Advertisement

Supported by

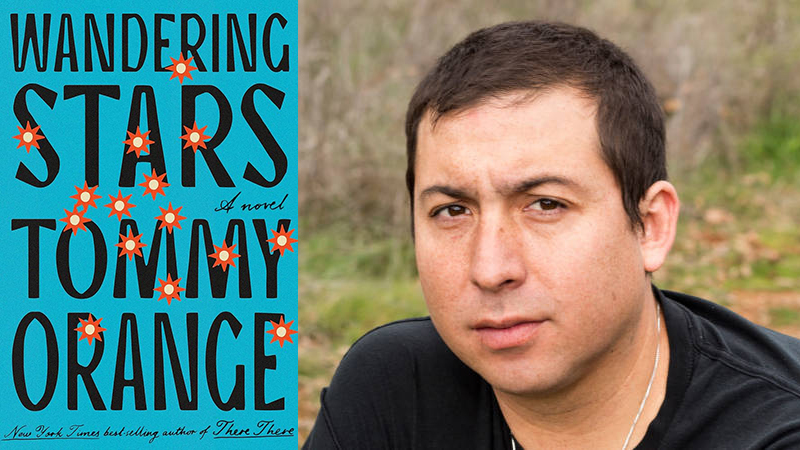

Tommy Orange’s ‘There There’ Sequel Is a Towering Achievement

“Wandering Stars” considers the fallout of colonization and the forced assimilation of Native Americans.

- Share full article

By Jonathan Escoffery

Jonathan Escoffery is the author of the linked story collection “If I Survive You,” which was nominated for the 2022 National Book Award and a finalist for the 2023 Booker Prize.

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

- Bookshop.org

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

WANDERING STARS , by Tommy Orange

Tommy Orange triumphantly returns with “Wandering Stars,” the follow-up to his groundbreaking 2018 debut, “ There There . ” Part prequel, part sequel, yet wholly standing on its own, Orange’s novel follows the descendants of Jude Star, a Cheyenne survivor of the 1864 Sand Creek massacre , for more than a century and a half, before catching up with the present day and landing in the aftermath of the first book’s harrowing climax.

The novel begins with an address on the American government’s multipronged campaign to eliminate the original “inhabitants of these American lands.” One such campaign came with the slogan “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” Orange tells us, referring to the boarding schools where Indigenous children were forced to suffer all manners of torture in the name of assimilation.

But, Orange continues, “all the Indian children who were ever Indian children never stopped being Indian children … whose Indian children went on to have Indian children.” In spite of the calculated terror, and the incalculable loss, the government’s campaign failed and could only ever fail. This framing is part of what’s so special about this book: As we move through generations of the family — as Stars become Bear Shields, who become Red Feathers — and even as knowledge of their histories and customs becomes muddled or lost to time and tragedy, Jude Star’s lineage, and that of his people, remains unbroken.

Still, when the novel enters the 21st century, members of the Red Feather family lament society’s apparent refusal to see Native Americans as existing in the present day. While watching an Avengers movie, Lony, the youngest of the Red Feather brothers, imagines what powers a Native American superhero would have. He makes a list that includes “Can Fly (because feathers)” and “Invisibility (because no one knows we’re still here).”

Orange expands his focus on identity to consider the fraught relationship between race and blood. We hear from a high school student named Sean Price, an adoptee raised by white parents, who has just received the results of his DNA test. “He’d already assumed he was part Black,” Orange writes. “There was no mistaking the look you got if you were assumed Black or part Black in a white community — whether you were or were not all or part.”

Blackness, according to Sean, lies in others’ assumptions and becomes most pressingly about how one is perceived and treated. The point is emphasized when Sean and another adoptee friend make a habit of riding the city bus from the Oakland hills down into predominantly Black neighborhoods, where they are unbothered, and where they can “disappear completely” from the white gaze. But given his upbringing, “Sean didn’t feel he had the right to belong to any of what it might mean to be Black from Oakland.”

Sean considers what to make of the DNA results, which reveal European, Native American and African ancestry, and determines that “he couldn’t pretend to now be Native American, not white either, but he would continue to be considered Black, holding the knowledge of his Native American heritage out in front of him like an empty bowl.” Data about his ancestry alone isn’t enough to allow him to feel he can claim it.

Later, Sean seeks guidance from his schoolmate Orvil Red Feather, asking, “So, like, can I say Indian?,” to which Orvil responds, “If you’re Indian.” The novel does not include the percentages that typically accompany these DNA test results, perhaps to dissuade readers from attempting to construct Sean’s identity on his behalf. It’s as if Orange is saying, You can’t decide this for Sean.

It’d be a mistake to think that the power of “Wandering Stars” lies solely in its astute observations, cultural commentary or historical reclamations, though these aspects of the novel would make reading it very much worthwhile. But make no mistake, this book has action! Suspense! The characters are fully formed and they get going right out of the gate. Our first moments with Jude Star are heart-pounding, and our final moments with him, as we find him on the cusp of a decision that will forever change his family’s fate, will make you want to scream “Don’t do it!” The fact that you’ll want to scream “Do it!” just as strongly speaks to the power of Orange’s storytelling abilities.

“There There” fans will be happy to see the return of the half sisters Jacquie and Opal, and to have questions from Orange’s first novel answered. Will the once-estranged Jacquie stick around to help raise her grandsons? Will she relapse again? What led her to run away and leave Opal behind in her teenage years?

As the fallout of colonization and forced assimilation takes its toll on the family, its most definitive impact is addiction. Jude battles alcoholism and, like a family curse, addiction wends its way through his descendants, reaching even the youngest generation of Red Feathers. Sean and Orvil become fast friends, having in common dead mothers, recent hospitalizations and a growing desire to sustain the high they experience via the painkillers they were prescribed for their respective injuries. Add to the boys’ blossoming addictions the fact that Sean’s adoptive father has become a drug dealer and manufacturer with a seemingly endless supply of pain pills on hand, and the friendship becomes a powder keg. It would be easy to reduce this friendship to its toxic elements, but the boys also share a love for musical instruments and a brotherly love for each other that’s difficult to root against.

Orange’s ability to highlight the contradictory forces that coexist within friendships, familial relationships and the characters themselves, who contend with holding private and public identities, makes “Wandering Stars” a towering achievement.

WANDERING STARS | By Tommy Orange | Knopf | 315 pp. | $29

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

‘A Lot of Us Are Gone’: Nationwide protests over racial inequality led publishing houses to pledge that they would recruit more people of color. The departure of prominent Black editors and executives has led some to question publishers’ commitment to diversify .

The Pentagon’s U.F.O. Hunt: Luis Elizondo made headlines when he resigned after running a shadowy Pentagon program investigating U.F.O.s. In a new memoir , he asserts that a government-run program has retrieved technology and biological remains of nonhuman origin from U.F.O. crashes.

The Essential Shel Silverstein: He was irreverent, absurdist and ahead of his time. Here’s the best of the best by the groovy pied piper who made poetry fun .

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

WANDERING STARS

by Tommy Orange ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 27, 2024

A searing study of the consequences of a genocide.

A lyrical, multigenerational exploration of Native American oppression.

