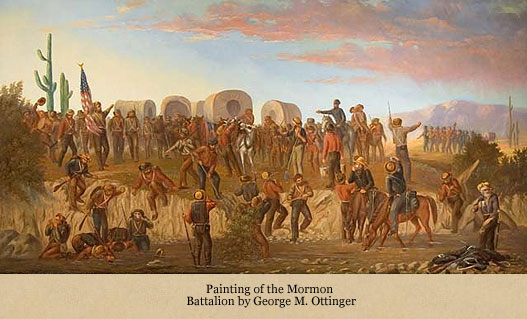

It was the physical hardships that were so difficult for the Mormon Battalion to bear: searing sun, cold winds, hunger, thirst, rock, sand, always more sand and more thirst. ( The Mormon Battalion, by George Ottinger, courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.)

President Brigham Young told the men they were needed, so they enlisted on July 16, 1846. (Illustration by Dale Kilbourn.)

Below: Two days after the men enlisted, a dance was held in the bowery at Council Bluffs, with music by William Pitt’s Brass Band. ( Mormon Battalion Ball, by C. C. A. Christensen, courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.)

Above right: Sugar Creek, by C. C. A. Christensen, courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.

Left: Soldiers left their loved ones, some not to be seen for years to come. (Illustration by Paul Mann.)

Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, used by permission of Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved; Alexander Doniphan, used by permission of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Gold Discovered at Sutter’s Mill, by Valoy Eaton.

Melissa Coray was the youngest of the four women who made the entire march with the Mormon Battalion (courtesy of International Society of Utah Pioneers).

The 339 survivors who at last struggled into San Diego that lovely midwinter day in January 1847 each bore a wild but strangely holy countenance. They had made it. ( Mormon Battalion, by John Fairbanks, courtesy of Museum of Church History and Art.)

How lessons from the Mormon Battalion mustering are relevant 175 years later

It was 175 years ago this month when the mormon battalion started its march across the u.s. what one group of researchers has done to verify who was in the battalion.

The accomplishments of the Mormon Battalion are indisputable — it helped create wagon roads as it marched through what is now southwest United States. After their enlistment was completed, battalion members helped with additional wagon routes connecting California, Nevada and Utah. Many followed those routes, and they impacted the boundaries of the United States.

“For a one-year enlistment, the Mormon Battalion had an outsized presence in the history of the United States, not just the history of the Church,” said Greg Christofferson, vice president of the Mormon Battalion Association .

It was in 1846 — 175 years ago — and Church members had left Nauvoo, Illinois, due to persecution and mob violence, and they were scattered across Iowa and into Nebraska as they prepared to head west to the Salt Lake Valley, then in Mexican territory. President Brigham Young had sent a request to U.S. President James K. Polk for assistance to move west. The call for 500 men to join a battalion to help fight in the Mexican American War wasn’t what he expected, either.

Their service helped them finance the move West, which prompted “Brigham Young to credit the battalion with being the ‘temporal salvation’ of the Church,” said Brandon Metcalf, a historian with the Church History Department. Beyond the financial benefit of being able to outfit their families and help others move west, they gained experiences from the nearly 2,000-mile march that would benefit them as the Saints settled in the West.

“It is difficult for us to even fathom such a journey in our comfortable age of air-conditioned automobiles, paved highways, availability of food and water, clothing and supplies, and technology that allows us to instantly communicate with loved ones and friends,” Metcalf said.

On the 175th anniversary of the Mormon Battalion’s march, which started on July 16, 1846, there are several lessons from their journey that can apply today. Also, researchers from the Mormon Battalion Association have been working with documents, including from the National Archives, to verify who served in the battalion.

Battalion lessons for today

While members of the Church today aren’t asked to march with a military unit across the desert, there’s more to learn from the Mormon Battalion’s experiences.

“The story of the Mormon Battalion is one of sacrifice, faith and perseverance that is relevant to our day,” said Metcalf.

- Trust the wider vision of the prophets

Many of the pioneer Saints were apprehensive about enlisting and it wasn’t until Brigham Young supported the enlistment effort that people started signing up. It seemed counterintuitive to many.

“Ultimately, each of the promises given to the battalion by Brigham Young and members of the Twelve before they departed were fulfilled: they escaped difficulties, were never required to engage in warfare, and their expedition ‘result[ed] in great good, and our names handed down in honorable remembrance to all generations,’” Metcalf said.

- Perseverance in adversity

The call to join the U.S. Army and help in the Mexican American War wasn’t convenient, and the 2,000-mile march across desert wasn’t easy. They were being asked to leave their families and help in the war with Mexico.

“Participants noted that the request to enlist in the battalion was ‘quite a hard pill to swallow’ feeling insulted by the request coming from a government that failed to defend the Saints through years of brutal persecution,” Metcalf said.

During the march, they pushed wagons over sand and through mountains and many times had very limited water and food.

“Yet, throughout the ordeal they relied on their faith in the Lord and the prospect of reuniting with their families and establishing Zion in the West. Their story continues to inspire us today by offering lessons on the importance of faith, commitment and the resilience of the human spirit,” Metcalf said. “As we learn about their sacrifice, we draw strength from their examples of overcoming extreme adversity that inspire us to push forward along our own weary marches.”

- Faith in the Lord

“All of us encounter deep, sandy roads or march along barefoot and hungry carrying heavy loads of emotional, physical or spiritual trials,” Metcalf said. “It requires faith and the help of the Lord to overcome mortal suffering and recognizing as did one battalion member, that ‘nothing could have saved our lives but the unseen hand of Almighty God.’

“Just as the Lord saw the battalion through their trials, He will do the same for us even when our trials seem hopeless and unsurmountable.”

Digging into the records

But who, exactly, was in the Mormon Battalion?

As men were enlisting with the Mormon Battalion, Church leaders kept various rosters and lists of those who enlisted or volunteered, in part to make sure the families were cared for. Those lists and the Compiled Military Service Record Card have been frequently used to help identify who was in the Mormon Battalion, but they had men listed who volunteered, but never went, along with other errors, said Laura Anderson, the Mormon Battalion Association executive director.

Several years ago, Anderson heard that the Mormon Battalion muster and payroll records were in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. — official military records that had been previously thought lost.

The muster lists were created every two months, accounting for each person’s service, and included if they were sick, sent with a detachment, discharged, died or deserted, Anderson said. Anderson, with help from other researchers, volunteers and those at the National Archives, was able to locate the records. She’s been back to the National Archives about 10 times since. (She shared her experiences at RootsTech and it is available online at familysearch.org. )

They also found bounty land applications and pension records. Bounty lands were a reward for the completion of military service of 160 acres. As Utah wasn’t available for bounty land assignments, most of the battalion members sold their land, Anderson said. Pension records helped researchers find additional family members.

