Ukraine war: international tourism hit as Russian travellers disappear

Senior Lecturer in International Tourism Management, Glasgow Caledonian University

Disclosure statement

Michael O'Regan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Tourism destinations globally are seeing a significant hit to their economies as Russians stay at home due to war-related sanctions , with possible long-term effects on international tourism.

This comes as European countries with Russian borders say they may ban all Russian tourists.

Russians were the world’s seventh biggest tourist spenders before the pandemic, splashing out US$36 billion (£31 billion) annually.

Vietnam’s Nha Trang , nicknamed “Little Russia” , attracted a large number of Russian tourists before the war. The beach resort saw a fast post-pandemic recovery thanks to the return of Russian tourists in 2019. Russian tourists spent an average of US$1,600 per stay in Vietnam, while the average for foreign visitors is US$900 .

Upmarket Vietnamese hotels, previously popular with Russian tourists, are almost empty or have been sold . The tour guide business has also been affected .

Nha Trang isn’t alone. In Thailand’s resort Phuket , shops and bazaars would normally be bustling with Russian tourists. Hotel companies remain uncertain about their future after many Russians cancelled their holidays when Russian airlines suspended flights to Phuket in March 2022. While foreign arrivals represented 59% of arrivals in Phuket airport before the pandemic, this figure was 35% in the first half of 2022 .

Read more: Ukraine war prompts Baltic states to remove Soviet memorials

Now resorts dotted around the globe, from Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt to Varadero in Cuba, are all suffering economic hits with low hotel occupancy levels , resulting in lost jobs, bankruptcies and falls in income .

Disappearing visitors

Turkey attracted seven million Russian visitors in 2019 to tourist destinations such as the Mediterranean resort of Antalya. It was popular with Russians because of its beaches, all-inclusive tours packages, and easy-to-obtain tourist visas on arrival . The city saw more than 3.5 million Russian visitors in 2021.

With forecasts of fewer than 2 million Russian tourists in 2022 and a US$3 billion to US$4 billion drop in tourism revenues, the change has led to job losses , just as fuel and other prices increase.

It’s an economic blow , as each tourist in Turkey generates roughly three temporary jobs and each tourism dollar generates up to US$2.50 worth of revenue for industries supplying tourist resorts , according to Al Jazeera.

The fall in tourist receipts and hard currency is putting pressure on the Turkish economy and its currency, as tourism accounted for 13% of GDP before the war and the pandemic.

Tourism issues

The EU has already suspended the European Union-Russia visa facilitation agreement, which made it relatively easy for Russians to obtain travel documents. Earlier sanctions had included bans on EU and Russian airlines flying to and from Russia. They also limited Russian tourists access to international credit overseas.

Many wealthy Russian tourists have switched to trips to Dubai. However, high-end shops in New York, London and Milan, and in glitzy destinations like St. Moritz and Sölden and popular spa towns such as Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic, are missing the business of the wealthiest Russian visitors.

On the French Côte d’Azur , luxury boutique hotels and expensive seafood restaurants have experienced a drop in business. They have not been able to replace wealthy Russian tourists with enough travellers from countries such as Bahrain .

Smaller countries, which hosted large numbers of Russian tourists as lockdowns eased, including Cyprus, the Maldives, Seychelles and the Dominican Republic found their post-pandemic tourism recovery short-lived. Cyprus, whose service industry including tourism, accounts for more than 80% of the economy is at risk of losing up to 2% of annual GDP if Russian and Ukrainian tourists do not return to the country.

Cuba saw an increase of 97.5% in Russian tourists in 2021, according to the country’s National Office of Statistics and Information . When that market collapsed , Cuba’s economic recovery plans were hit . Russians were expected to account for 20% of Cuba’s visitors in 2022, with far fewer tourists visiting the resort of Varadero .

Finding alternative visitors

Thai resorts are hoping for a growth in Middle Eastern visitors and Indians to help fill their hotels. Egypt is looking to increase visitor numbers from Latin America, Israel and Asia. Germans and others , including Iranians, are already replacing Russians in Antalya. In Vietnam, there are efforts to increase visitors from Korea, Japan, western Europe and Australia.

However, many destinations were unprepared for the shortfall in Russian tourists, and are not capable of replacing 30-40% of their market with new travellers.

Now that Russian tourists are cancelling trips to the resorts of Crimea as it comes under fire in the Ukraine war, some destinations are hoping Russians seek an escape by transiting through Serbia , Dubai and Qatar. Destinations such as Armenia, Vietnam and Turkey are also embracing the Russian payment system Mir to make it easier for Russian tourists to pay.

The efforts that destinations are making to replace Russian visitors will take considerable diversification, marketing and time, as tourists from new markets look for different activities. While Vietnam hopes for 5 million tourists in 2022, this is far from the 18 million visitors they received in 2019.

Even when the war ends, there is little likelihood that tourism will return to normal. Many European countries may not want to welcome Russian tourists for some time.

It will be interesting to see whether signs written in Russian in the Egyptian beach town of Sharm el-Sheikh or Varadero in Cuba will remain, or be replaced with Chinese or other languages in the upcoming tourist seasons.

- Ukraine invasion 2022

Scheduling Analyst

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

- Travel, Tourism & Hospitality ›

Leisure Travel

Travel and tourism in Russia - statistics & facts

Covid-19 impact on russians' travel destinations, impact of the war in ukraine on tourism in russia, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Russia 2019-2023

Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Russia 2019-2023

Tourism spending in Russia 2019-2022, by travel purpose

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Destinations

Leading outbound travel destinations in Russia 2021-2022

Number of outbound tourism trips from Russia 2014-2022

Leading source markets for travel to Russia 2020-2022, by arrivals

Related topics

Recommended.

- Inbound tourism in Europe

- Outbound tourism in European countries

- Travel and tourism in Europe

- Domestic tourism in European countries

- COVID-19: impact on the tourism industry worldwide

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Travel industry revenue distribution in Russia 2022, by segment

- Premium Statistic Tourism spending in Russia 2019-2022, by travel purpose

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Russia 2019-2023

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Russia 2019-2023

Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide from 2019 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Travel industry revenue distribution in Russia 2022, by segment

Distribution of travel industry revenue in Russia in 2022, by segment

Travel and tourism spending in Russia from 2019 to 2022, by purpose (in billion U.S. dollars)

Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Russia 2019-2023

Total contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia from 2019 to 2023 (in billion Russian rubles)

Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Russia 2019-2023

Total contribution of travel and tourism to employment in Russia from 2019 to 2023 (in million jobs)

Outbound tourism

- Basic Statistic Outbound travel expenditure in Russia 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound tourism trips from Russia 2014-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading outbound travel destinations in Russia 2021-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound tourists from Russia 2022, by territory

- Premium Statistic Outbound tourist flow growth in Russia 2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic European Union (EU) Schengen visas issued in Russia 2010-2021

Outbound travel expenditure in Russia 2011-2022

Outbound travel expenditure in Russia from 2011 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Number of outbound tourism trips from Russia from 2014 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of outbound travel visits from Russia from 2021 to 2022, by destination (in 1,000s)

Number of outbound tourists from Russia 2022, by territory

Number of Russians travelling abroad with tourism purposes in 2022, by territory (in 1,000s)

Outbound tourist flow growth in Russia 2022, by destination

Growth in outbound travelers with tourism purposes from Russia in 2022 compared to 2019, by selected destination

European Union (EU) Schengen visas issued in Russia 2010-2021

Number of Schengen Area visas issued from applications to consulates in Russia from 2010 to 2021*

Inbound and domestic tourism

- Basic Statistic International tourism spending in Russia 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading source markets for travel to Russia 2020-2022, by arrivals

- Basic Statistic Domestic travel spending in Russia 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of nature protected areas in Russia 2015-2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Estimated demand for inbound tourism in Russia Q1 2014-Q3 2023

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourist flow growth in Russia 2020-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of inbound tourist arrivals in Russia 2014-2022

International tourism spending in Russia 2011-2022

Spending of international tourists in Russia from 2011 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Leading inbound tourism markets visiting Russia from 2020 to 2022, by number of trips (in 1,000s)

