Contemporary Issues Within Caribbean Economies pp 235–264 Cite as

Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts

- David Mc. Arthur Baker 3

- First Online: 09 June 2022

284 Accesses

The Caribbean economy is highly dependent on the tourism industry and the protection of the natural and cultural attractions on which it depends is critical. To address this concern, this chapter provides a snapshot of the progress that has been made on sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean region. There is now more demand from the traveling public for industries to be environmentally friendly and in order to continue to use tourism as a means of economic advancement, sustainable practices must be adopted. The evidence suggests that there are great economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts of tourism in the Caribbean region that are both positive and negative. The actions of the accommodations sector are commendable but there is the need for all major stakeholders to better manage the negative impacts of tourism development. The Caribbean Tourism Organization has developed a policy framework which consists of guiding principles and integrated policies regarding sustainable tourism development, The Caribbean Sustainable Tourism Policy and Development Framework. A shock, such as COVID-19, can lead to economic collapse as communities heavily dependent on tourism have no capacity to respond to the loss of their primary revenue source. However, in order to strengthen the resilience of small island tourism development, the Caribbean region is transitioning toward community-driven solutions through innovation, employee training, upgrades, greater digitalization, and environmental sustainability.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Abdool, A. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of tourism: A comparative study of two Caribbean communities (Doctoral dissertation, Bournemouth University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/76947.pdf

Adrian, S. C. (2017). The impact of tourism on the global economic system. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 17 (1), 384–387.

Google Scholar

Albattat, A. (2017). Current issue in tourism: Diseases transformation as a potential risk for travelers. Global and Stochastic Analysis, 5 (7), 341–350.

Anderson-Fye, E. P. (2004). A “Coca-Cola” shape: Cultural change, body image, and eating disorders in San Andrés, Belize. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 561–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1068-4

Article Google Scholar

Aref, F., Gill, S. S., & Farshid, A. (2010). Tourism development in local communities: As a community development approach. Journal of American Science, 6 , 155–161.

Bakar, N. A., & Rosbi, S. C. (2020). Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science, 7 (4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.74.23

Baker, D. M. A. (2015). Tourism and the health effects of infectious diseases: Are there potential risks for tourists? International Journal Safety and Security of Tourism and Hospitality, 1 (12), 18. https://www.palermo.edu/Archivos_content/2015/economicas/journal-tourism/edicion12/03_Tourism_and_Infectous_Disease.pdf

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2018). Characteristic and intentions of cruise passengers to return to the Caribbean for land-based vacations. Journal Tourism – Revista de Turism, 26, 1–9.

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2021). Understanding residents’ opinions and support towards sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean: The case of Saint Kitts and Nevis. Coastal Business Journal, 18 (1), 1–29.

Becken, S. (2014). Water equity-contrasting tourism water use with that of the local community. Water Resources and Industry, 7 (8), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wri.2014.09.002

Becker, A. E. (2004). Television, disordered eating, and young women in Fiji: Negotiating body image and identity during rapid social change. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 533–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1067-5

Becker, A. E., Fay, K., Agnew-Blais, J., Guarnaccia, P. M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Development of a measure of “acculturation” for ethnic Fijians: Methodologic and conceptual considerations for application to eating disorders research. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47 (5), 754–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510382153

Behsudi, A. (2020, December). Wish you were here. Finance & Development . https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/12/pdf/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi.pdf

Bellos, V., Ziakopoulos, A., & Yannis, G. (2020). Investigation of the effect of tourism on road crashes. Journal of Transportation Safety & Security, 12 (6), 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2018.1545715

Bohdanowicz, P., Simanic, B., & Martinac, I. (2004, October 27–29). Sustainable hotels—Eco-certification according to EU Flower, Nordic Swan and the Polish Hotel Association. In Proceedings of the Regional Central and Eastern European Conference on Sustainable Building (SB04) . Warszawa, Poland.

Brewster, R., Sundermann, A., & Boles, C. (2020). Lessons learned for COVID-19 in the cruise ship industry. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 36 (9), 728–735.

Brida, J. G., & Zapata, S. (2010). Cruises tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, 1 (3), 205–226.

Britton, S. (1989). Tourism, dependency, and development: A mode of analysis. Europäische Hochschulschriften 10 (Fremdenverkehr), 11, 93–116.

Bushell, R., & McCool, S. F. (2007). Tourism as a tool for conservation and support of protected areas: Setting the agenda. In R. Bushell & P. F. J. Eagles (Eds.), Tourism and protected areas: Benefits beyond boundaries (pp. 12–26). CABI International.

Butt, N. (2007). The impact of cruise ship generated waste on home ports and ports of call: A case study of Southampton. Marine Policy, 31 (5), 591–598.

Cannonier, C., & Burke, M. G. (2019). The economic growth impact of tourism in small island developing states-evidence from the Caribbean. Tourism Economics, 25 (1), 85–108.

Caribbean Hotel Association. (2014). Advancing sustainable tourism, a regional sustainable tourism situation analysis: Caribbean . https://caribbeanhotelandtourism.com/

Castillo-Manzano, J. I., Castro-Nuño, M., López-Valpuesta, L., & Vassallo, F. V. (2020). An assessment of road traffic accidents in Spain: The role of tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23 (6), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1548581

Castro, C. (2004). Sustainable development: Mainstream and critical perspective. Organization and Environment, 17 (2), 195–225.

Chang, C., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12 (9), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093671

Chappell, K., & Frank, M. (2020). The most tourism-dependent region in the world braces for prolonged Coronavirus recovery . Reuters. https://skift.com/2020/04/20/the-most-tourism-dependent-region-in-the-world-braces-for-prolonged-coronavirus-recovery/

Charles, D. (2013). Sustainable tourism in the Caribbean: The role of the accommodations sector. International Journal of Green Economics, 7 (2), 148–161.

Cheng, T. L., & Conca-Cheng, A. M. (2020). The pandemics of racism and COVID-19: Danger and opportunity. Pediatrics, 146 (5), e2020024836. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-024836

Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27 (6), 1274–1289.

Cole, S. (2014). Tourism and water: From stakeholders to rights holders, and what tourism businesses need to do. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22 (1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.776062

Cook, C. L., Li, Y. J., Newell, S. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Neel, R. (2018). The world is a scary place: Individual differences in belief in a dangerous world predict specific intergroup prejudices. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21 (4), 584–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216670024

Croes, R., & Vanegas, M., Sr. (2008). Cointegration and causality between tourism and poverty reduction. Journal of Travel Research, 47 (1), 94–103.

Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism.” Sustainability, 8 , 475–507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

Darma, I. G. K. I. P., Dewi, M. I. K., & Kristina, N. M. R. (2020). Community movement of waste use to keep the image of tourism industry in GIANYAR. Journal of Indonesian Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 3 (1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.17509/jithor.v3i1.23439

Deloitte. (2012). Sustainability for consumer business operations: A story of growth . https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Consumer-Business/dttl_cb_Sustainability_Global%20CB%20POV.pdf

Farmer, P. (2006). AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame . University of California Press.

Findlater, A., & Bogoch, I. I. (2018). Human mobility and the global spread of infectious diseases: A focus on air travel. Trends in Parasitology, 34 (9), 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.004

Ghadban, S., Shames, M., & Abou Mayaleh, H. (2017). Trash crisis and solid waste management in Lebanon-analyzing hotels’ commitment and guests’ preferences. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality, 6 (3), 1000169. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-8807.1000171

Gössling, S., Peeters, P., Hall, C. M., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Lehmann, L. V., & Scott, D. (2012). Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tourism Management, 33 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.015

Greening, A. (2014). Understanding local perceptions and the role of historical context in ecotourism development: A case study of Saint Kitts (Master’s Thesis, Utah State University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hanafiah, M. H., Harun, M. F., & Jamaluddin, M. R. (2010). Bilateral trade and tourism demand. World Applied Sciences Journal, 10 , 110–114.