Orange’s second novel is partly a sequel to his acclaimed 2018 debut, There There —its second half centers on members of the Red Feather family after the events of the first book. But Orange moves the story back as well as forward. He rewinds to 1864’s Sand Creek Massacre, in which Natives were killed or displaced by the U.S. Army. One survivor (and Red Feather family ancestor), Jude Star, is a mute man imprisoned and sent to Carlisle Indian Industrial School, one of several institutions designed to strip Native Americans of their history and folklore. As Orange tracks the generations that follow, he suggests that such schools did their jobs well, but imperfectly—essential traces of Native heritage endure despite decades of murder, poverty, and addiction. That theme crystallizes as the story shifts to 2018, depicting Orvil Red Feather’s struggles after he was shot at a powwow in Oakland, California. His path is perilous, especially thanks to a school friend with easy access to addictive pain medications. But Orvil doesn’t quite lose his grip on history, whether that’s through stories of his mother participating in the 19-month Native American occupation of Alcatraz from 1969 to 1971, or cowboys-and-Indians lore he contemplates while playing Red Dead Redemption 2 . “Everyone only thinks we’re from the past, but then we’re here, but they don’t know we’re still here,” as Orvil’s brother Lony puts it. Orange is gifted at elevating his characters without romanticizing them, and though the cast is smaller than in There There , the sense of history is deeper. And the timbre of individual voices is richer, from Orvil’s streetwise patter to the officiousness of Carlisle founder Richard Henry Pratt, determined to send “the vanishing race off into final captivity before disappearing into history forever.” He failed, but this is a powerful indictment of his—and America’s—efforts.

Pub Date: Feb. 27, 2024

ISBN: 9780593318256

Page Count: 336

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: Dec. 6, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2024

LITERARY FICTION | GENERAL FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Tommy Orange

BOOK REVIEW

by Tommy Orange

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

SEEN & HEARD

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

IT STARTS WITH US

by Colleen Hoover ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 18, 2022

Through palpable tension balanced with glimmers of hope, Hoover beautifully captures the heartbreak and joy of starting over.

The sequel to It Ends With Us (2016) shows the aftermath of domestic violence through the eyes of a single mother.

Lily Bloom is still running a flower shop; her abusive ex-husband, Ryle Kincaid, is still a surgeon. But now they’re co-parenting a daughter, Emerson, who's almost a year old. Lily won’t send Emerson to her father’s house overnight until she’s old enough to talk—“So she can tell me if something happens”—but she doesn’t want to fight for full custody lest it become an expensive legal drama or, worse, a physical fight. When Lily runs into Atlas Corrigan, a childhood friend who also came from an abusive family, she hopes their friendship can blossom into love. (For new readers, their history unfolds in heartfelt diary entries that Lily addresses to Finding Nemo star Ellen DeGeneres as she considers how Atlas was a calming presence during her turbulent childhood.) Atlas, who is single and running a restaurant, feels the same way. But even though she’s divorced, Lily isn’t exactly free. Behind Ryle’s veneer of civility are his jealousy and resentment. Lily has to plan her dates carefully to avoid a confrontation. Meanwhile, Atlas’ mother returns with shocking news. In between, Lily and Atlas steal away for romantic moments that are even sweeter for their authenticity as Lily struggles with child care, breastfeeding, and running a business while trying to find time for herself.

Pub Date: Oct. 18, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-668-00122-6

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Atria

Review Posted Online: July 26, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 2022

ROMANCE | CONTEMPORARY ROMANCE | GENERAL ROMANCE | GENERAL FICTION

More by Colleen Hoover

by Colleen Hoover

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

BOOK TO SCREEN

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Tommy Orange is back with a hypnotic new novel

‘Wandering Stars,’ by the author of ‘There There,’ explores the legacy of trauma that flows through a Native American family

Six years have passed since Tommy Orange published his debut novel, “ There There ,” but the echoes of that story still reverberate in the minds of those who read it. A member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, Orange introduced a large cast of Indians in modern-day California and drew them to the Oakland Coliseum for a powwow that offered a chance for cultural celebration, commercial enterprise, spiritual reflection and, most notably, grand larceny.

With varying degrees of success, these characters struggle to carve out a livable haven amid the caustic crosscurrents of American racism and historical amnesia. By listening sympathetically and refusing to elide their challenges — or their mistakes — Orange demonstrates that Indians are not feathered Hollywood tropes or wooden icons of Old West mythology. His fiction explores the complex challenges faced by people struggling to understand their identity within a dominant culture determined to bleach and sentimentalize the past.

During one of many poignant moments in Orange’s new novel, “ Wandering Stars ,” an Indian woman goes to a public library in the late 1950s and asks “what novels are written by Indian people.” The librarian tells her “she doesn’t think there are any.” Sixty years later, an Indian boy wonders “why there weren’t any Native American superheroes.” His older brother laments that he and his family “weren’t connected to the tribe or to their language or with the knowledge that other people had about being Native.”

This is the story of that family, their history and the enervating effects of being cut off from it. As one desperately discouraged young man tells a friend, “No Indians from when they first named us Indians would recognize us as Indians now.”

“Wandering Stars” is not technically a sequel, but it wraps around “ There There .” Readers unfamiliar with the earlier book will feel its gravitational influence as some invisible body of dark matter, but fans will find here a rich expansion of Orange’s universe.

The story opens with “America’s longest war,” more than 300 years of conflict in which Indians were massacred, starved and, euphemistically, “removed.” But Orange is interested in the twilight atrocities of that period. In one of his typically hypnotic sentences, the very grammar conveys the impossible labyrinth of survival: “When the Indian Wars began to go cold, the theft of land and tribal sovereignty bureaucratic, they came for Indian children, forcing them into boarding schools, where if they did not die of what they called consumption even while they regularly were starved; if they were not buried in duty, training for agricultural or industrial labor, or indentured servitude; were they not buried in children’s cemeteries, or in unmarked graves, not lost somewhere between the school and home having run away, unburied, unfound, lost to time, or lost between exile and refuge, between school, tribal homelands, reservation, and city; if they made it through routine beatings and rape, if they survived, made lives and families and homes, it was because of this and only this: Such Indian children were made to carry more than they were made to carry.”

One of those children is Jude Star. In 1864, he barely survives the Sand Creek massacre and goes mute in response to the trauma. The invaded world he wanders into is almost as deadly. “There was unspeakable pain and loss all about us wherever we went,” Jude says. To avoid starvation, he eventually turns himself over to U.S. soldiers and gets shipped off to a prison in Florida.

There, trapped in a program of cultural annihilation, Jude begins his conflicted relationship with White society under the tutelage of a jailer named Richard Henry Pratt, an actual historical figure who will go on to found the Carlisle Indian Industrial School . Determined to eradicate “their blanket ways,” Pratt practiced a toxic benevolence based on the principle of “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Sign up for the Book World newsletter from The Washington Post

Taught to read and write, Jude is seduced by Western classics, and he finds the Bible particularly fascinating, especially its strange echoes of Cheyenne stories. But what really perplexes him are the contradictory demands of his conquerors: Jude is repeatedly told to eradicate everything about himself that’s Indian, and yet he’s also required to represent “the vanishing race.”

“We performed being Indian for the white people. Some of us danced and drummed and sang,” Jude says. “We performed ourselves, made it look authentic for the sake of performing authenticity. Like being was for sale, and we’d sold ours.”

That corrosive paradox, forced down his throat by Pratt, seeps into Jude’s descendants. With the horrible inevitability of a Greek tragedy, his own son ends up attending the Carlisle School, where he endures similar humiliations that push him into drug addiction. Isolated and filled with self-hatred, Jude’s son becomes a man desperate to both escape and retain the past. “Most days,” Orange writes, “he just let the laudanum do what it would do to him, which he would have trouble remembering later, and hate himself for not being able to stop wiping out his own memory.”

As “Wandering Stars” sweeps through the decades, Orange gathers up moments of love and despair in stories that demonstrate what a piercing writer he is. But then, about halfway through the novel, we arrive in 2018, more than 150 years after the Sand Creek massacre. Here, Orange flares his wings and touches down for good in the home of Orvil Red Feather, the teenager wounded at the climax of “There There.”