With multiple trips to the National Archives and other records available online, Anderson and other researchers have been able to verify the vast majority of those who were in the battalion, follow them through the records kept on the journey and when they got home, and connect them to their families.

“So it is a melding of all of these different records to allow us to uniquely identify” the battalion members, Anderson said.

One man they’ve recently researched is Peter Fife. He had been listed on a roster for Company B, and his obituary noted he was “one of the Mormon Battalion.” His name was eventually dropped from lists of those with the battalion as he wasn’t on a military roster. Thanks to other online and digitized records, including several journals of others during that time, the researchers were able to verify that Fife was with the battalion.

“Since Peter is not on the roster as a soldier, it is possible Peter is a teamster or aide, although no documentation for either of those possibilities has been found — yet,” Anderson said.

As researchers have been connecting individuals to the records, they’ve been adding the information to FamilySearch and also have plans to make their research available on the Mormon Battalion Association’s website.

“We know who the 496 men were,” Christofferson said, noting that an occasional nickname offers a challenge to the researchers. “We can identify 496 [names] that the records agree on.”

They’ve also been able to dispel myths about the battalion, too, including the men were literate, why they didn’t have uniforms and that all who went were members of the Church.

Anderson found many records where the men had to sign with an “X” — instead of signing their names — and it was countersigned by an officer.

“No volunteer unit in the Mexican War was given uniforms except by their state,” Anderson said. As the Saints weren’t enlisting in a particular state, they didn’t get uniforms. They were able to send a portion of their uniform allowance they received at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, back to their families.

They’ve found a man who joined the Mormon Battalion at Fort Leavenworth who wasn’t a member of the Church. Through their research, they haven’t found if he ever joined the Church, she said.

“And the thing that excites me more than anything else is the fact that we are still figuring these people out,” Anderson said.

Several events along the Mormon Battalion’s trail are being planned for the 175th anniversary by a variety of organizations, including in Santa Fe, New Mexico; Tucson, Arizona; and San Diego and Yuma, California. The Mormon Battalion Association will be part of the Military Appreciation Day in August at Camp Floyd, Utah. A historical symposium is scheduled in August at Council Bluffs, Iowa. See mormonbattalion.com for information.

For more about the Mormon Battalion, the Church has the Mormon Battalion Center in San Diego, California, which has both in-person and virtual tours. Also, see an interactive map from the Church History Department at history.churchofjesuschrist.org/maps/mormon-battalion?lang=eng

The Trek West

The trail from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Great Salt Lake Valley was approximately 1,300 miles long and would ultimately lead 70,000 Latter-day Saint pioneers to the West.

Locations along the Trail

Pioneer stories, pioneer exhibits.

- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

California Saints

A 150-year legacy in the golden state, richard o. cowan and william e. homer, the epic march of the mormon battalion: 1846–47.

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 59–80.

The story of the Mormon Battalion began with the desperate need the Saints had, both individually and collectively, for cash. Having been driven from Nauvoo in the cold winter, many were sick and destitute. During the spring and summer of 1846, they scattered throughout Iowa, many working as day laborers to scrape enough money together to outfit themselves for the trek west.

To assist the Pioneers with their monetary needs, Church leaders in Nauvoo publicly announced in a circular their desire to obtain a government contract to build a chain of stockade forts along the Oregon Trail. [1] But given the prevailing anti-Mormon attitude and the tense situation with Mexico, government leaders would not sanction any plan that would give the Saints so much military influence in the West.

Behind-the-Scenes Negotiations

On 26 February, Brigham Young wrote to Jesse C. Little, a thirty-year-old New Englander, appointing him to preside over the Eastern States Mission. President Young continued to encourage California settlement, instructing Little: “If our government shall offer any facilities for emigrating to the western coast, embrace those facilities if possible.” [2]

In Philadelphia, Little was introduced to Col. Thomas L. Kane, who understood the Saints’ dilemma, and the two became fast friends. Kane wrote a letter to the vice president of the United States urging the government to aid the Saints, who, he testified, “still retain American hearts, and would not willingly sell themselves to the foreigner.” [3]

Little arrived in Washington, D.C., on 21 May 1846, one week after the United States declared war on Mexico. Two days later, with the assistance of A. G. Benson, Little was able to secure an appointment with Amos Kendall, the former postmaster general who had sought to extort Brannan and who still wielded considerable influence in the U.S. capital. Kendall “thought arrangements could be made to assist our emigration by enlisting one thousand of our men, arming, equipping, and establishing them in California to defend the country.” [4]

On 27 May, Kendall informed Little that he had broached the subject with President James K. Polk, who by this time “had determined to take possession of California,” and was considering, with his cabinet, the possibility of using Latter-day Saint volunteers to “push through and fortify the country.” [5] The president and his cabinet had already dispatched Col. Stephen W. Kearny, then stationed at Fort Leavenworth, to travel via Santa Fe to California.

By 1 June, Little had not received any definite word on the proposed use of Latter-day Saint troops, so he wrote a lengthy letter to the president in which he requested “some pecuniary assistance” for the westward migration of his persecuted people. “We would disdain to receive assistance from a foreign power,” Little wrote, “unless our government should turn us off in this grant” and thus “compel us to be foreigners.” [6]

President Polk’s diary entry for the following day records that Colonel Kearny was specifically “authorized to receive into service as volunteers a few hundred of the Mormons who are now on their way to California. . . . The main object of taking them into service would be to conciliate them, and prevent them from assuming a hostile attitude towards the U.S. after their arrival in California.” [7] On 3 June, Jesse Little had a three-hour interview with the president, who stated that he had received Little’s letter and wished to help him but had not worked out all the details.

