National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Robin Lee Graham, pictured sailing in 1968 in Durban, South Africa, circumnavigated the world solo and wrote about it for National Geographic. His memoir Dove details his epic journey.

Set sail with these 10 books about epic ocean voyages

From solo trips around the world to family sojourns in the Pacific Northwest, these tales of high-seas adventures will inspire you.

Fifty years ago, Robin Lee Graham cruised into the Los Angeles harbor and made history, becoming at the time the youngest person to sail solo around the world.

The mariner was only 16 years old when he set forth nearly five years earlier, on July 27, 1965. His vessel: a 24-foot sloop called Dove. During his 1,739 days at sea traversing 30,600 nautical miles, Graham faced hurricanes, broken masts, crushing loneliness, a near collision with a freighter, and tedious weeks wallowing in the doldrums. But there were also moments of unparalleled beauty and long sojourns exploring fascinating destinations. He attended a memorial for a queen in Tonga, dived for shells in Fiji , safaried in South Africa’s Kruger National Park , hiked on lunar-like Ascension Island, ate piranhas in Suriname, and roamed the islands of the Galápagos .

Graham detailed his adventures in three National Geographic articles published between 1968 and 1970. “We sleigh-ride down into the deep trough of a trade-wind sea. Then Dove labors up the following crest, and down we plunge again, day after day, my boat and I,” he wrote in his first article. The teen’s quest captured hearts and imaginations, and readers avidly followed his journey and the challenges he experienced.

( Related: Discover stunning sailing adventures around the world . )

The most dramatic event was his second dismasting in the Indian Ocean. Only 18 hours out of the Cocos Islands , a roaring storm caused Dove’ s mast to buckle. Graham almost fell overboard—without his safety harness on—in the attempt to haul the trailing mast and sails back aboard. He sailed under a makeshift rig an astonishing 2,300 miles to Mauritius , off the coast of Africa . “Could I do it? I had no choice,” he wrote. “I had to; turning back against the trade winds was impossible.”

Published in 1972, Graham’s best-selling memoir, Dove (co-written with Derek L.T. Gill), expands on his articles and chronicles his love story with his wife, Patti, whom he met and married along the way. The book not only inspired countless mariners’ dreams but, as Graham also wrote, created “memories [at] landfalls where foreigners seldom set foot.”

“Dynamic, chaotic, brilliant. Both infinite and finite at once.” The seafarer pictured here might relate to how author Liz Clark describes the power of nature in Swell, her sailing memoir.

Graham is not the only seafarer with an extraordinary story. Here are 10 additional books—the latest installment in our ongoing Around the World in Books series—about adventurous sailors who test their mettle on the high seas.

Sailing Alone Around the World , by Joshua Slocum, 1900. Slocum’s iconic account of his solo trip around the globe—the first person to accomplish such a feat—can be found on almost every sailor’s bookshelf and was a prime inspiration to Graham. Setting off from Boston in 1895 in his 36-foot wooden sloop, Spray, Slocum sailed some 46,000 miles over three years. His wonderfully entertaining tale features close calls with pirates off Gibraltar, breakfasting on flying fish in the Pacific, and visiting with explorer Henry Stanley in South Africa .

Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail , by W. Jeffrey Bolster, 1997. Black seafaring wasn’t limited to the horrific Middle Passage . During the 18th and 19th centuries, thousands of Black sailors went to sea aboard whalers, warships, and clippers in pursuit of liberty and economic opportunity. They played a pivotal role in creating a new African-American identity, carrying news and information to Black communities ashore and even helping smuggle enslaved people to freedom—such as Frederick Douglass , who escaped from slavery disguised as a sailor.

The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float , by Farley Mowat, 1969. “The five hundred and fifty mile voyage across the center of Newfoundland was a prolonged exercise in masochism,” the Canadian author and naturalist writes in his hilarious account of his travails aboard the Happy Adventure . Beset by constant leaks, a cantankerous engine, and repeated sinkings, Mowat and his ornery wooden sailboat had a riotous time roaming the foggy shores of Newfoundland and the Maritimes in the 1960s.

( Related: 10 books that will take you on real-life adventures .)

The Curve of Time , by M. Wylie Blanchet, 1961. After being widowed, Blanchet turned to the sea, cruising with her five children on long summer sojourns in the 1920s and ’30s along the coast of British Columbia . A pioneer of family travel , Blanchet recalls in lyrical writing the beauty of the unspoiled Pacific Northwest and teaching her children the wonders of the natural world.

Maiden Voyage , by Tania Aebi, 1989. In 1985, Aebi’s father offered the 18-year-old a choice: go to college or sail a 26-foot boat around the world. She chose the boat. From surviving a terrifying collision with a tanker in the Mediterranean to braving a lightning storm off the coast of Gibraltar, her compelling memoir charts her two-and-half-year journey on Varuna as a young woman braving the sea alone with only her cat as companion.

The Last Grain Race , by Eric Newby, 1956. Windjammers once raced to carry grain from Australia to Europe the fastest, and Newby apprenticed aboard Moshulu during the final contest in 1939. Recounting his circumnavigation between Ireland and Australia, Newby captures the last era of big sailing ships.

Swell: Sailing the Pacific in Search of Surf and Self , by Liz Clark, 2018. Reading Aebi’s Maiden Voyage sparked Clark’s own dream to sail the world. Nominated for National Geographic Adventurer of the Year in 2015, Clark has captained her 40-foot sailboat throughout the Pacific for more than a decade. Her memoir weaves together life at sea, her love of the Earth, and her eternal quest for great surf.

Adrift: 76 Days Lost at Sea , by Steven Callahan, 1986. In 1982, several months after starting his voyage off the coast of Rhode Island, Callahan faced every sailor’s worst nightmare: His boat abruptly took on water and sank, leaving him stranded on a five-foot inflatable raft in the middle of the Atlantic. For the next 76 days, Callahan survived terrifying storms, shark attacks, and lack of food and fresh water while drifting 1,800 miles to the Caribbean .

