The most distant human-made object

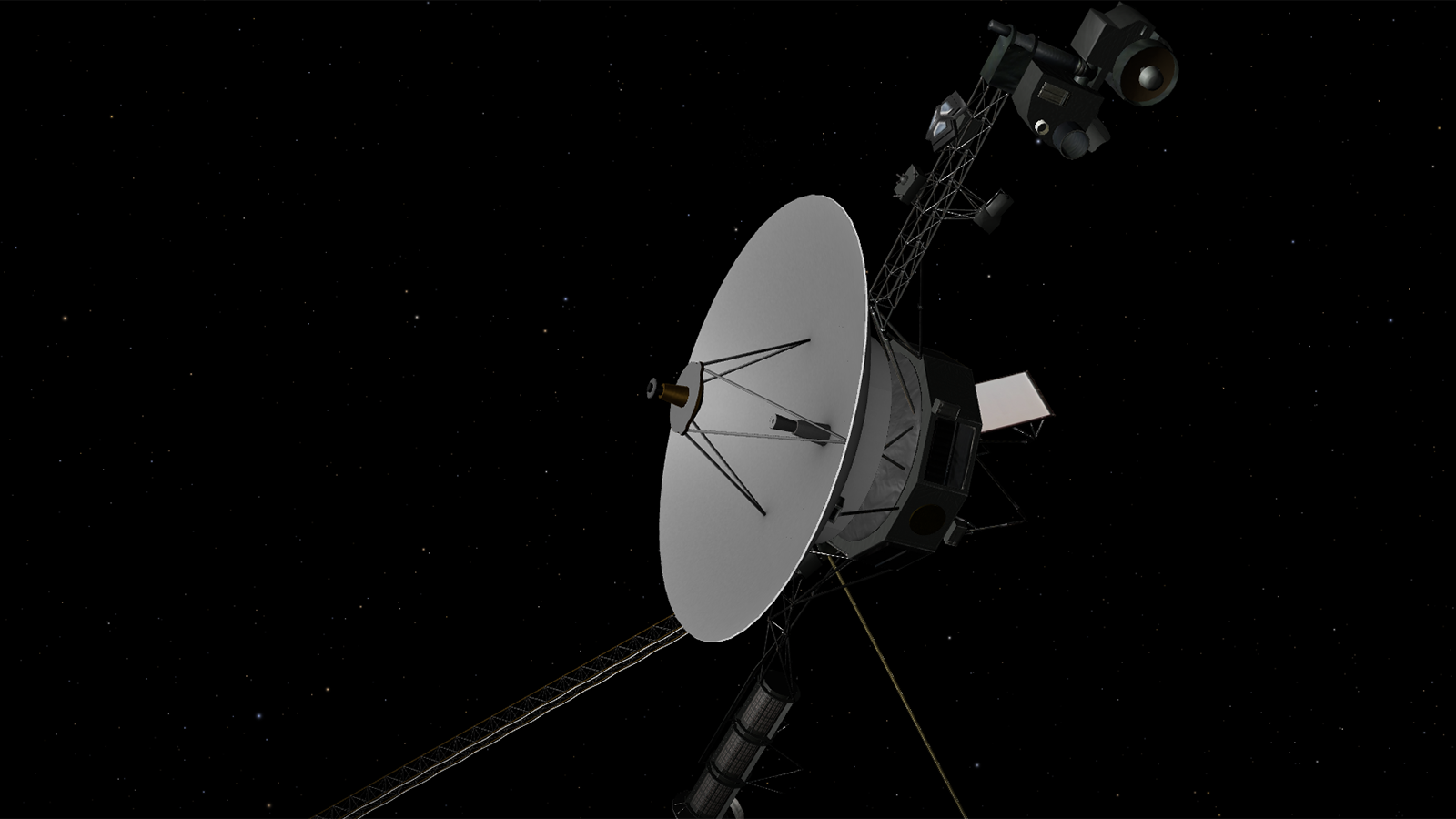

No spacecraft has gone farther than NASA's Voyager 1. Launched in 1977 to fly by Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012 and continues to collect data.

Mission Type

What is Voyager 1?

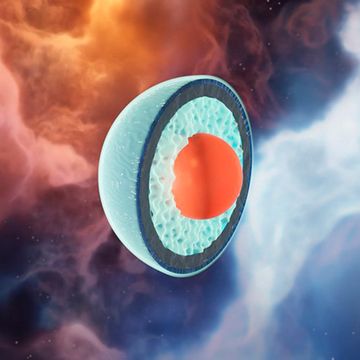

Voyager 1 has been exploring our solar system for more than 45 years. The probe is now in interstellar space, the region outside the heliopause, or the bubble of energetic particles and magnetic fields from the Sun.

- Voyager 1 was the first spacecraft to cross the heliosphere, the boundary where the influences outside our solar system are stronger than those from our Sun.

- Voyager 1 is the first human-made object to venture into interstellar space.

- Voyager 1 discovered a thin ring around Jupiter and two new Jovian moons: Thebe and Metis.

- At Saturn, Voyager 1 found five new moons and a new ring called the G-ring.

In Depth: Voyager 1

Voyager 1 was launched after Voyager 2, but because of a faster route, it exited the asteroid belt earlier than its twin, having overtaken Voyager 2 on Dec. 15, 1977.

Voyager 1 at Jupiter

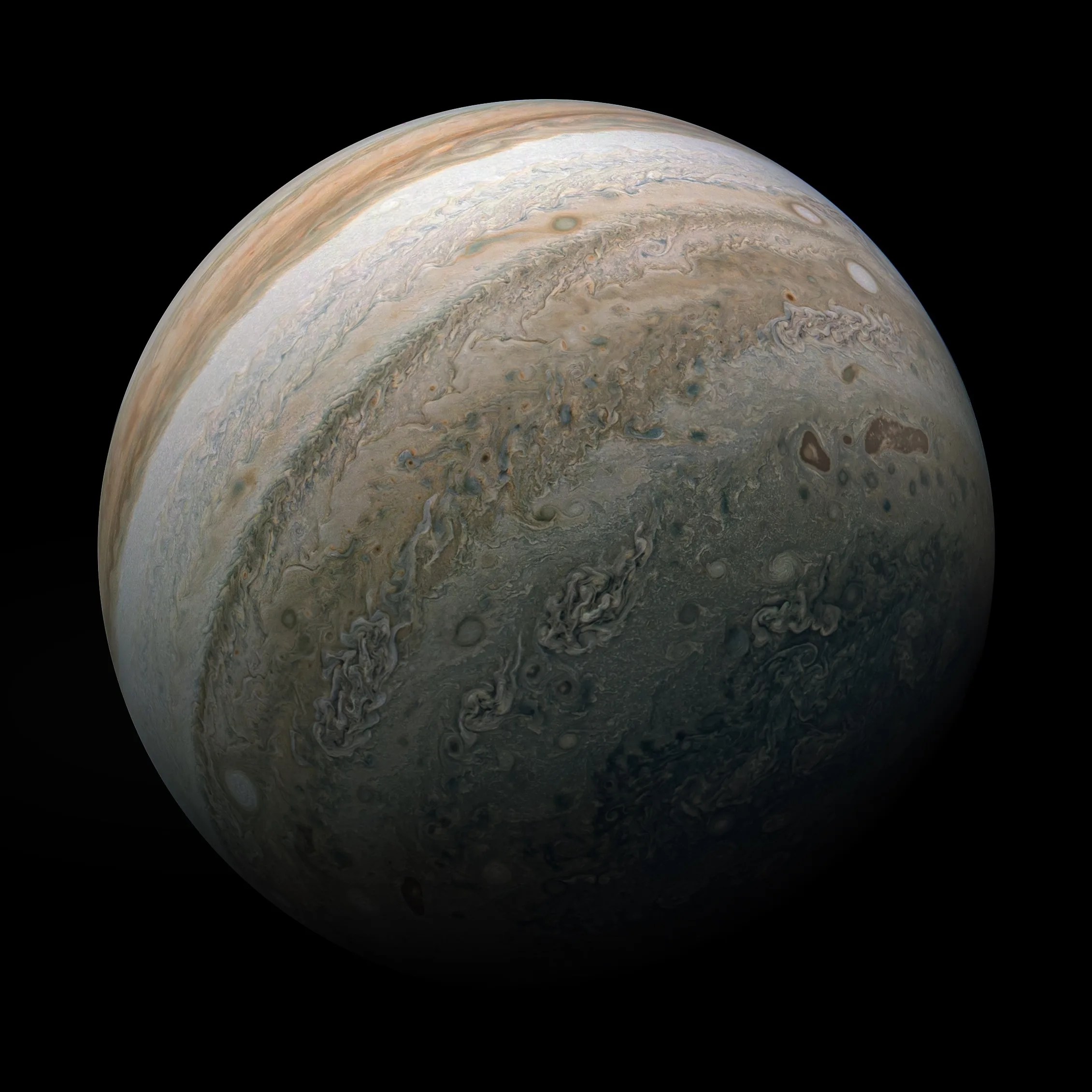

Voyager 1 began its Jovian imaging mission in April 1978 at a range of 165 million miles (265 million km) from the planet. Images sent back by January the following year indicated that Jupiter’s atmosphere was more turbulent than during the Pioneer flybys in 1973–1974.

Beginning on January 30, Voyager 1 took a picture every 96 seconds for a span of 100 hours to generate a color timelapse movie to depict 10 rotations of Jupiter. On Feb. 10, 1979, the spacecraft crossed into the Jovian moon system and by early March, it had already discovered a thin (less than 30 kilometers thick) ring circling Jupiter.

Voyager 1’s closest encounter with Jupiter was at 12:05 UT on March 5, 1979 at a range of about 174,000 miles (280,000 km). It encountered several of Jupiter’s Moons, including Amalthea, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, returning spectacular photos of their terrain, opening up completely new worlds for planetary scientists.

The most interesting find was on Io, where images showed a bizarre yellow, orange, and brown world with at least eight active volcanoes spewing material into space, making it one of the most (if not the most) geologically active planetary body in the solar system. The presence of active volcanoes suggested that the sulfur and oxygen in Jovian space may be a result of the volcanic plumes from Io which are rich in sulfur dioxide. The spacecraft also discovered two new moons, Thebe and Metis.

Voyager 1 at Saturn

Following the Jupiter encounter, Voyager 1 completed an initial course correction on April 9, 1979 in preparation for its meeting with Saturn. A second correction on Oct. 10, 1979 ensured that the spacecraft would not hit Saturn’s moon Titan.

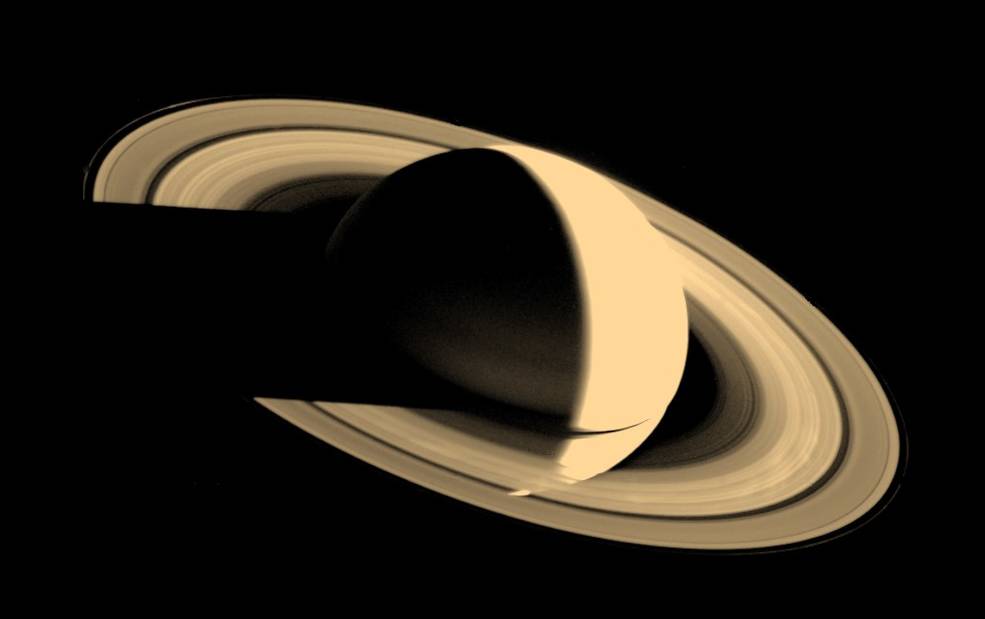

Its flyby of the Saturn system in November 1979 was as spectacular as its previous encounter. Voyager 1 found five new moons, a ring system consisting of thousands of bands, wedge-shaped transient clouds of tiny particles in the B ring that scientists called “spokes,” a new ring (the “G-ring”), and “shepherding” satellites on either side of the F-ring—satellites that keep the rings well-defined.

During its flyby, the spacecraft photographed Saturn’s moons Titan, Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea. Based on incoming data, all the moons appeared to be composed largely of water ice. Perhaps the most interesting target was Titan, which Voyager 1 passed at 05:41 UT on November 12 at a range of 2,500 miles (4,000 km). Images showed a thick atmosphere that completely hid the surface. The spacecraft found that the moon’s atmosphere was composed of 90% nitrogen. Pressure ad temperature at the surface was 1.6 atmospheres and 356 °F (–180°C), respectively.

Atmospheric data suggested that Titan might be the first body in the solar system (apart from Earth) where liquid might exist on the surface. In addition, the presence of nitrogen, methane, and more complex hydrocarbons indicated that prebiotic chemical reactions might be possible on Titan.