That same day, however, President Polk and the secretary of war finalized the orders to Colonel Kearny: “It is known that a large body of Mormon emigrants are en route to California, for the purpose of settling in that country. You are desired to use all proper means to have a good understanding with them, to the end that the United States may have their co-operation in taking possession of and holding, that country. . . . You are hereby authorized to muster into service such as can be induced to volunteer; not, however, to a number exceeding one-third of your entire force.” He indicated that the Saints would be paid like other volunteers and be able to nominate some of their own men to serve as officers. [8] On 5 June, President Polk, in another interview, informed Little of this decision. [9] Recruiting the Battalion On 19 June, just a week before he left Fort Leavenworth for Santa Fe with his first contingent of troops, Kearny complied and dispatched Capt. James Allen to the Latter-day Saint camps in Iowa to raise five hundred volunteers. Accompanied by three dragoons (armed cavalry), Captain Allen arrived at Mount Pisgah just one week later. There was some grumbling among the Saints about being asked to serve a country that had allowed them to be expelled; some even believed that this was a plot to destroy them. Nevertheless, Brigham Young immediately endorsed the proposal and went with Allen throughout the scattered camps, chastening the naysayers and soliciting volunteers. On 7 July, President Young “addressed the brethren on the subject of raising a Battalion to march to California.” Jesse C. Little, who had just arrived the day before from the East, spoke to the same gathering. As a result, sixty-six men volunteered. [10] Captain Allen explained that forming a Mormon battalion “gives an opportunity of sending a portion of their young and intelligent men to the ultimate destination of their whole people, and entirely at the expense of the United States, and this advanced party can thus pave the way and look out the land for their brethren to come after them.” [11]

Furthermore, as Brigham Young concluded, “the Mormon Battalion was organized from our camp to allay the prejudices of the people, prove our loyalty to the government of the United States, and for the present and temporal salvation of Israel.” Battalion members would be able to send money to their families in Iowa, which would help finance their westward migration. [12]

In less than a month, the quota was filled. The volunteers enlisted into service on 16 July 1846 for a period of twelve months. Brigham Young instructed them that after being disbanded they could work on the coast if they wished, but holding to his original plan for the Saints’ settlement, he emphatically reminded them that the next temple would not be built there, but in the Rocky Mountains, “where the brethren will have to come to get their endowments.” He further explained that the Saints were going to the Great Basin, where they would be safe from mobs and that the Battalion would “probably be dismissed about 800 miles from us.” [13]

No one could have known just how difficult the twelve months of Battalion service would be. Throughout the march, conditions were generally bad. Nevertheless, President Young promised the recruits that none would be killed in battle “if they will perform their duties faithfully without murmuring and go in the name of the Lord, be humble and pray every morning and evening.” [14]

The approximately five hundred volunteers were joined by thirty-five women—some of them serving as army laundresses— and many children. The Latter-day Saint soldiers buttressed Kearny’s “Army of the West.”

The Battalion marched from Council Bluffs on 21 July and recorded its first fatality the following day, when Samuel Boley became ill and died. They endured unbearably hot weather, torrential rain, and even a tornado. Many became sick from exposure and lack of provisions before they marched the two hundred miles to Fort Leavenworth for supplies.

On 29 July they marched through St. Joseph, Missouri, and found the townspeople astounded that the Latter-day Saints had volunteered to serve a United States government that had turned a deaf ear to their cries for redress. On 1 August, the day after the Brooklyn dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay, the Battalion reached Fort Leavenworth and was amply outfitted— a mixed blessing since each soldier would have to carry a heavy pack. A Missourian, George B. Sanderson, became Battalion doctor; the Saints viewed this as a most unfortunate appointment. Each man received his allotted forty-two dollars clothing allowance for the year, but instead of purchasing new uniforms, many sent the money back to aid their families and the general emigration effort. The paymaster noticed that the Battalion men, unlike many illiterate soldiers, could sign their names. In fact, the several detailed diaries kept made it one of history’s best-documented military marches. They also conducted religious services throughout their march—an unusual practice for soldiers.

Along the Santa Fe Trail

The Battalion followed the old Santa Fe Trail through what is now Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico into Santa Fe. The trail “was no mere line of ruts connecting two towns, two cultures. It was a perilous cruise across a boundless sea of grass, over forbidding mountains, among wild beasts and wilder men, ending in an exotic city offering quick riches, friendly foreign women and a moral holiday.” Travelers “knew only darkness, fatigue, cold and sunburn, the insistent wind, the drenching downpour, the lone danger of guard duty while the wolves howled from the hills and the skulking Comanche fitted an arrow to his bowstring.” [15]

Upon leaving Fort Leavenworth on 13 August, the Battalion’s original leader, James Allen, who was popular with the men, became ill, remained behind, and died ten days later. The agreement with the Battalion was that if for any reason they lost their commander, they were to choose one of their own to take his place. They chose Capt. Jefferson Hunt.

Less than a week after they left Fort Leavenworth, a powerful storm hit them. “About sun down,” wrote Henry Standage, “the wind commenced blowing very hard accompanied with large drops of rain and continued to blow till our tents were all blown down and our cooking utensils scattered all over the Prairie.” [16] Robert Bliss, a fellow soldier, described the storm this way: “We had hardly time to pitch our tents before the storm came down upon us, it tore our tents from their fastenings, overturned our light wagons and prostrated men to the ground. The vivid lightning and the roar of the thunder and hail caused horses and mules to break from their fastenings and flee in every direction on the wide prairie.... Lieutenant Ludington’s carriage was overturned with his wife and Mother in it and our Orderly’s Carriage was sent before the storm 15 or 20 rods and he in pursuit of his wife in it.” [17]

On 29 August, two weeks after the Battalion departed Fort Leavenworth, Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith of the regular army intercepted the Battalion and took command from Captain Hunt, a move which violated the agreement between the U.S. Army and the Church. Lieutenant Smith, a West Point graduate, disliked Mormons, and the Saints viewed his appointment as another unfortunate choice. The volunteers concluded that there was an unholy alliance between Smith and his accomplice, George B. Sanderson, the Battalion doctor. Smith, who looked on the LDS volunteers and their accompanying women and children as unfit for army service, confronted them with long, forced marches, making them sick. Then Dr. Sanderson concocted medicines of calomel and arsenic which, the men believed, either cured or killed. Brigham Young counseled the recruits by letter to turn to faith and priesthood ordinances for healing, and “let surgeon’s medicine alone.” [18]

Marching just a few days ahead of them was a large group of Missouri volunteers, some of whom were members of mobs that drove the Saints from Missouri eight years before. The two groups were sufficiently separated that, with the exception of brief confrontations at the crossing of the Arkansas River and at Santa Fe, they had no trouble with each other. The Indians, who fought against the incursions of the Whites both the year before and the year after, were strangely quiet that year. They ambushed, killed, and took the scalps of a few Missourians, but the Battalion was never bothered.

Through this part of the trek, the biggest problems were forced marches and dust. Pvt. Azariah Smith, who had just celebrated his eighteenth birthday during the march, recorded the following in his diary: “Tuesday Sept 1st. 1846. . . . I and Thomas went ahead this morning as my eyes were so sore that I could not travail in the dust of the Battalion. We travailed 15 miles and camped by a Spring on the prairy, called the Lost Spring. We arived at the Spring about 2 oclock, dry and dusty. . . . Monday Sept 14 th . . . . The time goes very well with me except my eyes being very Sore.” [19]

On 10 September, the Battalion met a group of messengers en route to Fort Leavenworth with the report that on 18 August Kearny, who had been promoted to general, had taken Santa Fe without firing a shot. He wanted the volunteers to go directly to Santa Fe rather than taking the longer route via Bent’s Fort in Colorado. Lieutenant Smith followed orders and took the more direct but more difficult route through the Cimarron Desert.