The Cruise of the Snark , by Jack London, 1911. After reading Slocum’s book, The Call of the Wild author was determined to make his own grand voyage. London designed his dream boat, a 55-foot wooden ketch, and departed San Francisco in 1907 with his wife, Charmian, and a woefully inexperienced crew. On their travels through the South Pacific, London taught himself celestial navigation and learned how to surf in Hawaii before ending his trip in the Solomon Islands.

Taking on the World , by Ellen MacArthur, 2002. British sailor MacArthur holds the record for the fastest solo sail by a woman across the Atlantic and has circled the planet in record-breaking time. Her autobiography describes her extraordinary second-place finish (at the age of 24) in the world’s hardest single-handed yacht race, the Vendée Globe, where she faced frigid wind conditions, mountainous waves, and leaden skies in the Atlantic and Southern Oceans.

Related Topics

You may also like.

6 books about the UK to read this summer

Anyone can join this pioneering two-year conservation voyage

Free bonus issue.

This legendary Polynesian canoe will sail 43,000 miles, from Alaska to Tahiti

How to get active in the Maldives, from surfing to diving

How Scottish adventurer Aldo Kane is pushing the boundaries of exploration

Here's what makes the Drake Passage one of the most dangerous places on Earth

10 coastal adventures and activities to try right now

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- History & Culture

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Famous figures who had Titanic tickets but didn't make it on board

- As the Titanic was the height of luxury in 1912, some celebrities had tickets for its maiden voyage.

- But not all of them ended up boarding the ship.

- J. Pierpont Morgan and Milton Hershey were among those who missed the disaster.

The sinking of the Titanic in April 1912 still captivates us today, with numerous books, a multibillion-dollar movie , museums , and, controversially, expensive tours of the wreckage available.

Interest in the ship led to another maritime tragedy last year when an OceanGate submersible went missing on the way to the wreckage and was eventually confirmed to have imploded , killing all five people on board.

In the aftermath, stories emerged about people invited to participate in one of OceanGate's trips but decided against it — much like, more than 100 years ago, how people were fascinated with those who had almost been on the Titanic.

Here are seven notable figures, some of whom were among the richest people in the world, who were supposed to sail on the Titanic's maiden voyage but didn't — and four well-known people who were booked to go on a future journey with the ship.

Milton Hershey, the founder of Hershey's, sent the White Star Line a $300 check to reserve a spot on the Titanic, but he ended up sailing home on the SS Amerika instead.

As they aged, Hershey and his wife, Catherine, spent their winters on the French Riviera. In December 1911, the couple left for another extended European vacation. For their return journey, Hershey wrote a $300 check from the Hershey Trust Company to the White Star Line to reserve places on the maiden voyage of the company's brand-new ship, the Titanic.

According to Lancaster History , pressing business matters forced Hershey to cut his vacation short, and he left Europe just days before the Titanic would set sail, instead heading home on a German liner called the Amerika, which would later warn the Titanic about the dangerous amount of ice.

Hershey's canceled check is still in the possession of the Hershey Community Archives , and you can view it online.

J. Pierpont Morgan — yes, J. P. Morgan himself — had a personal suite on the Titanic and had attended its launch party in 1911. But he extended his French vacation and missed the sinking.

"I've never been able to find an authoritative 1912 source explaining the exact reason why J. P. Morgan canceled his passage on the Titanic," the Titanic expert George Behe told Reuters in 2021. Some speculated that the reasons were that he was in bad health or having issues with customs because of his art collection.

However, we know that Morgan, the cofounder of General Electric, International Harvester, and US Steel, was also the founder of the International Mercantile Marine, which in turn owned White Star Line. According to The Washington Post , he was even on hand to witness its 1911 launch.

"Monetary losses amount to nothing in life," Morgan told a New York Times reporter after the sinking. "It is the loss of life that counts. It is that frightful death."

Guglielmo Marconi, the Nobel Prize winner who invented the radio, opted to head to the US three days earlier on the Lusitania, forgoing a free ticket on the Titanic.

You might know that Marconi was considered a hero after the sinking of the Titanic because his invention, the wireless radio, helped ships in the surrounding area find where to look for the lifeboats.

But did you know he was almost on board the ship himself?

His daughter Degna wrote in her 1926 book, "My Father, Marconi," that he was offered a free ticket aboard the Titanic. But because his stenographer got seasick, Marconi opted to sail to the US on the Lusitania because he trusted that ship's stenographer more than Titanic's, Degna wrote.

Henry Clay Frick, the chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, missed the sailing of the Titanic because his wife sprained her ankle in Italy and needed to be hospitalized.

Visitors to New York City might recognize Frick's name from the Frick Collection or the Henry Clay Frick House. He was an important industrialist and a patron of the arts — and he was close to sailing on the doomed voyage.

"The Fricks booked the suite first, and then Mrs. Frick sprained her ankle while they were in Europe buying art and touring and things; so, they stayed behind to get medical attention," the historian Melanie Linn Gutowski told CBS News Pittsburgh in 2012.

"The suite that they booked, that some historians think that they booked, was some kind of savior suite in a way," she continued. "Everybody who booked it managed to survive either by not being on the ship, or jumping into a lifeboat at the last minute."

Eventually, the tickets made their way to J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. Controversially, he was one of the few men who made their way onto a lifeboat and survived. He was criticized for this for the rest of his life.

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt canceled his ticket on the Titanic at the last minute. He was on board the Lusitania when a German U-boat sank it in May 1915.

As a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt was a well-known member of New York society, so there was media coverage when it was revealed he'd narrowly escaped the Titanic.

Unfortunately, just a few years later, he was aboard the Lusitania , a British ocean liner that was sunk by German U-boats in 1915. He was one of the 1,200 passengers who did not survive the attack.

The American journalist Theodore Dreiser was persuaded by his publisher to take a cheaper ship home across the Atlantic.

Dreiser wrote about his brush with disaster in a chapter of his 1913 memoir, "A Traveler at Forty." Slate said the section about the Titanic, "The Voyage Home," was "one of the most gripping chapters in the memoir."