Domestic travel spending in Russia 2019-2022

Domestic tourism expenditure in Russia from 2019 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Number of nature protected areas in Russia 2015-2022, by type

Number of nature conservation areas in Russia from 2015 to 2022, by type

Estimated demand for inbound tourism in Russia Q1 2014-Q3 2023

Estimated balance of demand for inbound tourism in Russia from 1st quarter 2014 to 3rd quarter 2023

Inbound tourist flow growth in Russia 2020-2023

Year-over-year growth in inbound tourism trips with tourism purposes in Russia from 2020 to 2023

Number of inbound tourist arrivals in Russia 2014-2022

Number of inbound tourism visits to Russia from 2014 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Travel companies

- Premium Statistic Travel industry organizations distribution in Russia 2022, by segment

- Premium Statistic Number of tourism companies in Russia 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Most popular travel websites in Russia 2023, by traffic

Travel industry organizations distribution in Russia 2022, by segment

Distribution of travel industry organizations in Russia in 2022, by segment

Number of tourism companies in Russia 2010-2022

Number of travel agencies and reservation service establishments in Russia from 2010 to 2022

Most popular travel websites in Russia 2023, by traffic

Leading travel and tourism websites in Russia in August 2023, by monthly visits (in millions)

Package tours

- Premium Statistic Number of package tours sold in Russia 2014-2021, by type

- Premium Statistic Value of package tours sold in Russia 2014-2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Package tour cost in Russia 2014-2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Most popular travel destinations on package tours in Russia 2022

Number of package tours sold in Russia 2014-2021, by type

Number of package tours sold in Russia from 2014 to 2021, by tourism type (in 1,000s)

Value of package tours sold in Russia 2014-2022, by type

Total value of package tours sold in Russia from 2014 to 2022, by tourism type (in billion Russian rubles)

Package tour cost in Russia 2014-2022, by type

Average cost of a package tour in Russia from 2014 to 2022, by tourism type (in 1,000 Russian rubles)

Most popular travel destinations on package tours in Russia 2022

Number of outbound tourists sent on tours by travel agencies in Russia in 2022, by destination (in 1,000s)

Transportation

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic airline passengers in Russia monthly 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Passenger traffic growth of airlines in Russia 2021

- Premium Statistic Travel transportation consumer price in Russia 2022, by type

Number of domestic airline passengers in Russia monthly 2020-2022

Number of passengers boarded by domestic airlines in Russia from January 2020 to May 2022 (in millions)

Passenger traffic growth of airlines in Russia 2021

Year-over-year growth rate in air passengers in Russia in 2021, by carrier

Travel transportation consumer price in Russia 2022, by type

Average consumer price of travel transportation in Russia in 2022, by type (in Russian rubles)

Accommodation

- Basic Statistic Paid travel accommodation services value in Russia 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Travel accommodation establishments in Russia 2022, by federal district

- Basic Statistic Total room area in travel accommodation in Russia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of visitors in hotels in Russia 2010-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of hotel visitors in Russia 2022, by travel purpose

- Premium Statistic Overnight accommodation cost in Moscow monthly 2020-2023

- Premium Statistic Hotel occupancy rate in Moscow 2023, by segment

- Premium Statistic Average daily hotel rate in Moscow 2023, by segment

Paid travel accommodation services value in Russia 2015-2022

Value of paid services provided by travel accommodation establishments in Russia from 2015 to 2022 (in billion Russian rubles)

Travel accommodation establishments in Russia 2022, by federal district

Number of collective accommodation establishments in Russia in 2022, by federal district

Total room area in travel accommodation in Russia 2013-2022

Total area of rooms in travel accommodation establishments in Russia from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000 square meters)

Number of visitors in hotels in Russia 2010-2022

Number of visitors in hotels and similar accommodation establishments in Russia from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of hotel visitors in Russia 2022, by travel purpose

Number of visitors in hotels and similar accommodation establishments in Russia in 2022, by purpose of travel (in 1,000s)

Overnight accommodation cost in Moscow monthly 2020-2023

Average cost of overnight accommodation in Moscow from May 2020 to September 2023 (in euros)

Hotel occupancy rate in Moscow 2023, by segment

Occupancy rate of quality hotels in Moscow from January to March 2023, by segment

Average daily hotel rate in Moscow 2023, by segment

Average daily rate (ADR) in hotels in Moscow from January to March 2023, by segment (in Russian rubles)

Travel behavior

- Premium Statistic Reasons to not travel long-haul in Russia 2022

- Premium Statistic Intention to travel to Europe in Russia 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Summer vacation plans of Russians 2012-2023

- Premium Statistic Travel frequency for private purposes in Russia 2023

- Basic Statistic Average holiday spend per person in Russia 2011-2023

- Premium Statistic Attitudes towards traveling in Russia 2023

- Premium Statistic Travel product online bookings in Russia 2023

Reasons to not travel long-haul in Russia 2022

Main reasons for avoiding travel outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in Russia from September to December 2022

Intention to travel to Europe in Russia 2019-2022

Index of intention to travel to Europe from Russia from January 2019 to December 2022 (in points)

Summer vacation plans of Russians 2012-2023

Where do you plan to spend your vacation this summer?

Travel frequency for private purposes in Russia 2023

Travel frequency for private purposes in Russia as of March 2023

Average holiday spend per person in Russia 2011-2023

How much money did you spend per person on holidays this summer? (in Russian rubles)

Attitudes towards traveling in Russia 2023

Attitudes towards traveling in Russia as of March 2023

Travel product online bookings in Russia 2023

Travel product online bookings in Russia as of March 2023

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Travel and tourism in Turkey

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Market intelligence.

- UN Tourism Data Dashboard

- UN Tourism World Tourism Barometer

- Impact of the Russian Offensive in Ukraine on International Tourism

- Publications on Tourism Market Intelligence

- Market Intelligence - Webinars

- COVID-19 and Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Impact of the Russian offensive in Ukraine on international tourism

UNWTO Tourism Market Intelligence and Competitiveness

Overall assessment of the impact on tourism

Added risk to a weak and uneven tourism recovery

Disruption of Russian & Ukrainian outbound travel

which accounts for some 3% of global spending = US$ 14 billion in 2020

Lower consumer confidence

particularly in more risk averse markets and segments

Impact on traditional destinations but also emerging ones

especially island and coastal destinations

Weaker economic growth and higher inflation

Higher oil prices + inflation + interest rates = higher travel costs for consumers & pressure on businesses, specially MSMEs

Threatens tourism-related jobs and businesses

impacting livelihoods

A risk to the ongoing recovery of tourism

First and foremost, the biggest concern is for the human tragedy unfolding in Ukraine. Our thoughts go to the people suffering from this conflict.

Russia’s military offensive in Ukraine represents a downside risk for international tourism. It has exacerbated already high oil prices and transportation costs, increased uncertainty and caused a disruption of travel in Eastern Europe.

The destinations most impacted so far (aside from Russia and Ukraine) are the Republic of Moldova with a 69% drop in flights since 24 Feb. (compared to 2019 levels), Slovenia (-42%), Latvia (-38%) and Finland (-36%) according to data from Eurocontrol. Russian bookings of outbound flights also plunged in late February and early March but have since rebounded according to data from Forwardkeys.

Despite the conflict, European air traffic has grown steadily from mid March to early May. Air bookings also show rising demand for intra European travel and for flights from the US to Europe.

The easing of travel restrictions are contributing to the normalization of travel (36 countries had lifted all COVID 19 related travel restrictions as of 13 May 2022) but the conflict continues to pose a serious threat to the recovery.

A possible loss of US$ 14 billion for the tourism economy

The military offensive risks hampering the return of confidence to global travel . The US and Asian source markets could be particularly impacted, especially regarding travel to Europe, as these markets are historically more risk averse.

As source markets, Russia and Ukraine represent a combined 3% of global spending on international tourism as of 2020. A prolonged conflict could translate into a loss of US$ 14 billion in tourism receipts globally in 2022.

In 2019, Russian spending on travel abroad reached US$ 36 billion and Ukrainian spending US$ 8.5 billion. In 2020, these values were down to US$ 9.1 billion and US$ 4.7 billion, respectively .

