What Is The Bitcoin Travel Rule?

Home » Articles » What Is The Bitcoin Travel Rule?

- Published on November 15, 2023

Share this article

Bitcoin, as it states in the white paper, is peer-to-peer electronic cash; it has no central issuer since anyone who can mine can earn it, while those who wish to acquire it can do so by trading something of value with another person. These trades can be conducted as fiat to Bitcoin trades, trading your time and labour for Bitcoin or selling goods for Bitcoin.

Peer-to-peer markets for Bitcoin exist, as do a few Bitcoin circular economies where trades like those mentioned above are becoming the norm, but these users or Bitcoiners are exceptions, not the rule.

The overwhelming majority of people who wish to acquire Bitcoin do so by heading towards a regulated entity such as an exchange or fintech company and conducting their trades within these regulated walled gardens.

While exchanges and fintech apps make it nearly frictionless and easy to exchange your fiat for Bitcoin or vice versa, they are not without their trade-offs. To access these walled gardens, you need to provide proof of your identity, abide by a host of KYC and AML rules, and run the risk of associating all your purchases with your identification.

Exchanges becoming a choke point instead of a gateway

Exchanges work well until they don’t, and we’ve seen examples of exchanges going bust, closing down people’s accounts, blacklisting users and having private user data leaked, putting their customers at risk.

These are very real concerns when you deal with a 3rd party custodian and should not be taken lightly; they are a central point of failure and pressure and make it easy for regulators and governments to put a chokehold on a local Bitcoin market.

If the vast majority of a particular country’s Bitcoin trading happens on a local platform, shutting down or limiting that entity’s ability to offer Bitcoin trades can be devastating. It also enables the ability to easily 6102 individuals Bitcoin if users leave their funds with a service provider.

While this might sound like hyperbole to you now since we haven’t had an example of mass confiscation of funds or widespread blacklisting of users, the building blocks for it are surely starting to take shape with the update of the travel rule now starting to apply to Bitcoin transactions.

What is the Bitcoin Travel Rule?

The Bitcoin travel rule, officially known as the FATF (Financial Action Task Force) Recommendation 16, is a regulatory requirement claiming its aim is to combat money laundering and terrorist financing by enhancing transparency in cryptocurrency transactions.

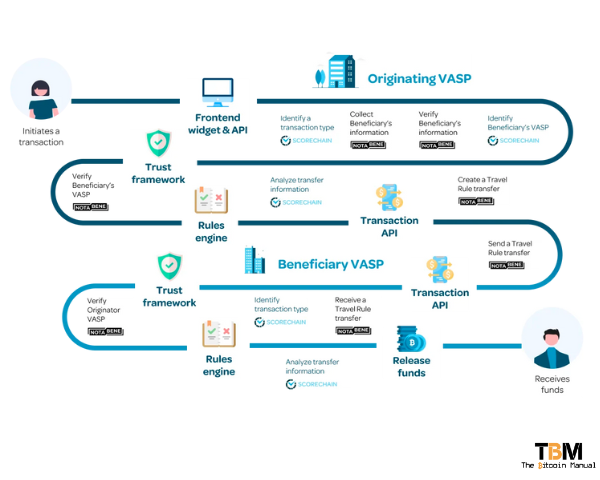

This rule, adopted by the FATF in 2019, mandates that virtual asset service providers (VASPs), such as cryptocurrency exchanges and wallet providers, exchange certain customer information with each other when transferring virtual assets above a specified threshold.

Key components of the Travel Rule

The Bitcoin travel rule encompasses several crucial elements that contribute to its effectiveness:

- Customer Identification: VASPs are mandated to collect and verify customer information, including names, addresses, and identification numbers, for both the sender and recipient of cryptocurrency transactions.

- Transaction Threshold: The rule applies to transactions exceeding a specified threshold, which varies depending on the jurisdiction. In some regions, the threshold is set at $1,000, while others may have higher or lower limits.

- Information Sharing: VASPs must exchange customer information with each other when sending or receiving cryptocurrency transactions above the threshold. This information exchange enables authorities to track the movement of funds and identify potential red flags.

- Sanction Screening: VASPs are required to check counterparties against sanctions lists to prevent transactions with individuals or entities under sanctions.

- Due Diligence: VASPs must conduct due diligence on counterparties to assess their risk profiles and ensure compliance with the travel rule.

The original (fiat) Travel Rule

Published in January 1996, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Advisory presented the original Travel Rule:

A Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) rule [31 CFR 103.33(g)]—often called the “Travel” rule—requires all financial institutions to pass on certain information to the next financial institution in certain funds transmittals involving more than one financial institution. ( FinCEN 1997 )

The rules remained unchanged for several years and never applied to Bitcoin for the first decade of its existence. Only i n 2019 did the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) update its recommendations to extend them, including the Travel Rule, to virtual assets (VAs) and VA service providers (VASPs).

Since the expansion of the travel rule in 2019, several countries — including Germany , Singapore , Switzerland , Canada , the United States , South Africa , the Netherlands , Estonia and a few more — have adopted or introduced legislation that mirrors these FATF-driven AML compliance obligations.

Even if the travel rule doesn’t apply to you now, consider it a work in progress and plan accordingly. Like anything regulatory, the larger economies set the rules, and the rest eventually follow.

The essence of the travel rule

The core principle of the Bitcoin travel rule lies in its ability to trace the origins and recipients of cryptocurrency transactions, thereby enabling authorities to identify and investigate potentially illicit activities.

By requiring VASPs to collect and share customer information, the rule seeks to bridge the anonymity gap inherent in Bitcoin transactions, making it more difficult for individuals to access the wider Bitcoin network via exchange on-ramps.

The claim is that by adding more onerous requirements to send and receive Bitcoin when using an exchange, there is less chance of criminals using exchanges to liquidate the proceeds of crime. The truth is criminals can always find ways around this, such as selling on P2P markets, purchasing KYC accounts that are for sale through online markets, and using complex mixing services and stablecoins to conduct business.

The only ones affected by the travel rule are law-abiding citizens who will need to provide even more information every time they withdraw funds to an on-chain wallet or those sending on-chain Bitcoin to exchange to liquidate it to acquire cash.

The travel rule will not only increase your KYC footprint but also make it harder for you to hide your on-chain footprint, which can put you at risk should that data ever be leaked.

Impact of the Bitcoin Travel Rule

Implementing the Bitcoin travel rule will significantly impact the Bitcoin industry, introducing a new layer of compliance and accountability and making it more expensive to offer compliant Bitcoin services. While some industry participants have expressed concerns about the rule’s potential to hinder innovation and reduce privacy, others view it as a necessary step towards legitimising Bitcoin and fostering a more responsible financial ecosystem.

Those who welcome it also see the added regulation as another barrier to entry, reducing the possibility of future competition entertaining the space and securing their place in the current regulated Bitcoin market.

Under the crypto Travel Rule, VASPs and Bitcoin businesses must share customer information when transferring Bitcoin, or digital assets, above the threshold.

This personally identifiable information (PII) must include: (Note this may vary based on your country)

Sender reporting requirements:

Recipient reporting requirements:

What are the concerns around the travel rule?

Applying the travel rule to Bitcoin is not without its controversies and brings a lot of concerns to the Bitcoin community.

- The Travel Rule can be considered a breach of individuals’ privacy rights.

- There’s a common belief that the regulations will slow down blockchain development in the EU and halt innovation in the industry.

- The negative impact comes from the requirement to collect data on the transactions, which could make crypto exchange activities slower and more expensive.

- Technical experts are concerned about the security of the data. More specifically, combining the data with information from the Crisis Management Platforms and the European Commission, European Central Bank, and European Banking Authority could make it vulnerable to cyber-attacks.

- There is an additional risk from illicit or fake VASPs who might use legislation as an opportunity to collect user data, as well as from oppressive regimes seeking to control legitimate users of Bitcoin as a method of moving funds outside the system.

- Travel Rule requires VASPs to share the personal information of a transaction’s sender and recipient with other financial businesses or VASPs. Since the FATF does not advise the use of any specific data-sharing technology, there is no single protocol or network for data transfer. That is why several third-party networks for encrypted data transfers exist, including OpenVASP, Shyft, and Trisa, which only add to the complexity, the data footprint and the chances of data leaks.

The travel rule could be part of a spot ETF push.

If the travel rule makes it harder for exchange users to move funds in and out of platforms and makes it more expensive for exchanges to operate, why would exchanges want to comply with this added regulation?

The obvious reason would be they do not want to be shut out of large markets like the U.S. and are willing to play ball to access the customer base, but it could also be a play for a future approval of a spot ETF. If one is approved, regulated custodians will be required to custody the Bitcoin on behalf of these ETFs, and these exchanges will need to comply with strict regulations on the type of coins they hold and how they move funds in and out of their service if they want to capture some of that spot ETF inflows.

To help make exchanges more attractive, we’ve already seen some of them push for the creation of interoperable systems for compliance. Paxos, with partner members including Coinbase, Circle, Gemini and Kraken, introduced Travel Rule Universal Solution Technology.

This initiative aims to aid exchange compliance in the U.S. and beyond, with exchanges obliged to meet security and privacy requirements and create platforms that are preferred custodians for ETF-managed funds.

Keeping your Sats safe requires secrecy.

Travel Rule enforcement is simultaneously a significant milestone and the biggest setback for Bitcoin, depending on how you see the asset. If you’re only in it for the capital appreciation in fiat terms, you would have no issue with these rules since you never planned on spending or using the funds outside an exchange, and the only reason you hold Bitcoin is to sell it for fiat later.

If you only use Bitcoin as a trade, and the funds remain in a walled garden and trust a third-party custodian, these rules won’t affect you. You may welcome the rules since they make it harder for capital to flow in and out of exchanges and could drive up volatility in these markets.

Additionally, the building of regulated walled gardens for Bitcoin could be the base needed for the approval for a spot ETF, which will bring institutional money into the market and pump ye o’l bags.

On the flip side, the Bitcoin travel rule represents another step backwards in improving financial privacy in the Bitcoin realm. Adding more personal information relayed on transactions facilitates traceability, putting users at risk. That data could fall into the hands of hackers who could target these users with online or in-person attacks or used by governments who wish to place oppressive measures on capital , leaving their failing economies.

If you believe in self-covering money and financial privacy, you first should accept that exchanges will not be friendly towards your ideals and use of Bitcoin. You may need to cut ties with exchanges, sell off your KYC Bitcoin and re-buy on P2P markets. P2P market premiums might not be so expensive in the future when compared to centralised exchanges, which might need to increase their fees to pay for the additional operational costs, making P2P purchases more attractive .