Dreiser wrote that he wanted to sail home with the rich and powerful people aboard the Titanic to get a peek at how the other half lived, but added that his publisher convinced him to sail home on the Kroonland, a cheaper ship, two days before Titanic sank.

"The terror of the sea had come swiftly and directly home to all," Dreiser wrote, according to Slate. "To think of a ship as immense as the Titanic, new and bright, sinking in endless fathoms of water. And the two thousand passengers routed like rats from their berths only to float helplessly in miles of water, praying and crying!"

John Mott, another Nobel Prize winner, was also offered a free ticket on the ship, but he chose a smaller ship, the Lapland, instead.

Mott, a Nobel Peace Prize winner who was the longtime leader of the YMCA, was another near-miss. Gorden R. Doss , a professor at Andrews University, said that Mott came close to death a few times.

First, he skipped the Titanic and opted for the Lapland. Three decades later, in 1943, he narrowly avoided a train crash.

Mott said, "The Good Lord must have more work for us to do" upon hearing about the sinking, according to Sotheby's .

There were other celebrities who had tickets to sail the Titanic in the future, had it not sank. J.C. Penney was set to sail on the ship's next trip from England to New York.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine , the founder of JCPenney was set to sail on the Titanic's second voyage from England to the US.

Frank Seiberling, the cofounder of Goodyear Tires, was booked to return to Southampton on the Titanic's next voyage.

The Akron Beacon Journal reported that Seiberling, the cofounder of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, and his wife frequently traveled to England and were huge admirers of English architecture. But one of their trips was postponed when their ship out of the States, the Titanic, sank.

So was John Alden Dix, the governor of New York.

Smithsonian Magazine also reported that Dix, the governor of New York from 1911 to 1913, was on the passenger list of the Titanic's return trip to England.

Henry Adams, a historian who was a descendant of President John Adams and President John Quincy Adams, was also booked on this trip.

"My ship, the Titanic, is on her way," Adams wrote in a letter on April 12, 1912, "and unless she drops me somewhere else, I should get to Cherbourg in a fortnight." As history tells, Adams was never able to board the ship and was forced to book passage elsewhere, The New Republic's Timothy Noah wrote.

- Main content

‘Dad said: We’re going to follow Captain Cook’: how an endless round-the-world voyage stole my childhood

In 1976, Suzanne Heywood’s father decided to take the family on a three-year sailing ‘adventure’ – and then just kept going. It was a journey into fear, isolation and danger …

W hen we lived in England my days had a familiar rhythm. Each morning, my mother flung open the curtains in my room, and I tugged my school jumper over my head and pulled on my skirt before tumbling downstairs to eat cereal with my younger brother Jon. After school, we’d play on the swing in our garden, or crouch at the far end of the stream to watch dragonflies hovering above the gold-green surface.

I was used to this rhythm; I liked it and thought it would never change. Until one morning over breakfast, my father announced that we were going to sail around the world.

I paused, a spoonful of cornflakes halfway to my mouth.

“We’re going to follow Captain Cook,” Dad said. “After all, we share the captain’s surname, so who better to do it?” He picked up his cigarette and leaned back in his seat.

“Are you joking?” I asked.

Next to me, Jon watched Dad, his lips parted.

“Not at all,” said my father, puffing out a cloud of smoke. “I’m deadly serious.”

“Well, someone needs to mark the 200th anniversary of Cook’s third voyage, don’t they?” he said, raising his eyebrows at my mother.

“Of course they do, Gordon,” said Mum, returning his smile.

“I’ve told you kids about the captain,” said Dad, stubbing out his cigarette in the ashtray. “He was an incredible man. The people who were going to recreate his first and second voyages didn’t get their act together in time, so this is the last opportunity.”

“How long will we be gone?” I asked.

“Three years. By the time we get back, you’ll have seen more places than most people will visit in a lifetime. We’ll sail down to South America, then cross the Atlantic Ocean to South Africa and Australia. From there, it’s on to Hawaii and Russia.”

The clock was ticking on the wall. I looked out of the window at the empty swing. Dad had taken us sailing before, but this was different.

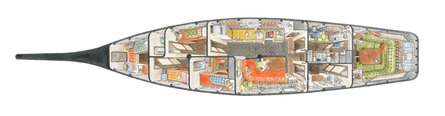

One evening later that summer, Dad announced that he’d found a boat. A few weeks afterwards, we went down to the Isle of Wight to inspect his find. He marched ahead at the boatyard. “You’re going to love her, I know you will,” he said, and I looked up to see an enormous boat with a long, curved bow, two masts and a raised deck at the stern.

The interior was unfinished, but bunks and cupboards were already taking shape, half-formed in the gloom.

After a while, I went up on to the aft deck to sit next to my father in the cockpit, watching him attach a compass to the binnacle, the wooden instrument stand in front of the ship’s wheel. “She’s called Wavewalker,” he said. “We were lucky – I was able to buy her because the man who was building her ran out of money.”

“Wavewalker,” I said, exploring the edges of the word. This boat would walk us over the waves, carrying us around the world and back again.

“B ut you’re so normal,” people often say when they find out about my childhood. And in some ways, I am. But, even if it’s not visible, my experience of spending a decade sailing 47,000 nautical miles on Wavewalker, equivalent to circumnavigating the globe twice, shaped who I am today.

I started thinking again about my past when my children were old enough to ask me about it. Did Dad really sail around the world because he wanted to honour Captain Cook? Why didn’t my parents, middle class and well educated themselves, worry about their children’s education or social isolation? Why was my relationship with my mother so difficult, particularly during my teenage years, and why didn’t my father try to help, when he must have seen how miserable I was?

My parents always claimed our time on Wavewalker was wonderful and told me I’d had a privileged upbringing. But this oft-repeated mantra conceals a much darker story. What I found, when I mustered enough courage to look back, was that many parts of my childhood were worse than I’d been willing to admit.