As tourism destinations, Russia and Ukraine account for 4% of international tourist arrivals in Europe but only 1% of Europe’s international tourism receipts .

The importance of both markets is significant for neighboring countries, but also for European sun and sea destinations. The Russian market gained significant weight during the crisis in long-haul destinations such as Maldives, Seychelles and Sri Lanka.

Russia and Ukraine's international tourism spending (% of world total)

Destinations with highest share of russian visitors (%) (various indicators) 2019-2021, european flights, january - april 2022 (% change vs. 2019), european countries with largest decline in number of flights 24 feb - 11 may 2022 (% change vs. 2019), air bookings for intra-european travel, january to may 2022 (index)*, air bookings for all outbound travel from russia january to may 2022 (index)*.

International tourist arrivals: 2020, 2021 and Scenarios for 2022 (monthly % change over 2019)

- Impact assessment, Issue 4 · 16 May 2022 (PDF)

- Impact assessment, Issue 3 · 28 April 2022 (PDF)

- Impact assessment, Issue 2 · 11 April 2022 (PDF)

- Impact assessment, Issue 1 · 24 March 2022 (PDF)

Wednesday, May 08, 2024 1:38 pm (Paris)

Russian tourism in Europe has changed since the conflict in Ukraine

Only the wealthiest Russians are visiting European Union countries today, while middle-class tourists have almost entirely disappeared.

By Marjorie Cessac

Time to 3 min.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Messenger

- Share on Facebook

- Share by email

- Share on Linkedin

Subscribers only

"Do you remember those dozens of tourist buses near the Opera Garnier [in Paris]? Today, you see a lot less of them, don't you?" A guide in France since 1994, Sergei Pankov has, unsurprisingly, lost a large part of his clientele since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. "Before, I worked with people who came from everywhere, including Vladivostok [in Siberia]. People from the middle classes and pensioners, for example," he explained.

Fans of organized tours have now disappeared, replaced only by individual tourists who are usually extremely rich. "They sometimes stay at the Shangri-La [a luxury Parisian hotel], or rent a private boat at €800 for a one-and-a-half-hour trip with champagne on the Seine, knowing that it costs €5,000 with dinner," said Pankov. The Opera Garnier, the Louvre, Versailles: they take in the great classics. "We discuss geopolitics, but I'm careful, because there are divided opinions, and our goal is referencing culture and history, not getting involved in politics." Sometimes, he added, some people inquire beforehand about the risk of possible aggression against Russian speakers.

The war has not completely dried up Russian tourism in Western countries, even if it has changed its face. With sanctions and the closure of European airspace to Russian airline companies and the private jets of oligarchs at the end of February 2022, these travelers must now stop in Istanbul, Belgrade, Yerevan, Podgorica or even Dubai, if they want to reach the European Union (EU).

Increased scrutiny of visa applications

"Visiting from Russia today is expensive – extremely expensive – and takes much longer," confirmed Sveta Azur, a guide from Central Asia, working in Nice. As a result, her clientele, like that of other professionals, is mainly made up of Russians living in the EU, London, Israel or the United States, usually with two passports or a residence card. "About 90% live in Europe and 10% come from Russia," she said, also noting the presence of Ukrainian tourists. This is confirmed by Vladimir Yatsko, a Belarusian guide for forty years in Paris: "The week [of May 8], a couple came from Kyiv to escape the war and rest," he said.

The conflict has reshuffled the cards according to both budget and geopolitical affinities. In the EU, since September 2022, there has been increased scrutiny of visa applications for the Schengen area. According to the French Ministry of Tourism, referring to estimates by Oxford Economics, the number of Russian visitors to France – around 310,000 people in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic – was only 99,300 in 2022.

You have 49.12% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.

Lecture du Monde en cours sur un autre appareil.

Vous pouvez lire Le Monde sur un seul appareil à la fois

Ce message s’affichera sur l’autre appareil.

Parce qu’une autre personne (ou vous) est en train de lire Le Monde avec ce compte sur un autre appareil.

Vous ne pouvez lire Le Monde que sur un seul appareil à la fois (ordinateur, téléphone ou tablette).

Comment ne plus voir ce message ?

En cliquant sur « Continuer à lire ici » et en vous assurant que vous êtes la seule personne à consulter Le Monde avec ce compte.

Que se passera-t-il si vous continuez à lire ici ?

Ce message s’affichera sur l’autre appareil. Ce dernier restera connecté avec ce compte.

Y a-t-il d’autres limites ?

Non. Vous pouvez vous connecter avec votre compte sur autant d’appareils que vous le souhaitez, mais en les utilisant à des moments différents.

Vous ignorez qui est l’autre personne ?

Nous vous conseillons de modifier votre mot de passe .

Lecture restreinte

Votre abonnement n’autorise pas la lecture de cet article

Pour plus d’informations, merci de contacter notre service commercial.

Ukraine crisis clouds Southeast Asia’s fragile tourism recovery

A decline in Russian visitors is expected to hit Southeast Asian destinations like Phuket and Bali hard.

Bali, Indonesia – Travel industry figures fear the war in Ukraine could derail the much-anticipated recovery of tourism-dependent economies in Southeast Asia just as COVID-19 travel restrictions are finally being lifted across the region.

The Philippines, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand are now open to vaccinated travellers, albeit with costly and cumbersome protocols. Indonesia recently announced it would restart quarantine-free travel in Bali by March 14, while Vietnam plans to reopen to tourists on March 15.

Keep reading

Biden administration shields ukrainians in us from deportation, us: former officer cleared in shooting during breonna taylor raid, latest ukraine updates: us slams russian nuclear plant attack, russians advance towards ukraine’s largest nuclear power plant.

The most recent World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) Panel of Experts’ survey found nearly two-thirds of travel professionals expected their fortunes would improve this year on the back of easing border restrictions and positive data from 2021.

Global tourism receipts for 2021 reached $1.9 trillion, up 19 percent compared with the previous year, according to the UNWTO. Overall global passenger traffic improved eight percentage points, with demand down 58 percent compared with 2019, according to the International Air Transport Association – although the Asia Pacific’s recovery lagged other regions.

But the war in Ukraine, sanctions against Russia and airspace restrictions have dampened projections in a region where Russians became the largest and most spendthrift group of visitors for many top destinations during the pandemic, displacing Chinese unable to travel due to their country’s strict border controls.

The fallout is already being felt in popular destinations such as the Thai resort island of Phuket, where Russians account for 51,000 of the 278,000 foreigners who visited the island between November and February, according to the Tourism Authority of Thailand.

“We have been speaking to many hoteliers that are reporting a lot of cancellations because of reduced air traffic,” Bill Barnett, director of C9 Hotelworks, a consultancy in Phuket, told Al Jazeera.

Gary Bowerman, a travel analyst based in Kuala Lumpur, said Russian visitors have been a priority market for destinations including Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia’s Bali since the decline in Chinese tourists.

“So for sure the war will affect those countries’ re-openings,” Bowerman told Al Jazeera.

In Bali, Russia quickly overtook Australia as the largest source of tourists after Canberra banned its residents from travelling abroad, with 68,000 Russian nationals flying to the island in 2020, according to Statistics Indonesia.

Russians’ spending on food, accommodation, transport and tours has provided vital economic stimulus for the island, where tourism accounted for 60 per cent of gross domestic product before the pandemic.

But with the value of the rouble plunging to record lows, the number of Russians who can afford to travel overseas is set to shrink. Just getting there is likely to be a challenge.

Last month, Singapore Airlines, one of the few airlines offering regular international flights to Bali, announced an immediate and indefinite suspension of its service between its hub of Changi Airport and Moscow.

“Things are a total mess back home. Prices are skyrocketing, people will start losing their jobs and the bandwidth for withdrawing money is getting narrower,” Jaleel Mubarak, a Russian IT professional based in Bali who is preparing to fly home to be with his children, told Al Jazeera.

“Technically leaving Russia will become very challenging soon and I think Indonesia will also get in line with the Western world with sanctions,” said Mubarak, referring to Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s statement that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was “unacceptable”.