Voyager 1’s closest approach to Saturn was at 23:46 UT on 12 Nov. 12, 1980 at a range of 78,000 miles(126,000 km).

Voyager 1’s ‘Family Portrait’ Image

Following the encounter with Saturn, Voyager 1 headed on a trajectory escaping the solar system at a speed of about 3.5 AU per year, 35° out of the ecliptic plane to the north, in the general direction of the Sun’s motion relative to nearby stars. Because of the specific requirements for the Titan flyby, the spacecraft was not directed to Uranus and Neptune.

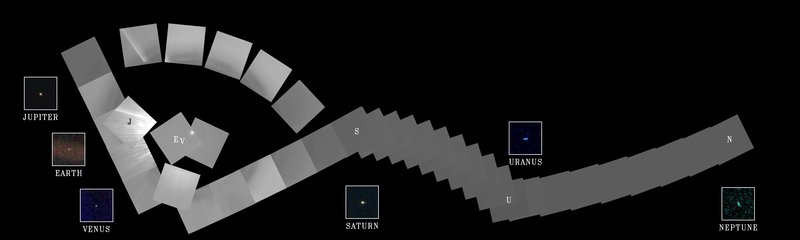

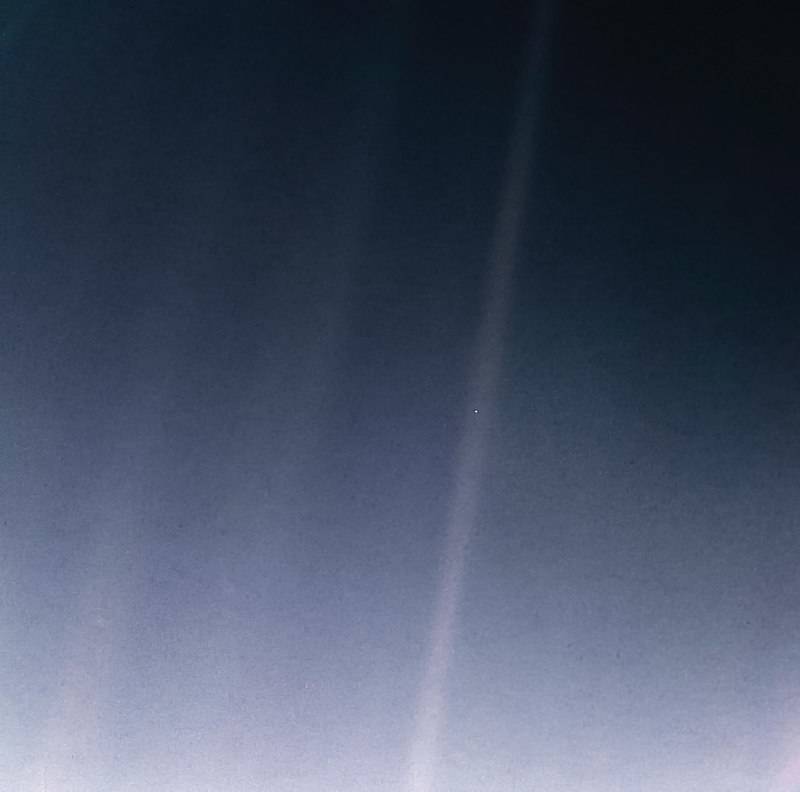

The final images taken by the Voyagers comprised a mosaic of 64 images taken by Voyager 1 on Feb. 14, 1990 at a distance of 40 AU of the Sun and all the planets of the solar system (although Mercury and Mars did not appear, the former because it was too close to the Sun and the latter because Mars was on the same side of the Sun as Voyager 1 so only its dark side faced the cameras).

This was the so-called “pale blue dot” image made famous by Cornell University professor and Voyager science team member Carl Sagan (1934-1996). These were the last of a total of 67,000 images taken by the two spacecraft.

Voyager 1’s Interstellar Mission

All the planetary encounters finally over in 1989, the missions of Voyager 1 and 2 were declared part of the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM), which officially began on Jan. 1, 1990.

The goal was to extend NASA’s exploration of the solar system beyond the neighborhood of the outer planets to the outer limits of the Sun’s sphere of influence, and “possibly beyond.” Specific goals include collecting data on the transition between the heliosphere, the region of space dominated by the Sun’s magnetic field and solar field, and the interstellar medium.

On Feb. 17, 1998, Voyager 1 became the most distant human-made object in existence when, at a distance of 69.4 AU from the Sun when it “overtook” Pioneer 10.

On Dec. 16, 2004, Voyager scientists announced that Voyager 1 had reported high values for the intensity for the magnetic field at a distance of 94 AU, indicating that it had reached the termination shock and had now entered the heliosheath.

The spacecraft finally exited the heliosphere and began measuring the interstellar environment on Aug. 25, 2012, the first spacecraft to do so.

On Sept. 5, 2017, NASA marked the 40th anniversary of its launch, as it continues to communicate with NASA’s Deep Space Network and send data back from four still-functioning instruments—the cosmic ray telescope, the low-energy charged particles experiment, the magnetometer, and the plasma waves experiment.

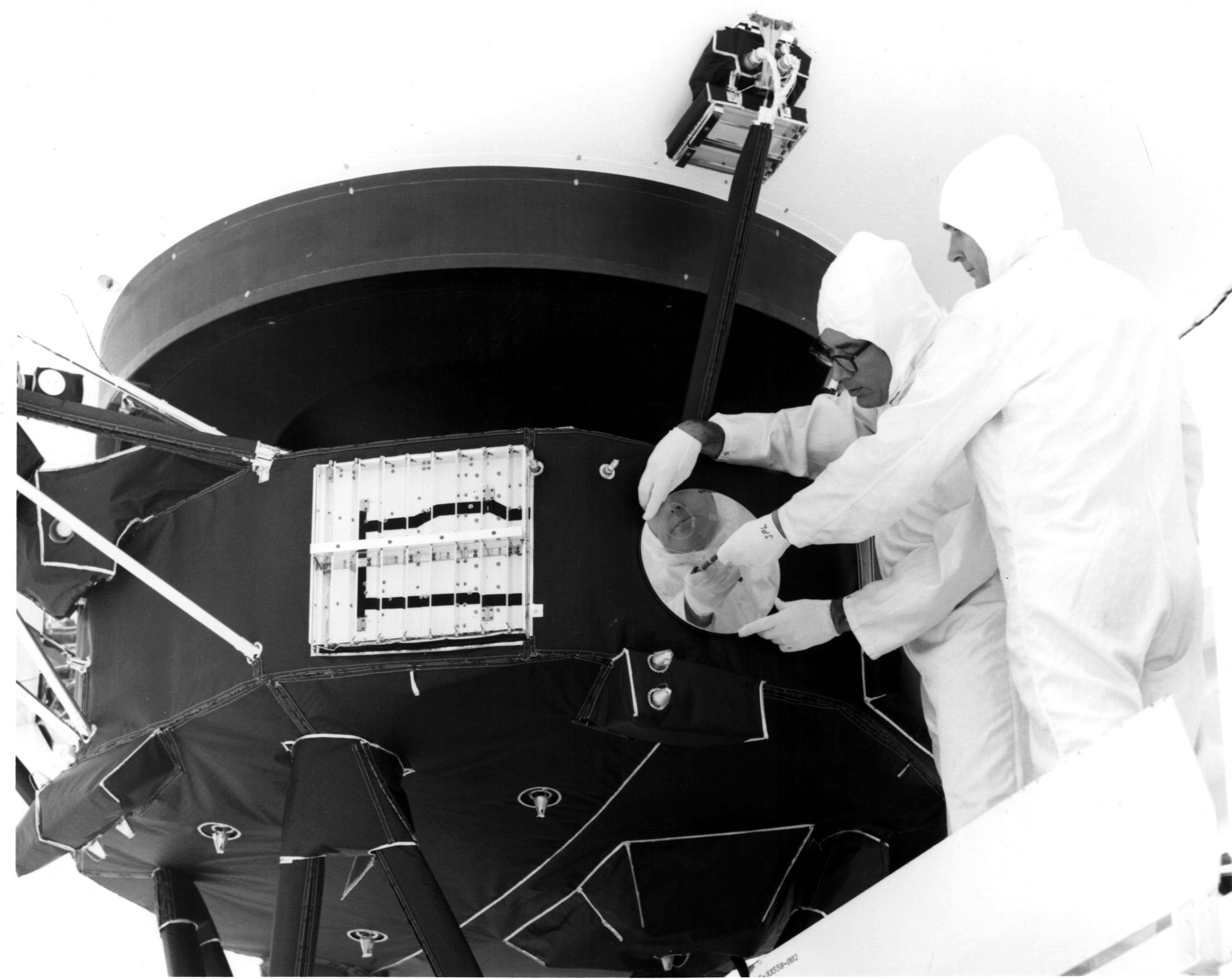

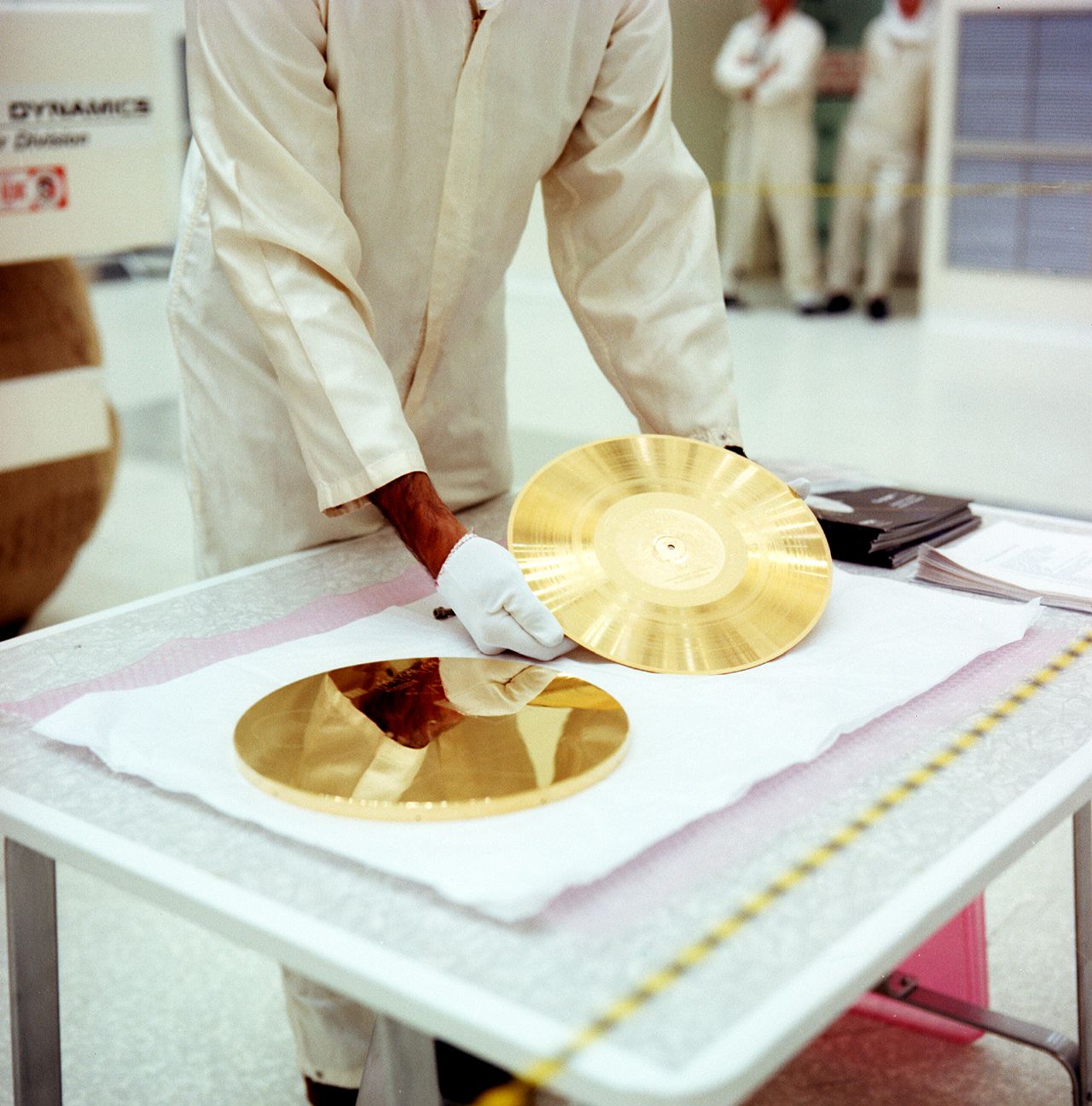

The Golden Record

Each of the Voyagers contain a “message,” prepared by a team headed by Carl Sagan, in the form of a 12-inch (30 cm) diameter gold-plated copper disc for potential extraterrestrials who might find the spacecraft. Like the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11, the record has inscribed symbols to show the location of Earth relative to several pulsars.

The records also contain instructions to play them using a cartridge and a needle, much like a vinyl record player. The audio on the disc includes greetings in 55 languages, 35 sounds from life on Earth (such as whale songs, laughter, etc.), 90 minutes of generally Western music including everything from Mozart and Bach to Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson. It also includes 115 images of life on Earth and recorded greetings from then U.S. President Jimmy Carter (1924– ) and then-UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim (1918–2007).

By January 2024, Voyager 1 was about 136 AU (15 billion miles, or 20 billion kilometers) from Earth, the farthest object created by humans, and moving at a velocity of about 38,000 mph (17.0 kilometers/second) relative to the Sun.