Harry-Hernández, S., Park, S. H., Mayer, K. H., Kreski, N., Goedel, W. C., Hambrick, H. R., Brooks, B., Guilamo-Ramos, V., & Duncan, D. T. (2019). Sex tourism, condomless anal intercourse, and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 30 (4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000018

Haukeland, J. V. (2011). Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of national park management in Norway. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19 (2), 133–153.

Haywood, M. K. (2020). A post COVID-19 future—Tourism re-imagined and re-enabled. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762120

Homans, C. G. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63 (6), 597–606.

Hoppe, T. (2018). “Spanish Flu”: When infectious disease names blur origins and stigmatize those infected. American Journal of Public Health, 108 (11), 1462–1464. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645

Hung, C. H., & Wu, M. T. (2017). The influence of tourism dependency on tourism impact and development support attitude. Asian Journal of Business and Management, 5, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.24203/ajbm.v5i2.4594

International Ecotourism Society. (2004). The triple bottom line of sustainable tourism . https://www.coursehero.com/file/81910666/s1pdf/

Jamal, T., & Stronza, A. (2009). Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (2), 169–189.

Johnson, D. (2002). Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: A reality check. Marine Policy, 26 (4), 261–270.

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). The environmental, social and economic impacts of cruising and corporate sustainability strategies. Athens Journal of Tourism, 3 (4), 273–285.

Jordan, E. J. (2014). Host community resident stress and coping with tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Jordan, E. J., Lesar, L., & Spenser, D. M. (2021). Clarifying the interrelations of residents’ perceived tourism-related stress, stressors, and impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 60 (1), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519888287

Jordan, E. J., & Vogt, C. A. (2017). Appraisal and coping responses to tourism development-related stress. Tourism Analysis, 22 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14828625279573

Kaseva, M. E., & Moirana, J. L. (2010). Problems of solid waste management on Mount Kilimanjaro: A challenge to tourism. Waste Management & Research, 28 (8), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X09337655

Klein, R. A. (2011). Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18 (1), 107–118.

Korstanje, M., & George, B. (2020). Demarketing overtourism, the role of educational interventions. In H. Séraphin & A. C. Yallop (Eds.), Overtourism and tourism education (pp. 81–95). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Laville-Wilson, D. P. (2017). The transformation of an agriculture-based economy to a tourism-based economy: Citizens’ perceived impacts of sustainable tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, South Dakota State University). South Dakota State University Open Prairie. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2262/

Li, Y., & Galea, S. (2020). Racism and the COVID-19 epidemic: Recommendations for health care workers. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (7), 956–957. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305698

Lubin, D. A., & Esty, D. C. (2010). The sustainability imperative. Harvard Business Review, 88 (5), 42–50.

Lyneham, S., & Facchini, L. (2019). Benevolent harm: Orphanages, voluntourism and child sexual exploitation in South-East Asia. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 574 . Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/benevolent_harm_orphanages_voluntourism_and_child_sexual_exploitation_in_south-east_asia.pdf

Mackenzie, S., & Goodnow, J. (2020). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing micro-adventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 43 (10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773984

MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tourism Management, 66 , 387–404.

Mansfield, B. (2009). Sustainability. In N. Castree, D. Demeriff, D. Liverman, & B. Rhoads (Eds.), A companion to environmental geography (pp. 37–49). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305722.ch3

Mansfeld, Y., & Pizam, A. (2006). Tourism, security and safety . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Asif, M., Zia ul Haq, M., & Rehman, H. (2019). The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 16 (19), 37–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193785

Mawby, R. I. (2017). Crime and tourism: What the available statistics do or do not tell us. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 7 (2), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2017.085292

Miller-Perrin, C., & Wurtele, S. K. (2017). Sex trafficking and the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Women & Therapy, 40 (1–2), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2016.1210963

Minooee, A., & Rickman, L. (1999). Infectious diseases on cruise ships. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 29 (4), 737–743.

Murphy, P., & Murphy, A. E. (2004). Strategic management for tourism communities. Channel View Publications.

Nofriya, N. (2018, August 7). Health and safety issues from tourism activities in Bukit Tinggi City, West Sumatra . 13th IEA SEA Meeting and ICPH—SDev. http://conference.fkm.unand.ac.id/index.php/ieasea13/IEA/paper/view/622

Ohlan R., (2017). The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Business Journal, 3 (1), 9–22.

Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16 (5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

Osland, G. E., Mackoy, R., & McCormick, M. (2017). Perceptions of personal risk in tourists’ destination choices: Nature tours in Mexico. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 8 (1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/ejthr-2017-0002

Person, B., Sy, F., Holton, K., Govert, B., Liang, A., Garza, B., Gould, D., Hickson, M., McDonald, M., Meijer, C., Smith, J., Veto, L., Williams, W., & Zauderer, L. (2004). Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal CDC, 10 (2), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030750

Peterson, R. R., Harrill, R., & Dipietro, R. B. (2017). Sustainability and resilience in Caribbean tourism economies: A critical inquiry. Tourism Analysis, 22 (3), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14955605216131

Petkova, A. T., Koteski, C., Jakovlev, Z., & Mitreva, E. (2012). Sustainability and competitiveness of tourism. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44 , 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.023

Qiu, R., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994

Quevedo-Gómez, M. C., Krumeich, A., Abadía-Barrero, C. E., & Van den Borne, H. W. (2020). Social inequalities, sexual tourism and HIV in Cartagena, Colombia: An ethnographic study. BMC Public Health, 20 (1208), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09179-2

Ram, Y. (2021). Me too and tourism: A systematic review. Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1664423

Ramesh, D. (2002). The economic contribution of tourism in Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (3), 862–865.

Richter, L. K. (2003). International tourism and its global public health consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 41 (4), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503041004002

Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30 (3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001

Robinson, M. (1999). Collaboration and cultural consent: Refocusing sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7 (3–4), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589908667345

Rosselló, J., Santana-Gallego, M., & Awan, W. (2017). Infectious disease risk and international tourism demand. Health Policy and Planning, 32 (4), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw177

Ryan, C., & Kinder, R. (1996). Sex, tourism and sex tourism: Fulfilling similar needs? Tourism Management, 17 (7), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00068-4

Schwartz, K. L., & Morris, S. K. (2018). Travel and the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 20 (9), Article 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0634-9

Sheller, M. (2004). Natural hedonism: The invention of Caribbean islands as tropical playgrounds. In S. Courtman (Ed.), Beyond the blood, the beach, and the banana : New perspectives in Caribbean studies (pp. 170–185). Ian Randle.

Sönmez, S., Wiitala, J., & Apostolopoulos, Y. (2019). How complex travel, tourism, and transportation networks influence infectious disease movement in a borderless world. In D. J. Timothy (Ed.), Handbook of globalization and tourism (pp. 76–88). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786431295.00015

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. (2014). Cruise lines: Sustainability accounting standards . http://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/SV0205_Cruise_ProvisionalStandard.pdf

Telfer, D. (2002). The evolution of tourism and development theory. In R. Sharpley & D. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and development: Concepts and issues (pp. 35–78). Channel View.

The Caribbean Tourism Organization [CTO]. (2020). Caribbean sustainable tourism policy and development framework . https://caricom.org/documents/10910-cbbnsustainabletourismpolicyframework.pdf

Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2015). Strengthening community-based tourism in a new resource-based island nation: Why and how? Tourism Management, 48 , 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.12.013

Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27 , 493–504.