Rising oil prices

Tourists from Russia and Ukraine will not be alone in facing new challenges flying to Southeast Asia as a result of the conflict.

Russia accounts for about 10 percent of the world’s supply of crude oil, and markets are bracing for serious disruptions due to sanctions and possible retaliation by Moscow. On Wednesday, the global benchmark hit $115 per barrel just days after breaching the crucial $100 mark for the first time since 2014.

“If you look at the bigger picture, oil is now more than $100 a barrel and if it stays there or goes even higher, the price of jet fuel will go through the roof,” said Bowerman, the Kuala Lumpur-based analyst. “Normally after a lull like COVID, airlines would launch extra flights and discount fares to win back the market. But the price of jet fuel is going to make discounting impossible.”

Bowerman said airlines could struggle to obtain sufficient supplies of fuel.

“Long-haul airlines will be scrambling just to find it,” he said. “The potential for this to draw down global demand for air travel is significant.”

The banning of Russian planes from airspace over the United States, European Union, United Kingdom and Canada, along with retaliatory bans by Russia, puts a further dampener on the recovery.

Flying around Russia, the world’s largest country and a bridge between Europe and Asia, will add hours to flight time on some routes. Just one extra hour of flight time adds between $11,000 and $20,000 to the cost of a journey, according to John Gradek, a lecturer of aviation management at McGill University.

Flights between Europe and East Asia will be most affected in the immediate term. Airlines including Finnair and JAL have already cancelled or rerouted flights to top destinations, including Tokyo, Seoul, Shanghai and London. But the bans lay another speed bump on the road to recovery for tourism-dependent economies in Southeast Asia.

“People are not going to say we won’t travel overseas because there is a war going on in Europe,” said Barnett, the Phuket-based consultant.

“But we have not yet seen the full financial impact of the war on oil prices and inflation. If the European market goes down and China doesn’t come back, it won’t be a good thing for an already volatile market.”

How Russia’s War on Ukraine Changed Travel One Year Later

Rashaad Jorden , Skift

February 23rd, 2023 at 12:00 PM EST

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the travel industry in significant ways, and its impact will continue to be felt for many years. Here is Skift's look at how the war has altered the business of travel.

Rashaad Jorden

Friday marks the one-year anniversary of the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a cataclysmic act that has significantly impacted travel worldwide. In just 12 months, 19 million refugees have crossed the border out of Ukraine, 7,200 innocent civilians have been killed, including 438 children, and countless lives are still being put at risk day and night by a war that shows no signs of ending.

That is how all of us try to put the tragedy into perspective. Still, our job is to report on the travel industry and how this war has upended business.

Major travel brands in all sectors of the industry have been disrupted. Skift has thoroughly covered the impact of the war on the travel industry, including changes travel brands have had to make in response to the invasion as well as how it has impeded travel’s ongoing recovery from the pandemic. Here is a look at major changes in travel brought about by the war.

Airlines Faced Surging Fuel Costs

The airline industry was perhaps the first sector of travel to feel immediate effects of the war. Still largely yet to make a complete recovery from the pandemic, airlines had to quickly encounter surging fuel prices . Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary predicted the 12 months after the invasion would be difficult for most airlines in large part because of the jump in oil prices. Some carriers either introduced or raised fuel surcharges , which airlines typically pass onto customers in the form of higher airfares .

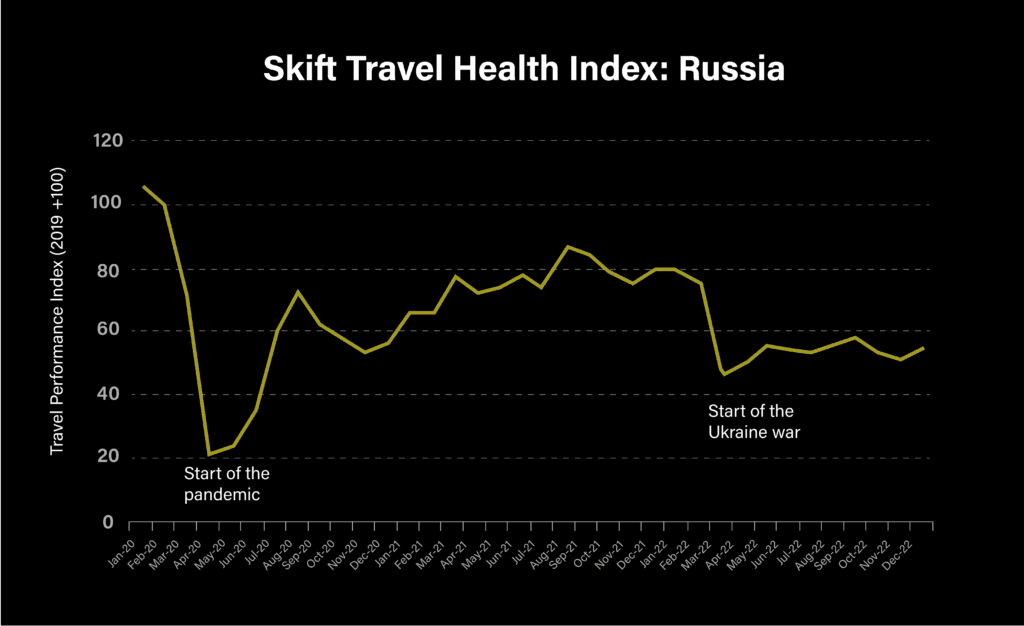

Russia’s Travel Industry Hasn’t Recovered

Russian travelers spent $36 billion on international travel and took more than 40 million overseas trips in 2019 , making the country one of the world’s largest outbound markets. The Russian travel industry had initially been one of the strongest performers according to the according to the Travel Health Index launched by Skift Research, which measures the performance of the global travel industry compared to pre-pandemic levels.

But moves by U.S. , Canada, and nations across Europe to close their airspace to Russian planes have pummeled Russia’s travel performance as calculated by Skift Research. Russia’s score in the Skift Travel Health Index, which reveals the extent of its recovery from the pandemic, decreased roughly 28 points from February 2022 to the following month. The country’s December 2022 performance trailed its score from the same month in 2020.

The War Drove Major Travel Brands to Retreat From Russia

Many major Western travel companies announced shortly after Russia invading Ukraine that they were pulling business out of Russia . Travel industry heavyweights like Airbnb, Booking Holdings and Marriott were among the corporations to announce they were pulling operations out of Russia. In addition, several tour operators committed to cancelling trips to Russia for the rest of 2022.

However, some prominent global brands are still doing business in Russia, including Accor. CEO Sebastien Bazin said during last year’s Skift Forum Europe that the Paris-based hotel company has never stopped operating in a war-torn country in its history. Bazin added that issues pertaining profitability didn’t drive Accor’s decision, noting that Russia has been far from a lucrative market from the company. Meanwhile, despite blocking advertising from Russian companies, Google Travel is still listing information about hotels in Russia provided by advertisers from outside of the country.

Skift published this list in March 2022 documenting companies that had announced they were curtailing business from Russia.

Russian Travelers Forced to Move on From Long-Time Popular Destinations

Countries like Estonia, Latvia and Finland that long relied on Russian travelers took steps to restrict visitors from one of their top source markets. Estonia banned entry to Russian citizens who had previously issued tourist visas while Latvia stopped granting its own tourist visas to Russian travelers. Meanwhile, Finland limited the number of tourist visas it issued to Russian citizens. Skift Global Tourism Reporter Dawit Habtemariam writes those measures were part of a collective strategy to exert pressure on Russia’s government to end the invasion of Ukraine. In addition, Poland barred Russian tourists from entering the country .

The war also accelerated Cyprus’ plans to diversify its tourism base as the Mediterranean island nation banned flights from Russia. Cypriot Deputy Tourism estimated Savvas Perdios estimated the Russian and Ukrainian markets had represented roughly 22 percent of his country’s tourist arrivals, a figure he said went down to zero.

However, Thailand , the Maldives and Dubai have welcomed Russian visitors. The resumption of direct flights from Russia to Thailand sparked a nearly sevenfold increase in Russian visitors from September to November last year, and Thai authorities expect more than 1 million Russian travelers to visit in 2023.