National Space Science Data Center: Voyager 1

A library of technical details and historic perspective.

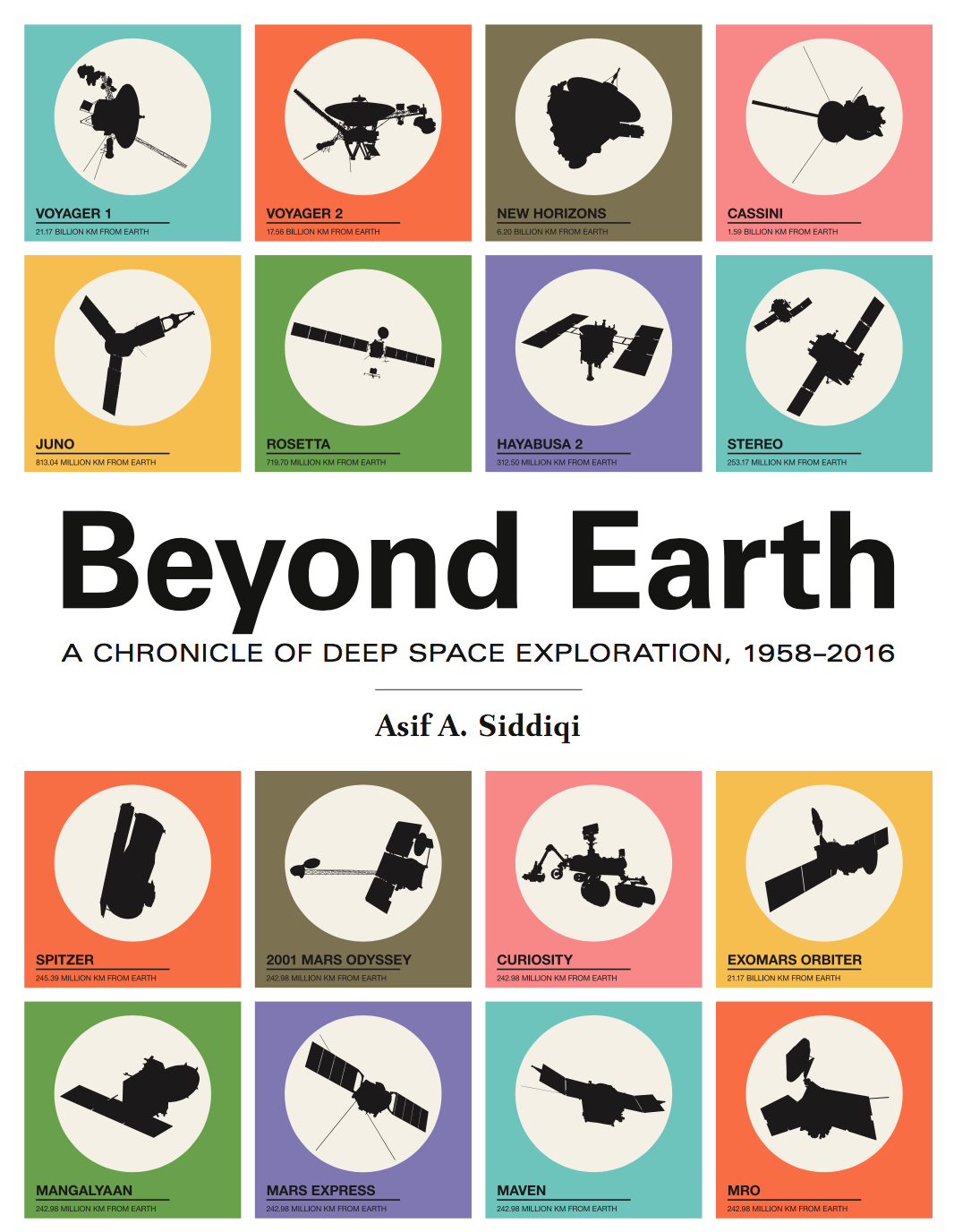

Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration

A comprehensive history of missions sent to explore beyond Earth.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

- Mobile Site

- Staff Directory

- Advertise with Ars

Filter by topic

- Biz & IT

- Gaming & Culture

Front page layout

Some hope —

Finally, engineers have a clue that could help them save voyager 1, a new signal from humanity's most distant spacecraft could be the key to restoring it..

Stephen Clark - Mar 15, 2024 11:23 pm UTC

It's been four months since NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft sent an intelligible signal back to Earth, and the problem has puzzled engineers tasked with supervising the probe exploring interstellar space.

But there's a renewed optimism among the Voyager ground team based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. On March 1, engineers sent a command up to Voyager 1—more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away from Earth—to "gently prompt" one of the spacecraft's computers to try different sequences in its software package. This was the latest step in NASA's long-distance troubleshooting to try to isolate the cause of the problem preventing Voyager 1 from transmitting coherent telemetry data.

Cracking the case

Officials suspect a piece of corrupted memory inside the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS), one of three main computers on the spacecraft, is the most likely culprit for the interruption in normal communication. Because Voyager 1 is so far away, it takes about 45 hours for engineers on the ground to know how the spacecraft reacted to their commands—the one-way light travel time is about 22.5 hours.

The FDS collects science and engineering data from the spacecraft's sensors, then combines the information into a single data package, which goes through a separate component called the Telemetry Modulation Unit to beam it back to Earth through Voyager's high-gain antenna.

Engineers are almost entirely certain the problem is in the FDS computer. The communications systems onboard Voyager 1 appear to be functioning normally, and the spacecraft is sending a steady radio tone back to Earth, but there's no usable data contained in the signal. This means engineers know Voyager 1 is alive, but they have no insight into what part of the FDS memory is causing the problem.

But Voyager 1 responded to the March 1 troubleshooting command with something different from what engineers have seen since this issue first appeared on November 14.

"The new signal was still not in the format used by Voyager 1 when the FDS is working properly, so the team wasn’t initially sure what to make of it," NASA said in an update Wednesday. "But an engineer with the agency’s Deep Space Network, which operates the radio antennas that communicate with both Voyagers and other spacecraft traveling to the Moon and beyond, was able to decode the new signal and found that it contains a readout of the entire FDS memory."

Now, engineers are meticulously comparing each bit of code from the FDS memory readout to the memory readout Voyager 1 sent back to Earth before the issue arose in November. This, they hope, will allow them to find the root of the problem. But it will probably take weeks or months for the Voyager team to take the next step. They don't want to cause more harm.

"Using that information to devise a potential solution and attempt to put it into action will take time," NASA said.

This is perhaps the most serious ailment the spacecraft has encountered since its launch in 1977. Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn before getting a kick from Saturn's gravity to speed into the outer solar system. In 2012, Voyager 1 entered interstellar space when it crossed the heliopause, where the solar wind, the stream of particles emanating from the Sun, push against a so-called galactic wind, the particles that populate the void between the stars.

Engineers have kept Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, alive for more than 46 years , overcoming technical problems that have doomed other space missions. Both probes face waning power from their nuclear batteries, and there are concerns about their thrusters aging and fuel lines becoming clogged, among other things. But each time there is a problem, ground teams have come up with a trick to keep the Voyagers going, often referencing binders of fraying blueprints and engineering documents from the spacecraft's design and construction nearly 50 years ago.

Suzanne Dodd, NASA's project manager for Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, recently told Ars that engineers would need to pull off their "biggest miracle" to restore Voyager 1 to normal operations. Now, Voyager 1's voice from the sky has provided engineers with a clue that could help them realize this miracle.

reader comments

Channel ars technica.