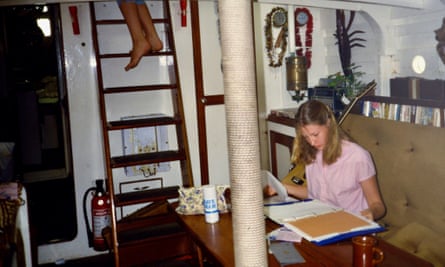

W hen I set sail from England with my parents, brother and three crew members in the summer of 1976, I was seven and thought the trip was going to be like an extended, exciting summer holiday. Once we’d settled into our ocean routines, Mum began giving Jon and me some schoolwork to do in the mornings, usually a maths or English worksheet. It was convenient that we were only a year apart in age, she said, since it meant she could teach us together. When I asked about other subjects, such as history, art or science, she said she wasn’t going to bother with those – if we were good at maths and English, everything else would sort itself out. Anyway, our voyage was like a massive geography field trip.

One day, about a week after leaving Gran Canaria, and a month after leaving England, a shadow appeared above the ocean’s southern rim. “I think it’s Ilha de Santo Antão in the Cape Verde islands,” said Dad, “which means we’re about 400 miles off the most westerly tip of Africa and halfway to Rio.”

The shadow darkened and gained substance, becoming a craggy rock lurking under a cloud, while the ocean filled with writhing jellyfish. The heat built until, one day, the breeze rotated through every direction and disappeared. “We’ve hit the doldrums,” said Dad when I went to stand beside him on the deck, gazing out at an ocean of thick honey. “They happen where the north and south trade winds meet. But that’s supposed to be a hundred miles south of here.”

We sat sweating under a blue bowl of sky for several days after that, each breath a gasp of heat that scorched the lungs. When the sun was up, I danced across the parched deck, searching for patches of shade, while Dad made a saltwater shower from a bucket punctured with holes that he hung in the rigging. At night, I slept on deck to escape the stifling air below, lying on my sleeping bag, and reaching up to grasp handfuls of the stars peppering the Milky Way.

After the wind returned, we saw a passenger ship ploughing its way towards us from South America. It came so close that I could see the people crowding its balconies and rails to wave, and when it swept past I saw its name etched on the stern: Brazilla.

“I wish we’d asked them for food,” I said, watching it go.

Dad laughed. “Don’t be silly.”

“There’s no fresh fruit left,” I said, giving him my sad look. “And I hate salt tablets.”

Salt was taking over my life. White tidemarks of it bloomed on my skin; my clothes and sleeping bag were sticky with it; and now I had to eat it as well, to stave off dehydration.

“Do you want to try some ship’s biscuits?” asked Dad, and when I nodded, he showed me where he’d hidden the tins under the step outside the main head, the name for the ship’s toilet.

“Do they have raisins in them?” I asked.

He shook his head and peered at my biscuit. “Oh, don’t worry about those: they’re only weevils. Tap it sharply on the table, and most of them will fall out and crawl away. The rest will give you useful protein.”

F rom South America, we sailed on to apartheid South Africa. We then set off across the notorious southern Indian Ocean towards Australia, this time with two inexperienced crew members on board, as my father had by then decided that he preferred to teach people how to sail himself. My father was a hero to me and, it seemed, to everyone else; and my mother was his glamorous, if somewhat unwilling, and unmaternal, accomplice.

On the first day of the new year, when we were partway across the Indian Ocean, I opened my eyes to a world I wanted to leave. I wanted to go home. I dragged myself from my bunk, taking care to avoid being hurled back against it when the boat veered the other way. The main cabin was deserted, so I huddled by the table, holding Teddy, my small brown bear, and wondered if anyone else was hungry. When my father came down, I wedged Teddy into the bookcase and followed him into the chartroom.

“How is it up there, Dad?” I asked. “Are the waves getting any better?”

He looked at me, his face expressionless. “No. They’re worse. They’re now over 50ft high. And the wind has changed direction to blow at storm force straight from the south pole.”

“Oh.” The hairs prickled on my neck.

He turned to lean over his chart. “It’s not good,” he said. He spoke the words quietly, as if to himself. Wavewalker’s quivering moments at the summit of each wave had become longer, and her plunges forward more extreme. Everything felt wet: my skin, my clothes, my hair, the floor and every surface I touched.

My fear felt physical – a cold lump I carried in my stomach. Every so often, if the wind wailed or our movement down a wave was particularly steep, my heart pounded and my legs felt weak.

Jon had joined me at the table by the time Mum struggled down the ladder in her oilskins several hours later. “Put on your lifejackets,” she said. “We’re going too fast. We must be prepared.”

I didn’t ask how a lifejacket would help us survive in an ocean full of gigantic, icy waves, and neither did Jon. There was little point in arguing, and, anyway, Mum was already halfway back up into the cockpit. When she returned later, Jon and I were sitting trussed up in our jackets by the table.

“Sue, come and help me make some food,” said Mum. “I need a can of corned beef.”

I nodded, gripping the countertop rail with one hand while unlatching a cupboard door with the other. The cabin tipped backwards. Wavewalker was climbing another watery mountain. This time the pause was endless. It felt as if time had been suspended, leaving us balanced on the head of a monstrous wave.

There was an explosion, and chunks of decking collapsed inwards above my head, followed by an avalanche of cold, grey water. As the boat lurched on to its side, my fingers let go and I was flung against the ceiling and back on to the galley wall. The air filled with screams, some of them mine.

Some time passed, though I don’t know how much. When I opened my eyes, I was lying on the floor of the main cabin, half-covered in water and surrounded by pieces of crockery, sodden books and hunks of decking. Icy water, black, grey and foaming white, flooded in through a hole above me. Jagged beams hung down from the ceiling, and one side of the cabin bulged inwards.

Mum was near the ladder. She tilted her head back to shriek through the hatch: “We’re sinking, Gordon! There’s a hole in the deck, and she’s full of water.”

I couldn’t get up – my legs didn’t want to move, and all I wanted to do was sleep. Maybe I could rest here, I thought, the water a blanket around me.

When I opened my eyes again I was lying in one of the top bunks in the four-berth cabin. Below me, the floor was covered with water and bits of debris – books, cushions, pieces of wood. Wavewalker felt full and drunk, and each time she tilted, water poured in through the hatch in the ceiling.