Still recovering from being shot during the Oakland Coliseum powwow, Orvil just wants to “feel normal again.” But along with all the usual anxieties of being a teenager, he’s in the maw of an addiction to painkillers. His tender spirit is encased in a hard glaze of cynicism, and “Wandering Stars” captures his faux-tough voice so poignantly that you just want to wrap your arms around him and protect him somehow from further harm. Of course, that’s not easy for anyone to do, and Orange is terrific at the quirky interplay of kids and their elders. When Orvil admits, “I wanted to feel connected to being Native, and to being Cheyenne, but I didn’t quite know how,” no one around him knows either.

The shift in pacing and structure — essentially moving from a collection of connected short stories to a novella — gives Orange the space to explore the lives of other people in Orvil’s life, especially the great-aunt who mothers him and his brothers. “Their newly made family was a chorus of noise and a throng of pain in waiting,” Orange writes, “because it was loved, and had been saved, and so loved desperately, knowing that whatever happened to any one of them happened to every one of them.”

5 new works of historical fiction offer a window into other times

Substance abuse derails many of these lives, but the most devastating aspect of “Wandering Stars” is how Orvil’s nature-loving little brother Lony copes with being estranged from his culture. While the adults in his family are struggling to stay alive and keep the older kids out of trouble, Lony spirals into self-destruction. Denied a knowledge of his ancestors’ customs, he designs his own with the sharp tools at his disposal. Starved for sacred animals, he turns to the meat of his own body. Haunted by the Oakland powwow where Orvil almost died, “he just doesn’t want anything like what happened to ever happen again,” Orange writes. “He isn’t sure what it means, but he knows something else is necessary, something he needs to do, in secret, something required of him.”

Although his great-aunt senses this need in her joints, she’s not sure how to comfort him. “We come from prisoners of a long war that didn’t stop even when it stopped,” she thinks. “But surviving wasn’t enough. To endure or pass through endurance test after endurance test only ever gave you endurance test passing abilities. Simply lasting was great for a wall, for a fortress, but not for a person.”

It’s not too early to say that Orange is building a body of literature that reshapes the Native American story in the United States. Book by book, he’s correcting the dearth of Indian stories even while depicting the tragic cost of that silence. As one lost character in “Wandering Stars” says, “I want to come home.” Orange is getting that place ready.

Ron Charles reviews books and writes the Book Club newsletter for The Washington Post.

Wandering Stars

By Tommy Orange

Knopf. 315 pp. $29

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

In Tommy Orange’s Latest, a Family Tree Grows from Severed Roots

What happened in the apple orchard that so frightened the children? Something had been half-glimpsed or heard, something in the night. Rumors sparked but didn’t catch. The children kept their distance, and stayed close to the nearby school. Years passed. The school was shut down. The buildings stood. The orchard grew wild. And, one day, a tourist out walking in the area discovered a piece of bone—a child’s rib.

In 2021, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation began an investigation. Ground-penetrating radar detected what seemed to be evidence of some two hundred graves, presumably belonging to Native American children, in the land surrounding the Kamloops Indian Residential School, in British Columbia. A few weeks later, Cowessess First Nation reported signs of seven hundred and fifty-one graves around the Marieval Indian Residential School, in southern Saskatchewan. As the earth was probed, so were the wounds that were the legacy of residential schools, a cornerstone of colonial policy toward Native Americans across the continent for more than a century.

Hundreds of boarding schools operated in the United States and Canada with the aim of severing children’s spiritual and cultural ties and accelerating their assimilation. “Kill the Indian to save the man” was the guiding principle of the American Army captain Richard Pratt, who established the nation’s first such institution, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, at an old Army barracks in Pennsylvania. Children were forcibly removed from their communities, given new names, and made to convert to Christianity. (Many of the schools were run by the Catholic Church.) Native languages and spiritual practices were forbidden, and punishments could be brutal. St. Anne’s school, which operated until 1976, in Fort Albany First Nation, in Ontario, became notorious for shocking students in a homemade electric chair. Other schools used whips and cattle prods. Still others subjected the children to experiments, deliberately withholding food and medical care. In 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released an investigative report on the federal Indian boarding schools, which found “rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.” Illness and malnourishment were widespread. Thousands of children, perhaps tens of thousands, disappeared. At the Carlisle Indian School, which operated for four decades, more than two hundred children died, some barely surviving their first month. The last North American residential school closed in 1998.

Discover notable new fiction and nonfiction.