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

What’s Up: April 2024 Skywatching Tips from NASA

NASA VIPER Robotic Moon Rover Team Raises Its Mighty Mast

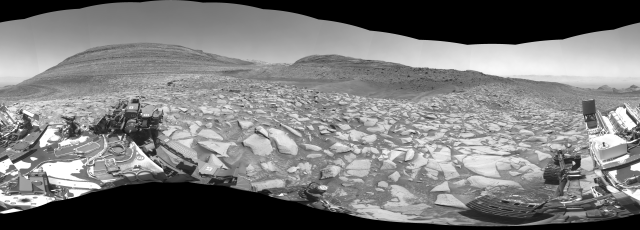

NASA’s Curiosity Searches for New Clues About Mars’ Ancient Water

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

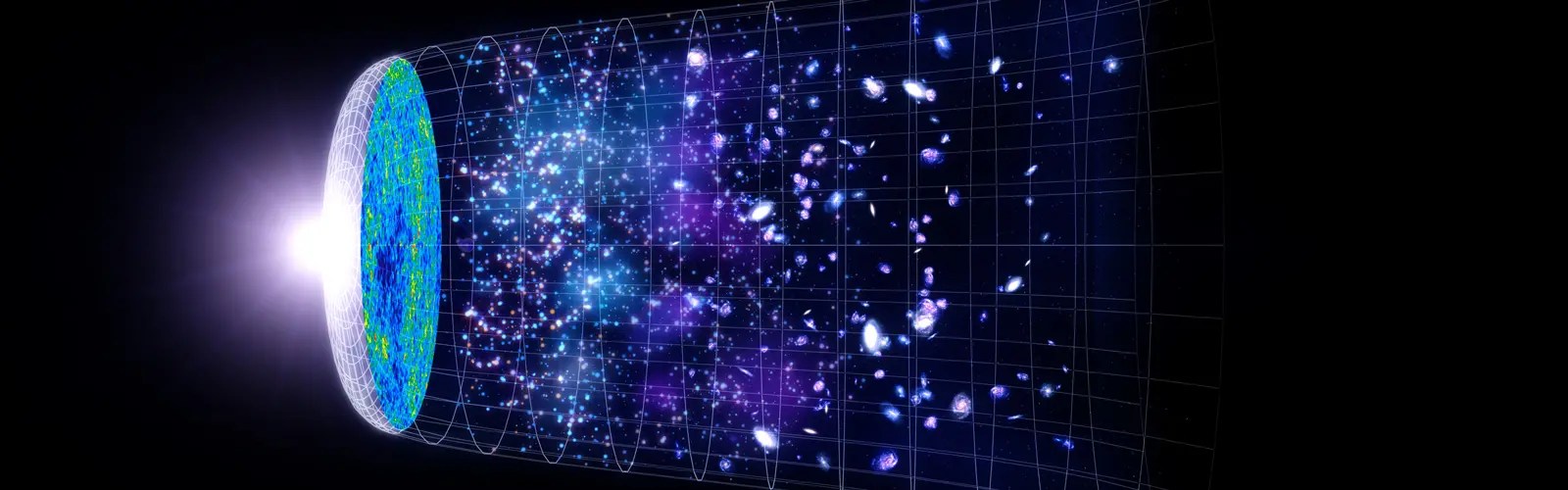

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

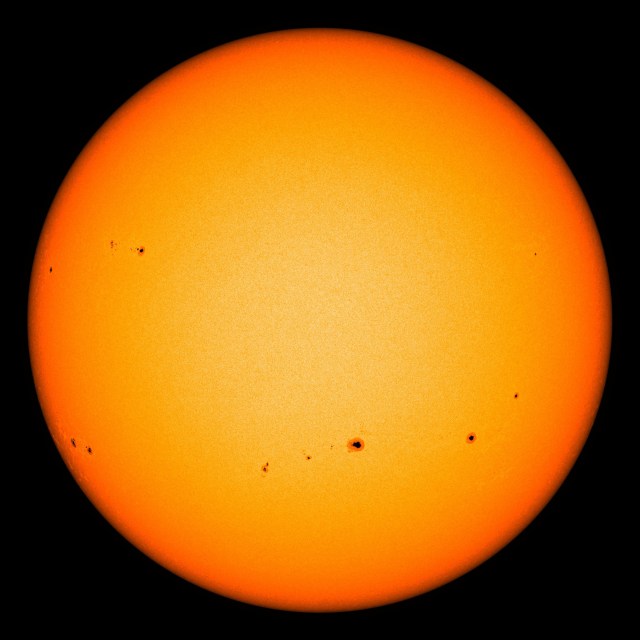

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

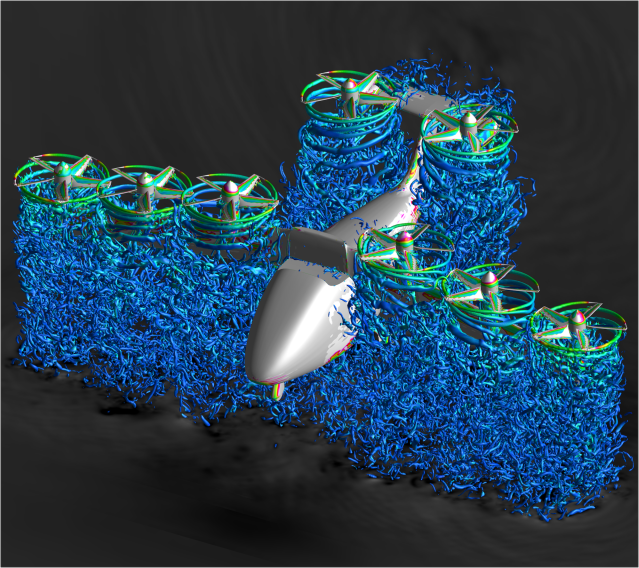

NASA Noise Prediction Tool Supports Users in Air Taxi Industry

Making of the Golden Record

NASA Wallops to Launch Three Sounding Rockets During Solar Eclipse

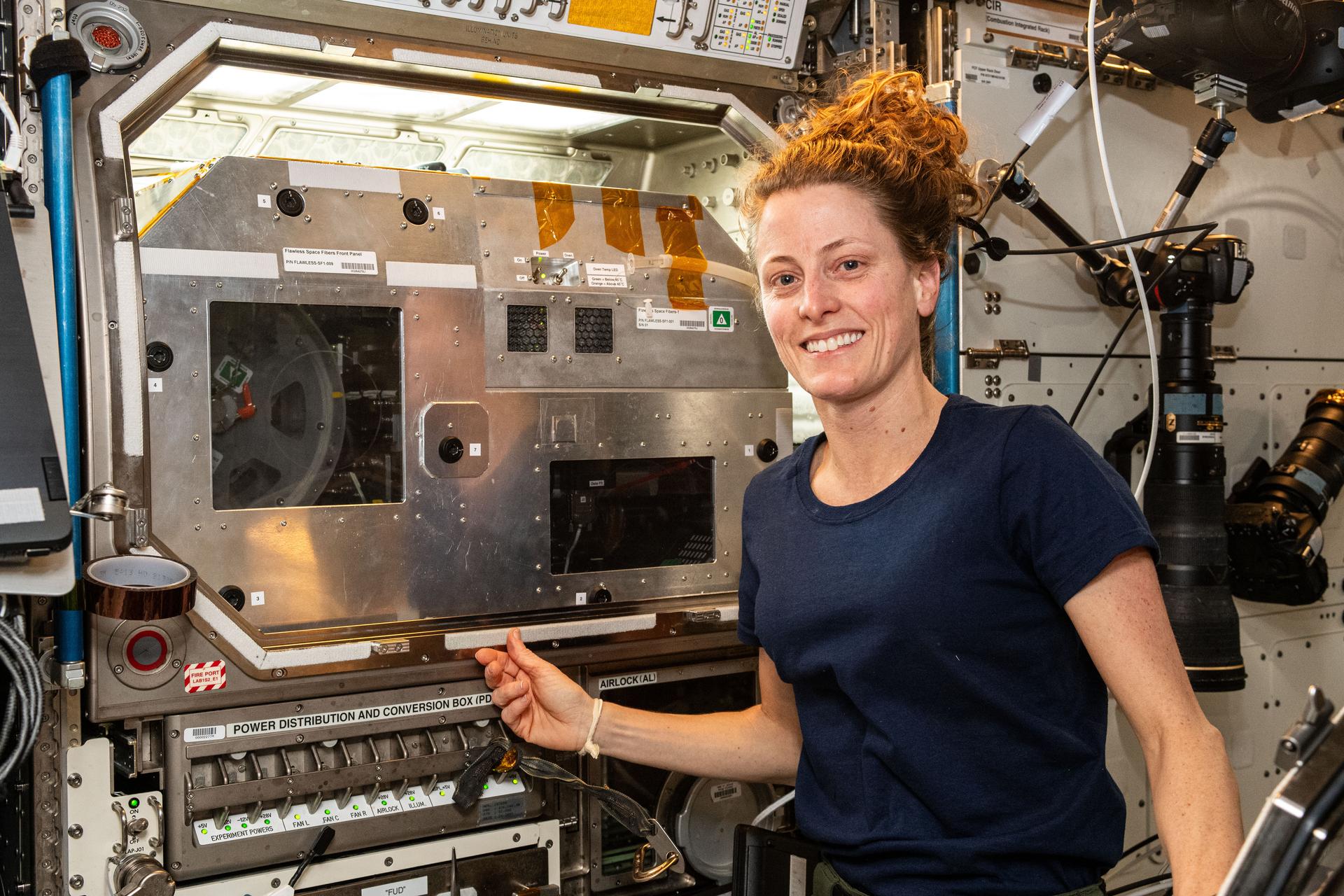

NASA Astronaut Loral O’Hara, Expedition 70 Science Highlights

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

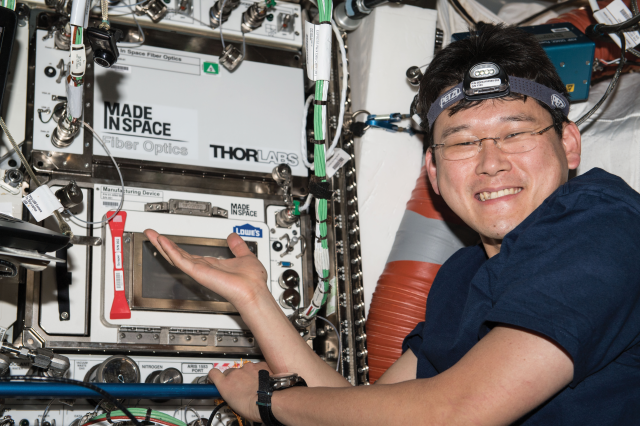

Optical Fiber Production

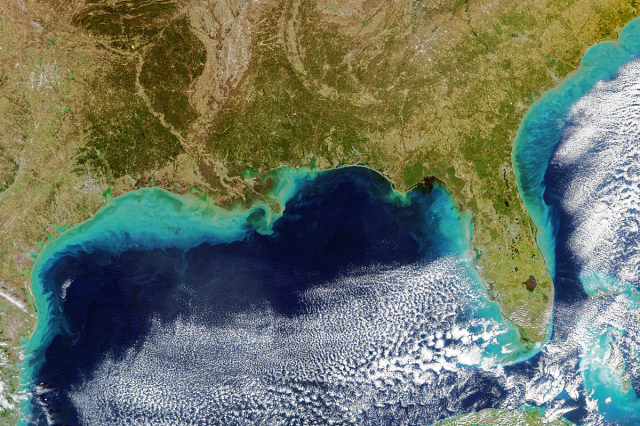

How NASA Spotted El Niño Changing the Saltiness of Coastal Waters

Earth Day Toolkit

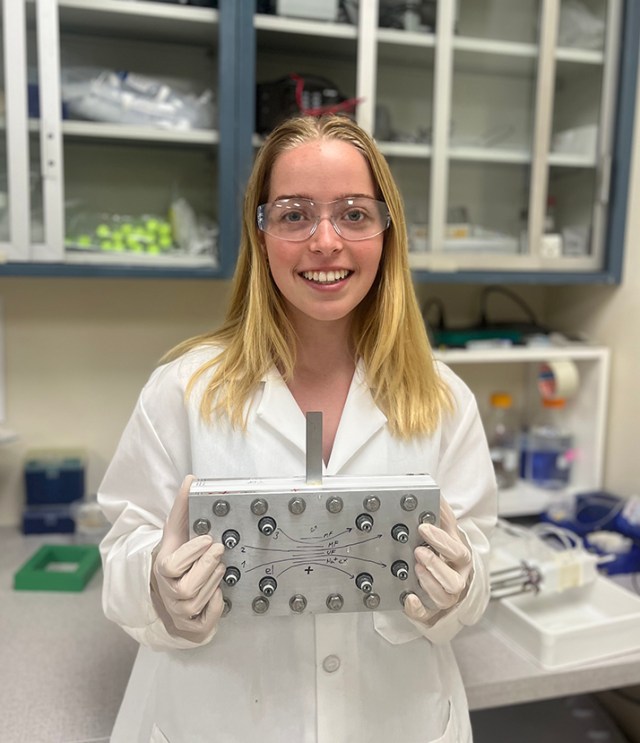

Veronica T. Pinnick Put NASA’s PACE Mission through Its Paces

Harnessing the 2024 Eclipse for Ionospheric Discovery with HamSCI

How NASA’s Roman Telescope Will Measure Ages of Stars

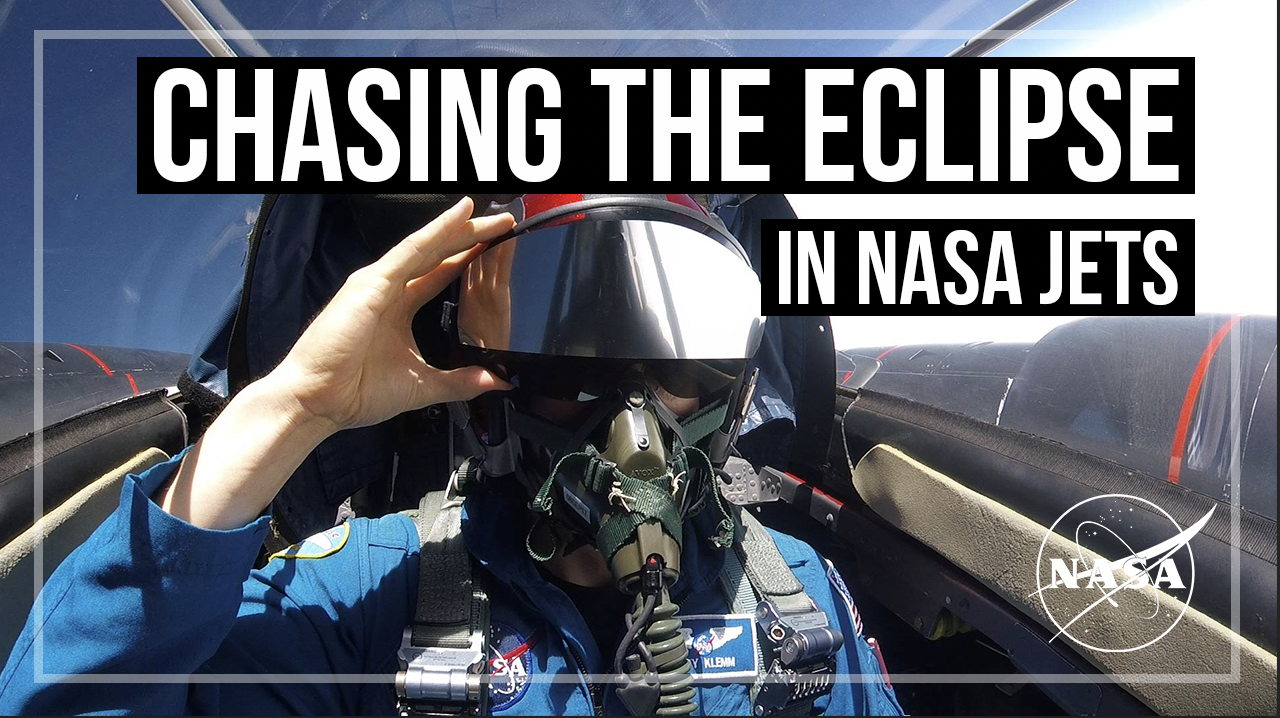

Scientists Pursue the Total Solar Eclipse with NASA Jet Planes

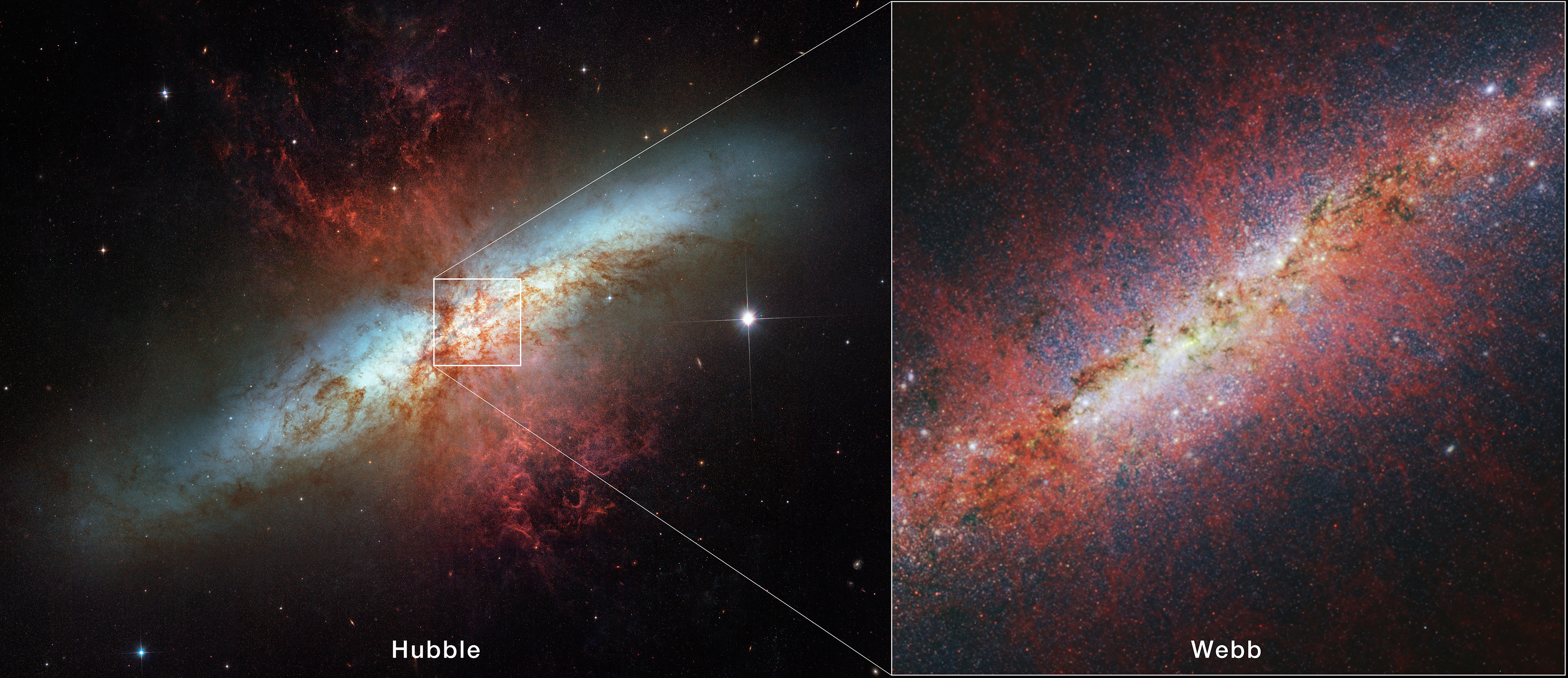

NASA’s Webb Probes an Extreme Starburst Galaxy

Universe Stories

ARMD Solicitations

F-15D Support Aircraft

Tech Today: Synthetic DNA Diagnoses COVID, Cancer

David Woerner

Tech Today: Cutting the Knee Surgery Cord

NASA Partnerships Bring 2024 Total Solar Eclipse to Everyone

NASA, Salisbury U. Enact Agreement for Workforce Development

2024 Total Solar Eclipse Broadcast

NASA Engineer Chris Lupo Receives 2024 Federal Engineer Award

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Earns Neil Armstrong Space Flight Achievement Award

Meet the Two Women Leading Space Station Science

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

45 years ago: voyager 1 begins its epic journey to the outer planets and beyond, johnson space center.