And Dubai and Maldives have grown in popularity for Russian travelers, with Russia serving as among the top source market for both destinations. One Russian national living in the United Arab Emirates said the country was one of the few nations were Russians could travel without difficulty.

Companies and Destinations Hit Hard by the Absence of Russian Travelers

Aleksander Karpetsky, CEO of Dominicana Pro , a Dominican Republic-based tour operator specializing in trips for Russian and Ukrainian travelers, said the lack of visitors from his company’s markets had left his workers unemployed. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s travel industry and economy took a major hit after the state-owned Vietnam Airlines suspended flights to and from Russia shortly after the start of the war. Less than 40,000 Russians traveled to Vietnam in 2022, a nearly 94 percent drop from roughly 650,000 in 2019. In addition, Russian travelers typically spend more than visitors from other countries, according to data gathered from the Vietnam National Administration of Tourism.

Turkey Becomes Business Travel Hub for Displaced Russian Corporations

Turkey’s decision not to issue sanctions against Russia drove a large number of Russian companies to set up shop in the country . Close to 1,400 Russian business opened offices in 2022, more than any other nation. Corporate Travel Editor Matthew Parsons wrote that Russian corporations view Turkey as a neutral trading location because the country enables them to trade with firms prohibited from engaging directly with Russia, especially U.S. businesses. Hundreds of U.S. corporations set up in Turkey after closing their Russian operations.

The number of flights between the two countries has also increased in recent years. Flights from Russia to Turkey rose 45 percent in 2022 compared to the previous year. And Turkish Airlines is upping the number of seats to and from Russia for the upcoming April-to-June quarter 55 percent from 2019 levels.

Foreign Visitation to Ukraine Rendered Impossible

Although domestic tourism has started to rebound , reaching up to 50 percent of pre-invasion levels , the State Agency for Tourism Development of Ukraine is still urging foreign travelers not to visit the country until the end of the war because it can’t guarantee their safety .

Mariana Oleskiv, chairperson of the State Agency for Tourism Development of Ukraine, is adamant though that Ukraine will be successful in its efforts to rebuild its tourism industry. She delivered an emotional speech on the subject at Skift Global Forum in New York last September, explaining why she’s hopeful about a brighter tourism future for Ukraine. Oleskiv cited Ukraine’s plans to use Crimea, a region currently occupied by Russia, as a destination that could spark Ukraine’s tourism recover.

Russia Looks to Fill Tourism Void With Indian Travelers

Seeking ways to rebound from the enormous tourism hit, Russian tourism authorities turned their focus to wooing visitors from what Moscow perceived as friendly nations — one of them being India . Russia increased their efforts to attract Indian tourists, sending officials to events in India such the Outbound Travel Mart in Mumbai in September. Russian President Vladimir Putin had also proposed visa-free travel between the two countries.

Corporate Travel Agency Relationships Made Complicated

Not only did corporate travel agencies have to conduct emergency repatriations of staff based in Ukraine , they had the thorny issue of how to handle relationships with Russian partners . Many corporate travel agencies have long had ties in Russia because they viewed a presence in the world’s largest country as crucial. While CWT and FCM Travel said they would continue to maintain ties with their Russian partners, Corporate Travel Management suspended its partnership with Moscow-based Unifest and TripActions, which later rebranded as Navan, said it was is no longer supporting travel to Russia and Belarus.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Tags: russia , russia outbound , ukraine , ukraine national tourism organization , Ukraine War

Photo credit: A collage created by Skift Creative Strategist Aishwarya Agarwal Aishwarya Agarwal

- Interfax Group

- Due diligence & KYC

- Reputational Risk

- News Products

- Top Stories

- Exclusive Interviews

- Press Releases

- REQUEST A DEMO

Russia sees almost 30% decline in inbound tourism in 2022 - Border Service

MOSCOW. Feb 8 (Interfax) - Over 200,000 foreign tourists visited Russia in 2022, down 28.8% from the year before, the Federal Security Service (FSB)'s Border Service said in its statistical report.

A total of 205,100 foreigners visited Russia as tourists last year, it said.

Most of the tourists came from Germany (25,300, or 33.4% fewer than the year before), followed by Turkey with 22,600 tourists (down 2.5%) and Iran with 14,600 tourists, up 25 times from 2021.

Also in the top five are Kazakhstan (13,270 tourists) and Cuba (11,300). They are followed by Uzbekistan (8,860), Kyrgyzstan (6,600), India (6,400), the United States (5,580) and Armenia (5,200).

Israel, Latvia, the United Arab Emirates, Serbia, Azerbaijan, South Korea, Turkmenistan, Italy, France and Lithuania are in the top 20.

Inbound tourism in Russia drastically fell amid the coronavirus pandemic. The border closure in 2020 cut tourist arrivals 93%, compared to 2019 when Russia was visited by over 5 million foreign tourists. There were 288,000 foreign tourist arrivals in Russia in 2021, or 14% less than in 2020.

- Privacy Policy

News and other data on this site are provided for information purposes only, and are not intended for republication or redistribution. Republication or redistribution of Interfax content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Interfax.

© 1991—2024 “Interfax Information Group” www.interfax.com. All rights reserved.

Want to comment on Asia Times stories?

Sign up here

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Covering geo-political news and current affairs across Asia

The disappearing Russian tourist

Share this:

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tourism destinations globally are seeing a significant hit to their economies as Russians stay at home due to war-related sanctions , with possible long-term effects on international tourism.

This comes as European countries with Russian borders say they may ban all Russian tourists.

Russians were the world’s seventh biggest tourist spenders before the pandemic, splashing out US$36 billion annually.

Vietnam’s Nha Trang , nicknamed “Little Russia” , attracted a large number of Russian tourists before the war. The beach resort saw a fast post-pandemic recovery thanks to the return of Russian tourists in 2019. Russian tourists spent an average of $1,600 per stay in Vietnam, while the average for foreign visitors is $900 .

Upmarket Vietnamese hotels, previously popular with Russian tourists, are almost empty or have been sold . The tour guide business has also been affected .

Nha Trang isn’t alone. In Thailand’s resort Phuket , shops and bazaars would normally be bustling with Russian tourists. Hotel companies remain uncertain about their future after many Russians canceled their holidays when Russian airlines suspended flights to Phuket in March 2022.

While foreign arrivals represented 59% of arrivals in Phuket airport before the pandemic, this figure was 35% in the first half of 2022 . Now resorts dotted around the globe, from Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt to Varadero in Cuba, are all suffering economic hits with low hotel occupancy levels , resulting in lost jobs, bankruptcies and falls in income .

Disappearing visitors

Turkey attracted seven million Russian visitors in 2019 to tourist destinations such as the Mediterranean resort of Antalya. It was popular with Russians because of its beaches, all-inclusive tour packages and easy-to-obtain tourist visas on arrival . The city saw more than 3.5 million Russian visitors in 2021.

With forecasts of fewer than 2 million Russian tourists in 2022 and a $3 billion to $4 billion drop in tourism revenues, the change has led to job losses , just as fuel and other prices increase.

It’s an economic blow , as each tourist in Turkey generates roughly three temporary jobs and each tourism dollar generates up to $2.50 worth of revenue for industries supplying tourist resorts , according to Al Jazeera.

The fall in tourist receipts and hard currency is putting pressure on the Turkish economy and its currency, as tourism accounted for 13% of GDP before the war and the pandemic.

Tourism issues

The EU has already suspended the European Union-Russia visa facilitation agreement, which made it relatively easy for Russians to obtain travel documents. Earlier sanctions had included bans on EU and Russian airlines flying to and from Russia. They also limited Russian tourists’ access to international credit overseas.

Many wealthy Russian tourists have switched to trips to Dubai. However, high-end shops in New York, London and Milan, and in glitzy destinations like St Moritz and Sölden and popular spa towns such as Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic, are missing the business of the wealthiest Russian visitors.

On the French Côte d’Azur , luxury boutique hotels and expensive seafood restaurants have experienced a drop in business. They have not been able to replace wealthy Russian tourists with enough travelers from counties such as Bahrain .