“Stop crying,” said Jon. “You’ve been crying for ages.”

I saw him lying on the bottom bunk on the other side of the cabin. He was right. I was crying.

He was clutching a square biscuit tin.

“Want one?” he asked, holding it up.

“No.” I tried to shake my head, but the pain made me stop.

I was wet, everything around me was wet, and some of the wetness was red. I closed my eyes, exhausted by the pain in my head. Dad appeared. He leaned over my bunk, his eyes underlined with curved shadows, his cheeks and nose red and inflamed.

“Are you OK?” he asked.

“I don’t think so.” My voice was a whimper.

He touched my right forearm, and I glanced down to see that his forefinger was dyed crimson.

“Why didn’t you tell me how bad this was?”

“I didn’t want to worry you,” I said, but really he hadn’t been there to tell.

“Do you think we’re going to die?” Jon asked after our parents had left.

“Probably,” I said, trying to put the lifejacket on without moving my head or touching the swelling above my eye. The lump seemed to be growing. It was taking me over, a foreign thing embedded in my head.

S omehow – miraculously – Dad managed to navigate us over the next few days to a tiny island in the middle of the Indian Ocean: Île Amsterdam . Even more miraculously, we were still afloat when we reached it, due largely to the continuous pumping done by our two crew members, and the tarpaulin and quick-setting cement Dad had spread across the huge hole in our deck.

We were greeted on Île Amsterdam by Commandant Ghozi, who told us he was leading a French scientific mission of 30 people there. He took me to be examined by a thin man in a white coat named Dr Senellart. “She has a broken nose, a fractured skull and there is blood trapped inside the swelling on her head,” he told my parents when we rejoined them in the waiting room.

I slipped my hand inside Dad’s. “What if we do nothing?” he asked.

“The swelling is pressing down on the fracture. If we do nothing, Monsieur Capitaine, your daughter could end up with brain damage. We must cut into the wound.”

For weeks, my mother kept taking me back to the tiny medical building where I underwent multiple operations on my head without anaesthetic, lying alone on the hospital bed. After my seventh operation, I went to find Mum in the waiting room.

“It is finished, Madame,” said Dr Senellart, following me in. “These,” he said, pointing to the shadows under my eyes, “will go in time. Your daughter is very brave.”

Mum, Jon and I were eventually rescued from Île Amsterdam by a passing container ship, while Dad sailed on with our two crew members to Fremantle in Australia in the dangerously damaged Wavewalker.

After repairing Wavewalker, we sailed from Fremantle to Sydney, and then across to New Zealand before turning north-east to make our way up to Hawaii. By the time we arrived in Honolulu, I was nine and we had been travelling for two years and 223 days. This was the point at which our trip was supposed to finish. Captain Cook had been killed in Hawaii, and we’d arrived there just over 200 years after his death.

But, of course, Dad had other ideas.

I n Hawaii, the months turned into years while Dad tried various schemes to raise money, including working in a boatyard, setting up an exhibition on our trip and asking for donations. My 12th birthday came around and I gave up counting the days in my diary. I was learning nothing and was going crazy with boredom, since my parents – for reasons I never understood – had decided not to send us to school.

One night my father came home and said that we needed a family conference. The discussion took place over a dinner of corned beef and cabbage, spiced up with Tabasco sauce.

“Well, we can’t stay in Hawaii for ever,” he said. “I think we have two options. We’ve finished our voyage, so we could go home through the Panama Canal.”

We all nodded.

“Or we could sail back down the Pacific.”

I felt sick. It was the first time that Dad had suggested we might not go back to England

“But if we did that,” I asked, “when would we go home?”

“What’s the hurry? Think of all the places we haven’t seen. We haven’t even been to Tahiti yet.”

I put my hand on the sofa’s red plastic cover. He was listing more destinations – Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea. Mum was nodding and smiling.

He glanced at me. “That’s enough discussion, Sue. It’s time to vote.”

I slumped against the seat. Mum folded a sheet of paper into quarters, ripping it along the creases. She pushed the pieces across the table towards us.

Everyone scribbled on the slips, which went into Dad’s blue felt captain’s hat, a blue boat on a wooden ocean that held our future.

Dad unfolded the first vote.

He smiled, and his hand dived back in. He spread out the second vote.

after newsletter promotion

I stared at the slips of paper, avoiding his eyes. No one said anything.

The third vote came out.

I wanted to look at Jon, but I couldn’t take my eyes off the final slip of paper, which would determine everything. Dad smoothed it out.

“Ah,” he said, “we have a draw.” He looked at Jon and me, and I sat up straight, ready to explain my choice.

My father glanced at Mum and knocked another cigarette out of the packet on the table. “What you kids must realise,” he said, leaning back and blowing out a mouthful of smoke, “is this isn’t a democracy, it’s a benevolent dictatorship. The captain always gets the casting vote.” He picked up his glass of rum and Coke and raised it towards us. “And I think we should go back down the Pacific.”

W e set off again. After a brief classroom experience in Queensland, Australia, some months later, I registered with a correspondence school, but finding the space and time I needed to study on board Wavewalker became a huge battle. My parents had by then started bringing paying crew on to the boat – advertising our voyages as “whale and dolphin sighting expeditions”. This turned our boat into a floating hotel in which I was expected to cook and clean for several hours a day. In addition, after I reached puberty, my relationship with my mother had deteriorated and she often didn’t talk to me for weeks on end, instead only referring to me in the third person, as if I was not there.

For the next three years we circled the Pacific. We were hit by another cyclone, and saw places like Tanna Island in Vanuatu, with its live volcano, remote Tikopia Island in the Solomons, and Marovo Lagoon in the New Georgia Islands, with its swamps and wood carvings. Meanwhile, I kept trying to study, hiding inside a sail to work so no one could find me to ask me to do more chores, and sending lessons back to the school whenever we reached a port that had a post office. I was trapped on Wavewalker against my will, with parents who didn’t seem to care how isolated or unhappy I was. I had no obvious way to get away – I had no money and no longer remembered any of my relatives or friends back in England. But, somehow, I trusted that if I educated myself enough it would help me escape.