On 16 September, Smith ordered a group of fifteen sick families, who he believed could not make the difficult march, to leave the main body and proceed instead to Pueblo, Colorado. There they joined fourteen families of Saints from Mississippi who had set up a semi-permanent camp while awaiting the main body coming overland with Brigham Young.

In the desert there were long stretches without water, except for occasional pools polluted with the urine and dung of animals. An increasing number of men and animals became sick. During the next three weeks there were only two days during which they had fresh water.

On 2 October the Battalion received word that General Kearny would discharge them unless they reached Santa Fe by 10 October. Consequently, the officers decided to split the command into two detachments: the able and the feeble. The able-bodied were force-marched to Santa Fe, arriving on 9 October. The feeble entered the town three days later. When the first group arrived they learned that Kearny had already pushed on toward California and had left Alexander W. Doniphan in charge at Santa Fe. General Doniphan had come to the defense of the Latter-day Saints at a crucial time during the Missouri persecutions eight years before. Now, as the Battalion marched into Santa Fe’s central plaza, he ordered his men to give them a one-hundred-gun salute from the rooftops of surrounding adobe buildings.

A New Wagon Road to the Coast

When General Kearny learned of Colonel Allen’s death, he appointed Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke, another West Point graduate, to take command of the Mormon Battalion at Santa Fe. Having anticipated the glories to be earned on the battlefield, Cooke was likely disappointed with this assignment to shepherd a group of inexperienced volunteers. His initial impression of the Battalion was quite discouraging: “It was enlisted too much by families; some were too old,—some feeble, and some too young; it was embarrassed by many women; it was undisciplined; it was much worn by travelling on foot, and marching from Nauvoo, Illinois; their clothing was very scant;—there was no money to pay them,—or clothing to issue; their mules were utterly broken down; the Quartermaster department was without funds, and its credit bad; and mules were scarce.” [20] These were hardly the criteria for an efficient battle-force. Nevertheless, as a recent historian has pointed out, the Battalion had “hidden yet great potential.” [21]

The preferred route from Santa Fe to the Pacific Coast was the Old Spanish Trail—through what is now central Utah to Southern California. There were trails on the more direct route from New Mexico through the Gila Valley of Arizona, but wagons had not been taken over them. Kearny, who left Santa Fe on 25 September intending to take wagons with him over the Gila route, soon abandoned them to make better time. He appointed Colonel Cooke and the Battalion to open the wagon road.

After the harsh conditions caused a second “sick detachment” to be dispatched to Pueblo, the Battalion left Santa Fe on 19 October with 397 men and twenty-five wagons, each wagon pulled by eight mules. Though their march would last another ninety days, the quartermaster was able to give the men only enough flour, sugar, coffee, and salt for sixty days, along with rations of salt pork for thirty days and soap for twenty.

The original plan was for the Battalion to follow Kearny’s route as closely as possible. Two weeks later, however, Cooke received word from Kearny advising him that wagons could not cross the mountains on the most direct route to the Gila and consequently directed him to go farther south along the Rio Grande before turning west. This more southerly route was completely unexplored, and it was here that the Battalion made a significant and far-reaching contribution.

The rations were never increased but were often decreased. Though the Battalion passed through numerous Mexican villages, the curious natives were generally too suspicious or poor to part with food, except for a few apples and grapes. The terrain consisted of such deep sand, in so many places, that the animals could not pull wagons through without assistance. Battalion members, already burdened with heavy packs, had to use ropes to assist the animals in pulling the wagons much of the way. “Today the Captain had us divided off ten to a wagon, to push them up hills and over bad places,” Azariah Smith recorded. “We have only half rations now of flour and live cheafly on beaf which is very poor and tough.” [22]

On 10 November, about 250 miles from Santa Fe, fifty-five men became too weak to travel further and were sent back to Pueblo to join the other invalids. Now numbering about 360, including women and children, the Battalion continued down into the Rio Grande Valley. Along the way they saw intricate irrigation systems, some several miles long. Their observations were fortuitous, as the knowledge of irrigation later became a necessary survival skill both in California and in Utah.

On 13 November the volunteers left the banks of the Rio Grande and headed southwest to get around the end of the mountains. A strong north wind brought very frigid temperatures. “It was exceedingly cold last night,” Colonel Cooke recorded in his diary, “water froze in my hair this morning whilst washing.” [23]

About a week after leaving the Rio Grande, the Battalion’s scouts reported that they could not find adequate sources of water or a suitable pass ahead. A few of the men, therefore, hoping to attract someone who could recommend a better route, scaled a nearby hill and built a signal fire. A group of helpful Mexicans told them that just over a hundred miles farther south was an established westward trail passing through some settlements in what is currently northern Mexico. Cooke decided to take this detour. This decision again antagonized the Battalion; they felt it was not consistent with their mission to go straight to the coast. Daniel Tyler recalled that “a gloom was cast over the entire command.” That evening, fifty-five-year-old David Pettigrew encouraged the men to pray that the Lord might change the colonel’s mind, that he “might not lead up into battle or directly through the enemies strong holds where in all probability they would give up battle.” [24]

Nevertheless, the next morning Cooke led the Battalion directly south toward the Mexican settlements. After going only two miles, however, the trail turned southeast, and Cooke became alarmed that he would get too far to the east and run into unforeseen problems. That would rob him of his chance to carve a trail to the West Coast. Cooke “arose in his saddle and ordered a halt. He then said with firmness: ‘This is not my course.’“ [25] He swore that he would be “damned if he was going all around the world to get to California.” [26] He then directed the bugler to “blow the right,” thus turning the troops due west. Witnessing this, David Pettigrew blissfully exclaimed, “God bless the Colonel!” Tyler recalled that the colonel “glanced around to discern whence the voice came, and then his grave, stern face for once softened and showed signs of satisfaction.” [27]

During this part of the journey, the men curried favor with their commander through an ingenious solution to the problem of dragging the wagons through deep sand. A double file of foot soldiers went ahead of the wagons, stomping down the sand in ruts so the wagon wheels had firmer ground to roll over. The double column was rotated every hour. This unconventional plan worked rather well and was therefore followed from this point on.

After passing over the Continental Divide, the Battalion, on 30 November, lowered their wagons over a two-hundredfoot precipice in Guadalupe Canyon and emerged into what is now southeastern Arizona.