Smaller countries, which hosted large numbers of Russian tourists as lockdowns eased, including Cyprus, the Maldives, Seychelles and the Dominican Republic found their post-pandemic tourism recovery short-lived.

Cyprus, whose service industry including tourism, accounts for more than 80% of the economy is at risk of losing up to 2% of annual GDP if Russian and Ukrainian tourists do not return to the country.

Cuba saw an increase of 97.5% in Russian tourists in 2021, according to the country’s National Office of Statistics and Information . When that market collapsed , Cuba’s economic recovery plans were hit . Russians were expected to account for 20% of Cuba’s visitors in 2022, with far fewer tourists visiting the resort of Varadero .

Finding alternative visitors

Thai resorts are hoping for a growth in Middle Eastern visitors and Indians to help fill their hotels. Egypt is looking to increase visitor numbers from Latin America, Israel and Asia. Germans and others , including Iranians, are already replacing Russians in Antalya. In Vietnam, there are efforts to increase visitors from Korea, Japan, Western Europe and Australia.

However, many destinations were unprepared for the shortfall in Russian tourists, and are not capable of replacing 30-40% of their market with new travelers.

Now that Russian tourists are canceling trips to the resorts of Crimea as it comes under fire in the Ukraine war, some destinations are hoping Russians seek an escape by transiting through Serbia , Dubai and Qatar. Destinations such as Armenia, Vietnam and Turkey are also embracing the Russian payment system Mir to make it easier for Russian tourists to pay.

The efforts that destinations are making to replace Russian visitors will take considerable diversification, marketing and time, as tourists from new markets look for different activities. While Vietnam hopes for 5 million tourists in 2022, this is far from the 18 million visitors they received in 2019.

Even when the war ends, there is little likelihood that tourism will return to normal. Many European countries may not want to welcome Russian tourists for some time.

It will be interesting to see whether signs written in Russian in the Egyptian beach town of Sharm el-Sheikh or Varadero in Cuba will remain, or be replaced with Chinese or other languages in the upcoming tourist seasons.

Michael O’Regan , Senior Lecturer in International Tourism Management, Glasgow Caledonian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Subscribe to our newsletters:

- The Daily Report Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

- AT Weekly Report A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

Eurasia Review

A Journal of Analysis and News

Ukraine War Hits Russia’s Tourism Industry – OpEd

By Kester Kenn Klomegah

Russia’s tourism, both in-bound and out-bound, is severely hit by the war-ravaged crisis that unfolded in the former Soviet republic of Ukraine late February. For more than two years, the tourism industry was affected due to the widespread Covid-19 that shattered the world.

Industry operators say that the impact on tourism due to Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine has pushed the United States and Canada, European Union, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries to impose a series of sanctions, which are currently affecting the smooth operation of tourism business.

According to statistics, over these past three years that included the Covid-19 restrictions and Russia-Ukraine crisis, foreign airlines have carried an estimated 128.1 million passengers, but most passengers were stuck due to border closures and repatriated in 2020. As Covid-19 subsided, and the latest volley of sanctions have cut foreign travel especially to the United States and Europe for Russians.

Analysts expect tourism business to develop considerably inside Russia. Russian tourists might instead opt for South America and Caribbean, Asian and African destinations such as Cyprus, Thailand, Turkey, Malta, Maldives, Zanzibar, and Egypt. Russian citizens might not fear a sharp rise in airplane ticket prices, as during the spring and upcoming summer seasons costs are being determined, among other factors, by demand and purchasing power.

Many Russian tourists stranded due to economic sanctions, handicapped by bank withdrawals using international credit card system. Zarina Doguzova at the Russian Federal Agency for Tourism told the local Russian media that nearly 90,000 tourists were repatriated in March.

According to the agency, Egypt has the largest number of packaged tourists from Russia. The repatriation process has been hampered and takes more time due to new Western sanctions targeting the planes expected to be used for special flights from Egypt to Russia. The tour operators struggled to bring back Russian packaged tourists by using different ways, including connecting flights of foreign airlines through third countries from the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, the Maldives and Thailand.

On April 4, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin announced that from April 9, Russia would cancel restrictions on flights to 52 countries imposed due to the pandemic, including Argentina, India, China, South Africa, and other friendly countries. It applies to regular and charter flights between Russia and several other foreign countries.

It will take into account the epidemiological situation in individual countries: a previous decision was made to completely lift restrictions on regular and charter flights with Algeria, Argentina, Afghanistan, Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Venezuela, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Egypt and Zimbabwe.

The rest include Israel, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Iraq, Kenya, China, North Korea, Costa Rica, Kuwait, Lebanon, Lesotho, Mauritius, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Morocco, Mozambique, Moldova, Mongolia, Myanmar, Namibia, Oman, Pakistan, Peru, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Serbia, Syria, Thailand, Tanzania, Tunisia, Turkey, Uruguay, Fiji, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Jamaica.

The protracted Ukraine war threatens several tourist destinations that rely on Russian visitors. Turkey, Uzbekistan, the UAE, Tajikistan, Armenia, Greece, Egypt, Kazakhstan, and Cyprus are among the top 25 countries for outbound Russian tourism by flight capacity, according to Mabrian Technologies, an intelligence platform for the tourism industry.

For instance, Egypt’s economy relies heavily on tourism from Russia and Ukraine, with the two countries accounting for roughly one-third of all visitors each year. Egypt is working to open tourism markets, particularly for Germany, England, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Switzerland, following the lifting of travel restrictions to Egypt.

Thousands of Russian tourists visit Thailand’s beach resorts. The Russia-Ukraine crisis with Europe might further push Russian tourists for popular destinations in Asia and a few destinations in Africa. While Covid-19 restrictions have been lifted, not all these countries are considered as popular destinations for Russian tourists. Russia is looking to develop and promote domestic tourism.

According to statistics, Russian tourists spent over $300 billion abroad over the past 20 years, and their money could build domestic tourism infrastructure. Experts also argue that the Russian tourism infrastructure has been demonstrating some growth over the past year, and it is important not to lose this pace under the current circumstances in the world.

Federal Agency for Tourism, which promotes tours both domestic and foreign, underscored steps being taken by the Russian government to put tourism on track including subsidy offers for local destinations, an effort towards encouraging and promoting domestic tourism, which are safe and have comfortable conditions for Russian tourists, during the forthcoming seasons.

Russian government’s latest package of measures to support the economy in the face of sanctions will address the tourism industry and a number of other sectors, and it provides for tax incentives, Federation Council Deputy Speaker Nikolai Zhuravlev said this month.

According to the Association of Tour Operators of Russia (ATOR), external tourism will steadily pick up despite the current international situation and the rising dollar and euro exchange rates, and the decline in the share of foreign tours in the volume of sales during February and March, during the months of the Russia-Ukraine crisis.

Russia’s membership has been stripped off international organizations, the latest was the United Nations Human Rights Council. On March 8, the Executive Council proposed holding an extraordinary assembly to consider a possible suspension of Russia’s membership from the United Nations World Tourism Organization.

- ← Former Myanmar Army Officer Says Rohingya Crackdown Is ‘Genocide,’ Offers To Testify – Interview

- Heroic Ukrainian Resistance To Russian Aggression Giving Rise To New World – OpEd →

Kester Kenn Klomegah

Kester Kenn Klomegah is an independent researcher and a policy consultant on African affairs in the Russian Federation and Eurasian Union. He has won media awards for highlighting economic diplomacy in the region with Africa. Currently, Klomegah is a Special Representative for Africa on the Board of the Russian Trade and Economic Development Council. He enjoys travelling and visiting historical places in Eastern and Central Europe. Klomegah is a frequent and passionate contributor to Eurasia Review.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Russian tourism in Crimea is down, but many still shrug off risks

- Medium Text

- This content was produced in Russian-annexed Crimea, where the law restricts coverage of Russian military operations in Ukraine.

'NEW CHALLENGES'

Fatal crossing.

Sign up here.