I was 16 – and had been on Wavewalker for almost nine years – when Dad announced we were going to New Zealand. A few days after arriving in Auckland, Dad told us that he’d applied for the role of marketing manager at Hamurana Park, a tourist attraction several hours’ drive away, near Rotorua in the centre of New Zealand’s North Island. I had a thousand questions. Why was he applying for it? Would we stop sailing if he got it? What would then happen to Wavewalker? To name just a few. But when I tried to ask them, Dad shook his head. “Stop badgering me, Sue – if I get offered the job, then I’ll decide what we do.”

He set off in a hire car early one morning for his interview, squashed into his only suit. Later that day, we went to the yacht club to await his call. Mum took it when it came. “He got the job,” she told Jon and me afterwards. “We’re going to apply for New Zealand residency. The park’s owners want your dad to live in Rotorua, so we’ll find a school for Jon there.”

“But what about me?”

She hesitated. “Well, if your dad gets residency, you’ll get it, too. So you’ll be able to go to university in Auckland. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.”

When my father returned, he declared that we would stay in Auckland for Christmas before moving the boat down to the coastal city of Tauranga to start our annual repairs. Wavewalker would then be put into storage when he started his job. I nodded at this news. I didn’t want to stay in a country where I had no friends, but staying in one place was better than sailing, and, in any case, I’d learned not to argue with Dad’s decisions.

A couple of months later, Dad announced another decision – Jon and I were going to live in Rotorua on our own, so that Jon could start going to a school there. I would continue to learn by post, Dad told me, and would be responsible for looking after Jon, who was by then 15. When Wavewalker was repaired, he would start his job and come to live with us, while Mum kept sailing Wavewalker with another skipper, to make more money from paying crew.

“So what do you think?” asked Dad, after we had accelerated up a final short, steep track near Lake Rotoiti, and parked alongside two wooden holiday huts, known locally as “baches”.

“Is this where we’re going to live?”

“But where is Rotorua?”

“It’s about 40 minutes’ drive away. But it’s nice here – you’ll see.”

I followed Dad through the sliding door of the slightly larger bach. Inside was a small sitting room furnished with a sofa covered in a worn, mud-brown blanket. A pot-bellied stove faced it, its black paint fighting the rust creeping up its curved legs. A door led to a galley kitchen and, next to that, a small bathroom contained a twin-cylinder, top-loading washing machine that looked like it should be in a museum. The bach had one bedroom that I could use, and Jon was going to sleep in the second, smaller bach.

Dad returned to Tauranga, and I settled into a routine. Each morning, Jon came into the main bach for breakfast and I asked about his plans for the day, though he rarely said much. After he left to catch the school bus, I tidied up and took my books out to study on the veranda overlooking the lake.

When I tired of working, I’d row the house’s small dinghy out on to the water, pull in the oars and let it drift. It was there, lying on my back watching the birds loop and glide, that I allowed my thoughts to unravel. Wavewalker. Her movement backwards and forwards through the ocean. The dampness, the closed wooden cabins. My parents caught up in their own needs. Salt. Waves. Diesel. Dust. Boredom. Loneliness. Fear.

In late April, Dad returned to the bach to declare another change of plan. The skipper he’d hoped would take charge of Wavewalker wasn’t up to the task. Instead, he was going to resign from his job and sail the boat himself.

“You’re leaving again?” I asked, my voice faltering.

“Yes.” He avoided my eyes.

“When will you be back?”

“Well, we’re only partway through the first of three charters, so not until November.”

That was seven months away.

“How am I going to pay for things, Dad?” I said, my voice catching.

He hesitated. “Don’t worry. I’ll set up a separate account for you to use. I won’t be able to put much in it, so you’ll need to be very frugal.” He sipped his tea. “There’s one other thing. I need you to manage the bookings for the boat. There are spaces left on the trips for this year, so you’ll have to run some more advertisements.”

“Don’t worry, Sue,” he said. “I’ll ring whenever we get to a major port. And our friend Pam will help you if you need it.”

“But Pam lives three hours away in Auckland, Dad,” I said, still trying not to cry.

He got up. “I think we’d better call it a night, don’t you? I need to pack in the morning – your mum’s anxious for me to get back.”

O ne afternoon a few weeks later, I sat watching a stain on the sofa morph through a succession of shapes – a dolphin, a sail flapping, a man with a crooked nose, a laughing witch. Jon had left for school hours before, and I didn’t know how long I’d been sitting there. The Yellow Pages lay next to the phone. Almost without thinking, I picked it up, flicked through its pages and dialled the number for Childline.

“I don’t understand,” said the counsellor. “Where are your parents?”

“They’ve gone sailing.”

“When are they coming back?”

“November, I think,” I said, and the tears started.

I took a breath.

Then, in a rush: “I don’t know where they are. I don’t know when they’ll call again.”

“Are there any adults who can help you?”

“My parents have a friend called Pam, but she lives several hours away.

I caught my breath and kept answering the counsellor’s questions: “No, I’m not going to school. I sit here on my own all day, trying to teach myself.” My voice quavered.

“How are you feeling?” she asked.

“Not very well. I’m finding it hard to eat and I have a permanent headache.” I paused, trying to keep control. “As well as looking after my brother, I have to run my dad’s business.”

“Oh dear,” said the counsellor. She was trying to be helpful, but the hint of kindness in her words pushed me over the edge. “And … and … ” I said, tears running down my face, “and worst of all, I don’t want to be spending my time doing any of this. I need to be studying, or I won’t get into university.”

There was another pause. “None of this is your fault,” she said. “You’re coping with far more than is fair. I can’t change that, though I can be here if you need to talk.”

The counsellor did give me one piece of advice before the call ended:

“You can’t deal with this alone. If you try to, things will keep getting worse.”

The quiet engulfed me after I hung up the phone. I brought my legs up on to the sofa and buried my head between my knees.