UNCTAD. (2020). Coronavirus will cost global tourism at least $1.2 trillion . United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://unctad.org/news/coronavirus-will-cost-global-tourism-least-12-trillion

UNWTO. (2001). Tourism highlights 2001. World Tourism Organization. Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284406845

UNWTO. (2019). United Nations World Tourism Report 2019 . Available at: https://www.eunwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152 . Accessed 24 August 2020.

Walker, L., & Page, S. J. (2004). The contribution of tourists and visitors to road traffic accidents: A preliminary analysis of trends and issues for central Scotland. Current Issues in Tourism, 7 (3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667980

Wallen, B. (2020, November 30). Why some countries are opening back up to tourism during a pandemic. National Geographic . https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/are-economics-driving-countries-to-reopen-to-tourists-coronavirus

Waterman, T. (2009). Assessing public attitudes and behavior toward tourism development in Barbados: Socio-economic and environmental implications . Central Bank of Barbados.

Wilks, J., Stephen, J., & Moore, F. (2013). Managing tourist health and safety in the new millennium . Routledge.

World Conservation Union. (1996, October 13–23). Resolutions and recommendations [Meeting]. World Conservation Congress, Montreal, Canada. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/WCC-1st-002.pdf

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2019). Economic impact reports . https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2020). 100 million jobs recovery plan: Final Proposal (G20 2020 Saudi Arabia Summit). https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2020/100%20Million%20Jobs%20Recovery%20Plan.pdf?ver=2021-02-25-183014-057

Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear.’ Tourism Management, 83, 104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104261

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hospitality & Tourism Management, College of Business, Tennessee State University, Nashville, TN, USA

David Mc. Arthur Baker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Mc. Arthur Baker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Jack C. Massey College of Business, Belmont University, Nashville, TN, USA

Colin Cannonier

Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY, USA

Monica Galloway Burke

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Baker, D.M.A. (2022). Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts. In: Cannonier, C., Galloway Burke, M. (eds) Contemporary Issues Within Caribbean Economies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Published : 09 June 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98864-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98865-4

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Caribbean comeback: The region's post-pandemic tourism rebound leads the world

Few regions saw their tourism industries suffer more during the COVID-19 pandemic than the Caribbean did. But the region is now rebounding more strongly than any other — and for some surprising reasons.

The Caribbean lost a full tenth of its collective GDP in 2020 — the worst year of the pandemic — and the big reason was that tourism, which accounts for a full 14 percent of that GDP, dropped by two-thirds.

But travel data firms like ForwardKeys now show Caribbean tourism enjoying the world’s best post-pandemic recovery. In the first two months of this year, the Caribbean’s international arrivals numbers were down only 1% compared to the same period in 2019.

By contrast, Europe’s numbers were still 25% behind — and Asia’s were 54% short.

Leading the way was the U.S. Virgin Islands, which saw a 22% arrivals increase, although the U.S. territory's pandemic recovery benefitted from U.S.-supplied vaccines and economic relief.

“These are impressive results for our region,” said Nicola Madden-Greig, president of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association.

One key reason appears to be a jump in post-pandemic travel to the Caribbean from South America — a region that usually sends its tourists to Miami. That shift is due largely to the fact that Panama is now a more active airport connection hub for South Americans to Caribbean destinations.

“ForwardKeys has uncovered the growth of Panama City as a gateway to the Caribbean for trips from South America. Miami is, on the contrary, losing its market share” for connections to the region from South America, said ForwardKeys vice president Olivier Ponti.

- Faculty Voices Podcast

- Current Issue

- Spotlight: Costa Rica

- Perspectives in Times of Change

- Past Issues

- Student Views

- Student ReViews

- Book Reviews

Select Page

- Focus on Cuba and the Caribbean

Caribbean Tourism and Development

by Yorghos Apostolopoulos and Sevil Sönmez | Dec 18, 2002

A Havana street scene. Photo by Andrew Klein.

Mass charter tourism is the cornerstone of development plans in the Caribbean. Unparalleled tourism investment in the post-World War II era has boosted a tourist influx of unprecedented dimensions, the world’s largest peacetime population movement, especially in developing insular regions. The heavy influx of tourists has contributed to significant economic gains in Caribbean nations. However, it has simultaneously inflicted a plethora of long-term adverse consequences, including the emergence and diffusion of infectious diseases. Paradoxically, while the sustainable development of the Caribbean requires the control of infections and diseases, travel and tourism actually produce the facilitating conditions for their very emergence.

Tourism, the dominant economic activity of the Caribbean islands, reaches higher than 90% of Gross Domestic Product in many islands. At the same time, this vital source of income has also been identified as a major threat to the region’s sociocultural, ecological, and public health sustainability. These include spatial and socioeconomic polarization, uneven development, ecological degradation, domination of regional political economies, management repatriation, rising alienation among locals, and structural under-development. Such negative externalities of tourism have eclipsed the potential for equitable social, sectoral, and regional benefits, especially considering that mass tourism was expected to demonstrate the greatest positive impact. Further, this unprecedented growth has resulted in a surplus of accommodations and its subsequent consequences, inflationary pressures causing dramatic rises in the cost of living, labor and other resource shortages, and a failure to integrate tourism with other sectors.

The conventional mass tourism model must undergo a significant overhaul to avoid undermining local communities, ecological and social systems. This means encouraging different types of tourists and tourism, spreading tourism over more diverse destinations, and thinking about products in markets, in short, profound structural changes in the tourist industry. These modifications must include interregional differentiation, diverse regional tourism production, and maximized economic benefits in both the informal and formal sectors over an entire region. All this can be accomplished by initiating effective interlinkages between tourism and other economic sectors, by assuring equity and encouraging local involvement, by incorporating environmental considerations into policy making and tourist product development, and by assuring continuity and adjustability of the region’s tourism development within its wider environment. Further, considering the tourism industry’s vulnerability to uncontrolled internal and external shocks (i.e., recession, natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, epidemic disease), the welfare of the littoral Caribbean may be undermined and ultimately constrained by neglect of the critical importance of social and geographic ecology.

HEALTH REPERCUSSIONS OF CARIBBEAN TOURISM

While microbial adaptation and change most often account for the origin of diseases, international travel has been linked with an explosion of disease propagation in several geographic regions. When people travel, not only do they carry their genetic makeup, disease pathogens and vectors, and accumulated immunologic experience, but they also transport their capacity to introduce diseases into new regions. Like other exchangeable goods, the diffusion of disease through traveling human populations traces the structure of social networks, as various diseases travel along different structural routes.

The Caribbean already suffers from problems associated with underdevelopment and endemic and climate risks. However, the annual influx of millions of mass tourists to the Caribbean constitutes an added pathway for the diffusion of infections and diseases. It also sets the stage for intermingling diverse genetic pools and cultures. The public health repercussions affect the host population, as well as the traveler, in ways previously unknown and unanticipated. The tourist brings these public health repercussions back home, and both ecosystems receive their impact. The global leisure revolution, ongoing improvements in transport media, and movement between diverse climatic zones (exemplified by global warming and climate change) have exacerbated the vulnerability of travelers to infectious diseases. Beyond the illnesses induced by travel itself, the exposure to unfamiliar infectious agents and demonstration of risky behaviors heightened by the vacation setting and culture, have the potential to cause enormous health strains on the parties involved.

Travel health risks in the Caribbean, ranging from malaria and dengue fever to HBV and dysentery, differ by types of travel. However, mass tourists are the travelers most at risk for infection. Furthermore, the magnitude of health consequences of mass tourism largely depends upon the volume and scope of tourists, as well as health determinants related to the process of travel. The tourist influx bridging disparate population health determinants often crosses gaps in socioeconomic development and public health practices with analogous consequences.