If you do remain with a KYC exchange, you will need to consider consolidating your coins in an on-chain wallet and mix it with the mixing service of your choice later so your coins cannot be traced back to you and your future spending habits are no longer monitored.

While you can never get rid of the initial purchase data from the exchange, those who have that data will not be able to follow your funds after they’ve left the exchange.

Disclaimer: This article should not be taken as, and is not intended to provide any investment advice. It is for educational and entertainment purposes only. As of the time posting, the writers may or may not have holdings in some of the coins or tokens they cover. Please conduct your own thorough research before investing in any cryptocurrency, as all investments contain risk. All opinions expressed in these articles are my own and are in no way a reflection of the opinions of The Bitcoin Manual

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don't subscribe All new comments Replies to my comments Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

- Bitcoin Legislation , regulation

Related articles

You may also be interested in.

What Is The Sequentia Side Chain?

Bitcoin is optimised for security and reliability. Its design, while robust, has inherent limitations when it comes to scalability. The blockchain, the underlying technology, can

What Is Fractal Bitcoin?

It feels like nearly a lifetime ago now that Ordinals were making headlines and stirring up all sorts of arguments about how to use block

Switch themes

Sign up to our newsletter.

- Privacy policy

- Terms and conditions

- +40-200-4286-09

- [email protected]

- 83 Barbara St, Newark, NJ 07105

Hot daily news right into your inbox.

The Circle Pressroom

Press release, circle is first global stablecoin issuer to comply with mica, eu’s landmark crypto law.

Circle’s French entity is launching USDC and EURC issuance in the EU in compliance with one of the world’s most comprehensive regulatory regimes for digital assets

PARIS – July 1, 2024 – Circle , a global financial technology firm and the issuer of USDC and EURC , has today announced that it has become the first global stablecoin issuer to achieve compliance with the European Union's landmark Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulatory framework.

This achievement was enabled by the company’s attainment of an Electronic Money Institution (EMI) license (’agr ément en qualité d'établissement de monnaie électronique) from the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), the French banking regulatory authority. With this license, both USDC and EURC are now being issued in the EU in compliance with MiCA’s regulatory obligations for stablecoins or e-money tokens, which took effect yesterday, according to the law today and subject to potential clarifications on the interpretation of the law by the European Commission.

As part of attaining compliance with this comprehensive regulatory regime, Circle Mint is officially available for business customers in Europe. Equipped with local banking capabilities, Circle Mint France provides near-instant and cost-effective access to mint and redeem USDC and EURC throughout the European market.

“Since our founding, Circle has sought to build durable, compliant, and well-regulated infrastructure for stablecoins, and our adherence to MiCA, which represents one of the most comprehensive crypto regulatory regimes in the world, is a huge milestone in bringing digital currency into mainstream scale and acceptance,” said Jeremy Allaire, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer at Circle. “By working closely with French and EU regulators, we are now able to offer both USDC and EURC as fully-compliant dollar and euro stablecoins to the European market, unlocking the enormous potential of digital assets to transform finance and commerce.”

"Achieving MiCA compliance through our French EMI license is a significant step forward, not just for Circle, but for the entire digital financial ecosystem in Europe and beyond," said Dante Disparte, Chief Strategy Officer and Head of Global Policy at Circle. "As digital assets become increasingly integrated into the mainstream financial landscape, it is essential that we establish robust, transparent frameworks to promote trust and adoption. Today’s announcement further reinforces our commitment to building a more inclusive, compliant future for internet finance."

"Circle's success in obtaining this license is the result of close collaboration over many months between the regulatory teams in charge of ACPR authorizations and the Circle France team," said Coralie Billmann, Managing Director of Circle France.

Of the top 10 stablecoins by market capitalization, only USDC is currently MiCA-compliant. This milestone underscores Circle's commitment to regulatory compliance for dollar and euro stablecoins. The company's proactive approach to meeting high standards of security, transparency and oversight will help drive the mainstream adoption of regulated digital currencies.

This marketing communication is issued by Circle Internet Financial Europe SAS, a licensed Electronic Money Institution and registered Digital Assets Services Provider in France. White Papers relating to electronic money tokens that we issue in the European Economic Area (EEA) ("EMT") are published and available on our website . Holders of EMT have the right of redemption against the issuer at any time and at par value. Contact: Web: http://www.circle.com | Email: [email protected] | Phone number : +33 (1) 59000130

Get Daily Travel Tips & Deals!

By proceeding, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Open-Jaw and Circle Fares

Ed Hewitt started traveling with his family at the age of 10 and has since visited dozens of countries on six continents. He wrote for IndependentTraveler.com for more than 20 years, producing hundreds of columns on travel and offering his expertise on radio and television. He is now a regular contributor to SmarterTravel.

An avid surfer and rower, Ed has written about and photographed rowing competitions around the world, including the last five Olympic Games.

He's passing his love of travel on to the next generation; his 10-year-old son has flown some 200,000 miles already.

Travel Smarter! Sign up for our free newsletter.

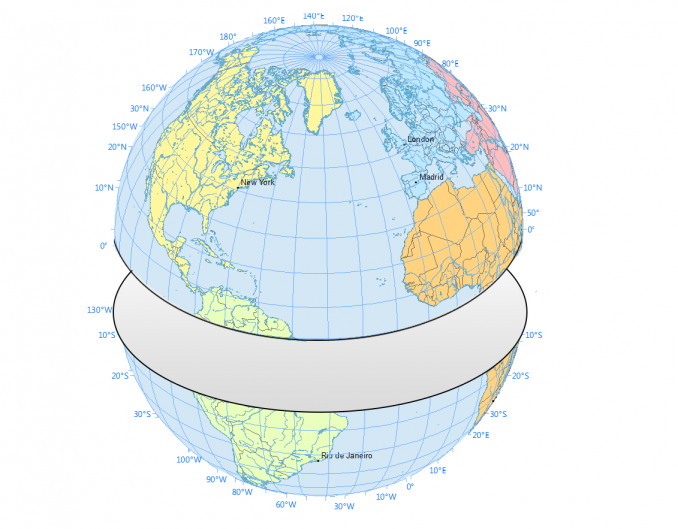

When is a round trip not a round trip? When it’s a circle or open-jaw itinerary.

Thanks to the airlines’ complicated and arcane fare structures, roundtrip flights almost always cost less than the sum cost of two one-way trips on the same route. (Discount airlines are a notable exception to this rule.) And most round trips go from Point A to Point B and back again.

But what if you need to do some traveling at your destination, and it’s more convenient to fly home from a different airport? Or if you need to hit two or more cities in a short span of time, and want to do it in a single trip? If either situation applies to you, you may want to consider an open-jaw or circle ticket. Read on to learn how these special fares could save you money on your next multi-city itinerary.

The Open Jaw An open-jaw flight is one that, in the simplest terms, flies from Point A to Point B, then from Point C back to Point A. Points B and C are often neighboring airports, or at least in the same general area. A sample open-jaw itinerary might be a flight from Atlanta to Seattle on the way out and from Portland, OR to Atlanta on the way back.

Another open-jaw scenario is to fly into and out of the same destination city, but your starting and finishing points are different, thus: Fly Point A to Point B; then fly Point B to Point C.

An open jaw is ideal for travelers who are planning to cover a lot of ground during their trip and who don’t want to waste time returning to their original airport. Perhaps you fly into San Francisco and then drive down the coast of California to Los Angeles; an open-jaw fare would allow you to fly home out of LAX instead of making your way back up to San Francisco. Open jaws are also useful for cruise passengers whose sailings embark and disembark in different ports.

Despite the fact that an open-jaw itinerary isn’t quite a classic round trip, most airlines treat it as such and charge you half the roundtrip fare of what each leg of the trip would cost you. So if the Atlanta – Seattle round trip would cost $400 and the Portland – Atlanta round trip would cost $500, you end up paying $200 for the first leg and $250 for the second leg, for a total of $450 roundtrip. The resulting total fare will typically offer considerable savings over the cost of two separate one-way flights.

There is such a thing as a double open jaw — Point A to Point B on the way out, and then Point C to Point D on the return. While this is usually more expensive than a traditional open jaw, it may still save you money over two separate one-way flights.

The Circle A circle itinerary typically begins and ends in the same city, but includes at least three separate flights that take you to two or more different cities without the overland portions of the open jaw.

Example: Fly from New York to Detroit, then Detroit to Houston, then Houston to New York. (Feel free to add Points D, E, F and beyond, but make sure you start and end at your original city — New York in this example.)

Circle itineraries usually permit a maximum of two stopovers and are priced as a series of one-way flights. (Circle fares may not save you as much as an open jaw.) Still, circle fares qualify you for discounted fares, and you may even find that the fares on the separate legs of your flight add up to less than a pure roundtrip fare. This is especially true on popular long-haul routes.

Exceptions and Rules Open Jaw The most common restriction on an open-jaw itinerary is that the segment of your trip that you don’t fly (the Seattle-Portland leg in our example) must be shorter than the shortest leg of the trip that you do fly.

So, for example, if you flew from Atlanta to Seattle, then drove cross-country to New York, then flew back to Atlanta, you couldn’t qualify for the open-jaw discount, as the distance from Seattle to New York is much greater than the distance from New York to Atlanta.

Circle Fares Restrictions and rules on circle itineraries vary by airline, but usually take one of the two following forms, both a variation on the old “Saturday night stay” rules:

1. You may not begin travel from the farthest geographical point of your trip until the first Sunday of your trip. Note that it is the farthest geographical point, not the place you stay the longest or schedule in the middle of your trip.

2. You may not begin the last leg of your trip until the first Sunday after the beginning of your trip.

The difference between the two is critical: in the first instance, the order in which you visit the cities is extremely important. In the latter instance, it is much less so.

If your airline has different rules for different segments of your trip, the whole trip will generally be subject to the most restrictive ones. So, for example, if one fare requires a 14-day advance purchase and the other a 21-day advance purchase, you’ll need to book 21 days ahead in order to get the discounted circle fare.

How to Find Open Jaw and Circle Fares Luckily, open-jaw and circle fares are not too difficult to find. Most online booking engines and airline Web sites can recognize a circle or open-jaw itinerary, and price them accordingly; just look for the multi-city search option. It might still be worth checking with your travel agent just to be sure. If prices seem high, call and ask if minor adjustments of your flight dates might help you qualify for either an open-jaw or circle itinerary.

Keep in mind, however, that these fares may not necessarily be your cheapest bet. If a discount airline serves all or part of your itinerary, check that carrier’s one-way fares to see if they can beat what the big airlines are offering. For help finding low-cost carriers around the world, check out our guides to Domestic Discount Airlines (U.S.) and International Discount Airlines .