While marching along the San Pedro River on 11 December, the Battalion engaged in its only fight—a battle with wild bulls. Herds gathered along the line of march. Some of the bolder animals attacked the soldiers and gored several mules to death. The men had been ordered to march with their weapons unloaded, but they now loaded them to defend themselves, and “the rattle of musketry was for once heard all along the line.” [28]

Colonel Cooke wrote in his diary: “The animals attacked in some instances without provocation, and tall grass in some places made the danger greater.” Tyler was standing next to Cpl. Lafayette Frost when they saw an “immense coal-black bull” about one hundred yards away charging toward them. Frost aimed his musket deliberately but did not fire until the beast was only six paces away. Colonel Cooke feared that “one man’s ‘ignorance with some stubbornness’ was about to receive a terrible retribution.” But when he saw the huge bull lifeless at their feet, “how changed must have been his feelings.” [29]

The bulls became even more ferocious when wounded. Dr. William Spencer shot one animal five times: twice through the lungs, twice through the heart, and once through the head, yet the culprit “would alternately rise and fall and rush upon the doctor” until it was shot a sixth time directly between the eyes. Reports of the number of wild bulls killed ran from twenty to sixty, and one writer put the figure at eighty-one. [30]

At this point in the journey, a decision had to be made. The Battalion could march through Tucson for needed rest and supplies and shorten their route by one hundred miles. But Tucson was a village of five hundred, garrisoned by two hundred Mexican troops with cannons. After a cursory consideration, Cooke decided to take the shortcut and capture Tucson.

Upon the Battalion’s arrival, the two armies engaged in conversing, posturing, gesturing, threatening, arresting of emissaries, and so forth. But there was no gunfire. Finally, on 16 December the Battalion marched into town and found that the Mexican soldiers had abandoned it. The natives were friendly and shared their food. The soldiers in turn were respectful, though Cooke confiscated two thousand bushels of grain left behind by the Mexican Army.

The next leg of the trek was especially trying. Water became extremely scarce. For several days the men and their animals trudged along with no water except for occasional small, muddy ponds. On 19 December the main body of soldiers did not camp until after dark, but to cope with their exhaustion, some “stopped without leave being worn out. The Brethren were passing by at all hours through the night,” Henry Standage recorded in his journal, “still hoping that the Command had found water, travelling two or three miles at a time and resting.” [31]

When someone complained about the bawling, thirstcrazed mules, Colonel Cooke curtly rejoined, “I don’t care a damn about the mules, the men are what 1 am thinking of.” [32] When some pools of freshly fallen rainwater were finally found, Battalion men not only quenched their own thirst but also helped their fellow soldiers. For example, Lieutenant Rosencrans went back along the line “on a mule loaded with Canteens of water relieving those of Co C. who had lain out.” [33] Out of these difficult circumstances emerged an increasing mutual respect between Colonel Cooke and his men.

The Battalion reached the Gila River near the Pima Indian villages on 21 December, completing their assignment to open a wagon road from the Rio Grande. The significance of this accomplishment cannot be overestimated: they pioneered a new route through previously unexplored deserts between the mountainous Apache strongholds on the north and the Mexican frontier settlements on the south. This route would become a key link in a proposal for a southern transcontinental railroad. This in turn would make the 1853 Gadsden Purchase necessary, bringing what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico into the United States.

Colonel Cooke thought it might be easier to float supplies down the Gila River than to carry them to the river’s confluence with the Colorado. A raft was built of two wagon boxes and loaded with foodstuffs. However, the river’s sandbars soon overcame the raft and the precious food, both of which were lost. At this same time, on New Year’s Day 1847, Battalion members received from a group of eastward-bound travelers their first word that the colony of Saints from New York had successfully landed and was preparing a base of operations at San Francisco Bay.

After crossing the Colorado into California on 10 January, things got worse. Although General Kearny had dug some wells for the trailing Battalion, many had become dry, so new ones had to be dug. Colonel Cooke described the days between 12 and 16 January as the hardest of all. Tyler concurred:

We here found the heaviest sand, hottest days and coldest nights, with no water and but little food. . . . At this time the men were nearly barefooted; some used, instead of shoes, rawhide wrapped around their feet, while others improvised a novel style of boots by stripping the skin from the leg of an ox. . . . Others wrapped cast-off clothing around their feet. [34]

As the Battalion left the desert and entered the Coast Range, they came to Box Canyon, which was too narrow for their wagons. Even though most of their tools had been lost with the makeshift raft on the Gila River, the men now had to chisel a passage through “a chasm of living rock.” Colonel Cooke set the example by wielding one of the axes. [35]