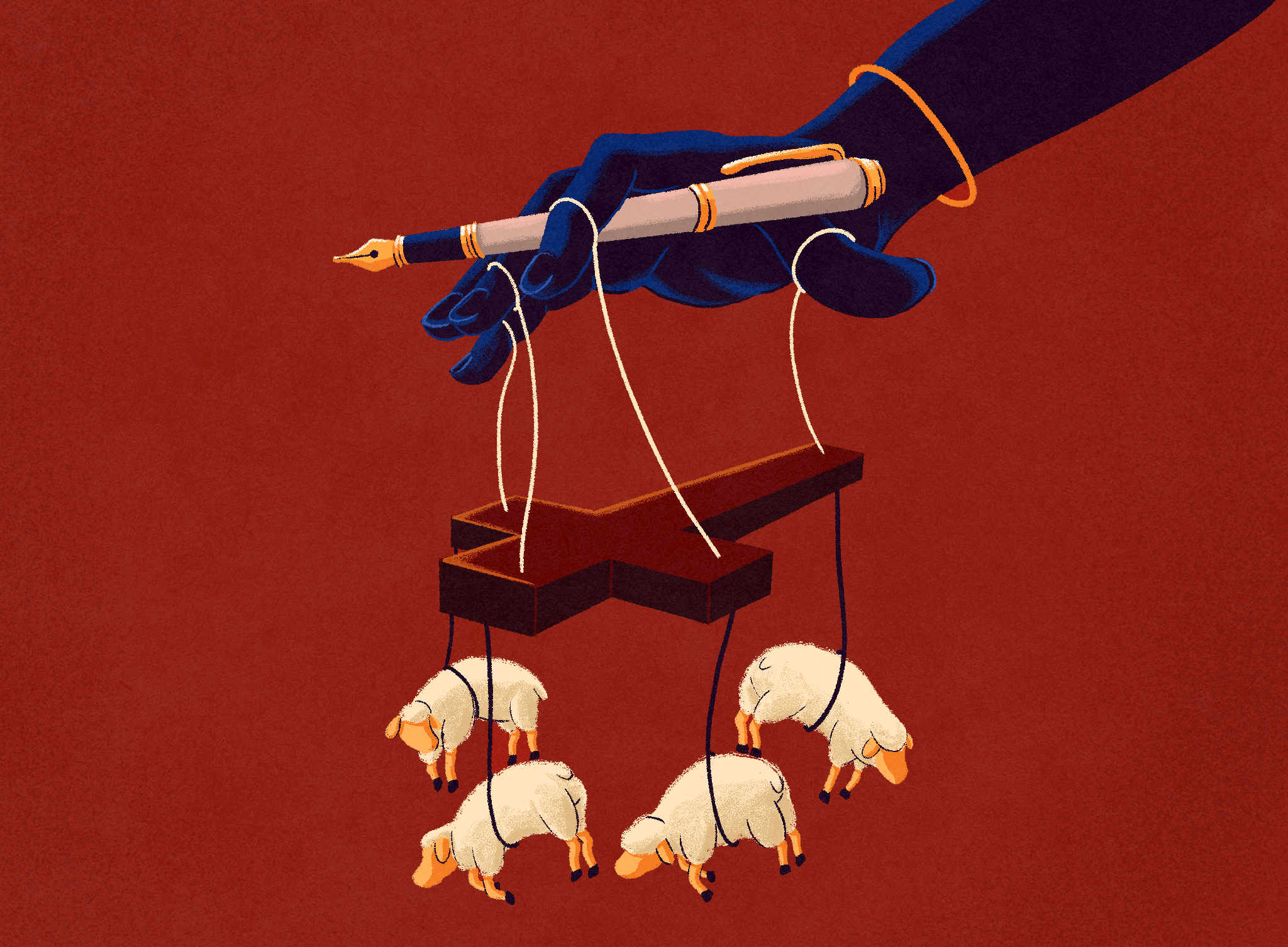

“ Wandering Stars ,” the new novel by Tommy Orange, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, spans more than a century of Indigenous history, and holds at its center the Carlisle school and its long aftershocks in the lives of a survivor and his descendants. The story follows Orange’s acclaimed 2018 début, “ There There ,” and is part of a rush of recent work examining residential schools, spurred by the discoveries in the orchard. These include the documentary “ Sugarcane ,” which just received a directing award at Sundance; the latest season of the FX television show “ Reservation Dogs ”; and the podcast “ Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s ,” which won a Pulitzer Prize last year. They join a deep and varied body of literature on the residential schools: memoirs, poetry, plays, young-adult fiction. If such accounts sought to preserve the stories of survivors and shatter the silences within families and within society, these new projects prickle with a nervy energy about what it means to handle this material at all, to push one’s fingers into the wounds. Are there silences worth protecting? What kinds of care are possible for the living and for the dead? Can the stories be told without turning them into entertainment—easily consumed, easily forgotten? What sort of action does a story make possible; what sort of healing?

Connie Walker, a Cree journalist and host of the “Stolen” podcast, knew that generations of her family had attended the schools, but it was only after the news broke about the graves at the Kamloops school that the reticence of family and friends thawed and they would sit for interviews. And, as we hear on the podcast, there was a caveat. Over coffee, a schoolmate of her father’s warns her, “This stuff that I’ve shared with you, that’s our knowledge. That’s ours. What we’ve learned. And we use that in a respectful way. This is what I call ‘ Nehiyaw .’ This is what we have learned. We don’t profiteer from it. We take care of it, where we have to pass it down. But use this in a good way. Don’t play with this.”

Second novels can be gawky creatures, sulky and strained as they try to slink out of the shadows of their predecessors. Will the second novel follow the formula, or repudiate it and chance something new? Critics seem to lie lazily in wait, ready to punish either choice. More of the same, a pity. A misjudged departure, alas .

“Wandering Stars,” calmly and cannily, has it both ways. Orange brings back the characters from the first book, where narration duties rotated among a cast of voluble and charming junkies, Internet and food addicts, criminals and aspiring criminals, deadbeat dads, dying mothers. “There’s been a lot of reservation literature written,” Orange said when his first novel came out. “I wanted to have my characters struggle in the way that I struggled, and the way that I see other Native people struggle, with identity and with authenticity.” His characters in “There There” are resolutely contemporary. They live in cities, mostly Oakland—“We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls”—and their connections to lineage and community are often frayed. Many feel insufficiently Indigenous. Thomas Frank, whose mother, like Orange’s, is white, reflects, “You’re from a people who took and took and took and took. And from a people taken. You were both and neither.” To be Native American is less an identity to be claimed and proclaimed than to be tried on, furtively, after much Internet research.

In “There There,” Orange keeps his characters distinct and recognizable, but many of them share a particular gesture. Catch them unawares and you will find them looking in a mirror or just at the darkened screen of a computer. They like to hold their own gaze, if no one else’s. Many of them share the sentiments of another character, Tony Loneman: “Maybe I’m’a do something one day, and everybody’s gonna know about me. Maybe that’s when I’ll come to life. Maybe that’s when they’ll finally be able to look at me, because they’ll have to.” It’s the desire that fuels the novel, which works doggedly to maintain the reader’s attention with its pinwheeling narration; short, swift chapters; a gun produced toward the start of the book that goes off at the end; and that sickening undertow of dread. The reader can no more escape the book than one of its characters. “I wanted to create a fast-moving vehicle to drive somebody to some brutal truth,” Orange explained in an interview.

But it is a different tempo, a different ambition—almost a different writer—we encounter in “Wandering Stars.” Where “There There” shoots forward with a linear trajectory, the new novel maunders and meanders. Repetition is its organizing principle—the repetition of pain, addiction, injury. A linear story, it seems to argue, would be a lie. The narrative spirals around and envelops the previous book. “There There” ends with an attempted robbery leading to a shooting at a powwow, and one of the central characters, Orvil Red Feather, a high-school student, is shot and badly wounded. “Wandering Stars” casts back into the past, into the lineage of his family. The book begins with the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, the Army’s mass slaughter and mutilation of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people in Colorado Territory. A teen-ager, Jude Star, narrowly survives and is imprisoned. His son, Charles, is sent to the Carlisle school. We do not see what he suffers; he shares only the ghost of a memory, of being grabbed by the back of his neck so hard that his legs give out and he falls to the bathroom floor. He discovers laudanum—it is like spooning sunshine into his mouth. When the action picks up in the present, in the wake of the shooting, we see his descendant Orvil recovering from his wound and falling into the same thrall, finding his way to opiates. Orange is as good as Denis Johnson in describing addiction’s passage into joyless duty. But it’s not merely addiction that connects these men, these generations—so many are drawn to ritual (newly invented or otherwise), storytelling, music-making. “The goal for me and my band-mates was always the same,” Orvil says. “To try and make musical loops that wouldn’t sound or feel like loops because of the way they were built, that’s the way out of a loop. Every day is a loop. Life tries the same as we try with music. Every day is the sun rising, and the sun going down, and the sleep we must sleep. I even like sleep and dreaming now. Every day is life convincing us it’s not a loop. Addiction is that way too.”

Loops are self-enclosing. The reader can see what the characters cannot—what forced migration and residential schools have prevented them from seeing and sharing. The reader can see how the addictions and terrors, as well as the capacity for pleasure and endurance, echo across the Red Feather family. The characters, cordoned off, capable only of confusing and disappointing one another, sometimes sense that profound sources of knowledge and connection have been severed. “Everything that happens to a tribe happens to everyone in the tribe,” Opal, the matriarch of the family, recalls her mother telling her. “But then she said now that we’re so spread out, lost to each other, it’s not the same, except that it’s the same in our families, everything that happens to you once you make a family, it happens to all of you, because of love, and so love was a kind of curse.”

With this expansive canvas to fill, Orange can seem perpetually out of time and out of breath. A few key characters are quick smudges, scarcely more than their signifiers—addict, nonbinary, grandmother—when, in his previous book, each character felt like a world. They sound alike, prone to parroting self-help homilies. Orange resorts to cliffhangers to stitch sections together. (“He’d never stopped worrying about Lony. Everything seemed fine. Until it wasn’t.”) And he works his motifs into tatters—holes, spiders, flying, and, above all, stars (even the bullet shards in Orvil’s body are star-shaped and prone to wandering). The book appears to suffer from the same condition as its characters; it cannot see itself, cannot see that it need not hammer home every theme every time, that it speeds where it should saunter, tarries where we need to move. And yet it expands and expands—why not throw in a subplot about a suburban pill mill?—with such exuberance that even at its most sprawling and diffuse, I wondered: Is this novel flailing or dancing?