You May Also Like

- Get the Best Airplane Seat

- Around-the-World Tickets and Fares

We hand-pick everything we recommend and select items through testing and reviews. Some products are sent to us free of charge with no incentive to offer a favorable review. We offer our unbiased opinions and do not accept compensation to review products. All items are in stock and prices are accurate at the time of publication. If you buy something through our links, we may earn a commission.

Top Fares From

Don't see a fare you like? View all flight deals from your city.

Today's top travel deals.

Brought to you by ShermansTravel

Greece: 8-Nt, Small-Group Tour, Incl. Aegina,...

Amsterdam to Copenhagen: Luxe, 18-Night Northern...

Regent Seven Seas Cruises

Ohio: Daily Car Rentals from Cincinnati

Trending on SmarterTravel

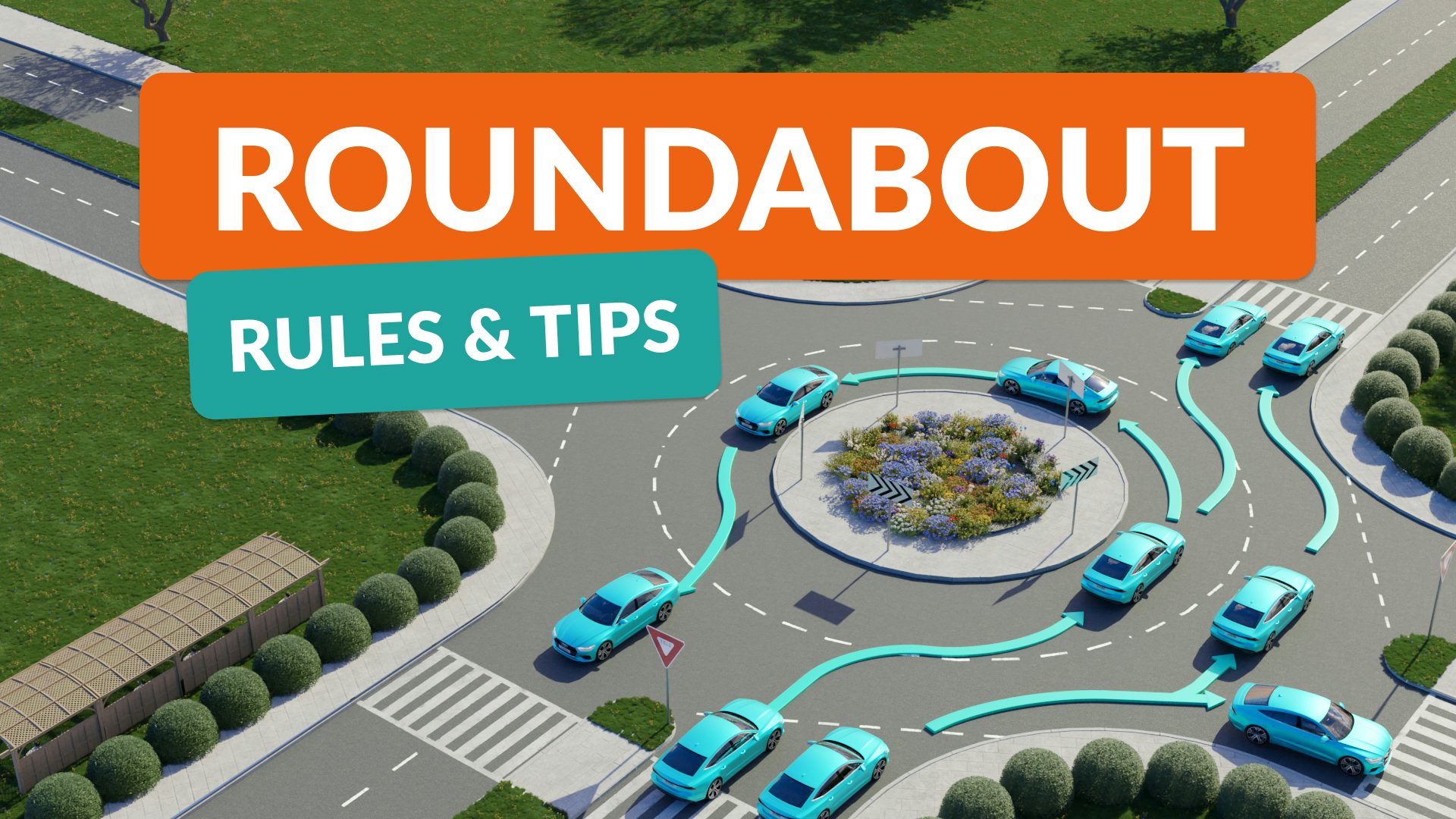

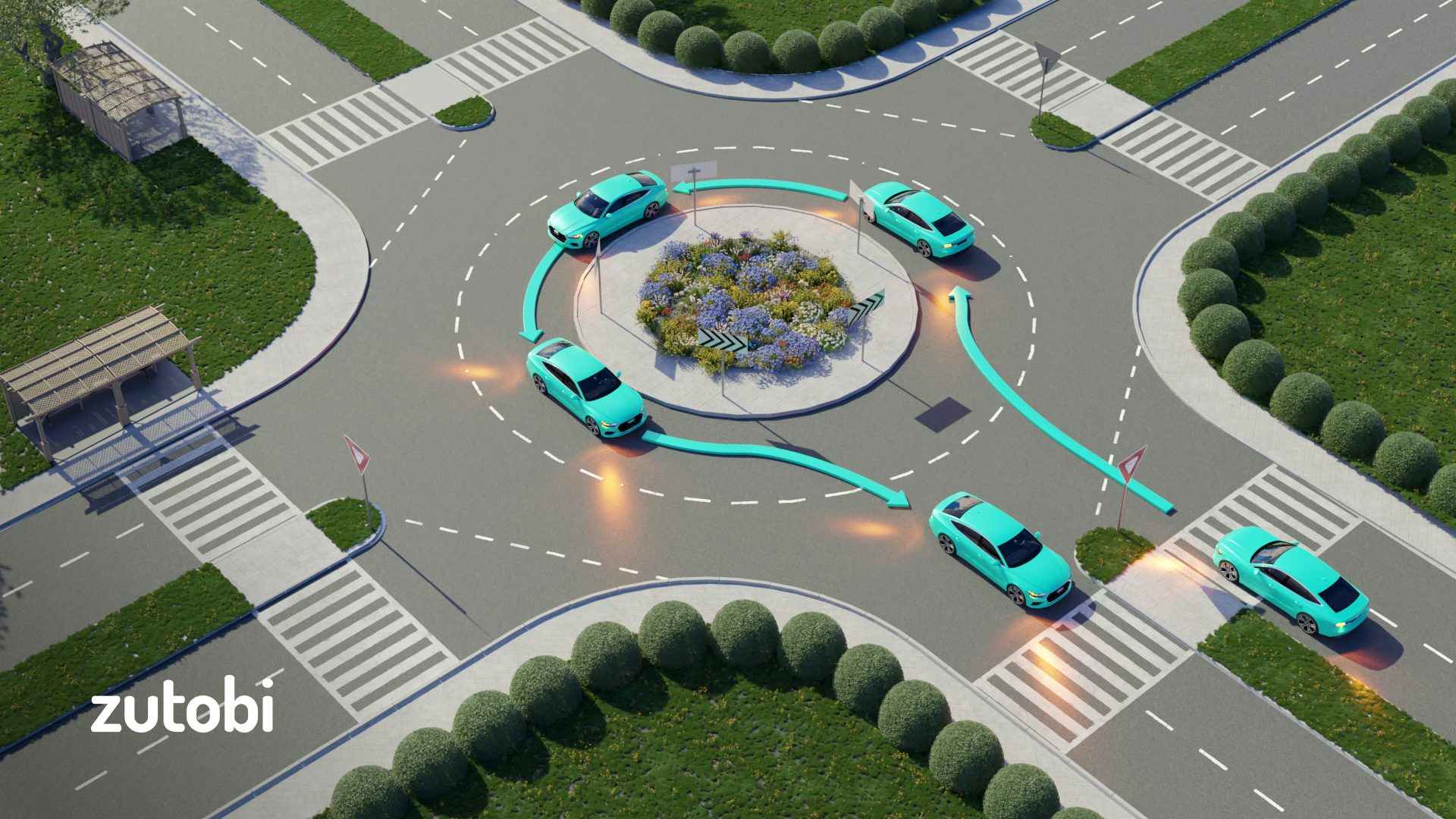

How to Use a Roundabout Correctly: Traffic Rules & Signaling

Mastering a roundabout means knowing its structure and function in maintaining safe traffic flow along with understanding the key navigation principles.

In this article, we explain:

- How to navigate roundabouts

- Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Differences between roundabouts and traffic circles

What Is a Roundabout?

A roundabout is a circular intersection where vehicles move counterclockwise around a central island. There are no traffic lights to regulate the flow of cars. Instead, circulating vehicles have the right-of-way , and those entering must yield to them.