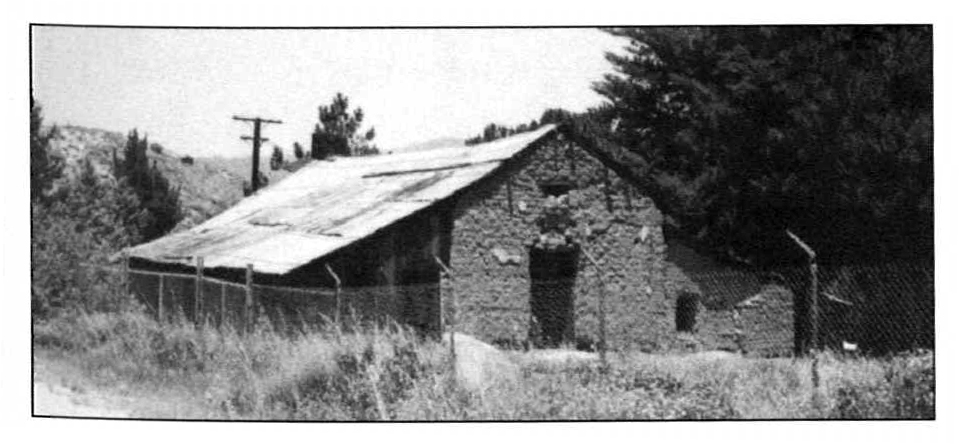

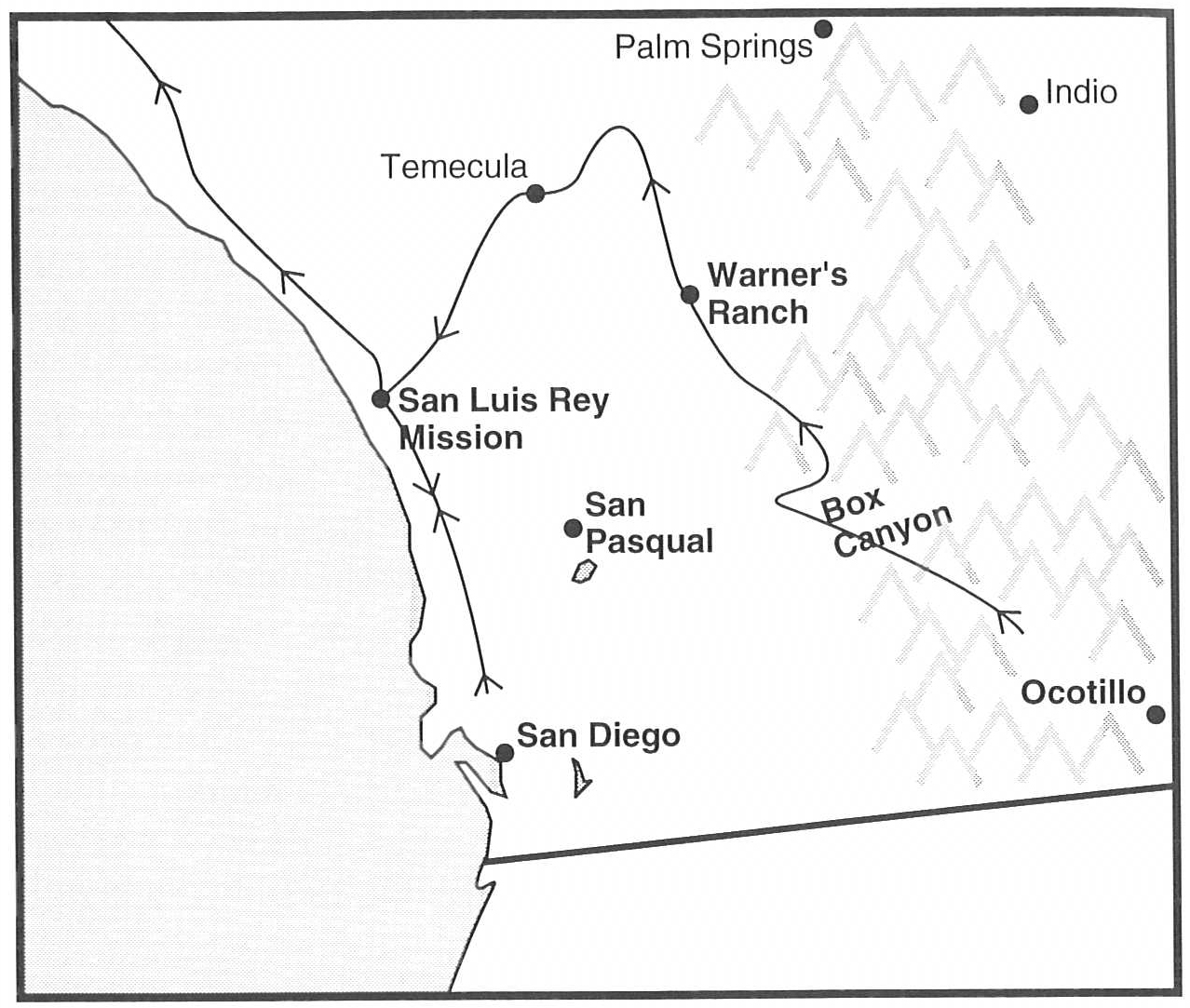

On 21 January, the Battalion reached Warner Ranch (now in the Cleveland National Forest, northeast of Escondido), Mormon Battalion route into the San Diego area where one Anglo man and three hundred Indians lived. Warner, upon hearing of their approach, hid all his foodstuffs, leaving the soldiers to dine on unsalted beef and a few pancakes made by the Indians. However, there were hot and cold springs—healing balm for aching feet, limbs, and joints.

Upon leaving the ranch, the soldiers passed without incident by San Pasqual, a small village where just over a month before, General Kearny’s soldiers had encountered a group of Mexican “Californio” defenders who had killed Capt. Benjamin D. Moore and seventeen of his men. The Mormon Battalion first headed toward Los Angeles then received orders to detour into San Diego instead. By this time, California’s landscape had taken on the luscious, emerald-green coat of January. As they marched through picturesque wooded hills and verdant winter valleys, they marveled at the fauna and flora, including vast seas of yellow-flowered mustard greens, which became new elements in their diet.

Sighting the Pacific

On 27 January 1847 the Mormon Battalion sighted the Pacific Ocean. Every soldier who kept a diary attempted to put his feelings into words. Typical is the entry of Daniel Tyler:

The joy, the cheer that filled our souls, none but worn-out pilgrims nearing a haven of rest can imagine. Prior to leaving Nauvoo, we had talked about and sung about “the great Pacific Sea,” and we were now upon its very borders, and its beauty far exceeded our most sanguine expectations. . . . The next thought was, where, oh where were our fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, wives and children. [36]

On 29 January, almost exactly six months after the Brooklyn landed at San Francisco, the march ended. The Latter-day Saint soldiers were quartered near the Catholic mission some five miles outside San Diego. Both the Battalion’s grueling land march and the Brooklyn’s arduous sea voyage had taken six months. Both groups had known danger, storms, sickness, shortness of provisions, and an equal number of deaths. And both were happy to be at their Pacific destination.

Despite Col. Philip St. George Cooke’s initial misgivings about taking over a ragtag group of worn-out volunteers, he became attached to the Battalion and inspired by their admirable courage and long-suffering over the epic 1,100-mile trek from Santa Fe to San Diego. The day after arriving, Cooke wrote the following commendation, which was subsequently read to the Battalion:

The Lieutenant-Colonel commanding congratulates the battalion on their safe arrival on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, and the conclusion of their march over two thousand miles. History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry. Half of it has been through a wilderness where nothing but savages and wild beasts are found, or deserts where, for want of water, there is no living creature. There, with almost hopeless labor we have dug deep wells, which the future traveler will enjoy. Without a guide who had traversed them, we have ventured into trackless table-lands where water was not found for several marches. With crowbar and pick and axe in hand, we have worked our way over mountains, which seemed to defy aught but the wild goat, and hewed a passage through a chasm of living rock more narrow than our wagons. To bring these first wagons to the Pacific, we have preserved the strength of our mules by herding them over large tracts, which you have laboriously guarded without loss. The garrison of four presidios of Sonora concentrated within the walls of Tucson, gave us no pause. We drove them out, with their artillery, but our intercourse with the citizens was unmarked by a single act of injustice. Thus, marching half naked and half fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made a road of great value to our country. Arrived at the first settlement of California, after a single day’s rest you cheerfully turned off from the route to this point of promised repose, to enter upon a campaign, and meet, as we supposed, the approach of an enemy; and this, too, without even salt to season your sole subsistence of fresh meat. . . . Thus, volunteers, you have exhibited some high and essential qualities of veterans. [37]

As one might expect, Cooke’s words were “cheered heartily by the Battalion.” [38]

Impressive monuments in California and Utah, as well as a staffed visitors center in San Diego, would in later years celebrate the Mormon Battalion’s accomplishments. But their service did not end with their epic march. They had much more to contribute to early California. Their community work and their key roles in one of the state’s most historic events—the discovery of gold—are also stories worth telling.