As is the case in most littoral areas, risky behavioral patterns involving substance misuse and casual/unprotected sexual encounters constitute a prevalent hazard in the Caribbean islands particularly due to the pervasiveness of “sun, sea, sand, and sex” tourists. Moreover, the tourist-based commercial sex industry, fueled by the eagerness of certain travelers to seek out commercial sex opportunities while on a Caribbean vacation provides prostitutes with ample opportunities to give sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) to travelers in the absence of state control and regulation. Further, similarly risky encounters occur between “beach boys” and white foreign women, between locals and “exotic” visitors, and between pedophiles and victims of child sex tourism. In the Caribbean, as in many other developing tourist regions, informal sector tourism is inseparable from the sexual exploitation of women and children. Sex tourism is based on networks that provide services such as tourist guides, prostitutes, brothels, and massage parlors and often serve foreign sex tourists as well as local customers. Minors in particular are attracted to working in sex tourism by the lure of foreign tourists’ wealth and consumerism. Sex tourism, homophobia, and poverty have been blamed for the AIDS increase in the Caribbean, which has the second highest rate of HIV infection after Africa. Surprisingly, the Caribbean along with Latin America continues to be perceived as an attractive destination by sex tourists.

Preconceived images of “exotic” local women have fueled the idea that they are full of sexual energy or that they only think about sex. These images are often promoted as part of the amenities of a tourist holiday package by some islands, such as the Dominican Republic. On others, such as Haiti, sex between adult male tourists from the U.S. and local children has remained a part of the informal commercial sex industry for many years. Of course, while tourism is not the cause of minors’ sexual exploitation, it does provide easy access to vulnerable children. Therefore, the acute importance of regulation and health surveillance of the commercial sex industry is self-evident, particularly as it intersects with travelers.

HEALTH POLICY FOR A GLOBALIZED INFLUX

The globalization process has dramatically transformed global tourist patterns. As there are clear indications that human mobility will further intensify over the coming years, regardless of the setbacks experienced by the tourism industry resulting from the September 11 terrorist attack in the U.S., there are immense public health ramifications. Tourist health is practically treated as a hidden dimension of tourism and consequently neglected. Yet, both tourists in the Caribbean and host populations are increasingly exposed to new health problems as the circulation of pathogens and vectors increases due to intersecting epidemiological and sociocultural boundaries. Discrepancies in the level of knowledge and types of beliefs, attitudes toward diseases and health, and expectations for and access to health services or information are likely to exist between travelers’ home communities and the destinations they visit. Assessing and monitoring factors that affect health and health services for international tourists are crucial for anticipating and proposing changes and adaptations to tourists’ health needs. A clear understanding of the related causes and risk factors is critical for targeting adapted preventive interventions. The growing awareness of the dangers of HIV/AIDS and other STIs make this even more imperative, especially since such serious health risks can create irreversible problems for the Caribbean’s predominantly “4S” tourist market.

The health risks of travelers are related not solely to the destination and direction of travel but also to the movements of tourists across epidemiological, behavioral, and geographic boundaries. The multi-directionality of tourist flows in the Caribbean and their demographic composition can essentially determine the health characteristics of populations. Since tourism is of such importance to the Caribbean, the promotion of travel health represents a crucial strategy because subsequent public policies, if properly initiated, could make significant contributions to the maintenance and growth of international economies. While travel health promotion may have the correct intentions, its shortcomings are often due to unplanned and uncoordinated activities within the amorphous, acephalous, and fragmented tourist industry, to the narrow focus of much contemporary medical education, to widespread ignorance of medical (disease) geography, and to the associated risks of disease importation and spread from tourist migration.

Because of increasing global tourism and emerging and re-emerging infections, the World Health Organization and World Tourism Organization have been urged to cooperate on a strategic initiative to provide guidelines for future action. The global public health ramifications of tourism can only be mitigated by the synergistic efforts of these international organizations. The emphasis of the initiative rests on the importance of working with primary stakeholders involved in and influenced by global tourism patterns. The “healthy travel and tourism” campaign has resulted. The campaign aims to define constructive action priorities to avoid health problems, to promote health among both travelers and host communities, and to establish healthy tourism networks among private sector representatives (such as tour operators and travel agencies) and host country authorities. Travel health promotion as well as mitigation planning, ongoing disease prevention, hazard mapping and surveillance, and risk assessment bolstered by sociomedical research are critical for a sustainable tourism sector in the Caribbean.

Winter 2002 , Volume I, Number 2

Yorghos Apostolopoulos is a Research Associate Professor of Sociology and Sevil Sönmez is an Associate Professor of Tourism Management, both at Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. Their work delves into development, health, population/tourism, and the epidemiology of migration.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Tourism

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Recreating Chican@ Enclaves

Centrally located between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is a hundred-mile long by seventy-mile wide intermountain basin known as the San Luis Valley. Surrounded on the east …

Tourist Photography’s Fictional Conquest

Recently, while walking across the Harvard campus, I was stopped by two tourists with a camera. They asked me if I would take a picture of them beside the words “HARVARD LAW SCHOOL,” …

Harvard University | Privacy | Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2020 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

Admin Login

Tourism in the Caribbean – The Way Forward to Recovery

On Thursday, 2nd July The Caribbean Council hosted the latest of its LIVECaribbean webinar series on “Tourism in the Caribbean – The Way Forward to Recovery”. We were privileged to have three fantastic tourism speakers: Vincent Vanderpool Wallace – Principal Partner at The Bedford Baker Group; David Weatherson – Business Development Manager at Sun Group; and Patricia Affonso-Dass – Group General Manager of Ocean Hotels and President of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association, who each shared with us their experiences and lessons learned during the COVID-19 crisis. Some of those insights are set out below.

What is clear is that tourism will be different after COVID-19 and, while the sector has been impacted on an unprecedented scale, there are valuable lessons to be learned and positive changes to be implemented.

COVID-19: Impact

The magnitude of the COVID-19 crisis – in terms of its economic impact – has been greater than any known shock to the Caribbean. The global tourism industry has taken a “nuclear hit”, the airline industry is tarmacked, and thousands of businesses are shuttered as closed borders are only now progressively reopening in the region.

Between March and May 2020, estimates show that global lockdown measures have resulted in a US$6bn loss in tourism earnings and a US$2bn loss in tax revenue from tourism-related activity in the Caribbean. One million temporary job losses related to tourism alone have also been reported. According to the UN WTO, tourism arrivals to the region had declined by 22% in March and forecasts estimate a decline of up to 78% by the end of the 2020.

Much remains completely out of the control of the region, in which most governments took swift and decisive action to contain the spread of COVID-19 and to flatten the curve. The Caribbean’s response to supress the virus has, for the most part, been a success with some islands managing to keep the infection rate at zero for weeks. This has not been the case for many of the region’s key source markets, where COVID-19 continues to spread. The region will not be able to open its borders to source markets that do not meet health pre-requisites for travel.

The Caribbean therefore remains dependent on scientific developments to monitor, treat and prevent the spread of COVID-19. The absence of a vaccine, and a lack of rapid and widely available tests place serious constraints on the Caribbean’s process of reopening to tourism.

How can the region move forward? Many lessons are being learned by the private and the public sector.

Tourism permeates nearly every aspect of the region’s economies

The sector has proven a crucial source of employment, particularly for the islands in the region, as the only sector able to absorb a wide set of skills. It has proven a pivotal generator of wealth and income, as well as tax revenue both through direct and indirect taxes. It is also a sector through which economic diversification can be achieved, by providing opportunities for destinations to test the receptiveness of potential consumers of, for example, cultural or financial products.

Given the importance of tourism, governments will need to collaborate with the private sector and enable them to pave a path forward. Of note, governments are being encouraged to rethink ways that the sector is taxed, including taxes on air travel, in order to create incentives and remove obstacles to tourism.

