Wander-Lush

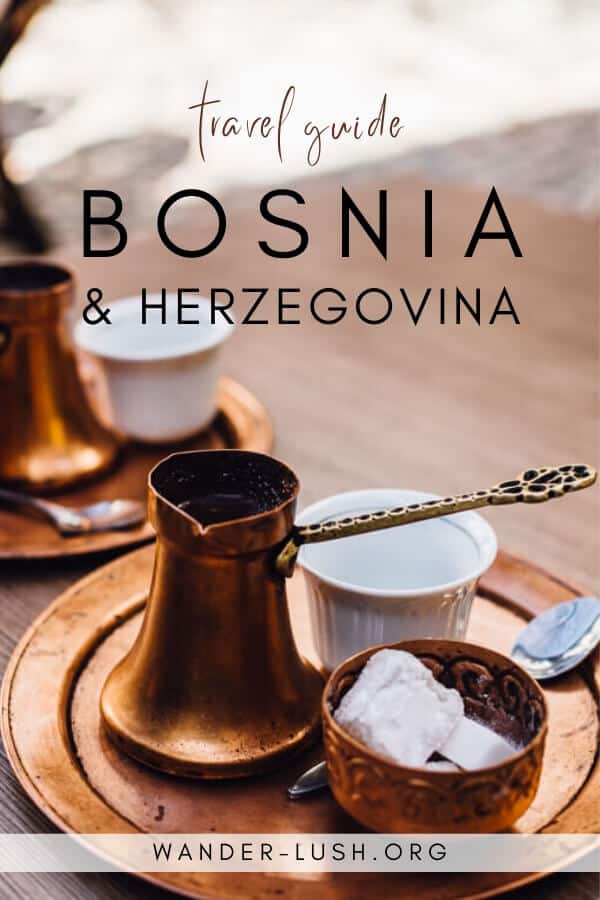

Explore Bosnia & Herzegovina: The Ultimate Bosnia Travel Guide

- Europe / The Balkans

When you go to Sarajevo, what you experience is life. Mike Leigh

Why you’ll love Bosnia and Herzegovina

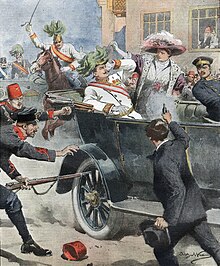

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH for short) is often associated with loss and death. From the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand which set WWI in motion, to the Siege of Sarajevo and the Srebrenica massacre, BiH has long been viewed as a nation torn apart at the seams. But now more than ever, it’s equally a place of new beginnings and budding creativity – a place where you can feel life itself tingling on your skin.

In 1992, citizens voted in a monumental independence referendum and Bosnia and Herzegovina gained her independence. The dotted lines of autonomous republics, the intricate political system (often named the most complex in the world), and the very presence of the ‘and’ in the country’s name are a clue to the kind of diversity and contrasts you can expect today.

If there’s one thing I learned after five weeks travelling around BiH, it’s that the warmth of the people and the illustrious beauty of the landscape are the strongest uniting forces.

Bosnia travel essentials

Please note: Some of these links are affiliate links, meaning I may earn a commission if you make a purchase by clicking a link (at no extra cost to you). Learn more .

April/May or October/November (spring/fall shoulder seasons).

How long in Bosnia?

2 full days for Sarajevo; 5-7 days for the highlights; 10 days to see everything.

Daily budget

35-50 USD per person per day (mid-range hotel; local meals; bus fares; museum tickets).

Getting there

Fly into Sarajevo or Tuzla; drive/bus/taxi from any neighbouring country.

Visa-free for most passports (stay up to 90 days).

Getting around

Hire a car; use intercity buses and vans.

Where to stay

Hostels, family-run guesthouses or hotels.

Tours & experiences

Market tours, UNESCO sites and wild landscapes.

Things to do in Bosnia and Herzegovina

In Sarajevo , BiH’s capital city, the line where Asia stops and Europe begins (or is the other way around?) is literally drawn in the sand. A plaque on the pavement separates the Austro-Hungarian-built part of the city, with its market halls and plasterwork facades, from the Ottoman quarter, with its public fountains and singing minarets.

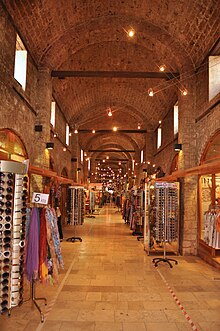

Sarajevo’s Old Bazaar , Bascarsija , is pure magic. As you dart between tea houses, carpet shops and Buregdzinicas (bakeries specialising in burek ), you move to the rhythm of tradesmen who still pound bronze with the same fervour as they did centuries ago.

As you cross the stone bridges in Mostar , Visegrad and Konjic , you begin to understand that not only is each one a proxy for a devastating chapter of Balkan history (which every traveller must take the time to learn about), it’s also a symbolic bridge between past, present and future.

From Jajce , the city with roaring waterfall at its centre to Pocitelj , an almost-abandoned Ottoman town, Banja Luka , the country’s second city to the sweet Trebinje ; between the Dinaric Alps , the Pliva Lakes and the ambling River Drina , Bosnia and Herzegovina has a way of making you feel alive.

Explore Bosnia and Herzegovina

Discover all the best things to do in Bosnia with my latest travel guides.

Sarajevo Through the Lens: 42 Magical Photos of Bosnia & Herzegovina’s Capital

How to Spend One Day in Mostar: 24 Hours in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Most Captivating City

The Best Bosnian Food: 20 Delicious Things to Eat & Drink in Bosnia and Herzegovina

12 Things to do in Banja Luka, Bosnia & Herzegovina’s Second City (Republika Srpska)

12 Best Sarajevo Day Trips for History, Nature & Culture

5 Things I Learned on a Sarajevo Food Tour

Pliva Lakes & Watermills: A Guide to Visiting From Jajce

A Quick Guide to Jajce, Bosnia & Herzegovina’s Cascade City

Mostar to Pocitelj: A Complete Guide to Visiting the Ottoman-era Open Air Museum

An Epic Day Trip from Sarajevo to Visegrad, Borak Stecci and Mokra Gora

My bosnia favourites.

Via Dinarica Trail (Slovenia to Kosovo via BiH).

Must-eat meal

Tufahija (baked apple) with a Bosnian coffee.

local experience

Watching the sunset over Sarajevo from Bijela Tabija.

best souvenir

A copper tray or coffee pot from the Sarajevo Old Bazaar.

- 1.1 History

- 1.2 Orientation

- 1.3 Climate

- 2.1 By plane

- 2.2 By train

- 2.5 By thumb

- 3.1 On foot

- 3.2.1 By tram

- 3.2.2 By bus

- 3.3 By bicycle

- 3.4 By taxi

- 3.5 By shared electric scooter

- 4.1 Baščaršija

- 4.2.1 History and archeology

- 4.2.2 War memorials

- 4.3 Administrative buildings

- 4.4.1 Islamic

- 4.4.2 Christian

- 4.4.3 Jewish

- 4.5.1 Goat's Bridge

- 4.6 Vratnik

- 4.7 Olympics

- 5.1 Recreation parks

- 6.1 Baščaršija

- 6.2 Shopping malls

- 7.1.1 City centre around the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

- 7.1.2 City centre around the Vječna vatra memorial

- 7.2 Mid-range

- 7.3 Splurge

- 9.2 Mid-range

- 9.3 Splurge

- 11.1 Emergency services

- 12 Stay healthy

- 14.1 Embassies

<a href=\"https://tools.wmflabs.org/wikivoyage/w/poi2gpx.php?print=gpx&lang=en&name=Sarajevo\" title=\"Download GPX file for this article\" data-parsoid=\"{}\"><img alt=\"Download GPX file for this article\" resource=\"./File:GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\" src=\"//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\" decoding=\"async\" data-file-width=\"20\" data-file-height=\"20\" data-file-type=\"bitmap\" height=\"20\" width=\"20\" class=\"mw-file-element\" data-parsoid='{\"a\":{\"resource\":\"./File:GPX_Document_rev3-20x20.png\",\"height\":\"20\",\"width\":\"20\"},\"sa\":{\"resource\":\"File:GPX Document rev3-20x20.png\"}}'/></a></span>"}'/>

Sarajevo is the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina , and its largest city, with 420,000 citizens in its urban area (2013). Sarajevo metropolitan area that has a population of 555,000 also includes some neighbourhoods of "East Sarajevo" that are a part of Republika Srpska . Sarajevo is very tourist friendly, especially pedestrian area in the Old Town in the centre of the city.

Sarajevo is one of the most historically interesting and diverse cities in this part of Europe. It is a place where the Western and Eastern Roman Empire split; where the people of the Roman Catholic west, Eastern Orthodox east and the Ottoman south, met, lived and warred. It is both an example of historical turbulence and the clash of civilizations, as well as a beacon of hope for peace through multicultural tolerance. The city is traditionally known for its religious diversity, with Muslims, Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Jews coexisting here for centuries. Additionally, the city's vast historic diversity is strongly reflected in its architecture. Parts of the city have a very Central-European look, while other parts of the city, often blocks away, have a completely distinct Ottoman, some Soviet-like or Socialist modernism feel.

Some important events in Sarajevo's history include the 1914 assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which led to World War I ; the 1984 Winter Olympics; and the 1992-1996 siege.