[1] History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 7:570.

[2] Quoted in Journal History, 6 July 1846 (hereafter JH); LDS Church Archives.

[7] The Diary of James K. Polk, ed. Milo Milton Quaife (Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1910), 1:444,446.

[8] U.S. Congress, Senate, 30th Cong., 1st sess., 1847–48, Senate Executive Document no. 60, as quoted in John F. Yurtinus, “A Ram in the Thicket: The Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1976), 34–35.

[9] JH, 6 July 1846.

[11] “Circular to the Mormons” quoted in JH, 26 June 1846.

[12] JH, 14 August 1846.

[13] Willard Richards Diary, 14 July 1846 and 18 July 1846, as cited in Yurtinus, 53–54, 59.

[14] Elden J. Watson, Manuscript History of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: E. J. Watson, 1971), 264.

[15] Stanley Vestal, The Old Santa Fe Trail (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1939), preface, viii.

[16] Frank A. Colder, The March of the Mormon Battalion: From Council Bluffs to California (New York: The Century Co., 1928), 148.

[17] Robert S. Bliss Diary, 19 August 1846; typescript, LDS Church Archives.

[18] Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War (Glorieta, N. Mex.: Rio Grande Press, 1881), 146; see also Susan E. Black, “The Mormon Battalion: Conflict Between Religious and Military Authority,” Southern California Quarterly 74, no. 4 (winter 1992): 313–28.

[19] Azariah Smith, The Gold Discovery journal of Azariah Smith, ed. David L. Bigler (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press^ 1990), 23, 26.

[20] Philip St. George Cook, The Conquest of New Mexico and California in 1846–1848 (Chicago: Rio Grande, 1964), 91.

[21] Dwight L. Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 166.

[22] Smith, 47.

[23] Philip St. George Cooke, William Henry Chase Whiting, Francois Xavier Aubry, Exploring Southwestern Trails 1846–1854, ed. Ralph P. Bieber (Clendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1938), 105.

[24] Henry W. Bigler Diary, Book A, 48; typescript in possession of Larry C. Porter, Brigham Young University.

[25] Tyler, 207.

[26] Henry W. Bigler, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West, ed. Erwin G. Gudde (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962), 28.

[27] Tyler, 207.

[28] B. H. Roberts, The Mormon Hattalion: Its History and Achievements (Salt Lake City: The Deseret News, 1919), 38.

[29] Tyler, 220.

[30] Roberts, 38–39; Tyler, 219–20.

[31] Colder, 197.

[32] William Coray Diary, 19 December 1846, quoted in Yurtinus, 415.

[33] Colder, 197.

[34] Tyler, 244–45.

[35] Roberts, 47–48.

[36] Tyler, 252.

[37] Cooke, Conquest, 197.

[38] Tyler, 255.

Contact the RSC

185 Heber J. Grant Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 801-422-6975

Helpful Links

Religious Education

BYU Studies

Maxwell Institute

Articulos en español

Artigos em português

Connect with Us

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

- Search for:

Cooke’s Wagon Road

To san diego.

Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke led the Mormon Battalion out of Santa Fe with the mission to (1) march the battalion to California, (2) bring the wagons Gen. Kearny had left behind to California and (3) to “open a wagon road to the Pacific.” Gen. Kearny specifically selected Cooke for this assignment because of Cooke’s experience as a veteran frontier army dragoon officer, who was an expert in logistics, foraging, managing livestock, marching over inhospitable terrain, and keeping his troops ready for combat. The 37 year-old Cooke, a West Point graduate at age 18 (class of 1827), was an imposing figure, standing 6’4”. He was known as a tough, strict disciplinarian, rigid task-master, thorough planner, harsh, but fair to his men. He was adamant on following orders at any cost, with zero tolerance for failure, unprofessionalism or disobedience. His was a daunting task to lead a hastily assembled and meagerly supplied contingency of heavily laden wagons and fatigued, untrained civilian volunteers on the most challenging and demanding part of the Battalion’s trek – crossing 1100 miles of harsh, uncharted mountains, deserts and rivers of the Southwest. The Battalion now depended on their individual strength and will power combined with Col. Cooke’s leadership in order to succeed.

Departure from Santa Fe

On Oct. 19, 1846, the Battalion left Santa Fe with 30 wagons: 15 government mule wagons each pulled by a team of 8 mules, 6 ox-drawn wagons pulling heavy supplies, including shovels, picks, crow-bars for road tools, 4 mule-drawn wagons for the command staff, quartermaster (Lt. A.J. Smith), medical corp (Dr. George Sanderson) and paymaster (Major Jeremiah Cloud), and an additional 5 wagons purchased by the soldiers to help carry their equipment. The quartermaster had secured full rations of flour, sugar, coffee and salt for 60 days; salt pork for 30 days and soap for 20 days. They also herded 28 beeves (cattle) and some 300 long-legged sheep (churros) for fresh meat. In order to reduce weight in the wagons, Cooke left some heavy equipment behind, such as skillets and ovens.

Because the maps available in 1846 (Tanner’s American Atlas and Augustus Mitchell’s 1846 map of Texas, Oregon and California) lacked detail, Cooke declared, “I discovered that the maps are worthless; they can be depended on for nothing.” Cooke obtained several experienced reputable guides to act as pioneers (advanced scouts) for the Battalion to look for the best route for the wagon procession, campsites and sources of water: Pauline Weaver and Philip Thompson. Dr. Stephen Foster (Yale-educated medical doctor living in Santa Fe) was hired as chief interpreter and scout. Willard Hall, formerly of Doniphan’s 1st Missouri Mounted Volunteers, served as a scout, messenger, aide and assistant to Cooke. Other Mexican and Indian guides were only known by single names: Tasson, Chacon, Francisco and Appolonius. Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, son of Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau, members of the 1803 Lewis and Clark Expedition, was assigned to the Battalion by Kearny and joined the Battalion on Oct. 24 outside of Albuquerque. The most experienced and lead scout, famous mountain man Antoine Leroux, was originally with Kearny’s advanced troops, but was sent back to guide Cooke along Kearny’s route because of his familiarity with the Gila River valley.