Orange once spoke of his writing process as a practice of building portals for himself, small doors to help him find his way back into difficult sections in a draft. What if this billowy book is intended to open a series of small doors, but for the reader? It’s a shelf of books collapsed into one: for the price of a novel, here is a recovery manual; an account of trauma therapy; a guide to writing, with lists of recommended reading; a chronicle of American history that carries us from the Sand Creek Massacre to the Native American occupation of Alcatraz. Each topic is a door for the reader, and Orange insures that there will be something behind each door, something to keep. Everything the characters cannot share with one another is bound together here: the flailing and the dancing, the sorrow and the survival strategies, the sweet and the sour—like the blackberries one of their ancestors, Little Bird Woman, craves during her pregnancy. She talks, in a drowsy way, to her unborn child: “I like them tart, with that little bit of red still at their tops, or if they’re just a little hard and not so soft they come off when you pull at them and leave your fingers stained. The sweet and the sour together at once has been tasting better ever since you got big in me, so it must be you doing that.”

“Wandering Stars” talks to the future, too; it is a book about Orvil and his younger brother, Lony, and a story made for them. “Yes it would be nice if the rest of the country understood that not all of us have our culture or language intact directly because of what happened to our people,” their grandmother says. “How we were systematically wiped out from the outside in and then the inside out, and consistently dehumanized and misrepresented in the media and in educational institutions, but we needed to understand it for ourselves. The extent we made it through.”

In July, 2021, shortly after the discoveries in the apple orchard, the T’exelcemc people of Williams Lake First Nation, in British Columbia, began conducting their own investigation into unmarked graves at St. Joseph’s Mission, a former residential school. The directors of “Sugarcane,” Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie, followed the months-long process in their documentary.

It is a personal story for NoiseCat, a member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escen’ of the Secwépemc Nation. His family had attended St. Joseph’s Mission, and his father had been found abandoned there as an infant. Like many of Orange’s characters, NoiseCat grew up in Oakland, and the story that emerges is one of loops of private pain intersecting, the repetitions revealed. “You don’t fully recognize the thing that we share. Your story is someone who is abandoned but also someone who abandoned,” NoiseCat tells his father. As in the world of “Wandering Stars,” the sweet and the sour mingle. Father and son are on a quest to get to the bottom of almost unbearable truths, but their travels often have the warmth and goofiness of a buddy comedy.

What is most striking, however, is what “Sugarcane” does not do and will not show. It is a particular refusal shared, in some ways, by “Wandering Stars,” “Reservation Dogs,” and “Stolen.” The most anguished conversations—between NoiseCat’s father and his father’s mother, say—are kept off camera. In the most recent season of “Reservation Dogs,” which depicts the residential schools, the torture and death of young children is alluded to but never shown.

There is a widespread expectation that beneath silence pulses a story waiting to be told. Suffering must be spoken, we are urged. Confession expiates. It has to be coaxed out, in its anguished detail, and held in the light. But in these works, where we anticipate testimony, we receive ceremony instead. The survivors in “Sugarcane” share the outlines of their experience, and the film cuts to scenes of men praying. After difficult revelations, the survivors are brushed with feathers. It’s the inversion of what such depictions teach us to expect. Instead of a story extracted, secrets revealed, a face in close-up, we see men going into the sweat lodge, where the camera cannot follow. We see the subjects being held, and covered, the traditional ritual for cohesion and healing restored.

The characters in “Wandering Stars” have a ravenous hunger for ritual—Lony Red Feather invents his own, out of a need and a despair he doesn’t fully understand, cutting himself and burying his blood in the earth. He is trying, he explains, to forge a connection to his tribal nation, the Cheyenne, the “cut people,” as they were once known. He is not shedding his pain but attempting to move with it, make something with it. In the opening montage of “Sugarcane,” we meet the survivors, and each of them is doing the same. NoiseCat’s father is carving wood; a former T’exelcemc chief, Rick Gilbert, plays his violin, lost, like Orvil, in loops of sound. “There was unspeakable pain and loss all about us wherever we went,” Jude Star recalls early in Orange’s novel. “But with the drum between us, and the singing, there was made something new. We pounded, and sang, and out came this brutal kind of beauty lifting everything up in song.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

An Oscar-winning filmmaker takes on the Church of Scientology .

Wendy Wasserstein on the baby who arrived too soon .

The young stowaways thrown overboard at sea .

As he rose in politics, Robert Moses discovered that decisions about New York City’s future would not be based on democracy .

The Muslim tamale king of the Old West .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “ Girl .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

- Saved Articles

- Newsletters

Tommy Orange’s ‘Wandering Stars’ Traces a Family's Scars Across Six Generations

Please try again

Anyone who’s lived with someone experiencing addiction — or dealt with it themselves — knows how it can plunge entire families into chaos. The damage feels personal. While experts agree that addiction often stems from other types of suffering, we have yet to contend with how collective trauma might factor into today’s overdose epidemic.

In Oakland author Tommy Orange’s capable hands, addiction that stems from the United States’ violent past and present comes into sharp focus. Orange’s new novel, Wandering Stars (out Feb. 27 via Knopf), tells a story, a century-and-a-half long, of a family descended from Jude Star, a survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. After most of Star’s community is brutally murdered, white colonizers imprison him and subject him to violent, forced assimilation. He ends up drinking to cope with a psychic wound so deep that it ripples through six generations.

Orange himself is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes; his ancestors also survived the Sand Creek Massacre. He chose addiction as the throughline of Wandering Stars because of its impact on his own family.

“The things that affect your life are what you end up writing about or obsessing over,” he says. “I also wanted to write it in a way … that would make the reader understand and have compassion for the characters, and where addiction comes from. Sometimes it’s treated as this moral failing. … But the way that I approach it is much more medicinal — a way to cope that sort of gets out of control.”

Part One of Wandering Stars arrives in short, dreamlike dispatches from the past, where Orange switches perspective, from first to second to third person, as he gives us glimpses into characters such as Star’s son Charles, an aspiring writer. Hope glimmers throughout Wandering Stars when characters use art and storytelling to process tragedy — in Charles’ case, the unspeakable abuses at Carlisle Indian Industrial School. He eventually winds up in Oakland, where his descendants stay rooted for generations to come.

Orange’s world-building is somewhat sparse as he covers three generations across the first 100 pages. With experimental writing both poetic and poignant, it doesn’t read as straight-ahead historical fiction. The reader often ends up piecing facts together hazily, as if through clouds of smoke.

Orange’s universe becomes more vivid when we arrive in 2018 for Part Two, called “Aftermath.” There, we meet the youngest of Star’s descendants, Orvil, Lony and Loother Red Feather. (The three boys first appeared in Orange’s 2018 Pulitzer-nominated debut, There There , in which 14-year-old Orvil survives a senseless act of violence.)

In Wandering Stars , Orvil gets hooked on opioids while in treatment. It turns out the opioids also soothe the buried pain of surviving his mother’s heroin addiction and suicide, and Orvil keeps chasing the high.

About two-thirds of Wandering Stars is spent with these adolescent boys, their newly sober grandmother Jacquie — who’s just re-entered the picture after multiple disappearances — and Opal, the great-aunt who raised them. Orange gives their household so much texture that it’s easy for the reader to feel like they’re a part of this dysfunctional, lovable family. The brothers’ adolescent foolishness lends occasional comic relief, and the grandmothers’ fragile hope as they rebuild their relationship brings an anxious tenderness.

Poignantly, each character harbors inner struggles that — given Orange’s long view of history — feel as if they’ve cascaded down from the events of 1864, whether the characters consciously realize it or not.

It’s impossible to read Wandering Stars and not think about our relationship to this stolen land, and that the United States is built upon despicable violence that most of us have been conditioned to at best ignore, and at worst to glorify. Even though the subject is deeply personal for Orange, writing about it, he says, was cathartic.

“Working the language to more clearly express certain kinds of pain and weight,” he says, “frees energy, or it transforms things, in a way that feels liberating.”