Continued regional collaboration on protocols and guidelines is needed

In preparation for economic reopening, CARPHA, the Caribbean Tourism Organisation (CTO), the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and the Jamaica-based Global Resiliency and Crisis Management Centre, have collaborated to establish guidelines, protocols and provide training with the aim of building consumer confidence, and ensuring the safety of the region’s employees. National tourism associations have supported local and regional efforts with data collection and dissemination in order to inform a collaborative and coordinated approach.

This downtime has also given the sector room to reflect on ways that the Caribbean can be made more commercially resilient. Post-COVID-19 travel arrangements remain an unknown, but as the region moves forward to recovery, it is evident that contractual terms with supplier partners will need to be adapted so that the sector is not left financially exposed to shocks. Payment terms and indemnity clauses are being reviewed to that end.

Commercial strategies will need to adapt

Recovery is far from straight forward as the region relies on how well its source markets are able to weather the storm. Hotels, tour operators and airlines will likely try to appeal to a younger, less at-risk demographic, but will have to adapt their service offering to account for pressures on disposable incomes of potential travellers, and the possibility of a global recession.

The Caribbean is reliant on the airline industry to get tourists to the region. Recovery speed will likely be impacted by reduced service, increased airfare, and the airline industry’s reliance on already stretched government aid to remain afloat. A more coordinated approach to making travel to and across the region more efficient and less costly will be needed to promote regional tourism.

Business models will need to evolve, staffing needs will change, hospitality delivery, aesthetic and style will also need to adapt in keeping with health and safety requirements.

Technology and data-literacy are now paramount

The crisis has also revealed the need of a more prevalent use of data and analytics. COVID-19 containment measures and the phasing out of lockdowns across the region have been guided by scientific data. The tourism sector is hoping that systematic data-driven decision making will now transfer to government policy and commercial planning in the tourism industry.

There has been an unprecedented level of regional collaboration thanks to technology. Now tourism stakeholders across the Caribbean are collaborating on a variety issue areas without having to spend time and money on travelling. Quality Wi-Fi has therefore become a mandatory piece of infrastructure.

Missed our webinar? Full recording now available, please contact [email protected] to learn more .

Proud Supporters of

Follow Us on Social Media

- January 9, 2023

Tourism in the Caribbean

The Caribbean has a very diverse culture as a result of the region’s rich history. Countries are home to many historical man-made attractions such as forts and colonial era structures, as well as many natural attractions, primarily pristine beaches all complemented by a warm tropical climate. It is no surprise that many countries in the region have sought to capitalize on these features by promoting the tourism industry, attracting visitors from around the globe. The tourism industry, primarily international tourism (by air and cruise), has become a vital part of Caribbean economies with many being heavily dependent on the sector not only for driving economic activity but also to generate much needed foreign exchange. Inter-regional tourism, while present, does not contribute on the same scale because of deficiencies in air connectivity in combination with a prohibitive relative ticket cost. Limited number of flights along with high taxes, fees, and charges (TFCs) on regional flights make it cheaper for travelers to fly outside of the region.

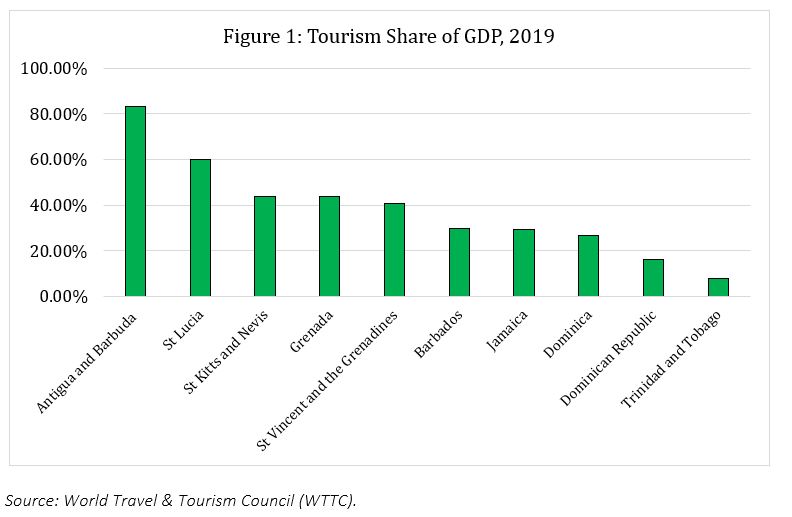

The World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) notes that eight out of the ten countries most dependent on tourism are from the Caribbean. Tourism contributes approximately 13.9% of GDP for the entire Caribbean, the highest share of any region in the world. The contribution of travel and tourism towards GDP for Caribbean countries is shown in Figure 1.

The reliance on the tourism sector has made the economies of the Caribbean very vulnerable to shocks in the global economy as well as the environment. The tourism sector is highly dependent on international conditions as was proven with the COVID-19 pandemic. Major source markets for the region are the United States of America (US), United Kingdom (UK), Canada, and France, making up 70% of all travelers entering the region in 2019 according to the WTTC. In the height of the pandemic, strict lockdown measures were introduced in these major markets, driving Caribbean economies to a virtual standstill.

Further to this, the Caribbean is also highly susceptible to natural disasters. According to the OECD, the Caribbean is the second most environmental hazard-prone region in the world, with natural disasters and climate change causing major economic and infrastructural damages. Recent examples of natural disasters that have struck the region are Hurricane Dorian in 2019 that made landfall in The Bahamas, causing roughly USD3.4 billion (over 25% of GDP) in damages; Hurricane Maria in 2017 which ravaged Dominica, destroying roughly 90% of the island’s infrastructure and costing an estimated USD1.3 billion (226% of GDP).

Tourism Industry Recovery

The tourism industry came to a standstill in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with lockdown measures and strict travel restrictions being imposed by governments to curb the spread of the virus. International travel was generally restricted to only what was absolutely necessary for 2020 and only eased slightly in the Q1 2021. It was not until the Q2 2021 that restrictions began to gradually ease as vaccines were more readily available around the world and the number of cases began to fall. The easing of restrictions saw the return of tourists as air travel resumed, even though with strict testing and vaccination requirements. While the cruise industry was essentially closed off for most of the pandemic, nearing the end of 2021 and throughout 2022, the industry reopened, though, its performance remains below pre-pandemic levels.

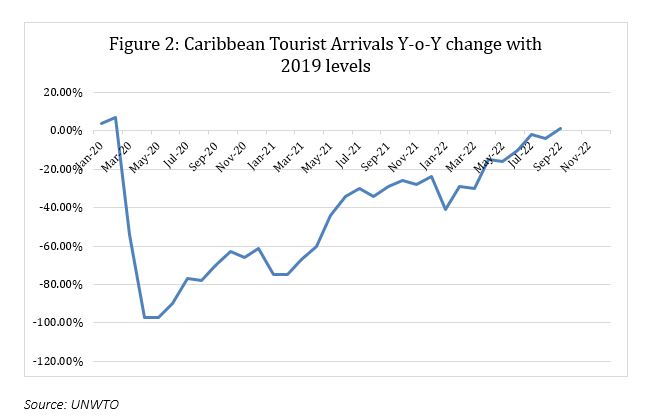

Data from the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) shows that as of September 2022, global tourism has recovered significantly, only 27% below 2019 levels. Recovery in the Caribbean has been much more robust, with the region outpacing most of the world. UNWTO data indicates that monthly tourist arrivals for September 2022 were the same as 2019, though total arrivals for the year is 18% less. The recovery path for tourism in the Caribbean region is shown in Figure 2.