Cooke’s Wagon Route Initiated

Traveling south from Santa Fe, Cooke followed the established 200 year-old El Camino Real that paralleled the Rio Grande River and connected Santa Fe with Chihuahua. It was an excruciating ordeal traveling over flat river bottoms, hills and sandy stretches that often required the heavy wagons to be double-teamed, pushed and pulled by the men through the rough terrain. On Nov. 2, the scouts found a note left by Gen. Kearny that read “Mormon Trail,” intending for the Battalion to follow his westward route. On that same day, Leroux arrived in camp and related to Cooke that Kearny’s route was too difficult for wagons and too arid for men and animals. Following Leroux’s recommendation, the Battalion took a route 80 miles to the south and then west 300 miles to intersect the San Pedro River.

On Nov. 9, Cooke made the assessment that in order to achieve the objectives of the Battalion he had to lessen the constraints and conserve limited rations. He ordered the 3rd Sick Detachment to Fort Pueblo. He discarded unnecessary equipment into several wagons: excess camp and cooking equipment and tent poles. The men used their muskets for tent poles. Messes were increased from 6 to 9 men. Excess mules and the spare 10 yoke of oxen were packed with loads of 60-80 lbs.

On Nov. 13, Cooke located a note from Leroux directing the Battalion off the established trail whereupon they commenced to blaze a new southwest road across the uncharted arid tablelands and deserts of New Mexico and Arizona. This marked the beginning of Cooke’s Wagon Road. With the scouts leapfrogging days ahead to find the best route for the wagons (flat ground) and water, Cooke realized he was heading too far southeast toward Mexico not California, so he instructed his bugler to “blow to the right,” and turned the Battalion to the southwest. The Battalion men considered this action an answer to their fervent prayers.

The march was exhausting with the men existing on half rations and very little water for days at a time. The men were stretched out for miles. Lewis Dent, civilian clerk to Maj. Cloud, recorded his poignant observations, “I saw athletic and vigorous men reduced, by thirst and fatigue, to the imbecility of children … their bodies attenuated and feeble; their faces bloated; their eyes sunken; their feet lacerated and bruised, mechanically moving forward, without a murmur and without an object; the latter having been lost sight of in the gloomy contemplation of their present helpless condition.” When water was found, the stronger men filled canteens and retraced their tracks to bring water to their struggling comrades who were strung out for miles behind. On Nov. 28, Cooke sent his scouts to locate Guadalupe Pass for passage through the rugged New Mexico mountain range. Unable to locate the Pass, the Battalion was forced to make a road through steep canyons for the wagons. Supplies were packed onto 150 mules so the emptied wagons could be lowered down steep, narrow ledges and ravines using ropes. After passing over the Guadalupe Mountains, the Pass was found just a mile away, which greatly angered Cooke regarding the competency of the scouts. Due to a relative abundance of wild cattle from deserted ranches and wild game (bear, deer, antelope and fish), the men ate well on fresh meat, much of which was jerked for consumption on the trail.

Across Arizona

The Battalion intercepted and followed a trail first used by Col. Juan Bautista de Anza in 1775 to the San Pedro River. On Dec. 11, the legendary “Battle of the Bulls” occurred in which the Battalion column fought off an assault by several dozens of wild bulls (reported numbers range from 20-81) from the abandoned San Bernardino Ranch. Confusion erupted resulting in several men and mules being gored and wagons overturned. 12 downed bulls fed the Battalion for several days. Upon approaching the Mexican town of Tucson purportedly armed with 130-200 Mexican troops and 2 or 3 brass cannons, Cooke communicated back and forth with the Mexican commander, Capt. Antonio de Comaduran, in which neither side wanted armed conflict. Since conditions set by both sides were unacceptable to the opposing side, Cooke took the offensive and marched through Tucson rather than going 100 miles around the town. The fatigued Battalion was relieved that the Mexican garrison had left the night before, thus avoiding any direct confrontation. From Tucson to the Gila River, men and livestock suffered greatly from lack of water. Many men were walking with footwear made from rawhide, canvas, or pieces of blanket and old cloth. The Battalion intersected Kearny’s route, referred to as the Dragoon Trail, near the friendly Pima Indian camps.

Here the Battalion traded buttons, old clothes and ragged shirts for bread cakes, corn, beans, squash, molasses and watermelon. Further along the Gila River were the equally hospitable Maricopa Indians, who were also eager to trade. Christmas dinner consisted of cold beans, pancakes and pumpkin sauce with watermelon as the treat of the day. Already on half rations, the food supply was running low. The men were reduced to chewing strips of rawhide as they marched. Mesquite seeds were gathered and eaten raw, roasted, or ground into meal with their coffee mills to make bread and pudding.

On Jan. 1 Cooke decided to lighten the mules by floating 2500 lbs of flour, pork and provisions on a pontoon raft constructed by lashing two of the water-tight wagons between 2 dry cottonwood logs. The heavy barge ran aground on shallow sandbars of the Gila River and had to be unloaded, so it could go downriver. Only a small portion of these unloaded supplies, including road tools, were recovered.

Crossing into California

Entering California required the dangerous crossing of the Colorado River, which was about a half-mile wide and an average of about 4 feet deep. This crossing was accomplished Jan. 10-11 near Yuma in a slow and methodical maneuver using the previously constructed pontoon raft to ferry men and equipment. Wagons forded the river pulled by mule teams. Three wagons had to be abandoned on the California side to be retrieved at a later date. The Battalion proceeded with 7 of the original 25 government wagons. Several water wells were dug along the way. The long forced marches, lack of rest and water caused a repeat of previous stretches in November and December when the men were strewn out for miles with their stronger comrades retracing their path with canteens of water for the fatigued stragglers. After trudging a hundred miles through desert terrain, they passed Carrizo Creek, camped at the Palm Spring oasis, and then traveled to the verdant Vallecito Valley where they recouped for a day.

On Jan. 19, the Battalion struggled over a difficult pass (Campbell Grade), made a 180º turn to the east, followed a dry creek bed and then encountered a narrow defile, subsequently named Box Canyon. The cliffs narrowed to where it became impassible for the wagons, requiring men to disassemble and carry two wagons through the canyon. The sides of the cliffs then had to be chiseled with crowbars, axes and spades to allow the remaining wagons to pass through. A 20-foot wall of rock then had to be bypassed by hewing a large rock enabling the wagons to climb out of the creek bed and traverse along a mountain slope before reentering the creek bed, which led to Blair Valley. Here the Battalion camped, but the next day, Jan. 20, they had to chisel out a wagon path over a ridge out of Blair Valley. This pass was later named Foot and Walker Pass. The Battalion proceeded north through the flat San Felipe Valley to Warner’s Ranch, where they enjoyed several days of good meals and rest, including soaking in hot springs.

Arrival at San Diego