The city has physically recovered from most of the damage caused by the Yugoslav Wars of 1992–1995, although bullet holes can still be found in some buildings. Sarajevo is a cosmopolitan European capital with a unique Eastern twist that is a delight to explore. The people are very friendly, be they Bosniaks, Croats, Serbs or anyone else. There is little street crime, with the city ranking as one of the safest in Southeastern Europe.

Orientation

The city of Sarajevo stretches west–east along the river Miljacka; the main arterial road and tram routes tend to follow the west–east orientation. It is set in a narrow valley, surrounded by mountains on three sides.

Most tourists spend a lot of time in Old Town ( Stari Grad ). The eastern half of Old Town consists of the Ottoman-influenced Bascarsija ( BAHS CHAR she ya ; etymologically baš (head, main), čaršija (bazaar, trading area) in Turkish), while the western half showcases an architecture and culture that arrived with Austria-Hungary, symbolically representing the city as a meeting place between East and West.

- 43.85935 18.43049 1 Tourist Information Centre , Sarači 58 , ☏ +387 33 580 999 , [email protected] . ( updated Sep 2017 )

- [ Visit Sarajevo

- "Sarajevo Navigator" is an online guide magazine in English and Bosnian, the latest issue being March 2019.

Sarajevo has a humid continental climate, since mountains surrounding the city greatly reduce the maritime influence of the Adriatic Sea. Summers are typically hot (record high of 41 °C in 2008) with an average of 46 days per year above 32 °C, while winters are snowy and cold with an average 4 days per year below -15 °C. Rain can be expected in every season, with an average of 75 days of precipitation per year, which in winter often falls as snow.

This is Bosnia's principal airport, hemmed in by mountains and fog-prone, so flight delays are common in winter. The only passenger terminal is Terminal B; it's closed overnight 23:00–05:00. In the groundside main hall (after customs on arrival, before security on departure) there are currency exchange booths, car rental desks, a bookshop that sells local SIM cards, and a fast food area upstairs; there's no luggage storage. Airside is small, with a cafe and duty free shops accepting major currencies. New terminal facilities are under construction, to open in 2021. About 1 km away, walkable by the route to the trolleybus (below) then keep straight on, is the East Bus Station for destinations in Republika Srpska.

The most important hub connections are from Frankfurt (by Lufthansa), Vienna (by Austrian), Istanbul (by Turkish Airlines), Dubai (by flydubai) and Doha (by Qatar Airways) as well as flights to neighbouring countries (Belgrade by Air Serbia and Zagreb by Croatia Airlines) amongst others. Service to London-Luton is operated by Wizz Air, and to London-Stansted from April to October.

While you're at the airport, consider visiting the Tunnel of Hope Museum ( Tunel Spasa ). This saves you a trip from city centre later on, though you'll probably have to drag your luggage along. The museum is southside of the runway (the terminal being north), which they tunnelled beneath in 1993 to create a lifeline to the besieged city.

Getting there and away :

- By bus – Centrotrans bus runs daily between airport and Baščaršija in city centre. It runs roughly hourly 05:30-22:00, timed to connect with flights, taking 20-30 mins. A one-way ticket is 5 KM, return 8 KM, the first bag (up to 23 kg) per person is included and each extra bag is 5 KM. You pay on boarding the bus. It stops on request at central bus stops, which may not be specifically marked for the airport bus but they're usually next to tram stops.

- By taxi – Taxis are notorious for scams! To the city centre should not exceed 20 KM, although some drivers try for double that from foreigners. Flagfall is 1.90 KM then it's 1.20 KM per km for 6–7 km; any "airport supplement" is bogus. Some drivers will refuse to use the meters; insist on them, and if they don't, then walk away. One scam is to wave a "fixed price list" at you, but it's just the product of a greedy imagination. Your hotel may offer an airport transfer, with rates varying from the competitive to the silly. A further option is to walk through Dobrinja as described below to pick up a taxi, though the saving on an honest fare is small.

- By trolleybus – This involves a walk of 600 m through the nearby neighbourhood of Dobrinja to reach the stop on Bulevar Mimara Sinana. You might want a map or a compass: the general direction is northeast with the terminal directly behind you, but it involves a zigzag. You exit the airport at the main gate onto Kurta Schorka highway. Turn right (southeast) and walk 200 m, there's no sidewalk. Take the first left, Andreja Andrejevića, and cut through residential Dobrinja passing near Hotel Octagon. Emerge onto the main road and turn right (again southeast) along Bulevar Mimara Sinana. On the opposite side (with westbound traffic) after 200 m, before you reach Mercator Center, is the bus stop Dobrinja škola B. Trolleybus 103 runs every 6 – 7 minutes daytime to Trg Austrijski, in the centre on the south riverbank, taking 25 min; walk across the Latin Bridge to come into Old Town. (Don't take the 107 or 108 if you're aiming for Old Town.) The fare is 1.80 KM, pay the driver, and note there are frequent ticket inspectors.

Tuzla Airport is another way in, as it has budget flights by Wizz from across Germany and Scandinavia. The airport is 120 km north of Sarajevo. An airport bus runs direct from Sarajevo to meet the Wizz flights, taking 2 hours and costing €22 each way. Or you can travel via the frequent standard buses to Tuzla, taking a leisurely 3 hours.

- 43.86028 18.39904 2 Sarajevo Railway Station ( Nova željeznička stanica ), Put života 2 ( near Avaz Twist Tower ), ☏ +387 33 65 53 30 . This communist-era station is in a dilapidated state, with few trains and lots of down-and-outs, though it's reasonably central in this strung-out city. The ticket office is cash only and they laboriously write out tickets by hand, so service is slow. There are toilets and cafes. Staff at the information desk speak good English and their stock reply to many enquiries is to try the bus station next door: this is good advice. ( updated Jul 2019 )

The only international train to/from Bosnia runs from Ploče in Croatia on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays via Mostar (€12). Tickets purchased onboard the train from Ploče (reservation not needed or possible but Interrail/Eurail accepted) detaiils on the Croatian Railways Website . Journey time is 3 hours.

The railway route you're most likely to use is the scenic Čapljina - Mostar - Sarajevo, with two trains a day, departing from Sarajevo at 07:15 and 16:49 and taking around 2 hours to reach Mostar. Three trains per week extend south of Čapljina into Croatia and the port of Ploče (which has transport to Dubrovnik, Split and the Adriatic islands) during summer months.

Coming from Zagreb or further west an alternative is to take a local train at 09:00 to Hrvatska Kostajnica, arriving 10:45: see Croatian Railways timetable (around €8). You're now 3 km from the Bosnian borderpost, either take a taxi, or walk south into town then east and cross the river by the first bridge. Once you've entered Bosnia, find a taxi to Banja Luka , 100 km southeast, costing around 100 KM and taking maybe 90 mins. You'll reach Banja Luka in plenty of time to catch the 15:49 local train to Sarajevo via Zenica , arriving by 20:41 (fare around 26 KM). When checking the Bosnian Railways website , use the timetable menu not the ticket menu, as the latter only offers the main towns and bookable trains. For the reverse journey, be on the 10:15 train from Sarajevo to Banja Luka in order to make the 19:15 from Hrvatska Kostajnica and reach Zagreb at 21:00. And confirm that your taxi driver has agreed to take you to the correct Kostajnica on the Croatian border (ie north-west, a printed map may help).

If your accommodation is in the west of the city, e.g. the Ibis Styles Hotel, then coming from Banja Luka you could change at Zenica for the local train to Sarajevo, which also stops at 43.851682 18.346417 3 Alipašin Most on Safeta Zajke. But it doesn't save much time or effort. The trains from Čapljina and Mostar trundle through this station without stopping.

There are two bus stations in Sarajevo, Main Station for most long-distance services and East Station for Serbia and towns in Republika Srpska.

On all intercity buses you pay a fee for luggage, usually 2 KM or €1 per piece (as of July 2024). The driver will insist on exact change in one or the other currency pretty much at random, and then get picky about the denomination of the exact change you give him.

Major bus routes within the country are to Tuzla (hourly, taking 3 hours, fare 11 KM), to Mostar via Konjic and Jablanica (hourly, taking 2 hours 30 min, fare 14 KM) and to Banja Luka via Zenica (every couple of hours, taking 3 hours, fare 11 KM.)

- 43.82377 18.35649 5 East Bus Station ( Autobuska stanica Istočno / Lukavica ) ( away west, thanks to the bitter geography and politics of this region ). It's in East Sarajevo in Republika Srpska, and the route from central Sarajevo has to sweep west to get round the hills then approach south then eastwards near the airport. It has better connections to Serbia than Main Station; both stations have buses to Montenegro. The main services are to Belgrade , Novi Sad , Herceg Novi and Nis and also Zvornik for stop-over connection to Srebrenica . Routes within the country are to Bijeljina, Kalinovik and Trebinje not far from Dubrovnik. ( updated Mar 2023 )

To reach East Station, take trolleybus 103 from Austrijski Trg to the end and then walk for 400 meters, or a taxi for around 15 KM. There are no controls to cross into Republika Srpska, it's just like crossing any internal border. There's not much at the station except a ticket counter and the obligatory cafe/grill. Travellers reported harassments by a drunk guy hanging around at the east bus station (see e.g. Google Maps Reviews).