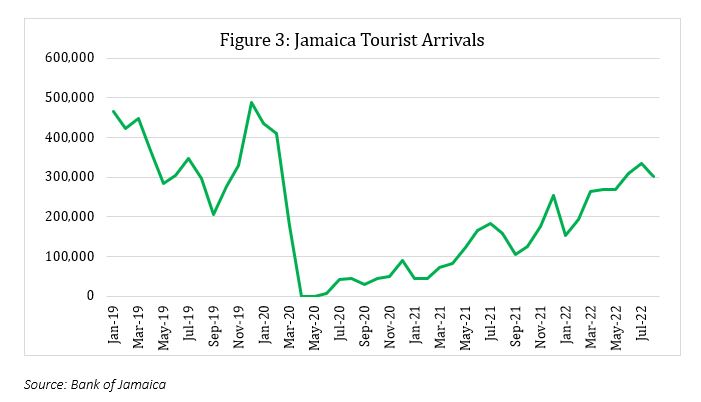

In the Caribbean, the recovery of the tourism industry varied greatly depending on the restrictions and travel policies in place in different countries. Countries such as Jamaica were able to recover more quickly than others in the region largely due to restrictions being eased at a much quicker pace than the rest of the region. Jamaica was amongst the first in the Caribbean to ease and subsequently remove travel restrictions for international travelers; in March 2022 travel authorization requirements were removed for entry into Jamaica, making the country open to all visitors. Given the significant contribution of tourism towards Jamaica’s GDP (29.1% of GDP in 2019), growth in the Jamaican economy began to recover, primarily driven by the tourism industry. Further, in April 2022, all testing requirements were removed for travelers entering Jamaica, which allowed for an improvement in processing speeds for travelers. As a result, the recovery of the tourism sector in Jamaica accelerated, with the months following, almost reaching 2019 levels. Figure 3 shows the total amount of tourist arrivals in Jamaica from 2019.

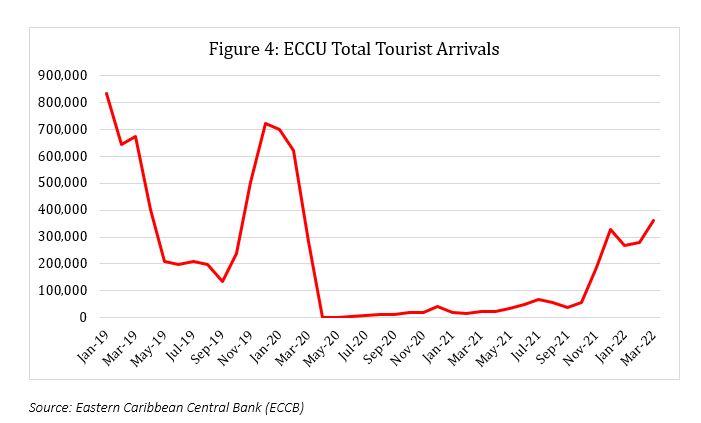

In the height of the pandemic, travel into the Eastern Caribbean ground to a stop. Data from the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) shows that for the period April 2020 – December 2020 total travelers entering the Eastern Caribbean was a mere 1,887, this is compared to 2.8 million for the same period in 2019. Latest data from the ECCB (March 2022) shows that while tourist arrivals have recovered, levels were still well below where it was pre-pandemic. Figure 4 shows total arrivals for the entire Eastern Caribbean.

On a country level, the rate of recovery has varied due to restrictions being eased at different periods from country to country. Some of the earliest countries to ease restrictions were St Lucia and Grenada, with the former easing restrictions in March 2022, and the latter removing all restrictions in April 2022. Countries such as St Vincent and the Grenadines have only recently removed pre-testing requirements for fully vaccinated travelers as of August 2022, whereas Antigua and Barbuda, and St Kitts and Nevis have fully removed all entry requirements that were in place.

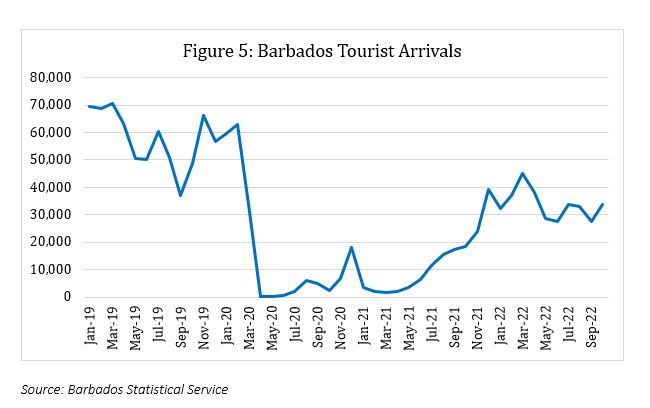

Barbados’s economy depends on the tourism industry for a significant chunk of activity (29.5% of GDP in 2019). It is of no surprise that with the stagnation of the industry, the Barbadian economy suffered a severe contraction. With regards to COVID-19 restrictions, Barbados has been relatively conservative, keeping some travel restrictions in place until September 2022, with a gradual easing at key periods to aid in recovery efforts. The easing of restrictions and the subsequent recovery in tourism has been the main driver of growth for the past six quarters in the Barbados economy. Tourism arrivals do however remain well below pre-pandemic, reaching 71% of 2019 levels in September 2022. Figure 5 shows total tourist arrivals into Barbados.

The tourism industry in the Caribbean is expected to sustain its recovery, however, at a slower pace. Growth in the tourism sector for 2023 is projected by WTTC to slow further to 11.1% in the Caribbean region, much lower than 2021 and 2022 which saw growth of 36.6% and 27.2% respectively. Pent up demand, easing of COVID protocols by countries, and a forecasted improvement in the cruise industry will drive tourism growth in 2023 for the Caribbean. Downside risks to the industry include persistently rising prices, the threat of prolonged recessions in key tourist markets, as well as fluctuations in the currency market.

Two of the most significant source markets, the US and UK, are projected to slow further in 2023, with GDP forecasted by the IMF to grow at 1% and 0.32% respectively. This projected low growth comes after a less than stellar performance throughout 2022. The US economy contracted by 1.6% and 0.6% for Q1 and Q2 2022 before recording growth of 3.2% in Q3 2022, while in the UK, growth has been moderating sharply, with current forecasts showing persistent economic contractions until Q4 2023.

For the Eastern Caribbean, travelers are primarily from the US (43.4% of all travelers in 2019) with a notable contribution from the UK (16.6% in 2019). The slowdown of the US and UK economies will likely impact tourism activity as a result. Given the significance of US in the Eastern Caribbean, fluctuations in the US dollar (USD) will greatly affect the tourism demand. The Eastern Caribbean Dollar (XCD) is fixed to the USD at a rate of XCD2.7 to USD1; given the fixed exchange rate, tourist demand would fall if there is a strengthening of the USD as the relative cost to tourists would be higher. The USD is currently forecasted to strengthen in 2023 as the rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve continue to make the dollar an attractive asset, serving as a downside risk to tourism in the Eastern Caribbean. Tourism growth will vary slightly among countries within the region; St Vincent and the Grenadines, St Kitts and Nevis, as well as Antigua and Barbuda are expected to post the highest growth, largely in part to their recent removal of restrictions for travelers entering the country.

Jamaican tourist arrivals are forecasted to remain along its current trajectory, with the total number of arrivals improving with the return of the cruise industry. Jamaica operates a managed floating exchange rate regime, with the Bank of Jamaica gradually depreciating the value of the Jamaican dollar (JMD) in recent years to boost competitiveness of exports. This gradual depreciation of the JMD may be beneficial and can potentially improve tourism demand. Tourism is forecasted to return to pre-pandemic levels in Jamaica by mid-2023.

Barbados’s key tourist markets are the US and the UK, making up roughly 32% and 33% of all tourist arrivals in 2019. The projected slowdown of these economies in 2023 will negatively affect Barbados’ tourism sector. Similar to the Eastern Caribbean, Barbados operates a fixed exchange rate regime, at a rate of BBD2 to USD1. The forecasted strengthening of the USD will reduce the relative competitiveness of tourism in Barbados for tourists.