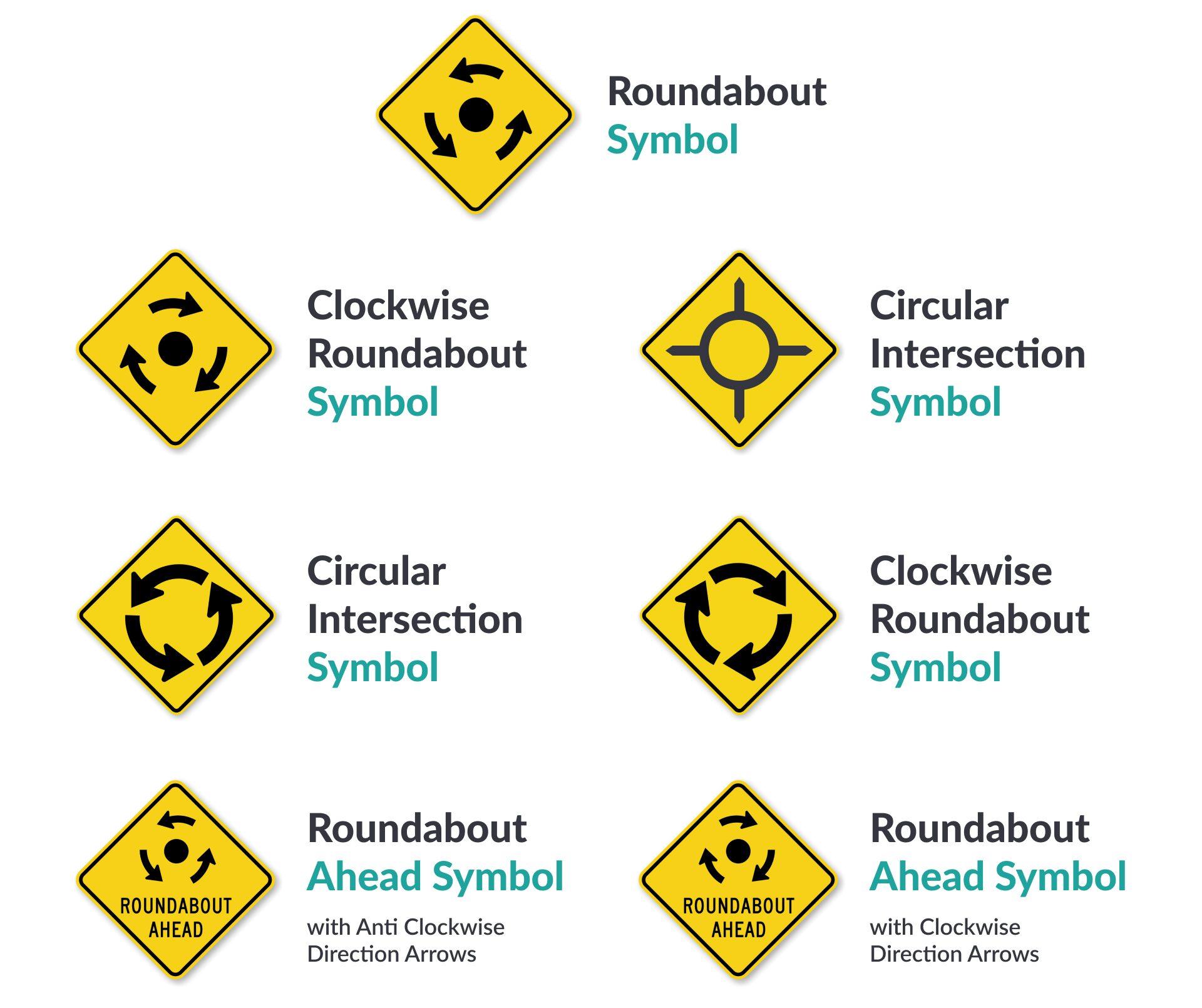

Roundabout Signs

Multi-lane vs. Single-lane Roundabouts

Multi-lane and single-lane roundabouts adhere to the same traffic rules. However, in multi-lane roundabouts, drivers must choose their entry lane based on their intended exit. Thus, to turn right at the intersection, a driver must select the right lane.

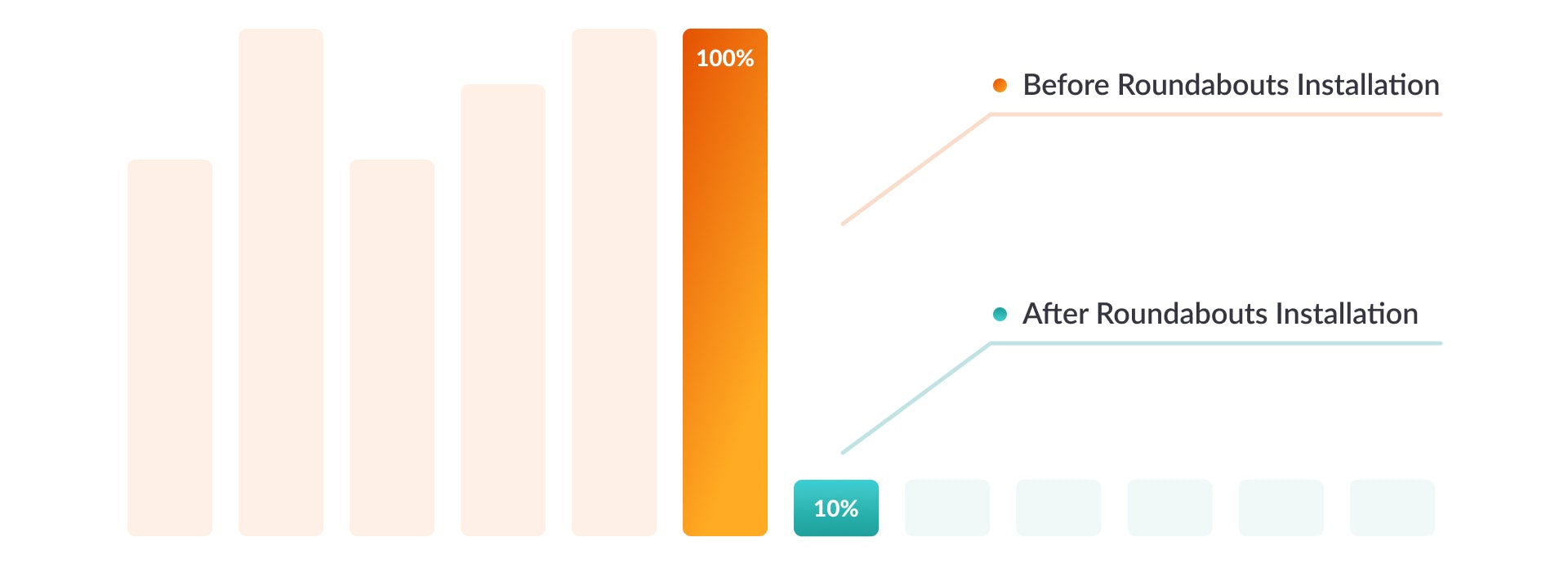

Why Roundabouts are Useful

- Enhanced Safety: Roundabouts minimize the risk of severe injuries from right-angle, head-on, and high-speed collisions and feature crosswalks set further from entering traffic, providing safer pedestrian routes.

- Boosted Traffic Flow: The yield-at-entry rule in roundabouts facilitates uninterrupted traffic flow and reduces unnecessary wait times.

- Diverse Circulation: Roundabouts are important for intersections used by large trucks, allowing them to navigate easily.

- Improved Sustainability: Continuous movement reduces vehicle idling, leading to lower emissions and better air quality. Also, fewer stops minimize roadway wear, prolonging its durability.

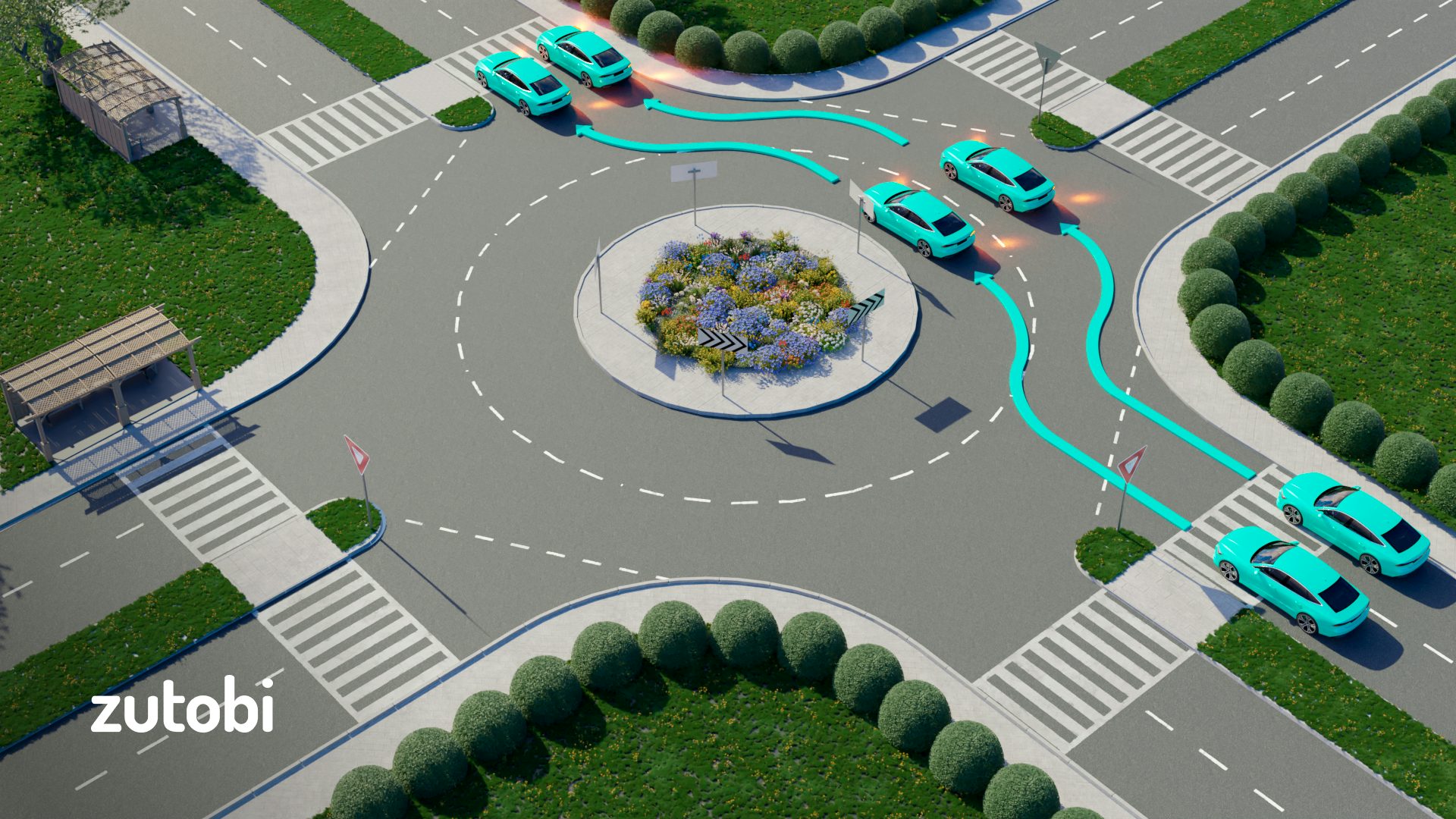

How to Use a Roundabout

Turning right.

- Choose the right-hand lane unless road markings indicate otherwise.

- Activate the right turn signal before entering.

- Keep the vehicle in the right lane and exit.

- Deactivate the right turn signal.

Going Straight

- Select either the left or right lane.

- Don’t activate any turn signals before entering.

- As you approach the intended exit, activate the right turn signal.

- Exit and deactivate the right turn signal.

Turning Left

- Enter the left lane, respecting all signage and road markings.

- Activate the left turn signal before entering.

- Remain in the left lane, following the roundabout’s curve.

- Approaching the exit, activate the right signal.

- Exit and deactivate the turn signal.