Reporting by Reuters; Writing by Mark Trevelyan and Alexander Marrow; Editing by Gareth Jones and Sharon Singleton

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

U.S. Staff Sergeant Gordon Black was detained on May 2 by police in the Russian far eastern city of Vladivostok on suspicion of stealing from a woman he was in a relationship with.

World Chevron

What protests against Israel are planned for Eurovision in Sweden?

The world's biggest live music event, the Eurovision Song Contest, is taking place in Sweden this week with 37 participating countries.

- Publishing Policies

- For Organizers/Editors

- For Authors

- For Peer Reviewers

Regional Tourism Development In Russia

The regional domestic development tourism in Russia is critical today due to ongoing geopolitical, economic, and epidemiological events. Using the existing tourism potential, diversifying the regional economies through the development of tourism and related industries are the near future tasks for regional politics. It is necessary to systematize the national tourism development factors in the regions and analyze their impact on tourist flows, which is the purpose of this work. The authors study the existing scientific background in the field of research on the factors for national tourism development in the regions, identify and systematize the factors of national tourism development, and propose a system of indicators for domestic tourism analysis. As a result of the study, regression models of factors affecting tourist flows in Russian regions were developed. The paper uses statistical analysis methods. The information base of the study is statistical sample in the regional context of the Federal Statistics Service of Russia, data from portals devoted to the tourism development in the Russian Federation, data from the rating agency "Expert" on the investment attractiveness of Russian regions. As a result, a multidimensional grouping was carried out by the analytical hierarchy method; four models developed for the entire sample and three groups of regions. The specific factors influencing the development of regional tourism in Russia in various regions are highlighted. Recommendations for the development of regional tourism are formulated based on the developed models. Keywords:

Introduction

According to Rostourism estimates, the Russian tourism industry has suffered losses of about 1.5 trillion rubles due to the pandemic; this is one of the most affected industries. It is important to note that such a sharp decline could be a chance for national tourism development in our country if the Government manages to develop effective mechanisms to support the industry and redirect tourist flows into the country. This requires serious, careful work to identify the potential and domestic tourism development factors in the regions. Many countries recovering from the coronavirus epidemic are currently developing tools to support domestic tourism (for example, subsidizing travel tickets to domestic tourist destinations - the experience of Japan and Kazakhstan). The purpose of this article is to investigate the factors of national tourism development in the regions of Russia and to build a correlation-regression model describing the influence of these factors on tourist flows in the regions. The development of tourism in many potentially ready-made regions will diversify regional economies, improve their image and attractiveness, including investment, and it would stop the "flight" of capital and human resources from the regions. Therefore, in our opinion, this topic is extremely relevant today.

Despite the great interest of scientists in the problems of tourism development in Russia and abroad, the factors of tourism development, in our opinion, remain unexplored. Kolpakidi ( 2015 ) explores institutional mechanisms (programs to support small businesses in tourism) on the example of the Irkutsk region. Adashova ( 2016 ) studies the creative potential of young people as a factor of tourism development because they are actively involved in volunteer activities and help create certain tourist brands. Kuzmina and Pegushina ( 2019 ) conducted a comprehensive analysis of the factors of the development of environmental and ethnographic tourism in the Republic of Crimea. Kirillova and Chernukha ( 2017 ) analyze the state of tourism in Russia and the Republic of Bashkiria, and the authors revealed a tendency to increase national and inbound tourism flows both at the macro level and the regional level. These researchers identify infrastructure, institutional, resource, environmental, and image factors that hinder tourism development. Fidorenko ( 2016 ) gives a more complex classification when analyzing the tourism development factors in rural regions. The author identifies two factors: first-order factors (static, natural-climatic, and cultural-historical) and second-order factors (institutional, economic, personnel, socio-demographic). Many researchers study the impact of major sporting events on the regional economy in the economic literature. Scandizzo and Pierleoni ( 2018 ) examines the impact of the Olympic Games on the economy of the regions, including aspects of sustainable economic development. Swart et al. ( 2018 ) explores the experience of holding the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. The authors propose a model for tourism development, which allows assessing the likelihood of repeated visits to Rio de Janeiro by football fans. The model includes such factors of tourist satisfaction as information support, the image of the territory, and criminal risks. The authors conclude that careful marketing creation and promotion of the territory's brand are the most critical factors. Meurer and Lins ( 2018 ) also explore the impact of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games on Brazil's tourism and economic development. They revealed an increase in tourist inflows of about 50% during the World Cup for two months, and 28% during the month during the Olympics, although they note that these effects are short-term. Gil-Alana et al. ( 2019 ) analyze the impact of the London Olympic Games, Brazil World Cup, and Rio Olympic Games on the regional economic growth. Castanho et al. ( 2020 ) investigate factors attracting tourists in the Azores. These are primarily hotels (54.7%) and nature (51.9%); culture (15%) and service quality (17.9%) became the least influential factors. Scandizzo and Pierleoni ( 2018 ) study the influence of the Olympic Games on the regional economy, including sustainable economic development aspects. Silova et al. ( 2020 ) study the impact the FIFA World Cup held in 11 Russian regions in 2018 on regional economies. Zhang et al. ( 2020 ) show the importance of measures to support tourism by the municipal Government using the example of Taiwan entrepreneurs engaged in the tourism sector. Liu et al. ( 2020 ) analyzed the problem of tourism regulation on China's example and revealed the institutional factors of tourism development. The authors highlighted five critical aspects of institutional regulation: truthful informing tourists, regulating the rules, supporting tourists, and fulfilling contracts with them, processing reviews left by tourists, feedback. Thus, researchers devote their works to individual regions or individual areas when considering tourism development problems, but there is no comprehensive analysis of the regional tourism development factors Chen et al. ( 2020 ) researched different aspects of China’s tourism development including geography, publicity, environmental protection and others. Rosato et al. ( 2021 ) study the problem of sustainable development and tourism influence, different business models were analized.

Problem Statement

Today the search for domestic economic development factors that can improve the quality of people’s lives and increase economic well-being, develop and diversify regional economies, as well as reduce the impact of external sanctions and the consequences of the 2020 pandemic, which led to severe crisis phenomena in many sectors of the economy, becomes essential. The tourism industry was severely affected in 2020, but at the same time, as the results of the tourism season of 2020 showed, the southern regions of Russia experienced a real boom in domestic tourism. The potential of domestic tourism in many regions of Russia is enormous but underestimated. For national tourism clusters, today there is a window of opportunity that should be used for advanced development, to strengthen and develop domestic tourism. That will attract additional investment in the regions, increase the standard of living of people in the regions, solve many structural economic problems. The Government considers the promotion of tourism to be an important measure of economic development at the regional level. This requires a scientific understanding of the factors that lead to changes in tourist flows, the construction of relevant analytical models, a scientifically based forecast of specific measures implementation aimed at the development of domestic tourism. The creation of a quality institutional environment as a formal institutional framework in which participants in relevant economic processes can act as conveniently as possible and the development of informal institutions associated with sustainable changes in culture and business practices should also be an essential element of regional economic policy.

Research Questions

The study raised and resolved questions: what factors affect the national tourism development in Russia, what the nature of these factors influence is, and how similar these factors are for all Russian regions. The authors analyze the following factors as initial test factors:

1. The readiness of regional residents to travel outside the region (indirectly characterizes the reluctance to relax in the region);

2. Investment attractiveness of the region (indirectly characterizes the degree of economic development);

3. Degree of tourism development in the region as assessed by relevant institutions

4. Average per capita income (indirectly characterizing economic well-being in the region);

5. The cost of arriving in the region's capital from Moscow (the higher, the less attractive it is for tourists).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the article is to analyze the domestic tourism development factors in the Russian regions, using regression analysis methods and systematized data on tourist flows and development of Russian regions in 2018.