Notwithstanding the headwinds, the tourism industry is expected to continue along the path of recovery, supported by the complete removal of all pandemic restrictions as well as projected improvements in the cruise industry.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.

SMS Banking Commands

First Citizens SMS Banking allows you to use your cell phone to access eligible accounts using SMS:

- Check your account balances (for eligible accounts)

- View a list of your most recent account activity

- Transfer funds between eligible accounts

To use First Citizens SMS Banking you need the following:

- To be registered for First Citizens Online Banking

- To have a verified mobile device

- To have a mobile device that supports SMS or Text Messaging

What are Commands and how do I use them?

Commands are the SMS you send from your mobile device to First Citizens to request your account information or transfer money between your eligible accounts. After you have verified your mobile phone number, send a SMS to the First Citizens Mobile Text short code 34778 (FIRST) using one of the commands.Each of these quick codes will request an SMS with the information shown below :

Sending Commands:

Using SMS Banking is as simple as sending a short command via SMS to the First Citizens shortcode 34778 (FIRST).

- Type “ Bal Sav1 ” as a SMS. The format to be used is Bal (space) account_nickname

- Send to shortcode 34778 (FIRST)

- You will receive a SMS which will state the available balance on the account you nicknamed as Sav1.

When you send First Citizens a SMS, make sure you send it to the First Citizens SMS Banking short code 34778 (FIRST) . You may be able to store this number in your mobile contacts or address book just like a regular phone number.

Below are Five important tips to ensure that your Online Banking experience is optimised by protecting your PC from fraudulent attempts. Read on to find out more.

- Ensure that you install the latest security patches and updates to correct weaknesses in your system – it only takes one point of entry for hacking to occur

- Install the latest Ant-Virus software to safeguard against viruses, in addition to regular virus sweeps of your system

- Protect your system and its contents, by utilizing a personal firewall which minimizes outside attacks by unauthorized traffic.

- Choose a password which no one else can think of, but is easy to remember. By using letters, numbers and symbols this reduces the likelihood that your password can be guessed.

- Run anti-spyware programs regularly to prohibit the acquisition of personal information, for example, passwords, telephone numbers, credit card numbers and identification card numbers

Carrying out these simple steps can offer you some protection against the electronic threats out there. The likelihood of becoming susceptible to these threats is still there, as these measures are designed to minimize these threats.

Caribbean Tourism Organisation (CTO)

The Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) with headquarters in Barbados, is the Caribbean’s tourism development agency comprising membership of 24 countries and territories including Dutch, English, French and Spanish, as well as a myriad of private sector allied members.

The primary objective of the Caribbean Tourism Organization is to provide to and through its members the services and information necessary for the development of sustainable tourism for the economic and social benefit of the Caribbean people by:

providing an instrument for close collaboration in tourism among the various territories, countries and other interests concerned;

developing and promoting regional travel and tourism programs to and within the Caribbean;

providing members with opportunities to market their products more effectively to both the Caribbean and the international tourism marketplaces;

assisting member countries, particularly the smaller member countries with minimal promotional budgets, to maximize their marketing impact through the collective CTO forum;

carrying out advertising, promotions, publicity and information services calculated to focus the attention of the public upon the Caribbean as one of the world’s outstanding tourist destinations;

providing a liaison for tourism matters between member countries;

providing a sound body of knowledge on tourism through data collection, collation and research;

creating processes and systems for disseminating and sharing tourism information;

providing advice, technical assistance and consultancy services with respect to tourism;

providing training and education for Caribbean nationals and for international travel agents;

seeking to maximize the contribution of tourism to the economic development of member countries and the Caribbean through programs likely to increase foreign exchange earnings, increase employment, strengthen linkages between tourism and other economic sector like manufacturing and agriculture, and to reduce leakages from Caribbean economies;

encouraging coordination with respect to research and planning and the efficient allocation of local, regional and international resources at both government and non-governmental levels in tourism development;

researching and identifying the ecological effects of tourism with a view to recommending and /or initiating action aimed at minimizing the negative and enhancing the positive effects;

promoting the consciousness of the need to preserve both the natural and man-made beauty of the Caribbean environment and demonstrating its direct relationship to the development of an attractive tourism product;

developing a tourism product which is essentially Caribbean and which, through maximizing economic benefits, has minimal adverse social and psychological effects on the integrity of Caribbean peoples

Vision and Purpose

The CTO’s vision is to position the Caribbean as the most desirable, year-round, warm weather destination and our purpose is Leading Sustainable Tourism – One Sea, One Voice, One Caribbean.

Visit Website

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Cruise industry in the Caribbean – statistics & facts

Main cruise ports in the caribbean, economic impact of tourism in the region, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Cruise ship calls in Mexico 2013-2022

Mexico: expenditure of international cruise excursionists per capita 2016-2023

Cruise ship calls in Central America 2018-2023, by coastline

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Total tourism contribution to GDP in Caribbean countries 2022

Cruise passenger traffic in Mexico 2022, by port

Number of global ocean cruise passengers 2019-2022, by source market

Related topics

Recommended.

- Travel and tourism in Mexico

- Medical tourism in Latin America

- Cruise industry worldwide

- Cruise shipbuilding industry worldwide

- Water transportation industry

Recommended statistics

Global overview.

- Premium Statistic Global cruise fleet deployment 2023, by region

- Premium Statistic Number of global ocean cruise passengers 2019-2022, by source market

- Premium Statistic Main global cruise destinations 2019-2023, by number of passengers

- Basic Statistic Longest cruise ships worldwide 2023, by length

Global cruise fleet deployment 2023, by region

Distribution of the global cruise fleet worldwide in 2023, by region

Number of ocean cruise passengers worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by source region (in 1,000s)

Main global cruise destinations 2019-2023, by number of passengers

Leading ocean cruise destinations worldwide from 2019 to 2023, by number of passengers (in 1,000s)

Longest cruise ships worldwide 2023, by length

Largest cruise ships worldwide as of February 2023, by length (in meters)

Cruise traffic

- Premium Statistic Cruises in the Caribbean 2019-2023

- Premium Statistic Cruise ship calls in Central American countries 2023, by coastline

- Premium Statistic Cruise ship calls in Central America 2018-2023, by coastline

- Premium Statistic Central America: main Caribbean ports by cruise passenger traffic 2023

- Premium Statistic Cruise ship calls in Central American Caribbean ports 2023

Cruises in the Caribbean 2019-2023

Number of cruise vessels in the Caribbean in 2019 and 2023

Cruise ship calls in Central American countries 2023, by coastline

Number of cruise vessels calling at ports in Central America in 2023, by country and coastline

Number of cruise vessels calling at ports in Central America from 2018 to 2023, by coastline

Central America: main Caribbean ports by cruise passenger traffic 2023

Busiest Caribbean ports based on number of cruise passenger traffic in Central America in 2023

Cruise ship calls in Central American Caribbean ports 2023

Number of cruise vessels calling in the Central American Caribbean coastline in 2023, by port

Passenger arrivals

- Premium Statistic Visitor arrivals by cruise in Caribbean destinations 2021

- Premium Statistic Cruise passenger traffic in Mexico 2022, by port

- Premium Statistic Cruise passenger traffic at the port of Cozumel 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Cruise tourism volume at Old San Juan 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Busiest Jamaican cruise ports 2018-2021, by number of visitor arrivals

- Premium Statistic Cruise visitor arrivals in Turks & Caicos 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Yacht and cruise ship passengers in Grenada 2010-2022

Visitor arrivals by cruise in Caribbean destinations 2021

Number of cruise passenger arrivals in the Caribbean in 2021, by destination (in 1,000s)

Number of cruise passengers in Mexico in 2022, by port (in 1,000s)