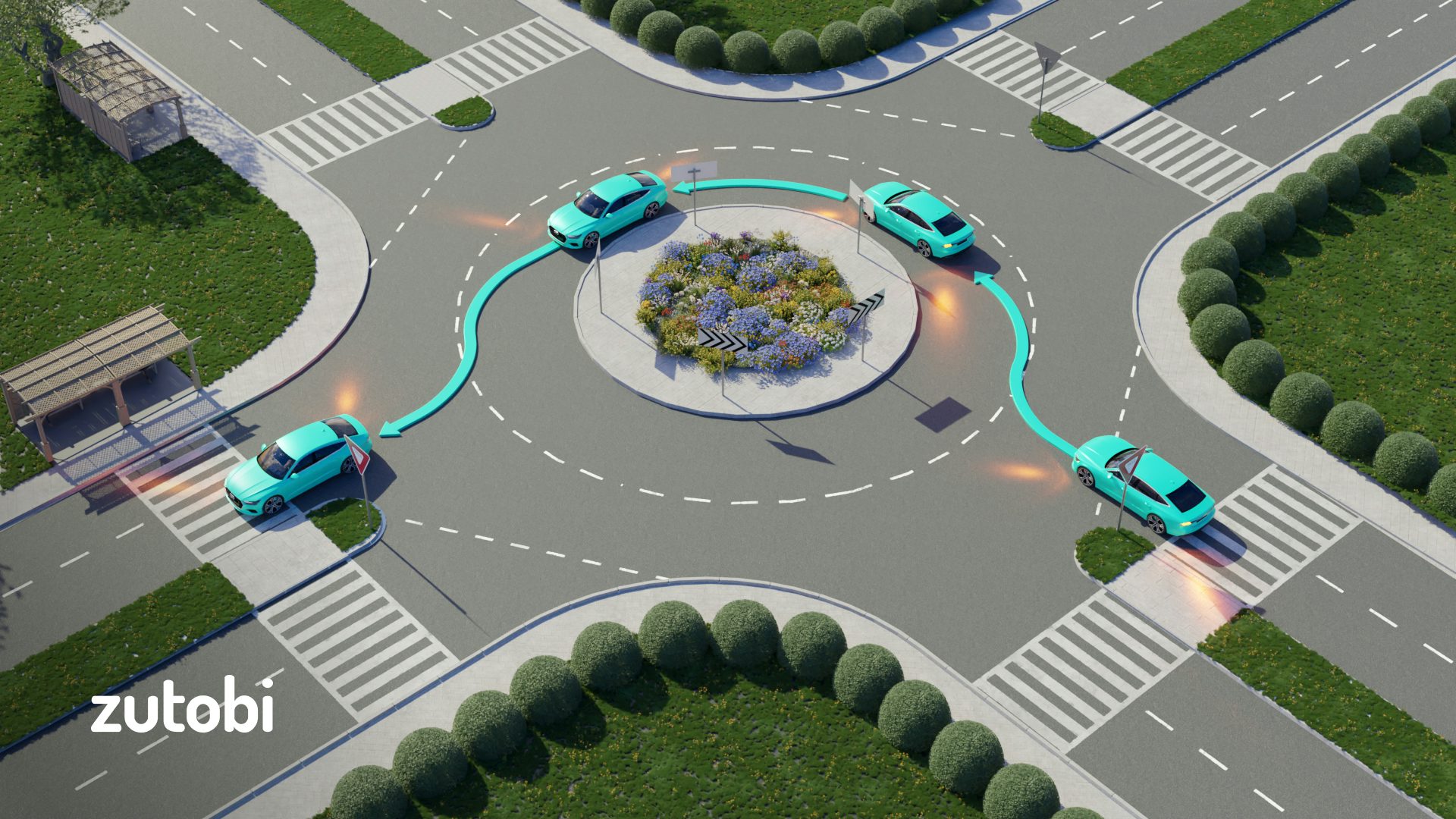

Making U-turns

- Select the left lane, adhering to road markings.

- Circulate in the left lane, passing the first and second exits.

- Nearing the third exit (from your initial entry point), activate the right turn signal.

- Leave the roundabout on the third exit and deactivate the turn signal.

When leaving the roundabout, check the mirrors and blind spots to make sure you can exit safely. If it’s unsafe to exit, circle around the roundabout and try again. As you leave, join traffic flow at a safe speed, and keep an eye on road signs and anyone on foot or bike.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in a Roundabout

Not yielding the right of way.

- Traffic Flow Disruptions: By not yielding, drivers disrupt the smooth flow of traffic, leading to sudden braking or swerving.

- Accident Risks: When multiple vehicles enter the roundabout simultaneously, not yielding the right of way can lead to T-bone collisions.

- Road User Conflicts: Failure to yield puts vulnerable road users crossing the roundabout at risk.

Speeding or Stopping

By speeding up, drivers won’t have enough time to yield to other vehicles or navigate the roundabout correctly, which leads to lane confusion and right-of-way issues.

Drivers are advised to maintain a speed limit of 15-25 mph, depending on traffic conditions and visibility. But even in heavy traffic or low visibility, stopping inside a roundabout is prohibited, as this disrupts the movement and potentially leads to collisions.

Changing Lanes

Lane changes not only disrupt the movement but also increase collision risks. Drivers should select the appropriate lane for their intended exit before entering the roundabout.

How to Change a Lane Safely

- Check Surroundings: Ensure a clear view of adjacent lanes and consistently use mirrors.

- Signal Early: Turn on your indicator to show the lane change intention, providing a warning to drivers behind.

- Monitor Blind Spots: Regularly check for not immediately visible vehicles.

- Change Decisively: When a safe gap emerges, change your lane smoothly without hesitation.

Roundabout vs. Traffic Circle

Master Roundabout Rules for your Driver’s Test

Need a sure way to nail the roundabout section of your DMV driving test? Zutobi has your back! Our app gives not only basic knowledge but also highlights specifics like signaling accurately to exit roundabouts. Get started with Zutobi today and empower your test preparation with targeted and user-friendly learning.

550+ exam-like questions

All you need to ace your test

Perfect for first-timers, renewals and senior citizens

Recommended articles

Zutobi 2024 Holiday Report: The Deadliest Holidays to be Driving

Holidays are meant to be moments of joy and celebration, but amidst the festivities, there are hidden dangers that we often overlook. every year, as countless americans hit the road to enjoy their well-deserved breaks, they unwittingly encounter risks that can turn these happy occasions into tragic events. between 2018 and 2022, an alarming 11,058 […].

Driving School Costs Report – The Cheapest and Most Expensive States

For many, the ability to drive is not just about mobility—it’s a rite of passage that symbolizes freedom and the thrill of charting one’s own course. the anticipation of sitting behind the wheel for the first time is a universal dream, yet for many aspiring drivers in the united states, this dream comes with variable […].

Distracted Driving Report – The States With the Least and Most Distracted Driving

In april 2024, the national highway traffic safety administration (nhtsa) released data for 2022 that illustrated traffic deaths due to distracted driving increased by 12 percent from 2020 but decreased compared to 2021 to 6%. every year, thousands of drivers and passengers are fatally injured as a result of distracted driving. in 2022, roughly 2,109 […].

Ace your DMV test, guaranteed

Get started

- Learner’s Permit Ultimate Guide

- Driving Test Ultimate Guide

- Traffic Lights Guide

- How to Pass the DMV Permit Test

- How to Pass the Driving Test

- Common Reasons For Failing the Road Test

- International Driver’s Permit Guide

- Driver’s License Renewal

- How to Get Your US Driver’s License

- How to Prepare for Your Road Test

- How to Get a Driver’s Permit

- Behind-The-Wheel training

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Subscription terms

- Terms & policies

- Car Practice Tests

- CDL Practice Tests

- Motorcycle Practice Tests

- Credit cards

- View all credit cards

- Banking guide

- Loans guide

- Insurance guide

- Personal finance

- View all personal finance

- Small business

- Small business guide

- View all taxes

You’re our first priority. Every time.

We believe everyone should be able to make financial decisions with confidence. And while our site doesn’t feature every company or financial product available on the market, we’re proud that the guidance we offer, the information we provide and the tools we create are objective, independent, straightforward — and free.

So how do we make money? Our partners compensate us. This may influence which products we review and write about (and where those products appear on the site), but it in no way affects our recommendations or advice, which are grounded in thousands of hours of research. Our partners cannot pay us to guarantee favorable reviews of their products or services. Here is a list of our partners .

My Travel Secret For Not Overpacking? The 10-$10 Rule

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money .

When traveling, packing less makes it easier to experience more. When you’re not weighed down by bulky bags, you have more freedom to jump on public transit or walk long distances without tiring. You’ll have fewer worries about repacking or losing items. With carry-ons only, you’ll avoid checked bag fees , waiting at the luggage carousel and the risk of lost luggage .

If you travel backpack-only, you'll be forced me to leave even more at home than you otherwise would with a full suitcase. It means sacrificing just-in-case items.

And that’s where my 10-$10 rule comes in.

What is the 10-$10 rule?

The 10-$10 rule is a packing strategy that helps you decide what to bring and what to leave behind. The premise is straightforward: If you can acquire a just-in-case item upon arrival for less than $10 and within 10 minutes, don’t pack it.

For cheap, small items that you’ll absolutely use — say a toothbrush, deodorant or underwear — pack them regardless. But for large or just-in-case items, buy them upon arrival, granted they cost less than about $10 and are easily purchasable within 10 minutes.

Under the 10-$10 rule, items you generally shouldn’t pack include:

Books (perhaps pack one, but will you really read that second one?).

First-aid kits.

Over-the-counter medications that you only sometimes use (e.g. antacid tablets or ibuprofen).

Weather-contingent items like ponchos and umbrellas (particularly if it’s not even rainy season).

Of course, the 10 minutes is key. There probably aren't drugstores in the wilderness, in which case packing something like a first-aid kit for a camping trip can make sense.

I’ve come up with this rule over the years of traveling carry-on only , and then progressing to backpack-only. When all your possessions are on your back, overpacking is not just unnecessary weight, but it makes it especially tough to sift through the items you really need.

Make the 10-$10 rule your own

The 10-$10 is more of a guideline than a rigid, one-size-fits-all rule. Embrace its spirit, and adjust the timing and dollar figure to your liking. Factors you consider might include:

A single, able-bodied adult might easily pop into a store and make a quick purchase. Others who are less mobile, or families with kids, might find that a single convenience store run exceeds 10 minutes, in which case packing more from home makes sense.

I sometimes make exceptions for an item’s size depending on the likelihood of using it.