Sarajevo East Station asks you to pay a station tax which is 2 KM per person (as of July 2024). Insist on your receipt that indicates the 2 KM as the staff usually tries to scam tourists and keep the money for themselves or asks for twice the price.

East Sarajevo has cafes, shops and ATMs, e.g. in TOM shopping centre 200 m southwest along Radomira Putnika.

The main route from the west is past Zagreb east on E70, then south on E661 to enter Bosnia and towards Banja Luka thence Sarajevo via the A1 highway from Zenica. You can also reach the city from the East via the suburbs of Ilidža or from the north via M18/A1 from the direction of Tuzla.

Hitching is easy to moderate, though make sure your sign is in the local language. Sarajevo is a long, thin city: if you can't get a lift into the centre, at least get yourself dropped by the tram tracks.

Sarajevo is a medium-sized, beautiful city with many landmarks. Getting lost is always possible, but much less so if you have a map; however, getting lost in Bascarsija's winding streets can be part of the fun, and may reveal some interesting surprises.

Very good free maps can be obtained from the tourist information office, shopping centres and hotels. Some bookshops may also sell printed maps of the city. Map apps on a smartphone are particularly useful.

Asking Sarajevans for directions is an exercise in futility. People might not know the names of streets a block from the building they've lived in all their lives. Taxi drivers can't be expected to find anything other than the most obvious addresses unless you tell them where to go, in Bosnian; showing the driver on your map may be necessary.

Avoid driving in the Old Town. The steep and narrow streets, with a one way system, means you are likely to get lost and possibly damage your car. Also, it is next to impossible to find a parking spot.

Otherwise, a car might be invaluable to reach the sights farther away from the city center, especially East Sarajevo which belongs to Republika Srpska.

In Sarajevo, street signs are few and far between, and small and on the sides of buildings too far away to see when you're standing on a street corner. Building numbers are more or less consecutive. The city is mostly walkable, especially the city centre and the part of the city which is built on the slopes of Mt. Trebević.

By public transport

Sarajevo's tram network operated by KJKP GRAS is among the oldest in Europe, and it looks it. A single line runs east from Ilidža passing within 2 km of the airport: an extension to the airport has been planned and intermittently constructed since the 1990s. It runs up the middle of the main highway into the city, with a spur north (Trams 1 & 4) to the main railway and bus stations. At Marijin Dvor it divides into an anti-clockwise loop, same direction as the traffic flow. All trams go east along Hiseta and the riverbank through Baščaršija (Old Town) as far as City Hall. Here they loop to return west along Mula Mustafe Bašeskije (a few blocks north of the river) and Maršala Tita to Marijin Dvor. Only Tram 3 runs the entire line out to Ilidža, the others go part route, e.g. the 1 & 4 terminate at the railway station. The length of the route is around 12 km. Old trams from Amsterdam were donated to Sarajevo and can still be seen touring the city, with the Dutch stickers still on it.

Buy tickets in advance from kiosks labeled tisak, duhanpromet, inovine on the street (1.60 KM) or from the driver, where they cost slightly more (1.80 KM, paid in cash). Validate your ticket immediately on boarding: it's only good for one trip, with no transfers. A day card for unlimited travel on all local public transport in Zone A costs 5 KM. There are frequent ticket inspections: if you can't reach the validator because the tram is too crowded, then don't board. If you are caught without a valid ticket, you will be escorted off and fined 26.50 KM.

You would only use these for the few sights or accommodation well off the tram route, e.g. the airport and nearby Tunel Spasa, (see #Get in ), Sarajevo East bus station or Vratnik district east of the centre, Buses 51, 52 or 55.

Bus tickets are always bought at the driver for 1.40 KM. You can not use pre-bought tram tickets in buses.

The planned departures of buses and trams can be found in the Moovit app ( iOS , Android ).

At first sight only for committed urban cyclists: Sarajevo traffic can be as hostile to cyclists as it is to fellow-motorists, only with worse results. However, there are in fact separate cycle lanes along the river and/or the main west-east boulevard for more than 5 km, with the easternmost point being the parliament area / Muzeji tram stop.

Nextbike has a bike rental scheme here and in Tuzla. First you need to register and pay a 20 km deposit, easiest done online. It may take 24 hours to activate but if you're already registered with them in another country, you should be good to go. There are 14 pick-up / docking stations all along the tram lines out to Dobrinja near the airport, their map shows real-time availability. The first 30 mins per day are free, a further 30 mins cost 1.50 KM.

Taxi scams are common especially at the main train & bus stations and the airport. Try to avoid using taxis when possible, as even supposedly legitimate operators can scam. Know roughly what the honest fare should be, and insist on them using the meter. All legitimate taxis have a "TAXI" sign on top, licence plates with "TA", and have a meter. Flagfall is 1.90 KM then it's 1.20 KM per km, plus maybe 1 km for luggage, so a trip between Baščaršija and airport shouldn't exceed 20 KM. Pay in cash, the driver will issue a receipt upon request. Some official operators are

- Paja Taxi 1522 or ☏ +387 33 15 22

- Žuti (Yellow) Taxi ☏ +387 33 66 35 55

- Samir & Emir Taxi 1516

- Holand Taxi tollfree 0800 2023

The best way to find a reputable taxi is to ask a local person you trust which one they would use. Ownership and management of official operators can change frequently.

By shared electric scooter

Renting an electric scooter is available in Sarajevo like in many other European cities. You can use the app BeeBee to access them.

With the exception of the Tunnel Museum and the Bosna spring, all landmarks are in or within walking distance of Old Town. Several walking tours are available, a free/tip based walking tour starts every day at 10:30 at the crossing of Gazi Husrev begova street and Mula Mustafa Baseskija street (address: Velika Avlija 14) and covers most of the Baščaršija.

The municipality of Sarajevo provides an app called "Guide2Sarajevo" (Android, ios). It contains a map with sights and restaurants as well as several themed routes to walk in the city (ranging from 2 to 6 hours) on which you use your phone as audio guide (works even without mobile internet, because the files are downloaded on installation). It's remarkably well made.

Baščaršija is the historic district of Sarajevo. The cobbled streets, mosques and oriental-style shops at the heart the city feel like a world away from Europe when the call to prayer starts. You could be walking by a Catholic church, Orthodox church or a synagogue and hear the Islamic call to prayer at the same time. In this old bazaar you can find dozens of shops selling copperware, woodwork and sweets. Many historic monuments are situated around Gazi Husrev-begova street.

Sarajevo has numerous museums on a variety of topics. The museums can offer an air-conditioned refuge from heat during Sarajevo's hot summers, or a place to warm up in the chilly winter months.

History and archeology

War memorials.

Scars from the Bosnian War can still be seen in many parts of the city, as bullet holes in walls or abandoned buildings. The unresolved conflict (see box The Yugoslav Wars ) left traumatic memories, and museums and memorials associated with the Bosnian War are scattered around the city.

- Sarajevo Roses are scars left in the concrete from mortar blasts during the Siege of Sarajevo, filled with red resin. Around 200 can be found throughout the city.

- ICAR Canned beef monument In the vicinity of the National Museum and the Bosnian Historical museum. A giant can of beef meant as a sarcastic sneer at inadequate help from the European community during the siege. The infamous canned beef was inedible, and according to popular legend even refused by stray cats and dogs. The city was also supplied with 20 years out-of-date rations from the Vietnam war, and pork for a muslim-majority population.

- Cemeteries: those who died in the 1990s war were buried in pre-existing cemeteries. In these you find old Ottoman turbe , Austro-Hungarian dignitaries, casualties of two World Wars, Yugoslav citizens - and then row upon row upon aching row of simple white marble stones for people in their twenties slain in the latest conflict.

- The grandiose Academy on the south bank facing Festina Lente bridge was originally a church, built in 1899 to Karl Pařík's design. It's now the Academy of Performing Arts within the University of Sarajevo, but no longer fit for purpose and they plan to move elsewhere. So just admire the facade.

Administrative buildings

Religious buildings

- The Franciscan Monastery ( Franjevački samostan na Bistriku ) next to the church was built in 1894, also in Gothic Revival style and designed by Karel Pařík. It's still a monastery and therefore seldom open to visitors, but its collection of paintings, sculptures, organ, manuscripts and books are occasionally put on view.

The Jewish population was first established in 1492-97 when Sephardic Jews fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, and settled here and in other Ottoman cities. The Ashkenazi Jews mostly arrived during Austro-Hungarian rule in the late 19th century. Inter-community relations were mostly amicable and the population was relatively unharmed by the First World War, collapse of Austria-Hungary and formation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. By 1940, their numbers peaked at around 14,000, 20% of the city population. In 1941 the Nazis invaded, placing the country under the control of the Croatian Ustaše , who vigorously set about the deportation and extermination of minority groups. Those who could, fled to the west, and after the war most exiles remained abroad. Some 2000 Jews did remain or return, but when the 1990s civil wars broke out, there was a mass evacuation to Israel of Jews living in former Yugoslavia. Fewer than 1000 remain in Bosnia and Herzegovina today, perhaps half of them in Sarajevo.

Ottoman bridges

During Ottoman rule of Sarajevo, 13 bridges were built over the Miljacka River and Bosna River. Four stone bridges remain: the Latin Bridge , the Šeher-Čehajina Bridge , the Goat Bridge and the Roman Bridge .