M ore weeks passed. My call to Childline hadn’t changed my world, but it had allowed me to accept that it wasn’t my fault that I’d been left to look after my brother alone in New Zealand. It had also spurred me on to find a friend, a girl who lived on a caravan site nearby. But when winter arrived, a new worry started keeping me awake at night: my New Zealand visa was about to expire. I put on my smartest clothes – a T-shirt and denim skirt – and drove to Tauranga, where I was sent to wait in a long line in the immigration building. Some hours later, the man looked at my passport. “Where are your parents?”

“They’re away for a bit,” I said, trying to sound cheery. “But they’ll be back soon.”

The man’s frown deepened. My smile faded, and I felt small.

“Where exactly are your parents?”

He shook his head. “If they’re not in New Zealand, I can only extend your visa by two weeks. You’re a minor: you can’t stay here alone.”

Three days later, the phone went. Wavewalker had arrived in Fiji.

“Don’t worry,” said Dad, when I described my crisis, “I’ll come back.”

When my father turned up in New Zealand a few days later, we went back to the immigration department in Tauranga. This time, with him promising to stay and look after me in New Zealand, they agreed to extend my visa for four months until early October. It still didn’t get me to my final exams in November, but it at least got me closer.

Once again, Dad was in a hurry to leave, saying that Mum was waiting for him in Fiji and he had work to do on Wavewalker to get it ready to sail again.

More weeks passed. Somehow, I managed my loneliness and focused on the only thing that might help – studying as hard as I possibly could, staring at my books out on the wooden veranda. By doing this, I could make my way through each day without breaking down.

When October came, I went to the police station. “I only need a month’s extension to my visa this time,” I told the officer, while he thumbed through my passport.

He shook his head. “I can’t extend this any further unless you can show me an air ticket back to England.”

I went from the police station to the local travel agency, where another man hunted down flights. The cheapest option was a circuitous journey up to Japan and back down through Hong Kong that would cost $600.

“Are you sure there’s no cheaper ticket?” Dad asked, when at last he rang and I’d explained my predicament. “It’s a ridiculous price.”

I said nothing. I was clenching the phone so tight it hurt my hand.

“Well,” he said, after a long pause. “I guess I have no choice. I’ll move the money into the account.”

“Thanks, Dad,” I said, and, with three hours to go, I got the passport stamp I needed. I could stay in New Zealand until 10 days after my exams, but would then have to return to England after a decade away to face whatever waited for me there.

When my plane reached Tokyo, I stumbled out, carried along in a wave of travellers. I heard laughter and turned to see a girl looking at me. “You have a lot of luggage,” she said. “Let me help.”

By the time we reached the other end of the pristine terminal, we were laughing and almost crying over my absurdly heavy bags, and I’d discovered my new friend was called Hélène and would be sharing my next flight to Hong Kong.

“I’m going back to Paris to find a job and somewhere to live after a year of travelling in Australia,” she said. “What are you doing here on your own?”

It was a long story, but we had time. So I told her about Wavewalker, my childhood at sea, and my determination to escape and go to university. It was odd to talk about these things so far from where it had all happened.

“But what if you don’t get in?” she asked.

I shrugged, trying to ignore the ball of fear inside my stomach.

“I can’t go back.”

“Because at last I’m free.”

This is an edited extract from Wavewalker: Breaking Free by Suzanne Heywood, published by William Collins on 13 April. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy from guardianbookshop.com

Most viewed

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Review: YA sci-fi thriller ‘Voyagers’ doesn’t quite take off

This image released by Lionsgate shows Wern Lee in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Quintessa Swindell in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Lily-Rose Depp, left, and Tye Sheridan in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Viveik Kalra in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Tye Sheridan in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Archie Madekwe in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Tye Sheridan, left, and Lily-Rose Depp in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Colin Farrell in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Vlad Cioplea/Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows a scene from the film “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Lily-Rose Depp in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Lionsgate via AP)

This image released by Lionsgate shows Fionn Whitehead, left, and Lily-Rose Depp in a scene from “Voyagers.” (Vlad Cioplea/Lionsgate via AP)

- Copy Link copied

The most surprising thing about “ Voyagers ,” a sci-fi thriller about a group of young adults who have been tasked with travelling to and repopulating a new planet, is that it isn’t based on a Young Adult book series. Writer and director Neil Burger, who was also behind the “Divergent” films apparently decided to cut out the Intellectual Property middleman and make his own YA statement. That said, it does borrow heavily from quite a few other sources, with shades of “Lord of the Flies,” “The Giver,” “Ender’s Game,” “Euphoria” and any number of space madness films.

With a cast including Lily-Rose Depp, Tye Sheridan, Fionn Whitehead, Chante Adams, Archie Madekwe and Quintessa Swindell, nice-looking production design and a fast-moving plot, it’s a very watchable film. It also unfortunately suffers from the same problems as some of its IP-brethren —- it is dreadfully serious, fails to make the audience care very much about anyone involved and feels like it’s the first book in a series when all is said and done.

Set in the near future, “Voyagers” dumps vague information about earth’s deteriorating condition and a plan to send a group of people to another planet to start life anew. Since the journey is 86-years-long, it’ll be the grandchildren of the initial explorers. So they genetically engineer a group of racially diverse, suspiciously attractive geniuses for this first generation and shoot them off into space as young kids with only Colin Farrell’s Richard there to raise and monitor and counsel them. What could possibly go wrong with this terribly hasty plan?

Well, it certainly doesn’t help that a few years into the journey Whitehead’s Zac and Sheridan’s Christopher discover that they’re all being drugged to suppress their hormones and keep everyone semi-robotically focused on the mission instead shacking up with their crewmates. When they decide to stop taking the blue drink that it’s been hidden in, Zac turns immediately into a feral sex predator with an obsessive focus on Depp’s Sela. Soon enough everyone stops taking “the blue” and after Richard is hurt in an accident and there’s no supervision anymore, the ship devolves into a chaotic jumble of raging hormones, power struggles and paranoia and “The Lord of the Flies” parallels really start to take over. There’s even a Piggy-like character and a moment where a riled-up faction of the crew starts chanting “Kill!” Oh, the crew also starts to wonder whether there’s an alien aboard, as if there wasn’t already enough to chew on.

“Voyagers” has lofty ambitions and big, cliched questions about purpose, but one of the main problems is that it doesn’t do a great job of establishing its own characters. Part of that is likely due to “the blue” which makes everyone docile and emotion-free, but even after they stop taking it, the few characters who get personalities are painted with such broad strokes that there’s nothing to hold onto. Only Zac gets a real transformation, but there’s also no nuance to him. He’s a bad guy and a potential rapist with no discernable charisma, and it’s totally unclear why any portion of the crew would choose to follow him instead of the level-headed Christopher. Also, while the crew is quite racially diverse, 95% of the film is still laser focused on four white leads.

It’s the kind of premise that you can imagine would have been better served by a limited series with time to get to know and like at least some of the characters so that there are some stakes. We should be upset by Zac’s villainous devolution and torn by who might be the better leader. We should know more than three of the character’s names and care when people start dying. “Voyagers” is simply a semi-effective thriller with about as much emotional intelligence as its lab-produced, hormone-controlled, sequestered youngsters.

“Voyagers,” a Lionsgate release in theaters Friday, has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for “violence, some strong sexuality, bloody images, a sexual assault and brief strong language.” Running time: 108 minutes. Two stars out of four.

MPAA Definition of PG-13: Parents strongly cautioned. Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13.

Follow AP Film Writer Lindsey Bahr on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ldbahr

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

the book i'm reading is making me CRY 🧎🏻♀️ it's a time-travel romance where a couple goes back a year while being at summer camp! they're also going through some trouble and she just told him she wants to break up and oh my god 😭 YOU DESERVE EACH OTHER FANS, YOU WILL LOVE THIS. 30 May 2023 05:20:20

all the books i've received in december!!! thank you to everyone who has sent them to me https://t.co/K0k5WcuqeO. 27 Dec 2021

"i'm trying to not open the packages i've been getting for the past two days but it's hard it's tempting … lmao i know what it's in one and i want to see the books inside 😂 BUT I WANNA MAKE A BOOK HAUL/UNBOXING"

˚ ༘ ⋆。˚ latest book mail ˚ ༘ ⋆。˚ 26 Jun 2023 22:23:41

i should have waited 1 day for a book haul i got three new packages right now . 16 Nov 2022 19:52:08

"the first line of this book tho omg"

The latest tweets from @thebookvoyagers

😌😌💛💛. 06 Oct 2022 13:05:23

This is Sil. I'm a romance book blogger and now a booktuber too. I contribute to sites like Book Riot and Frolic and write fun listicles and book recommendation post. ... twitter: https://twitter ...

Tweets and Medias thebookvoyagers Twitter ( sil ♡ ) mexican blogger who loves romance books | she/her | 📧: [email protected] for any inquiries. Words in @BookRiot @buzzfeedbooks 🌿 Formerly @OnFrolic. menu. sil ♡ ... tweets about books i'm reading 📚, kdramas i'm watching 📺, woes i'm facing 😮💨, and raccoon memes ...

mexican blogger who loves romance books | she/her | [email protected] | Words in Book Riot + Buzzfeed Formerly Frolic. 827 Followers.

Hi, I'm Sil from The Book Voyagers. You can mainly find me on Twitter, but I've also taken a dive into the booktube world. I am a romance reader and blogger! I contribute to sites like Frolic and Book Riot. I hope this is an easier way to buy all my favorite books!

Page couldn't load • Instagram. Something went wrong. There's an issue and the page could not be loaded. Reload page. 3,312 Followers, 540 Following, 346 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from sil 🍒 (@thebookvoyagers)

183 likes, 3 comments - thebookvoyagers on July 16, 2023: "˚ ༘♡ ⋆。˚ all the books i got while i was on vacation — a haul! THANK YOU TO EVE..." sil 🍒 on Instagram: "˚ ༘♡ ⋆。˚ all the books i got while i was on vacation — a haul!

57 likes, 6 comments - thebookvoyagers on July 7, 2022: "when i actually read the books i say i'm going to read >>> lmao but i remember taking these p ...

And it's up to the Voyagers—a team of four remarkable kids and an alien—to gather them all and return to Earth. The Voyagers have made it to the last planet. If they complete this mission, they can finally go home. But they've been in space a long time, and it's starting to take its toll.

4:53. The Last Grain Race, by Eric Newby, 1956. Windjammers once raced to carry grain from Australia to Europe the fastest, and Newby apprenticed aboard Moshulu during the final contest in 1939 ...

61 likes, 0 comments - thebookvoyagers on November 11, 2021: "my life belongs to romance books. that's a fact "

sil ♡ X (Twitter) Stats and Analytics. thebookvoyagers has 28.8K followers, 1 / mo - Tweets freq, and 9.428661% - Engagement Rate. View free report by HypeAuditor.

59 likes, 2 comments - thebookvoyagers on July 5, 2022: "i've been reading a lot of celebrity romance books and IM NOT COMPLAINING 曆 i might be doi..." sil 🍒 on Instagram: "i've been reading a lot of celebrity romance books and IM NOT COMPLAINING 🦋 i might be doing a book list with some of my faves yay!

An image of a chain link. It symobilizes a website link url. Copy Link The sinking of the Titanic in April 1912 still captivates us today, with numerous books, a multibillion-dollar movie, museums ...

When I opened my eyes, I was lying on the floor of the main cabin, half-covered in water and surrounded by pieces of crockery, sodden books and hunks of decking. Icy water, black, grey and foaming ...

Effective from April 30th 2024, we will operate the Polaris service on a four week proforma, while maintaining three vessels on the service. The Polaris service will have a blank sailing once every four weeks, for four cycles, to increase the schedule buffer. This change will minimise disruptions from weather related events and improve ...

The most surprising thing about " Voyagers," a sci-fi thriller about a group of young adults who have been tasked with travelling to and repopulating a new planet, is that it isn't based on a Young Adult book series.Writer and director Neil Burger, who was also behind the "Divergent" films apparently decided to cut out the Intellectual Property middleman and make his own YA statement.