Antihistamine cream is small and easy to pack, but I’ll never know whether I need it for a bug bite until it happens. Though such an item might never get used, I’ll more likely use it on a lakefront vacation in Florida than a trip in downtown Denver, where high elevations make it relatively bug-free.

Meanwhile, bulky items like beach towels never make the cut.

For budget-conscious travelers who can’t afford inflated hotel gift shop prices, the $10 threshold might be too high. Adjust it according to the flexibility of your budget.

As my own savings account has grown, I’m more willing to push the $10 rule higher. But in my younger years, my $10 rule was more like a $3 rule. Back then, I was more likely to pack a just-in-case umbrella, because the thought of forking over cash amidst a downpour felt wasteful. These days, I’m usually willing to gamble that it won’t rain.

Your own flexibility

If you’re picky, realize that it might take more than 10 minutes to find the item you want, in which case the 10-$10 rule doesn’t apply. I’m generally okay using any sort of skincare products. But if you demand a specific brand, pack your own.

And in some situations, like traveling with babies, taking 10 minutes to track down something like diaper cream might not be worth it when you could have packed it from home. The 10-$10 rule isn’t for you.

Items that make the 10-$10 cut on one trip might not on another. In New York City, where there’s no shortage of retailers, I’m more willing to underpack. That’s less often the case on trips to small towns or national parks where storefronts are limited.

Don’t overpack, but don’t overshop either

It’s usually okay to spend a little more than you would to buy the same things at home. I don’t mind paying the markup for sunscreen sold on the beach versus dealing with checked luggage to pack sunscreen from home.

On the other hand, watch out for wasteful spending. Once you’ve found a cheap souvenir stall, it can be tempting to buy anything under $10 — like fanny packs, sunglasses and hats. Don’t overlook the minimalist spirit of the 10-$10 rule, which is not only packing what you absolutely need — but also only buying what you absolutely need.

Benefits of the 10-$10 rule

Packing light taught me that I often don’t even need stuff I thought I did.

Hotels often supply items you might’ve packed anyway

Many hotels these days are tightening up on the free toiletries left on your bathroom counter, presumably to mitigate waste. But often, hotels still offer those freebies — you just have to ask.

On a recent stay at the Hotel Virginia Santa Barbara in Santa Barbara, Calif., the lobby attendant gave me complimentary toiletries like toothpaste and razors. I was delighted by the complimentary sunscreen at the Halepuna Waikiki by Halekulani in Honolulu.

Even at Disneyland, I’ve picked up free bandages for my blistered feet at a first aid station in the park.

Most hotels and vacation rentals provide irons, hairdryers and towels, so definitely don’t pack those bulky items. Some also offer items like robes and umbrellas.

You net a great souvenir

On a trip to Thailand, I intentionally under-packed. Buying a sundress, shirts, sandals and floppy hat from vendors who lined the beach was all part of the experience. Plus, they’re functional souvenirs that I truly love.

How to maximize your rewards

You want a travel credit card that prioritizes what’s important to you. Here are some of the best travel credit cards of 2024 :

Flexibility, point transfers and a large bonus: Chase Sapphire Preferred® Card

No annual fee: Wells Fargo Autograph℠ Card

Flat-rate travel rewards: Capital One Venture Rewards Credit Card

Bonus travel rewards and high-end perks: Chase Sapphire Reserve®

Luxury perks: The Platinum Card® from American Express

Business travelers: Ink Business Preferred® Credit Card

On a similar note...

Funds “Travel” Regulations: Questions & Answers

The following is revised guidance to financial institutions on the transmittal of funds "Travel" rule. This guidance updates the document “Funds ‘Travel’ Regulations: Questions & Answers” issued in 1997. It includes a parenthetical at the end of each answer indicating the date the answer was issued.

1. Are all transmittals of funds subject to this rule?

No. Only transmittals of funds equal to or greater than $3,000 (or its foreign equivalent) are subject to this rule, regardless of whether or not currency is involved. In addition, transmittals of funds governed by the Electronic Funds Transfer Act (Reg E) or made through ATM or point-of-sale systems are not subject to this rule. (January 1997)

2. What are the "Travel" rule's requirements?

All transmittor's financial institutions must include and send the following in the transmittal order:

- the name of the transmittor

- the account number of the transmittor, if used

- the address of the transmittor

- the identity of the transmittor's financial institution

- the amount of the transmittal order

- the execution date of the transmittal order

- the identity of the recipient's financial institution

and, if received:

- the name of the recipient

- the address of the recipient

- the account number of the recipient, and

- any other specific identifier of the recipient.

An intermediary financial institution must pass on all of the above listed information, as specified in the travel rule, it receives from a transmittor's financial institution or the preceding intermediary financial institution (exceptions are noted below, in FAQ #3), but has no general duty to retrieve information not provided by the transmittor's financial institution or the preceding intermediary financial institution.

An intermediary financial institution may receive supplementary information about a payment beyond the information the travel rule requires to be sent to the next financial institution in the payment chain. For example, a payment order may contain additional information about the payment or the parties to the transaction. Due to differences in format and detail included in different systems, such as Fedwire, CHIPS, SWIFT and proprietary message formats, this additional information may not be readily transferable to the format used to send a subsequent payment order. In that event, the sending intermediary institution would be in compliance with the travel rule as long as all of the information specified in the travel rule was included in the subsequent payment order. The information does not have to be structured in the same manner or appear in the same format so long as all of the information required by the travel rule is included. For example, if certain information specified in the travel rule was present in two or more fields in the payment order received, that information need only be included once in the payment order sent to satisfy the requirements of the travel rule.

Intermediary financial institutions in receipt of additional information not required by the travel rule should note that, while compliance with the travel rule is accomplished by inclusion of the information identified in the rule, other monitoring and reporting requirements may apply to additional information and nothing in this FAQ relieves a financial institution of any of its duties with regard to other requirements. In addition, as a matter of risk management, an intermediary financial institution may choose to provide a receiving financial institution supplemental information about a payment and the parties involved. Currently, limited interoperability between systems may prevent a bank from choosing to include certain supplementary information in a payment order. These limitations, however, may be temporary as systems develop.

Moreover, if any lawful order is received at, or if a request from another financial institution is made to a recipient's financial institution, all financial institutions must go back to the transmittor's financial institution, or any other preceding financial institution, if the transmittor's financial institution is unknown, and retrieve information required by the travel rule not included in the transmittal of funds due to system limitations. (Updated November 2010)

3. Are there any exceptions to these requirements?

Yes. If the transmittor and the recipient are the same person, and the transmittor's financial institution and the recipient's financial institution are the same domestic bank or domestic securities broker, the transaction is excepted from the requirement contained in these new rules.

In addition, if both the transmittor and the recipient, that is, as defined, the beneficial recipient, are any of the following, then the transmittal of funds is not subject to these rules:

- Domestic bank;

- Wholly owned domestic subsidiary of a domestic bank;

- Domestic broker or dealer in securities;

- Wholly owned domestic subsidiary of a domestic broker or dealer in securities;

- Domestic futures commission merchant or an introducing broker in commodities;

- Wholly owned domestic subsidiary of a domestic futures commission merchant or an introducing broker in commodities;

- The United States;

- Federal agency or instrumentality;

- State or local government; State or local agency or instrumentality; or

- Domestic mutual fund. (Updated November 2010)

4. Does this rule require any reporting to the government of any information?

No. However, if a transmittal of funds seems to the financial institution to be suspicious, then a Suspicious Activity Report is required, if the financial institution is subject to the Bank Secrecy Act's suspicious activity reporting requirement. (January 1997)

5. How long does a financial institution have to keep records required by these new rules?

Five (5) years. (January 1997)

6. What is the benefit of this rule to the public?

Law enforcement authorities have identified instances to the Treasury in which records maintained by financial institutions were incomplete or insufficient and thereby hampered criminal investigations. In addition, in certain criminal investigations, financial institutions were unable, on a timely basis, to provide law enforcement authorities with useful financial records of transmittals of funds. This rule was created to ensure that in criminal investigations, as well as tax or regulatory proceedings, sufficient information would be available to quickly enable authorities to determine the source of the transmittal of funds and its recipient. Finally, it is anticipated that this rule will more easily permit law enforcement authorities to determine the parties to a transaction. (January 1997)

7. What is a financial institution for the purposes of this rule?

The term "financial institution" includes: banks; securities brokers or dealers; casinos subject to the Bank Secrecy Act; money transmitters, check cashers, currency exchangers, and money order issuers and sellers subject to the Bank Secrecy Act; futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities; and mutual funds. Please see 31 CFR 103.11 for more information. (November 2010)

8. Does this rule treat banks and non-bank financial institutions differently?

No. Banks and non-bank financial institutions are treated identically under the Travel rule. (January 1997)

9. What are some of the implications of the Travel rule for financial institutions subject to this rule?

The most important implication is that financial institutions must be aware that if a transmittal of funds involves both bank and non-bank financial institutions, each financial institution must carefully analyze and understand all of the definitions that apply to its role in the transmittal of funds. This is important because the rule's requirements on financial institutions differ, depending on what role a financial institution plays in a transmittal of funds.

For example, in a situation in which the customer of a securities broker initiates a transmittal of funds that is sent through a bank, that bank is an intermediary financial institution for the purposes of the Travel rule.

The next important implication is that financial institutions must carefully understand the role of the succeeding financial institution in the chain of each transmittal of funds, particularly where a transmittal of funds moves from a bank to a non-bank, or vice versa. This is important because the Travel rule's requirement to pass information to the next financial institution in the chain implicitly requires financial institutions that carry out transmittals of funds to coordinate the transfer of information required by this new rule.

Finally, as the range of services offered by financial institutions expands, financial institutions must recognize that a single transmittal may involve two or more funds transfer systems. In such cases, it is important that financial institutions understand their roles in such a complex transmittal of funds, because their duties under this rule arise from their role(s) in the transmittal of funds. (January 1997)

10. What is the relationship between the terms used in this rule and those used within Article 4A of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC)?

This rule uses terms that are intended to parallel those used in UCC Article 4A, but that are applicable to all financial institutions, as defined within the Bank Secrecy Act's implementing regulations.

(January 1997)

11. Do the terms created in this regulation apply to transmittals of funds to or from anywhere in the world?

Yes. However, the requirements of the Bank Secrecy Act apply only to activities of financial institutions within the United States. Thus, for example, part, but not all, of an international transmittal of funds can be subject to the Travel rule. (January 1997)

12. Is this rule limited to wire transfers?

No. The term transmittal of funds includes other transactions and transfers in addition to wire transfers or electronic transfers. (January 1997)

13. What are examples of transmittals of funds that are not wire transfers?

Financial institutions sometimes carry out transmittals of funds using correspondent accounts or journal entry transfers such as "due from" and "due to" accounts. In such cases, covered transmittals of funds have occurred even though no wire transfer has occurred.