Cruise passenger traffic at the port of Cozumel 2013-2022

Number of cruise passengers at Cozumel port in Mexico from 2013 to 2022 (in millions)

Cruise tourism volume at Old San Juan 2010-2022

Number of cruise passengers at the port of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Busiest Jamaican cruise ports 2018-2021, by number of visitor arrivals

Leading cruise ports in Jamaica from 2018 to 2021, by number of passenger arrivals (in 1,000s)

Cruise visitor arrivals in Turks & Caicos 2013-2022

Number of cruise passenger arrivals in the Turks and Caicos Islands from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Yacht and cruise ship passengers in Grenada 2010-2022

Number of tourists who arrived by sea in Grenada from 2010 to 2022, by type of transport (in 1,000s)

Origin of travelers

- Premium Statistic North American cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic European cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic South American cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Asian cruise travelers in Caribbean and South America 2019-2022

North American cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

Number of North American cruise passengers in the Caribbean from 2019 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

European cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

Number of European cruise passengers in the Caribbean from 2019 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

South American cruise travelers in Caribbean 2019-2022

Number of South American cruise passengers in the Caribbean from 2019 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Asian cruise travelers in Caribbean and South America 2019-2022

Number of Asian cruise passengers in the Caribbean and South America from 2019 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Expenditures

- Premium Statistic Cheapest U.S. cruise lines in the Caribbean 2024

- Premium Statistic Average cruise traveler spend per person in the Dominican Republic 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Mexico: expenditure of international cruise excursionists per capita 2016-2023

- Basic Statistic Cruise tourists' spending in Costa Rica 2010-2022

Cheapest U.S. cruise lines in the Caribbean 2024

Most affordable cruise trips from the United States in the Caribbean in January 2024 (in U.S. dollars), by line

Average cruise traveler spend per person in the Dominican Republic 2012-2022

Average per capita expenditure of cruise passengers in the Dominican Republic from 2012 to 2022 (in U.S. dollars)

Average expenditure of international same-day visitors who traveled by cruise to Mexico from 2016 to 2023 (in U.S. dollars)

Cruise tourists' spending in Costa Rica 2010-2022

Expenditure by cruise passengers in Costa Rica from 2010 to 2022 (in million U.S. dollars)

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

- Industry Opportunities

- Niche Tourism

Join the Caribbean’s Growing Niche Tourism Industry

Invest in the Caribbean's long-established tourism industry attracts 30+ million visitors annually. Beautiful beaches, incredible food, outdoor recreation, and a cultural affinity with the U.S., UK, and Europe have made the Caribbean a top destination for families, honeymooners, world travelers, and retirees.

Recently the market has expanded from traditional vacation tourism to include niche tourism sectors such as medical tourism, ecotourism, agrotourism, adventure tourism, and wellness tourism. These represent an incredible opportunity for investors looking to expand operations to the Caribbean or build something from the ground up.

Invest in the Caribbean. It's the Right Place to Invest!

Our region offers European educational and infrastructure standards combined with Caribbean hospitality and beautiful weather. CAIPA Secretariat members are ready to assist niche tourism investors in finding their next opportunity. Invest in the Caribbean today!

Now Viewing: All

Sorted by: Name

By the Numbers

(World Bank, 2020)

Caribbean Tourism Industry Remains Hopeful of Gradual Rebound

BRIDGETOWN, Barbados (13 Jan., 2022) – The Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) remains positive about the continued rebound of the tourism industry even in the face of the uncertainty caused by the ongoing pandemic.

Over the past eighteen months, Caribbean destinations, without exception, have shown their resilience in creating strategies for recovery, incorporating frequently updated travel protocols, and collaborations with regional and international partners in the areas of health and economic support and development. Recovery in each instance, has taken place while ensuring the health and safety of residents and visitors alike.

The year 2021 has given us an indication that there is light at the end of what has been a long tunnel which began in March 2020. By mid-2021, we saw a turnaround in tourism activity, with the Caribbean exceeding the global average for stayover arrival growth and tourism’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP). During the third quarter of 2021, there were 5.4 million tourist arrivals to the region, almost three times the arrivals for the same period in 2020, but still 23.3 per cent below 2019 levels. Preliminary reports suggest that this progress continued through to the end of the last quarter. Consequently, it is estimated that tourist arrivals for 2021 will exceed 2020 levels by 60 to 70 per cent.

As we begin 2022, once again grappling with the effects of a new variant which is also affecting international travel adversely, we are heartened by the recovery experiences and the lessons learnt in 2021.

These experiences and lessons have taught us that travel and hospitality can co-exist with the pandemic affecting both our destinations and markets. While the results to date have not indicated a return to 2019 levels, the exceptional results recorded in the summer to year-end period of 2021 show that a scaled or gradual rebound is likely and very possible by the end of 2022.

Recovery strategies, continuously being adapted to existing circumstances, based on continued partnerships and collaboration, advocating for safe and healthy visitor experiences and prioritising the health of residents, have proven to be the formula for recovery of the sector.

The year 2022 is being observed as the year of wellness in the Caribbean, with a focus on renewal. Given the Caribbean’s unique diversity, destination by destination, visitors to our shores will discover endless options to be rejuvenated in the region. Similarly, we encourage Caribbean nationals to explore and rediscover the diversity within their own destinations and those around them.

Even as we work on our short-term strategies for recovery of the sector, we urge longer term approaches to promote sectoral sustainability. Building on our 2021 World Tourism Day message, we encourage moving towards social inclusion and creating smart destinations based on smart businesses as key planks which will lead to sustainability. Our human resources, which are our key assets, are critical to the success of the sector. During 2022, the CTO hopes to build on a regional study of human resources to maintain the excellence of our hospitality.

Clearly there is a demand for the region’s tourism product, as shown by our ability to outpace the global growth average for arrivals. It is our responsibility to ensure that we continue to position the region to meet this demand in new and refreshed ways.

Let us continue to rebuild together.

Posted in: 2022 News , Blog

Let's Build Tourism Leaders

Donate to the CTO Scholarship Foundation.

Privacy Overview

Travel | Cruise demand leaves pandemic in rearview with…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Daily e-Edition

Evening e-Edition

- Entertainment

- Theater and Arts

- Things to Do

- Restaurants, Food & Drink

Things To Do

Subscriber only, travel | cruise demand leaves pandemic in rearview with record passengers, more construction on tap.

MIAMI BEACH — The COVID pandemic drove the cruise industry to a standstill, but numbers released Tuesday signal the years of comeback are officially over with more expansion on tap.

More than 31.7 million passengers took cruises worldwide in 2023, said Kelly Craighead, Cruise Line International Association president and CEO, speaking at the annual Seatrade Cruise Global conference at Miami Beach Convention Center.

CLIA is the lobbying group for member cruise lines, including Royal Caribbean, Disney Cruise Line, Carnival, Norwegian, MSC and most other major brands.

The pandemic shut down sailing from March 2020 with only a small number of ships coming back online 18 months later in summer 2021. Cruise lines didn’t return to full strength until partially through 2022, so it wasn’t until a full year of sailing in 2023 that the industry could get a real handle on just what the demand had grown to as people returned to vacation travel.

“We are an industry that’s resilient and thriving all around the world, breaking records in ways we might never have imagined,” she said.

The 2023 total is 2 million more than the industry had in 2019. CLIA projects 34.1 million in 2024 growing to 34.6 million in 2025. It’s still a miniscule chunk of the overall travel pie of more than 1.3 billion, but cruise’s share is growing.

She noted that surveys of travelers who would consider a cruise for a vacation are at an all-time high, noting that 82% who had previously cruised said they would cruise again, but more importantly, among those who had never sailed, 71% would consider it.

The youngest generations — Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z — are the biggest drivers.