Wandering Stars brings clarity to how atrocities — historical and present-day — can scar an entire lineage. That theme has the power to resonate with readers of all backgrounds, and invites us to reexamine the bigger context of our own lives. This is a book that will change you: I sobbed, unable to put it down, for the final 100 pages.

Some of Orange’s characters, like the author himself, eventually move from surviving towards healing.

“I think I’m still figuring it out,” Orange admits. “I think the way to heal is thinking about harm. How much harm are you bringing to yourself? How much harm are you bringing to others? And trying to reduce that until it’s not there anymore. And transforming that into helping yourself, helping other people. I think that’s the path of healing.”

Thanks for signing up for the newsletter.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

- Get a Free Issue of our Ezine! Claim

Book summary and reviews of Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

Wandering Stars

by Tommy Orange

- Critics' Consensus:

- Readers' Rating:

- Genre: Literary Fiction

- Publication Information

- Write a Review

- Buy This Book

About this book

Book summary.

The Pulitzer Prize-finalist and author of the breakout bestseller There There delivers a masterful follow-up to his already classic first novel. Extending his constellation of narratives into the past and future, Tommy Orange traces the legacies of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School through three generations of a family in a story that is by turns shattering and wondrous.

Colorado, 1864. Star, a young survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre, is brought to the Fort Marion Prison Castle, where he is forced to learn English and practice Christianity by Richard Henry Pratt, an evangelical prison guard who will go on to found the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, an institution dedicated to the eradication of Native history, culture, and identity. A generation later, Star's son, Charles, is sent to the school, where he is brutalized by the man who was once his father's jailer. Under Pratt's harsh treatment, Charles clings to moments he shares with a young fellow student, Opal Viola, as the two envision a future away from the institutional violence that follows their bloodlines. Oakland, 2018. Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield is barely holding her family together after the shooting that nearly took the life of her nephew Orvil. From the moment he awakens in his hospital bed, Orvil begins compulsively googling school shootings on YouTube. He also becomes emotionally reliant on the prescription medications meant to ease his physical trauma. His younger brother, Lony, suffering from PTSD, is struggling to make sense of the carnage he witnessed at the shooting by secretly cutting himself and enacting blood rituals that he hopes will connect him to his Cheyenne heritage. Opal is equally adrift, experimenting with Ceremony and peyote, searching for a way to heal her wounded family. Tommy Orange once again delivers a story that is piercing in its poetry, sorrow, and rage and is a devastating indictment of America's war on its own people.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

"A stirring portrait of the fractured but resilient Bear Shield-Red Feather family in the wake of the Oakland powwow shooting that closed out the previous book ... With incandescent prose and precise insights, Orange mines the gaps in his characters' memories and finds meaning in the stories of their lives. This devastating narrative confirms Orange's essential place in the canon of Native American literature." — Publishers Weekly (starred review) "A searing study of the consequences of a genocide ... Orange is gifted at elevating his characters without romanticizing them, and though the cast is smaller than in There There , the sense of history is deeper." — Kirkus Reviews (starred review) "Tender yet eviscerating ... There is so much life in this mesmerizing, kaleidoscopic novel ... Orange's second novel is both prequel and sequel to the striking There, There and a centuries-spanning novel that stands firmly on its own." — Booklist (starred review) "If there was any doubt after his incredible debut, there should be none now: Tommy Orange is one of our most important writers. The way he weaves time and life together, demands we remember how our history shapes us. In this novel the pain and resilience of generations are summoned beautifully. A wonderous journey and a necessary reminder." —Nana Kwame Adjei Brenyah, author of Chain Gang All Stars "No one knows how to express tenderness and yearning like Tommy Orange. With an all-seeing heart, he traces historical and contemporary cruelties, vagaries, salvations and solutions visited upon young Cheyenne people, who cope with the impossible. In them, Tommy finds the unnerving strength that results when a broken spirit mends itself, when a wandering star finds its place, when, in spite of everything, Native people manage to survive." —Louise Erdrich, author of The Sentence

Author Information

- Books by this Author

Tommy Orange Author Biography

Photo: Elena Seibert

Tommy Orange is a recent graduate from the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He is a 2014 MacDowell Fellow, and a 2016 Writing by Writers Fellow. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. He was born and raised in Oakland, California, and currently lives in Angels Camp, California.

Other books by Tommy Orange at BookBrowse

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- Early Sobrieties by Michael Deagler

- There Are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak

- Cecilia by K-Ming Chang

- Mina's Matchbox by Yoko Ogawa

- Colored Television by Danzy Senna

- Liars by Sarah Manguso

- Long After We Are Gone by Terah Shelton Harris

- Real Americans by Rachel Khong

- Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

- The Anthropologists by Aysegül Savas

more literary fiction...

Become a Member

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

Everything We Never Knew by Julianne Hough

A dazzling, heartwarming novel from Emmy winner Julianne Hough and Rule author Ellen Goodlett.

The Fertile Earth by Ruthvika Rao

A love story set against India's political turmoil, where two young people defy social barriers.

Solve this clue:

The A O M E

and be entered to win..

Win This Book

Follow the Stars Home by Diane C. McPhail

A reimagining of the intrepid woman who braved treacherous waters on the first steamboat voyage to conquer the Mississippi River.

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Tommy Orange on his new novel 'Wandering Stars'

Scott Simon

NPR's Scott Simon asks Tommy Orange about his new novel, "Wandering Stars." It is a sequel to his first, "There There," which was a Pulitzer finalist.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Simone and Her Books

An exploration through sci-fi, fantasy, and romance books

Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange // Book Review

“Wandering stars, to whom it is reserved the blackness of darkness forever.”

Here’s more about Wandering Stars

Colorado, 1864. Star, a young survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre, is brought to the Fort Marion Prison Castle, where he is forced to learn English and practice Christianity by Richard Henry Pratt, an evangelical prison guard who will go on to found the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, an institution dedicated to the eradication of Native history, culture, and identity. A generation later, Star’s son, Charles, is sent to the school, where he is brutalized by the man who was once his father’s jailer. Under Pratt’s harsh treatment, Charles clings to moments he shares with a young fellow student, Opal Viola, as the two envision a future away from the institutional violence that follows their bloodlines. Oakland, 2018. Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield is barely holding her family together after the shooting that nearly took the life of her nephew Orvil. From the moment he awakens in his hospital bed, Orvil begins compulsively googling school shootings on YouTube. He also becomes emotionally reliant on the prescription medications meant to ease his physical trauma. His younger brother, Lony, suffering from PTSD, is struggling to make sense of the carnage he witnessed at the shooting by secretly cutting himself and enacting blood rituals that he hopes will connect him to his Cheyenne heritage. Opal is equally adrift, experimenting with Ceremony and peyote, searching for a way to heal her wounded family. Extending his constellation of narratives into the past and future, Tommy Orange once again delivers a story that is by turns shattering and wondrous, a book piercing in its poetry, sorrow, and rage—a masterful follow-up to his already-classic first novel, and a devastating indictment of America’s war on its own people.

Find it on Amazon | Find it on Bookshop.org

My thoughts

I originally gave this one three stars, but after a week of thinking about it, I feel like I did this book wrong. Granted, it’s not perfect. The writing style is very disjointed, it doesn’t give a lot of that interesting backstory it starts off with, and I found myself wanting more of a lot of pieces here and there. If you’re not a fan of these elements or find it frustrating to read, then you may not like this story. But this is a character-driven novel and something these stories are really good at doing is getting characters into your head. These are characters you think about, you worry about, and you wonder about well after the final page. And the circumstances that Orvil, Lony, Loother, and the rest of the folks in Star’s family line weigh heavy on my heart weeks after reading it.

If I could check in with characters, I would. Check in and see if they’re doing okay, if they’ve accomplished their goals, if they’ve stumbled. Reading Wandering Star isn’t a prequel or a sequel to There, There , but it’s a check in. If you were thinking about the characters and how they coped with the shooting at the powwow and then how their lives turned out then this is the book for you. And I know Tommy Orange didn’t write this book to assuage the mental and emotional state of his readers, but it does help with it. Tommy Orange was just obliging to let you know.

While the historical bit of the book (the prequel) was truncated, it was the most fascinating. Hearing the history of Orvil’s family starting from Star, his time as a prisoner of war in Florida, how he was forced to assimilate to the “American” culture, how it didn’t phase Star, but somehow fractured his family line to the point where the generations to come wouldn’t know anything about him. How Richard Pratt, the white guy who made this all happen, thought he did the Native Americans a service when he only aided in them losing their sense of identity that only expands to present day Redfeathers and his lack of knowledge of the Cheyenne people. It reminded me a lot of Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi and how fractured history is for the characters in that book as well.

And of course, there’s a level of artistry when it comes to Tommy Orange’s books. You’re not going to read a linear story. It jumps from character to character learning bits and pieces of the fractured people they have become and the methods of coping with those fractures. Lony and his obsession with the energy coming out of our abdomens (shout out to Donnie Darko, which was an obsession for me when I was a teenager) then Loother and his relationship with girls, to Orvil and how he’s coping with being shot while doing his dance at the powwow (spoilers, not good). Using various perspectives and POVs, you’re not just reading a story but experiencing an entire ecosystem of cause and effect of history touching reality and the present pushing towards the unknowable future. It’s almost beautiful.

Overall, an intriguing story that answers “the after.” What happens after you’re shot? What happens after you’ve been whitewashed? What happens after your teens? It’s such an incredible way to share this story and like I said, you’ll be rooting for this family the entire time.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

Tommy Orange Is Trying to “Undo the White-Dominant American Narrative” With His New Book, Wandering Stars

Tommy Orange wasn’t ready for the massive success that came with the 2018 release of his debut novel, There There . The 42-year-old Cheyenne author went from relative obscurity working within the thriving Native American community in his hometown of Oakland, California, to becoming a leading voice in contemporary Indigenous literature seemingly overnight. That New York Times bestseller weaved together the stories of 12 Native characters to masterful effect, earning Orange accolades like an American Book Award, the PEN/Hemingway Award, the John Leonard Prize, and a Pulitzer Prize finalist nod.

His highly anticipated follow-up, Wandering Stars (out February 27), is at once a prequel and a sequel to There There. The tome takes readers back to the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, a controversial surprise attack where the US Army brutally murdered around 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho people. It then fast-forwards to the next generation’s detention at Pennsylvania’s infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School , which aimed to “kill the Indian” through forced assimilation. It then leaps ahead to the next generation’s experiences in the aftermath of the powwow shooting that concludes There There.

A lyrical storyteller, Orange addresses the many atrocities tribal communities have faced in what he calls “America’s longest war” waged against Native peoples as well as the many enduring effects of colonialism, such as outsized poverty , addiction , suicide , and violence . In doing so, he brilliantly illustrates how Indigenous individuals are seeking a sense of self and belonging by piecing together the fragments of their familial history, while also grappling with intergenerational traumas.

Although he’s not willing to serve as a spokesperson on behalf of Native America at large—after all, Indigenous cultures are not a monolith, with 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone—Orange has embraced his undeniable role in bringing Native issues to the forefront. In conversation with Vanity Fair, he talks about the current Indigenous renaissance, the importance of authentic representation, and the complexities of Indigeneity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity .

Vanity Fair: Native Americans often bear the burden of educating others about the atrocities that Indigenous peoples have endured. How do you handle that responsibility?

Tommy Orange: After spending a long time living with people’s incorrect, often offensive versions of what happened historically to Native people in this country, I think writing There There and now Wandering Stars is part of handling that responsibility. I’m trying to tell it in a way that reflects what we know and what historians know to be true. Because historians actually look deeper into history, whereas the general population gets the Pilgrims and Indians story and that’s basically it. I don’t know if it’s any better now, but when my son was in first grade at a public school, he came home with this pamphlet about Pilgrims. We actually changed schools, because we didn’t want him even interfacing with that.

I think what else you’re getting at, though, is when I’m in public and people ask stupid questions or say stupid things, how do I handle the responsibility of being a spokesperson for all of Native America—which is a ridiculous position to be in, because I can’t be that. In the past, sometimes I would get angry or shut down, but now I try to unpack what people say. There have been instances when people are intentionally hurtful, but a lot of times, it’s just ignorance.

Like the use of the word “Indian.” People don’t know what to call us, and I generally explain that we want to be referred to by our tribes. If you’re not Native, don’t use the word “Indian,” because it has been used to harm us. Native people use it because it’s the only word we had for ourselves for a long time, and now we’ve reclaimed it.

I was actually doing an author Q&A session where I said this very thing, and not two minutes later, somebody asks a question and calls us “Indian” in the question. I had to stop them and again explain that there’s a lack of respect for us at a very basic level, because our dehumanization has been institutionalized in our schools. It’s not that I’m genuinely hurt by the word—it’s about lessening the harm and understanding the context of how it has been used to reduce us.

Wandering Stars connects past to present to future in a way that reflects Indigenous intergenerational trauma. Why was it important to tell these stories on a continuum?

Originally, I actually didn’t want to write anything historical, because that’s the way Native people have been portrayed for a very long time. We’re stuck in history, which isn’t helpful for others to understand our complexity. But then I saw this newspaper clipping about Fort Marion [a prison where the US government exiled dozens of Native men in 1865], which led me down this rabbit hole.

In my research, I was looking at the names of the prisoners, and two stuck out. One was Star, because I had already thought of the book title and had a character with that name. The other one was Bear Shield, a name from the There There family that I was also focusing on for Wandering Stars.

So that was just a really surreal moment. I realized I wanted to show how history shows up in the present and write this family line that would end in the aftermath of the powwow in There There. Oscar Hokeah ’s Calling For A Blanket Dance does this generational building that I really loved, and reading that book convinced me to attempt to use this story structure for Wandering Stars.

There There thrust you into the spotlight as a leading voice in contemporary Native literature. Did you feel pressure following up on the success of your breakout debut?

Absolutely. I can say fairly objectively that the success of There There was pretty massive, with the book sales and critical acclaim. Then with a sophomore effort, there’s this idea that you have to do equal or better, or else it’s going to be seen as a failure. So in addition to the regular self-loathing and doubt that are part of the writing process, there were all these new voices in my head.

I started writing Wandering Stars three months before There There came out. So by the time it comes out, it will have been six years since I began, which is about the same amount of time There There took. Writing a novel is a hard, complicated process, and in my experience, you can’t just push through it. There are some people who can write a lot of books and write them quickly, and I think everyone sort of secretly hates those people. [laughs] But I do hope I’ve figured out my process a bit better so that my third book doesn’t take six years.

How does your own Indigeneity, including feelings of being “ not Native enough ,” factor into your writing?

I think it’s something I will always write about. One question I’ve gotten countless times is, “Are you always going to write about Native people?” And the underlying question is really, “Can’t you just write about white people?” There will always be some white people who want stories about themselves, because that’s what they’re used to.

When I first started writing fiction, it was pretty experimental, stream of consciousness, maybe attempting philosophical, probably fairly cringe-inducing. But as soon as I started including my life details in my fiction—which is not to say that I’m writing thinly veiled autobiographical fiction, but rather just dealing with identity—it came with all of my experience and baggage.