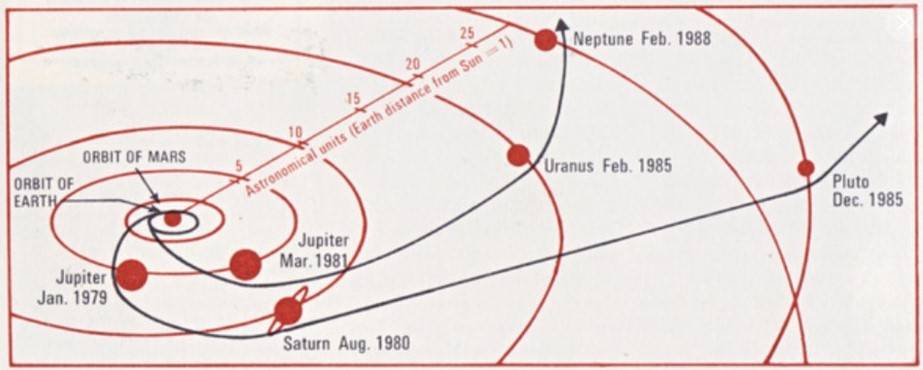

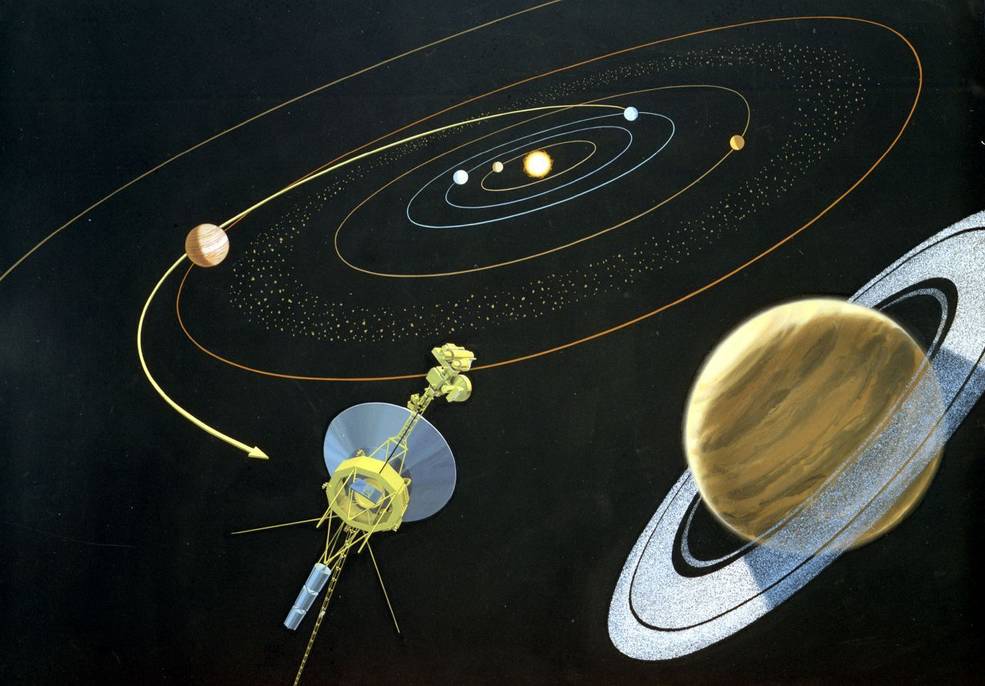

Forty-five years ago, the Voyager 1 spacecraft began an epic journey that continues to this day. The second of a pair of spacecraft, Voyager 1 lifted off on Sept. 5, 1977, 16 days after its twin left on a similar voyage. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, managed the two spacecraft on their missions to explore the outer planets. Taking advantage of a rare planetary alignment to use the gravity of one planet to redirect the spacecraft to the next, the Voyagers planned to use Jupiter’s gravity to send them on to explore Saturn and its large moon Titan. They carried sophisticated instruments to conduct their in-depth explorations of the giant planets. Both spacecraft continue to return data as they make their way out of our solar system and enter interstellar space.

In the 1960s, mission designers at JPL noted that the next occurrence of a once-every-175-year alignment of the outer planets would happen in the late 1970s. A spacecraft could take advantage of this opportunity to fly by Jupiter and use its gravity to bend its trajectory to visit Saturn, and repeat the process to also visit Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. Launching several missions to visit each planet individually would take much longer and cost much more. The original plan to send two pairs of Thermoelectric Outer Planet Spacecraft on these Grand Tours proved too costly leading to its cancellation in 1971. The next year, NASA approved a scaled-down version of the project to send a pair of Mariner-class spacecraft in 1977 to explore just Jupiter and Saturn, with an expected five-year operational life. On March 7, 1977, NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher announced the renaming of these Mariner Jupiter/Saturn 1977 spacecraft as Voyager 1 and 2. Scientists held out hope that one of them could ultimately visit Uranus and Neptune, thereby fulfilling most of the original Grand Tour’s objectives – Pluto would have to wait several decades for its first visit.

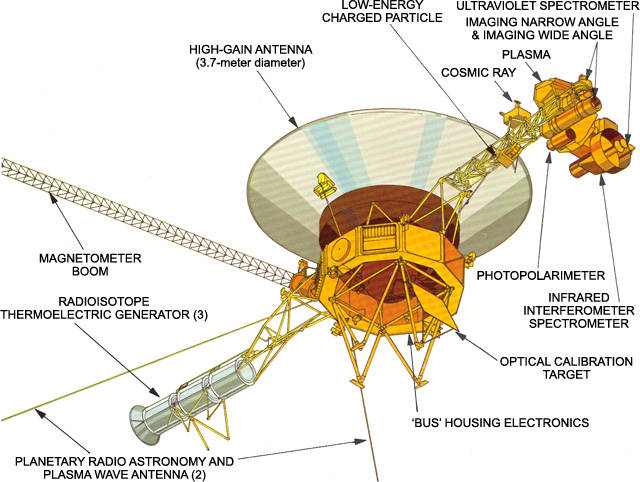

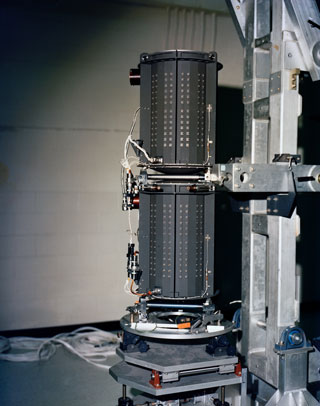

Each Voyager carried a suite of 11 instruments to study the planets during each encounter and to learn more about interplanetary space in the outer reaches of the solar system, including:

- An imaging science system consisting of narrow-angle and wide-angle cameras to photograph the planet and its satellites.

- A radio science system to determine the planet’s physical properties.

- An infrared interferometer spectrometer to investigate local and global energy balance and atmospheric composition.

- An ultraviolet spectrometer to measure atmospheric properties.

- A magnetometer to analyze the planet’s magnetic field and interaction with the solar wind.

- A plasma spectrometer to investigate microscopic properties of plasma ions.

- A low-energy charged particle device to measure fluxes and distributions of ions.

- A cosmic ray detection system to determine the origin and behavior of cosmic radiation.

- A planetary radio astronomy investigation to study radio emissions from Jupiter.

- A photopolarimeter to measure the planet’s surface composition.

- A plasma wave system to study the planet’s magnetosphere.

Voyager 1 lifted off on Sept. 5, 1977, atop a Titan IIIE-Centaur rocket from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, in Florida. Two weeks after its launch, from a distance of 7.25 million miles, Voyager 1 turned its camera back toward its home planet and took the first single-frame image of the Earth-Moon system. The spacecraft successfully crossed the asteroid belt between Dec. 10, 1977, and Sept. 8, 1978.

Although Voyager 1 launched two weeks after its twin, it traveled on a faster trajectory and arrived at Jupiter four months earlier. Voyager 1 conducted its observations of Jupiter between Jan. 6 and April 13, 1979, making its closest approach of 216,837 miles from the planet’s center on March 5. The spacecraft returned 19,000 images of the giant planet, many of Jupiter’s satellites, and confirmed the presence of a thin ring encircling it. Its other instruments returned information about Jupiter’s atmosphere and magnetic field. Jupiter’s massive gravity field bent the spacecraft’s trajectory and accelerated it toward Saturn.

Voyager 1 began its long-range observations of Saturn on Aug. 22, 1980, passed within 114,500 miles of the planet’s center on Nov. 12, and concluded its studies on Dec. 14. Because of its interest to scientists, mission planners chose the spacecraft’s trajectory to make a close flyby of Saturn’s largest moon Titan – the only planetary satellite with a dense atmosphere – just before the closest approach to the planet itself. This trajectory, passing over Saturn’s south pole and bending north over the plane of the ecliptic, precluded Voyager 1 from making any additional planetary encounters. The spacecraft flew 4,033 miles from Titan’s center, returning images of its unbroken orange atmosphere and high-altitude blue haze layer. During the encounter, Voyager 1 returned 16,000 photographs, imaging Saturn, its rings, many of its known satellites and discovering several new ones, while its instruments returned data about Saturn’s atmosphere and magnetic field.

On Feb. 14, 1990, more than 12 years after it began its journey from Earth and shortly before controllers permanently turned off its cameras to conserve power, Voyager 1 spun around and pointed them back into the solar system. In a mosaic of 60 images, it captured a “family portrait” of six of the solar system’s planets, including a pale blue dot called Earth more than 3.7 billion miles away. Fittingly, these were the last pictures returned from either Voyager spacecraft. On Feb. 17, 1998, Voyager 1 became the most distant human-made object, overtaking the Pioneer 10 spacecraft on their way out of the solar system. In February 2020, to commemorate the photograph’s 30th anniversary, NASA released a remastered version of the image of Earth as Pale Blue Dot Revisited .

On New Year’s Day 1990, both spacecraft officially began the Voyager Interstellar Mission as they inexorably made their escape from our solar system. On Aug. 25, 2012, Voyager 1 passed beyond the heliopause, the boundary between the heliosphere, the bubble-like region of space created by the Sun, and the interstellar medium. Its twin followed suit six years later. Today , 45 years after its launch and 14.6 billion miles from Earth, four of Voyager 1’s 11 instruments continue to return useful data, having now spent 10 years in interstellar space. Signals from the spacecraft take nearly 22 hours to reach Earth, and 22 hours for Earth-based signals to reach the spacecraft. Engineers expect that the spacecraft will continue to return data from interstellar space until about 2025 when it will no longer be able to power its systems. And just in case an alien intelligence finds it one day, Voyager 1 like its twin carries a gold-plated record that contains information about its home planet, including recordings of terrestrial sounds, music, and greetings in 55 languages. Engineers at NASA thoughtfully included Instructions on how to play the record.

The voyage continues…

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 10 May 2021

Persistent plasma waves in interstellar space detected by Voyager 1

- Stella Koch Ocker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4941-5333 1 ,

- James M. Cordes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4049-1882 1 ,

- Shami Chatterjee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2878-1502 1 ,

- Donald A. Gurnett ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2403-0282 2 ,

- William S. Kurth ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5471-6202 2 &

- Steven R. Spangler 2

Nature Astronomy volume 5 , pages 761–765 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2510 Accesses

20 Citations

1264 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Interstellar medium

- Space physics

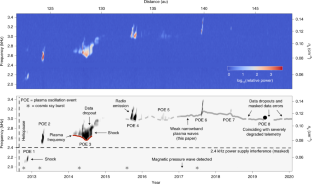

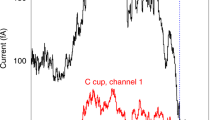

In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first in situ probe of the very local interstellar medium 1 . The Voyager 1 Plasma Wave System has given point estimates of the plasma density spanning about 30 au of interstellar space, revealing a large-scale density gradient 2 , 3 and turbulence 4 outside of the heliopause. Previous studies of the plasma density relied on the detection of discrete plasma oscillation events triggered ahead of shocks propagating outwards from the Sun, which were used to infer the plasma frequency and, hence, density 5 , 6 . We present the detection of a class of very weak, narrowband plasma wave emission in the Voyager 1 data that persists from 2017 onwards and enables a steadily sampled measurement of the interstellar plasma density over about 10 au with an average sampling distance of 0.03 au. We find au-scale density fluctuations that trace interstellar turbulence between episodes of previously detected plasma oscillations. Possible mechanisms for the narrowband emission include thermally excited plasma oscillations and quasi-thermal noise, and they could be clarified by new findings from Voyager or a future interstellar mission. The emission’s persistence suggests that Voyager 1 may be able to continue tracking the interstellar plasma density in the absence of shock-generated plasma oscillation events.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Voyager 2 plasma observations of the heliopause and interstellar medium

John D. Richardson, John W. Belcher, … Leonard F. Burlaga

Plasma densities near and beyond the heliopause from the Voyager 1 and 2 plasma wave instruments

D. A. Gurnett & W. S. Kurth

Evidence of ubiquitous Alfvén pulses transporting energy from the photosphere to the upper chromosphere

Jiajia Liu, Chris J. Nelson, … Robert Erdélyi

Data availability

The Voyager 1 data used in this work are archived through the NASA Planetary Data System ( https://doi.org/10.17189/1519903 ). Data and examples of the PWS data processing algorithms are also available through the University of Iowa Subnode of the PDS Planetary Plasma Interactions Node ( https://space.physics.uiowa.edu/voyager/data/ ).

Gurnett, D. A., Kurth, W. S., Burlaga, L. F. & Ness, N. F. In situ observations of interstellar plasma with Voyager 1. Science 341 , 1489–1492 (2013).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Gurnett, D. A. & Kurth, W. S. Plasma densities near and beyond the heliopause from the Voyager 1 and 2 plasma wave instruments. Nat. Astron. 3 , 1024–1028 (2019).

Kurth, W. S. & Gurnett, D. A. Observations of a radial density gradient in the very local interstellar medium by Voyager 2. Astrophys. J. Lett. 900 , L1 (2020).

Lee, K. H. & Lee, L. C. Interstellar turbulence spectrum from in situ observations of Voyager 1. Nat. Astron. 3 , 154–159 (2019).

Gurnett, D. A. et al. Precursors to interstellar shocks of solar origin. Astrophys. J. 809 , 121 (2015).

Gurnett, D. A. et al. A foreshock model for interstellar shocks of solar origin: Voyager 1 and 2 observations. Astron. J. 161 , 11 (2021).

Cairns, I. H. & Robinson, P. A. Theory for low-frequency modulated Langmuir wave packets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19 , 2187–2190 (1992).

Hospodarsky, G. B. et al. Fine structure of Langmuir waves observed upstream of the bow shock at Venus. J. Geophys. Res. 99 , 13363–13372 (1994).

Burlaga, L. F., Ness, N. F., Gurnett, D. A. & Kurth, W. S. Evidence for a shock in interstellar plasma: Voyager 1. Astrophys. J. Lett. 778 , L3 (2013).

Kim, T. K., Pogorelov, N. V. & Burlaga, L. F. Modeling shocks detected by Voyager 1 in the local interstellar medium. Astrophys. J. Lett. 843 , L32 (2017).

Huchra, J. P. & Geller, M. J. Groups of galaxies. I. Nearby groups. Astrophys. J. 257 , 423–437 (1982).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12 , 2825–2830 (2011).

MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Redfield, S. & Falcon, R. E. The structure of the local interstellar medium. V. Electron densities. Astrophys. J. 683 , 207–225 (2008).

Salpeter, E. E. Electron density fluctuations in a plasma. Phys. Rev. 120 , 1528–1535 (1960).

Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar

Perkins, F. & Salpeter, E. E. Enhancement of plasma density fluctuations by nonthermal electrons. Phys. Rev. 139 , 55–62 (1965).

Dougherty, J. P. & Farley, D. T. A theory of incoherent scattering of radio waves by a plasma. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 259 , 79–99 (1960).

Carlson, H. C., Wickwar, V. B. & Mantas, G. P. Observations of fluxes of suprathermal electrons accelerated by HF excited instabilities. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 44 , 1089–1100 (1982).

Vierinen, J. et al. Radar observations of thermal plasma oscillations in the ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44 , 5301–5307 (2017).

Meyer-Vernet, N., Issautier, K. & Moncuquet, M. Quasi-thermal noise spectroscopy: the art and the practice. J. Geophys. Res. 122 , 7925–7945 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Rickett, B. J. Radio propagation through the turbulent interstellar plasma. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 28 , 561–605 (1990).

Spangler, S. R. & Gwinn, C. R. Evidence for an inner scale to the density turbulence in the interstellar medium. Astrophys. J. Lett. 353 , L29 (1990).

Bhat, N. D. R., Cordes, J. M., Camilo, F., Nice, D. J. & Lorimer, D. R. Multifrequency observations of radio pulse broadening and constraints on interstellar electron density microstructure. Astrophys. J. 605 , 759–783 (2004).

Rickett, B., Johnston, S., Tomlinson, T. & Reynolds, J. The inner scale of the plasma turbulence towards PSR J1644–4559. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 395 , 1391–1402 (2009).

Lee, K. H. & Lee, L. C. Turbulence spectra of electron density and magnetic field fluctuations in the local interstellar medium. Astrophys. J. 904 , 66 (2020).

Burlaga, L. F., Florinski, V. & Ness, N. F. Turbulence in the outer heliosheath. Astrophys. J. 854 , 20 (2018).

Cordes, J. M., Weisberg, J. M., Frail, D. A., Spangler, S. R. & Ryan, M. The galactic distribution of free electrons. Nature 354 , 121–124 (1991).

Krishnakumar, M. A., Mitra, D., Naidu, A., Joshi, B. C. & Manoharan, P. K. Scatter broadening measurements of 124 pulsars at 32 Mhz. Astrophys. J. 804 , 23 (2015).

Ocker, S. K., Cordes, J. M. & Chatterjee, S. Electron density structure of the local galactic disk. Astrophys. J. 897 , 124 (2020).

Zank, G. P., Nakanotani, M. & Webb, G. M. Compressible and incompressible magnetic turbulence observed in the very local interstellar medium by Voyager 1. Astrophys. J. 887 , 116 (2019).

Fraternale, F. & Pogorelov, N. V. Waves and turbulence in the very local interstellar medium: from macroscales to microscales. Astrophys. J. 906 , 75 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

S.K.O., J.M.C., S.C. and S.R.S. acknowledge support from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA 80NSSC20K0784). S.K.O., J.M.C. and S.C. also acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (NSF AAG-1815242) and are members of the NANOGrav Physics Frontiers Center, which is supported by the NSF award PHY-1430284. The research at the University of Iowa was supported by NASA through Contract 1622510 with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Astronomy and Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Stella Koch Ocker, James M. Cordes & Shami Chatterjee

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA

Donald A. Gurnett, William S. Kurth & Steven R. Spangler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.K.O. conducted the data analysis and wrote the initial draft of the paper. J.M.C., S.C., S.R.S. and S.K.O. are NASA Outer Heliosphere Guest Investigators on the Voyager Interstellar Mission. D.A.G. is the Principal Investigator of the Voyager PWS investigation and W.S.K. is a co-investigator of Voyager PWS and was responsible for the initial processing of the data at the University of Iowa. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and commented on the draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stella Koch Ocker .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Astronomy thanks G. P. Zank and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ocker, S.K., Cordes, J.M., Chatterjee, S. et al. Persistent plasma waves in interstellar space detected by Voyager 1. Nat Astron 5 , 761–765 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01363-7

Download citation

Received : 27 January 2021

Accepted : 30 March 2021

Published : 10 May 2021

Issue Date : August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01363-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Simulation study of optical turbulence in interstellar medium by phase screens.

- Masoud Rezaee

- Yasser Rajabi

- Khodadad Kokabi

Indian Journal of Physics (2023)

Future Exploration of the Outer Heliosphere and Very Local Interstellar Medium by Interstellar Probe

- P. C. Brandt

- E. Provornikova

- E. J. Zirnstein

Space Science Reviews (2023)

Direct observation of relativistic broken plasma waves

- Omri Seemann

- Victor Malka

Nature Physics (2022)

Observations of the Outer Heliosphere, Heliosheath, and Interstellar Medium

- J. D. Richardson

- L. F. Burlaga

- R. von Steiger

Space Science Reviews (2022)

Turbulence in the Outer Heliosphere

- Federico Fraternale

- Laxman Adhikari

- Lingling Zhao

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Object Information

- Planetarium

Voyager 1 live position and data

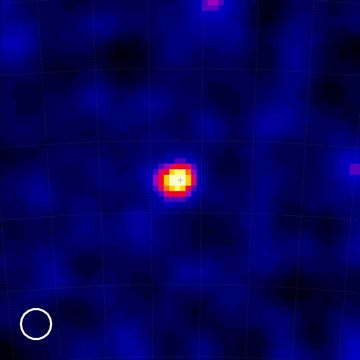

This page shows Voyager 1 location and other relevant astronomical data in real time. The celestial coordinates, magnitude, distances and speed are updated in real time and are computed using high quality data sets provided by the JPL Horizons ephemeris service (see acknowledgements for details). The sky map shown in the background represents a rectangular portion of the sky 60x40 arcminutes wide. By comparison the diameter of the full Moon is about 30 arcmins, so the full horizontal extent of the map is approximately 2 full Moons wide. Depending on the device you are using, the map can be dragged horizondally or vertically using the mouse or touchscreen. The deep sky image in the background is provided by the Digitized Sky Survey ( acknowledgements ).

Current close conjunctions

List of bright objects (stars brighter than magnitude 9.0 and galaxies brighter than magmitude 14.0) close to Voyager 1 (less than 1.5 degrees):

Additional resources

- 15 Days Ephemerides

- Interactive Sky Map (Planetarium)

- Rise & Set Times

- Distance from Earth

Astronomy databases

- The Digitized Sky Survey, a photographic survey of the whole sky created using images from different telescopes, including the Oschin Schmidt Telescope on Palomar Mountain

- The Hipparcos Star Catalogue, containing more than 100.000 bright stars

- The PGC 2003 Catalogue, containing information about 1 million galaxies

- The GSC 2.3 Catalogue, containing information about more than 2 billion stars and galaxies

News | April 28, 2023

Nasa's voyager will do more science with new power strategy.

The plan will keep Voyager 2’s science instruments turned on a few years longer than previously anticipated, enabling yet more revelations from interstellar space.

Launched in 1977, the Voyager 2 spacecraft is more than 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) from Earth, using five science instruments to study interstellar space. To help keep those instruments operating despite a diminishing power supply, the aging spacecraft has begun using a small reservoir of backup power set aside as part of an onboard safety mechanism. The move will enable the mission to postpone shutting down a science instrument until 2026, rather than this year.

Voyager 2 and its twin Voyager 1 are the only spacecraft ever to operate outside the heliosphere, the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields generated by the Sun. The probes are helping scientists answer questions about the shape of the heliosphere and its role in protecting Earth from the energetic particles and other radiation found in the interstellar environment.

“The science data that the Voyagers are returning gets more valuable the farther away from the Sun they go, so we are definitely interested in keeping as many science instruments operating as long as possible,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes power themselves with radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. The continual decay process means the generator produces slightly less power each year. So far, the declining power supply hasn’t impacted the mission’s science output, but to compensate for the loss, engineers have turned off heaters and other systems that are not essential to keeping the spacecraft flying.

With those options now exhausted on Voyager 2, one of the spacecraft’s five science instruments was next on their list. (Voyager 1 is operating one less science instrument than its twin because an instrument failed early in the mission. As a result, the decision about whether to turn off an instrument on Voyager 1 won’t come until sometime next year.)

In search of a way to avoid shutting down a Voyager 2 science instrument, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the instruments in case the spacecraft’s voltage – the flow of electricity – changes significantly. Because a fluctuation in voltage could damage the instruments, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that triggers a backup circuit in such an event. The circuit can access a small amount of power from the RTG that’s set aside for this purpose. Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating.

Although the spacecraft’s voltage will not be tightly regulated as a result, even after more than 45 years in flight, the electrical systems on both probes remain relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team is also able to monitor the voltage and respond if it fluctuates too much. If the new approach works well for Voyager 2, the team may implement it on Voyager 1 as well.

“Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we’ve determined that it’s a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at JPL. “We’ve been monitoring the spacecraft for a few weeks, and it seems like this new approach is working.”

The Voyager mission was originally scheduled to last only four years, sending both probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the boundary in 2012, while Voyager 2 (traveling slower and in a different direction than its twin) reached it in 2018.

More About the Mission

A division of Caltech in Pasadena, JPL built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/voyager

Calla Cofield Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 626-808-2469 [email protected] 2023-059

You Might Also Like

NASA's Ingenious Efforts to Restore Voyager 1's Interstellar Communications on May,2022

V oyager 1, the venerable space probe and humanity’s most distant emissary, has encountered a communication hurdle that has persisted for months, leading to a valiant effort by NASA engineers to comprehend and rectify the anomaly.

For over 45 years, Voyager 1 has been gliding through the cosmos, and in its lifetime, it has delivered invaluable data on planets like Jupiter and Saturn, as well as a solitary image of Earth from the outskirts of our solar system. Yet, as it cruises over 15 billion miles from Earth, it faces a unique challenge: a breakdown in the way it communicates its observations and status back to ground control.

In May 2022, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) engineers noticed the glitch when Voyager 1 began transmitting nonsensical data. This data, meant to inform mission controllers about the spacecraft’s operations and scientific findings, is crucial for the continuous assessment of the mission’s health and objectives. A JPL spokesperson highlighted the efforts made to resolve the issue: “The team continues information gathering and are preparing some steps that they’re hopeful will get them on a path to either understand the root of the problem and/or solve it.”

The glitch appears to be a discord between the spacecraft’s flight data system (FDS) and its telemetry modulation unit (TMU). Normally, the FDS would collect and package data for transmission to Earth, but the TMU has been sending a repeating pattern of ones and zeroes, rendering the data unintelligible.