Goat's Bridge

The bridge had an important ceremonial function, as it served as the place where each Ottoman vizier was welcomed by the previous vizier and citizens of Sarajevo. The bridge is constructed from white marble, has a single arc with two circular apertures, and is 42 m long and 4.75 m wide. The span of the main arc is 17.5 m. According to the legend, before the bridge's existence, a poor shepherd noticed his goats sniffing on a shrub along the Miljacka River. Upon inspecting the shrub, he found a treasure with golden coins, which he used to finance his own education. After he became wealthy and influential, he had the bridge constructed at the shrub where his goats found the treasure, which gave the bridge its name. The truth in the legend was lost in history, but the bridge was almost certainly built between 1565 and 1579, a time when the road network underwent major infrastructure upgrades under reign of Mehmed-paša Sokolović.

If you came to the bridge on the cycle/pedestrian path along the river by foot, you can continue the road after the goat bridge uphill to Vakuf Isa-bega Ishakovića (a view point) and then few hundred meters further on the cycle path to Pale turn right to Jarčedoli . Once you reached the 43.85409 18.44804 51 top of the hill , you'll have majestic views over Sarajevo, especially the hills and ruins on the opposite site.

From there follow many stairs and narrow streets down to Alifakovac which ends at the city hall.

In the 17th century conflict between Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, the decisive battle came at Zenta (now in Serbia) in 1697, when the Ottomans were routed, and their grip on central Europe was broken. The Austro-Hungarian forces then devastated Sarajevo before marching home. Further attacks were likely so a fortified city was built here 1727–1739, east of the old centre of Baščaršija. Later suburbs surrounded it, and the name Vratnik (probably meaning "gates") applies to this wider district, but the sights of interest are all in the Vratnik redoubt.

From Baščaršija either walk up Kovači past the war cemetery onto Jekovac and Carina (Buses 51, 52 & 55 run this way); or follow the river upstream taking the right fork just before the road goes into a tunnel, then ascend right for White Fortress or left for Yellow Fortress.

- Jajce Kasarna are Austro-Hungarian barracks 200 m east of Yellow Fortress. They're derelict and unsafe to enter.

Sarajevo hosted the 1984 Winter Olympic Games . These (officially the XIV Olympic Winter Games) were the first held in a socialist state, although Moscow had hosted the 1980 Summer Olympics. Some structures remaining from that era are in a sorry state.

- Cable car ( From Franjevačka south of the river, a short walk over the river from the City Hall. ). M-Tu 10:00-20:00; W-Su 09:00-20:00 . Restored in 2018, this cable car runs up to the former 43.83979 18.44876 59 Ski Station –Though, a little oberpriced. Nice views hilltop strolls and a decent cafè. Forest paths lead to the Pino Hotel (accessible by road, e.g. drive or taxi) and the pictureque and Instagram-heavy Trebevic Bobsled Track which mad off-road bikers hurtle down, and which is being restored for winter sports. It makes sense walking one direction to see the bobsled track, and using the cable car the other direction, since the slide is pretty much between the Ski Station and city. 30 KM return, 20 KM one-way (locals pay less than a third) . ( updated Sep 2024 )

- Fox in a Box , Sime Milutinovica 15/I ( Next to Museum of Literature & Performing Arts, off Zelenhi berekti ), ☏ +38 761 10 10 07 , [email protected] . 09:30-22:30 . Escape room games. In "Mr Fox's Secret Study", you try to escape from the office by solving riddles. In "The Bank Job", you try to steal diamonds from the bank safe, in the dark by torch. In "The Bunker", you try to avert an accidental nuclear war. 60 KM . ( updated Jul 2019 )

Recreation parks

- Sarajevo City Centre mall has a large play area for children. BBI Centar a smaller one. Both malls are slightly west of the city centre on the main road.

- 43.82769 18.311064 9 Ilidza Thermal Riviera ( Termalna rivijera Ilidža ), Butmirska Cesta 18, 71211 Ilidza ( behind the airport, 5 minutes walk from Ilidza tram station ), ☏ +387 33 771-000 . 09:00-22:00 . Water park with several indoor and outdoor swimming pools, wave pool, massage amenities and water slides. Slightly outdated infrastructure, but the natural sulphur rich water makes up for it on hot summer days. Sauna and fitness centre available at the adjacent Hotel Hills. Basic entry 9 KM, extra for wellness & fitness centres . ( updated Mar 2018 )

- From May to August there are white-water rafting trips down the river Neretva. The usual base for trips is Konjic midway between Sarajevo and Mostar. Operators who do package day-trips from Sarajevo include Sarajevo Funky Tours , Sarajevo Insider , Meet Bosnia Travel and Balkland . These cost about 100 KM including transport and lunch.

- See Sarajevo Region for the ski resorts of Jahorina, Bjelašnica and Igman, all about 35 km away.

Sonar compiles the city's regular calendar of events.

- Nights of Baščaršija: throughout July the old town centre has theatre performances, classic and rock music concerts and folklore dances. Various locations but concentrated around Ćemaluša.

Most shopping centres and upscale restaurants accept credit cards. Small cafés, clubs and souvenir shops mostly require cash, but might jib at notes larger than 20 KM.

- 43.86712 18.41071 2 Pijaca "Ciglane" . Interesting local market where you won't find any tourist. ( updated Mar 2023 )

In addition to the usual types of souvenirs, such as key rings, are more distinctive carpets and copperware, not all of which are locally made. Over a century ago, each street in this area hawked a specific ware: for example, one street had all the coppersmiths, shoes were on another, jewellery on another. An underground souk (open 08:00-20:00) stretches along the west side of Gazi Husrev-begova street. Prices are generally fixed, and so whilst haggling for a 4 KM keyring is pointless it may be possible for bulk purchases or the odd 2,000 USD carpet.

- Isfahan Gallery , Saraći 77 ( inside Morića Inn ), ☏ +387 33 237 429 , [email protected] . Persian carpet seller inside the Morića Inn. The handcrafted carpets are pricey, but the setting inside the reconstructed inn is worth a visit. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.858564 18.418458 4 Sahinpasic , 38d Titova , ☏ +387 33 220-112 . Has a decent collection of historical literature.

- 43.85894 18.43061 5 Baklava Shop Sarajevo , Ćurčiluk Veliki 56 ( on the northern side of Brusa Bezistan ), ☏ +387 61 267 428 . A wide selection of baklava in many flavours (walnut, almond, hazelnut, pistachio, etc.), where the baklavas containing orah (walnut) are considered to be the most traditional ones. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.85923 18.43151 6 Kazandžiluk Street . The street is named after Sarajevo’s master coppersmiths, featuring shops such as Sakib Baščaušević and Aganovic. ( updated Sep 2017 )

Shopping malls

Sarajevo offers numerous shopping malls, the most notable being the Sarajevo City Center in the commercial district. Most shopping malls in Sarajevo have been newly constructed or renovated, and offer a modern shopping experience to those who can stand the annoying pop music they play all day long.

- 43.85641 18.40593 8 Alta Shopping Center , Franca Lehara 2 ( across the street from the Sarajevo City Center ), ☏ +387 33 953-800 . M-Sa 09:00-22:00, Su 10:00-20:00 . Shopping centre in the commercial district of the city, with 70 stores. Famous for the Lego store inside. ( updated Aug 2017 )

- 43.85831 18.41663 9 BBI Center , Trg djece Sarajeva 1 ( across the street from Veliki Park ), ☏ +387 33 569-990 . M-Sa 08:00-22:00, Su 08:00-22:00 . Second largest shopping centre in Sarajevo, after the City Center with 125 stores. It won the ICSC European Shopping Centre Awards in 2011. ( updated Aug 2017 )

- 43.847 18.37427 10 Bosmal City Center , Milana Preloga 12A , ☏ +387 33 725-180 . Shopping centre on the south bank of the river with 50 stores. ( updated Aug 2017 )

- 43.8549 18.3998 11 Importanne Center , Zmaja od Bosne 7 , ☏ +387 33 266-295 . 07:00-23:00 . Smaller shopping mall with around 35 stores. ( updated Aug 2017 )

- 43.8572 18.3843 12 Mercator , Ložionička 16 . One of the oldest shopping malls in Sarajevo with around 35 stores. ( updated Aug 2017 )

- Grand Centar Ilidža , Butmirska cesta 14 , ☏ +387 33 629020 . M-Sa 08:00-22:00; Su 08:00-21:00 . Ilidža shopping centre with 33 stores is by the #3 tram terminus and Thermal Spa. ( updated Aug 2017 )

The local currency is konvertibilna marka (KM, Convertible Mark , international abbreviation BAM), fixed at €1 = 1.95583 KM (~1 KM = €0.51)), and is used throughout the country. Informally, restaurants may accept euros at €1 = 2 KM. The odd rate is because the Convertible Mark was originally pegged 1:1 against the Deutsche Mark, which was replaced with the euro at that rate.

There are many banks along Maršala Tita at the north boundary of Old Town, usually open M-F 08:00-18:00, Sa 09:00-13:00. Money can also be exchanged at any post office or at currency exchange booths, which stay open till 21:00: as always take care to check both the exchange rate and level of commission.