Research Methods

The authors used statistical data collection methods, cluster analysis methods, and regression analysis methods. The logic of the study is described in five stages:

1. Forming a sample for analysis: collecting data on the number of tourists who visited each region and the main factors that can affect this indicator. The clue indicators are the number of residents leaving the region on tourist trips to Russia and abroad, the average per capita income in the region, rating of tourist attractiveness of the region, rating of investment attractiveness of the region, cost of a ticket from the regional capital to Moscow. Indicators reflecting tourist flows are given in relative form by dividing by the number of inhabitants;

2. Clearing the sample of incomplete data (missing data) and emissions (outliers) - regions in which the values of the indicators under consideration do not fit into the logic of all-Russian trends (such as Moscow, Krasnodar Territory);

3. Multidimensional grouping by cluster analysis, identification of groups of regions homogeneous in terms of selected indicators;

4. Developing and evaluation of linear regression model parameters for the whole sample and each group, comparison of results, identification of excess and harmful variables;

5. Calculation of refined models for each group, comparison, and interpretation of results.

The study is based on statistical data provided by the Federal Statistics Service of the Russian Federation on the number of tourists who visited the regions of Russia in 2018 (the resulting indicator). In the study, the authors used the following indicators: the population of the region, average per capita income in the region; these indicators are provided by the Federal Statistics Service of the Russian Federation. The authors also use the rating of tourist attractiveness of the region, calculated by the Center for Information Communications "Rating" and the magazine "Rest in Russia." This rating takes into account such components as the level of the hotel business and infrastructure development; the significance and profitability of the tourism industry in the region's economy; the region’s popularity among tourists; the region’s popularity among foreigners; tourism uniqueness; crime rate; interest in the region on the Internet; promotion of the region's tourism potential in the information space. For estimation of the regional economic development, we used the rating of investment attractiveness provided by rating agency ExpertRA. Also, the authors use the number of tourists from among the population of the region who went on tours in Russia and on foreign tours (the data provided by Federal Statistics Service); ticket price (mainly avia) from the capital of the region to Moscow (the data is provided by Aeroflot company’s site).

Data design

The calculations were made using open source software Wessa.net (Wessa, P., ( 2017 ), Agglomerative Nesting (v1.0.5) in Free Statistics Software (v1.2.1), Office for Research Development and Education, URL https://www.wessa.net/rwasp_agglomerativehierarchicalclustering.wasp/) . At this stage, data were collected for analysis, cleared of incomplete data, and emissions. As a result, 66 out of 85 Russian regions were suitable for analysis. Some regions did not provide complete data; other regions were excluded as outliers. As a result, a table was formed, including one explained variable (Y) and six explaining variables (X1... X6). A fragment of the table for regional data from the Central Federal District is given in Table 1 .

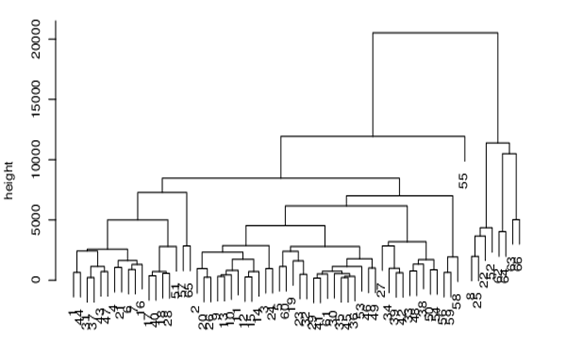

Hierarchical clustering

On the next stage, the authors compute the agglomerative nesting (hierarchical clustering) of a multivariate dataset, as proposed by Kaufman and Rousseeuw. At each level, the two nearest clusters are merged to form the next cluster using the Euclidean metric. This procedure computes the 'agglomerative coefficient,' which can be interpreted as the amount of clustering structure that has been found. Results of calculations presented on the figure 1

After this procedure, three types of regions with similar values of tourism development factors are defined; the results are presented in table 2 . Four regions (Republic of Tuva, Altai territory, Irkutsk and Kemerovo regions), which indicators significantly differ from others, are excluded for the following analysis.

The first group of regions is relatively close to Moscow, except for a few (Arkhangelsk, Amur regions), as evidenced by the relatively moderate price of a flight to the capital. The highest tourist attractiveness ratings distinguish the first group of regions, but their investment attractiveness is more than twice lower than that of the second group. We can say that these are the regions with the highest tourist potential. The second group of regions has the highest share of tourists relative to the population - almost 90%. The second group included regions from a variety of federal districts, but mainly from Central Russia. The price of air tickets to Moscow in this group is minimal. Nevertheless, this group has the lowest index of tourist attractiveness

The development of business tourism characterizes the second group's regions since they have the highest rating of investment attractiveness. These are the leading regions in the field of tourism, but it is necessary to develop the tourist image. The regions of the third group are quite far from the center, except for the Moscow region. This explains the highest price of air tickets. At the same time, these regions have high tourist attractiveness (due to unique attractions), but moderate investment attractiveness. In the third type of regions, in our opinion, it is necessary to develop infrastructure, make the region more accessible for extensive tourism. In the next step, linear regression models are constructed for each group of regions and the entire sample using the least-squares method.

Source models evaluation

The following formulae (1) to (4) show the calculated regression models for the entire sample of regions and each of the selected three groups, respectively. The description of variables X 1 - X 6 corresponds to Table 1 .

Y = - 0 . 31 + 16 . 0 ∙ X 1 + 3 . 24 ∙ X 2 + 0 . 015 ∙ X 3 + 0 . 011 ∙ X 4 - 0 . 0123 ∙ X 5 - 0 . 0511 ∙ X 6 0 . 24 2 . 41 0 . 38 1 . 39 1 . 05 0 . 51 0 . 94 (1)

Y 1 = - 4 . 91 + 23 . 6 ∙ X 1 - 48 . 3 ∙ X 2 - 0 . 0024 ∙ X 3 - 0 . 0095 ∙ X 4 + 0 . 214 ∙ X 5 + 0 . 0527 ∙ X 6 1 . 57 2 . 38 2 . 97 0 . 09 0 . 40 2 . 29 0 . 65 (2)

Y 2 = 0 . 31 + 33 . 7 ∙ X 1 + 0 . 18 ∙ X 2 + 0 . 0012 ∙ X 3 + 0 . 0105 ∙ X 4 - 0 . 00339 ∙ X 5 - 0 . 147 ∙ X 6 0 . 15 2 . 55 0 . 01 0 . 10 0 . 86 0 . 056 1 . 89 (3) Y 3 = - 2 . 42 - 4 . 35 ∙ X 1 + 2 . 14 ∙ X 2 + 0 . 011 ∙ X 3 - 0 . 0014 ∙ X 4 - 0 . 0695 ∙ X 5 - 0 . 0291 ∙ X 6 1 . 35 0 . 60 0 . 32 0 . 80 1 . 185 1 . 45 0 . 55 (4)

Normalized R-squared for basic model is 0.173, for group models – 0.375, 0.220, 0.694 respectively. This means that the distribution of regions into three groups made it possible to form qualitatively homogeneous groups. The influence of factors on regional tourism development has its special character in each. As can be seen from the given values of t-statistics for coefficients, different factors have a statistically significant influence in different groups of regions. In the next step, we exclude the variables which were not statistically significant from the models for the groups of regions.

Models enhancements

For the first group of regions, X 1 , X 2 , X 5 are recognized as statistically significant factors. The number of tourists in these regions was significantly influenced by the share of tourists traveling from the region in Russia (X 1 ) and abroad (X 2 ), as well as the size of the average per capita income of the residents of the region (X 5 ). A model built on three significant factors showed that X 1 and X 5 have a positive effect, and X 2 - a negative:

Y 1 = - 4 . 55 + 19 . 4 ∙ X 1 - 44 . 2 ∙ X 2 + 0 . 197 ∙ X 5 1 . 95 3 . 27 3 . 39 2 . 51 (5)

Normalized R-squared is 0.467, and F-statistics is 5.96. This means that the model is high-quality and corresponds well to the source data.

The number of tourists in the regions of the second group was significantly influenced by the share of tourists traveling from the region to Russia (X 1 ), as well as the investment attractiveness of the region (X 4 ) and the ticket price from the regional capital to Moscow (X 6 ). A model built on three significant factors showed that X 1 and X 4 have a positive effect, and X 6 - a negative:

Y 2 = 0 . 31 + 34 . 2 ∙ X 1 + 0 . 0099 ∙ X 4 - 0 . 145 ∙ X 6 0 . 56 3 . 41 1 . 29 2 . 14 (6)