As a [Cheyenne and white] biracial person, I’ve thought about being Native and not being Native enough a lot. So my characters are inevitably going to be thinking about what it means to be a Native person in this country too. My third book isn’t related to the first two, but there are still characters dealing with this in an intense way. It’s inextricable from my writing, and I don’t think that’s ever going to change. People write about what matters to them and what they need to process, and that’s been a big part of my life experience.

How do you approach delving into heavy topics like colonialism, genocide, and oppression? Do you practice self-care as part of your writing process?

I think writing about these things is part of self-care, as weird as that sounds. Because I’m trying to think about them in a way that makes them clearer. The revision process is all about clarity: Is what you’re writing about clear to the reader? Are you saying it in a way that’s compelling, that’s imbuing it with meaning and artful care? All of that helps, because the heavy stuff is there whether I process it or not. That’s not to say that writing is therapy, because for me it’s definitely not. I also run a lot as part of my routine.

I’ve dealt with a lot of trauma and addiction in my family, so life has always been heavy for me. Writing about these topics doesn’t feel like a burden, although I think it makes a lot of people uncomfortable because we teach history in this nationalistic way that’s not really helpful for anything other than creating obedient citizens who love their country. I’m trying to undo the white-dominant American narrative.

Since There There debuted, we’ve experienced a racial reckoning and a Native renaissance. When it comes to authentic representation and celebration of Indigenous cultures, do you think we’ve made meaningful progress?

I would say I’m cautiously optimistic, because we’ve seen this before. The fact that there have been multiple renaissances means that there has been multiple deaths of interest in us. There was a spike in interest after the Civil Rights Movement , then another one after Dances with Wolves swept the Oscars , as ridiculous as that sounds. The [2016] Standing Rock protests were really the beginning of this newest renaissance, where it took our elders—who were praying for clean water—being sprayed with ice-cold water in the middle of a North Dakota night to wake people up to our situation. So I just hope the interest doesn’t die out again.

But there’s a lot to be excited about, like Reservation Dogs having Native people not only in front of the camera, which we’ve seen before, but also behind the camera and in the writing room. Lily Gladstone being nominated for an Oscar is also a huge moment on a huge stage, and I hope that leads to more people taking risks with us in ways they wouldn’t have before. I guess maybe There There did that too. Because ultimately this is an industry and there are financial risks when it comes to works of art.

I don’t mean to sound dismal, because what’s happening is unprecedented and really amazing. But we’re also looking at a presidential election year and the possibility of a very anti-Native leader getting another term, which could be really detrimental to us. Still, I think it is a time to celebrate—and there’s more coming from a lot of creative Native people who are doing really exciting things.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

DNC 2024: Live Updates From the Democratic National Convention

September Cover Star Jenna Ortega Is Settling Into Fame

Listen Now: VF ’s DYNASTY Podcast Explores the Royals’ Most Challenging Year

Exclusive: How Saturday Night Captures SNL ’s Wild Opening Night

Inside Prince Harry’s Final Showdown With the Murdoch Empire

The Twisted True Love Story of a Diamond Heiress and a Reality Star

Kate Nelson

Royal watch.

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Book Review: Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

Your heart, that place you don’t even think of cleaning out. That closet stuffed with savage mementos.

-Louise Erdrich, Advice to Myself

Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars is an ambitious family saga that is both a prequel and sequel to his brilliant debut novel, There There . It follows a family for over 150 years, from Jude Star escaping the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 to the Bear Shield/Red Feather family in present day Oakland. In the family’s struggles against institutionalized violence, genocide was only the beginning. Each generation inherits the trauma of their ancestors while facing fresh injustices. The government-sponsored erasure of Native American identity, cultures, languages and beliefs doesn’t completely strip them of their heritage, but what survives is fragmented and incomplete. Star and his descendants try to rebuild their shattered identity, either by reconstructing the pieces or by replacing them with other things: sometimes art, sometimes addiction, often both.

The book is divided into three sections covering seven generations of the family. Part One spans 150 years, starting with the Sand Creek Massacre. Parts Two and Three start in 2018, following the Bear Shield/Red Feather family. Given the vast difference in time periods these sections cover, it’s no surprise that the pacing and style change drastically from one to the next. Part One is episodic and reads like a combination of diary entries and historical commentary. Parts Two and Three are more comfortably literary, exploring the thoughts and motivations of the characters much more deeply. Part One can cover several decades in a chapter. Chapters in Part Two or Three rarely exceed more than a year, often lingering on a single day.

Had Part One been written like the rest of the novel, it would have tripled the size of the book. But that wouldn’t be hard to defend. It tells important stories, showing people surviving governmentally-condoned murder and erasure of their culture. As is, this section may lose readers because, on an individual level, the personal narratives feel rushed and characters disappear or die before there’s time to know them well enough to mourn them. Still, perhaps that’s intentional. This style and pacing could be a kind of nod to ancient texts, with fragmented characters like the papyrus fragments containing parts of Sappho’s poems. It would certainly fit the theme.

That said, the opening line to the novel and Jude Star’s story is magnificent: “I thought I heard birds that morning time just before the morning light, after I shot up scared of men so white they were blue.” The peaceful song of the birds is shot down by the appearance of the white/blue men. This use of color not only invokes the blue uniforms of the Union soldiers raiding Cheyenne camps, it also merges their skin and with their clothes. The soldiers become otherworldly and eldritch, a horde of Lovecraftian monsters mindlessly consuming an entire community.

Is this interpretation a stretch? Writers often write what they know and it’s no historical accident that Native American horror is currently blossoming. During a talk at the Festival America in Vincennes – France, the Cree writer Billy Ray Belcourt said that white North Americans rarely understand that Native Americans are navigating a post-apocalyptic world. The opening chapter of Wandering Stars , depicting Jude Star’s survival of the Sand Creek Massacre and the subsequent months, illustrates Belcourt’s statement wonderfully.

Sometimes it felt like the world had ended and we were waiting for the next one to come. More often it felt like I was waiting for the sounds of war to come back again, for the first light of the sun to bring with it blue men come to kill and scatter us again, thin us out across the land like the buffalo, chase and starve and round us up like I’d heard by then they were doing to Indian people everywhere. We saw and ate many strange things going around together looking for our people.

After the apocalypse, survival comes first. This could explain why many characters’ stories in Part One rush with such speed to their end. This is the world of brief lives and struggle that Jude Star and his descendants live in. Much modern literary fiction focuses on interiority and identity. But rarely are characters stripped of so many of the institutions that compose identity: family, economy, culture, religion and language. For Jude Star, the Sand Creek Massacre shattered all those things. The style and pacing of Part One reflect the advances and reversals that his descendants experience as they fight to reconstruct their heritage and themselves.

Once we reach the Bear Shield/Red Feather family, the pacing slows, giving an impression of a wider psychological breadth for the characters. But the impact of their ancestors’ lives is ever-present, and with it the fear that their stories will be cut short by addiction and violence. We first see Orvil Red Feather looking up “what other kids on the internet had to say about surviving a shooting.” Recovering from a gunshot himself, he’s prone to nightmares and starts taking more painkillers than necessary. He’s just in high school, but this ancestral cycle of tragedy already seems to have drawn him in.

Everyone in Orvil’s family is navigating through their trauma. Opal, the Red Feather boys’ guardian, tries to keep them safe while managing serious health issues. Jacquie, Orvil’s grandmother, is a recovering alcoholic. But particularly terrifying is Orvil’s youngest brother Lony, a sweet little boy who’s cutting himself and inventing blood ceremonies to reconnect with his heritage after he reads on the internet that “the name Cheyenne meant the cut people.” Lony approaches self-mutilation with the matter-of-factness of a young boy, a bartering logic that would appeal to an impressionable child: If he gives a piece of himself, the universe will make his family whole and save them from more pain.