It is said in Bosnia that some people eat to be able to drink, others eat to be able to live and work, but true Bosnians work and live to eat. A lot of attention is devoted to the preparation and consumption of food in Sarajevo. Gastronomy in the city was developed under Eastern and Western influences, and Bosnian cuisine focuses on local produce like meat, vegetables, fruits and dairy products. For information on typical Bosnian foods, see Bosnia#Eat .

Cheap food on the go, from a myriad small shops and cafés, is burek , ćevapi or pita . Burek is meat pie. Ćevapi are grilled meats; the word derives from "kebab" and the traditional Sarajevo style is minced beef and mutton in a somun flatbread. Pita is a filo pasty or pie, typical varieties being meat ( meso ), cheese ( sirnica , similar to ricotta), cheese and spinach ( zeljanica ), pumpkin ( tikvenica ) and spicy potato ( krompirusa ).

City centre around the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

- 43.859022 18.431635 1 Buregdžinica Bosna , Bravadžiluk 11 , ☏ +387 33 538-426 . Daily 08:00-23:00 . Pita & burek café, sandwiched between Mrkva and Bosnian House. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.8589 18.429663 2 Fan Ferhatović , Čizmedžiluk 1 . Pleasant ambience in the bazaar, good local food, friendly staff. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.85876 18.429662 3 Ćevabdžinica Željo 3 , Ćurčiluk veliki 34 . Traditional Bosnian barbecue food. The atmosphere is great. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.858863 18.431381 4 Sač , Bravadžiluk mali 2 . Authentic Bosnian cuisine with yummy burek and excellent pies. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.85872 18.42564 5 Teraza , Strossmayerova 8 , ☏ +387 61 569 513 . Pizzas and Bosnian sandwiches. Excellent location just heart of the city center with unique retro design makes you feel calm and relax. The food and the service are good. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.859124 18.426409 6 The Epicentrum , Muvekita 11 . Excellent homemade food, paradise tomato soup. ( updated May 2022 )

City centre around the Vječna vatra memorial

- 43.859822 18.425833 7 Pizzeria Ago , Mula Mustafe Baseskije 17 , ☏ +387 33 203-900 . 08:00-23:00 . Good value pizzas, and pancakes at only 2 KM. Excellent pizzeria, great service and staff. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.858808 18.423346 8 Srebrena školjka , Ferhadija 7 . Traditional Bosnian cuisine in a fabulous atmosphere, very very nice staff, almost like stepping back in time. If you're looking for a break from the hustle and bustle of the summer heat, this is it. The upstairs dining room has character and a great view down into the market. The owners are warm and friendly. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.858412 18.423304 9 Ćevabdžinica Nune , Ferhadija 12 . A little restaurant in the backyard of the main street Ferhadija. Super cute father and son shop with some of the best cevapci in town! Definitely a recommendation for a quick meal. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.85928 18.425207 10 Chipas , Trg Fra Grge Martića 4 . Excellent food, fast service, very cultured and friendly waiters, everything clean and tidy. A large selection of food and drinks at a very decent price. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.858996 18.425629 11 Sedef , 71000 Ferhadija 16 BA . Traditional dishes, comfortable and quiet place in an alley. A very beautiful restaurant, the food is delicious and clean, and the service is amazing. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.8596 18.42188 12 Cakum-Pakum , Kaptol 10 , ☏ +387 61 955 310 . A little restaurant with great crepes. There is kind of a hype about this place. It's nice and cozy and has a wonderful interior design. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.84886 18.38417 13 Pizzeria Maslina , Trg Heroja 12 , ☏ +387 62 751 200 . Affordable with a diversity of cuisines, from Italian to Bosnian traditional food. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.859016 18.432226 14 Petica Ferhatović , Bravadžiluk 21 , ☏ +387 33 537 555 . Daily 08:00–23:00 . Popular but spacious serving fresh beef ćevapi. The waitresses wear traditional Bosnian dresses. 6 KM for ćevapi (July 2019) . ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.858548 18.428448 15 Ascinica ASDž , Ćurčiluk mali 3 in Bascarsija , ☏ +387 33 238-500 . 08:00–19:00 . When you get sick of greasy meats, ASDž serves Bosnian-home-cooking, vegetable-based dishes (but don't expect vegetarian, as many are still flavoured with little meat). Order cafeteria-style at the counter: you pay by the plate, and can mix-and-match different foods onto the same plate. ( updated May 2022 )

- 43.852949 18.40026 16 Cappuccino , Grbavica ( near river Miljacka in green area ). Daily 07:00-22:00 . Delicious Bosnian meals and the best pasta and pizza in the region. Good for a full meal, a snack or just a coffee. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.85973 18.4281 18 A P Ǝ T I T , Gazi Husrev begova 61 , ☏ +387 62 86 81 31 , [email protected] . An "open kitchen" and a daily menu prepared from ingredients; meat dishes, fish dishes, risottos, pastas, imaginative salads, fragrant woks and delicious sweet pleasures. Also dishes for vegans, vegetarians and gluten-free offerings. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.859598 18.43048 19 Dveri , Prote Bakovića 12 , ☏ +387 33 537-020 , [email protected] . 09:00-23:00 . Homestyle restaurant in heart of old Sarajevo. Very cozy feel, with strands of garlic, lots of delicious warm bread, hearty soups, meats, etc. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.861024 18.417922 20 Mala Kuhinja , Tina Ujevića 13 , ☏ +387 61 144 741 , [email protected] . M-Sa 10:00-23:00 . Tiny restaurant, only seats 15, owned by Bosnian celebrity chef Muamer Kurtagic. No menu: he prepares what is fresh each day and for any preferences. You watch the work in progress. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.87152 18.42758 21 Restaurant Kibe , Vrbanjuša 164 , ☏ +387 33 441 936 , +387 61 040 000 (Mobile) , [email protected] . With stunning panoramic views of the city, Kibe Mahala offers a selection of national dishes, such as spit-roasted lamb, and a wide assortment of wines from Bosnia and Herzegovina and the region. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.830013 18.303705 22 Restoran Brajlovic , Samira Ćatovića Kobre 6, Ilidža , ☏ +387 33 626-226 . 07:00-23:00 . At the water front of the Zeljeznica, offers an up scale selection of Bosnian specialities. Their cevapcici is popular. ( updated Aug 2022 )

- 43.856868 18.432245 23 Sarajevo Brewery ( Sarajevska pivara ), Franjevačka 15 , ☏ +387 33 491-100 . Daily 10:00-01:00 . A large bar and restaurant near the Latin Bridge. Serves 'western' food, only so-so quality & amount for the price, plus a variety of beers brewed on the premises. Sometimes smoky & lacking ventilation, quality of service variable. The brewery also has a souvenir shop / museum. ( updated Aug 2022 )

Sarajevo has vibrant night life with a plenty small thematic bars. Clubs are usually opened until early morning. Thursday, Friday and Saturday are hot days to hang out despite the rest of the week offers quite good night life. There are probably over 100 cafés in the city, centred in the old town, but a clear distinction is made whether the traditional Bosnian coffee is served or not.

- 43.85914 18.43174 1 Bosanska kafana "Index" , Bascarsija 12 ( Kazandziluk ), ☏ +387 33 447-485 . Bosnian coffee ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.84906 18.38555 2 Cafe Slastičarna "Palma" , Porodice Ribar br.5 , ☏ +387 33 714 700 , [email protected] . Coffee and pastry shop, located in the part of town called Hrasno, started in 1970. In 1985 "Palma" received the CD -Diplomatic Consular Code. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.86036 18.4322 3 Ministry of Ćejf , Kovači 26 , ☏ +387 61 482 036 . Great espresso and well trained baristas. Also has karak and good cakes. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.85911 18.42955 4 Miris Dunja , Ulica Čizmedžiluk 9 , ☏ +387 62 922 900 . Coffee, including Bosnian coffee, and fruit juices. On a typical day the Bosnian coffee is very good, and on a good day it is extraordinary. Bosnian coffee: 2 KM . ( updated Aug 2019 )

- 43.85351 18.37176 5 Mrvica , Paromlinska 58h ( located in the Novo Sarajevo residential area, near "Vjetrenjača" (Windmill) ), ☏ + 387 62 887 777 , [email protected] . Coffee, brunch or even lunch ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.85929 18.42609 6 Mrvica Old Town , Ulica Jelića 5 ( near the Sacred Heart Cathedral "Katedrala Srca Isusova" ). Coffee and different types of cakes and desserts. No Bosnian coffee served, only "modern" coffee styles. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.857629 18.421401 7 Opera Bar/Café , B Sarajeva 25 ( opposite the city's Opera house ), ☏ +387 33 831-647 . 07:00-12:00 . Fast WiFi connection, but the staff can be unfriendly and inattentive. Attracts the acting and musical community among the regulars, though this isn't an exclusive kind of place. A bit smoky. Espresso: 2 KM . ( updated Jul 2017 )

- 43.856407 18.426087 8 Café de Paris , Hamdije Kreševljakovića 61 ( South end of Ćumurija bridge, in the green-and-yellow building. ), ☏ +387 33 211-609 . 07:00–22:00 . You might not have expected to find an IPA in the Balkans, but Café de Paris serves a selection of craft beers from Sarajevo microbreweries. They also have a range of very smooth local rakijas (try the quince). Riverside, outdoor seating looks out upon impressive architecture from the Austro-Hungarian times. Craft beer 3–4 KM . ( updated Oct 2016 )

- 43.855161 18.421549 9 Tre Bicchieri Wine Store & Tasting Bar , Cobanija 3 , ☏ +387 33 223-230 . Long list of Italian wines. Very cozy and comfortable place. Good music & relaxing atmosphere. ( updated Jul 2017 )

You need to register with the local police within 24 hours of arrival. Your hotel or hostel should do this on check-in, but if you wild-camp or stay at a private residence, you need to organise this yourself. Failure to register doesn't normally bother the authorities but could result in a fine or deportation.

- You can wild camp in the park by the River Miljacka. Chances are you'll see tents already there. Follow the road west and stay close to the river. In summer there is a public toilet. No guard or services.

- Locals may unofficially let you stay in their property, payment to be negotiated.

- 43.862102 18.439061 1 Haris Youth Hostel , Vratnik Mejdan 29 , ☏ +387 33 23 25 63 . Haris is the owner, friendly fellow who also owns a tourism agency near the pigeon square at Kovaci 1 and can take you on tours around the city, annotated with his own experiences from the war. The hostel is ten minutes uphill walk from the main square, worth it for the view and hospitality. Dorm 18 KM ppn, private rooms 40 KM ppn . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.858481 18.426597 2 Hostel City Centre Sarajevo , Saliha Hadzihuseinovica Muvekita No. 2/3 ( Between Ferhadija and Zelenih beretki streets ), ☏ +387 61 757 587 . Check-out: 10:00 . Clean and tidy place to stay with kitchen facilities, 2 large living and common rooms, cable TV, free internet and wifi. They have 4- ,5- ,6- and 10-bed mixed dorms plus 2,3 and 4 bed private rooms. You'll need to lug your baggage up 4 flights, no lift. Dorm 30 KM ppn . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.847502 18.391441 3 Motel Jasmin , Kupreska 26 ( Bascarsija ), ☏ +387 33 71 61 55 . Singles, doubles, triples with separate bathrooms and TV. Cleanliness very variable. B&B double 60 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.860196 18.431075 4 Hostel Ljubičica , Mula Mustafe Bašeskije 65 ( Old Town, tram stop Bascarsija ), ☏ +387 61 131 813 . The hostel itself is friendly, central for Old Town and usually clean. However it's also a travel & accommodation agency, and may place you in any of a number of dorms in the area; it may not be clear at the time of booking what you're getting. Dorm 30 KM ppn . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.85871 18.429286 5 Hostel Kod Keme ( Kemal's Place ), Mali Ćurčiluk 15 ( Bascarsija ), ☏ +387 33 531-140 . Small friendly guesthouse with private rooms, no dorm. B&B double 80 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.858677 18.431736 6 Pansion Sebilj , Bravadžiluk bb ( Obala Kulina baba between Careve cuprija and Novi most at the Miljacka riverside ), ☏ +387 33 573-500 . Most of the staff speak English fluently. An internet-cafe is downstairs in the same house, a restaurant in the atrium. The restaurants in the Old Town, groceries and a pharmacy are all in walking distance. Good location, friendly staff, hot water, clean. But no internet, walls are paper thin, you can hear everything in the next room, and the downstairs bar plays loud music till midnight, uncomfortable slat beds. Unisex showers (only 2) and bathroom. No way to lock bathroom or shower area when inside. No laundry service, no kitchen. No lockers for gear. 30 KM ppn . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.8646 18.436327 7 Hostel Tower , Hadzisabanovica 15 , ☏ +387 61 800 263 , toll-free: +387 61 566 350 , [email protected] . Clean & mostly friendly place, wifi weak. On two occasions in 2018-19, guests fell foul of the owner and were literally kicked out, with a boot to backside. Dorm 20 KM ppn, private room from 40 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.861762 18.432935 8 Hotel Hayat , Abdesthana 27 ( a less-than 5-minute walk northeast from the Kovači Square, near Bascarsija ), ☏ +387 33 570-370 . 130 KM . ( updated Jul 2017 )

- 43.865076 18.405322 9 Hotel & Hostel Kan Sarajevo , Brace Begic 35 ( near the bus station ), ☏ +387 33 220 531 . Single to quadruple bed- bedrooms as well as apartments. Restaurant on site and personal assistance with sightseeing. From 40 KM. ( updated Jul 2017 )

- 43.859972 18.429767 10 Garni Hotel Konak , Mula Mustafe Başeskije 54 ( Tram 1 to Pigeon Square, follow tram tracks west for two blocks, look left for the red and white sign ), ☏ +387 33 476 900 , [email protected] . Staff are friendly, speak English, and in the off season can be persuaded to negotiate. Hotel amenities include breakfast, ensuite bathrooms and internet connected computers, while the hostel rooms are double bed privates with satellite television which share a bathroom among three rooms. B&B double from 140 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- Hotel Hecco Deluxe , Ferhadija 2 ( By Eternal Flame ), ☏ +387 33 558 995 , [email protected] . Business hotel with suites and terrace restaurant. It's on the top floors of a building that is otherwise empty, so it's a bit spooky in hours of darkness. Often smells of cigarette smoke. B&B double 140 KM . ( updated Jul 2019 )

- 43.86159 18.422495 11 Hotel Michele , Ivana Cankara 27 , ☏ +387 33 560 310 , +387 61 338 177 , [email protected] . In a quiet area. The staff are nice, breakfast and laundry included plus private parking with direct elevator access to the room floors. B&B double 120 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.860237 18.426884 12 Hotel VIP , Jaroslava Černija br 3 , ☏ +387 33 535533 , [email protected] . Latin bridge is 300 metres from Hotel VIP, while Bascarsija Street is 300 metres away. The airport is 9 km. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.859909 18.426867 13 Motel Sokak , Mula Mustafe Bašeskije 24 ( Just down the road from the Bascarsija tram stop. ), ☏ +387 33 570-355 , [email protected] . It's small clean, quiet, friendly and comfortable, in an old building but modern inside. Double: 185 KM . ( updated Jul 2017 )

- 43.857876 18.427334 14 Opal Home Sarajevo ( Hotel Opal Home ), Despićeva 4 , ☏ +387 37 445 445 , [email protected] . The four-star hotel with modern design and luxury interior. 12 comfortable rooms and 22 beds. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.86081 18.43111 15 Pansion Stari Grad , Sagrdžije 29A ( walk up the hill from the Sebilj ), ☏ +387 33 239 898 , [email protected] . Check-out: 10:00-11:00 . A cozy hotel walking distance from the old town with friendly staff willing to help guests get around the city with maps and tips. Double 100 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.828937 18.358975 16 Hotel Terex , Ive Andrica 23, 71123 Dobrinja ( on a walking distance from the airport ), ☏ +387 57 318 100 , fax : +387 57 317 150 , [email protected] . Small hotel surrounded by apartments in the residential area of Dobrinja, close to the Dobrinja commercial district. 180 KM . ( updated Oct 2017 )

- 43.833145 18.348289 17 Hotel Imzit , Lukavička Cesta , ☏ +387 33 451 423 , [email protected] . Basic hotel at the outskirts of Dobrinja at the foot of Suma Mojmilo hill. 160 KM . ( updated Oct 2017 )

- 43.82807 18.339722 18 Hotel Octagon , Akifa Šeremeta 48 , ☏ +387 33 789-905 . A lovely 3 star hotel in a residential area across from the airport, ideally suited for business travellers on a lay-over. 160 KM . ( updated Oct 2017 )

- 43.856425 18.403564 19 Hotel Holiday ( formerly Holiday Inn ), Zmaja od Bosne 4, 71000 Sarajevo ( 5 min walk from train and bus station ), ☏ +387 33 288 200 , +387 33 288 300 , fax : +387 33 288 288 , [email protected] . Check-in: 12:00 , check-out: 12:00 . Clean, safe, nice private rooms with private bathroom and shower, well-maintained. Friendly staff speak English. Credit cards accepted. The restaurant on the third floor is great. 236 KM . ( updated Aug 2018 )

- 43.852839 18.38968 20 Novotel Sarajevo Bristol , Fra Filipa Lastrića 2 ( Tram stop Pofalići ), ☏ +387 33 705 000 , [email protected] . Check-in: 14:00 , check-out: 12:00 . Business hotel now part of Accor chain. Great rooms and comfortable beds. Friendly staff, three restaurants/cafés. Halal certified. Held in regard as one of the best large hotels in the city. Entrance fee to a small spa is included in the room price. B&B double from 180 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.857929 18.425978 21 Hotel Central , Ćumurija 8 ( facing Strossmayerova pedestrian mall ), ☏ +387 33 561 800 , [email protected] . Clean comfy hotel, and it is indeed central. With spa and fitness centre. B&B double 220 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.860374 18.41438 22 Hotel Colors Inn ( Colors Inn Sarajevo ), Koševo 8 , ☏ +387 33 276600 , [email protected] . Has 37 single and double rooms and a private parking. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.85817 18.43015 24 Hotel President Sarajevo , Bazardžani 1 , ☏ +387 33 575 000 , [email protected] . Located near the centre of the old town of Sarajevo. Hotel President offers 72 comfortable rooms, garage, breakfast room, Congress Hall as well as a Café/lobby bar. ( updated Sep 2017 )

- 43.843606 18.335791 25 Radon Plaza , Džemala Bijedića 185 ( foot of Avaz tower, next to BMW showroom ), ☏ +387 33 752 900 , [email protected] . Swish hotel, named after its owner, who is also the owner of Avaz newspaper and one of the city's wealthiest people. B&B double 200 KM . ( updated Jun 2019 )

- 43.827716 18.36586 26 Hotel Espana , Ive Andrića bb, 71123 Lukavica ( on a walking distance from the airport ), ☏ +387 57 961-200 , fax : +387 57 961 202 . Hotel in a calmer residential area of Sarajevo on the territory of Republika Srpska . 220 KM . ( updated Oct 2017 )

There are four mobile operators in Sarajevo: BH Telecom (060, 061, 062), m:tel (065, 066, 067), HT Eronet (063) and Haloo (064). Since Bosnia and Herzegovina is not part of the EU or EEA, the international roaming charges are not capped as those have been since 2017, and can be much higher. However Bosnia and Herzegovina is part of a Balkan roaming zone with Montenegro, Serbia and North Macedonia, capped at €0.20 per MB from July 2017. But that only applies if you have a local SIM card, from any of the operators, which can be purchased in one of the many kiosks around the city. BH Telecom, m:tel and HT Eronet have offers aimed towards tourists, starting from 20 km for 5 GB.

The local area code is +387 33 ( Kanton Sarajevo ) and the local postal code is 71000.

- BH Telecom , Sarači 60 , ☏ +387 33 238-573 . M-F 08:00-22:00, Sa 08:00-16:00 . Several locations, the most convenient for Old Town is on Sarači next to the TIC. Basic mobile internet package for 5 KM (300 MB) and "Ultra Tourist 1" for 20 KM (5 GB). Ask for BH Mobile's Tourist SIM. ( updated Jul 2019 )

- Central Post Office BH Pošta is a sight in itself, see "Administrative buildings" listing earlier. It's at Obala Kulina bana 8 next to the National Theatre.

- There's another big post office next to the railway station, open M-F 07:30-18:00 and Sat 08:00-16:00.

There are still many minefields and unexploded ordnances in the broader Sarajevo area (although not in any urban area). Never go into damaged buildings (which are really rarely seen) and always stick to paved surfaces avoiding grassy hills that surround the city. As of 2020, Trebević has been completely demined. Areas that are not cleared are marked by yellow tape or signs, but still not all minefields have been identified due to the lack of resources and the lack of international help. Paved roads are always safe. Crime against foreigners is very rare and the city is safe to visit. (As with any country in former Yugoslavia, be careful not to get into sensitive discussions about politics with people you do not know, but even those can be very educational when you come across a person who's willing to discuss it.) Be aware of pick pockets who usually operate on public transportation.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has double the traffic fatality rate in Europe as a whole, and in the early 2020s there have been a few high-profile accidents with pedestrians. Be alert whether driving or crossing the street.

There are an incredible number of pickpockets working in the city and very few police officers on patrol; police are rarely seen. Pickpockets are very sloppy and it's pretty easy to spot them, but with that number of people picking the pockets they probably will succeed eventually.

Due to being surrounded by hills the air in Sarajevo in winter months (November-February) can be noticeably thick with pollution, so that asthmatics or those with other chest problems may find themselves short of breath a lot of the time, particularly at night. Ensure you have ample medication, just in case.

Avoid areas of the city such as Alipašino Polje, Švrakino and the surrounding areas of the Novi Grad municipality as those are mainly dangerous zones with high crime rates, shootings, violence and poverty. Go there only with locals and not during the night. Anyway it is off the tourist trail and you most likely won't have any reason to even go to those parts. Getting there accidentally is next to impossible as these rough neighbourhoods are far from the city centre and any of the sights in outlying areas.

Emergency services

- General emergency number , ☏ 112 .

- Police , ☏ 122 .

- Fire , ☏ 123 .

- Ambulance , ☏ 124 .

- Mountain Rescue , ☏ +387 33 61 29 94 43 , toll-free: 121 .

- BIHAMK ( Road Assistance ), ☏ 1282 .

Stay healthy

- Water from fountains and taps in Sarajevo is safe to drink, but it may have an unpleasant chlorine odour. The mains supply may be turned off overnight.

- The main risk to your health, land mines aside, is the strong sunlight. Usual precautions: hat, long-sleeved shirt, seek the shade and apply sun screen.

- Pharmacies ( Apotheka ) are dotted around the city. Two handy for Old Town are Al-Hana on Ulika Patka, and Apoteka Baščaršija at Obala Kulina bana 40 by the riverside.

- 43.85864 18.40809 3 General Hospital ( Dr Abdulah Nakaš Hospital ), Kranjčevićeva 12 , ☏ +387 33 285-100 , [email protected] . Only if it's serious. ( updated Jul 2019 )

- Poliklinika Dr Al-Tawil inside the Importanne Centar shopping mall (see the Buy section ). Modern facilities and relatively short waiting time. Some blood tests within half an hour.

Cultural heritage from the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and most recently Yugoslav periods has been assimilated into modern Sarajevo as a multicultural, multireligious metropole. Catholic and Orthodox Christians and Muslims share the city, and as such, common sense regarding respect towards people of these religious backgrounds should be upheld. Even the younger generation is on average very religious in comparison to other European capitals, although not all religious traditions may be followed equally strictly. For example, young Muslims may choose to drink wine but refuse pork, while older Muslims likely abstain from both. Keep this in mind when offering presents to your host family. When visiting mosques, skin-covering clothing should be worn, and women should wear a scarf covering their hair. At the most touristic mosques, scarfs are available for visitors to borrow.

Although the Bosnian War ended with a UN enforced cease fire, the underlying conflicts between the different ethnic groups in Sarajevo are far from resolved. Many inhabitants have survived the siege of the city from 1992–95, and almost everyone has lost relatives and/or friends in the conflict. Strong anti-Serb sentiments may be present among the Bosniak population, and scars from the war are left in memory. While the war is not a taboo subject, as evidenced by the many memorials and museums scattered around the city, it remains a sensitive topic that easily brings up negative memories, if addressed uncomprehendingly. Aside from anti-Serb sentiments, many also feel dismay or anger towards the United Nations, which are blamed for the Srebrenica massacre and inadequate protection of Sarajevo citizens during the Siege.

There is an ongoing dispute between Bosnian unionists and Serb separatists, striving for the independence of Republika Srpska . Since the neighbouring town of East Sarajevo is on the territory of Republika Srpska, opinions will vary depending on where you ask in the city, although the relations are less tense than in other parts of the country and people don't have issues crossing the geographical borders. The political situation in Sarajevo in particular is complex, and outsiders taking a position may be accused of uninformed interference in internal Bosnian affairs. In general, it is advised to abstain from discussing politics, unless your conversation partner brings up the topic him/herself and asks for your opinion.

- Konjic – 43 km southwest of Sarajevo, has Tito's enormous bunker and white-water trips down the River Neretva.

- Jablanica – 20 km west of Konjic, has a notable necropolis and the railway bridge scene of the Battle of Neretva.

- Mostar – 30 km south of Jablanica, rightly famous for its picturesque old bridge and Ottoman centre. You'll most likely pass through en route to the Adriatic coast.

- Belgrade – The capital of Serbia, 200 km northeast of Sarajevo, is a lively cosmopolitan city.

- Previous Destinations of the month

- Has custom banner

- Has map markers

- Has mapframe

- Airport listing

- Maps with non-default size

- Articles with dead external links

- Do listing with no coordinates

- Buy listing with no coordinates

- Sleep listing with no coordinates

- Has warning box

- Listing with multiple email addresses

- Guide cities

- Guide articles

- City articles

- Sarajevo Region

- All destination articles

- Has Geo parameter

- Pages using the Kartographer extension

Navigation menu

Introducing Bosnia and Herzegovina

About bosnia and herzegovina.

- Images of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History, language & culture

- Weather & geography

- Doing business & staying in touch

Plan your trip

- Travel to Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Where to stay

While you’re there

- Things to see & do

- Shopping & nightlife

- Food & drink

- Getting around

Before you go

- Passport & visa

- Public Holidays

- Money & duty free

Book your flights

- Sarajevo International Airport

Bosnia and Herzegovina travel guide

Despite a tumultuous background, Bosnia-Herzegovina has emerged as a compelling, multi-faceted travel destination. Most notable amongst the country's many charms is its lush, mountainous landscape, best seen from the vantage point of one of its national parks.

Bosnia-Herzegovina still bears the legacy of war, but there are plenty of positives to take from the country's urban centres, especially the cosmopolitan capital of Sarajevo. With its rich history and lively nightlife, this diverse city has become one of Europe's most curious, unique capitals. The old town of Sarajevo is divided between the evocative Ottoman quarter of historic mosques, little streets filled with cafes and craft workshops, and the trendy Austria-Hungarian quarter built during the late 19th century – truly a case of east meets west.

Sarajevo also has several museums explaining its history, while climbing the steep hills rewards you with a stirring view of the city. One oddity is the colossal bobsleigh track from the 1984 Winter Olympics that runs through the forests of Trebevic mountain; it was destroyed during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1990s and is now a canvas for local street artists.

Beyond Sarajevo, much of the country is relatively undeveloped, but there are several historic fortresses to see, no shortage of splendid old mosques, and a number of monasteries and Catholic shrines. The second city (at least by reputation), Mostar is also increasingly popular with tourists. Perhaps above all else, it is the city’s 16th century Ottoman bridge that symbolises both the past and a positive new beginning for the country. Destroyed during the war, it has since been painstakingly reconstructed, and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.

51,129 sq km (19,741 sq miles).

3,798,672 (UN estimate 2016).

75.6 per sq km.

Federal democratic republic.

Chairman of the Presidency Denis Becirovic since 2024.

Prime Minister Borjana Kristo since 2022.

Travel Advice

Before you travel.

No travel can be guaranteed safe. Read all the advice in this guide. You may also find it helpful to:

- see general advice for women travellers

- read our guide on disability and travel abroad

- see general advice for LGBT+ travellers

- read about safety for solo and independent travel

- see advice on volunteering and adventure travel abroad

Travel insurance

If you choose to travel, research your destinations and get appropriate travel insurance . Insurance should cover your itinerary, planned activities and expenses in an emergency.

About FCDO travel advice

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office ( FCDO ) provides advice about risks of travel to help you make informed decisions. Find out more about FCDO travel advice .

Follow and contact FCDO travel on Twitter , Facebook and Instagram . You can also sign up to get email notifications when this advice is updated.

This information is for people travelling on a full ‘British citizen’ passport from the UK. It is based on the UK government’s understanding of the current rules for the most common types of travel.

The authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina set and enforce entry rules. If you’re not sure how these requirements apply to you, contact the Bosnia and Herzegovina Embassy in the UK .

COVID-19 rules

There are no COVID-19 testing or vaccination requirements for travellers entering Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Passport validity requirements

To enter Bosnia and Herzegovina, your passport must:

- have a ‘date of issue’ less than 10 years before the date you arrive – if you renewed your passport before 1 October 2018, it may have a date of issue that is more than 10 years ago

- have an ‘expiry date’ at least 90 days after the date you plan to leave

Check with your travel provider that your passport and other travel documents meet requirements. Renew your passport if you need to.

You will be denied entry if you do not have a valid, undamaged travel document or try to use a passport that has been reported lost or stolen.

Visa requirements

You can travel without a visa to Bosnia and Herzegovina for up to 90 days within a 6-month period. This applies if you travel:

- as a tourist

- to visit family or friends

- to attend business meetings, cultural or sports events

- for short-term studies or training

For all other types of travel, check the conditions for temporary residence or contact the Bosnia and Herzegovina Embassy in the UK .

Make sure you get your passport stamped on entry and exit.

If you’re a visitor, border guards will look at your entry and exit stamps to check you have not overstayed the 90-day visa-free limit. If you do not have a stamp, the Border Police may fine you when you leave.

Staying longer than 90 days in a 6-month period

If you want to stay longer than 90 days within a 6-month period, apply for a residence permit. You must provide a document showing that you have no criminal record in the UK. The British Embassy is not able to issue such a document. You can get a copy of your police records before you travel.

For more information, see the Bosnia and Herzegovina government’s page about residency and work permits .

Vaccine requirements

For details about medical entry requirements and recommended vaccinations, see TravelHealthPro’s Bosnia and Herzegovina guide .

Registering your stay

All foreign nationals must register with the police within 72 hours of arrival, at a local police station. Hotels and some hostels will usually register their guests. If your accommodation is not arranging this, you need to contact the nearest field centre (‘terenski centar’) for the Service for Foreigners’ Affairs .

Travelling with children

Children aged 17 and under who are travelling unaccompanied or with an adult other than their parents, must carry a notarised letter giving permission for travel. The letter must be signed by a parent or guardian and give the name of the accompanying adult.

This also applies if only one parent is accompanying the child, particularly if they have a different surname to the child’s.

For further information contact the Embassy of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the UK .

Customs rules

There are strict rules about goods you can take into and out of Bosnia and Herzegovina . You must declare anything that may be prohibited or subject to tax or duty.

There is a high threat of terrorist attack globally affecting UK interests and British nationals, including from groups and individuals who view the UK and British nationals as targets. Stay aware of your surroundings at all times.

UK Counter Terrorism Policing has information and advice on staying safe abroad and what to do in the event of a terrorist attack. Find out how to reduce your risk from terrorism while abroad .

Terrorism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Terrorist attacks in Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot be ruled out.

Previous attacks have included firearms attacks on government, law enforcement interests and the public. Attacks could be indiscriminate, including in places visited by foreigners.

Political situation

Public protests occur from time to time and can cause traffic disruption. Protests are normally peaceful. There is a risk of violent incidents linked to locally controversial issues, usually from the conflict of the 1990s.

There has been an increase in anti-UK rhetoric from some politicians in the Republika Srpska (one of the entities that makes up the State of Bosnia and Herzegovina). This could translate into wider anti-UK sentiment. Monitor local media so you can avoid planned political demonstrations and move away if you see protestors gathering.

Protecting your belongings

Beware of pickpockets and bag-snatchers on public transport and in the tourist and pedestrian areas of Sarajevo and other cities. Make sure personal belongings, including your passport, are secure. Obvious displays of wealth, including large quantities of cash or jewellery and luxury vehicles can make you a target for opportunist thieves.

There has been an increase in thefts from cars in popular tourist areas in and around Sarajevo, particularly on Mount Trebevic. Make sure your vehicle is locked and your belongings are out of sight. Take particular care in areas popular with foreign tourists and in crowded public venues.

Organised crime

Incidents of violence between organised crime groups can happen, including shootings. You are unlikely to be targeted. Remain vigilant and follow the advice of the police in the event of an incident.

Old landmines and unexploded weapons

Landmines and other unexploded weapons remain from the 1992 to 1995 war. While highly populated areas and major routes are largely clear, there is still a risk in less populated and rural areas. Do not step off roads and paved areas without an experienced guide. Take care near:

- the former lines of conflict

- the edge of roads

- the open countryside

- destroyed or abandoned buildings (including in towns)

- neglected land

- untarred roads

- woods and orchards

For further information, see Mine Action Centre .

Laws and cultural differences

Personal id.

Always carry your passport or official photo ID with you. You must be able to show some form of identification if required, including when checking into hotels. For more information, see the Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina .

Dealing with the police

Local police do not always have English language skills and you may need the services of a translator .

Ramadan is a holy month for Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The dates vary by year and country.

You should:

- check opening hours of shops and restaurants

- be aware that if hotels and restaurants are providing food or drink in fasting hours, they may separate you from other guests

- follow local dress codes – clothing that does not meet local dress codes may cause more offence at this time

Get more advice when you arrive from your tour guide, hotel or business contacts.

LGBT+ travellers

Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but LGBT+ communities continue to report incidents of discrimination and even violence. Showing affection in public is likely to be frowned upon and may receive unwelcome attention.

Read more advice for LGBT+ travellers .

Outdoor activities and adventure tourism

Check that your travel and medical insurance cover you for any adventure activities and sports.

Diving off Mostar bridge is dangerous and has resulted in serious injuries and fatalities.

Take care when white-water rafting in rivers or close to waterfalls. Currents can be extremely strong.

Transport risks

Road travel.

If you are planning to drive in Bosnia and Herzegovina, see information on driving abroad and check the rules of the road in the RAC’s Bosnia and Herzegovina guide . The guide lists driving regulations and other legal requirements you need to be aware of.

Your UK driving licence is valid as long as you’re driving your own vehicle or a car hired outside of Bosnia and Herzegovina. If you’re renting or using someone else’s vehicle within the country, you must also have the 1968 version of the international driving permit ( IDP ) with you in the car.

You cannot buy an IDP outside the UK, so get one before you travel.

Check if you need a UK sticker to drive your car outside the UK .

If you’re staying longer than 6 months, you will need to get a local driving licence. See living in Bosnia and Herzegovina for more details.

Contact the Bosnia and Herzegovina Embassy in the UK if you have questions about bringing a vehicle into the country. The British Embassy will not be able to help if you do not have the correct documentation.

If you are involved in an accident, stay at the scene and do not move your vehicle until the police arrive. Traffic police can impose on-the-spot fines for any traffic offence.

Border insurance

It’s illegal to drive without at least third-party insurance. The Border Police can request printed documents to show you have it.

Check your insurance is valid in Bosnia and Herzegovina. If it’s not, you can buy ‘border insurance’ at the crossings at:

- Crveni Grm (south)

- Izacici (west)

- Karakaj and Raca (east)

- Samac (north-east)

- Zubci (south-east)

Winter equipment requirements

Take care when travelling outside the main towns and cities in winter, as road conditions can worsen quickly.

Between November and April you must:

- have tyres with an MS, M+S or M&S mark and a stylised symbol of a snowflake – the tread should be at least 4 millimetres deep

- carry snow chains and use them when road signs tell you to

Official taxis in Sarajevo and the major towns are well-regulated and metered. Taxi drivers from the Republika Srpska might refuse to drive to a destination in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the same from the Federation to the Republika Srpska.

Taxi drivers at Sarajevo airport taxi rank may try to charge a ‘fixed price’ fare, rather than use a meter, or charge for luggage. Make sure you agree a price before setting off. Better deals may be available by pre-booking a taxi from an established taxi service.

Do not use unlicensed taxis.