Despite this setback, the mission team has made a breakthrough. In March 2023, after sending a ‘poke’ to the spacecraft, a signal was received that stood out from the garbled data stream. A Deep Space Network engineer decoded this and found it contained a readout of the entire FDS’s memory, a potential treasure trove for diagnosing the problem.

The issue is compounded by the enormous distance signals must travel, taking approximately 22 hours each way, leading to a slow, iterative process of trial and error as engineers send commands and await the spacecraft’s response. It’s a process the JPL spokesperson described, noting, “After they do that, they spend a few days digesting the information they got, consulting old documents to see if they can make sense of the little bits of information they can glean from things (since the telemetry data itself is unusable), and then send another command.”

Despite the challenges, the mission team remains hopeful. The wealth of data collected before the communication breakdown continues to shed light on the conditions of interstellar space, and the Voyager probes’ ongoing journey into the cosmos is a testament to human ingenuity and curiosity.

As NASA’s engineers labor to parse the received memory readout and develop potential solutions, Voyager 1’s mission remains a symbol of human achievement. Although the issue remains unresolved, the data sent back before the problem began provides an extensive understanding of interstellar space, and the work to re-establish complete communication is evidence of NASA’s relentless pursuit of knowledge.

Relevant articles:

– NASA Is Still Fighting to Save Its Historic Voyager 1 … , Gizmodo, Mar 7, 2024

– Voyager 1 sends back surprising response after ‘poke’ from NASA , CNN

– NASA finds clue while solving Voyager 1’s communication breakdown case , Space.com

– How was contact restored between NASA and Voyager 2? Here’s all you need to know about the ‘shout’ across interstellar space which retrieved the spacecraft , economictimes.com

![Voyager 1, the venerable space probe and humanity’s most distant emissary, has encountered a communication hurdle that has persisted for months, leading to a valiant effort by NASA engineers to comprehend and rectify the anomaly. For over 45 years, Voyager 1 has been gliding through the cosmos, and in its lifetime, it has delivered invaluable […] Voyager 1, the venerable space probe and humanity’s most distant emissary, has encountered a communication hurdle that has persisted for months, leading to a valiant effort by NASA engineers to comprehend and rectify the anomaly. For over 45 years, Voyager 1 has been gliding through the cosmos, and in its lifetime, it has delivered invaluable […]](https://img-s-msn-com.akamaized.net/tenant/amp/entityid/BB1l0TOd.img?w=768&h=512&m=6)

Voyagers Continues to Returns Data from The Edges of the Milky Way

More than two years after Voyager 2 looked Neptune's Great Dark Spot in the eye and darted past the frozen surface of its moon Triton, both Voyager spacecraft are continuing to return data about interplanetary space and some of our stellar neighbors near the edges of the Milky Way.

After the Voyager spacecraft flew by the four giant outer planets -- Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune -- their mission might have been over. But, in fact, these 14-year-old twins are just beginning a new phase of their journey, called the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM).

As the Voyagers cruise gracefully in the solar wind, their fields, particles and waves instruments are studying the space around them while searching for the elusive heliopause -- the outer edge of our solar system.

The heliopause is the outermost boundary of the solar wind, where the interstellar medium restricts the outward flow of the solar wind and confines it within a magnetic bubble called the heliosphere. The solar wind is made up of electrically charged atomic particles, composed primarily of ionized hydrogen, that stream outward from the Sun. "The termination shock is the first signal that we are approaching the heliopause. It's the area where the solar wind starts slowing down," said Voyager Project Scientist and JPL's Director, Dr. Edward C. Stone. Mission scientists now anticipate that the spacecraft may cross the termination shock by the end of the century. Exactly where the heliopause is remains a mystery. Its long been thought to be located some 75 to 150 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. (One AU is equal to 150 million kilometers (93 million miles), or the distance from the Earth to the Sun.) Any speculation about where the heliopause is or what it is like, has come only from computer models and theories. "Voyager 1 is likely to return the first direct evidence from the heliopause and what lies beyond it," Stone said.

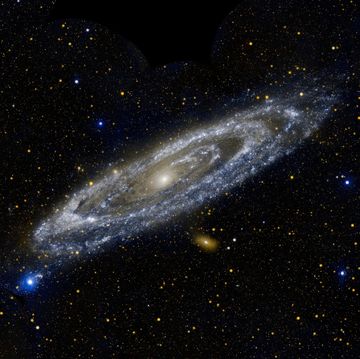

Yet the Voyagers are not sitting idly by as they wait to cross over into interstellar space. Both spacecraft are involved in an extensive program of ultraviolet astronomy that allows them to study active galaxies, quasars and white dwarf stars, in ways unlike any other spacecraft or telescope in existence.

Voyager's ultraviolet spectrometers are the only way scientists can currently observe celestial objects in a unique region in the short end of the ultraviolet portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. "Voyager's instruments allow it to observe things at wavelengths that are for the most part unavailable to other spacecraft," said Dr. Jay Holberg, a member of Voyager's ultraviolet subsystem team.

The Voyagers have become space-based ultraviolet observatories and their unique location in the universe gives astronomers the best vantage point they have ever had for looking at celestial objects that emit ultraviolet radiation. "The light that Voyager is sensitive to has to be observed in outer space," said Holberg.

Voyager's ultraviolet instruments are best suited to study the two extreme phases of a star's life -- its birth and its death. Thus the Voyagers are currently gathering data on early blue stars as well as other white dwarf stars nearing the end of their lifetime. "Voyager is helping us get a better handle on exactly how much energy these hot stars emit," Holberg said.

Now that Voyager's primary mission of exploring the outer planets is over, there are fewer constraints on the science team when it comes to programming the spacecrafts' observations. "We can sit on these things for very long periods of time and watch these stars go through their phases," Holberg said.

Stars can be very active, but also unpredictable. "We don't know when a star will do something. If we want to sit there and wait, we can do it in the hopes that the star will go through an outburst and Voyager will be there to observe it," he continued. Voyager can now stare at an object for days and even weeks at a time to thoroughly map it and the region around it.

Since the beginning of the interstellar mission, the Voyager project has been conducting a guest observer program which allows astronomers from around the world to make proposals and apply for time to use the Voyager ultraviolet spectrometer in much the same way that astronomers apply for time at ground-based observatories. This program enables scientists to make simultaneous observations of the same object using Voyager and ground-based telescopes.

The cameras on the spacecraft have been turned off and the ultraviolet instrument is the only experiment on the scan platform that is still functioning. Voyager scientists expect to continue to receive data from the ultraviolet spectrometers at least until the year 2000. At that time, there will not be enough electrical power for the heaters to keep the ultraviolet instrument warm enough to operate.

Yet there are several other fields and particle instruments that can continue to send back data as long as the spacecraft stay alive. They include: the cosmic ray subsystem, the low-energy charged particle instrument, the magnetometer, the plasma subsystem, the plasma wave subsystem and the planetary radio astronomy instrument. Barring any catastrophic events, JPL should be able to retrieve this information for at least the next 20 and perhaps even the next 30 years.

"In exploring the four outer planets, Voyager has already had an epic journey of discovery. Even so, their journey is less than half over with more discoveries awaiting the first contact with interstellar space," Stone said. "The Voyagers revealed how limited our imaginations really were about our solar system, and I expect that as they continue toward interstellar space, they will again surprise us with unimagined discoveries of this never-before-visited place which awaits us beyond our planetary neighborhood."

Voyager 1 is now 7 billion kilometers (4.3 billion miles) from Earth, traveling at a heliocentric velocity of 63,800 km/hr (39,700 mph). Voyager 2, traveling in the opposite direction from its twin, is 5.3 billion kilometers (3.3 billion miles) from Earth with a heliocentric velocity of 59,200 km/hr (36,800 mph).

The Voyager Interstellar Mission is managed by JPL and sponsored by NASA's Office of Space Science and Applications, Washington, DC.

- Central Oregon

- Oregon-Northwest

- Crime Stoppers

- KTVZ.COM Polls

- Special Reports

- NewsChannel 21 Investigates

- Ask the Mayor

- Interactive Radar

- Local Forecast

- Snow Report

- Road Conditions – Weather Webcams

- Prep Scoreboard

- Livestream Newscasts

- Livestream Special Coverage

- Local Videos

- Photo Galleries

- 21 Cares For Kids

- Community Billboard

- Community Links

- One Class At a Time

- Pay it Forward

- House & Home

- Entertainment

- Events Calendar

- Pump Patrol

- Pet Pics Sweepstakes

- Sunrise Birthdays

- Submit Tips, Pics and Video

- KTVZ Careers

- Central Oregon Careers

- Email Newsletters

- Advertise with NPG of Oregon

- Careers and Internships

- Closed Captioning

- Download Our Apps

- EEO Public Filing

- FCC Public File

- NewsChannel 21 Team

- On-Air Status

- Receiving KTVZ

- TV Listings

Aging Voyager 1 sends back surprising response after ‘poke’ from Earth

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

(CNN) — Engineers have sent a “poke” to the Voyager 1 probe and received a potentially encouraging response as they hope to fix a communication issue with the aging spacecraft that has persisted for five months.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, are venturing through uncharted cosmic territory along the outer reaches of the solar system.

While Voyager 1 has continued to relay a steady radio signal to its mission control team on Earth, that signal has not carried any usable data since November, which has pointed to an issue with one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers.

A new signal recently received from the spacecraft suggests that the NASA mission team may be making progress in its quest to understand what Voyager 1 is experiencing. Voyager 1 is currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth at about 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away.

Meanwhile, Voyager 2 has traveled more than 12.6 billion miles (20.3 billion kilometers) from our planet. Both are in interstellar space and are the only spacecraft ever to operate beyond the heliosphere, the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond the orbit of Pluto.

Initially designed to last five years, the Voyager probes are the two longest-operating spacecraft in history. Their exceptionally long life spans mean that both spacecraft have provided additional insights about our solar system and beyond after achieving their preliminary goals of flying by Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune decades ago.

But both probes have faced challenges along the way as they age.

Cosmic communication breakdown

The mission team first noticed the communication issue with Voyager 1 on November 14, 2023, when the flight data system’s telemetry modulation unit began sending a repeating pattern of code.

Voyager 1’s flight data system collects information from the spacecraft’s science instruments and bundles it with engineering data that reflects the current health status of Voyager 1. Mission control on Earth receives that data in binary code, or a series of ones and zeroes.

But since November, Voyager 1’s flight data system has been stuck in a loop.

The spacecraft can still receive and carry out commands transmitted from the mission team, but a problem with that telecommunications unit meant no science or engineering data from Voyager 1 was transmitting to Earth.

Since discovering the issue, the mission team has attempted sending commands to restart the computer system and learn more about the underlying cause of the issue.

The team sent a command, called a “poke,” to Voyager 1 on March 1 to get the flight data system to run different software sequences in case some type of glitch was causing the issue.

On March 3, the team noticed that activity from one part of the flight data system stood out from the rest of the garbled data. While the signal wasn’t in the format the Voyager team is used to when the flight data system is functioning as expected, an engineer with NASA’s Deep Space Network was able to decode it.

The Deep Space Network is a system of radio antennas on Earth that help the agency communicate with the Voyager probes and other spacecraft exploring our solar system.

The decoded signal included a readout of the entire flight data system’s memory, according to an update NASA shared .

“The (flight data system) memory includes its code, or instructions for what to do, as well as variables, or values used in the code that can change based on commands or the spacecraft’s status,” according to a NASA blog post. “It also contains science or engineering data for downlink. The team will compare this readout to the one that came down before the issue arose and look for discrepancies in the code and the variables to potentially find the source of the ongoing issue.”

How the Voyager probes keep going

Voyager 1 is so far away that it takes 22.5 hours for commands sent from Earth to reach the spacecraft. Additionally, the team must wait 45 hours to receive a response. Currently, the team is analyzing Voyager 1’s memory readout after initially beginning the decoding process on March 7 and finding the readout three days later.

“Using that information to devise a potential solution and attempt to put it into action will take time,” according to the space agency.

The last time Voyager 1 experienced a similar, but not identical, issue with the flight data system was in 1981, and the current problem does not appear to be connected to other glitches the spacecraft has experienced in recent years.

Over time, both spacecraft have encountered unexpected issues and dropouts, including a seven-month period in 2020 when Voyager 2 couldn’t communicate with Earth. In August 2023, the mission team used a long-shot “shout” technique to restore communications with Voyager 2 after a command inadvertently oriented the spacecraft’s antenna in the wrong direction.

As the aging twin Voyager probes continue exploring the cosmos, the team has slowly turned off instruments on these “senior citizens” to conserve power and extend their missions , Voyager’s project manager Suzanne Dodd previously told CNN.

The-CNN-Wire ™ & © 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Jump to comments ↓

CNN Newsource

Related articles.

Denmark closes major shipping strait over faulty missile launcher

European police seize lamborghinis and rolexes over alleged $650m covid-19 fraud, us tourist on safari in zambia killed by charging elephant.

Wear red and green to experience the Purkinje effect during the total solar eclipse

KTVZ NewsChannel 21 is committed to providing a forum for civil and constructive conversation.

Please keep your comments respectful and relevant. You can review our Community Guidelines by clicking here

If you would like to share a story idea, please submit it here .

Voyager 1 Has Gone Mysteriously—and Perhaps Fatally—Silent in Deep Space

Engineers are scrambling to save the storied spacecraft after it experienced an unforeseen glitch.

- Voyager 1 is one of the most inspiring spacecraft that NASA has ever created, as its the first spacecraft to cross our star’s heliopause.

- For nearly 50 years, the spacecraft has been bound for parts unknown, but NASA engineers currently can’t communicate with it due to a corrupted piece of data.

- One NASA official says it would be a “miracle” if the team could recover the spacecraft, but they haven’t given up trying.

“Had the Voyager mission ended after the Jupiter and Saturn flybys alone, it still would have provided the material to rewrite astronomy textbooks,” NASA wrote . “But having doubled their already ambitious itineraries, the Voyagers returned to Earth information over the years that has revolutionized the science of planetary astronomy.”

However, that revolution may be coming to an end for Voyager 1 —one of NASA’s most awe-inspiring spacecraft and the farthest human-made object from Earth, at a distance of some 15 billion miles. That’s because NASA is still struggling with a computer glitch, which first popped up in November of 2023 , that’s preventing NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) team from contacting their far-flung robotic explorer.

NASA believes the problem has something to do with the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS), which is sending back nonsense 1s and 0s in a repeated pattern. According to Ars Technica , it’s likely that a “bit of corrupted memory” is the culprit, but because it’s impacting telemetry data , the team has no way of identifying the problem. Although their receiving a signal that the spacecraft is alive and well, the NASA team and Voyager 1 are effectively incommunicado.

Other complications are starting to arise as a result of just how old these spacecraft are. As NASA officials note, these spacecraft have been trucking through space for so long that most of the original Voyager team—the people who built these things—are no longer among the living. While detailed documentation helps, the loss of human experience is certainly being felt right now, especially with the Voyager 1 spacecraft. It’s also not easy to solve a computer problem when every command takes roughly 45 hours to get a response.

“It would be the biggest miracle if we get it back. We certainly haven’t given up,” Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager, told Ars Technica in an interview. “There are other things we can try. But this is, by far, the most serious since I’ve been project manager.”

Although things look dire, the Voyager team hasn’t given up hope. In the next few weeks, engineers will try to locate the corrupted memory by switching the spacecraft into different operating modes—some of which haven’t been used in 40 years (back when Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 conducted their primary mission of studying Jupiter and Saturn ).

If the NASA fails to recover Voyager 1, it’ll still be a mission for the history books. And Voyager 2—while not yet as far away as Voyager 1—still has operational plans until at least 2026 . Don’t forget New Horizons either, whose flyby of Pluto in 2015 fascinated the world . It's currently racing toward the edge of our Solar System as we speak, but it won’t reach its interstellar destination until 2043.

For now, we can only hope that NASA engineers can straighten out those 1s and 0s, while also remaining grateful to live in a time and place where humans are taking their first steps out beyond their own Solar System .

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} Deep Space .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

A Giant Star Looks Like It's Defying Astrophysics

Meteorite Strike Was Actually Just a Truck

Theory Says Our Universe Is Eating Baby Universes

Astronomers Caught Dark Matter in the Cosmic Web

A Study Says Black Holes Can Create Space Lasers

Experts Solved the Case of the Missing Sulfur

Experts Are About to Map the Fabric of Space-Time

This Is the Most Hi-Res Image of a Gamma Ray Ever

Asteroid Matter May Contain 'Seeds of Life'

Neutron Star May Reveal Life’s Essence

This May Be the Tiniest Black Hole We’ve Ever Seen

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft is talking nonsense. Its friends on Earth are worried

Nell Greenfieldboyce

This artist's impression shows one of the Voyager spacecraft moving through the darkness of space. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

This artist's impression shows one of the Voyager spacecraft moving through the darkness of space.

The last time Stamatios "Tom" Krimigis saw the Voyager 1 space probe in person, it was the summer of 1977, just before it launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Now Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles away, beyond what many consider to be the edge of the solar system. Yet the on-board instrument Krimigis is in charge of is still going strong.

"I am the most surprised person in the world," says Krimigis — after all, the spacecraft's original mission to Jupiter and Saturn was only supposed to last about four years.

These days, though, he's also feeling another emotion when he thinks of Voyager 1.

"Frankly, I'm very worried," he says.

Ever since mid-November, the Voyager 1 spacecraft has been sending messages back to Earth that don't make any sense. It's as if the aging spacecraft has suffered some kind of stroke that's interfering with its ability to speak.

"It basically stopped talking to us in a coherent manner," says Suzanne Dodd of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who has been the project manager for the Voyager interstellar mission since 2010. "It's a serious problem."

Instead of sending messages home in binary code, Voyager 1 is now just sending back alternating 1s and 0s. Dodd's team has tried the usual tricks to reset things — with no luck.

It looks like there's a problem with the onboard computer that takes data and packages it up to send back home. All of this computer technology is primitive compared to, say, the key fob that unlocks your car, says Dodd.

"The button you press to open the door of your car, that has more compute power than the Voyager spacecrafts do," she says. "It's remarkable that they keep flying, and that they've flown for 46-plus years."

Each of the Voyager probes carries an American flag and a copy of a golden record that can play greetings in many languages. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

Each of the Voyager probes carries an American flag and a copy of a golden record that can play greetings in many languages.

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, have outlasted many of those who designed and built them. So to try to fix Voyager 1's current woes, the dozen or so people on Dodd's team have had to pore over yellowed documents and old mimeographs.

"They're doing a lot of work to try and get into the heads of the original developers and figure out why they designed something the way they did and what we could possibly try that might give us some answers to what's going wrong with the spacecraft," says Dodd.

She says that they do have a list of possible fixes. As time goes on, they'll likely start sending commands to Voyager 1 that are more bold and risky.

"The things that we will do going forward are probably more challenging in the sense that you can't tell exactly if it's going to execute correctly — or if you're going to maybe do something you didn't want to do, inadvertently," says Dodd.

Linda Spilker , who serves as the Voyager mission's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says that when she comes to work she sees "all of these circuit diagrams up on the wall with sticky notes attached. And these people are just having a great time trying to troubleshoot, you know, the 60's and 70's technology."

"I'm cautiously optimistic," she says. "There's a lot of creativity there."

Still, this is a painstaking process that could take weeks, or even months. Voyager 1 is so distant, it takes almost a whole day for a signal to travel out there, and then a whole day for its response to return.

"We'll keep trying," says Dodd, "and it won't be quick."

In the meantime, Voyager's 1 discombobulation is a bummer for researchers like Stella Ocker , an astronomer with Caltech and the Carnegie Observatories

"We haven't been getting science data since this anomaly started," says Ocker, "and what that means is that we don't know what the environment that the spacecraft is traveling through looks like."

After 35 Years, Voyager Nears Edge Of Solar System

That interstellar environment isn't just empty darkness, she says. It contains stuff like gas, dust, and cosmic rays. Only the twin Voyager probes are far out enough to sample this cosmic stew.

"The science that I'm really interested in doing is actually only possible with Voyager 1," says Ocker, because Voyager 2 — despite being generally healthy for its advanced age — can't take the particular measurements she needs for her research.

Even if NASA's experts and consultants somehow come up with a miraculous plan that can get Voyager 1 back to normal, its time is running out.

The two Voyager probes are powered by plutonium, but that power system will eventually run out of juice. Mission managers have turned off heaters and taken other measures to conserve power and extend the Voyager probes' lifespan.

"My motto for a long time was 50 years or bust," says Krimigis with a laugh, "but we're sort of approaching that."

In a couple of years, the ebbing power supply will force managers to start turning off science instruments, one by one. The very last instrument might keep going until around 2030 or so.

When the power runs out and the probes are lifeless, Krimigis says both of these legendary space probes will basically become "space junk."

"It pains me to say that," he says. While Krimigis has participated in space missions to every planet, he says the Voyager program has a special place in his heart.

Spilker points out that each spacecraft will keep moving outward, carrying its copy of a golden record that has recorded greetings in many languages, along with the sounds of Earth.

"The science mission will end. But a part of Voyager and a part of us will continue on in the space between the stars," says Spilker, noting that the golden records "may even outlast humanity as we know it."

Krimigis, though, doubts that any alien will ever stumble across a Voyager probe and have a listen.

"Space is empty," he says, "and the probability of Voyager ever running into a planet is probably slim to none."

It will take about 40,000 years for Voyager 1 to approach another star; it will come within 1.7 light years of what NASA calls "an obscure star in the constellation Ursa Minor" — also known as the Little Dipper.

If NASA greenlights this interstellar mission, it could last 100 years

Knowing that the Voyager probes are running out of time, scientists have been drawing up plans for a new mission that, if funded and launched by NASA, would send another probe even farther out into the space between stars.

"If it happens, it would launch in the 2030s," says Ocker, "and it would reach twice as far as Voyager 1 in just 50 years."

- space science

- space exploration

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

The Voyager Planetary Mission

The twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were launched by NASA in separate months in the summer of 1977 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. As originally designed, the Voyagers were to conduct closeup studies of Jupiter and Saturn, Saturn's rings, and the larger moons of the two planets.

To accomplish their two-planet mission, the spacecraft were built to last five years. But as the mission went on, and with the successful achievement of all its objectives, the additional flybys of the two outermost giant planets, Uranus and Neptune, proved possible -- and irresistible to mission scientists and engineers at the Voyagers' home at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

As the spacecraft flew across the solar system, remote-control reprogramming was used to endow the Voyagers with greater capabilities than they possessed when they left the Earth. Their two-planet mission became four. Their five-year lifetimes stretched to 12 and more.

Eventually, between them, Voyager 1 and 2 would explore all the giant outer planets of our solar system, 48 of their moons, and the unique systems of rings and magnetic fields those planets possess.

Had the Voyager mission ended after the Jupiter and Saturn flybys alone, it still would have provided the material to rewrite astronomy textbooks. But having doubled their already ambitious itineraries, the Voyagers returned to Earth information over the years that has revolutionized the science of planetary astronomy, helping to resolve key questions while raising intriguing new ones about the origin and evolution of the planets in our solar system.

History of the Voyager Mission

The Voyager mission was designed to take advantage of a rare geometric arrangement of the outer planets in the late 1970s and the 1980s which allowed for a four-planet tour for a minimum of propellant and trip time. This layout of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, which occurs about every 175 years, allows a spacecraft on a particular flight path to swing from one planet to the next without the need for large onboard propulsion systems. The flyby of each planet bends the spacecraft's flight path and increases its velocity enough to deliver it to the next destination. Using this "gravity assist" technique, first demonstrated with NASA's Mariner 10 Venus/Mercury mission in 1973-74, the flight time to Neptune was reduced from 30 years to 12.

While the four-planet mission was known to be possible, it was deemed to be too expensive to build a spacecraft that could go the distance, carry the instruments needed and last long enough to accomplish such a long mission. Thus, the Voyagers were funded to conduct intensive flyby studies of Jupiter and Saturn only. More than 10,000 trajectories were studied before choosing the two that would allow close flybys of Jupiter and its large moon Io, and Saturn and its large moon Titan; the chosen flight path for Voyager 2 also preserved the option to continue on to Uranus and Neptune.

From the NASA Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, Voyager 2 was launched first, on August 20, 1977; Voyager 1 was launched on a faster, shorter trajectory on September 5, 1977. Both spacecraft were delivered to space aboard Titan-Centaur expendable rockets.

The prime Voyager mission to Jupiter and Saturn brought Voyager 1 to Jupiter on March 5, 1979, and Saturn on November 12, 1980, followed by Voyager 2 to Jupiter on July 9, 1979, and Saturn on August 25, 1981.

Voyager 1's trajectory, designed to send the spacecraft closely past the large moon Titan and behind Saturn's rings, bent the spacecraft's path inexorably northward out of the ecliptic plane -- the plane in which most of the planets orbit the Sun. Voyager 2 was aimed to fly by Saturn at a point that would automatically send the spacecraft in the direction of Uranus.

After Voyager 2's successful Saturn encounter, it was shown that Voyager 2 would likely be able to fly on to Uranus with all instruments operating. NASA provided additional funding to continue operating the two spacecraft and authorized JPL to conduct a Uranus flyby. Subsequently, NASA also authorized the Neptune leg of the mission, which was renamed the Voyager Neptune Interstellar Mission.

Voyager 2 encountered Uranus on January 24, 1986, returning detailed photos and other data on the planet, its moons, magnetic field and dark rings. Voyager 1, meanwhile, continues to press outward, conducting studies of interplanetary space. Eventually, its instruments may be the first of any spacecraft to sense the heliopause -- the boundary between the end of the Sun's magnetic influence and the beginning of interstellar space. (Voyager 1 entered Interstellar Space on August 25, 2012.)

Following Voyager 2's closest approach to Neptune on August 25, 1989, the spacecraft flew southward, below the ecliptic plane and onto a course that will take it, too, to interstellar space. Reflecting the Voyagers' new transplanetary destinations, the project is now known as the Voyager Interstellar Mission.

Voyager 1 is now leaving the solar system, rising above the ecliptic plane at an angle of about 35 degrees at a rate of about 520 million kilometers (about 320 million miles) a year. Voyager 2 is also headed out of the solar system, diving below the ecliptic plane at an angle of about 48 degrees and a rate of about 470 million kilometers (about 290 million miles) a year.

Both spacecraft will continue to study ultraviolet sources among the stars, and the fields and particles instruments aboard the Voyagers will continue to search for the boundary between the Sun's influence and interstellar space. The Voyagers are expected to return valuable data for two or three more decades. Communications will be maintained until the Voyagers' nuclear power sources can no longer supply enough electrical energy to power critical subsystems.

The cost of the Voyager 1 and 2 missions -- including launch, mission operations from launch through the Neptune encounter and the spacecraft's nuclear batteries (provided by the Department of Energy) -- is $865 million. NASA budgeted an additional $30 million to fund the Voyager Interstellar Mission for two years following the Neptune encounter.