In addition, a check can be the transmittal order within a transmittal of funds. This limited case occurs when Customer 1 goes into Financial Institution A and orders a transmittal of funds be sent to Customer 2 at Financial Institution B. Financial Institution A, perhaps because it is a small financial institution or because the transaction involves a function (such as a trust) that is segregated from the rest of the financial institution, sends a check, payable to Financial Institution B, directly to Financial Institution B, and does not send the check directly to Customer 1 or to Customer 2. This check must be Financial Institution A's own check (however, it need not be drawn on Financial Institution A), and not the check of the customer. This check contains accompanying instructions to have Financial Institution B subsequently credit Customer 2's account. In such a case, the check and its instructions are the transmittal order effecting a transmittal of funds. (January 1997)

14. How should aggregated transmittals of funds be treated?

This is a situation where a financial institution aggregates many separate requests for transmittals of funds into one combined transmittal of funds.

Whenever a financial institution aggregates separate transmittors from separate transmittals of funds, the transmittor's financial institution itself becomes the transmittor, for the purpose of the Travel rule. Conversely, any time a financial institution combines separate recipients from separate transmittals of funds, the recipient's financial institution itself becomes the recipient, for the purpose of the Travel rule.

For example, if a money transmitter has five (5) customers who wish to have funds disbursed to five separate recipients at a separate money transmitter, and the money transmitter uses a bank to carry out the movement of funds, the bank might aggregate the five (5) separate customers. In such an instance and for the purposes of the Travel rule, the bank may list as transmittor the transmittors’ money transmitter, and as recipient the recipients' money transmitter. However, the transmittors' money transmitter itself is independently obligated to make travel the required information to the recipients' money transmitter. Thus, the information is still required to travel in an aggregated transmittal of funds, although not necessarily in the same manner or by the same parties as in a non-aggregated transmittal of funds. (January 1997)

15. How should joint party transmittals of funds be treated?

For example, Ms. A and Ms. B, sisters with different names and addresses, jointly act as the transmittor or as the recipient. In such cases, it may be impossible to transfer all the information required under the Travel rule. In this instance, the Treasury suggests the following:

When a transmittal of funds is initiated by more than one transmittor, or sent to more than one recipient, the transmittor's financial institution may select one transmittor, or one recipient, as the person whose information must be passed under the “Travel” rule. In all cases involving a transmittal of funds from a joint account, the account holder that ordered the transmittal of funds should be identified as the transmittor on the transmittal order. Please note that for the Joint Rule [31 CFR 103.33(e) and (f)], records must still be kept on all parties. (January 1997)

16. How should a financial institution treat a customer who uses a code name or a pseudonym, or a customer who has requested that the financial institution hold his/her mail?

For purposes of compliance with the Travel rule, the use of a code name or pseudonym is prohibited. In all such cases, the financial institution must use the customer's true name, and the customer's address. Customers may use abbreviated names, names reflecting different accounts of a corporation, as well as trade and assumed names, or names of unincorporated divisions or departments of businesses.

There may be legitimate reasons for having the financial institution's address serve as the transmittor's mailing address, such as where a customer has requested that the financial institution hold his/her mail. Consequently, so long as the financial institution maintains on file the transmittor's true address and such true address is retrievable upon request by law enforcement, the financial institution may comply with Section 103.33(g) by forwarding with the transmittal order the customer’s mailing address that is maintained in its automated Customer Information File (CIF) (even if that address happens to be the bank's own mailing address). (Updated November 2010)

17. To whom can a financial institution go should it have further questions?

Any financial institution may contact its primary Bank Secrecy Act examination authority, or the Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network can be contacted regarding questions on the Bank Secrecy Act rules at (800) 949-2732. (Updated November 2010)

The FinCEN Travel Rule

- February 25, 2021

- AML Compliance , Banks , Blog , Casino and Gaming , FinTechs , MSBs

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are intended to provide a general understanding of the subject matter. However, this article is not intended to provide legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as such.

The FinCEN “Travel Rule” has many requirements and nuances that can challenge and confuse new and seasoned AML compliance professionals alike. From the basics of what types of transactions fall under the Rule, to mandatory versus optional data requirements, to its many exemptions – as well as the nuances addressed by subsequent FinCEN guidance not contained in the Rule itself – compliance professionals need to understand the details of this longstanding Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) regulation.

This article begins with a review of the fundamentals of the FinCEN Travel Rule , and why compliance is so important to anti-money laundering efforts. Learn about the nuances of complying with the Travel Rule, including a discussion of pending changes to the Travel Rule in an October 2020 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; Fedwire versus Travel Rule requirements; aggregated funds transfers; Originator name issues; and transfers by non-customers.

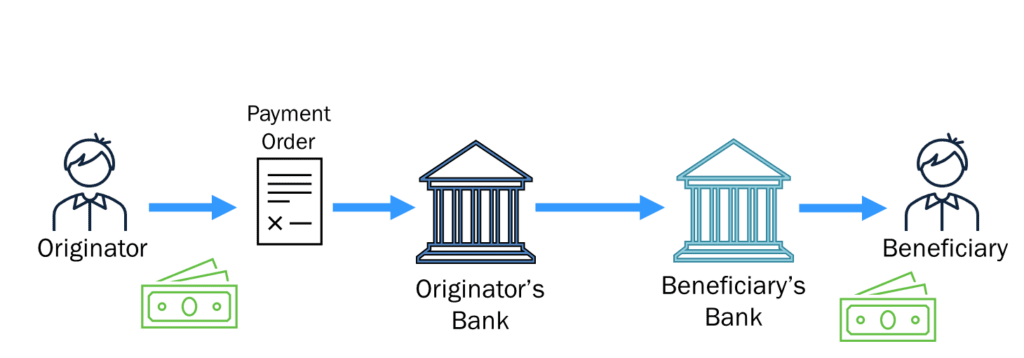

What is the FinCEN Travel Rule?

In January 1995, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN jointly issued a Rule for banks and other nonbank financial institutions, relating to information required to be included in funds transfers. The Rule is comprised of two parts – the Recordkeeping Rule, and what’s come to be known as the Travel Rule. The Travel Rule was promoted by FinCEN, in keeping with their mandate to enforce the Bank Secrecy Act .

The Recordkeeping Rule and the Travel Rule are complementary. The Recordkeeping Rule requires financial institutions to collect and retain the information that in turn, per the Travel Rule, must be included with a funds transfer and passed along – or “travel” – to each successive bank in the funds transfer chain. The Recordkeeping Rule does however serve other purposes besides ensuring that information is available to include with funds transfers.

The terms “transfer” and “transmittal” are used throughout this regulation. The distinction between these two terms is simple: a bank performs transfers, and a non-bank financial institution performs transmittals. The term “transfer” will primarily be used from this point on to refer to both types of transactions.

The Underlying Objective

Fund transfers have been the tool of choice for money laundering, fraud, and much more, for decades. As FinCEN’s mission is to implement, administer, and enforce compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act, it has the authority to require financial institutions to keep records that, according to FinCEN, have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or even in intelligence or counterintelligence matters when terrorism is involved.

Ultimately, the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is primarily designed to help law enforcement to detect, investigate and prosecute money laundering and financial crimes, by preserving the information trail about who’s sending and receiving money through funds transfer systems. In other words, it helps them follow the money.

Transactions Subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule

The Recordkeeping and Travel Rule states that it applies to funds transfers. The definition of a funds transfer is very important, as highlighted later in the discussion of the most recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

The Rule defines a funds transfer as a series of transactions, beginning with the Originator’s payment order, made for the purpose of making a payment of money to the Beneficiary of that payment order.

Below is a basic illustration of a funds transfer. An Originator creates a Payment Order to pay money to a specific Beneficiary. The Originator delivers the Payment Order to his bank, which then passes on the Payment Order details to the bank holding the Beneficiary’s account. The funds transfer is complete when the Beneficiary’s Bank accepts the Payment Order on behalf of the Beneficiary.

In today’s world, funds transfers are electronic, and a wire transfer is the most common form of electronic funds transfer. At its essence, a wire transfer is simply a message from one bank to another, passed through an electronic system, such as Fedwire, SWIFT , or CHIPS.

Electronic Funds Transfers That are Excluded

Besides wire transfers, there are many types of electronic funds transfers, or EFTs in use today. Although all are in essence funds transfers, these types of transactions are specifically excluded from the definition of a funds transfer or transmittal in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Instead, these types of electronic funds transfers are defined in, and governed by, the Electronic Funds Transfer Act, otherwise known as Regulation E. [i] Currently, these are:

- ACH (automated clearing house) transactions

- ATM (automated teller machine) transactions

- Point of Sale (POS) transactions

- Direct deposits or withdrawals

- Telephone banking transfers

Terminology Review

The terminology used in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is in many cases unique. The more commonly-used terms when referring to wire transfers and other electronic funds transfers come from the Uniform Commercial Code’s Article 4A, which governs funds transfers. [ii]

Throughout this article, UCC 4A terminology will be used as it is more commonly understood:

* The spelling shown here is per the regulation; it is not the correct spelling of this word according to widely-accepted sources.

The term Sender per UCC 4A refers to the person who is delivering the Payment Order to the Receiving Bank. This person would typically be the Originator, but could potentially be a third party, as discussed further below.

Funds Transfer Data Requirements

The Rule divides the data requirements on a funds transfer into two groups: (1) data that is mandatory, and (2) data that, if the originator provides it , must be included.

First, the data that must be included on the funds transfer by the Originator’s Bank is:

- The Originator’s name

- The Originator’s address

- The Originator’s account number (if there is one)

- The identity of the Beneficiary’s Bank

- The payment amount

- The payment execution date

Typically, a bank will automatically populate the Originator’s name and address information on a wire transfer directly from the customer record. This is because it is very important that the Originator’s name reflects the actual party initiating the Payment Order. (This topic is explored further in the Deep Dives section below.)

The second group of data elements is optional – meaning, if the Originator provides any of this information, it must be included on the funds transfer record. This information includes:

- The Recipient’s (or Beneficiary’s) name

- The Beneficiary’s address

- The Beneficiary’s account number or other identifiers

- Any other message or payment instructions – what typically are entered in the freeform text fields on a wire transfer, such as the Originator to Beneficiary Information or OBI field on a Fedwire.

Even though this information is not mandatory per FinCEN’s Travel Rule requirements, nothing precludes a bank from mandating customers to supply it. From an operational perspective, at least the Beneficiary’s account number should be required information to minimize the risk that the transfer will be rejected and returned by the Receiving Bank as unpostable.

As well as being highly valuable to law enforcement, Beneficiary information is critical to a bank’s fraud detection , suspicious activity monitoring and sanctions compliance efforts. Without this information, detecting an unusual or suspicious wire transfer recipient, establishing a pattern of transaction activity to a particular recipient, or identifying a customer transaction with an OFAC-sanctioned party is impossible.

Exemptions from the Travel Rule

In addition to the types of EFTs that are not subject to the Rule (as they fall under the jurisdiction of Regulation E) there are several categories, or classes, of funds transfers that are exempt from FinCEN’s Travel Rule’s requirements. Specifically:

- A funds transfer that is less than $3,000.

- A funds transfer where the sender and the recipient are the same person . For example, if an individual is wiring money from her account at Bank A to her account at Bank B, Bank A does not have to obtain and retain the Travel Rule mandatory information for this transfer.

- A funds transfer made between two account holders at the same institution. Commonly known as a book transfer, this transaction is not processed through the Federal Reserve, but is simply a journal entry on the financial institution’s books.

- A bank, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A commodities/futures broker, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- The U.S. government; a state or local government

- A securities broker/dealer, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A mutual fund

- A federal, state or local government agency or instrumentality

Nothing prevents a financial institution from ignoring these exemptions; the institution is free to follow the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule requirements with every funds transfer. Such a practice benefits all the financial institutions involved in the transaction, as well as law enforcement.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Enforcement

FinCEN enforcement actions over the years have never solely targeted violations of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. This is likely because as a matter of operational efficiency, financial institutions typically populate the basic mandatory information on all outgoing funds transfers and maintain records of such.

However, it is important not to overlook the other key element of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule: records retrievability.

A financial institution may be approached by federal, state, or local law enforcement, its regulator, another regulatory agency, or by subpoena, to provide specific funds transfer records.

If the institution is the Originator’s Bank, the mandatory funds transfer information to be collected and retained (Originator name & address, etc.) must be retrievable upon request, based on the Originator’s name . If the Originator is the institution’s established customer, transaction retrieval by the Originator’s account number may also be requested. A Beneficiary’s Bank must be able to retrieve funds transfer records by the Beneficiary’s name, and if an established customer, also by account number.

The FinCEN Travel Rule requires all funds transfer records to be retained for a minimum of five years from the date of the transaction.

Once funds transfer records are requested, the Rule states they must be supplied within a reasonable period – which may likely be negotiated between the financial institution and the requestor.

The 120-Hour Rule

However, financial institutions should be aware of a lesser-known clause within Section 314 of the USA PATRIOT Act that could impact records retrieval. Commonly known as the 120 Hour Rule , it states that any information, on any account that is opened, maintained, or managed in the U.S. requested by a federal banking agency, must be provided by the financial institution within 120 hours (5 days) after receiving the request. Funds transfer records would likely fall within the scope of this Rule.

Anecdotally, regulators have not imposed the 120 Hour Rule often. Financial institutions should nevertheless be prepared to respond to regulatory or law enforcement requests as quickly and efficiently as possible. IRS and civil case subpoenas requesting funds transfer records also typically have a short response window.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Guidance: A Deep Dive

The following sections explore deeper topics relating to Recordkeeping and Travel Rule guidance, including:

- The October 2020 Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking impacting the Rule

- Fedwire versus the Travel Rule

- Originator name issues

- Aggregated funds transfers

- Funds transfers for non-customers

Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

On October 23, 2020, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN issued a Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to amend the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule regulations. Written comments on the Proposed Rule were due by the end of November 2020. The next step is a publication of the Final Rule, but FinCEN has not set a date for this.

According to the website Regulations.gov , 2,882 comments were submitted for the NPRM. Commenters ranged from major banking groups such as the American Bankers Association to private individuals. The comments were overwhelmingly negative.

The NPRM proposes two major changes, discussed below.

Reducing the Minimum Dollar Threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Compliance on Cross-Border Funds Transfers

Part 1 of the NPRM proposes reducing the $3,000 threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule compliance to $250 for cross-border transactions. The threshold for domestic transactions would remain at $3,000.

While this change may not have a major impact on financial institutions that ignore the dollar threshold exemption, it would significantly impact those institutions that follow it. There are some interesting nuances in this proposed change regarding what is meant by “cross border.”

Initially, a “cross-border” transaction is defined as one that, “begins or ends outside of the United States.” The United States includes the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Indian lands (as that term is defined in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act), and the Territories and Insular Possessions of the United States. [iii]

A funds transfer would be considered to “begin or end outside the United States” if the financial institution knows, or has reason to know, that the Originator, the Originator’s financial institution, the Recipient/Beneficiary, or the Recipient/Beneficiary’s financial institution is located in, is ordinarily resident in, or is organized under the laws of a jurisdiction other than the United States. Furthermore, a financial institution would have “reason to know” that a transaction begins or ends outside the United States only to the extent such information could be determined based on the information it receives in the payment order or otherwise collects from the Originator.

The driving factor behind this regulatory change is the benefit to law enforcement and national security. FinCEN’s analysis of SAR filings , as well as comments collected by the Department of Justice from agents and prosecutors at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Secret Service, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, all supported lowering (or eliminating altogether) the reporting threshold, in order to disrupt illegal activity and increase its cost to the perpetrators.

According to FinCEN and these other law enforcement agencies, cross-border funds transfers, and especially lower dollar transfers in the $200 to $600 dollar range, are being used extensively in terrorist financing and narcotics trafficking to avoid reporting and detection.

For those institutions that abide by the minimum reporting threshold, the new lower cross-border threshold presents operational and programmatic challenges. The distinction between a cross-border and a domestic transaction is not always clear. For example, if a financial institution has no direct foreign correspondent banking relationships, its cross-border funds transfers must flow through a U.S. intermediary institution, and therefore the Federal Reserve. Automated systems may interpret such transactions as domestic because the first receiving institution will always be U.S.-based.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Applies to Virtual Currency

The second element of the NPRM would make funds transfers involving convertible virtual currency (CVC) and other digital assets, to be subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. CVC, more commonly known as cryptocurrency or cyber-currency, is a medium of exchange with an equivalent value in currency or acts as a substitute for currency, but at present does not fall under the regulatory definition of “money” (also known as legal tender).

The Proposed Rule now defines CVC as money. This is significant because transfers of CVC now legally fall within the meaning of “a transfer of money” to which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule applies.

The “why” behind this aspect of the Proposed Rule is the exponential growth in CVC use for money laundering, terrorist financing, organized crime, weapons proliferation, and sanctions evasion. CVC’s anonymity makes it particularly attractive for financial crime. Bad actors can convert illegal proceeds into virtual currency and then transmit it to any destination anonymously within seconds, where it is redeemed for cash again or converted to another form. This makes CVC a perfect mechanism for the layering phase of money laundering.

For more information, check out our blog on the crypto travel rule .

NPRM Background and the “FATF Travel Rule”

Events leading up to the NPRM provide an interesting background, especially as they are intertwined with global anti-money laundering efforts – specifically those of the Financial Actions Task Force (FATF) and what has come to be known as the “FATF Travel Rule.”

As virtual currency’s popularity began to grow exponentially, regulators in the United States and globally were caught off-guard. It was not well understood, and there were no real protocols in place to govern it. In March 2013 , FinCEN released initial guidance clarifying that virtual currency exchangers and administrators must register as money service businesses, pursuant to federal law. [iv]

In October 2018 , FATF published guidance that clearly defined just what are virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (VASPs). [v] FATF followed this up in February 2019 with a far-reaching Interpretive Note to Recommendation 15 (New Technologies), in a Public Statement titled “Mitigating Risks from Virtual Assets.” [vi]

This publication included two key proposals that generated backlash from the cryptocurrency sector:

For one, it proposed that VASPs should, at a minimum, be required to be licensed or registered in the jurisdiction(s) where they are created. As well, VASPs should be subject to effective systems for monitoring compliance with a country’s AML/CFT requirements, and be supervised by a competent authority – not a self-regulatory body.

Second, it introduced what’s come to be known as the FATF Travel Rule for funds transferred over $1,000 – specifically referencing virtual asset transfers. These requirements match up point-for-point with the United States Recordkeeping and Travel Rule in terms of required funds transfer data to be obtained, retained and passed on.

In May 2019 , FinCEN published lengthy and complex guidance [vii] effectively stating that CVC-based transfers processed by nonbank financial institutions that meet the definition of a money service business are subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), and thereby the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Furthermore, it clarified that a transfer of virtual currency involves a sender making a “transmittal order.”

One month later in June 2019 , the FATF formally adopted the proposals from their 2018 guidance by incorporating them into the FATF 40 Recommendations – specifically, Recommendation 16, Wire Transfers.

In October 2020, the Federal Reserve Board and FinCEN issued their Joint NPRM, which would codify their May 2019 guidance as well.

Fedwire vs. the FinCEN Travel Rule

With respect to the implementation and enforcement of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule, there is an interesting disconnect between the two key divisions of the U.S. Treasury Department. FinCEN is tasked with administering and enforcing the BSA, of which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is a part. The Federal Reserve Banks, also part of the US Treasury Department, own and operate Fedwire , the country’s primary funds transfer service. Yet the Fedwire system does no validation whatsoever that funds transfers processed through it include the basic, mandatory information required by the Travel Rule. The only data elements required to process a Fedwire transfer are the sending and receiving banks’ Fed routing numbers, the transaction amount, and its effective date. [viii]

One might conclude that law enforcement could have much more information on funds transfers at its disposal if the federal government’s actual funds transfer system made that information required. Today, should an Originator’s Bank fail to include the Travel Rule’s mandatory information (Originator’s name and address, etc.) on a funds transfer, the Receiving Bank is under no obligation to return the transfer and request the mandatory information. Instead, the burden is solely on the Originator’s Bank to comply, and any subsequent Receiving Banks’ responsibility is simply to retain (and pass on, if necessary) the information received.

Aggregated Funds Transfers

A financial institution may aggregate, or combine, multiple individual funds transfer requests into a single, aggregated funds transfer/transmittal.

For purposes of the FinCEN Travel Rule, whenever a financial institution aggregates multiple parties’ transfer requests into one single transfer, the institution itself becomes the Originator. Similarly, if there are multiple Beneficiaries in this aggregated transfer, but all with accounts at the same Receiving institution, then that institution becomes the Beneficiary on the aggregated funds transfer.

Aggregated funds transfers are common with money service businesses , as illustrated here: